Abstract

Per diems are used to pay work-related expenses and motivate employees, yet they also can distort incentives and may be abused. This study was designed to explore perceptions of per diems among 41 high-, mid- and low-level government officers and non-governmental organization (NGO) officials in Malawi and Uganda. Interviews explored attitudes about per diems, benefits and problems for organizations and individuals, and risks and patterns of abuse. The study found that per diems provide benefits such as encouraging training, increasing staff motivation and supplementing salary. Despite these advantages, respondents voiced many discontents about per diems, stating that they create conflict, contribute to a negative organizational culture where people expect to be paid for all activities, and lead to negative changes in work time allocation. Work practices are also manipulated in order to maximize financial gain by slowing work, scheduling unnecessary trainings, or exaggerating time needed for tasks. Officials may appropriate per diems meant for others or engage in various forms of fraud for personal financial gain. Abuse seemed more common in the government sector due to low pay and weaker controls. A striking finding was the distrust that lower-level workers felt toward their superiors: allowances were perceived to provide unfair financial advantages to already better-off and well-connected staff. To curb abuse of per diems, initiatives must reduce pressures and incentives to abuse, while controlling discretion and increasing transparency in policy implementation. Donors can play a role in reform by supporting development of policy analysis tools, design of control mechanisms and evaluation of reform strategies.

Keywords: Per diems, allowances, health policy, corruption, fraud

Introduction

The term per diem is Latin for ‘by the day’, and refers to prospectively determined daily allowance paid by an employer, development agency, or client to cover approved employee expenditures. A per diem may be paid for activities such as travel to supervise projects or work away from the duty post, attending meetings, or participating in training.

Developing countries spend a lot on per diems and other types of employment-related allowances. The Government of Tanzania spent US$390 million on allowances in 2009, equivalent to 59% of annual spending on salaries and wages or the annual salary of 109 000 teachers (Policy Forum 2009). A study conducted in two districts in Burkina Faso found that per diem income actually exceeded health worker salaries (Ridde 2010). Examining aid effectiveness in a Tanzanian natural resource programme, researchers estimated that 50–70% of the US$60 million project was spent on capacity building of government staff and local populations in the form of training workshops, per diems and travel expenses (Jansen 2009).

Policy makers have justified spending on per diems as necessary to reimburse out-of-pocket expenses for meals, lodging and incidentals, as well as to encourage professional development activities and motivate employees to travel or work under difficult conditions (e.g. in settings where travel is slow and uncomfortable, it is not possible to return home at night, and infrastructure and choices for working, sleeping, eating and entertainment are limited). But increasingly, per diems are a strategy for supplementing salaries of health workers who are ill-paid or whose pay cheques are months behind (Roenen et al. 1997; Chêne 2009).

With so much money at stake, it is not surprising that per diems create problems. Although there is not a lot of published literature on the problem of per diems, US researchers working on public health projects in developing countries expressed concern about the ways in which per diem policies were affecting work practices, including delays caused by people attending training programmes unrelated to work targets, and falsification of records by employees in order to gain more per diems (Vian 2009). An editorial appearing in the journal Tropical Medicine & International Health urged that development professionals find an ‘equitable treatment for this long-neglected disease [of] perdiemitis’ (Ridde 2010).

This study was designed to fill in gaps in our knowledge about the problems created by per diems and possible solutions. While Western public health professionals have raised concerns, it is not clear whether people in developing countries also perceive negative effects of per diems or how people at different levels of the health system are affected. Drawing on the perceptions of people from inside the system—who gains, who loses, who abuses and why—we can better understand the drivers of current practices and identify levers for reform.

Methods

The study was designed to answer the following research questions through semi-structured interviews in two countries:

What are the advantages and disadvantages of per diems from the perspective of people working in the public and non-governmental organization (NGO) sector?

How do people abuse policies related to per diems and allowances?

What kinds of solutions might improve policies and limit opportunities for abuse?

Malawi and Uganda offered the opportunity to study per diems in slightly different African contexts: for example, Malawi is poorer (per capita income of US$800 vs US$1300 in Uganda), with lower health spending (4.8% of gross domestic product (GDP) vs 8.2% in Uganda) and worse health statistics (81 infant deaths per 1000 live births in Malawi vs 62 in Uganda) (CIA 2011). We also had prior relationships with local researchers in each of these countries which made the study more efficient. The research protocol was reviewed by the Boston University Medical Center Institutional Review Board and considered exempt from regulations for protection of human subjects.

The field researchers each had prior training in qualitative interviewing methods and over 10 years’ experience conducting social science research within the public sector and with NGOs. One has a PhD in medical anthropology; both had worked previously on multiple international studies and were living in the areas where the interviews were conducted.

The protocol for recruiting participants was as follows. First, each field researcher identified an initial informant. Then, using snowball sampling, one informant led to another informant who met the criterion of having worked at least 1 year in their position. Informants were stratified to represent high-, mid- and low-level positions in government and NGOs. Each researcher reported having had prior encounters with 5 (25%) of their informants. Participation was voluntary and researchers obtained informed consent. Informants did not receive any payment to participate in the study.

Data collection took place from October 2010 through January 2011. Following a grounded theory approach, we sought a sample size of about 20 informants in each country (Creswell 2007). Researchers found that categories of information became saturated at this point. Informants were asked to identify places where they could talk freely. Often people were interviewed in their office with the door closed, but interviews were also held in cafes, hotels, homes and health facilities. They took 30 minutes on average (range: 19–60 minutes) and were conducted in English. Where permission was given, interviews were recorded and transcribed by the research team members. Researchers in Boston reviewed selected transcripts and compared them with tape recordings to control for accuracy of transcription.

In conducting interviews, participants were first asked “What kinds of allowances are given to employees of your level in this organization? Can you tell me about the rules for that kind of allowance?” The study team and interview participants sometimes used the more general term ‘allowance’ when referring to prospectively determined daily allowances or ‘per diems’, the focus of this article. In the remainder of this manuscript, we use these terms interchangeably.

The Boston research team members analysed the first 4–5 transcripts from each country and provided feedback to local researchers about themes and areas for probing. While we did not use a constant comparative method of data analysis which would require analysis of each interview to inform the next, the phased approach to data collection helped inform the questioning in subsequent interviews. Transcripts were imported into NVivo 9® software for analysis of themes.

Results

Informants

In Malawi, government informants came from the Ministry of Health in Lilongwe, Mchinji and Blantyre districts, a nursing college and health facilities. There were also three international and two local NGO informants (Table 1). In Uganda, government informants came from line ministries including health, public commissions and local government/districts. NGOs included a multilateral agency, a global consortium and local NGOs.

Table 1.

Levels and types of positions held by informants

| Level | Type of position | Malawi |

Uganda |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Government | NGO | Government | NGO | ||

| High/Senior | Commissioner, Chairman, Service Director, Professional Officer, District Health/Medical Officer. Travel internationally for work. | 5 | 2 | 4 | 1 |

| Mid | Senior Research Officer, Health Center or Hospital Nurse, Nurse Lecturer, Senior Medical or Clerical Officer, Project Officer | 5 | 3 | 6 | 3 |

| Low/Junior | Driver, Health Surveillance Assistant, Personal Secretary | 5 | 0 | 6 | 1 |

| Total | 15 | 5 | 16 | 5 | |

Note: Selection of informants was stratified by level for Government employees, but not for non-governmental organization (NGO) informants.

Types and purpose of allowances

Although participants described many types of allowances (Table 2), in this analysis we are mainly interested in perceptions about per diems. Government and NGO employees in Malawi and Uganda are entitled to a per diem if they are called to work outside their duty station. Per diems are smaller if they do not spend the night or if the employer pre-pays accommodation.

Table 2.

Types and purpose of allowances

| Name | Description/purpose | Country |

|---|---|---|

| Per diem, night, or subsistence allowance | Amount paid for travel outside one’s duty station which involves an overnight stay. Hotel may be pre-paid in which case per diem rate is reduced. | Malawi, Uganda |

| Lunch allowance | Paid for work during lunch time, whether within or outside duty station. Usually approved in advance. | Malawi, Uganda |

| Safari Day Allowance (SDA) | When an officer travels on duty for a period of 6 hours or more and returns to duty station the same day. | Uganda |

| Honoraria | Paid to a civil servant assigned work of great importance to government and involving added responsibilities. | Uganda |

| Locum or overtime | Paid to compensate clinical staff working extra hours, often to cover for shortages of staff. | Malawi (locum), Uganda (overtime) |

| Transport allowance | Money paid to officers to cover expense of going from home to office. In addition, people may claim for actual expenses incurred (e.g. fuel, bus) for work-related travel. | Uganda |

| Training or facilitation | Training allowances include professional fee for presenting paper, part-time lecturer; books. | Malawi, Uganda |

| Other allowances | Hardship; housing; relocation/baggage; air time; responding to outbreaks; medical; security; funeral. | Malawi, Uganda |

Note: ‘Names’ are words used by informants in Malawi or Uganda to describe the allowance.

Perceptions of equity and fairness

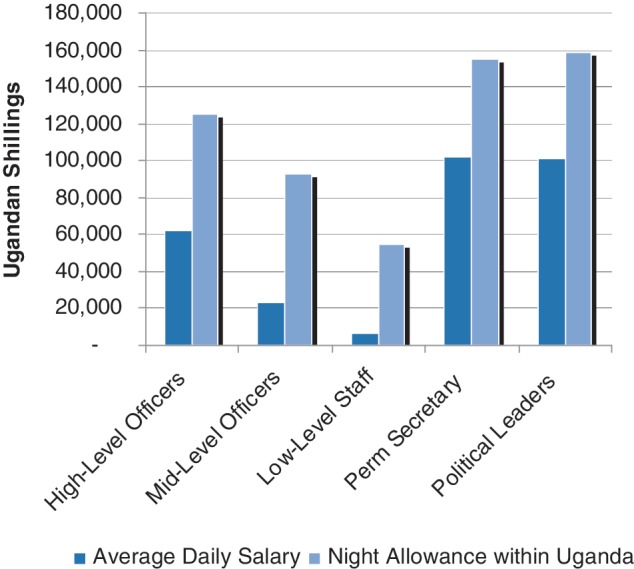

In many cases, higher-level staff received higher rates of per diems. Rates also varied by location and by sponsor. We were able to obtain data which allowed us to compare the per diem rates to daily government salary rates in Uganda (Figure 1). The data highlight the fact that per diems are much higher than daily wage rates, and can represent a significant source of income. (Exchange rates at the time of study were approximately 2000 Uganda Shillings (UGX) and 153 Malawi Kwacha (MWK) per $1.00 USD.) In Uganda, low-level workers such as drivers or nursing assistants are eligible to receive a nightly per diem of 55 000 UGX, or close to 9 times the average daily wage of 6261 UGX. For medical officers the difference was less but still important: high-level workers can earn a per diem of 125 000 UGX, about twice their average daily wage of 61 847 UGX.

Figure 1.

Average daily salary vs per diem (night allowance) within Uganda, by type of government employee. Note: Salary data from FY2010/2011. Most recent revised per diem rates as released in 2008 government circular. Categories of high-, mid- and low-level staff were created by the authors. High-level officers include Principal and Senior Medical Officers; mid-level officers include nurses, laboratory technicians, and teachers; low-level staff include nurse assistants and drivers.

A number of government informants at all levels felt that rates which varied by cadre of staff were fair, as shown in these quotes:

“I think it is a fair system that whoever is senior is supposed to get more, just like salaries. If you are senior, you get more salary than one who is junior.” (high-level officer, Malawi)

“It would be undermining if we got the same allowance as the boss … You cannot sit or sleep in the same chair or bed with your boss.” (low-level officer, Uganda)

However, a few informants felt that differences in rates were not fair, since per diems are meant to pay for travel-related expenses which did not differ much by cadre.

“Since allowances are meant to make you comfortable, why should it be different for a driver or a Chief Executive officer? You are all traveling in the same car and going to the same area.” (mid-level officer, Uganda)

NGO informants reported that they received the same rates irrespective of staff level.

Advantages

Respondents noted important advantages of per diems and allowances to organizations and employees (Box 1).

KEY MESSAGES.

Per diems help to motivate workers, but also have perverse effects and breed discontent. They create conflict, lead to neglect of work and create opportunities for corruption.

Abuse of per diems is related to pressures such as low pay, and opportunities created by weak controls especially in the public sector.

Health officials in low-income countries perceive that per diem policies and abuses unfairly benefit already well-connected and better-paid employees.

Reform of per diem policies is needed and should consider ways to mitigate pressures and close off opportunities for abuse, while promoting transparency and accountability.

The majority of respondents reported that per diems positively affect worker motivation, improve efficiency and make people work harder. Employees such as this mid-level Ugandan officer appreciate and respond positively to allowances:

“I put more effort in my work because an allowance shows that my work is recognized. With a motivated workforce, then an organization achieves its goals.”

One respondent described how he would not perform adequately or use the training content if he was not paid a per diem.

“We can be called for a workshop and if I find that there are no allowances, I lose concentration … When I come back here and find a case related to the training, I will say that I cannot treat that patient because I did not learn anything from that training. But if I get an allowance, I will be very grateful to help patients and as a result we can promote the health services. So allowances really motivate people to work hard.”

In addition to organizational advantages to per diems, most respondents agreed that there were personal benefits. Per diems allow employees to pay loans, take better care of family, meet monthly expenses or save for larger expenses. The increased revenue was important even for higher-level officials. A high-level Ugandan respondent described this issue:

“My Permanent Secretary earns less than 2 million after tax deductions yet he handles budgets of over 50 billion. Permanent Secretaries do a lot of work but they earn only 1.8 million. Pay reform has failed the government of Uganda.”

Respondents told stories of how allowances help pay basic necessities or allow for larger purchases:

“It helps to cater for some other things at home; they even help with things like paying school fees for children because the government salaries are very low. We do a lot of things with the money and it keeps us going mostly when it’s mid month.” (mid-level Malawian official)

“Allowances act as safety nets in case one has borrowed money. You can pay for daily utilities at home, give your children pocket money when they are going to school. You live comfortably at home if basic utilities are in place, for example, water, electricity, food … I save some money to look after my family. When you save, you can have a happy family.” (mid-level Ugandan official)

Officers from public and NGO sectors who travel to the field most frequently claimed to earn more from per diems than salary. For example, one Ugandan mid-level official claimed that he did not use his salary for 2 years because of the allowances he received. Within this time, he was able to build a house. Another high-level respondent was able to save 10 million UGX (US$5000) over a year, 1.6 times his regular salary.

Disadvantages

We asked informants about disadvantages and negative consequences of per diems (Box 2). Several key concerns were that per diems create conflict, change the organizational culture, lead to neglect of work and create opportunities for abuse.

Box 1 Organizational and personal advantages of per diems.

| Organizational benefits |

| Facilitate getting work done by paying necessary travel expenses |

| Encourage training, thus increasing knowledge base of the organization |

| Reduce absenteeism* |

| Increase staff motivation and productivity |

| Personal benefits |

| Provide additional salary for paying household expenses |

| Contribute to poverty reduction |

| Allow families to save for bigger items and pay back loans |

| Increase personal motivation |

Note: *Some informants thought per diems would reduce absenteeism because people who earn per diems feel well compensated and motivated to work. However, other informants felt per diems could increase absenteeism as staff would call in sick to attend workshops and earn per diems.

Box 2 Disadvantages of per diems.

| Criticisms of rates and payment modalities |

| Rates are too low, allowances are not paid or are not paid in timely manner. |

| Unfair differences in rates, unequal opportunities to earn allowances. |

| Inflexible policies do not allow adequate choice (e.g. prepaid accommodation). |

| Negative results or impact of per diems |

| Create conflict among staff. Those slighted may try to retaliate by not working as hard. |

| Costly to the organization and not sustainable (the travel which is fuelled by desire for per diems has other associated costs also, including fuel, car maintenance and airtime). |

| Create a negative organizational culture where people expect to get paid for every activity. |

| Lead to changes in allocation of time and neglect of management tasks or services not linked to allowances. |

| Foster manipulation of work practices (slowing work, over-scheduling trainings, creating temporary employment for friends or relatives to gain per diems, other fraud). |

| May exacerbate social problems (drinking, frequenting of prostitutes). |

Creates conflict

Several people observed that per diems create conflicts between people who are receiving allowances vs other team members. A Ugandan participant observed that “programme staff are more likely to go to the field, unlike those in administration and operations. This is de-motivating for staff who never get these allowances.” Conflicts were seen as harmful to team work.

“There are always quarrels … If I do not have a relative above, it means I will most of the time be left out.” (low-level Malawian worker)

“Officers who are highly connected do hijack activities that have a lot of allowances attached to them; this has resulted in internal conflicts that interfere with team work.” (mid-level Ugandan officer)

Staff without opportunities to attend workshops sometimes retaliate through malingering or absenteeism, as described by a mid-level Malawian officer: “those left out start to leave all the work to be done by the one who is attending the workshops, because they feel that they are not being recognized.”

Stimulates changes in mindset and culture

According to some participants, per diems have become engrained in the culture, resulting in a change in mentality. People have become so attached to them that it has system-wide effects on planning, budgeting and time allocation. A Malawian government official said that staff were reluctant to engage in even “very simple activities that could be done without any money going into it”. During the planning process, staff would ask to reorganize the activity “properly” so that they could increase the portion of the budget allocated to per diems. A high-level health officer in Malawi admitted that:

“Much as I have benefited from attending trainings and getting allowances, I think it is not a very good culture … we have created a culture where people expect to get something, from a workshop and the like … a situation whereby to give people knowledge, or for them to attend a meeting, we have to give them something. And that is not very healthy.”

In Uganda, an NGO manager pointed out a major disadvantage of a system where people are so “tuned in” to per diems: they will not work if there are no allowances. A mid-level Malawian respondent described how people might behave if invited to a workshop without allowances:

“If there is a workshop whereby people will receive no allowances, most people would not attend that workshop. Mostly during workshops they tell you logistics on the first day and if they just tell you that there is no allowance people would just attend the first session and then when they have a break they will disappear.”

Leads to neglect of certain kinds of work

Participants in both countries described how per diems influence allocation of time. Staff will work more on activities which have per diems associated with them, avoiding tasks that have no per diems. This tends to favour work in the field over normal service delivery tasks in facilities or office-based work such as planning, report writing and management functions. The result is that services are interrupted and management is not effective.

“Work that involves writing, concentrating on issues, analysing issues at the desk—things that will not attract an allowance—sometimes suffers because people want to go to the field. Because they know that there, they will get something.” (Malawian NGO officer)

“Many times [officers] exclude themselves from office work because they want to be in the field to get allowances. This delays reporting.” (low-level Ugandan officer)

In addition to neglecting certain types of work in order to get per diems, participants also expressed concern about abuse of position for private gain. These issues are discussed further in the next section.

Abuses

Government and NGO informants remarked on abuses (Table 3). Abuse seemed more common in the government sector, possibly because of low pay and weak controls. One Ugandan mid-level official explained, “with per diems from development partners, a receipt is expected for accountability. But for the government this is not the case.” Funds being abused in NGOs are largely from donors, but in the public sector, budget support from many donors is pooled into one basket, so both donor and government funds are vulnerable to abuse. In Uganda about 33% of the budget is funded through donor budget support (Government of Uganda 2009). Two types of abuses—double-dipping and shorting the driver—were only mentioned by informants in Uganda; however, based on personal observations the research team believes these practices may also take place in Malawi.

Table 3.

Examples of abuses

| Type of abuse | How it works | Illustrative quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Delaying duties | Work slowly or at weekends in order to increase overtime, lunch allowance, or per diem | There are times when people do not do their duties in time, so that they should look like they have worked over time or during lunch … Some other people will decide to come on the weekend because they want to get allowances, yet they are not supposed to. (high-level officer, Malawi) |

| If I am serious, that work can take me maybe 2 days; but I may dilly-dally that activity to take 5 days … one can delay deliberately just to increase the days … (high-level officer, Malawi) | ||

| Double-dipping | Getting allowances from two sources at the same time | Officers are always in Kampala attending more than one workshop a day, to just sign and be able to get that money … Many do get these same allowances at their district (their duty station). Therefore, they do get double allowances. (mid-level officer, Uganda) |

| Exaggerating days | Over-estimating the time it will take to complete a job, so as to make more on per diem | There is a tendency for staff to plan for as many nights and field days as possible … officers plan for field visits from Monday to Friday. Then you wonder when they sit at their desks. (NGO officer, Uganda) |

| Other staff members do plan for more days to carry out activities … especially now that we are going into Christmas season. People have to make some money for that period. (NGO officer, Uganda) | ||

| Skimming days | Doing work in less time than budgeted, or not completing work, but keeping the full per diem | Sometimes they go to the field and come back earlier than planned and don’t report for work, so as to make it look like they are still in the field and still claim all the days that were put on paper. (NGO officer, Malawi) |

| Some officers lie that they have travelled, when they haven’t. Some officers request for allowances for 7 days, but in actual sense work for 2 days. (high-level officer, Uganda) | ||

| Shorting the driver | Pocketing per diems meant for other staff | Officers in higher positions cut the amounts of allowances we are meant to get. (low-level officer, Uganda) |

| Workshop fraud | Falsifying participant lists, keeping per diems not disbursed | Ghost participants are included on attendance lists … Instead of having workshops on different days, they merge them into one such that they save allowances for themselves. (NGO officer, Uganda) |

Exaggerating or skimming days

In a common strategy, upper-level staff might pad per diem estimates in the work plan. An NGO staff member in Malawi explained:

“Staff can overstate the amount of days that will be required to do a task. They take advantage that they are the ones that are planning, and usually can overstate workload and number of days, when in fact the workload cannot take that much [time].”

Another NGO official in Malawi noted that people might split up tasks to maximize per diems: for example, a supervisor may visit the same place four separate times when she could have done all the activities in one trip. A related strategy is to work fewer days than the work was budgeted for, but still claim the full amount of the per diem. Participants often described such “skimming” as deliberate, as shown in these quotes:

“One can speed up a workshop which is meant to be 5 days and do it in 3 days so that you can make a saving. There is sometimes no mechanism to find out.”

“Officers … call district officials to forge receipts, in order to show that activities were carried out even when they were not.”

Another way of skimming days is by taking a per diem which was intended for others; for example, bosses sometimes do not give drivers their per diems. One Ugandan driver reported:

“[Our bosses] plan for 2 weeks, then give us allowances for only a week. It is these bosses that draft the payment sheet where we sign. You only put your name and signature on this payment sheet but are never allowed to record the number of days you have worked. If you ever complain about the [unpaid] allowances, you are told that the money has not been disbursed.”

Workshop jumping and attendance fraud

Workshop jumping is the practice of attending workshops just to gain per diems—sometimes multiple workshops in one day. A mid-level Malawian informant described staff calling in sick so that they can attend a workshop: “if there is a workshop that is paying K2500 per day, people would rather give an excuse like ‘I am off duty today’ or ‘I am sick’ so they can go.”

In some cases the abuses involve fraud such as registering participants who were not actually in attendance. A Malawian informant described how a district nursing officer might plan a week-long training for 30 nurses but only invite 10 nurses or conduct the training in fewer days to keep the per diems. In Uganda, several informants described the inclusion of “ghost participants” on attendance lists for training workshops or re-using an attendance list from a different workshop to justify per diems. Mid-level officials in both countries pointed to abuse by officers who pay the per diems:

“They forge signatures for [those] who did not come and save that money for themselves. It is not surprising that accounting officers fight to go and pay participants who have attended a workshop. If it is a big workshop, an officer can save between 3–4 million shillings.”

In Uganda, informants suggested that accounts officers or senior officials may extort kickbacks from workshop participants as per diem payments are made. One informant described how supervisors who are responsible for allocating staff to activities may also “crack deals” so that the supervisor gets a portion of the officer’s per diem. Another type of kickback involved hotel arrangements: staff booking rooms for a workshop may collude with the hotel to inflate prices and share the illicit gains.

One Malawian NGO representative thought that staff attending workshops or meetings just to make money is less likely to happen in NGOs because of the organizational culture:

“If there are systems to check, good co-ordination, and the one who is approving the trips is doing it well, then it cannot be an issue. This is a problem in places like government, where people are free to do what they like and there is not much monitoring.”

In Uganda, a government informant agreed that officers do jump from one workshop to another in order to gain extra per diem. However, another informant stated that good team work inhibited this practice:

“In our department there is no workshop jumping since we work as a team. We do enough planning before implementing an activity. There is no way a person can be tagged to be in two different workshops at the same time, unless they have presentations to make in both of these workshops.”

Favouritism and upper-level abuses

Several informants mentioned that people who are related to managers may get more opportunities, and that senior staff may be allowed to benefit from training opportunities meant for junior staff.

“Some senior officers send their friends or tribe mates to workshops up country where they are expected to earn more allowances. Those not favoured by the system are usually sent to Kampala where they get a very small subsistence allowance, or to those workshops that have prepaid hotel fees where one is likely to earn little or nothing—no possibility to save.”

In Uganda, a mid-level official stated that “officers tag your name to certain activities, but they never tell you. So that means they take advantage of your allowances.” The official noted that he would only learn about the activity when it was reported in a meeting. “What I wonder about sometimes,” he mused, “is where they get my signature to show receipt of those allowances.”

Informants resented “self-dealing” by officials, that is, taking advantage of one’s position in transactions and acting for one’s own interests instead of the interests of the organization or beneficiaries. A mid-level Malawian official noted that her bosses “benefit a lot because … they are in positions where they can access allowances easily. It can help them do a lot of things like building houses and buying cars.” In Uganda, a driver complained that “top officers do what they feel like and they are not cautioned,” while other informants expressed suspicion that their bosses “play around”, hiding budget details so it is hard to know where the funds have gone.

Factors associated with abuses

As shown in Table 4, informants mentioned many factors leading to abuses of per diems, including low salaries, difficulties saving money, and inadequate monitoring or lack of accountability. In addition, donor-related incentives and weak moral character were seen as associated with abuse.

Table 4.

Pressures, incentives and opportunities for abuse

| Factor | Illustrative quote |

|---|---|

| Low salary | The basic pay is terrible, so abuse of these allowances is not surprising. (high-level officer, Uganda) |

| High prices | The prices of everything nowadays have gone up. (mid-level officer, Uganda) |

| Difficulties saving | They are trying to save money to boost their basic income. (high-level officer, Uganda) |

| Inadequate monitoring | There is monitoring, but the monitoring can have limitations … My controlling officer may not be able to know that I am [delaying an activity] deliberately just to increase days. (high-level officer, Malawi) |

| You find people claiming for allowances but they have not done anything to deserve allowances … you find that people around them know what is happening, but they just let it go. People do not air these [things] out … And I feel this is not going to help us in any way. (NGO officer, Malawi) | |

| Lack of accountability | If an allowance is taken before the job is done, and due to other circumstances the job has not taken place, sometimes it has been difficult for people to return the money. (NGO officer, Malawi) |

| Sometimes people may stay less time in the field because the work that was planned was finished earlier. People may not want to give [allowances] back to the office because maybe they had even used the money already. Maybe they left the money for their family at home, or they bought some things while in the field. (low-level officer, Uganda) | |

| It is managers who are incompetent; why would you approve 6 nights when the work is supposed to be for 2 nights? If you approved the budget as a manager, then what is your problem if I spend all the money? (mid-level officer, Uganda) | |

| Weak character | It is bad here in the Ministry. Top officials are very greedy. (low-level officer, Uganda) |

| Donor incentives | How are donors going to make sure they spend all the money? It is through giving out more allowances. (NGO officer, Malawi) |

Participants’ suggestions for solutions

Informants made several suggestions about how problems with per diems could be reduced. Increasing salaries of workers and paying them on time was considered most important, since low salaries and late payment create pressure on workers to make money through abuse of per diem policies.

“It is like saying that if a woman does not give birth to a girl she will give birth to a boy. It is an obvious statement: to curb allowance abuse, increase basic pay of government employees.”

Some informants also argued for harmonizing per diem rates across organizations, noting that differences in rates foster competition rather than collaboration among development partners, and create mismatched expectations.

A second set of solutions proposed by informants centred on improving the policy design process. Informants emphasized the value of comparative analysis to determine best practices in setting the rules for giving out per diems and managing their distribution. In proposing solutions, informants often mentioned the need to involve more people in the discussions. As one person noted:

“There has to be a participatory process in terms of developing allowance policies. The staff, managers and administrators have to agree on putting up a system that is efficient, effective and that helps achieve the organization’s objectives.”

Thirdly, informants recommended enhanced monitoring, complaint mechanisms and enforcement. An NGO informant in Uganda observed that it is folly to expect people to act with integrity if there are no checks and balances: “in some organizations you find that there is one person who approves the budget, signs the budget and approves allowance requests. Why wouldn’t such a person take advantage of this for his or her own gain?” Government informants in Uganda thought that the procedures allowing senior government staff to sign for per diems on behalf of junior staff should be abolished. They also thought there should be mechanisms for raising complaints, along with punishment for wrong-doers:

“Officers have selfish interests and as a result give us less than what we are supposed to receive. If only there were meetings to address our complaints.”

“People should be tagged as responsible persons for activities. There should be room for cautioning if they misappropriate allowance funds.”

Many people believed that abuses could be controlled through improved planning and technology solutions. Several noted that if you schedule workshops to occur one at a time, then people cannot workshop jump. A high-level informant in Malawi felt computerized systems would allow quick searching of records to assure that policies were being applied correctly, while a low-level government informant in Uganda advocated direct payment of per diems into employee bank accounts as a way to prevent “the thieving cycle which enables officers to conduct workshops from their office desks.” Informants felt that more formal systems for allocating opportunities would control the ability of managers to favour themselves or their friends or relatives:

“I worked in a hospital where there was a system. The manager would have a book. All those that have gone to a particular training would be written down, so if there is a next training those people would not be considered unless it is very, very important within their section that they went for another training.”

Participants who perceived abuses of per diems as mainly a moral problem were likely to see the solution in interventions to promote integrity. One mid-level informant in Malawi felt that frequent transfers of staff might help to avoid entrenchment of low standards of integrity, while other informants pointed to the need for honest leaders and integrity training.

“We had a Permanent Secretary here who had changed the allowance system. Drivers would get their allowances on time. We had meetings to share experiences and challenges. He was hated by many officers, and it is no wonder that he was shifted from this ministry.”

Many informants pointed to the role of transparency in controlling abuses. A mid-level Ugandan government official felt that officials should learn to be more open, displaying annual work plans on notice boards and communicating with staff about activities in a timely way. This might help to avoid poorly attended workshops which create an opportunity for accounts staff to abscond with per diems.

Several Ugandan officials agreed that the dissemination of allowance circulars was essential so that staff members understand their rights. Yet, even if staff had access to per diem rate information and budget amounts, informants thought they would need to become more proactive if they did not want to be cheated.

Discussion and policy implications

This study is one of the first attempts to understand the causes and consequences of abuse of per diems. Exploring this topic through qualitative research is critical, as ‘Any explanation of behavior which excludes what the actors themselves know, how they define their actions, remains a partial explanation that distorts the human situation’ (Spradley 1979). An important purpose of per diem policies is to reimburse staff for work-related expenses for travel and training events. However, it is clear from our study that per diems also have other tacit purposes, including providing salary support to individuals and their families. For many health care workers, the revenue from per diems was an integral part of household budgeting and long-term financial planning—per diems were used to support daily expenses, pay back loans, fund periodic expenses such as school fees, and save for larger investments such as home construction. In the context of low government salaries, per diems helped even the low-level public workers to feel that they could provide for their families.

Yet, per diems also had perceived drawbacks and had created discontent. Particularly in the government sector, per diems were perceived to provide financial advantage to already better-off and well-connected staff. These perceptions about favouritism are consistent with political economies that are organized around patron–client relations and obligations of social reciprocity, where decisions about opportunities for training and travel are more political and personal than they are rational (Smith 2003). At the same time, participants in our study seemed to feel that high officials were enriching themselves but not sharing their gains in ways that social reciprocity demanded. People especially distrusted officials in positions where they had little interaction (e.g. the accounts department), supporting the idea that social distance is predictive of perceived illegitimacy of actions (Smith 2007).

Many respondents felt that per diems had created a negative organizational culture where public servants or NGO officials were constantly seeking to be paid for participation in activities. This led to neglect of those activities which were not associated with allowances. In many instances the competition to win per diem revenue, coupled with power imbalances in organizational structures, led to conflict and employee dissatisfaction, possibly counteracting the positive effects of allowances.

Theory of corruption suggests that patterns of abuse vary depending on opportunities, pressures and incentives (Vian 2008). In this study, abuses were associated with environments of weak planning, monitoring and enforcement; pressures of low salaries, poor working conditions and the need for savings; and incentives of greed and desire to steer revenue-earning opportunities to friends and relatives. Some informants also mentioned pressures created by donors, including competition to get people to attend workshops or meetings, and the pressure to spend large sums of money quickly. “If you removed allowances for the donor activities, you would not see any work,” said a mid-level Ugandan informant. This may cause donors to offer high per diem rates as an incentive. In addition, donors tend to favour activities such as training which are seen as capacity strengthening. When donors are operating under tight deadlines, they tend to increase spending on these allowance-related activities. So while participants perceived that NGO organizations spending donor funds are less vulnerable to abuse because of greater control systems and higher salaries, they also saw donor funding itself as a factor in increasing pressures to abuse allowances.

It is plausible that the pressure of supporting kinship-based extended families could also be a contributing factor in escalating the abuses, as many people in our study mentioned family needs in relation to allowances. A similar finding was presented in a recent Ugandan study (Bukuluki et al. 2010). Many participants in that study believed that corruption, including taking bribes or selling government-issued drugs for private gain, was not morally reprehensible if the proceeds were shared with one’s in-group or extended family.

Our study found that perceptions of per diems were fairly consistent between the two countries and among levels of staff. Although lower-level staff expressed distrust of higher-level staff, they all agreed that higher-level staff do have greater opportunities to abuse. In our study, abuses seemed to be less severe in NGOs, possibly due to higher salaries, more performance-based organizational culture, and because NGOs seemed to have stronger management controls. NGO informants pointed to: checks in the system which would not allow staff to “invent reasons” to go to the field; staff co-ordination which means that the person approving a trip is generally well-informed about project activities; and requirements for receipts. In addition, NGOs generally give the same per diem rate to all cadres and may have a lower ratio of per diem to daily wage compared with a higher ratio (e.g. 9:1) among some government cadres.

Most study participants saw abuse of allowances according to economic models of corruption, i.e. that officials weigh the benefits and costs of alternative actions when deciding whether to engage in abuse or not. By this model, policy reform should consider systemic changes in ex ante incentives for acting with integrity, reducing the pressures which lead to abuse, and increasing the cost to officials of engaging in fraud. Examples of these strategies include implementing modern performance assessment systems and performance-based pay, increasing transparency of budgets and per diem pay-outs, and increasing the likelihood that people who abuse allowance policies will be caught and punished (Kaufman 1998; Klitgaard et al. 2000). Many of these strategies were mentioned by the informants themselves.

At the same time, study participants were distressed by the lack of morality exhibited by people who abused the system. Perceptions of morality were complex and seemed tied with how the proceeds from allowances were used or shared. People hold conflicting beliefs at the same time: it is bad for powerful people to abuse allowances, but not so bad if they share the proceeds fairly, i.e. not just with their ‘in group’. This suggests that people may be appealing to morality when they feel left out, or when a public official ‘eats alone’. Daniel Jordan Smith’s work in Nigeria found that people equate corruption with decline in morality because they believe that morality should ‘privilege people and the obligations of social relationships above the naked pursuit of riches’ (Smith 2007, p. 138) Judgments of morality and corruption are therefore linked with perceptions of equity and reciprocity. More work is needed in this area to try to build on people’s expressed desire to curb abuses, while also recognizing the complexity of attitudes toward corruption, equity and social obligation.

Organizational culture was seen as amenable to change through the selection and promotion of good leadership and personal moral decision-making: several informants gave examples of good leaders who had implemented changes to reduce abuses. In developing public policy it is important to consider both the economic and the moral perspectives.

Our study has limitations. First, in answering our questions, informants sometimes spoke about personal experience but also discussed practices in cultural terms: “What people here do.” While this is valid data for a qualitative study using grounded theory methods, the findings do not provide evidence of the prevalence or scope of these practices. In addition, our study was not intended to be a comprehensive policy review which would require additional information. For example, we cannot quantify the amount of spending on per diems, either by donors or in the government sector, and we do not know the size of possible losses due to abuse. These are topics for future study.

In future work, it will be important to examine per diem reform options in light of existing regulatory structures and the macro-economic context (Conteh and Kingori 2010). Countries which are more reliant on donor funding or which have weaker regulatory structures in place may need to sequence interventions in specific ways. Important country or health sector data and performance indicators to consider include national spending on per diems compared with other categories of health expenditure; per diem rates compared with per capita income; and current control procedures being used in different organizations.

The policy reform process should include participation from staff, managers and administrators, as well as donors and policy makers. Our study showed that officers at all levels of the system are likely to have ideas on how to reform the system to be more equitable and to reduce opportunities for abuse. Government and donors must consider how to generate greater participation without reinforcing the per diem incentive: in other words, meetings to discuss per diem reform should not be occasions to earn per diems. Technology may help to avoid this problem while encouraging voice: for example, web sites where staff can post opinions or experiences, online polls, ‘quizzes’ to gauge understanding of current policies, etc. Open ‘town hall’ meetings may be another way to allow staff to express concerns and suggest solutions. Reforms should recognize that the roles and contributions of NGOs and development partners should be aligned with government institutions, perhaps through standardized rates and procedures. Such solutions may be harder to implement but would better manage incentives.

Development partners can support reform in several ways, including facilitating discussion of reform through existing co-ordination mechanisms, supporting the development of policy analysis tools, and health systems strengthening through automated payment systems, fraud control checks and training databases. Donors could also support baseline data collection needed for policy analysis for the design of reforms in countries where this issue is a priority, and evaluate pilot interventions to demonstrate effectiveness.

Funding

Funding for this study was provided by the U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Center operated by the Chr. Michelsen Institute, Bergen, Norway. U4 and the Center for Global Health and Development also supported the cost of free online access to this article. The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of U4, its partner agencies, or Chr. Michelsen Institute.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the assistance of Hilda Namutebi, from Makerere University in Uganda, who helped to conduct interviews, and Ivan Busulwa, MBA-MPH, Boston University, who assisted in data analysis. Frank (Rich) Feeley, JD, provided helpful comments on a previous draft of this article.

References

- Bukuluki P, Ssengendo J, Byansi P, Mafigiri D. 2010. Governance, Transparency, and Accountability in the Health Sector in Uganda. Country Study Report (TISDA Study). Kampala, Uganda: Transparency International Uganda. [Google Scholar]

- Chêne M. Low salaries, the culture of per diems and corruption. U4 Expert answer. 2009. Online at: http://www.u4.no/helpdesk/helpdesk/query.cfm?id=220, accessed 3 August 2010.

- CIA. The World Fact Book. 2011. Online at: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/, accessed 6 December 2011.

- Conteh L, Kingori P. Per diems in Africa: a counter-argument. Tropical Medicine and International Health. 2010;15:1553–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW. Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Uganda. 2009. Budget Speech Fiscal Year 2009/2010. Delivered to 8th Parliament of Uganda by Hon. Syda N M Bbumba, Minister of Finance, Planning, and Economic Development, on 11 June 2009, Kampala, Uganda. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen EG. 2009. Does aid work? Reflections on a natural resource programme in Tanzania. U4 Issue 2009: 2. Bergen, Norway: U4.

- Kaufman D. Corruption and Integrity Improvement Initiatives in Developing Countries. New York: United Nations Development Programme (UNDP); 1998. Revisiting anti-corruption strategies: tilt towards incentive-driven approaches? In UNDP. [Google Scholar]

- Klitgaard R, Maclean-Abaroa R, Parris HL. Corrupt Cities: A Practical Guide to Cure and Prevention. Oakland, CA and Washington, DC: ICS Press and World Bank Institute; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Policy Forum. 2009. Reforming allowances: a win-win approach to improving service delivery, higher salaries for civil servants and saving money. Policy Brief 9.09. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: Policy Forum. [Google Scholar]

- Ridde V. Per diems undermine health interventions, systems and research in Africa: burying our heads in the sand. Editorial. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 2010 doi: 10.1111/tmi.2607. Jul 28 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roenen C, Ferrinho P, Van Dormael M, et al. How African doctors make ends meet: an exploration. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 1997;2:127–35. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1997.d01-240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DJ. Patronage, per diems and the ‘workshop mentality’: the practice of family planning programs in Southeastern Nigeria. World Development. 2003;31:703–15. [Google Scholar]

- Smith DJ. A Culture of Corruption: Everyday Deception and Popular Discontent in Nigeria. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Spradley JP. The Ethnographic Interview. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Group; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Vian T. Review of corruption in the health sector: theory, methods and interventions. Health Policy and Planning. 2008;23:83–94. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czm048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vian T. 2009. Benefits and drawbacks of per diems: do allowances distort good governance in the health sector? U4 Brief No. 29. November 2009. Bergen, Norway: CMI, U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.