Abstract

Background:

The term gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) is used to refer to those mesenchymal neoplasms of the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) which express CD117, a c-kit proto-oncogene protein.

Aims:

To study the cytological features of GIST and extra-gastrointestinal stromal tumors (EGIST), to correlate them with histology and to determine cytological indicators of malignancy.

Materials and Methods:

Cytological smears from patients diagnosed as GIST/EGIST on histology were retrieved. From Jan 2000 to July 2010, 26 GIST (13 primary, 12 metastatic, one recurrent) and seven EGIST (5 primary, one metastatic, one recurrent) cytologic samples from 27 patients were identified.

Results:

The patients included 20 males and 7 females with a mean age of 50.6 years. Tumor sites included stomach (5), duodenum (5), ileum (2), ileocecal (1), rectum (1), liver (9), retroperitoneum (5), mesentery (1), subcutaneous nodule (1), supra-penile lump (1), ascitic (1) and pleural fluids (1). The smears were cellular with cohesive to loosely cohesive thinly spread irregularly outlined cell clusters held together by thin calibre vessels. The tumor cells were mild to moderately pleomorphic, spindle to epithelioid with variable chromatin pattern and variable cytoplasm. Cellular dyscohesion, nuclear pleomorphism, intranuclear pseudoinclusions, prominent nucleoli, mitosis and necrosis were more prominent in malignant, metastatic and recurrent tumors.

Conclusions:

GISTs show a wide spectrum of cytological features and the presence of mitosis, necrosis and nuclear pleomorphism can help in prediction of malignant behavior. Further, cytology is a very useful screening modality in patients of GIST and EGIST to detect early recurrence and metastasis at follow-up.

Keywords: Cytology, fine needle aspiration, gastrointestinal stromal tumors, malignant

Introduction

Primary mesenchymal tumors of the intestinal tract are a heterogeneous group of tumors with a wide clinical spectrum ranging from benign incidentally detected nodules to frank malignant tumors. Traditionally the majority of these tumors were thought to be derived from smooth muscle cells.[1,2] It has now been realized that the majority of these tumors are not smooth muscle or nerve sheath tumors, but represent a distinct clinico-pathological entity termed as gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST). It is currently believed that GIST is a specific mesenchymal neoplasm and the term is used to refer to those mesenchymal neoplasms of the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) which express CD117, a c-kit proto-oncogene protein, and show gain of function mutation of c-kit gene that encodes a growth factor receptor with tyrosine kinase activity.[3,4] The introduction of a new targeted treatment for GIST in the form of imatinib mesylate, a receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, has further validated this entity.[5,6]

GIST can occur at all levels of GIT and may also arise in extra-GI locations, principally mesentery, omentum and retroperitoneum and occasionally in pancreas. Approximately 50-60% of GISTs arise in the stomach, 20-30% in small bowel, 10% in large bowel and 5% in esophagus. About 30% of GIST are malignant and liver is the most common site for metastasis.[7–10] The criteria for differentiation of benign from malignant GIST remain controversial. Many parameters have been proposed, tumor size and proliferative activity have been found to be the most important prognostic indicators.[11,12] GIST reported outside the GIT t as apparent primary tumors are designated as extra-gastrointestinal stromal tumor (EGIST).[12–14] The frequency of EGIST is only 5-7%.

Because of overlapping morphology, GISTs are cytologically difficult to distinguish from other gastrointestinal mesenchymal neoplasms including smooth muscle tumors and nerve sheath tumors.[15–19] Although many investigators have described various features used in the cytologic diagnosis of GIST, few have reported their findings in patients with malignant GIST. The present study is the largest series discussing the cytology of GISTs and EGIST from different anatomic sites including extremely rare sites like subcutaneous nodules, fluid cytology samples and metastasis from a primary pancreatic EGIST. In the present study we studied the cytomorphological features in 33 GIST/EGIST from 27 patients. We also evaluated cytologic features which could suggest malignant potential of GIST on cytology.

Materials and Methods

All patients of histologically and immunohistochemically confirmed GIST and EGIST who underwent cytological examination over a period of ten years (Jan 2000-July 2010) were retrieved from the records of the Department of Pathology. 33 specimens from 27 patients including 26 GIST (13 primary, 12 metastatic, one recurrent) and seven EGIST (5 primary, 1 metastatic, 1 recurrent) were identified. These included guided (28) and unguided (2) fine-needle aspirates, imprint smear (1) and fluid cytology (2). Fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) was performed using 22 gauge needle attached to 10 mL disposable syringe under ultrasound guidance of intra-abdominal tumors. FNA material was smeared on glass slides and slides fixed in 95% alcohol were stained with Papanicolaou and hematoxylin and eosin stain while air dried smears were stained with May-Grünwald-Giemsa stain (MGG). The ascitic and pleural fluids were cytocentrifuged and smears prepared. The clinical data were recorded from the hospital information system and case files. Histological categorization of GIST of different sites into various risk groups was done as suggested recently by Miettinen et al.[12] Cytology was reviewed in all cases with emphasis on the following cytological features: Overall cellularity, smear pattern (cohesion vs. dispersed cells), palisading, crush artefact, prominent vascular pattern, spindle versus epithelioid cell morphology, nuclear grooves and inclusions, nuclear pleomorphism, presence of nucleoli, round or blunt-ended oval or wavy nuclei, multinucleation/bizarre cells/or giant cells, perinuclear vacuoles, cytoplasmic quality, mitoses and necrosis.

Results

The patients included 20 males and 7 females with male: female ratio of 2.67:1. The mean age was 50.6 years (range: 26-76, median: 52 years). Thirty three cytologic samples from 27 patients were available for review. There were 18 primary tumours (5 gastric, 5 duodenum, 1 ileum, 1 ileocecal, 1 rectum, 4 intra-abdominal/retroperitoneal tumours, 1 mesentery), 9 hepatic metastases (5 gastric, 2 duodenum, 1 jejunum, 1 small bowel primary tumours), 1 ascitic fluid metastases (gastric primary), 1 pleural fluid metastases (jejunum primary), 1 subcutaneous nodule metastases (gastric primary), 1 lump at base of penis (rectum primary) and 2 recurrences (1 ileum, 1 intra-abdominal/retroperitoneal).

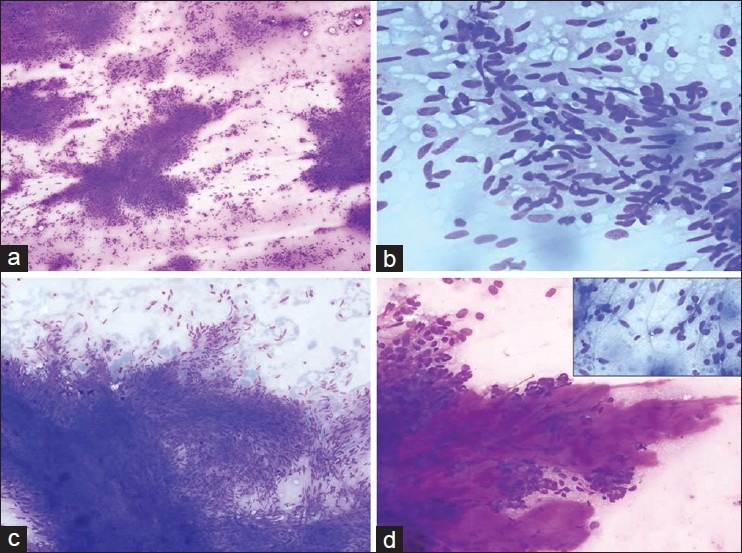

The smears were variably cellular. Low grade tumors were more commonly low to moderately cellular. Malignant and metastatic lesions were commonly highly cellular. In patients with predominantly spindle cells on cytology (n = 18) smears showed cells often arranged in cohesive to loose three dimensional clusters and singly scattered or dispersed cells [Figure 1a and b]. The tumor cells often formed fascicles with parallel, side-by-side arrangements of nuclei. In these fascicles tumor cells were oriented or organized in one direction (streaming). Nuclear palisading was found in eight cases [Figure 1c]. The stroma of the cohesive sheets present between the nuclei was loosely fibrillary and stained pink to magenta on MGG [Figure 1d]. The tumor cells had, ovoid to elongated or irregular-shaped nuclei. The chromatin was finely to coarsely granular. The cytoplasm had a distinctive delicate fibrillary quality with numerous wispy cytoplasmic extensions. Bipolar cytoplasmic processes were often observed in spindle cell tumors. Cytoplasmic vacuoles were sometimes seen in perinuclear location. Extra-cellular myxoid material was also present. Skenoid fibres were noted in a smear from liver metastasis of a patient with primary jejunal GIST. Focally, tumors exhibited vascular patterns with tumor cells arranged as perivascular clusters. Many tumors also showed “stripped” or “bare” spindle nuclei in background.

Figure 1.

Spindle cells with high cellularity, closely packed to loose clusters and dyscohesive cells (MGG, ×100); (a) Spindle cells displaying elongated to wavy nuclei with blunt to tapered ends (MGG, ×200); (b) Fascicles with parallel, side-by-side arrangements of nuclei with scant cytoplasm. Nuclear palisading is also observed (MGG, ×100); (c) Abundant extracellular stromal material (MGG, ×200); (d) (Inset: Spindle cells with bipolar cytoplasmic processes (MGG, ×400)

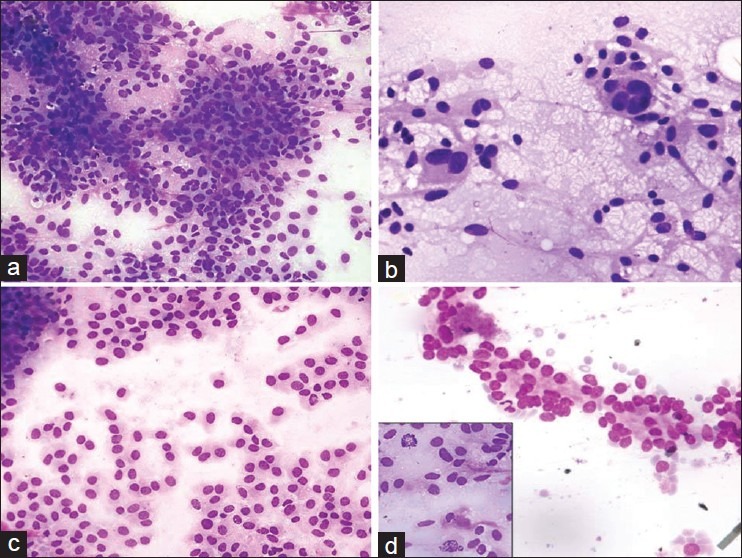

Focal to diffuse epithelioid cell morphology admixed with spindle cells were observed in twelve samples and 3 tumors had only epithelioid cell type [Figure 2a]. Epithelioid morphology was more commonly seen in malignant and metastatic tumors. Binucleation and multinucleation was noted [Figure 2b]. Plasmacytoid appearance was noted in eight samples [Figure 2c] Few demonstrated rossetting and acinar structure arrangement reminiscent of adenocarcinoma [Figure 2d]. These cells displayed round nuclei with regular to irregular nuclear membrane. The nucleoli were indistinct in low grade tumors and prominent or multiple nucleoli were seen in high grade tumors irrelevant of cell type. Intranuclear inclusions were also noted in malignant tumors. The presence of marked cytologic atypia with presence of bizarre and giant cells was identified in 6 tumors. Occasional tumors displayed bubbly appearance due to multiple cytoplasmic vacuoles. In 9 cases mitotic figures were observed. The pleural and ascitic fluid cytology smears exhibited loosely formed aggregates with epithelioid cell morphology. Nuclear pleomorphism, opened up chromatin, conspicuous nucleoli were noted. Necrosis was appreciated in a primary retroperitoneal tumor and in ascitic fluid specimen.

Figure 2.

Smear showing groups of epithelioid tumors cells with round nuclei (MGG, ×200); (a) Multinucleation (MGG, ×400); (b) Plasmacytoid tumor cells displaying eccentric round nuclei with smooth nuclear membrane and fine chromatin (MGG, ×400); (c) Acinar arrangement of tumor cells mimicking epithelial tumor (MGG, ×400); (d) (Inset: Mitotic figure in a mixed GIST (MGG, ×400)

Histology sections of all primary GIST and EGIST were reviewed. The majority (N = 18, 66.67%) of tumors were classified as spindle cell type, while 3 (11.12%) were classified as epithelioid type and 6 (22.23%) as mixed cell type. The cellularity of the majority of tumors was subjectively assessed as moderate (N = 17). Histology sections of all the low cellularity smears showed moderate to high cellularity. The majority of EGISTs were of high cellularity. Nuclear pleomorphism was moderate to marked in majority of cases. The mitotic count ranged between 0-39/5 mm2. Categorization of GIST of different sites into various risk groups was performed as suggested recently by Miettinen et al.[12] There was only one low grade tumor, 4 tumors with moderate risk, and 22 tumors were categorized as high risk. Immunohistochemically all tumors were positive for CD117 with strong intensity of positivity in the majority of tumors. Seventeen tumors (63%) were positive for CD34. SMA positivity was seen in 12 tumors. S100 immunopositivity was seen in 10 tumors. Five tumors were positive for desmin. The range of MIB-1 labeling index was 0.2-21.

Discussion

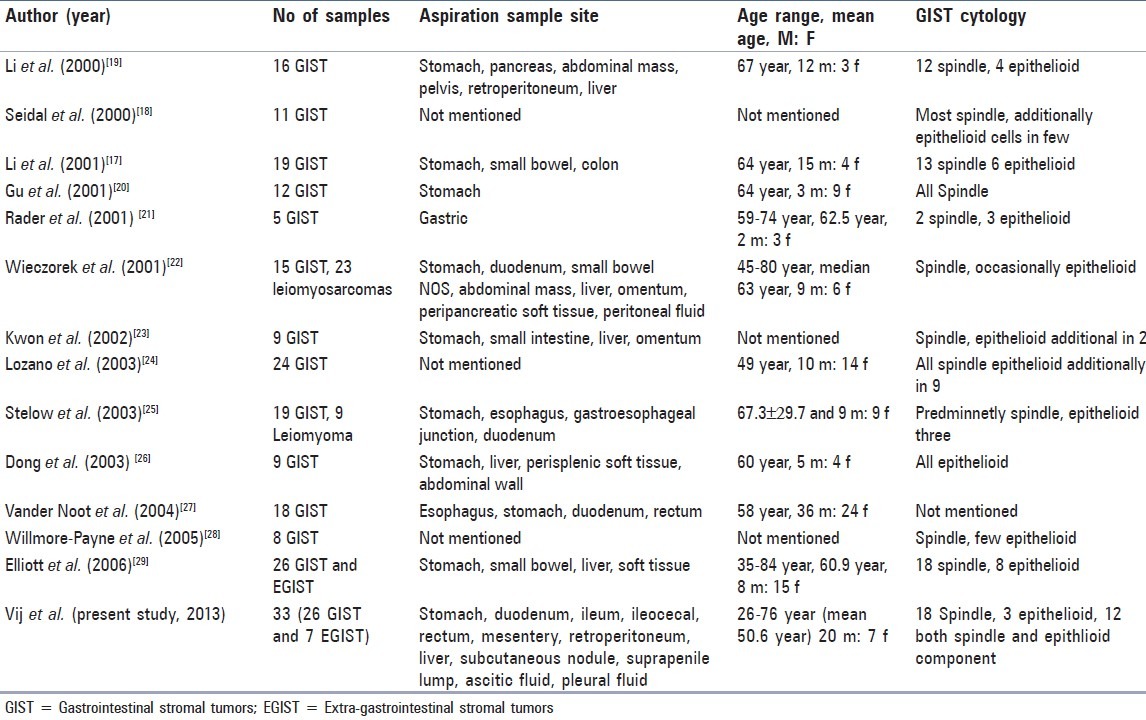

The cytological studies on GIST in literature are not comparable as many of the earlier published cytologic studies have combined GIST into a group of neoplasms encompassing leiomyoma, schwannoma, leiomyosarcoma, and an epithelioid leiomyoblastoma.[15–17] However recently, few authors have established FNAC as a reliable method for diagnosing GIST and EGIST before surgical procedure [Table 1].[18–30] We observed several morphologic features suggestive of high grade GIST and EGIST. In recurrent, metastatic and malignant GIST the cellular groupings were loose along with presence of single cells in the background. The chromatin of tumor nuclei varied from being fine to coarse with occasional macronucleoli. Mitosis was the key morphologic feature that suggested high grade malignant GIST. However, it was difficult to find mitoses in the cytologic smears because most of the tumor cells occurred in closely packed cohesive thick tissue fragments. Li et al.,[18] found that mitoses in the resected malignant GISTs were seldom seen in FNAC smear. We also found that malignant GISTs sometimes had no significant pleomorphism in the cytologic smears. Nuclear inclusions were more commonly seen in malignant and metastatic tumors irrespective of cell type in our cases. Other authors have noted intranuclear inclusion in rare cases or only in epithelioid tumors.[22,27] Dirty or necrotic background again was least reliable indicator of malignancy as it was seen in two samples only. We agree with earlier descriptions that FNA findings alone cannot reliably assess behavior of GIST. Prediction of behavior by cytological features is likely to result in either underestimation or overestimation of malignant potential.[18–25]

Table 1.

Summary of various series of GIST and EGIST cytology cases described in the literature

The differential diagnosis between GISTs and gastrointestinal leiomyomas is difficult owing to their overlapping clinical and cytologic features. Leiomyoma shows varying cellularity and are composed of bland spindle cells with abundant cytoplasm often having a fibrillary appearance.[26] No atypia, mitoses, or epithelioid cells are identified. Gastrointestinal leiomyosarcomas are much rarer than leiomyomas. GIST and LMS may have either a spindled or epithelioid cytomorphology. Leiomyosarcomas shows three-dimensional, tightly cohesive, sharply marginated syncytia of spindle cells, often with nuclear crush artefact.[23] Leiomyosarcomas more commonly exhibits pleomorphism. Epithelioid cytomorphology, mitoses, and necrosis occasionally are observed in both tumor types. Benign and malignant nerve sheath tumors show fibrillar cytoplasm and “wavy” nuclei, similar to a subset of and characteristic features of nerve sheath differentiation, such as nuclear palisading, may be focal. Epithelioid GISTs may cause significant diagnostic confusion with carcinomas, neuroendocrine tumors, and melanoma, particularly when metastatic and even hepatocellular carcinoma.[27] The regular round nuclei, with finely granular chromatin seen in many of cases raised the possibility of neuroendocrine tumor. Key features of melanoma are loose aggregates or isolated cells, cellular pleomorphism, enlarged nuclei with macronucleoli, binucleation, multinucleation and intracytoplasmic melanin. Hepatocellular carcinoma shows neoplastic cells forming trabeculae with endothelial cells lining the groups. Intranuclear inclusions, intracytoplasmic bile pigment and no bile duct epithelium are important distinguishing features. The separation of metastatic GIST from other metastasis is important since these may respond to imatinib.

To conclude, firstly cytology is a useful method for preoperative diagnosis and follow-up of GISTs and EGIST. GIST show a broad morphologic spectrum on cytology and GIST should be considered as a differential diagnosis of tumors with spindle or epithelioid morphology. In an appropriate clinical and radiologic setting the presence of closely packed spindle or oval cells forming fascicles with parallel side-by-side arrangements of nuclei suggests GIST. The diagnosis of GIST should also be considered in aspirates of the gastrointestinal tract, liver, mesentery, or abdominal wall mass lesions when epithelioid cells are the predominant cell type. It is difficult to assess behavior of GISTs on cytology alone. The presence of cellular dyscohesion, nuclear pleomorphism, necrosis and mitosis suggest malignant behavior, however absence of these features on cytology is not diagnostic of low risk benign behavior.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Martin JF, Bazin P, Feroldi J, Cabanne F. Intramural myoid tumors of the stomach. Microscopic considerations on 6 cases. Ann Anat Pathol. 1960;5:484–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stout AP. Bizarre smooth muscle tumors of the stomach. Cancer. 1962;15:400–9. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196203/04)15:2<400::aid-cncr2820150224>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hirota S, Isozaki K, Moriyama Y, Hashimoto K, Nishida T, Ishiguro S, et al. Gain of function mutations of c-kit in human gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Science. 1998;279:577–80. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5350.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sarlomo-Rikala M, Kovatich AJ, Barusevicius A, Miettinen M. CD117: A sensitive marker for gastrointestinal stromal tumors that is more specific than CD34. Mod Pathol. 1998;11:728–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joensuu H, Roberts PJ, Sarlomo-Rikala M, Andersson LC, Tervahartiala P, Tuveson D, et al. Effect of the tyrosine kinase inhibitor STI571 in a patient with a metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1052–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104053441404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Demetri GD, von Mehren M, Blanke CD, Van den Abbeele AD, Eisenberg B, Roberts PJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of imatinib mesylate in advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:472–80. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steigen SE, Eide TJ. Trends in incidence and survival of mesenchymal neoplasm of the digestive tract within a defined population of northern Norway. APMIS. 2006;114:192–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2006.apm_261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tran T, Davila JA, El-Serag HB. The epidemiology of malignant gastrointestinal stromal tumors: An analysis of 1,458 cases from 1992 to 2000. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:162–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.40709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vij M, Agrawal V, Kumar A, Pandey R. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: A clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of 121 cases. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2010;29:231–6. doi: 10.1007/s12664-010-0079-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vij M, Agrawal V, Pandey R. Malignant extra-gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the pancreas. A case report and review of literature. JOP. 2011;12:200–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fletcher CD, Berman JJ, Corless C, Gorstein F, Lasota J, Longley BJ, et al. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: A consensus approach. Hum Pathol. 2002;33:459–65. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2002.123545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miettinen M, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: Pathology and prognosis at different sites. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2006;23:70–83. doi: 10.1053/j.semdp.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miettinen M, Monihan JM, Sarlomo-Rikala M, Kovatich AJ, Carr NJ, Emory TS, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors/smooth muscle tumors (GISTs) primary in the omentum and mesentery: Clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 26 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:1109–18. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199909000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reith JD, Goldblum JR, Lyles RH, Weiss SW. Extragastrointestinal (soft tissue) stromal tumors: An analysis of 48 cases with emphasis on histologic predictors of outcome. Mod Pathol. 2000;13:577–85. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dodd LG, Nelson RC, Mooney EE, Gottfried M. Fine-needle aspiration of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Am J Clin Pathol. 1998;109:439–43. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/109.4.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tao LC, Davidson DD. Aspiration biopsy cytology of smooth muscle tumors. A cytologic approach to the differentiation between leiomyosarcoma and leiomyoma. Acta Cytol. 1993;37:300–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li SQ, O'Leary TJ, Buchner SB, Przygodzki RM, Sobin LH, Erozan YS, et al. Fine needle aspiration of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Acta Cytol. 2001;45:9–17. doi: 10.1159/000327181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seidal T, Edvardsson H. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumor by fine-needle aspiration biopsy: A cytological and immunocytochemical study. Diagn Cytopathol. 2000;23:397–401. doi: 10.1002/1097-0339(200012)23:6<397::aid-dc7>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li SQ, O'Leary TJ, Sobin LH, Erozan YS, Rosenthal DL, Przygodzki RM. Analysis of KIT mutation and protein expressionin fine needle aspirates of gastrointestinal stromal/smooth muscle tumors. Acta Cytol. 2000;44:981–6. doi: 10.1159/000328620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gu M, Ghafari S, Nguyen PT, Lin F. Cytologic diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the stomach by endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy: Cytomorphologic and immunohistochemical study of 12 cases. Diagn Cytopathol. 2001;25:343–50. doi: 10.1002/dc.10003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rader AE, Avery A, Wait CL, McGreevey LS, Faigel D, Heinrich MC. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy diagnosis of gastrointestinalstromal tumors using morphology, immunocytochemistry and mutational analysis of c-kit. Cancer. 2001;93:269–75. doi: 10.1002/cncr.9041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wieczorek TJ, Faquin WC, Rubin BP, Cibas ES. Cytologic diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumor with emphasis of the differential diagnosis with leiomyosarcoma. Cancer. 2001;93:276–87. doi: 10.1002/cncr.9042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kwon MS, Koh JS, Lee SS, Chung JH, Ahn GH. Fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) of gastrointestinal stromal tumor: An emphasis on diagnostic role of FNAC, cell block, and immunohistochemistry. J Korean Med Sci. 2002;17:353–9. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2002.17.3.353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lozano MD, Rodriguez J, Algarra SM, Panizo A, Sola JJ, Pardo J. Fine-needle aspiration cytology and immunocytochemistry in the diagnosis of 24 gastrointestinal stromal tumors: A quick, reliable diagnostic method. Diagn Cytopathol. 2003;28:131–5. doi: 10.1002/dc.10260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stelow EB, Stanley MW, Mallery S, Lai R, Linzie BM, Bardales RH. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration findings of gastrointestinal leiomyomas and gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Am J Clin Pathol. 2003;119:703–8. doi: 10.1309/UWUV-Q001-0D9W-0HPN. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dong Q, McKee G, Pitman M, Geisinger K, Tambouret R. Epithelioid variant of gastrointestinal stromal tumor: Diagnosis by fine-needle aspiration. Diagn Cytopathol. 2003;29:55–60. doi: 10.1002/dc.10293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vander Noot MR, 3rd, Eloubeidi MA, Chen VK, Eltoum I, Jhala D, Jhala N, et al. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal tract lesions by endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy. Cancer. 2004;102:157–63. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Willmore-Payne C, Layfield LJ, Holden JA. c-KIT mutation analysis for diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors in fine needle aspiration specimens. Cancer. 2005;105:165–70. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elliott DD, Fanning CV, Caraway NP. The utility of fine-needle aspiration in the diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: A cytomorphologic and immunohistochemical analysis with emphasis on malignant tumors. Cancer. 2006;108:49–55. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deshpande A, Munshi MM. Gastrointestinal stromal tumours-report of three cases and review of literature. J Cytol. 2007;24:96–100. [Google Scholar]