Abstract

Interprofessional education is broadly defined as a teaching and learning process that fosters collaborative work between two or more health care professions. Interprofessional education, as a proven, beneficial approach to collaborative learning that addresses the problems of fragmentation in health care delivery and separation among health care professionals, is frequently promulgated but not always successfully implemented. Furthermore, there are several different interpretations, overlapping terminologies, interchangeable terms, and a lack of uniformity of a definition for interprofessional education. This concept analysis determines the attributes and characteristics of interprofessional education, develops an operational definition that fits all health-related disciplines, defines common goals, and improves overall clarity, consensus, consistency, and understanding of interprofessional education among educators, professionals, and researchers. Through effective incorporation of interprofessional education into curricular and practice settings, optimal patient-centered outcomes can potentially result as effective and highly integrated teams facilitate and optimize collaborative patient care and safety.

Keywords: health professions education, collaborative learning, curriculum, patient care, health care services

Introduction

Chinn and Kramer define a concept as “a complex mental formulation of experience”.1 “Concepts contain attributes or characteristics that make them unique from other concepts”.2 Concept analysis seeks to determine structure, function, attributes, and characteristics of a concept which serves to provide common understanding of the term so that future research endeavors find the concept clearly communicable and increasingly measurable.

The purpose of this analysis is to explore the concept of interprofessional education (IPE). IPE is not a new concept to health care professionals, although it is a topic of current interest and extensive discussion and debate. A comprehensive literature review of this complex concept reveals that there are several different interpretations, overlapping terminologies, interchangeable terms, and a lack of uniformity of a definition for IPE. This general lack of clarity contributes to continued misunderstanding and obstacles to optimal IPE implementation.

Understanding how IPE affects health care professionals’ ability to work together effectively has tremendous significance, since collaboration and highly integrated teamwork are essential to patient safety and quality of care. Conversely, lack of coordinated teamwork and communication breakdowns can lead to fatal errors in patient management.3–7 Determining a clear, operational definition of IPE across health care disciplines will contribute to more effective IPE design, delivery, and measurement.

Objectives of the analysis

The objectives of this concept analysis are: 1) To determine the attributes and characteristics of IPE; and 2) to develop an operational definition of IPE within the context of health professional education that fits all disciplines, defines common goals, and is sufficiently detailed so as to minimize conflicting or differing interpretations. A modified version of Walker and Avant’s2 concept analysis method will be utilized to satisfy these aims.

Descriptions of the IPE concept

There is no definition for IPE in the English dictionary, and there are no dictionary or encyclopedia definitions for interprofessional or interprofessionality. Education is defined by Merriam-Webster8 as the action or process of knowledge development.

The World Health Organization states that IPE “occurs when two or more professionals learn about, from, and with each other to enable effective collaboration and improve health outcomes”.9

The Center for Advancement of IPE (CAIPE) defines IPE as “a teaching and learning process that fosters collaborative work and improves quality of care between two or more professions.10 IPE occurs when students learn with, from, and about one another”. This definition has also been adopted by the Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative (CIHC) and seems to be the most widely accepted definition.11 The CIHC adds that IPE occurs when health care professionals learn collaboratively within and across disciplines to acquire knowledge, skills, and values needed for working in teams.

The Interprofessional Education for Collaborative Patient-Centered Practice (IECPCP) defines IPE as learning together to promote collaboration, and it elucidates three components to IPE: 1) socializing health care professionals to work together; 2) developing mutual understanding and respect for various disciplines, and; 3) imparting collaborative practice competencies.12

There are two relatively new biomedical journals that concentrate on IPE. The Journal of Research in Interprofessional Education13 has adopted the CAIPE definition. The Journal of Interprofessional Care14 does not describe or refer to a preferred definition. However, one of the journal’s joint editors-in-chief, Hugh Barr, applies competencies to describe IPE.15 He notes how relationships are strengthened as professionals begin to understand their own roles and the roles of others better, which eliminates stereotypes and generates mutual trust. He describes IPE as a rewarding experience that improves collaborative practice and which may be transferred to other members of the health care team. The competencies Barr describes are derived from England’s National Occupational Standards in Professional Education and are based on “key roles” that speak to developing professionalism, research, and relationships; promoting effective communication; prioritizing values that promote the rights, responsibilities, and diversity of others; becoming a reflective practitioner; optimizing health (physical and social); patient empowerment; ongoing assessment; and care planning.16

Antecedents

IPE is preceded by issues related to patient safety and quality of care. Furthermore, workforce shortages contribute to the lack of collaborative practice, lack of patient-centered care, and lack of knowledge related to professional roles in health care. Collaborative medical education was identified as an essential element in health care by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 1988 with its conceptual framework for multiprofessional education for health personnel.17 WHO has continued to assess IPE efforts, identify IPE gaps, IPE organizations, and research contributions to IPE and in 2007 issued its study group report on IPE and collaborative practice.18

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) has issued two reports concluding that all health care student education should focus on patient-centered care. The first, Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century (2001), recommends that all health professional students should receive education and training in interdisciplinary teams related to collaborative care.19 The second publication, Health Professions Education: A Bridge to Quality Care (2003), identified five competencies that relate to all health care disciplines: provide patient-centered care; work in interdisciplinary teams; employ evidence-based practice; apply quality improvement; and utilize informatics.20 The IOM concludes that health care professionals must competently deliver patient-centered care in interdisciplinary teams.

In order for IPE to occur, there must be willingness on the part of all health care professionals to change the way they educate and practice. This requires shifts in tradition, education, and practice which will ultimately result in changing the current health care paradigm.

IPE Facilitators

Accrediting bodies and organizations concerned about health professional education are among the powerful forces behind the promulgation of IPE. These entities have the capability of requiring evidence of structured IPE activity and monitoring for collaborative practice.

The Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME) states that medical education programs must integrate the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) competencies into their curricula.21 One of the six ACGME competencies involves “interpersonal and communication skills that result in the effective exchange of information and collaboration with patients, their families, and health professionals”. The competencies also include “systems based practice” where students are expected to “demonstrate an awareness of and responsiveness to the larger context of health care as well as the ability to call effectively on other resources in the system to provide optimal care”.22

The National League for Nursing Accreditation Commission (NLNAC)23 and the Commission on Collegiate Nursing Education (CCNE)24 agree that nursing programs must provide evidence of interprofessional collaboration in interprofessional teams and during patient care activities. The American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN) advises that one way of collaborating with other professions is to share simulation centers and their inventories.25

The American Dental Education Association (ADEA) advises that the work of other professionals in health care should be respected and valued.26 The Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) stresses interprofessional teamwork and learning throughout their guidelines.27 Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) president, Dr Darrell Kirch, states that IPE and practice has been designated as a key strategic area that will be vital to the culture of physicians, and he agrees with AACN that simulation center inventories should be shared.28

Other organizations with initiatives involving the development and incorporation of IPE into educational and practice arenas include the IECPCP,7 the National Health Service,29 and the Association for Prevention Teaching and Research (APTR).30 IPE forms relationships and strategic alliances between professions that have tremendous merit and professional program benefits, and promote joint ventures such as research ventures between disciplines.

IPE has become more accepted and widespread in Canada and the UK than it is in the US. In this country, there are presently five Centers for IPE including the University of Washington, the University of Minnesota, Thomas Jefferson University, Saint Louis University, and Creighton University. There is only one regional model of IPE in the US. Founded by The Commonwealth Medical College, the Northeast Pennsylvania Interprofessional Education Coalition (NEPA IPEC) is a cooperative effort of 20 colleges and universities, and postgraduate education programs committed to IPE.31,32

Defining attributes

After a comprehensive review of the literature, we have identified the defining attributes of IPE. Critical descriptors are presented to elicit a mental image of the phenomena of IPE. For IPE to be present, there must be: 1) Active involvement (interactional) by two or more members of a health care team who participate in either patient assessment and/or management; 2) an experiential learning and socialization process; 3) a process where participants learn with, from, and about one another, both within and across disciplines, via the experience itself; 4) andragogical (nonhierarchical and de-centered) experiences; 5) a knowledge and value sharing process, and; 6) collaborative patient-centered care that strives for optimal health outcomes that are not content- or subject matter-driven.

Professions that participate in IPE include but are not limited to: nursing (including nurse practitioners or nurses with advanced degrees), medicine, pharmacy, social work, nutrition, physical therapy, occupational therapy, counseling, physician assistant, dentistry, emergency medical services including paramedics, radiology professionals, and respiratory care professionals. Any medical or allied health professional that engages in patient assessment, care, and/or management may be included in IPE.

Concept map

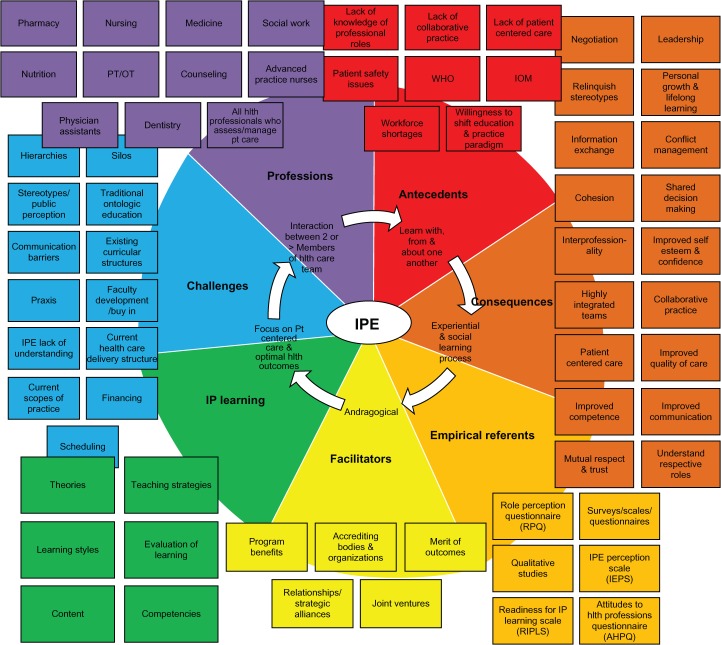

A “color wheel” concept map depiction of IPE is shown in Figure 1. Attributes, antecedents, consequences, empirical referents, challenges, facilitators, learning types, and professions are represented. The iterative “color wheel” representation was chosen because of its ability to display colors/characteristics of IPE as possessing the ability to shift and mix with other colors/characteristics to describe the concept’s multidimensional potential. The “color wheel” is a reflection of knowledge development, research, and functional implications of IPE.

Figure 1.

Iterative “color wheel” concept map for interprofessional education (IPE).

A “color wheel” discloses the visible color spectrum. The colors that presently characterize IPE are, thus far, the visible ones identified by us and depicted in this model. However, it is possible that this concept will grow and change, or perhaps other “colors” exist but just cannot be seen or identified yet. New perceptions and perspectives may alter this “color wheel” in the future.

Related concepts

The concepts most closely related to IPE include interdisciplinary education and multidisciplinary education. Illustrated representations of interprofessional, interdisciplinary, and multidisciplinary practice are shown in Figure 2. Merriam-Webster defines interdisciplinary as the involvement of two or more disciplines that share information and decisions together.33 However, in an interdisciplinary representation (Figure 2) there is interaction between professions but little, if any, sharing of values or knowledge. Interdisciplinary education lacks a clear process and coordination of education of the disciplines since, although the disciplines practice together, they are not truly collaborative and integrated with priority focus on the patient. Care is not necessarily patient-centered and each circle stands alone indicating that professions implement separately and are separately accountable.

Figure 2.

Illustration of operationalized terms related to interprofessional education (IPE0).

The term multidisciplinary is a very vague concept. Multidisciplinary is described by Merriam-Webster as “of or relating to or making use of several disciplines at once”.34 Multidisciplinary implies a coexistence of several disciplines where participants work side-by-side but separately and without substantial interaction. Differing emphases within a multidisciplinary approach may be an impediment to practice or teaching effectiveness. In a multidisciplinary representation, again, each circle stands alone indicating separate accountability (Figure 2). There is no sharing between disciplines in multidisciplinary practice. Disciplines are interacting with the patient but not with one another.

In contrast, IPE implies shared goals, a common learning process, coordination of teaching efforts, and shared decision-making and accountability. In the representation of IPE, discipline circles are interlocked, including an interlocking with the patient circle (Figure 2). Circles do not stand alone. There are shared values, shared knowledge, and shared decision making. All disciplines work in concert with one another. The patient has the largest, middle circle because all care is patient-centered. IPE is a transparent blend of disciplines coming together with shared goals.

“Shared learning” is a term that is sometimes incorrectly used to mean IPE. We could find no formal definition for this concept; although the term implies that students learn together, it does not specify the manner in which learning occurs.

D’Amour and Oandasan examined the concept of interprofessionality and write about its clear distinction from interdisciplinality.35 They propose interprofessionality as a new or emerging concept and describe it at a “cohesive practice” between disciplines. They state it is a “process by which professionals reflect on and develop ways of practicing that provides an integrated and cohesive answer to the needs of the client/family/population”. In contrast, they describe interdisciplinality as “a sum of organized knowledge, and the emergence of numerous disciplines” that … “has resulted in an artificial division of knowledge that does not match the needs of the researchers” who investigate IPE.

Consequences of interprofessional learning

Interprofessional learning is the most important direct consequence and goal of IPE. A combination of different learning theories apply to IPE including cognitivism (where information is processed and thoughtful decisions are made by stimulating cognitive processes), constructivism (where meaning and knowledge are created from experience through discussions and shared problem-solving), and humanism (where meaning contributes to learning because it corresponds with personal needs and goals). In drawing from cognitive and affective domains, Billings and Halstead describe IPE as follows: “Knowledge, ideas, attitudes and values are developed as a result of relationships with people”.36

Processes required to generate effective IPE include: cognitive processes, reflective processes, problem-solving, critical thinking, the development of trust relationships, and the fostering of curiosity. Interprofessional learning components consist of experiential learning (where knowledge is created through experiences), and social learning (where learning is a social activity). “This approach (IPE) to education suggests that the insights and skills acquired by the participants in an interprofessional experience are the learning itself”.37

Interactive IPE teaching methodologies may include: simulation, role play, problem-based learning, and small group learning. The preferred approach to IPE is an andragogical one where students learn in a nonhierarchical, de-centered environment. Interprofessional learning content may be presented either intracurricularly (embedded into curriculum) or extracurricularly (existing outside of regular class hours). An intracurricular approach may pave the way for an intracurricular approach at a later stage. IPE content may include diverse topics from simple communication among professionals and knowledge about specific health care professions, to complex discussions of culturally sensitive or ethical issues.

Evaluation of interprofessional learning is evidenced by a change in knowledge, attitudes, behaviors, beliefs, and/or skills. Since the focus of IPE is on interaction rather than specific content, and reflection, journals, or concept maps are good examples of how interprofessional learning may be evaluated. Achieving competencies is also evidence of interprofessional learning.

We can determine 18 consequences of IPE. Through IPE, learners: 1) gain negotiation, 2) leadership, 3) teamwork, and 4) improved communication skills. They become better able and prepared, 5) to exchange knowledge and information, 6) share decision-making, 7) manage conflict, and 8) provide patient-centered care through a better understanding of respective roles. Evidence also suggests that interprofessional learners have 9) improved self-esteem, 10) improved self-confidence, and 11) improved competence in practice.

IPE 12) fosters mutual respect and 13) mutual trust between health care professionals, 14) improves quality of care, and 15) makes health care teams cohesive by relinquishing stereotypes. Furthermore, 16) lifelong learning and 17) personal growth are also benefits or consequences of IPE. Ultimately, the most desired consequence of IPE is 18) collaborative practice.

Operational definition

In this concept analysis, IPE is proposed as an andragogical, interactive, experiential learning, and socialization process. IPE occurs when two or more members of a health care team (who participate in either patient assessment and/or management) learn with, from, and about each other as they collaboratively focus on patient-centered care and achieving optimal health outcomes. In IPE, knowledge and value-sharing occur within and across disciplines.

Empirical referents

Some of the empirical referents that have been used to measure and evaluate IPE delivery and outcome include the RPQ (Role Perception Questionnaire),38 the RIPLS (Readiness for Interprofessional Learning Scale),39–42 the IEPS (Interprofessional Education Perception Scale),43 and the AHPQ (Attitudes to Health Professions Questionnaire).44 In order to determine how various professions are interacting and perceiving one another, these scales ask questions related to interactions with other professionals, cooperative efforts, contributions from other perceptions, and whether individuals feel respected by other professions. Primarily, Likert scales, questionnaires, and surveys are used. IPE can also be evaluated using qualitative research methodologies. For example, Lidskog used a phenomenological approach to analyze interviews of students regarding perceptions of their own profession and the professions of others.45

Integrating a curriculum is a complex process, and it is differentially understood and experienced by students and faculty.46 In examining perception of instructional method and content by student learners, Curran and colleagues conducted an evaluation survey of 520 undergraduate health professional students from medicine (n = 61), nursing (n = 351), pharmacy (n = 20), and social work (n = 89).47 They found that face-to-face, case-based learning resulted in greater satisfaction than other learning methods, and they highlighted the importance of effective facilitation of small-group collaborative learning to enhance student satisfaction with interprofessional learning experiences. Two innovative IPE teaching strategies include deliberative discussion48 and guided reflection49 in each health profession group’s analysis of the case presented.

The clinical teamwork training inherent in a shared curriculum can increase interprofessional competence, defined as knowledge and understanding of their own and the other team members’ professional roles, comprehension of communication and teamwork and collaboration in taking care of patients.50–56 As a team-based approach, IPE relies significantly on student leaders in helping guide their peers through the learning process. Hoffman and coworkers used an evidence-based review of the literature and a questionnaire administered to Canada’s top student leaders and determined that student leadership is essential to the success of IPE because it enhances students’ willingness to collaborate, and facilitates the long-term sustainability of IPE efforts.57

Health sciences educators continue to debate the optimal timing for introducing IPE into the academic training of health professionals, although evidence-based IPE continues to be offered at increasingly early stages in students’ professional development. The University of Liverpool piloted an evidence-based IPE intervention involving first-year undergraduate students studying medicine, nursing, physiotherapy, and occupational therapy.58 Findings showed that the intervention promoted theoretical learning about teamwork. It enabled students to learn with and from each other (P < 0.001), and significantly raised awareness about collaborative practice (P < 0.05) and its link to improving the effectiveness of care delivery (P < 0.01). The qualitative data showed that IPE served to increase students’ confidence in their own professional identity and helped them to value difference, making them better prepared for clinical placement. In a longitudinal questionnaire survey from the UK, interprofessional attitudes among undergraduate students in the health professions were best molded early in their professional training, in order to minimize negative biases and perceptions.59 Furthermore, research has demonstrated that mandatory participation in IPE for pre-health professional students can result in profound changes in attitudes, interests, and professionalism.60

The IPE model case

In this IPE activity, groups of different health profession students participate in a problem-based learning case scenario. Prior to the day of the IPE exercise, students are given information on the disease featured in the case. The rationale for this is so students can focus on interprofessional interactions versus knowledge of disease. Thus, the exercise becomes process-focused rather than content-focused.

The hallmark feature of this IPE exercise is that each group of learners assumes the role of a health professional other than their own health profession role. Assigned roles are determined by a lottery draw; for example, pharmacy students, by their lottery draw, assume the role of the nurse, medical students assume the role of the pharmacist, and nurse students assume the role of the doctor. Each group interviews and examines the case patient according to the patient care perspective they are assigned. Once the analysis is complete, groups collaborate to develop plans of care. Subsequently, groups provide case presentation for the entire student audience according to the perceived perspective of the assigned role (ie, pharmacy students analyze the case through the eyes of a nurse, nursing students through a doctor’s eyes, and so on). In the end, each real health professional student group offers a critique of the lottery draw group’s analysis (ie, nursing students critique pharmacy students on how they portrayed nurses, and so on).

All identifying attributes of IPE exist in this model case. The students learn with, from, and about one another in an experiential learning process that fosters collaborative work between two or more health profession team members. This model case is a social learning experience in which the knowledge, values, insights, and skills gained through the interactions comprise the learning phenomenon. Small-group, andragogical experiences like this one uniquely enhance interprofessional learning.

The IPE contrary case

In this IPE activity, each group of health professional students (eg, medical students, nursing students, and nutrition students) interviews and examines the standardized patient according to their own health professional role, in the order in which a real life scenario might occur (ie, the nurse enters the room to get vital signs and asks the patient what brought them to the clinic today; then the physician enters with information provided to them by the nurse, and after seeing the patient the physician gives orders to the nurse which include a request for a nutrition referral. The referral ultimately occurs but there is no interactive follow-up among the three health care professionals). After the assessment is completed, each group talks about their perspective of this health care situation, with the medical students leading the group and directing how the patient’s care will flow.

Although there are more than two professions participating in this exercise, there is no evidence of collaboration or shared decision-making. All health care profession students come to the table with their own ontologic view. They learn that the physician is captain of the ship and, although they all have patient care perspectives, it is ultimately the physician who is the decision-maker. The interaction exhibits no element of teamwork since hierarchies are present.

The IPE “borderline” case

In this activity, all disciplines come together in a patient care conference to discuss a particular patient. All the disciplines share information from their perspectives, all participate in information sharing and shared decision-making. The team has decided that in the best interest of the patient, the patient would not be safe going home with her daughter since the daughter works and is not able to attend to her mother (the patient) for several hours daily. The team has collectively decided that it is best and safest if the patient goes to a rehabilitation center temporarily.

As part of the patient care conference, once the team has discussed the case thoroughly, the patient enters with her daughter to join the group. In this instance, the patient arrives and is very upset by the news the team gives her about temporary rehabilitation center placement. Each member of the team goes around the table and gives the patient the rationale for the recommendation based on their particular discipline (eg, physical therapy discusses potential for falls, nutrition discusses slow healing in relation to adequate dietary intake). Initially, the patient is in clear disagreement with the team, but ultimately is convinced that this is the best present option.

In the pseudo-application of the IPE concept, this case is termed “borderline” because it lacks a patient-centered care focus where the patient also shares in the decision-making. There were no alternatives to rehabilitation discussed in this case. Once the team decided that rehabilitation was best, they convince the patient to comply without considering any other options or addressing her perspective and obvious initial disagreement.

Challenges for IPE delivery

Challenges or barriers to IPE delivery include: hierarchies, silos, stereotypes, traditional ontologic education, communication barriers, existing curricular structures, faculty buy-in, praxis, faculty education, lack of understanding of IPE, current health care delivery structures, public perception, current scopes of practice, financing, and scheduling. One of the goals of IPE is to defuse misconceptions and stereotyping of health care professions (ie, nurses who have been portrayed on television as comical or invalid contributors to patient care; or the way the public perceives the physician as always the team leader). IPE deconstructs these types of inaccurate images and rebuilds them using correct professional identities and associated knowledge and skill sets to promote collaborative practice. Traditional education and existing curricular structures in which IPE is not integrated contribute to silo-based health care delivery structures where hierarchies exist and prohibit effective communication and collaboration.

Once IPE has been clearly defined, faculty must first be educated about the benefits of IPE so that all facilitators deliver it in the way intended. Then, financing, scheduling, and praxis (linking theory to practice) must be addressed.

Concern about current scopes of practice must also be addressed. Scopes of practice have evolved over time and will continue to do so. It is not the intention of IPE to purposefully set out to change or alter scopes of practice. IPE’s intent is to have health care professionals work in concert. Similar to a musical performance, a sort of magic happens when everyone plays in concert to generate the music. Although, each member has a specific instrument in an orchestra, they do not play alone, instead integrating with the rest of the members to make beautiful music.61 And, like an orchestra, IPE must be practiced and learned in concert with other professions.

Implications for practice and research

The extent to which different health care professionals work well together can affect the quality of the health care that they provide. While IPE has been adopted as a beneficial teaching methodology, valid research on the ultimate effects of interprofessional practice-based interventions on health care delivery and outcomes is scarce. A recent Cochrane Database updated review found six studies that reported some positive health care outcomes; however, due to the small number of studies, the heterogeneity of interventions, and the methodological limitations, the authors could not draw generalized inferences about the key elements of IPE and its effectiveness.62 More rigorous IPE studies (ie, those employing randomized clinical trials, controlled before and after studies, and interrupted time series designs with rigorous randomization procedures, better allocation concealment, larger sample sizes, and more appropriate control groups) are needed to provide better evidence of the impact of IPE on professional practice and health care outcomes.

Conclusions

This concept analysis offers insight into the attributes and characteristics of the phenomenon termed IPE. We have formulated an operational definition which may serve to eliminate some of the confusion about what IPE is, to demonstrate how IPE may be effectively promoted, and to reconcile discrepancies related to misinterpretation and ineffective delivery of the concept. IPE is an andragogical, interactive, experiential learning and socialization process. IPE occurs when two or more members of a health care team (who participate in either patient assessment and/or management) learn with, from, and about each other as they collaboratively focus on patient-centered care and achieving optimal health outcomes. In IPE, knowledge and value sharing occurs within and across disciplines. It is our hope that this concept analysis will improve overall clarity, consensus, consistency, and understanding of IPE among educators, professionals, and researchers.

In the current health care crisis and workforce shortage in the US, IPE is a particularly timely topic that addresses the problems of fragmentation in health care delivery and separation among health care professionals. IPE eliminates segmented education between health care professionals, thereby relinquishing hierarchies, misperceptions and miscommunications. IPE legitimizes a holistic approach in which health care professionals recognize one another’s contributions to patient care. It deconstructs preconceived, inaccurate stereotyping and rebuilds accurate identities and knowledge for appropriate utilization of all health care professional resources. Through effective incorporation of IPE into health professional education curricula and practice settings, optimal patient-centered outcomes can potentially result, as effective and highly integrated teams facilitate and optimize collaborative patient care and safety, although more research is needed in these areas.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Chinn PL, Kramer MK, editors. Integrated Theory and Knowledge Development in Nursing. 7th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walker LO, Avant KC. Strategies for Theory Construction in Nursing. 4th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ; Pearson/Prentiss Hall; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Daniel M, Rosenstein AH. Professional communication and team collaboration. In: Hughes RG, editor. Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses. Rockville, MD: Agency for Health care Research and Quality (US); 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosenstein AH, O’Daniel M. A survey of the impact of disruptive behaviors and communication defects on patient safety. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34:464–471. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(08)34058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sutcliffe KM, Lewton E, Rosenthal MM. Communication failures: an insidious contributor to medical mishaps. Acad Med. 2004;79:186–194. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200402000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kilner E, Sheppard LA. The role of teamwork and communication in the emergency department: a systematic review. Int Emerg Nurs. 2010;18:127–137. doi: 10.1016/j.ienj.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stewart M, Purdy J, Kennedy N, Burns A. An interprofessional approach to improving paediatric medication safety. BMC Med Educ. 2010;10:19. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-10-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary Available from: http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/educationAccessed 2009 Nov 6

- 9.Yan J, Gilbert JHV, Hoffman SJ. WHO Study Group on Interprofessional Education and Collaborative Practice. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centre for the Advancement of Interprofessional Education (CAIPE) Available from: http://www.caipe.org.uk/about-us/defning-ipe/?keywords=defnitionAccessed 2009 Aug 18

- 11.Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative (CIHC) Available from: http://www.cihc.ca/Accessed 2008 Nov 8

- 12.Interprofessional Education for Collaborative Patient-Centered Practice (IECPCP) Available from: http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hcs-sss/hhr-rhs/strateg/interprof/index-eng.phpAccessed 2008 Nov 8

- 13.Journal of Research in Interprofessional Education (JRIPE) Available from: http://www.jripe.org/index.pcp/journalAccessed 2008 Nov 8

- 14.Journal of Interprofessional Care (JIPC) Available from: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713431856~db=allAccessed 2008 Nov 8

- 15.Barr H. Competent to collaborate: Towards a competency-based model for interprofessional education. J Interprof Care. 1998;12:181–187. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mitchell L, Harvey T, Rolls L. Interprofessional standards for the care sector – history and challenges. J Interprof Care. 1998;12:157–168. [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization . Learning Together to Work Together for Health. Report of a WHO Study Group on Multiprofessional Education for Health Personnel: The Team Approach. Technical Report Series. Vol. 769. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2008. pp. 1–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yan J, Gilbert JHV, Hoffman SJ. World Health Organization study group on interprofessional education and collaborative practice. J Interprof Care. 2007;21:588–589. doi: 10.1080/13561820701775830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Institute of Medicine . Health Professions Education: A Bridge to Quality. Bethseda, MD: Institutes of Health; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Institute of Medicine . Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. City, ST: National Academics Press; 2003. Committee on Quality Health care in America and Institute of Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME) Available from: http://www.lcme.org/standard.htmlAccessed 2008 Nov 8

- 22.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Available from: http://www.acgme.orgAccessed 2008 Nov 8

- 23.National League for Nursing Accreditation Commission (NLNAC) Available from: http://www.nlnac.orgAccessed 2008 Nov 8

- 24.Commission on Collegiate Nursing Education (CCNE) Available from: http://www.aacn.nche.edu/Accreditation/pdf/resstandards08.pdfAccessed 2008 Dec 6

- 25.American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN) Available from: http://www.aacn.nche.edu/Accessed 2008 Nov 8

- 26.American Dental Education Association (ADEA) Available from: http://www.adea.orgAccessed 2008 Nov 8

- 27.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) Available from: http://www:acpe-accredit.orgAccessed 2008 Nov 8

- 28.Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) Available from: http://www.aamc.orgAccessed 2008 Nov 8

- 29.National Health Choices (NHS) Available from: http://www.nhs.ukAccessed Nov 8, 2008

- 30.Association for Prevention Teaching Research (APTR) Available from: http://www.aptrweb.org/about/index.htmlAccessed 2008 Dec 6

- 31.Olenick M, Foote E, Vanston P, et al. A regional model of interprofessional education. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2010 doi: 10.2147/AMEP.S13206. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Northeast Pennsylvania Interprofessional Education Coalition (NEPA IPEC) Available from: http://nepaipec.friendlyfrm.com/home.htmlAccessed 2008 Nov 13

- 33.Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary 2008Available from: http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/interdisciplinaryAccessed 2009 Nov 8

- 34.Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary 2008Available from: http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/multidisciplinaryAccessed 2009 Nov 8

- 35.D’Amour D, Oandasan I. Interprofessionality as the field of interprofessional practice and interprofessional education: An emerging concept. J Interprof Care. 2005;(Suppl 1):8–20. doi: 10.1080/13561820500081604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Billings DM, Halstead JA. Teaching in Nursing: A Guide for Faculty. 3rd ed. St. Louis, MO: Saunders; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hoffman SJ, Harnish D. The merit of mandatory interprofessional education for pre-health professional students. Med Teach. 2007;29:e235–e242. doi: 10.1080/01421590701551672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mackay S. The role perception questionnaire (RPQ): A tool for assessing undergraduate student’s perceptions of the role of other professions. J Interprof Care. 2008;18:289–303. doi: 10.1080/13561820410001731331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parsell G, Bligh J. The development of a questionnaire to assess the readiness of health care students for interprofessional learning (RIPLS) Med Educ. 1999;33:95–100. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.1999.00298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mattick K, Bligh J. An e-resource to coordinate research activity with the readiness for interprofessional learning scale (RIPLS) J Interprof Care. 2005;19:604–613. doi: 10.1080/13561820500389130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McFadyen AK, Webster V, Strachan K, Figgins E, Brown H, McKechnie J. The readiness for interprofessional learning scale: A possible more stable sub-scale model for the original version of RIPLS. J Interprof Care. 2005;19:595–603. doi: 10.1080/13561820500430157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McFadyen AK, Webster VS, Maclaren WM. The test-retest reliability of a revised version of the readiness for interprofessional learning scale (RIPLS) J Interprof Care. 2006;20:633–639. doi: 10.1080/13561820600991181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McFadyen AK, Madlaren WM, Webster VS. The interdisciplinary education perception scale (IEPS): An alternative remodeled sub-scale structure and its reliability. J Interprof Care. 2007;21:433–443. doi: 10.1080/13561820701352531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lindqvist S, Duncan A, Shepstone L, Watts F, Pearce S. Case-based learning in cross professional groups – the development of a prerequisite interprofessional learning program. J Interprof Care. 2005;19:509–520. doi: 10.1080/13561820500126854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lidskog M, Lofmark A, Ahlstrom G. Interprofessional education on a training ward for older people: Students’ conceptions of nurses, occupational therapists and social workers. J Interprof Care. 2007;21:387–399. doi: 10.1080/13561820701349420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Muller JH, Jain S, Loeser H, Irby DM. Lessons learned about integrating a medical school curriculum: perceptions of students, faculty and curriculum leaders. Med Educ. 2008;42:778–785. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Curran VR, Sharpe D, Forristall J, Flynn K. Student satisfaction and perceptions of small group process in case-based interprofessional learning. Med Teach. 2008;30:431–433. doi: 10.1080/01421590802047323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goodwin HJ, Stein D. Deliberative discussion as an innovative teaching strategy. J Nurs Educ. 2008;47:272–274. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20080601-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Duffy A. Guided reflection: a discussion of the essential components. Br J Nurs. 2008;17:334–339. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2008.17.5.28832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chakraborti C, Boonyasai RT, Wright SM, Kern DE. A systematic review of teamwork training interventions in medical student and resident education. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:846–853. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0600-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Curran VR, Sharpe D, Forristall J, Flynn K. Student satisfaction and perceptions of small group process in case-based interprofessional learning. Med Teach. 2008;30:431–433. doi: 10.1080/01421590802047323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Furze J, Lohman H, Mu K. Impact of an interprofessional community-based educational experience on students’ perceptions of other health professions and older adults. J Allied Health. 2008;37:71–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Goelen G, de Clercq G, Huyghens L, Kerckhofs E. Measuring the effect of interprofessional problem-based learning on the attitudes of undergraduate health care students. Med Educ. 2006;40:555–561. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hallin K, Kiessling A, Waldner A, Henriksson P. Active interprofessional education in a patient based setting increases perceived collaborative and professional competence. Med Teach. 2009;31:151–157. doi: 10.1080/01421590802216258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hammick M, Freeth D, Koppel I, Reeves S, Barr H. A best evidence systematic review of interprofessional education: BEME Guide no. 9. Med Teach. 2007;29:735–751. doi: 10.1080/01421590701682576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Johnson AW, Potthoff SJ, Carranza L, Swenson HM, Platt CR, Rathbun JR. CLARION: a novel interprofessional approach to health care education. Acad Med. 2006;81:252–256. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200603000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hoffman SJ, Rosenfield D, Gilbert JH, Oandasan IF. Student leadership in interprofessional education: benefits, challenges and implications for educators, researchers and policymakers. Med Educ. 2008;42:654–661. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cooper H, Spencer-Dawe E, McLean E. Beginning the process of teamwork: design, implementation and evaluation of an inter-professional education intervention for first year undergraduate students. J Interprof Care. 2005;19:492–508. doi: 10.1080/13561820500215160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Coster S, Norman I, Murrells T, et al. Interprofessional attitudes amongst undergraduate students in the health professions: A longitudinal questionnaire survey. Internat J Nurs Stud. 2008;45:1667–1681. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hoffman SJ, Harnish D. The merit of mandatory interprofessional education for pre-health professional students. Med Teach. 2007;29:e235–e242. doi: 10.1080/01421590701551672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Briggs MH. Systems for collaboration. Integrating multiple perspectives. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 1999;8:365–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Reeves W, Zwarenstein M, Goldman J, et al. Interprofessional education: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;4:1–22. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002213.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]