Abstract

Objective:

To compare and study the dipeptidy1 peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors in combination with metformin against established combination therapies.

Materials and Methods:

This 16-week study was designed to compare sitagliptin versus pioglitazone as add-on therapy in patients of type 2 diabetes mellitus inadequately controlled with metformin alone. Fifty-two patients were randomized into two groups to receive either sitagliptin 100 mg (group 1) or pioglitazone 30 mg (group 2) in addition to metformin. The primary efficacy end point was change in HbA1c. Secondary end points included change in fasting plasma glucose (FPG), body weight and lipid profile. Treatment satisfaction was assessed using the Diabetes Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire. Both the groups had a significant decrease in HbA1c.

Results:

There was no significant difference between mean reductions in FPG in both the groups. There was a significant decrease in the mean body weight and body mass index in group 1 in contrast to the significant increase in the same in group 2. Both the treatment groups reported a significant decrease in High-density lipoprotein (HDL-C) and Triglyceride.

Conclusion:

Sitagliptin was well tolerated without any incidence of hypoglycemia. It was concluded that sitagliptin as an add-on to metformin is as effective and well tolerated as pioglitazone.

Keywords: DPP-4 inhibitors, diabetes mellitus, add-on therapy

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes mellitus is a chronic metabolic disease affecting at least 171 million people worldwide. This figure is likely to be more than double to 366 million (76.4 million in India) by 2030.[1] Oral antihyperglycemic agents are prescribed if lifestyle measures alone fail to control disease progression. Metformin is the most commonly prescribed first-line antidiabetic drug worldwide. Combination therapy usually becomes necessary in diabetes treatment due to the progressive worsening of blood glucose control with disease advancement.[2] Pioglitazone is commonly prescribed in combination with metformin when the latter fails to control blood glucose alone. The efficacy of pioglitazone plus metformin combination therapy has been proven in such patients in several randomized, placebo or active comparator-controlled trials of up to 3.5 years duration.[3] However, Thiazolidinediones (TZDs) have been found to be associated with a number of adverse events including edema, weight gain and osteoporosis. In addition, rosiglitazone has fallen into disrepute recently for being associated with deranged lipid profile and myocardial infarction.[4]

Sitagliptin is an orally administered once-daily, potent and highly selective dipeptidy1 peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitor for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. DPP-4 inhibitors enhance the levels of active incretin hormones, glucagon-like petide-1 (GLP-1) and glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide (GIP), gut-derived peptides that are released into the circulation after ingestion of meals.[5] In the presence of elevated glucose concentrations, GLP-1 lowers glucagon secretion, thereby decreasing the postprandial rise in glucose concentration and reducing fasting glucose concentrations.[5] Sitagliptin has been approved both as monotherapy and as add-on to existing first-line antidiabetic agents like metformin.[5]

There have been very few studies that have compared DPP-4 inhibitors in combination with metformin against existing established combination therapies for diabetes mellitus. Also, there is paucity of data regarding the effect of DPP-4 inhibitors on treatment satisfaction and lipid profile.

The present study was a randomized, parallel group study of 16 weeks, designed to compare sitagliptin versus pioglitazone as add-on therapy in patients of type 2 diabetes mellitus inadequately controlled on metformin alone.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

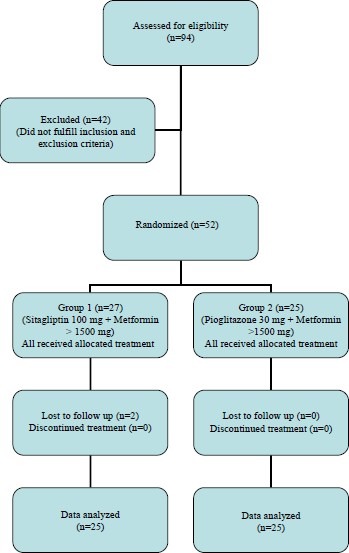

The study was conducted in the Diabetes Clinic of Lok Nayak Hospital, jointly by the Departments of Pharmacology and Internal Medicine, Maulana Azad Medical College & Associated Hospitals, New Delhi. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee. Written informed consent was taken from all the study participants. The patients were enrolled and randomly allocated by a computer-generated block randomization using Research Randomizer (website www.randomizer.org) in two arms [Figure 1]. Patients of either sex aged ≥ 18 years with type 2 diabetes mellitus, on metformin monotherapy of ≥ 1500 mg/day for at least 1 month, having HbA1c 7.5-11% and fasting plasma glucose (FPG) ≥140 mg/dL, were included in the study. Those with type 1 diabetes mellitus, FPG > 270 mg/dL, HbA1c > 11%, severe cardiovascular diseases, Alanine transaminase/Aspartate transaminase (ALT/AST) more than three-times normal or direct bilirubin more than 1.3-times normal or kidney diseases (serum creatinine more than 1.5 mg/dL) were excluded.

Figure 1.

Study flowchart

Fifty-two patients were divided into two groups to receive either sitagliptin 100 mg (group 1) or pioglitazone 30 mg (group 2) in addition to their usual doses of metformin. The sample size was calculated with reference to the previously published literatures and feasibility of completing it on time. The patients were followed-up on weeks 4, 12 and 16. Concurrent lipid-lowering agents, antihypertensive agents and thyroid medications were continued without making any change.

The primary efficacy end point was change in HbA1c from week 0 to 16. Secondary end points included change in FPG, body weight and lipid profile. Any adverse event in either group occurring during the study period was also recorded. Treatment satisfaction was assessed using the Diabetes Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire (DTSQ) – change version (DTSQc).[6]

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was done using computer software SPSS 16.0 version. P value of < 0.05 was considered significant. The data collected at 0 week were used as the baseline against which changes during therapy were compared. Change in HbA1c was calculated by ANCOVA model using various covariates. All statistical tests were two-sided, and the results are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

RESULTS

Demographic and baseline characters

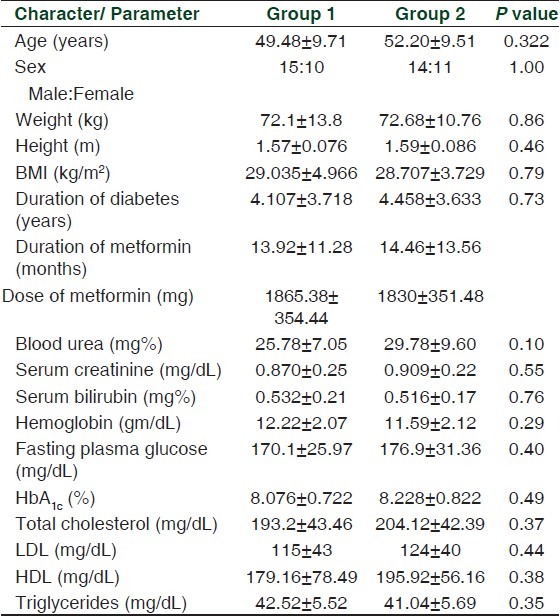

A total of 94 patients were screened from December 2008 to November 2009. Of these, 42 subjects were excluded because of nonfulfillment of inclusion and exclusion criteria. Of the 52 patients who entered the study, two were lost to follow-up [Figure 1]. The baseline demographic characters and biochemical parameters of the enrolled patients are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic characters and biochemical parameters of the enrolled patients

Efficacy end points

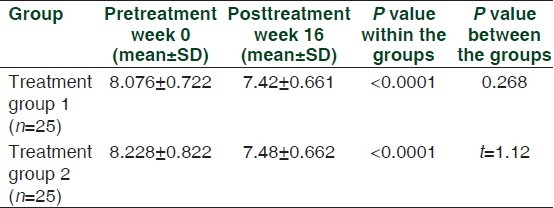

Primary end point (glycosylated hemoglobin)

Group 1 and group 2 had similar baseline HbA1c levels at 0 week. Both the groups had a significant decrease in HbA1c after 16 weeks of administering the respective study drug in combination with metformin. Change in HbA1c from baseline to end in group 1 was -0.656 ± 0.21%, whereas it was -0.748 ± 0.35% in group 2. The difference between the changes produced in the two groups was not statistically significant [Table 2]. Of those included in the study, 24% (n = 6) of the patients in group 1 and 28% (n = 7) in group 2 achieved the study goal of HbA1c < 7%. However, this difference was not statistically significant.

Table 2.

Comparison of mean difference in pre-and posttreatment values of glycosylated hemoglobin in the two treatment groups

Secondary end points

FPG

The two treatment groups had comparable FPG at baseline. At the end of 16 weeks, both group 1 and group 2 reported significant reduction in FPG to 150.52 ± 26.06 mg/dL (mean reduction in FPG from baseline 19.58 mg/dL) and 146.52 ± 23.15 mg/dL (mean reduction in FPG from baseline 30.38 mg/dL), respectively. However, there was no significant difference between mean reductions in FPG in both the groups.

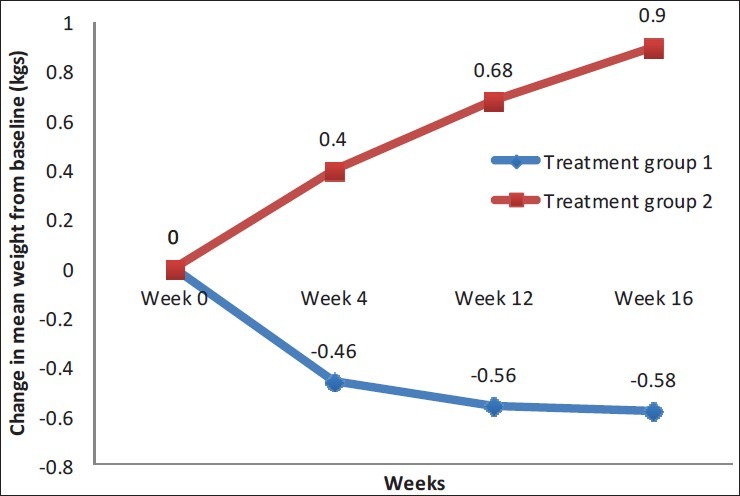

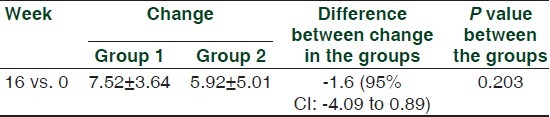

Body weight

A mean decrease of 0.58 kg was seen in treatment group 1 from a baseline mean weight of 72.1 ± 13.76 kg after 16 weeks, and this change was statistically significant. In contrast to this, subjects of group 2 had a mean increase of 0.90 kg in their weight from a baseline level of 72.68 ± 10.83 kg, which was also statistically significant [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Comparative mean weight change in both groups

The patients in group 1 reported a significant decrease in body mass index (BMI) from a mean BMI of 29.03 ± 4.96 kg/m2 while those in group 2 had a significant increase in BMI from a mean BMI of 28.71 ± 3.73 kg/m2 at the end of 16 weeks. This difference observed between the groups was also statistically significant.

Lipid profile

The mean serum TG in group 1 and group 2 also reported a significant decrease during the study period; 10 ± 9.93 mg/dL and 17.8 ± 9.09 mg/dL, respectively. This difference between the two groups was statistically significant. A significant increase in HDL-C levels was also observed in both groups; from 42.52 ± 5.51 mg/dL to 43.68 ± 5.45 mg/dL and 41.04 ± 5.69 mg/dL to 44.12 ± 6.08 mg/dL in group 1 and group 2, respectively.

Other biochemical and clinical parameters

The change in blood pressure, hemoglobin, total leukocyte count (TLC), liver function tests (LFTs) and Kidney function tests (KFTs) at the end of the study from baseline was not significant in either within the group or between the two groups (P > 0.05).

Treatment satisfaction (DTSQs score)

The DTSQ consists of two separate surveys. The original DTSQs (status version) was designed to make the initial assessment of total diabetes treatment satisfaction, treatment satisfaction in specific areas and perceived frequencies of hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia. The change version (DTSQc) has the same eight items as the status version, but reworded slightly to measure the change in satisfaction rather than the absolute satisfaction. It was developed to overcome ceiling effects in the status version.[6]

As evaluated through DTSQc, there was a significant improvement in the treatment satisfaction in both the groups at the end of the study as compared with the treatment satisfaction before beginning add-on therapy. Improvement in the treatment satisfaction was higher in the patients of treatment group 1, but this difference was not statistically significant from treatment group 2 (P = 0.2) [Table 3].

Table 3.

Comparison of mean difference in treatment satisfaction in the two treatment groups using diabetes treatment satisfaction questionnaire change version

Adverse events

In the present study, both the treatments were well tolerated and were not associated with treatment-related serious adverse events. Of the patients in group 1, one each reported headache, diarrhea and nausea. Two patients each reported headache and edema in group 2.

DISCUSSION

The patients in our study were slightly younger in age, with lesser BMI, and had diabetes for a lesser duration. This may be due to the fact that the study population was entirely urban Indian in contrast to other studies that were multicentric, having mainly Caucasian participants. Indians have a greater risk of acquiring diabetes at a much earlier age than the western population in spite of their lower average BMI.[7,8]

The mean decrease in HbA1c (0.66%) in the sitagliptin-treated group was comparable to the previous study reported by Charbonnel et al. (HbA1c reduction 0.65% in sitagliptin + metformin after 24 weeks). However, similar studies by Hermansen et al., Scott et al. and Ludvik et al. reported a greater decrease in the HbA1c level in the sitagliptin + metformin group, i.e. 0.74% reduction after 24 weeks, 0.73% reduction after 18 weeks and 1.13% reduction after 24 weeks, respectively.[9–12] Hermansen et al. followed a washout period of antidiabetic drugs that would have resulted in a significant rise in HbA1c values before initiation of combination therapy.[10]

A recent 18-week study by Reasner et al. reported mean change from baseline HbA1c -2.4% in the sitagliptin + metformin FDC group compared with -1.8% reductions in the metformin monotherapy group.[13] This greater decrease in HbA1c may be attributed to the fact that patients enrolled in the study were treatment naïve (mean baseline HbA1c 9.9%), whereas our study population was treatment experienced (mean baseline HbA1c 8.076%).

The mean decrease in HbA1c in the pioglitazone-treated group of our study was 0.75%. Similar studies by Einhorn et al., Bolli et al. and Matthews et al. reported a greater decrease in the HbA1c level in the pioglitazone + metformin group; 1.36% reduction after 72 weeks, 0.9% reduction after 24 weeks and 1% reduction after 52 weeks, respectively.[14–16] This difference may be ascribed to the longer duration of drug treatment in these studies.

In our study, 24% of the patients in the sitagliptin-treated group achieved the goal of < 7% HbA1c level. A similar 18-week study of sitagliptin as an add-on to metformin therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus by Raz et al. reported 22% patients reaching the goal of < 7% HbA1c.[17] However, some other previous studies showed a larger proportion of patients achieving the goal of HbA1c with sitagliptin (55% Scott et al., 63% Nauck et al.).[11,18] The difference with Scott et al. can be explained by the fact that baseline mean HbA1c was higher in our study (Scott et al. 7.7% vs. 8.076% our study). Nauck et al. reported the proportion of patients reaching the goal of < 7% HbA1c level after 52 weeks whereas we reported this after 16 weeks.[18]

The reduction in FPG obtained with sitagliptin (19.58 mg/dL after 16 weeks) in this study was consistent with those observed by Hermansen et al. (20.1 mg/dL after 24 weeks).[10] Ludvik et al. reported a greater decrease in FPG (36.3 mg/dL after 24 weeks).[12] The FPG reduction with pioglitazone (30.38 mg/dL) in our study was slightly lesser than that observed by Bolli et al. (38 mg/dL after 24 weeks) and Matthews et al. (34.2 mg/dL after 52 weeks). Einhorn et al. reported a greater decrease in FPG in the pioglitazone + metformin group (63 mg/dL after 72 weeks), which may be attributed to the longer duration of the study.[14–16]

The pioglitazone group in our study reported an increase in the mean body weight (0.9 kg after 16 weeks). This was less than that in previous studies by Bolli et al. (1.9 kg after 24 weeks) and Umpierrez et al. (1.74 kg after 26 weeks).[15,19] A possible explanation could be greater adherence to dietary advice and smaller duration of study.

On the other hand, weight decreased in the sitagliptin group during the first 4 weeks of treatment, and then remained almost stable. Similar to changes in weight, BMI also increased in the pioglitazone group, while they decreased in the sitagliptin group. Based on the results from other studies in combination with metformin, sitagliptin appears to be largely weight-neutral, with results varying from weight gain observed by Hermansen et al. (24 weeks + 0.8 kg), no effect on body weight as seen by Raz et al. (30 weeks, no effect) to body weight reduction studied by Scott et al. (18 weeks, -0.4kg), Nauck et al. (52 weeks, -1.5 kg) and Ludvik et al. (24 weeks, -2.8 kg).[10–12,17,18] Weight gain in the treatment of diabetes may contribute further insulin resistance and reduce treatment adherence. Thus, the weight neutrality of DPP-4 inhibitors may offer a great therapeutic advantage in diabetes management.[19]

Regarding fasting lipid levels, both sitagliptine and pioglitazone had a similar impact on each of the parameters, with an increase in HDL-C and a decrease in the triglyceride levels. However, the extent to which HDL-C levels and triglyceride levels were affected favorably with pioglitazone was greater than that with sitagliptin (difference between groups each P < 0.05). There is paucity of data in the literature regarding the effect of sitagliptine on lipid profile. A study done by Tremblay has shown similar effects on lipid profile as our study.[20]

A previous study has demonstrated the favorable effect of pioglitazone on TG and HDL.[21,22] In patients with type 2 diabetes, there is a strong association between high triglyceride and low HDL cholesterol levels and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.[22] There have been concerns over liver toxicity with TZDs.[23] In our study, both sitagliptin and pioglitazone caused slight, nonsignificant elevation in mean levels of hepatic enzymes.

The most common adverse effect noted to occur in clinical trials with DPP-4 inhibitors are nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory infection and headache.[24] Recently, the USFDA has issued a safety alert for sitagliptin regarding acute pancreatitis due to several postmarketing cases reported to the agency (88 reports of acute pancreatitis between October 2006 and February 2009).[25] In our study, the most frequent side-effects reported with sitagliptin were headache, diarrhea and nausea. Diarrhea and vomiting could be attributable to metformin also as it is known to cause gastrointestinal side-effects.[26] Edema and weight gain were the most common adverse events reported in the pioglitazone group, and these have also been corroborated previously with pioglitazine as combination with metformin.[15,16]

Patient's satisfaction with the ongoing treatment is an important indicator of good compliance, which eventually leads to the success of treatment. Treatment satisfaction scores from the DISQs and DTSQc, filled pre- and posttreatment revealed that the treatment satisfaction for both the treatment groups using sitagliptin or pioglitazone in combination with metformin was significantly higher. There was no significant difference in the improvement in treatment satisfaction produced in the two groups, although this was higher with sitagliptin.

Because diabetes is a chronic disease, with patients often having the need of lifelong therapy, cost becomes an important factor in choosing antidiabetic medication. Cost analysis was not in the scope of the present study. More pharmacoeconomic studies on Indian patients are required before coming to a conclusive evidence regarding the cost-effectiveness of sitagliptin.

CONCLUSIONS

Sitagliptin as an add-on to metformin is as effective and well tolerated as pioglitazone, but does not cause edema or weight gain. In view of its efficacy and good tolerability profile, sitagliptin may be a useful addition to the existing therapeutic armamentarium for treatment of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Studies with large sample size and longer follow-up period are required for validating our results regarding the noninferiority of DPP-4 inhibitors versus TZDs as add-on therapy to metformin and their effect on treatment satisfaction or lipid profile.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nill,

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, Sicree R, King H. Global prevalence of diabetes: Estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1047–53. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.5.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Turner RC, Cull CA, Frighi V, Holman RR. Glycemic control with diet, sulfonylurea, metformin, or insulin in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: Progressive requirement for multiple therapies (UKPDS 49). UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. JAMA. 1999;281:2005–12. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.21.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deeks ED, Scott LJ. Pioglitazone/metformin. Drugs. 2006;66:1863–77. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200666140-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mohan V, Joshi SR. The Rosiglitazone Controversy: The Indian Perspective. J Assoc Physicians India. 2007;55:477–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gallwitz B. Review of sitagliptin phosphate: A novel treatment for type 2 diabetes. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2007;3:203–10. doi: 10.2147/vhrm.2007.3.2.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradley C, Lewis KS. Measures of psychological well-being and treatment satisfaction developed from the responses of people with tablet-treated diabetes. Diabet Med. 1990;7:445–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.1990.tb01421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mohan V, Sandeep S, Deepa R, Shah B, Varghese C. Epidemiology of type 2 diabetes: Indian scenario. Indian J Med Res. 2007;125:217–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wulan SN, Westerterp KR, Plasqui G. Ethnic differences in body composition and the associated metabolic profile: A comparative study between Asians and Caucasians. Maturitas. 2010;65:315–9. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2009.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Charbonnel B, Karasik A, Liu J, Wu M, Meininger G. Sitagliptin study 020 group.Efficacy and safety of the dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor sitagliptin added to ongoing metformin therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled with metformin alone. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:2638–43. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hermansen K, Kipnes M, Luo E, Fanurik D, Khatami H, Stein P. Sitagliptin study 035 group.Efficacy and safety of the dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor, sitagliptin, in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus inadequately controlled on glimepiride alone or on glimepiride and metformin. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2007;9:733–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2007.00744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scott R, Loeys T, Davies MJ, Engel SS. Sitagliptin Study 801 Group.Efficacy and safety of sitagliptin when added to ongoing metformin therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2008;10:959–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2007.00839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ludvik B, Daniela L. Efficacy and tolerability of sitagliptin in type 2 diabetic patients inadequately controlled with metformin. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2011;123:235–40. doi: 10.1007/s00508-011-1559-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reasner C, Olansky L, Seck TL, Williams-Herman DE, Chen M, Terranella L, et al. The effect of initial therapy with the fixed-dose combination of sitagliptin and metformin compared with metformin monotherapy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2011;13:644–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2011.01390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Einhorn D, Rendell M, Rosenzweig J, Egan JW, Mathisen AL, Schneider RL. Pioglitazone hydrochloride in combination with metformin in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus: A randomized, placebo-controlled study.The Pioglitazone 027 Study Group. Clin Ther. 2000;22:1395–409. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(00)83039-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bolli G, Dotta F, Rochotte E, Cohen SE. Efficacy and tolerability of vildagliptin vs. pioglitazone when added to metformin: A 24-week, randomized, double.blind study. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2008;10:82–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2007.00820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matthews DR, Charbonnel BH, Hanefeld M. Long-term therapy with addition of pioglitazone to metformin compared with the addition of gliclazide to metformin in patients with type 2 diabetes: A randomized, comparative study. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2005;21:167–74. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raz I, Chen Y, Wu M, Hussain S, Kaufman KD, Amatruda JM, et al. Efficacy and safety of sitagliptin added to ongoing metformin therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24:537–50. doi: 10.1185/030079908x260925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nauck MA, Meininger G, Sheng D, Terranella L, Stein PP. Sitagliptin study 024 group.Efficacy and safety of the dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor, sitagliptin, compared with the sulfonylurea, glipizide, in patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled on metformin alone: A randomized, double-blind, non-inferiority trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2007;9:194–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2006.00704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bourdel-Marchasson I, Schweizer A, Dejager S. Incretin therapies in the management of elderly patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Hosp Pract (Minneap) 2011;39:7–21. doi: 10.3810/hp.2011.02.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tremblay AJ, Lamarche B, Deacon CF, Weisnagel SJ, Couture P. Effect of sitagliptin therapy on postprandial lipoprotein levels in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2011;13:366–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2011.01362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berhanu P, Kipnes MS, Khan MA, Perez AT, Kupfer SF, Spanheimer RG, et al. Effects of pioglitazone on lipid and lipoprotein profiles in patients with type 2 diabetes and dyslipidaemia after treatment conversion from rosiglitazone while continuing stable statin therapy. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2006;3:39–44. doi: 10.3132/dvdr.2006.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pfützner A, Schöndorf T, Tschöpe D, Lobmann R, Merke J, Müller J, et al. PIOfix-Study: Effects of pioglitazone/metformin fixed combination in comparison with a combination of metformin with glimepiride on diabetic dyslipidemia. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2011;13:637–43. doi: 10.1089/dia.2010.0233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tolman KG, Freston JW, Kupfer S, Perez A. Liver safety in patients with type 2 diabetes treated with pioglitazone: Results from a 3-year, randomized, comparator-controlled study in the US. Drug Saf. 2009;32:787–800. doi: 10.2165/11316510-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baetta R, Corsini A. Pharmacology of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors: Similarities and differences. Drugs. 2011;71:1441–67. doi: 10.2165/11591400-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sitagliptin (marketed as Januvia and Janumet)-acute pancreatitis FDA safety information. [Online]. 2009 September 25. [Last cited on 2010 Jan 07]. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/SafetyInformation/SafetyAlertsforHumanMedicalProducts/ucm183800.htm .

- 26.Schwarz B, Gouveia M, Chen J, Nocea G, Jameson K, Cook J, et al. Cost-effectiveness of sitagliptin-based treatment regimens in European patients with type 2 diabetes and haemoglobinA1c above target on metformin monotherapy. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2008;10:43–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2008.00886.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]