Abstract

The Dengue virus (DENV) genome contains multiple cis-acting elements required for translation and replication. Previous studies indicated that a 719-nt subgenomic minigenome (DENV-MINI) is an efficient template for translation and (−) strand RNA synthesis in vitro. We performed a detailed structural analysis of DENV-MINI RNA, combining chemical acylation techniques, Pb2+ ion-induced hydrolysis and site-directed mutagenesis. Our results highlight protein-independent 5′–3′ terminal interactions involving hybridization between recognized cis-acting motifs. Probing analyses identified tandem dumbbell structures (DBs) within the 3′ terminus spaced by single-stranded regions, internal loops and hairpins with embedded GNRA-like motifs. Analysis of conserved motifs and top loops (TLs) of these dumbbells, and their proposed interactions with downstream pseudoknot (PK) regions, predicted an H-type pseudoknot involving TL1 of the 5′ DB and the complementary region, PK2. As disrupting the TL1/PK2 interaction, via ‘flipping’ mutations of PK2, previously attenuated DENV replication, this pseudoknot may participate in regulation of RNA synthesis. Computer modeling implied that this motif might function as autonomous structural/regulatory element. In addition, our studies targeting elements of the 3′ DB and its complementary region PK1 indicated that communication between 5′–3′ terminal regions strongly depends on structure and sequence composition of the 5′ cyclization region.

INTRODUCTION

Unlike cellular mRNAs, which only contain translational regulatory motifs, viral RNA genomes have evolved functional regions, which act at different stages of their life cycle. These specific structures, their interactions and association with host proteins and ligands, together orchestrate the multifunctionality of viral RNA genomes. Often, RNA–RNA interactions spanning significant distances (1,2) bring regulatory motifs into proximity, changing our view of a functional viral RNA genome from that of a linear molecule to one whose 3D structure is an important contributor during the life cycle (3,4).

Organization of the Dengue virus (DENV) genome represents an example of intra-genomic long distance interactions that modulate molecular processes. DENV is a mosquito-borne, single-stranded, positive (+)-sense RNA virus belonging to the Flaviviridae family, whose members are responsible for diseases of major health importance, such as yellow fever, Japanese encephalitis, tick-borne encephalitis, dengue fever and a dengue hemorrhagic fever. The DENV genome encodes a single-open reading frame, flanked by highly structured untranslated regions (UTRs) (5–7). The secondary structure of DENV UTRs has attracted attention, as they have been shown to encompass motifs involved in regulation of translation, replication, transcription and viral pathogenesis (7–10). It has been proposed that the 3′-localized elements, including the terminal stem–loop (3′ SL) together with cyclization sequence (3′ CS), the upstream of AUG region (3′ UAR) and the downstream of AUG region (3′ DAR), are crucial for the initiation of (−) strand, RNA-dependent RNA synthesis (2,5). These motifs are proposed to interact with their complementary elements positioned at the 5′ terminus, the 5′ CS, the 5′ UAR and the 5′ DAR, resulting in long-range RNA–RNA–mediated genome circularization (5,6,11). Following hybridization of the 5′ and 3′ termini, the DENV genome has been proposed to endure extensive rearrangements of both UTRs, opening of the 3′ SL to form an extended duplex with the 5′ UAR and formation of a double-stranded region via 5′ and 3′ CS interactions (12). As a result, the viral NS5 polymerase initially docked at the 5′ stem–loop A (SLA) would be relocated to the structurally reorganized 3′ terminus, allowing launch of (−) strand synthesis (6,11). Additional structural motifs of the 3′-UTR have also been shown to modulate DENV molecular processes. Phylogenetic comparisons have suggested that the tandem, almost identical dumbbell structures, designated 3′ and 5′ DB, might participate in regulation of RNA synthesis and translation (13–15). The leftmost hairpins of both DBs contain a set of identical five nucleotide motifs, referred to as TL1 and TL2 (5′-GCUGU-3′). The top loop (TL) regions have been suggested to pair with complementary motifs (PK2 and PK1, respectively) nested within A-rich sequences flanking both DBs (13,16). The TL1/PK2 and TL2/PK1 interactions would promote formation of two pseudoknots, which have been proposed to modulate both viral replication (15) and translation (8).

Current knowledge regarding the secondary structure of DENV 3′-UTR derives from folding algorithms and phylogenetic comparisons (8,13). With respect to the structure of 5′ terminal motifs, the majority of data originate from chemical or enzymatic probing of short RNA segments (12), often in the absence of their complementary partners (17). In this study, we have analyzed the interplay of these regions by solving the secondary structure of DENV 5′ and 3′ terminal regions in the context of a 719-nt subgenomic minigenome (hereafter referred as ‘DENV-MINI’) (18). We combined selective 2′-hydroxyl acylation analyzed by primer extension (SHAPE) with Pb2+ ion-induced hydrolysis and site-directed mutagenesis of DENV-MINI mutant RNAs to examine the previously proposed cis-acting RNA motifs and their potential binding partners, as well as identify long-range tertiary interactions between them. Our findings provide new insights into the secondary and tertiary interactions of DENV-MINI RNA and contribute to the understanding of viral RNA replication.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

DENV-MINI mutants

Construction of the plasmid encoding DENV-MINI RNA has been described previously (18). Mutants were generated by site-directed mutagenesis using the Agilent QuikChange Lightning Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Supplementary Table S1).

In vitro RNA synthesis

DNA templates for in vitro transcription were generated by PCR amplification of the plasmid DENV-MINI and the corresponding mutants, using primers listed in Supplementary Table S1. All PCR experiments were performed using Invitrogen Platinum® Taq DNA polymerase High Fidelity. Transcripts were synthesized with the Ambion T7-MEGAscript following the manufacturer’s protocol, and RNAs were purified from denaturating 8 M urea/5% polyacrylamide gels, followed by elution and ethanol precipitation. Purified RNAs were dissolved in sterile water and stored at −20°C.

Selective 2′-hydroxyl acylation analyzed by primer extension (SHAPE)

Twenty picomoles of RNA was heated at 90°C for 3 min and slowly cooled to 4°C. The volume was adjusted to 150 µl in a final buffer of 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0), 100 mM NaCl and 5 mM MgCl2. Samples were incubated at 37°C for 15 min. Folded RNA was divided into two equal portions (72 µl) treated with 8 µl of 30 mM N-methylisatoic anhydride (NMIA) in anhydrous dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (+) or DMSO alone (−). Tubes were incubated at 37°C for 50 min, and RNA was precipitated at −20°C with 60 ng/μl glycogen, 0.3 M sodium acetate (pH 5.2) and 3 volumes of cold ethanol. Precipitated RNA was collected by centrifugation, washed once in 70% ethanol and resuspended in 10 μl of water. Five picomoles of Cy5-labeled (for NMIA-modified samples) or Cy5.5-labeled (for unmodified samples) primer S720 or S440 (Supplementary Table S1) in 7 µl H2O was annealed to the RNA at 85°C for 1 min, 60°C for 5 min and 35°C for 5 min. RNA was reverse transcribed at 50°C for 20 min with 100 U reverse transcriptase (RT) (Invitrogen superscript III), 1× RT buffer (Invitrogen), 5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) and 500 mM dNTPs (Promega). RNA was hydrolyzed with 200 mM NaOH (4 M) for 5 min at 95°C, and reactions were neutralized with an equivalent volume of HCl (2 M). Sequencing ladders were prepared using the Epicentre cycle sequencing kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions and primers labeled with WellRed D2 and LicorIR-800 dyes. Modified and control samples were mixed with the sequencing ladders, precipitated as described earlier in the text, dried and resuspended in 40 ml of deionized formamide. Primer extension products were analyzed on a Beckman CEQ8000 Genetic Analysis Systems as described previously (19). Electropherograms were processed using the SHAPEfinder program, following the software developer’s protocol and included the required pre-calibration for matrixing and mobility shift for each set of primers as described (20,21). Briefly, the area under each negative peak was subtracted from that of the corresponding positive peak. The resulting peak area difference at each nucleotide position was then divided by the average of the highest 8% of peak area differences, calculated after discounting any results greater than the third quartile plus 1.5× the interquartile range. Normalized intensities were introduced into RNAstructure version 5.3 (22).

Pb2+ ion-induced cleavage

Before Pb2+ ion-induced cleavage, RNA transcripts (10 pmol) were subjected to refolding as described earlier in the text. A freshly prepared solution of Pb(OAc)2 was added to a final concentration of 0.5 mM, and the reaction mixtures were incubated for 10 min at room temperature (23). Reactions were quenched by adding an equal volume of 20 mM EDTA followed by ethanol precipitation. Cleavage sites were detected by primer extension as described earlier in the text (19).

Antisense interfered SHAPE

Locked nucleic acid (LNA)/DNA chimeras were ordered from Exiqon, the sequences of which are provided in Supplementary Table S1. Chimeras were added at 10-fold excess after folding. Samples were subsequently incubated at 37°C for 15 min before NMIA treatment (see earlier in the text). To quantify alterations induced by ai-oligonucleotides, raw data were processed as described earlier in the text. Tertiary interactions were introduced manually into RNAstructure version 5.3 generated models (22).

3D modeling of DENV-MINI RNA

The secondary structure of DENV-MINI RNA predicted by RNAstructure software version 5.3 (22) and chemical probing data from SHAPE (21) were used to generate 3D models for 474-nt DENV-MINI RNA by RNAComposer, version 1.0 (http://rnacomposer.cs.put.poznan.pl/). The quality of predicted models was evaluated using MolProbity tool (24). Where required, spatial positioning of RNA substructures were adjusted and the affected regions subjected to energy minimization using Discovery Studio v3.5 (Accelrys, San Diego, CA, USA).

RESULTS

Probing analysis of DENV-MINI RNA verifies the 5′–3′-UTRs long-range interactions and suggests a TL1/PK2 pseudoknot

SHAPE has been developed to study RNA secondary structure by examining backbone flexibility (directly related to the base pairing) at each nucleotide position via reactivity with a specific electrophilic reagent (21). We applied this technique to the in vitro-synthesized 719-nt subgenomic ‘minigenome’ RNA (DENV-MINI) template, which contains the 5′-terminal 226 nt, 42 nt from the C-terminal coding region of NS5, including the UAG termination codon, and the 451-nt 3′ terminus (18). Previous studies showed that this RNA molecule harbored essential cis-acting elements for efficient translation (25,26), as well as (−) strand RNA synthesis in vitro by either DENV2-infected cell lysates or purified RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRP) (27,28). DENV-MINI RNA was also used for secondary structure prediction analysis using the MPGAfold algorithm (29) to infer the structure–function role of the TLs and PKs regions in DENV replication and translation (8).

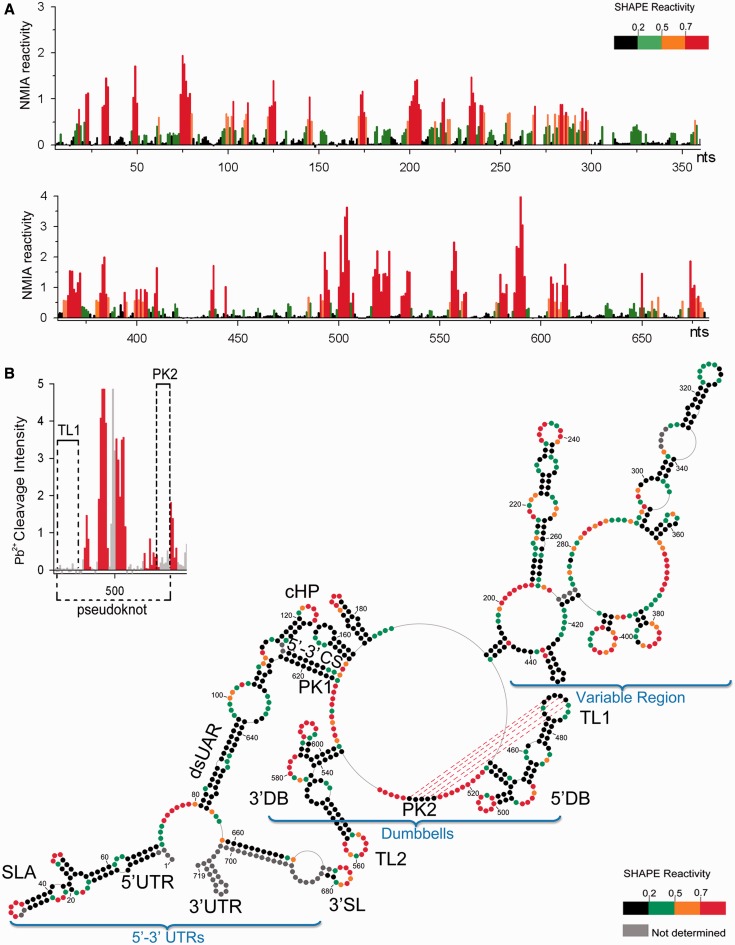

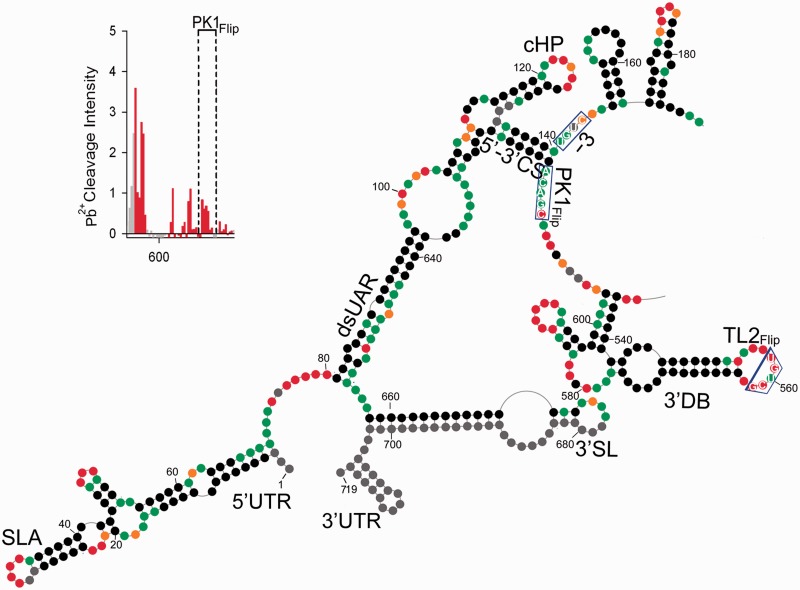

Reactivity of NMIA at each nucleotide position of DENV-MINI RNA is shown on Figure 1A and B and Supplementary Figure S1. The most reactive and thus least conformationally constrained residues have a reactivity >0.8 U and are depicted in red. Nucleotide positions with reactivity <0.2 U, indicative of fully base paired residues, are in black, whereas residues of intermediate reactivity are color-coded according to the key. Data shown are an average of at least three experiments.

Figure 1.

Secondary structure of the nucleotides 1–719 of DENV-MINI RNA. (A) Processed SHAPE reactivities of DENV-MINI RNA are presented as a function of nucleotide position. Red and orange notations are expected to fall in single-stranded regions, whereas bases indicated in black and green correspond predominantly to either double-stranded regions or putative tertiary interactions. (B) Three distinct DENV RNA domains have been annotated, namely, 5′–3′-UTRs, DBs and VR. Nucleotide positions are numbered every 20 nt. The abbreviations correspond to the following cis-acting RNA elements: UTR, untranslated region; SLA, stem–loop A; dsUAR, double-stranded upstream of AUG region; cHP, capsid hairpin; CS, cyclization sequences; DB, dumbbell; TL, top loop; SL, stem–loop. The pattern of Pb2+-induced hydrolysis obtained for interacting regions is indicated in the upper left insert.

Minimal free-energy modeling using SHAPE data as pseudo free-energy constraints is consistent with proposed 5′-UTR motifs in the context of DENV-MINI RNA (Figure 1B and Supplementary Figure S1) (6,17,30). Two regions that exhibit high sensitivity to NMIA modifications were located within the 5′ stem–loop A (SLA), A31–U34 and U48–A50, which corresponded to the TL and the side stem–loop (SSL), respectively. Three helical regions of 5′ SLA, U3–G9:C64–G70, C11–G15:A56–G61 and C24–A29:U35–G40, were insensitive to NMIA. The remainder of the reactive nucleotides were situated within the U62–U63 bulge and internal loops G17–A19 and G22–A23. Downstream of SLA, the oligoU tract spanning nt U71–U80 was predicted to be single-stranded. This region was followed by the unreactive double-stranded upstream of AUG region (dsUAR), formed via a long-range interaction between the 5′- and 3′-UTRs (nt A81–G96 and nt C638–U654). Here, the only reactive residues occupied the vicinity of bulge (C646), mismatch (G84) and the closing base pair of the helix. The internal loop enclosing the first AUG codon (nt A97–A104 and G631–C637) was predicted to be single-stranded followed by the double-stranded 6-nt long downstream of UAR region (DAR) containing reactive residues within the mismatch (A108) and the closing pairs of the helices. The capsid hairpin (cHP, A115–U133) (12), displayed an unreactive stem followed by a 7-nt reactive apical loop. As suggested by previous chemical probing studies, the 5′–3′ terminal interactions were mediated by base pairing between the 5′ and 3′ cyclization sequences, which formed 11-nt double-stranded cyclization region (CS) (U134–G144 and C614–A624) (12). Subsequently, two short hairpins that formed downstream of the 5′–3′ CS were found within the sequence of the 5′-end of the capsid protein gene. One contains a purine-rich and moderately reactive apical loop (A152–U159) and the other with a reactive 3-nt loop and A–C mismatch (G165–C185). Both hairpins were followed by 5-nt helical region (A190–U194 and A444–U448), which provided additional linkage between the 5′ and 3′ termini.

With regard to the 3′-UTR, SHAPE provided information on the 3′ SL structure, obscured only at the extreme 3′ terminus because of the presence of hybridized primer (Figure 1B and Supplementary Figure S1). The 3′ SL displayed NMIA sensitivity at the apical loop (A674–C680) and insensitivity at its leftmost side. The fact that this large 79-nt stem–loop was followed with reactive stretch of 3 nt (C655–U657) and unreactive dsUAR region (nucleotides A81–G96 and nucleotides C638–U654), enforced the proposed conformation. Previous phylogenetic comparative studies suggested that the 3′-UTR enclosed two almost identical DBs that might assume a pseudoknot conformation with their downstream complementary regions (13,16). SHAPE data confirmed the presence of both, and in addition provided detailed insight into their secondary structure. The 3′ DB contained a 6-bp unreactive stem (U536–G541 and C598–A603) and two hairpins on opposing ends (G547–U571 and G584–C597). The apical loop of the leftmost hairpin incorporated the highly reactive TL2 sequence (G558–U562). The reactivity of TL2, combined with the fact that its downstream complementary partner PK1 (A613–C617) was involved in formation of 5′–3′ CS region, would likely prevent the previously suggested TL2/PK1 pseudoknot interaction (13,16). Regarding the 5′ DB, it likewise contained an unreactive stem (G449–G454 and C511–C516) and two hairpins on opposing ends (C462–G482 and G497–C510). Here, however, the apical loop of the leftmost hairpin incorporating the TL1 sequence (G467–G477), although predicted to be single-stranded, harbored mainly unreactive nucleotides. The fact that its complementary partner PK2 was likewise unreactive and enclosed within single-stranded loop (G526–C530) was strongly suggestive of a TL1/PK2 base pairing interaction (Figure 2) (13,16). In addition, both DBs comprised reactive bulges (A491–C496 and A578–A583) and moderately NMIA-sensitive purine-rich internal loops. One of the internal loops of the 3′ DB (G572–A575) was insensitive to modification as it contained a -GGAA- motif. Such -GNRA- tetraloops represent a unique fold, which include a trans sugar edge/Hoogsteen edge G∙A pair between the first and the last residues, a hydrogen bond between the 2′-OH of G and the N7 of A and 3′ stacking of all tetraloop bases except the G. This architecture would account for lack of reactivity towards NMIA (31).

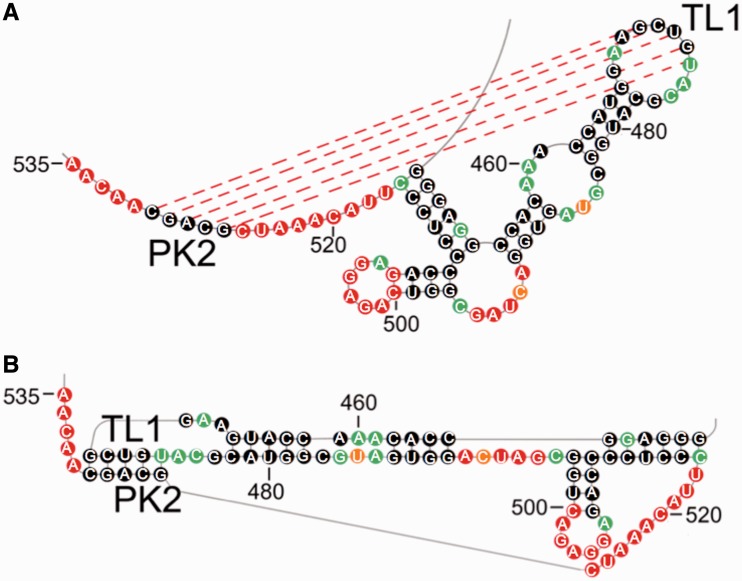

Figure 2.

TL1/PK2 pseudoknot interaction in DENV-MINI RNA. (A) SHAPE-predicted hairpin-type pseudoknot interaction comprises two helical regions, including base paring between PK2 (G526–C530) and TL1 residues (G470–U474), as well as the stem of the leftmost hairpin (C462–G466 and C478–G482), and three single-stranded loops: A468–G470, U474–C476 and C516–C525. (B) The 2D map of TL1/PK2 interaction forming H-type pseudoknot generated by PseudoViewer3 (32).

The region upstream of the DBs is often referred to as the variable region (VR), as its sequence differs between DENV serotypes (Figure 1B and Supplementary Figure S1) (33). Our probing analysis indicated its propensity to form long single-stranded stretches (A274–A291, U364–A376, G418–C424 and U439–A443). One of the loops (U439–A443), composed almost exclusively of adenine residues, was mainly NMIA unreactive. It was shown previously that consecutive adenine bases in single-stranded regions are often involved in stacking interactions, which would account for their inaccessibility towards NMIA modification (34,35). The 3′-UTR region also contained two stable tetraloops (C352–G363 and C425–G438). As expected, the -GNRA- tetraloop (C425–G438), restricted by extensive stacking and hydrogen-bonding interactions, was NMIA-insensitive (31). On the other hand, the -CAAG- tetraloop (C352–G363) behaved differently. Here, only its GC residues showed little reactivity, which could be interpreted as formation of an intraloop G∙C base pair, whereas its AA residues were reactive. The apical loops of two other hairpins (G377–C392 and G396–C412) showed strong NMIA reactivity. Also, an extended hairpin containing internal asymmetric loop (A296–U301 and U345–G346), a bulge (C307–A313) and A-rich, moderately reactive apical loop (A323–A331) was predicted to form between nucleotides G292–C350. Another long hairpin (U206–A267) with a reactive apical loop (A233–A241) and two reactive internal loops (G218–A222 and C252–A256; A227–A229 and G245–A247) enclosed a linker sequence that stretched from A227–G268.

Our secondary structure determination of DENV-MINI RNA was furthermore validated by single-strand–specific Pb2+ ion-induced hydrolysis (23) (Supplementary Figure S2). The observed cleavage pattern correlated with SHAPE-predicted single-stranded regions. The 5′-UTR regions highly sensitive to Pb2+ cleavage included the vicinity of SLA internal loop (C14–G15), SLA SSL (U48–A49) and the polyU tract (U71–U80). The SLA TL (C30–U34), as well as the apical loop of cHP (A121–A127), was hydrolyzed weakly, agreeing with previous studies showing that in most cases, bulges and internal loops were more readily cleaved with Pb2+ ions than apical loops (23). The 5′–3′ CS (U134–G144) and dsUAR (A88–G96) were resistant to cleavage, as they were predicted to be double-stranded. In addition, the two hairpins formed within the sequence of the 5′-end of the capsid protein gene (A152–G153 and A174–C175) were moderately sensitive to hydrolysis, whereas the following single-stranded region was hydrolyzed readily (C199–A205).

Pb2+ ions moderately cleaved some of single-stranded stretches of the 3′-UTR (A277–C289), whereas others, particularly the A-rich ones, had isolated cleavage points (A369 and C375) or were resistant to hydrolysis (U439–A443) (Supplementary Figure S2). The two tetraloops of the 3′-UTR (C352–G363 and C425–G438) were resistant to hydrolysis, consistent with previous studies, indicating that tetraloops showed little or no Pb2+-induced hydrolysis because of extensive stacking interactions (36). The apices of other hairpins (G325–A327, A384–C385 and G402–U408) were moderately reactive. The most pronounced Pb2+-induced hydrolysis occurred within the apex of the 3′ SL (C673–C675), the internal loops of DBs (A491–G495 and C579–G582) and the loops of their rightmost hairpins (U500–G505 and A588–G592). Lack of Pb2+ cleavage within TL1 and its putative complementary partner PK2 was again suggestive of their base pairing interaction (Figure 1B insert and Supplementary Figure S2). In contrast, TL2 (G555–U562) was hydrolyzed readily, whereas its PK1 partner, predicted to be involved in the double-stranded 5′–3′ CS interaction, was resistant to cleavage.

Antisense-interfered SHAPE data support a novel TL1/PK2 pseudoknot interaction

To examine the TL1/PK2 tertiary interaction (13,16), antisense-interfered SHAPE (aiSHAPE) strategy has been applied (37). In this method, displacement of one strand of an RNA duplex by hybridizing an antisense oligonucleotide would disrupt long-distance interactions and would be characterized by enhanced NMIA sensitivity of the displaced nucleotides (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Structural responses of the TL1/PK2 pseudoknot motif to antisense oligomers. (A) aiSHAPE principal. Hybridization of an interfering oligonucleotide (green) to one partner of the proposed RNA duplex increases acylation sensitivity of its base-paired counterpart. (B) Influence of LNA/DNA oligonucleotide (orange) hybridized to PK2 on chemical reactivity of TL1 residues. (C) The effect of LNA 1B hybridization to TL1 loop on acylation of PK2 nucleotides. The gray residues represent the formation of an extensive stop during reverse transcription at the place of LNA hybridization. The native traces (red) are compared with antisense-interfered DENV-MINI RNA (violet). Nucleotide positions exhibiting increased NMIA reactivity in the presence of given LNA are distinguished by orange brackets.

Two chimeric LNA/DNA heptanucleotides were hybridized to either TL1 or PK2 regions to disrupt the potential base pairing interaction with their respective partner (Supplementary Table S1). LNA/DNA heptanucleotide 1A was complementary to the single-stranded region A523–G529, including PK2, whereas LNA/DNA heptanucleotide 1B was complementary to the loop of the leftmost hairpin of the 5′ DB, C471–G477 and included TL1 region.

Hybridization of LNA/DNA 1A enhanced reactivity within TL1 residues (Figure 3B and Supplementary Figure S3). Median reactivities for nucleotides A468–G473 were 0.27, whereas the corresponding values for DENV-MINI were 0.05. In addition, LNA/DNA 1A hybridization formed an extensive barrier to reverse transcription (A503–G529), supporting the specificity of our aiSHAPE strategy (Supplementary Figure S3). Hybridization of LNA/DNA 1B increased the median reactivities of the PK2 residues G526–C530 to 0.38, whereas the corresponding values for DENV-MINI were 0.05 (Figure 3C and Supplementary Figure S3). Here, again, the specificity of LNA/DNA 1B hybridization to TL1 was substantiated by formation of an extensive stop during reverse transcription (C463–G477) (Supplementary Figure S3). In both cases, NMIA reactivity profiles for the entire 719-nt DENV-MINI indicated minor ‘off site’ changes mainly occurring within the DB structures, whereas the 5′ portion of the DENV-MINI was not significantly affected (Supplementary Figure S3). Despite this, the RNAstructure algorithm, when provided with pseudo energy constrains retrieved from LNA experiments, predicted the identical DENV-MINI secondary structure (data not shown). However, we cannot exclude the possibility that global DENV-MINI RNA folding might be altered by LNAs hybridization on a higher level that chemical probing cannot address. Despite these minor discrepancies, aiSHAPE data lend further credence to TL1/PK2 pseudoknot (Figure 2).

Mutations within PK2 region disrupt TL1/PK2 pseudoknot

Previously, Manzano et al. (8) suggested putative roles of the TL/PK interactions in DENV replication. To disrupt potential TL1/PK2 and TL2/PK1 base pairing, they introduced point mutations by ‘flipping’ the corresponding sequences (TLs 5′-GCUGU-3′→5′-UGUCG-3′ and PKs 5′-GCAGC-3′→5′-CGACG-3) in the context of the DENV2 replicon expressing Rluc. This strategy showed that the PK2Flip mutation attenuated DENV Rluc replication, but not translation, suggesting that PK2 region is crucial for viral RNA synthesis. As the DENV2 Rluc replicon encompassed the same cis-acting regulatory sequences as the DENV-MINI RNA used in our studies, we next sought to address the structure–function relation of PK2 mutations in the context of DENV-MINI RNA.

SHAPE analysis of PK2Flip DENV-MINI mutant RNA indicated major reactivity changes within the 5′ DB structure (Figure 4 and Supplementary Figures S4 and S5). The apical loop of the TL1-containing hairpin was rendered NMIA-sensitive with median reactivities for G470–U474 of 0.55, whereas the corresponding values for WT DENV-MINI were 0.05. The apex of the rightmost hairpin exhibited lower reactivity for residues G502–A506. In addition, the ‘flipping’ mutation of PK2 increased its susceptibility to acylation (C526–G530) validating disrupted TL1/PK2 base pairing. Other regions did not exhibit secondary structure rearrangements. Thus, data of Figure 4 and all subsequent illustrations representing RNA structures of DENV-MINI mutants present only the affected RNA motifs.

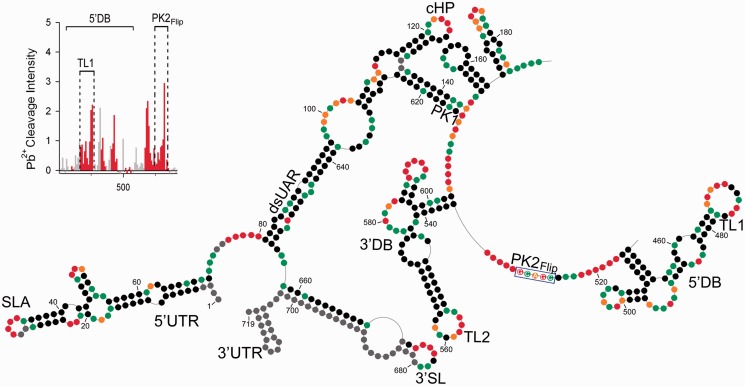

Figure 4.

Chemical probing of PK2Flip mutant RNA. The description of the scheme follows the convention of the Figure 1 legend. The flipping mutation within PK2 is marked by a blue rectangle. The insert in the left top corner represents increased Pb2+-induced hydrolysis within PK2 and TL1 regions.

Single-strand–specific Pb2+-induced cleavage of the PK2Flip construct verified that the ‘flipping’ mutation released both TL1 and PK2 from a base pairing interaction, as both regions were now strongly susceptible to hydrolysis (Figure 4 insert and Supplementary Figure S6). In addition, the apex of the rightmost hairpin showed lowered cleavage intensity as compared with DENV-MINI RNA (Supplementary Figure S2).

Mutations within PK1 region impair 5′–3′ terminal long-range interactions

Previous in vivo studies using DENV2 Renilla luciferase (Rluc) reporter replicon in BHK21 cells have shown that the ‘flipping’ mutation of PK1 severely reduced viral replication, whereas mutating both TL2 and PK1 to maintain their base pairing generated even more severe phenotype (8). Also, introducing compensatory mutations in the 5′ CS (mutant TL2Flip PK1Flip-3) to restore base pairing between the 5′–3′ CS failed to improve replication, from which strong structure- and sequence-specific requirements for TL2 and PK1 function in DENV RNA replication have been proposed (8). Consequently, we sought to investigate the structure–function relation of both regions in the context of DENV-MINI RNA.

The NMIA sensitivity profile of PK1Flip mutant indicated extensive alternations within the 5′- and 3′-UTRs (Figure 5 and Supplementary Figures S7 and S8). The 5′ UAR no longer formed a double-stranded region, but instead, it became a part of the novel SLB hairpin (G70–C105) with a reactive apical loop (G86–G89) and internal loops (U73–A77 and G99–U102). The 5′ DAR region, previously double-stranded in DENV-MINI, rearranged into a reactive single-stranded loop (C105–G110). In addition, the PK1 ‘flipping’ mutation abolished base pairing between 5′ and 3′ CS, disrupting the previous double-stranded 5′–3′ CS. The 5′ CS (C135–G144) now formed a reactive single-stranded region downstream of cHP, whereas the 3′ CS (C613–U622) and the ‘flipped’ PK1 region (C613–A617) comprised a reactive loop downstream of the 3′ DB. In addition, the two hairpins previously formed within the sequence of the 5′-end of the capsid protein gene were fused into an extended hairpin (G153–C197) with a weakly reactive internal loop (A158–G163 and A187–A192) and an A–C mismatch.

Figure 5.

Chemical probing of PK1Flip mutant RNA. The description of the scheme follows the convention of Figure 1 legend. The flipping mutation within PK1 region is marked by blue rectangle. The insert in the left top corner represents increased Pb2+-induced hydrolysis within ‘flipped’ PK1 residues and the novel motif, stem–loop B (SLB).

Further alternations were noted within the 3′-UTR, where the 3′ SL became a part of extended hairpin (A641–U719) proceeded by short hairpin (sHP) (C627–G640) containing moderately reactive GNn/RA hexaloop (Figure 5 and Supplementary Figures S7 and S8) (23,38). The sHP was shown previously to fold locally in the linear conformation of the DENV RNA, governing the balance between alternative DENV RNA structures (39). The 3′ UAR, which no longer interacts with the 5′ UAR, now formed both the rightmost side of the sHP and the leftmost side of the 3′ SL (C638–U650), whereas the 3′ DAR became a leftmost part of the sHP (C625–G630). As the ‘flipping’ PK1 mutation affects the secondary structure of neither the 3′ nor the 5′ DB, this result likely ruled out the existence of the previously proposed TL2/PK1 pseudoknot interaction (13,16). The VR region was not affected (C232–U448), with the exception of a short helical region (A190–U194 and A443–U448) that in DENV-MINI RNA linked both DBs and VR domains, and now was predicted to be single-stranded and NMIA reactive.

Pb2+ ion-induced cleavage pattern for mutant PK1Flip substantiated the SHAPE-predicted alterations of RNA secondary structure (Figure 5 insert and Supplementary Figure S9). Residues of SLB apical loop (A85–A88), as well as internal loop (U73–A78 and U99–U100), were readily hydrolyzed, whereas the A78–G84:U91–U98 stem was not cleaved. Also, the DAR region (A107–C109) and 5′ CS (A137–C142) were susceptible to cleavage, which agreed with their single-stranded character. With regard to the 3′-UTR, moderate hydrolysis was noted within the stem of the extended 3′ SL, as it contained numerous bulges and loops that relaxed its overall stability. Pb2+ cleavage was most pronounced within the apex of the 3′ SL (A674–C675). The 3′ CS region containing the flipped PK1 exhibited single-cleavage points (A604, A605 and A620), whereas the apex of sHP (GNn/RA hexaloop) showed no susceptibility to hydrolysis. Overall, the PK1 ‘flipping’ mutation disrupted the 5′–3′ terminal interactions by affecting the conformation of RNA motifs on both termini.

Regarding the TL2FlipPK1Flip mutant, the addition of ‘flipping’ mutations within TL2 was designed to preserve complementarity between TL2 and PK1. Also, SHAPE-assisted prediction of RNA folding showed that PK1 was embedded in single-stranded region available for pairing with TL2. It was suggested previously that releasing PK1 from the 5′–3′ CS region provides the switch between the translation and replication mode of the DENV genome by rendering PK1 available for a pseudoknot interaction with TL2 (13). In our study, the RNA secondary structure predicted for TL2FlipPK1Flip mutant resembled the structure of the PK1Flip mutant (Supplementary Figures S10 and S11). Residues of neither PK1 nor TL2 displayed a change in NMIA sensitivity, contradicting the implication that TL2 is involved in long-range interactions with PK1 in the context of DENV-MINI construct. Pb2+-induced hydrolysis of TL2FlipPK1Flip mutant provided a pattern of cleavage comparable with that obtained for the PK1Flip mutant (Supplementary Figure S12), the only difference being lower intensity of hydrolysis within the internal loops and rightmost apical loops of both DBs.

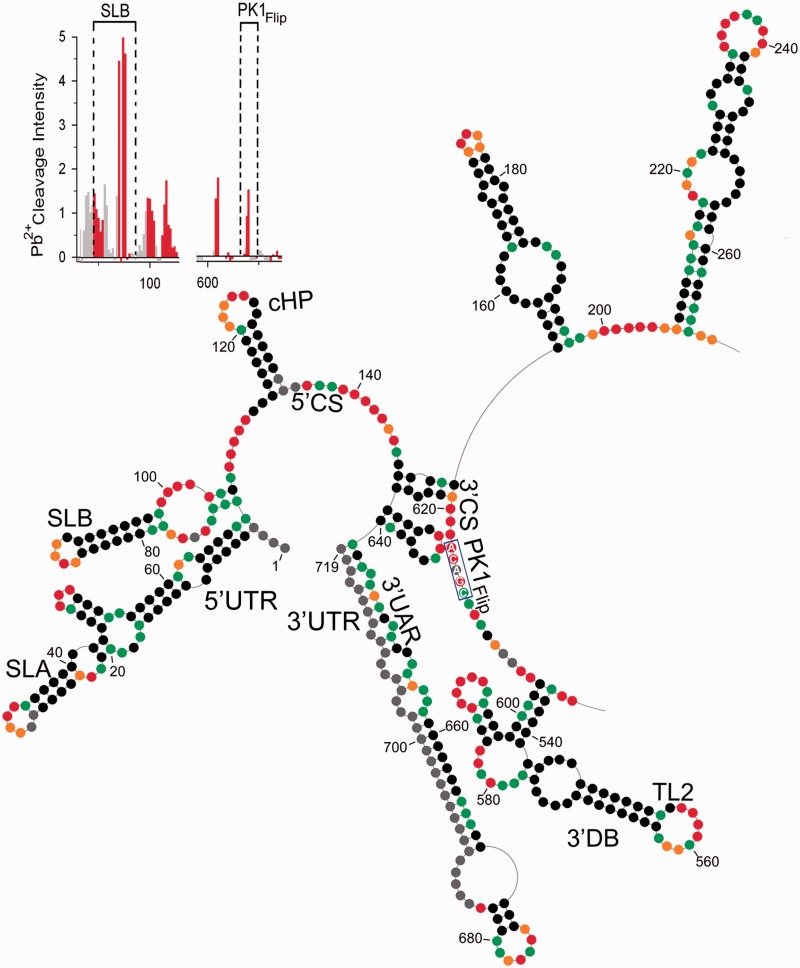

We also investigated how introducing 3-nt compensatory mutations within the 5′ CS (U141–C144) to restore the 5′–3′ CS in the presence of ‘flipped’ TL2 and PK1 affected DENV MINI RNA structure. SHAPE analysis of mutant TL2FlipPK1Flip-3 predicted almost complete reversion to the wild-type secondary structure (Figure 6 and Supplementary Figures S13 and S14). The only rearrangement occurred within the 5′–3′ CS region, which was shortened from 11-nt helical region to 6-nt stem (C135–U140 and A624–A618), releasing PK1 (C613–A617) and compensatory residues into single-stranded loops. Thus, the complementarity and single-strand character of both the downstream component of 5′ CS and PK1 proved insufficient to maintain their base pairing interaction. Pb2+-induced hydrolysis of TL2FlipPK1Flip-3 mutant (Figure 6 insert and Supplementary Figure 15) indicated moderate cleavage within the region carrying compensatory mutations, as well as within PK1 (A615–C616).

Figure 6.

Chemical probing of TL2FlipPK1Flip-3mutant RNA. The description of the scheme follows the convention of Figure 1 legend. The 3-nt compensatory mutations introduced within 5′ CS, the ‘flipping’ mutations within PK1 and TL2 region are marked by blue rectangles and trapezoid. The insert in the left top corner represents the pattern of increased Pb2+-induced hydrolysis within ‘flipped’ PK1 and compensatory residues.

Collectively, chemical probing analysis of DENV-MINI mutants supported the notion that, rather then being involved in the TL2/PK1 pseudoknot interaction, the structure- and sequence-specific composition of the PK1 region is essential for sustaining the correct conformation of the 5′ and 3′ terminal motifs necessary for 5′–3′ terminal RNA–RNA interaction.

3D modeling of DENV-MINI TL1/PK2 pseudoknot interactions

A 3D structural model of the DENV-MINI RNA was generated using RNAComposer, a fully automated server that predicts 3D structural models from RNA secondary structure (40) (Figure 7). As the server does not accept sequences longer than 500 nt, a 474-nt derivative sequence was created by deleting the VR domain and closing the remaining short helical region (A190–U194 and A443–U448) with a -GAGA- tetraloop. A dot-bracket notation generated by the RNAstructure software was adjusted to account for this internal deletion, as well as the predicted TL1/PK2 pseudoknot, and subsequently provided to RNAComposer. Ten 3D RNA models were generated and analyzed, taking into account their secondary structure topology, sequence homology, structure resolution and free energy. In addition, the quality of predicted models was evaluated using the MolProbity tool (24). The best of these models was manually adjusted to correct for an unlikely fold within PK1, and the affected regions were subjected to energy minimization (Accelrys Discovery Studio v3.5) to create the structure of Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Proposed 3D model of truncated DENV-MINI RNA. The internally deleted DENV-MINI RNA is depicted (A) in its entirety or (B) highlighting the proximal 5′- and 3′-UTRs. Specific RNA domains are color-coded as shown in the key. The cis-acting motifs are labeled as follows: SLA TL, stem–loop A top loop; SLA SSL, stem–loop A side stem–loop; 3′ SL, 3′ stem–loop; dsUAR, double-stranded upstream of AUG region; PK, pseudoknot; TL, top loop. For clarity, the remainder of the RNA molecule is colored in gray.

The model shows close association of the 5′- and 3′-UTRs (Figure 7A and B), in agreement with previous studies, suggesting that efficient transfer of RNA-dependent RNA-polymerase from the 5′ SLA to the 3′ SL motif is essential for initiation of (−) strand RNA synthesis (12, 17). In addition, positioning of the hybridized 5′–3′ termini and the TL1/PK2 pseudoknot on opposite termini of the DENV-MINI RNA is consistent with the two domains playing independent structural/regulatory roles in DENV replication. TL2 of the 3′ DB is likewise spatially separated from other structural motifs, suggesting a functional role for TL2 that does not involve interactions with other RNA elements in the context. The 3′ DB itself is linked to adjacent segments of the DENV-MINI RNA by relatively long, presumably flexible segments of single-stranded RNA. It is conceivable that a second TL2/PK1 pseudoknot could be formed by rotation of the 3′ DB motif, thereby bringing TL2 into proximity with PK1. However, such a rearrangement would also require partial dissolution of the hybridized 5′–3′ termini. It is important to note, however, that there is no evidence that base pairing between TL2 and PK1 occurs in the DENV-MINI RNA in vitro. In general, although caution must be exercised in interpreting these 3D structural data, the model presented here serves to provide plausible insights into how RNA substructures may interact during DENV replication.

DISCUSSION

Following infection, the (+)-stranded DENV RNA must serve as a template for replication, an mRNA for translation and a substrate for encapsidation. The function(s) assumed by these RNAs are dictated in part by the specific local and long-range RNA interactions investigated in the present study. Our combined SHAPE, aiSHAPE and Pb2+-induced cleavage analysis of the DENV-MINI RNA establish the existence of multiple motifs required for initiation of (−) strand RNA synthesis (Figure 1B and Supplementary Figure S1). The presence of the 5′ SLA, demonstrated crucial for initial binding of RdRp (6,17), the single-stranded polyU tract providing the flexibility to the 5′-UTR (17), together with the rearrangements occurring within 3′ SL (17,30), established replication competency of DENV-MINI RNA (Figure 1B and Supplementary Figure S1). Our results have experimentally verified long-range interactions between the 5′ and 3′ terminal regions, which involved hybridization between (i) 5′–3′ CS, previously demonstrated to initiate the 5′–3′ long range RNA–RNA hybridization (5,15), (ii) the 5′–3′ UAR, required for the correct orientation of the SLA with respect to the 3′ end (30) and (iii) 5′–3′ DAR, extending the CS-initiated 5′–3′ interaction (11). We have predicted additional regulatory motifs that might contribute to the overall functionality of DENV-MINI RNA. Probing analysis identified tandem DBs spaced by A-rich single-stranded regions in the 3′-UTR, as well as internal loops and hairpins with embedded GNRA/GNRA-like motifs within the VR domain (Figure 1B and Supplementary Figure S1). These elements may represent candidate assembly sites for proteins, as previous studies identified several host factors that not only bind to DENV UTRs but also actively participate in regulation of replication and translation efficiency (41–44). In addition, -GNRA- tetraloops could act as ‘anchors’ by interacting in a sequence-specific manner with motifs at distant locations along the molecule to enhance RNA self-folding (45,46).

We have provided here novel insight into tertiary interactions that exist within the DB structures. Previous phylogenetic comparison of four sero-groups of flaviviruses suggested formation of two pseudoknots, TL2/PK1 and TL1/PK2, involving base pairing between the DBs TLs and the downstream complementary PK regions (13). These authors suggested that the single-base pair difference (A–G), distinguishing PK2 and PK1, conserved in all DENV strains, must have a functional reason to differentiate between both motifs (13). Manzano et al. (8) also indicated dissimilar functional roles of TL2/PK1 and TL1/PK2 in DENV replication and translation.

Our SHAPE-directed probing implied that the base pairing interaction between TL1 and PK2 formed the core of an extended, H-type pseudoknot, as both regions, even though embedded within single-stranded loops, contained unreactive residues (Figures 1B and 2). Also, both sequences were resistant to the complementary strategy of Pb2+-induced hydrolysis, supporting their potential base pairing interactions (Figure 1B insert and Supplementary Figure S2). aiSHAPE lends further credence to TL1/PK2 tertiary interactions (Figure 3 and Supplementary Figure S3), as outcompeting one base pairing partner increased reactivity of the other and vice versa. Moreover, SHAPE analysis of the PK2Flip mutant indicated a major increase in NMIA reactivity of TL1 and PK2 nucleotides, validating disruption of the TL1/PK2 base pairing interaction (Figure 4 and Supplementary Figures S4 and S5). Consequently, we propose that in the context of DENV-MINI RNA, the TL1 loop of the 5′ DB is involved in hairpin-type (H-type) pseudoknot interactions with the downstream PK2 region (Figure 2) (47). This pseudoknot was predicted to have two helical regions, including base paring between PK2 (G526–C530) and TL1 residues (G470–U474), as well as the stem of the leftmost hairpin (C462–G466 and C478–G482), and three single-stranded loops: A468–G470, U474–C476 and C516–C525 (Figure 2B).

We have also provided a 3D model of the TL1/PK2 interaction using the recently reported program RNAComposer (40). As noted in Figure 7, the hybridized 5′–3′ termini and the TL1/PK2 pseudoknot are located on opposite ends of the DENV-MINI RNA, suggesting an independent structural/regulatory character. Also, the fact that hybridization of LNA/DNA chimeras to either TL1 or PK2 failed to induce extensive structural changes within the interacting 5′–3′ termini (Supplementary Figure S3) suggests the TL1/PK2 pseudoknot might indeed function as an autonomous element. In addition, TL2 of the 3′ DB is spatially separated from other structural domains and linked to adjacent segments of the DENV-MINI RNA by relatively long single-stranded regions. It is possible that a second TL2/PK1 pseudoknot could be formed by rotation of the 3′ DB, thereby bringing TL2 into proximity with PK1. However, such a rearrangement would also entail partial dissolution of the hybridized 5′–3′ termini and perhaps even the TL1/PK2 interaction, such as might occur in the presence of viral proteins and/or host factors, or in the event the 5′ terminal portion of the genome has been removed by ribonucleases (10) or is sequestered during translation. A similar hypothesis was proposed based on MPGAfold-directed secondary structure prediction of DENV MINI RNA, which indicated differences in the folding behavior of the two DBs (8). In the lack of the 5′–3′ communication, it was proposed that TL2 could be available to bind PK1 in the 3′ DB to form the putative TL2/PK1 pseudoknot (8).

Pseudoknots are associated with a remarkably diverse range of biological activities, including translational control via internal ribosome entry site (48,49), ribosomal frameshifting (50,51), tRNA mimicry (47,52–54) and temporal control of the termination of translation and initiation of genome replication (55). It has been shown that ‘flipping’ of PK2 in the context of luciferase-based DENV2 replicon did not affect translation, but disrupted replication (8), from which we conclude that the TL1/PK2 pseudoknot participates in regulation of DENV RNA synthesis. It is also possible that the TL1/PK2 pseudoknot might create a critical recognition element for host proteins. Supporting this notion, pseudoknots have been shown to cause distortion of A-form helices, creating a bend in the complex to provide a recognition site for ligands (56). Also, it was shown that DEAD-box RNA helicase (DDX6) binds to both DBs and their corresponding PKs regions (43). These authors suggested that the putative pseudoknots might provide assembly sites for DDX6, and that proper assembly of this protein had functional consequences for DENV replication.

Our combined probing and mutational analysis also addressed the role of PK1 in the DENV-MINI RNA secondary structure. The ‘flipping’ mutation introduced into PK1 significantly rearranged the conformation of the 5′- and 3′-UTRs (Figure 5 and Supplementary Figures S7, S8 and S9). The 5′ and 3′ CS became single-stranded, whereas the UAR and DAR, previously required for 5′–3′ communication, became involved in formation of the 5′ SLB, the 3′ sHP and an extended 3′ SL motif. The presence of 5′ SLB was proposed as specific for the linear conformation of DENV RNA (39), reducing the ability of the 5′ UAR to hybridize to the 3′ partner (12). In addition, the sHP was suggested to fold locally in the linear conformation of DENV RNA (39). Although its function is uncertain, the sequences within the sHP were proposed to regulate the equilibrium between the DENV RNA alternative conformations for organizing multiple functions of the viral genome.

SHAPE-directed prediction of RNA folding indicated similar structure rearrangements for the TL2FlipPK1Flip mutant RNA (Supplementary Figures S10–S12), suggesting PK1 is mostly responsible for correct long-range communication between the 5′ and 3′ terminal regions. Even the presence of compensatory mutations within 5′ CS (TL2FlipPK1Flip-3 mutant) to restore base pairing with PK1 (Figure 6 and Supplementary Figures S13–S15) did not entirely reinstate the secondary structure of DENV-MINI RNA. Previous studies using DENV-MINI RNA as templates in in vitro RdRp assays have shown that replication of PK1Flip, TL2FlipPK1Flip mutants was significantly affected, supporting the importance of the 5′–3′ CS interaction for RNA synthesis (8). However, the introduction of compensatory mutations at the 5′ CS in DENV-MINI TL2FlipPK1Flip-3 mutant restored replication to nearly wild-type level. This was in contrast to the effects of the PK1 ‘flipping’ mutations on replication of luciferase-based DENV2 in BHK-21 cells, which showed essentially no replication (8). Related studies using luciferase containing Dengue virus (15), Kunjin virus (57) and West Nile virus replicons (58) carrying point mutations at the 3′ CS are consistent with our observations. In all cases, the altered sequence of 3′ CS attenuated replication, even when mutations were compensated at the 5′ CS. Also, a mutation introduced into the 3′ CS extending the region of complementarity between 5′–3′ CS by one nucleotide was shown to negatively affect replication kinetics of the subgenomic DENV reporter replicon (59). Apparently, not only the secondary structure of 5′–3′ CS region but also its sequence composition governs the efficiency of RNA synthesis.

In addition, the TL2FlipPK1Flip mutant (Supplementary Figure S10) provided insight into the second, previously proposed TL2/PK1 pseudoknot (13,16). It was suggested previously that PK1 could modulate DENV genome cyclization via either a 5′–3′ CS interaction or by base pairing with TL2 (13,25). Also, studies showed that the long-distance 5′–3′ CS complementarity interferes with efficient translation of DENV2 luciferase (LUC) reporter system in Vero cells (25). It was suggested that the 5′–3′ CS interaction may play role in regulating the transition from the translation to the replication phase of the infection. Thus, we expected that release of PK1 from 5′–3′ CS together with the conserved complementarity between both partners, would support formation of TL2/PK1 pseudoknot. SHAPE analysis, however, indicated no reactivity change within ‘flipped’ TL2 and PK1 (Supplementary Figures S10 and S11). As the addition of ‘flipping’ mutations within TL2 did not cause any further structural rearrangements compared with PK1Flip mutant (compare Figure 5 and Supplementary Figures S7 and S8), this would dismiss the involvement of TL2 in tertiary interactions. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that in vivo a TL2/PK1 interaction could be stabilized by participation of host or viral factors for the purpose of other molecular processes, i.e. translation, before the 5′–3′ CS interaction. Indeed, it has been proposed that the viral NS3 helicase can modulate the folding of cis-acting RNA elements via dual RNA unwinding/annealing activities, providing the switch between alternative conformations of the DENV genome (38,60).

Considering that DENV RNA must assume alternative conformations (39) to fulfill a continuous need to function as mRNA, the replication template, as well as the viral genome, we must bear in mind that the structure reported here may be only partially representative of the in vivo viral RNA population. Further studies will address folding of DENV RNA at different stage of viral life cycle to understand the mechanisms that modulate multifunctionality of viral RNA and, as a result, promote rational design of live attenuated vaccines and/or antiviral therapeutics.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online: Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Figures 1–15.

FUNDING

Intramural Research Program (IRP) of the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services ( to J.S.S., J.W.R., B.A.S. and S.L.G.); National Institutes of Health [R01AI070791-03S1, U01-AI082068 and R011R01AI087856 to T.T. and R.P.]. Funding for open access charge: National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- 1.Miller WA, White KA. Long-distance RNA-RNA interactions in plant virus gene expression and replication. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2006;44:447–467. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.44.070505.143353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alvarez DE, Lodeiro MF, Luduena SJ, Pietrasanta LI, Gamarnik AV. Long-range RNA-RNA interactions circularize the dengue virus genome. J. Virol. 2005;79:6631–6643. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.11.6631-6643.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Song BH, Yun SI, Choi YJ, Kim JM, Lee CH, Lee YM. A complex RNA motif defined by three discontinuous 5-nucleotide-long strands is essential for Flavivirus RNA replication. RNA. 2008;14:1791–1813. doi: 10.1261/rna.993608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu B, Pogany J, Na H, Nicholson BL, Nagy PD, White KA. A discontinuous RNA platform mediates RNA virus replication: building an integrated model for RNA-based regulation of viral processes. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000323. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Villordo SM, Gamarnik AV. Genome cyclization as strategy for flavivirus RNA replication. Virus Res. 2009;139:230–239. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2008.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Filomatori CV, Iglesias NG, Villordo SM, Alvarez DE, Gamarnik AV. RNA sequences and structures required for the recruitment and activity of the dengue virus polymerase. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:6929–6939. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.162289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wei Y, Qin C, Jiang T, Li X, Zhao H, Liu Z, Deng Y, Liu R, Chen S, Yu M, et al. Translational regulation by the 3′ untranslated region of the dengue type 2 virus genome. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2009;81:817–824. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2009.08-0595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manzano M, Reichert ED, Polo S, Falgout B, Kasprzak W, Shapiro BA, Padmanabhan R. Identification of cis-acting elements in the 3′-untranslated region of the dengue virus type 2 RNA that modulate translation and replication. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:22521–22534. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.234302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pijlman GP, Funk A, Kondratieva N, Leung J, Torres S, van der Aa L, Liu WJ, Palmenberg AC, Shi PY, Hall RA, et al. A highly structured, nuclease-resistant, noncoding RNA produced by flaviviruses is required for pathogenicity. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;4:579–591. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silva PA, Pereira CF, Dalebout TJ, Spaan WJ, Bredenbeek PJ. An RNA pseudoknot is required for production of yellow fever virus subgenomic RNA by the host nuclease XRN1. J. Virol. 2010;84:11395–11406. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01047-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friebe P, Harris E. Interplay of RNA elements in the dengue virus 5′ and 3′ ends required for viral RNA replication. J. Virol. 2010;84:6103–6118. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02042-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Polacek C, Foley JE, Harris E. Conformational changes in the solution structure of the dengue virus 5′ end in the presence and absence of the 3′ untranslated region. J. Virol. 2009;83:1161–1166. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01362-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olsthoorn RC, Bol JF. Sequence comparison and secondary structure analysis of the 3′ noncoding region of flavivirus genomes reveals multiple pseudoknots. RNA. 2001;7:1370–1377. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lo MK, Tilgner M, Bernard KA, Shi PY. Functional analysis of mosquito-borne flavivirus conserved sequence elements within 3′ untranslated region of West Nile virus by use of a reporting replicon that differentiates between viral translation and RNA replication. J. Virol. 2003;77:10004–10014. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.18.10004-10014.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alvarez DE, De Lella Ezcurra AL, Fucito S, Gamarnik AV. Role of RNA structures present at the 3′UTR of dengue virus on translation, RNA synthesis, and viral replication. Virology. 2005;339:200–212. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Romero TA, Tumban E, Jun J, Lott WB, Hanley KA. Secondary structure of dengue virus type 4 3′ untranslated region: impact of deletion and substitution mutations. J. Gen. Virol. 2006;87:3291–3296. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82182-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lodeiro MF, Filomatori CV, Gamarnik AV. Structural and functional studies of the promoter element for dengue virus RNA replication. J. Virol. 2009;83:993–1008. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01647-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.You S, Padmanabhan R. A novel in vitro replication system for Dengue virus. Initiation of RNA synthesis at the 3′-end of exogenous viral RNA templates requires 5′- and 3′-terminal complementary sequence motifs of the viral RNA. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:33714–33722. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.47.33714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mitra S, Shcherbakova IV, Altman RB, Brenowitz M, Laederach A. High-throughput single-nucleotide structural mapping by capillary automated footprinting analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:e63. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Badorrek CS, Weeks KM. Architecture of a gamma retroviral genomic RNA dimer. Biochemistry. 2006;45:12664–12672. doi: 10.1021/bi060521k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilkinson KA, Gorelick RJ, Vasa SM, Guex N, Rein A, Mathews DH, Giddings MC, Weeks KM. High-throughput SHAPE analysis reveals structures in HIV-1 genomic RNA strongly conserved across distinct biological states. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e96. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deigan KE, Li TW, Mathews DH, Weeks KM. Accurate SHAPE-directed RNA structure determination. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:97–102. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806929106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ciesiolka J, Michalowski D, Wrzesinski J, Krajewski J, Krzyzosiak WJ. Patterns of cleavages induced by lead ions in defined RNA secondary structure motifs. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;275:211–220. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen VB, Arendall WB, 3rd, Headd JJ, Keedy DA, Immormino RM, Kapral GJ, Murray LW, Richardson JS, Richardson DC. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2010;66:12–21. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chiu WW, Kinney RM, Dreher TW. Control of translation by the 5′- and 3′-terminal regions of the dengue virus genome. J. Virol. 2005;79:8303–8315. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.13.8303-8315.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clyde K, Harris E. RNA secondary structure in the coding region of dengue virus type 2 directs translation start codon selection and is required for viral replication. J. Virol. 2006;80:2170–2182. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.5.2170-2182.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ackermann M, Padmanabhan R. De novo synthesis of RNA by the dengue virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase exhibits temperature dependence at the initiation but not elongation phase. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:39926–39937. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104248200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nomaguchi M, Ackermann M, Yon C, You S, Padmanabhan R. De novo synthesis of negative-strand RNA by Dengue virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase in vitro: nucleotide, primer, and template parameters. J. Virol. 2003;77:8831–8842. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.16.8831-8842.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shapiro BA, Bengali D, Kasprzak W, Wu JC. RNA folding pathway functional intermediates: their prediction and analysis. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;312:27–44. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alvarez DE, Filomatori CV, Gamarnik AV. Functional analysis of dengue virus cyclization sequences located at the 5′ and 3′UTRs. Virology. 2008;375:223–235. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gutell RR, Cannone JJ, Konings D, Gautheret D. Predicting U-turns in ribosomal RNA with comparative sequence analysis. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;300:791–803. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Byun Y, Han K. PseudoViewer3: generating planar drawings of large-scale RNA structures with pseudoknots. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1435–1437. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shurtleff AC, Beasley DW, Chen JJ, Ni H, Suderman MT, Wang H, Xu R, Wang E, Weaver SC, Watts DM, et al. Genetic variation in the 3′ non-coding region of dengue viruses. Virology. 2001;281:75–87. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nissen P, Ippolito JA, Ban N, Moore PB, Steitz TA. RNA tertiary interactions in the large ribosomal subunit: the A-minor motif. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:4899–4903. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081082398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Isaksson J, Acharya S, Barman J, Cheruku P, Chattopadhyaya J. Single-stranded adenine-rich DNA and RNA retain structural characteristics of their respective double-stranded conformations and show directional differences in stacking pattern. Biochemistry. 2004;43:15996–16010. doi: 10.1021/bi048221v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cheong C, Varani G, Tinoco I., Jr Solution structure of an unusually stable RNA hairpin, 5′GGAC(UUCG)GUCC. Nature. 1990;346:680–682. doi: 10.1038/346680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Legiewicz M, Badorrek CS, Turner KB, Fabris D, Hamm TE, Rekosh D, Hammarskjold ML, Le Grice SF. Resistance to RevM10 inhibition reflects a conformational switch in the HIV-1 Rev response element. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:14365–14370. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804461105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abramovitz DL, Pyle AM. Remarkable morphological variability of a common RNA folding motif: the GNRA tetraloop-receptor interaction. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;266:493–506. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Villordo SM, Alvarez DE, Gamarnik AV. A balance between circular and linear forms of the dengue virus genome is crucial for viral replication. RNA. 2010;16:2325–2335. doi: 10.1261/rna.2120410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Popenda M, Szachniuk M, Antczak M, Purzycka KJ, Lukasiak P, Bartol N, Blazewicz J, Adamiak RW. Automated 3D structure composition for large RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:e112. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.De Nova-Ocampo M, Villegas-Sepulveda N, del Angel RM. Translation elongation factor-1alpha, La, and PTB interact with the 3′ untranslated region of dengue 4 virus RNA. Virology. 2002;295:337–347. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gomila RC, Martin GW, Gehrke L. NF90 binds the dengue virus RNA 3′ terminus and is a positive regulator of dengue virus replication. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16687. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ward AM, Bidet K, Yinglin A, Ler SG, Hogue K, Blackstock W, Gunaratne J, Garcia-Blanco MA. Quantitative mass spectrometry of DENV-2 RNA-interacting proteins reveals that the DEAD-box RNA helicase DDX6 binds the DB1 and DB2 3′ UTR structures. RNA Biol. 2011;8:1173–1186. doi: 10.4161/rna.8.6.17836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yocupicio-Monroy M, Padmanabhan R, Medina F, del Angel RM. Mosquito La protein binds to the 3′ untranslated region of the positive and negative polarity dengue virus RNAs and relocates to the cytoplasm of infected cells. Virology. 2007;357:29–40. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jaeger L, Michel F, Westhof E. Involvement of a GNRA tetraloop in long-range RNA tertiary interactions. J. Mol. Biol. 1994;236:1271–1276. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(94)90055-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Afonin KA, Lin YP, Calkins ER, Jaeger L. Attenuation of loop-receptor interactions with pseudoknot formation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:2168–2180. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brierley I, Pennell S, Gilbert RJ. Viral RNA pseudoknots: versatile motifs in gene expression and replication. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2007;5:598–610. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang C, Le SY, Ali N, Siddiqui A. An RNA pseudoknot is an essential structural element of the internal ribosome entry site located within the hepatitis C virus 5′ noncoding region. RNA. 1995;1:526–537. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wilson JE, Pestova TV, Hellen CU, Sarnow P. Initiation of protein synthesis from the A site of the ribosome. Cell. 2000;102:511–520. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00055-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brierley I, Pennell S. Structure and function of the stimulatory RNAs involved in programmed eukaryotic-1 ribosomal frameshifting. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 2001;66:233–248. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2001.66.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Imbert I, Guillemot JC, Bourhis JM, Bussetta C, Coutard B, Egloff MP, Ferron F, Gorbalenya AE, Canard B. A second, non-canonical RNA-dependent RNA polymerase in SARS coronavirus. EMBO J. 2006;25:4933–4942. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brierley I, Gilbert RJ, Pennell S. RNA pseudoknots and the regulation of protein synthesis. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2008;36:684–689. doi: 10.1042/BST0360684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zuo X, Wang J, Yu P, Eyler D, Xu H, Starich MR, Tiede DM, Simon AE, Kasprzak W, Schwieters CD, et al. Solution structure of the cap-independent translational enhancer and ribosome-binding element in the 3′ UTR of turnip crinkle virus. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:1385–1390. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908140107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McCormack JC, Yuan X, Yingling YG, Kasprzak W, Zamora RE, Shapiro BA, Simon AE. Structural domains within the 3′ untranslated region of Turnip crinkle virus. J. Virol. 2008;82:8706–8720. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00416-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tuplin A, Struthers M, Simmonds P, Evans DJ. A twist in the tail: SHAPE mapping of long-range interactions and structural rearrangements of RNA elements involved in HCV replication. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:6908–6921. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Theimer CA, Blois CA, Feigon J. Structure of the human telomerase RNA pseudoknot reveals conserved tertiary interactions essential for function. Mol. Cell. 2005;17:671–682. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Khromykh AA, Meka H, Guyatt KJ, Westaway EG. Essential role of cyclization sequences in flavivirus RNA replication. J. Virol. 2001;75:6719–6728. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.14.6719-6728.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Suzuki R, Fayzulin R, Frolov I, Mason PW. Identification of mutated cyclization sequences that permit efficient replication of West Nile virus genomes: use in safer propagation of a novel vaccine candidate. J. Virol. 2008;82:6942–6951. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00662-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Friebe P, Pena J, Pohl MO, Harris E. Composition of the sequence downstream of the dengue virus 5′ cyclization sequence (dCS) affects viral RNA replication. Virology. 2012;422:346–356. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2011.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gebhard LG, Kaufman SB, Gamarnik AV. Novel ATP-independent RNA annealing activity of the dengue virus NS3 helicase. PLoS One. 2012;7:e36244. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.