Abstract

Objectives/Hypothesis

Develop a standardized letter of recommendation (SLOR) for otolaryngology residency application that investigates the qualities desired in residents and letter writer’s experience. Compare this SLOR to narrative letters of recommendation (NLOR).

Study Design

Prospective SLOR/NLOR Comparison.

Methods

The SLOR was sent to a NLOR writer for each applicant. The applicant’s NLOR/SLOR pair was blinded and ranked in seven categories by three reviewers. Inter-rater reliability and NLOR/SLOR rankings were compared. Means of cumulative NLOR and SLOR scores were compared to our departmental rank list.

Results

Thirty-one SLORs (66%) were collected. The SLORs had higher inter-rater reliability for applicant’s qualifications for otolaryngology, global assessment, summary statement, and overall letter ranking. Writer’s background, comparison to contemporaries/predecessors, and letter review ease had higher inter-rater reliability on the NLORs.

Mean SLOR rankings were higher for writer’s background (p=0.0007), comparison of applicant to contemporaries/predecessors (p=0.0031), and letter review ease (p<0.0001).

Mean SLOR writing time was 4.17±2.18 minutes. Mean ranking time was significantly lower (p<0.0001) for the SLORs (39.24±23.45 seconds) compared to the NLORs (70.95±40.14 seconds).

Means of cumulative SLOR scores correlated with our rank list (p=0.004), whereas means of cumulative NLOR scores did not (p=0.18). Means of cumulative NLOR and SLOR scores did not correlate (p=0.26).

Conclusions

SLORs require little writing time, save reviewing time, and are easier to review compared to NLORs. Our SLOR had higher inter-rater reliability in 4 of 7 categories and was correlated with our rank list. This tool conveys standardized information in an efficient manner.

Keywords: Otolaryngology, Residency Selection, Letters of Recommendation

INTRODUCTION

An important component to residency application is the applicant’s narrative letter of recommendation (NLOR). Typically, applicants have 3-4 letters from various faculty members who supervised or worked with that particular applicant during medical school. Usually, NLORs in otolaryngology contain three elements.1 First, the relationship between the letter writer and the applicant is stated. Second, the writer gives a brief summary about the applicant’s academic or clinical record. Third, the applicant’s personality traits and previous performance are compared to those of his or her peers.1 Although NLORs are considered to be an important part of the residency application process, they often contain information that is ambiguous. Many studies have demonstrated flaws inherent within the traditional NLOR: they do not predict future clinical performance,2,3 show only fair, at best, agreement when evaluated by different individuals,4 and contain significant gender bias.1 In our previous publication, we attempted to identify methods that could improve NLORs in otolaryngology.5

In order to improve upon the issues found in NLORs, in 1995 the Council of Emergency Medicine Residency Directors created a standardized letter of recommendation form (SLOR).6,7 This emergency medicine SLOR has been shown to require less evaluation time and have better inter-rater reliability compared to NLORs.8 Girzadas et al. also indentified predictors that might help a medical student receive a guaranteed match recommendation by the SLOR writer.9 In emergency medicine, the SLOR offers an alternative to NLORs that may help improve resident selection.

Information about how to properly complete the emergency medicine SLOR is available online for SLOR writers.7 Writers are instructed that the SLOR should be standardized, concise, and discriminating.7 Faculty with experience in resident selection, such as residency program directors and medical school clerkship directors, are encouraged to write a “group” SLOR.7 Additionally, the SLOR’s writer is asked to review the SLORs authored in the previous year so that he or she may provide accurate information for the different sections of the SLOR.7 Finally, the clerkship secretaries are asked to pull clerkship grades for the student so the grades reported in the SLOR are correct.7

The recent otolaryngology literature contains multiple publications which are primarily focused on the flaws in the current methodology used to select residents.1,5,10-14 Messner and Shimahara reviewed NLORs for otolaryngology residency applicants and found significant gender bias in the ways that male and female letter writers described applicants and concluded their paper by proposing the use of an SLOR in otolaryngology residency selection.1 In 2012, our group published a study that used SLOR methodology in the cohort of applicants to our pediatric otolaryngology fellowship.10 The SLOR contained five content-based categories: the letter writer’s background, comparison of the applicant to his or her contemporaries and predecessors, qualifications for otolaryngology, global assessment, and a summary statement. These five content-based categories allowed for a more objective, standardized method to evaluate the applicant in terms of the depth of the letter writer’s understanding of the applicant, concrete examples of the applicant’s personal traits (e.g. language, reasoning, compassion, ethics, and surgical skills), and numeric comparison of the applicant to his or her peer group. The fellowship SLORs demonstrated better inter-rater reliability in 6 of 7 categories with less interpretation time than NLORs. Pediatric otolaryngologists also found the fellowship SLOR easier to review than traditional NLORs.10 Our SLOR may represent a potential improvement upon traditional NLORs for pediatric otolaryngology fellowship selection. Our pediatric program used SLORs during the review process for this year’s application cycle and will be continue to use SLORs in the future.

The present manuscript replicates our previous fellowship SLOR study in the pilot use of an SLOR for the resident applicant pool to the otolaryngology residency program at the University of Colorado during the 2011-2012 application year.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design

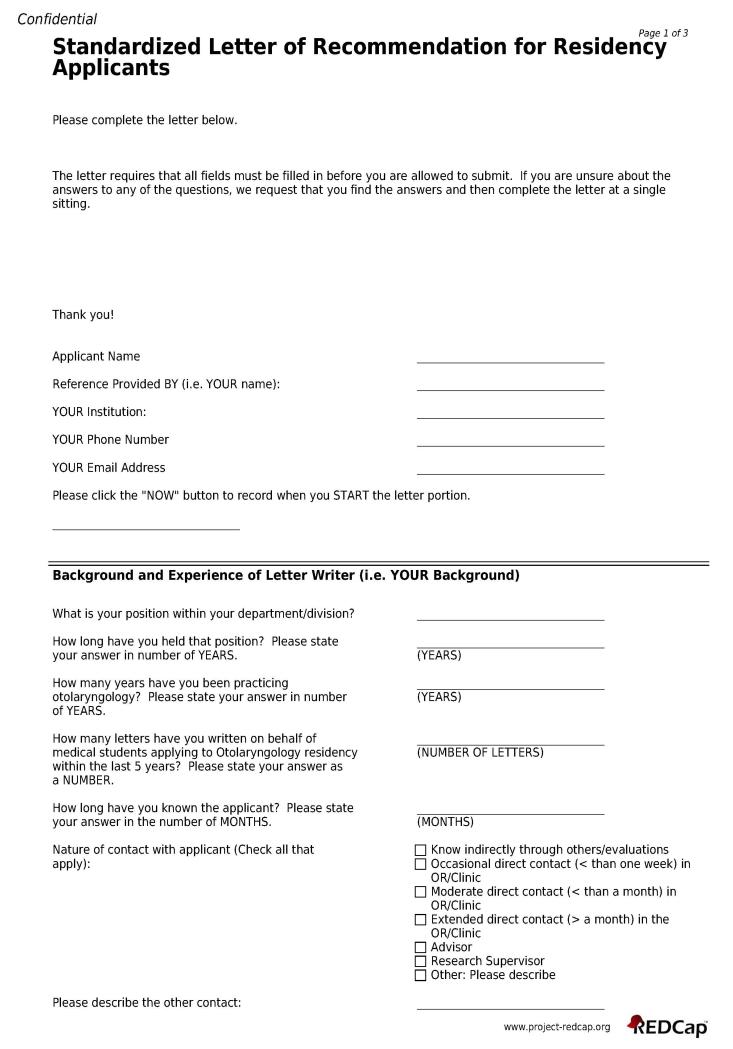

A resident SLOR, based on our previous fellowship SLOR,10 was developed in a format requiring objective answers from the writer (Figure 1). This letter is divided into five content-based categories: writer’s background, a comparison of the applicant to his or her contemporaries and predecessors, qualifications of the applicant for otolaryngology residency, a global assessment that asks the SLOR writer where the applicant ranks compared to all previous applicants the writer has recommended, and a summary statement category where the SLOR writer may provide a brief narrative response as well as an overall rating of the applicant.

Figure 1.

Otolaryngology residency SLOR form pages 1-3.

SLOR writers were chosen from all of the NLOR writers for the 2011-2012 residency applicants who had been offered interviews at the University of Colorado. One of the applicant’s NLOR writers was asked to complete the SLOR with a goal of creating an SLOR/NLOR pair for each applicant. Mirroring the effort by the Council of Emergency Medicine Residency Directors, writers most familiar with the evaluation of medical students or residents were selected.7 First, we tried to identify the applicant’s medical school rotation coordinator via the applicant’s respective otolaryngology department website. If the applicant did not have a medical school rotation coordinator specified, then the residency program director was selected. In cases where the applicant was from a medical school without an otolaryngology residency program, the otolaryngologist with the longest tenure, who had also written a NLOR for the applicant, was selected. Approval by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board (#11-1145) for this research project was obtained.

The SLOR was distributed using REDCap Survey database hosted at the University of Colorado School of Public Health. REDCap, or Research Electronic Data Capture, is a HIPAA-compliant, secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for different types of research studies.15

Completed SLORs were paired with the same author’s NLOR and both letters were blinded of all identifying information, removing all references to names and institutions that might identify the applicant or SLOR/NLOR writer. Three reviewers with previous experience on the residency ranking committee were selected: a senior level faculty member with more than 10 years experience in residency selection, a junior level faculty member with less than 10 years experience in residency selection, and a chief resident with 1 year experience in residency selection. All of the reviewers were physicians who were not involved in the residency selection process for the 2011-2012 application cycle. These SLORs were not used in the selection process. Prior to ranking the letters, a member of the research team reviewed the ranking scales with each of the three reviewers.

The NLOR and SLOR pairs were evaluated on a Likert-type scale examining five content-based categories as well as an overall ranking of the each respective letter and an ease of review ranking (i.e. how easy was the letter to review compared to letters that the reviewer had read in the past). NLORs were evaluated based on the content in the letter (Table I). For instance, a NLOR could receive a “0” for comparison to contemporaries/predecessors if it did not contain information that compared the applicant to other medical students. The SLOR ranking scale was based on the applicant’s likelihood to match using the information found in each section of the letter (Table I). The reviewers determined the overall rankings for the NLORs and SLORs by assessing the whole content of each respective letter. The ease of review ranking scale was the same for both letter types and asked the reviewer how easy the letter was to assess in comparison to previous letters reviewed (Table I). The reviewers also recorded the length of time needed to review and rank each letter. The ranking scales were adapted from our previous study10 and a study that compared SLORs to NLORs for emergency medicine resident applicants.8

Table I.

Criteria used to rank the NLORs and SLORs for the five content-based categories and ease of review.

| NLOR Score Classification | SLOR Score Classification | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Five Content-Based Categories and Overall Ranking | 7 | Includes glowing statements such as “is one of the finest students to come from our school,” “is one of the best students I have ever worked with,” “richly deserves the honors awarded in the rotation,” or “receives my highest recommendation. |

Guaranteed match. |

|

| |||

| 6 | May include some honors grades, top 15-20%, near honors | Outstanding or very likely to match. | |

|

| |||

| 5 | Contains the obligatory “good fund of knowledge,” “punctual,” “hardworking,” “progressed well,” “should be an excellent candidate for fellowship training,” along with some superlatives. |

Excellent. | |

|

| |||

| 4 | Contains mildly complimentary but non-committal language. Pleasantly describes an average resident and tries to put a good spin on the description. |

Very good. | |

|

| |||

| 3 | May be completely neutral as if the writer has never met the resident, or have some subtle descriptions of the student’s averageness or contains slightly negative comments. |

Good. | |

|

| |||

| 2 | Contains troublesome or negative comments with little or no balancing superlatives. Almost guarantees “no interview.” |

Would not rank. | |

|

| |||

| 1 | Is hard to come by as most students do not ask someone who dislikes them or who has been disappointed in their performance to write them a letter of recommendation. All by itself guarantees “no interview.” |

Would not rank, negative comment. |

|

|

| |||

| 0 | Not in Letter | Not Applicable | |

|

| |||

| Ease of Review Category | 7 | Minimal time required to review letter, writer’s comments addressed the areas of interest for the applicant in with concrete examples. |

|

|

| |||

| 6 | Significantly less than average amount of time needed to interpret letter. Author could have been more concise in some places. |

||

|

| |||

| 5 | Less than average amount of time needed to interpret letter. | ||

|

| |||

| 4 | Average amount of time needed to review letter. | ||

|

| |||

| 3 | More than average amount of time needed to interpret letter. | ||

|

| |||

| 2 | Significantly more than average amount of time needed to interpret letter. Author failed to use concise examples. |

||

|

| |||

| 1 | Extensive amount of time needed to interpret letter. Author’s comments about applicant were difficult to understand. |

||

Statistical Analysis

SLOR results were characterized using descriptive statistics. For the four comparison to contemporaries/predecessors questions about the number of medical students receiving honors, high pass, pass, or fail grades, only complete reports were used (i.e. data was excluded if the writer’s numbers did not make sense or were all zero). The total number of students who had completed an otolaryngology rotation was summed and then the mean percentage of students receiving each grade (honors, high pass, pass, or fail) was calculated.

Kendall’s coefficient of concordance (Kendall’s W) was used to calculate the agreement among raters on the rankings for each component of both the SLORs and the NLORs. Kendall’s W is a non-parametric statistic and makes no assumptions regarding the nature of the probability distribution. The degree of agreement for Kendall’s W is defined as: ≤0 poor, 0-0.2 slight, 0.2-0.4 fair, 0.4-0.6 moderate, 0.6-0.8 substantial, and 0.8-1.0 almost perfect.16 This was accomplished using MAGREE macro V1.0 in SAS that requires all applicants to be rated by all of the otolaryngologists.17,18

Paired t-tests were used to compare the mean ranks on each category between SLORs and NLORs and length of time to complete the ranking of the letters. The mean cumulative scores for each NLOR and SLOR were found by summing and then averaging each reviewer’s scores for the writer’s background, comparison of the applicant to contemporaries/predecessors, qualifications for otolaryngology, global assessment, summary statement, and overall ranking categories. Ease of review was not included during the calculation of the cumulative SLOR or NLOR scores. For applicants who were subsequently interviewed at and ranked by the University of Colorado, a linear regression analysis was performed that compared that resident’s rank list position to their mean cumulative SLOR and NLOR rankings, respectively. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical comparisons were performed in SAS® 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

In 2011, 47 applicants were offered interviews to the University of Colorado Otolaryngology Residency Program, for whom 31 SLORs were obtained (66% response rate). The mean time to write the SLOR was 4.17 ± 2.18 minutes. The SLOR results are presented in Table II. Two SLOR responses were not included in the calculation of the mean percentage of medical students receiving a particular grade (honors, high pass, pass, or fail) on their otolaryngology rotation because the answers provided by the respondents did not make sense (i.e. ‘9999’ or ‘0’) in each of the four categories.

Table II.

SLOR results.*

| Background | Outcome |

|---|---|

| Writer’s Departmental Position, N (%): | |

| Residency Program Director | 14 |

| Senior Faculty, including Chair | 13 |

| Junior Faculty | 4 |

| Mean years in position, (SD) | 6.53 (7.02) |

| Mean years practicing otolaryngology, (SD) | 13.71 (9.46) |

| Mean number of NLORs written in last 5 years, (SD) | 18.68 (13.33) |

| Mean length of contact with applicant, months, (SD) | 19.77 (11.50) |

| Contact with Applicant: | |

| Known indirectly through others/evaluations | 6 |

| Occasional direct contact (< than one week) in OR/Clinic | 5 |

| Moderate direct contact (< than a month) in OR/Clinic | 11 |

| Extended direct contact (> than a month) in OR/Clinic | 14 |

| Advisor | 13 |

| Research Supervisor | 14 |

| Comparison to Contemporaries/Predecessors | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Honors | High Pass | Pass | Fail | |

| Candidate’s grade, if given | 28 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Mean Percentage of Residents’ Grades, (SD)* | 52.5 (23.6) | 28.9 (12.9) | 17.9 (20.7) | 0.65 (1.4) |

| Qualifications for Otolaryngology | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outstanding | Excellent | Good | Meets Expectations | |

| Commitment to Otolaryngology | 26 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Work ethic | 26 | 4 | 1 | 0 |

| Ability to develop a treatment plan | 17 | 12 | 2 | 0 |

| Surgical skills | 22 | 6 | 3 | 0 |

| Ability to interact with others | 23 | 4 | 4 | 0 |

| Ability to communicate to patients | 17 | 13 | 1 | 0 |

| Almost none | < Average | Average | > Average | |

| Guidance needed during residency | 12 | 15 | 4 | 0 |

| Outstanding | > Average | Average | < Average | |

| Prediction of success during residency | 22 | 8 | 1 | 0 |

| Timeliness of paperwork completion | 23 | 7 | 1 | 0 |

| Global Assessment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outstanding | Excellent | Good | Meets Expectations | |

| Compared to other applicants, how is this applicant ranked? |

18 | 12 | 1 | 0 |

| Very competitive | Competitive | Possible match | Unlikely match | |

| How highly would the applicant reside on your match list? |

18 | 10 | 3 | 0 |

| Summary Statement | |

|---|---|

| Suitability for position as an otolaryngology resident: | |

| Recommend highly without reservation | 27 |

| Recommend without reservations | 4 |

| Recommend with reservations | 0 |

| Do not recommend | 0 |

| Mean time in minutes to complete the form, (SD) | 4.17 (2.18) |

Note: Two respondents were excluded because of they did not know the otolaryngology rotation grade distribution and failed to provide analyzable data.

Three reviewers ranked each NLOR/SLOR pair for the 31applicants. Inter-rater reliability was higher on the SLORs for qualifications for otolaryngology, global assessment, summary statement, and overall ranking. For writer’s background, comparison to contemporaries/predecessors, and ease of review, the NLORs had higher inter-rater reliability. The values of Kendall’s W on the SLORs ranged from W = 0.37-0.87 which represents fair to almost perfect agreement and W = 0.49-0.74 for the NLORs, which represents moderate to substantial agreement (Table III). On both the SLORs and NLORs there was only fair to moderate agreement about the ease of ranking review.

Table III.

Kendall’s W for the SLORs and NLORs showing the inter-rater reliability for each section ranked by the reviewers.

| SLOR | NLOR | |

|---|---|---|

| Background | 0.45 | 0.62 |

| Comparison to Contemporaries/Predecessors | 0.54 | 0.64 |

| Qualifications for Otolaryngology | 0.84 | 0.49 |

| Global Assessment | 0.87 | 0.74 |

| Summary Statement | 0.72 | 0.62 |

| Overall Ranking | 0.78 | 0.67 |

| Ease of Ranking Review | 0.37 | 0.49 |

Note. ≤ 0 Poor, 0 - 0.2 Slight, 0.2 - 0.4 Fair, 0.4 - 0.6 Moderate, 0.6 - 0.8 Substantial, 0.8 – 1.0 Almost perfect.

By paired t-test the average time to compete the ranking of the letters of recommendation was significantly lower for the SLORs, 39.24 ± 23.45 seconds, compared to 70.95 ± 40.14 seconds for the NLORs (p < 0.0001).

Mean rankings for the SLORs and NLORs are shown in Table IV. These mean rankings were statistically higher on the SLORs compared to NLORs on the following categories: writer’s background, comparison of the applicant to contemporaries and predecessors, and the ease of letter review. No statistical difference was found between the other categories (Table IV).

Table IV.

Mean and standard deviations for the SLORs and the NLORs. P-values from paired t-tests are shown.

| SLOR | NLOR | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Background | 5.5 ± 1.1 | 4.7 ± 2.0 | 0.0007 |

| Comparison to Contemporaries/Predecessors | 5.3 ± 1.1 | 4.5 ± 2.2 | 0.003 |

| Qualifications for Otolaryngology | 5.4 ± 1.1 | 5.3 ± 1.4 | 0.58 |

| Global Assessment | 5.4 ± 1.3 | 5.6 ± 0.85 | 0.28 |

| Summary Statement | 5.9 ± 1.0 | 5.7 ± 0.92 | 0.14 |

| Overall Ranking | 5.4 ± 1.0 | 5.5 ± 0.90 | 0.50 |

| Ease of Ranking Review | 5.7 ± 0.81 | 4.6 ± 1.3 | < 0.0001 |

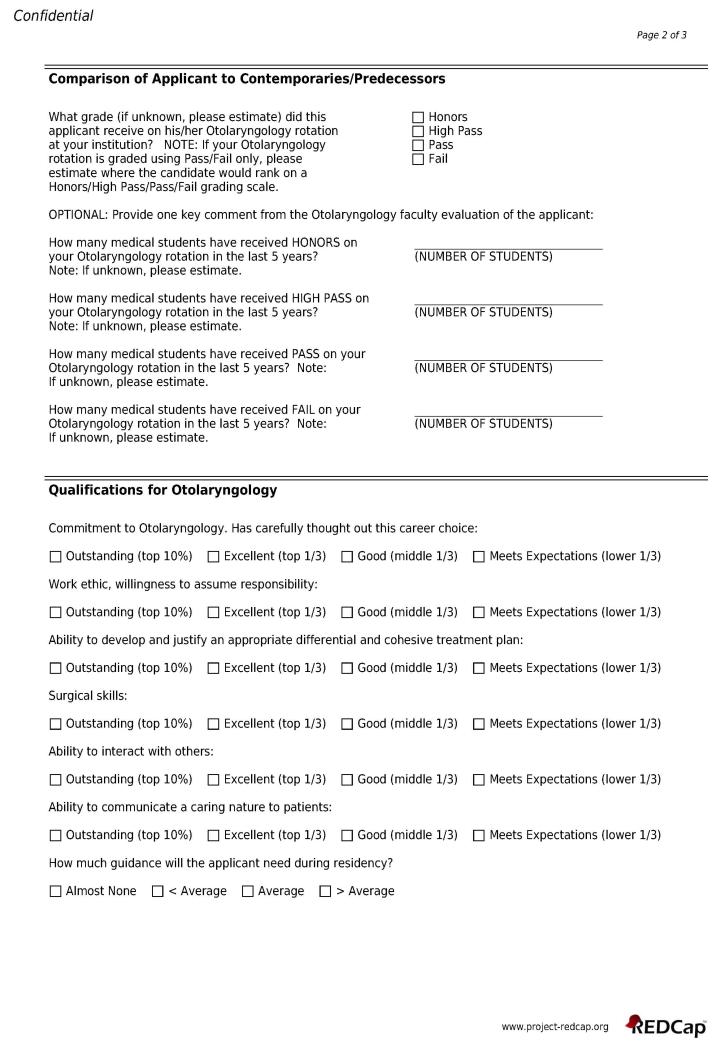

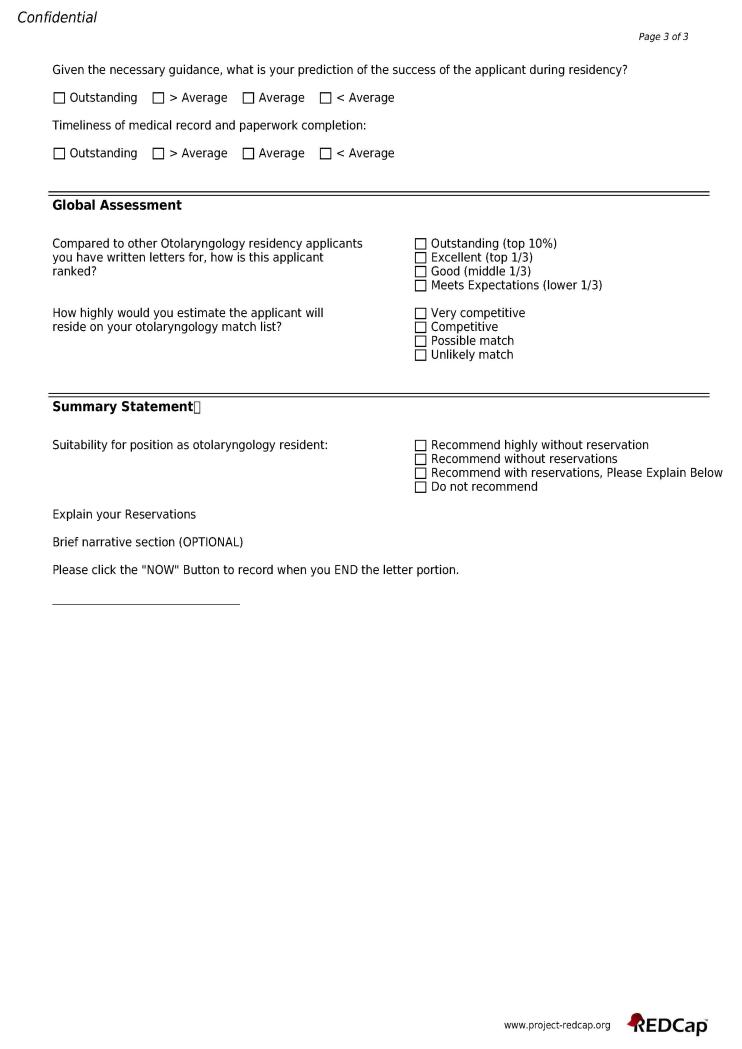

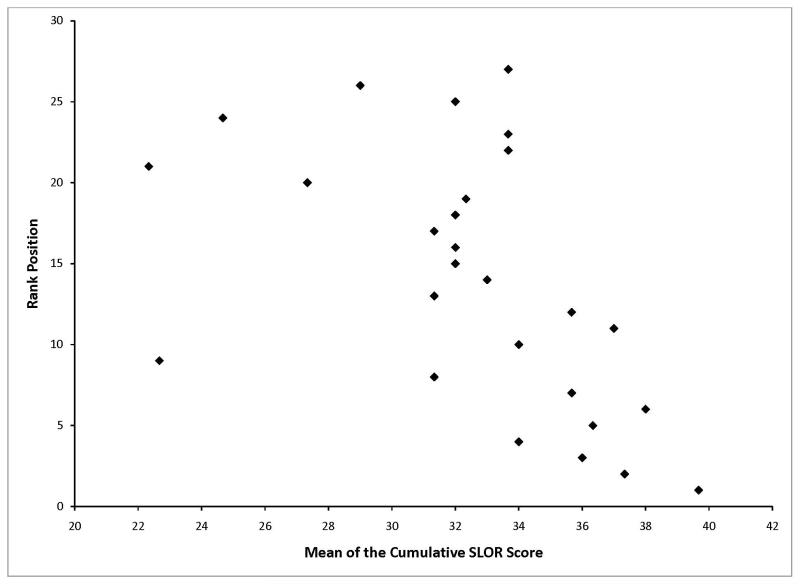

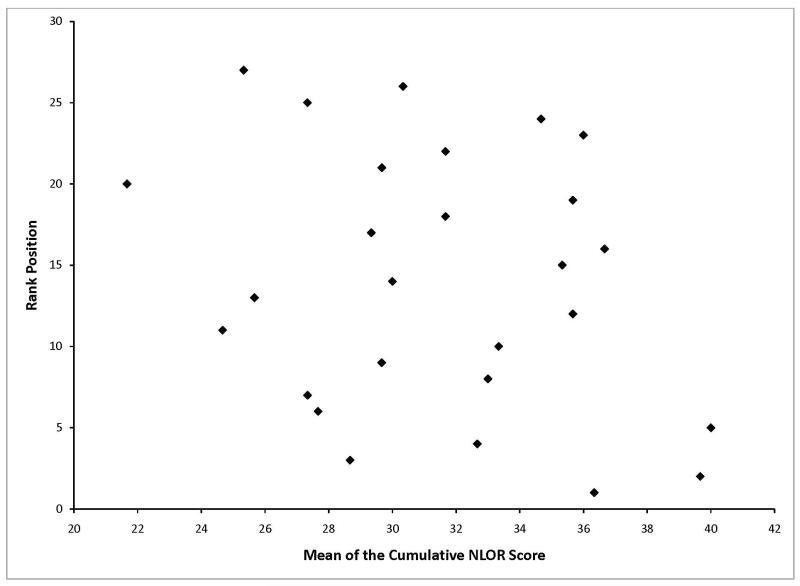

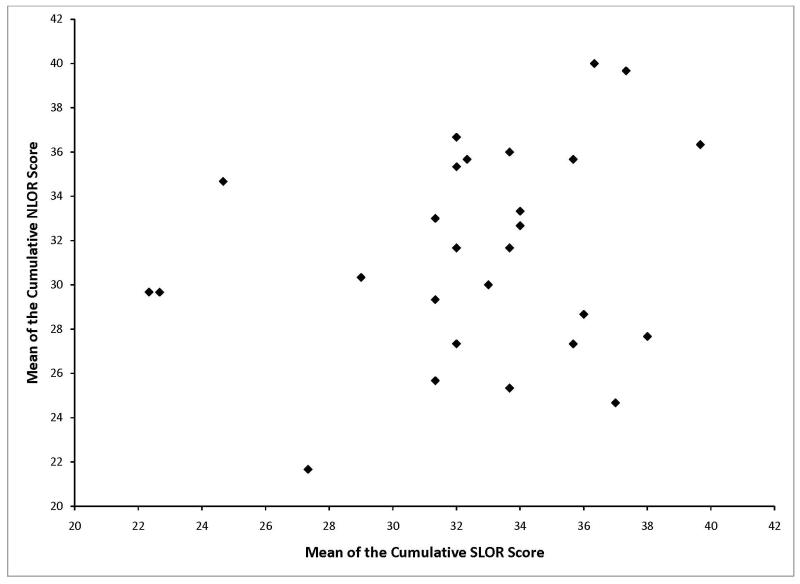

Twenty-seven of the 31 applicants were ranked by the University of Colorado residency ranking committee. Lower numbers corresponded to applicants who were ranked higher on our rank list (i.e. 1=highest and 27=lowest). Higher mean cumulative SLOR or NLOR scores corresponded to a more highly ranked letter (i.e. 42=highest possible score and 7=lowest possible score). There was a moderate negative correlation between the rank position of the applicants and the mean of the cumulative SLOR scores, r = −0.53, p = 0.004 (Figure 2). There was no correlation between the rank position of the applicants and the mean of the cumulative NLOR scores, r = −0.27, p = 0.18 (Figure 3). There was no correlation between the mean of the cumulative SLOR and NLOR scores (r = 0.23, p = 0.26) (Figure 4).

Figure 2.

Scatterplot of the rank position compared to the mean of the cumulative SLOR scores. Lower rank list position corresponds to higher quality applicants as determined by our selection committee. Higher mean cumulative SLOR scores corresponds to higher quality SLORs as determined by three letter reviewers.

Figure 3.

Scatterplot of the rank position compared to the mean of the cumulative NLOR scores. Lower rank list position corresponds to higher quality applicants as determined by our selection committee. Higher mean cumulative NLOR scores corresponds to higher quality NLORs as determined by three letter reviewers.

Figure 4.

Scatterplot comparing the mean of the cumulative SLOR scores to the mean of the cumulative NLOR scores.

DISCUSSION

In 2012, there were 390 applicants for 285 otolaryngology residency positions in the National Resident Match.19 With approximately 1.4 applicants per position, it is vital for residency programs to continually evaluate their selection methods. Recent literature has shown that the factors (i.e. rank list position, clerkship grades, and standardized exam scores) used in resident selection in otolaryngology and other fields may be of dubious value and may not predict future clinical performance.12,20,21 Bent et al. reviewed the performance of eight consecutive residency classes and found that resident performance, as assessed by faculty evaluation, peer-resident evaluation, selection for chief resident, and receipt of an annual graduating resident teaching award, did not correlate with either the applicant’s rank number or resident’s grouping on the rank list, which was grouped into halves, thirds, or quartiles.12 A high variability in medical school clerkship grading systems exists, both between different institutions and within a single institution, which makes it difficult for residency programs to evaluate applicants on their clerkship grades.20 In their study evaluating information collected by the National Resident Matching Program, Borowitz et al. demonstrated that medical school grades, standardized exam scores, interviews conducted during the application process, and rank list position do not predict a pediatric resident’s clinical performance.21

NLORs are considered an essential part of the residency selection process.2 Compared to otolaryngology residency applicants, program directors view NLORs as being significantly more important in the selection process.13 NLORs have been shown to contain primarily positive feedback about an applicant.1 Female applicant appearance is more likely to be described by male letter writers, who make up the majority of NLOR writers.1 There has been evidence throughout the literature that NLORs are not predictive of future residency performance.2,3 In their large survey of internists, DeZee et al. reported that NLORs were felt to be unable to discern future performance in residency or medical school.2 NLORs do not predict future radiology residency performance, as assessed by rotation evaluations, retrospective faculty recall scores, and board examination scores.3 Additionally, NLORs do not communicate consistent information to letter readers. Dirschl and Adams found only slight to fair inter-rater reliability when they asked six orthopedic faculty to review and rank NLORs for orthopedic residency applicants as either “outstanding,” “average,” or “poor.”4 Most of the tools used to evaluate residency applicants have been shown to be non-predictive of clinical performance.

This study applied a tool, the SLOR, which may improve the ability for programs to evaluate applicants. Emergency medicine residency programs introduced SLORs in the mid-1990s.6,7 Recent publications called into question the accuracy of the global assessment score22 and potential gender bias in the likelihood to match question.23 However, the emergency medicine SLOR requires less evaluation time, has improved inter-rater reliability over NLORs, and presents standardized, less subjective information to residency selection committees.8,9

Our previous study demonstrated improved inter-rater reliability and less evaluation time in pediatric fellowship selection.10 In the present inquiry, we demonstrated that SLORs have higher inter-rater reliability for qualifications for otolaryngology, global assessment, summary statement, and overall letter ranking. NLORs, on the other hand, had higher inter-rater reliability on the writer background, comparison to contemporaries/predecessors, and ease of letter review sections. This differs from the results we had in our fellowship SLOR study in which the SLOR had higher inter-rater reliability on every section except for ease of letter review.10 It is interesting to note that the only sections where the NLORs had higher inter-rater reliability compared to the SLORs were also the only sections where the mean rankings between the NLOR/SLOR pairs were statistically different and higher on the SLORs (Table IV). One possible reason for the statistically significant differences between mean ranks of the writer’s background and the comparison to contemporaries/predecessor sections could be the fact that our SLOR (Figure 1) requires this information to be entered by the letter writer, while the NLOR format does not require this information. This information is more consistently absent or less detailed within the NLORs, as reflected by higher inter-rater reliability and lower mean rankings for the NLORs. The significant difference found between the NLORs and SLORs on the ease of review section may be attributed to the fact that SLORs are easier to review than NLORs though there was less agreement among raters about how much easier. The mean rankings for both the SLORs and NLORs indicate that both letter formats typically advocate in favor of the applicant.

The means of the cumulative NLOR and SLOR scores do not correlate suggesting that these letters may contain varied information and/or convey information differently (Figure 4). This is an interesting finding in light of the fact that the SLOR and NLOR were written by the same writer. An additional notable finding was that the means of the cumulative SLOR scores correlated with our institution’s rank list, whereas the means of the cumulative NLOR scores did not. This was not demonstrated in our fellowship SLOR study.10 This correlation may indicate that information contained within the SLOR is similar to that which is used to create a rank list at our institution while the NLOR may not contain this information. However, if our rank list for residency selection is as non-predictive of residents’ clinical performance as other studies have shown,12,21 an instrument such as the SLOR that correlates with that rank list may also be of dubious value. Our finding that SLORs have a short composition time (<5 minutes) and require significantly less time to review (39.24 ± 23.45 seconds, compared to 70.95 ± 40.14 seconds) provides additional support for the possible use of SLORs in otolaryngology residency selection. For example, by replacing one NLOR with an SLOR, the ~30 second time savings per letter results in a 25 minutes reduction in total time spent reading letters for a residency ranking committee member reviewing the letters for 50 applicants. Although this is a small amount of time saving per letter reader, it does support the idea that SLORs may enhance the efficiency of the residency selection process.

There are a number of limitations to this study. A few of the SLOR questions may ask questions that the writer may not be able to answer accurately as indicated in Table II. For example, the SLOR asks the writer to report the applicant’s grade on a defined scale (Honors, High Pass, Pass, Fail) even if he or she does not use that scale at their institution. Also, briefing the letter reviewers about the study’s ranking scales may have influenced the scores that they gave to the NLORs and SLORs, respectively. The NLORs and SLORs were presented in pairs for each applicant, with the NLOR always being presented first. This may have influenced the shorter mean reviewing time for the SLORs. Although the reviewers were separate from the residency selection process for the 2011-2012 application cycle, at the time of the study they were all part of the University of Colorado Department of Otolaryngology and may have prior knowledge about the aims of our study. This could have influenced the manner in which the NLORs and SLORs were ranked by each reviewer.

Otolaryngology is a highly competitive field that is relatively small compared to other fields in medicine and surgery. This competitiveness results in a high quality applicant pool that may be difficult to separate, as shown by the high mean ranks found on both the NLORs and SLORs (Table IV) and the high rankings given out to applicants by SLOR writers (Table II). Additionally, letter writers tend to advocate for the person they are writing on behalf of, which makes applicant pool separation more challenging. Furthermore, the population included in this study is limited to the applicants that have been invited for an interview and thus do not represent the overall applicant pool to our residency program. Since NLORs are typically used by most programs to screen the applicant pool for those to be invited for interview, our pre-selected study population may contain a disproportionally larger proportion of high quality applicants. This makes us unable to comment on the use of SLORs as a screening tool. In addition, this selection bias makes separating the abilities of SLORs and NLORs more challenging in this study. Conducting a multi-institutional rating study prior to selection for interview could test the external validity of otolaryngology residency SLORs in the residency selection process. This type of multi-institutional study would also allow for testing the SLOR in a much larger pool of residency applicants instead of the small pool of applicants already selected for interviews at our program.

Another limitation of the SLOR is that program directors may be reluctant to implement this tool. Because of their responsibilities to the medical students of their own school, program directors who have written NLORs for applicants may be reluctant to fill out SLORs out of the concern that it may adversely affect a less-than-ideal applicant from their own school.

CONCLUSIONS

This study demonstrates that SLORs may complement NLORs for otolaryngology residency selection. In contrast to NLORs, our SLOR demonstrated better inter-rater reliability on the majority of content-based categories with less interpretation time. Additionally, otolaryngologists rate SLORs as easier to review when compared to NLORs. Also, mean rankings for SLOR/NLOR pairs, written by the same author, do not correlate suggesting that these tools work differently in the hands of letter readers. While SLORs may not replace traditional NLORs, it is important for physicians to gain familiarity with standardized letters and to consider how these tools may augment the otolaryngology resident selection process by efficiently conveying standardized information in a reliable fashion. These tasks are particularly relevant in light of the ever-increasing pressure on training programs to select and train excellent physicians in a set amount of time with a fixed amount of resources.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Kenny H. Chan, M.D., Julie A. Goddard, M.D., and Pamela A. Mudd, M.D. for rating the standardized and narrative letters of recommendation.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The data collection program, REDCap, utilized in this publication was supported by NIH/NCRR Colorado CTSI Grant Number UL1 RR025780. Its contents are the authors’ sole responsibility and do not necessarily represent official NIH views.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST: None

REFERENCES

- 1.Messner AH, Shimahara E. Letters of recommendation to an otolaryngology/head and neck surgery residency program: their function and the role of gender. Laryngoscope. 2008;118(8):1335–1344. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e318175337e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeZee KJ, Thomas MR, Mintz M, Durning SJ. Letters of recommendation: rating, writing, and reading by clerkship directors of internal medicine. Teach Learn Med. 2009;21(2):153–8. doi: 10.1080/10401330902791347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyse TD, Patterson SK, Cohan RH, et al. Does medical school performance predict radiology resident performance? Acad Radiol. 2002;9(4):437–45. doi: 10.1016/s1076-6332(03)80189-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dirschl DR, Adams GL. Reliability in evaluating letters of recommendation. Acad Med. 2000;75(10):1029. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200010000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prager JD, Myer CM, 3rd, Pensak ML. Improving the letter of recommendation. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;143(3):327–330. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2010.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keim SM, Rein JA, Chisholm C, et al. A standardized letter of recommendation for residency application. Acad Emerg Med. 1999;6(11):1141–1146. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1999.tb00117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Council Of Emergency Medicine Residency Directors . Standard Letter of Recommendation. [Accessed May 13, 2011]. 1995. Available at: http://www.cordem.org/i4a/pages/index.cfm?pageid=3284. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Girzadas DV, Jr., Harwood RC, Dearie J, Garrett S. A comparison of standardized and narrative letters of recommendation. Acad Emerg Med. 1998;5(11):1101–1104. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1998.tb02670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Girzadas DV, Harwood RC, Delis SN, et al. Emergency medicine standardized letter of recommendation: predictors of guaranteed match. Acad Emerg Med. 2001;8(6):648–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2001.tb00179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prager JD, Perkins JN, McFann K, et al. Standardized letter of recommendation for pediatric fellowship selection. Laryngoscope. 2012;122(2):415–24. doi: 10.1002/lary.22394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prager JD, Myer CM, Hayes KM, Pensak ML. Improving methods of resident selection. Laryngoscope. 2010;120(12):2391–8. doi: 10.1002/lary.21022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bent JP, Colley PM, Zahtz GD, et al. Otolaryngology resident selection: do rank lists matter? Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;144(4):537–41. doi: 10.1177/0194599810396604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Puscas L, Sharp SR, Schwab B, Lee WT. Qualities of residency applicants: comparison of otolaryngology program criteria with applicant expectations. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;138(1):10–4. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2011.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sharp S, Puscas L, Schwab B, Lee WT. Comparison of applicant criteria and program expectations for choosing residency programs in the otolaryngology match. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;144(2):174–9. doi: 10.1177/0194599810391722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harris Pa., Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measure of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fleiss JL. Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions. Second Edi. John Willey & Sons Inc.; New York: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kendall MG. Rank Correlation Methods. Second Edi. Charles Griffin & Co. Ltd.; London: 1955. [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Resident Matching Program 2012 Results and Data. Washington, D.C.: [Accessed May 30, 2012]. 2012. p. 5. Available at: http://www.nrmp.org/data/resultsanddata2012.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takayama H, Grinsell R, Brock D, et al. Is it appropriate to use core clerkship grades in the selection of residents? Curr Surg. 2006;63(6):391–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cursur.2006.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borowitz SM, Saulsbury FT, Wilson WG. Information collected during the residency match process does not predict clinical performance. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154(3):256–60. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.154.3.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oyama LC, Kwon M, Fernandez Ja, et al. Inaccuracy of the global assessment score in the emergency medicine standard letter of recommendation. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(Suppl 2):S38–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00882.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Girzadas DV, Harwood RC, Davis N, Schulze L. Gender and the council of emergency medicine residency directors standardized letter of recommendation. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11(9):988–91. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2004.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]