Abstract

Ceramide has been suggested to participate in the neuronal cell death that leads to Alzheimer’s disease (AD), but its role is not yet well-understood. We compared the levels of six ceramide subspecies, which differ in the length of their fatty acid moieties, in brains from patients who suffered from AD, other neuropathological disorders, or both. We found elevated levels of Cer16, Cer18, Cer20, and Cer24 in brains from patients with any of the tested neural defects. Moreover, ceramide levels were highest in patients with more than one neuropathologic abnormality. Interestingly, the range of values was higher among brains with neural defects than in controls, suggesting that the regulation of ceramide synthesis is normally under tight control, and that this tight control may be lost during neurodegeneration. These changes, however, did not alter the ratio between the tested ceramide species. To explore the mechanisms underlying this dysregulation, we evaluated the expression of four genes connected to ceramide metabolism: ASMase, NSMase 2, GALC, and UGCG. The patterns of gene expression were complex, but overall, ASMase, NSMase 2, and GALC were upregulated in specimens from patients with neuropathologic abnormalities in comparison with age-matched controls. Such findings suggest these genes as attractive candidates both for diagnostic purposes and for intervening in neurodegenerative processes.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, ceramide, neurodegeneration, sphingolipid biosynthesis, sphingolipid regulation

INTRODUCTION

Dementia and its most common cause, Alzheimer’s disease (AD), are age-related disorders, with 35–40% of the population older than 85 years having been diagnosed with one or more neurodegenerative diseases [1]. It is believed that the major immediate cause of the majority of neurological disorders is the atypical death of neuronal cells. Numerous extrinsic and intrinsic pathways can lead to untimely apoptosis, and among these, the ceramide pathway has recently attracted increasing attention as an important and possibly critical factor in several neuropathological processes [2, 3].

Ceramide, a core constituent of all complex sphingolipids, plays a vital role in numerous fundamental cellular processes, including growth, differentiation, cell cycle arrest, senescence, survival, and apoptosis [4]. Ceramide consists of a sphingosine backbone attached to fatty acid by an amide bond. In mammals, ceramide is represented by a group of several subspecies that differ in the length of their fatty acid moiety, which can vary between 2 and 24 carbons in length. Though the biological significance of these varied fatty acid lengths remains obscure, a characteristic tissue-specific expression pattern of ceramide synthases, a family of enzymes where each member synthesizes a distinct ceramide species, has been observed [5].

Recent advances in the development of new analytical methods for rapid and sensitive qualitative analysis of ceramide species in biological samples using electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry [6–8] have provided a set of effective and essential tools for the analysis of ceramide content in brain tissues. Such analyses are necessary in order to delineate the mechanism (s) by which the various ceramides contribute to or protect from neurodegenerative processes. Furthermore, the analyses of genes that code for proteins involved in ceramide metabolism in neural cells, both during normal function and in the course of neurological disease, have the potential to help us to understand the molecular mechanisms by which ceramide levels are controlled. Such insights may, in turn, enable us to design novel and effective therapeutic approaches.

In this report, we determined the levels of six ceramide species in 40 specimens of human brain, obtained postmortem from patients diagnosed with different neuropathologic abnormalities. In these specimens, we also estimated the expression levels of several genes known to be involved in the ceramide metabolic pathway in neuronal cells. We observed an increase in ceramide in samples corresponding to specific diagnoses, with the greatest increase seen in specimens with multiple neuropathologic abnormalities. However, we did not find statistically significant alterations in the ratios between the different ceramide species, either in control brains or in brains from patients with lesions. We also found a complex expression pattern for four genes that regulate ceramide levels in neural cells. Overall, ASMase, NSMase 2, and GALC were upregulated in specimens from patients with neuropathologic abnormalities in comparison with age-matched controls, while UGCG was down-regulated. These findings suggest that one or more of these genes may serve as potential targets for the diagnosis, prevention and/or interception of neurodegenerative processes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals

All organic solvents were of HPLC grade and were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA) or Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). All ceramide species were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, Alabama). The HPLC Pursuit 3 PFP 50 × 2.0mm column was obtained from Varian (Lake Forest, CA).

Brain tissues

Human brain samples were obtained from the Neuropathology Core/Brain Bank of the UCLA Mary Easton Alzheimer Disease Center. All samples were handled and dissected while frozen, and ceramide measurements were performed blind with regards to diagnosis. All brain sample specimens were from frontal cortices. Patients were divided into four groups based on their diagnosed neurological status (Table 1). 19 patients were diagnosed with pure AD at various stages, 6 patients had mixed diagnoses (AD accompanied by other neuropathologic lesions), 9 patients had non-AD dementia (such as frontotemporal lobar degeneration, tauopathy, or diffuse Lewy body disease), and a control group of 6 patients had no diagnosed neuropathologic abnormality. Detailed data regarding the patients, the postmortem interval, and their diagnosed pathologies is provided in Table 1. All tissues were kept frozen without fixative at−80° Cuntil homogenization.

Table 1.

Patient information

| Diagnosis | n | Males | Females | AVG Age | AVG PMI (h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pure AD B&B stage less than B&B VI | 7 | 4 | 3 | 85.4 | 17.6 |

| Pure AD B&B stage VI | 12 | 3 | 9 | 83.9 | 14.7 |

| Mixed AD (+other pathology) | 6 | 3 | 3 | 82.8 | 24.3 |

| Non-AD dementia | 9 | 4 | 5 | 73.0 | 12.4 |

| Control | 6 | 5 | 1 | 66.2 | 22.7 |

| Total | 40 | 19 | 21 | 78.3 | 18.3 |

Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer’s disease; AVG, average; B&B stages, Braak stages from I to VI; PMI, postmortem Interval (in hours) between death and brain removal.

Preparation of brain sample homogenates

Dissected frozen brain tissue was weighed and placed into a glass scintillation vial (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) with sterile PBS (1 ml of PBS per 0.1 g of brain tissue). Each sample was homogenized using a handheld electric homogenizer TissueMiser (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) until completion, then separated into three aliquots for lipid extraction, RNA purification, and protein concentration measurement. 50µl of homogenate was used to measure protein concentration with the DC Protein Assay Kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), 0.5 ml of homogenate was used for RNA isolation, as described below, and 1ml was used for lipid extraction.

Lipid extraction

Three ml of methanol was added to 1ml of homogenate, followed by the addition of 100 µl of 50 ng/ml Cer17 (used as an internal standard), and the mixture was vortexed and sonicated for 30 min in an ultrasonic bath. Lipid extraction with 2ml of chloroform was performed twice, and the lower chloroform fractions after centrifugation were combined in a fresh glass tube and evaporated under nitrogen. Lipids were dissolved in 1ml of acetonitrile, sonicated for 15 min in an ultrasonic bath, and subjected to electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry (ESI/MS/MS) analysis for evaluation of ceramide concentration.

Ceramide measurements

ESI/MS/MS analyses were performed using methods similar to those described in our previous publications [6, 8]. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was performed using an Agilent Technologies Model 1200 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Lipids were separated on a Pursuit 3 Diphenyl reversed-phase column, 50 × 2.0mm i.d., 3µm (Varian, Lake Forest, CA) using the mobile phases – A: 0.1% formic acid, and 25mM ammonium acetate in water, and B: 100% acetonitrile. The ion source employed was the ESI of an Agilent triple quadrupole 6410 mass spectrometer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) and ionization was performed in the positive ion mode. The multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode was employed for monitoring precursor ions, m/z 324.3 for Cer2, 380.4 for Cer6, 538.4 for Cer16, 566.5 for Cer18, 594.6 for Cer20, and 650.7 for Cer24 ceramide, and product ion m/z 264.2 for all species. The MRM transition for Cer17, which served as the internal standard (IS), was m/z 552.5 (precursor ion) – m/z 264.2 (product ion). The instrumental MassHunter software with qualitative analysis and quantitative features was used to process the data.

RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis, and quantitative PCR

Brain homogenates (0.5 ml) were centrifuged for 5 min, and pellets were subjected to RNA isolation using 0.5 ml of TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to manufacturer’s protocol. The final RNA precipitates were dissolved in 100 µl of water and additionally extracted with acid phenol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) to further purify from DNA contamination, followed by ethanol precipitation. RNA pellets were dissolved in 20–100 µl of water and concentration was measured using a NanoDrop-2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE). To synthesize cDNA, 1 µg of total RNA and 0.5µg of oligo (dT) primer were used with ImProm-II™ Reverse Transcription System according to the company’s protocol (Promega, Madison, WI). The cDNA samples were further used for quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) analysis to estimate the transcription levels of several genes in total RNA samples. To perform real-time qPCR, a QuantiTect SYBR PCR kit (Invitrogen) in a CFX96 PCR System (Bio-Rad) was employed according to the manufacturer’s protocols. Each brain sample was run in triplicate for each gene analysis. To detect gene-specific signals, the following sets of primers were used: for PGK1, which was used for normalization, CTGTGGGGGTATTTGAATGG and CTICCAGGAGCTCCAAACTG; for UGCG, TTCAATCCA GAATGATCAGGT and TATAGTTGGGTCCCATAATGC; for ASMase (SMPD1), GTGAGAACTTCTGGCTCTTGA and ATGTGGCCAATTATATGCACT; for NSMase 2 (SMPD3), ATCGGTACTCTGCTGGACAC and GACAGCTGGGTGATAAAACTG; and for GALC, TTCTCAACCAGAGACCCATTA and GCTGTAACTTCAACACGTCCT.

Statistical analysis

Each experiment was performed at least three times, and each assay point was measured in triplicate. Values are expressed as means ± standard deviation. Results shown are from representative experiments. Student’s one- or two-tailed t tests, as appropriate, were used for statistical analysis, with values of < 0.05 considered to be statistically significant. Calculations and creation of box plot graphs were done using the Vertex42 Excel template (http://www.vertex42.com).

RESULTS

Detection of Cer2, Cer6, Cer16, Cer18, Cer20, and Cer24 in human brain samples

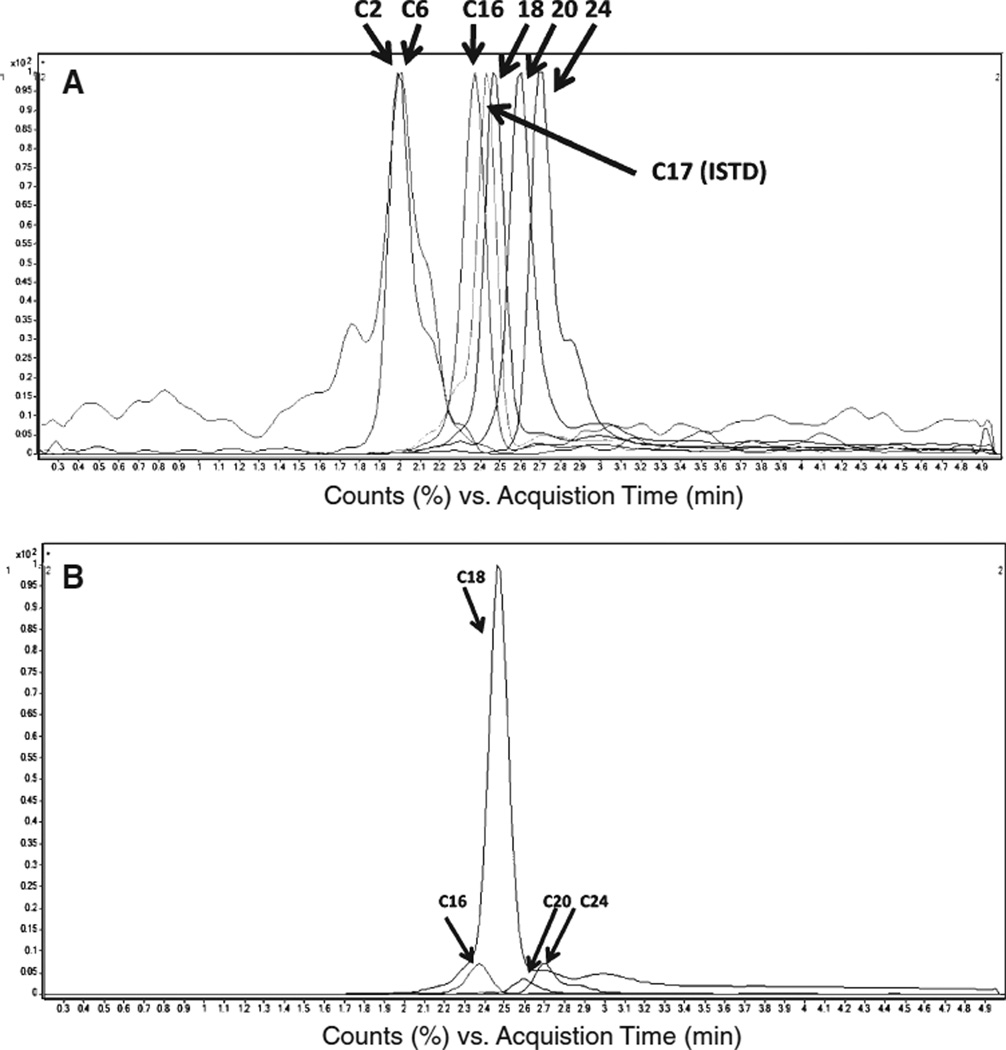

We used ESI/MS/MS to determine and evaluate the concentration of several species of ceramide in human brain samples [6, 8]. This method allowed us to simultaneously measure the concentrations of six ceramides that differ only in the length of their fatty acid moieties: ceramide C2 : 0 (Cer2); ceramide C6 : 0 (Cer6); ceramide C16 : 0 (Cer16); ceramide C18 : 0 (Cer18); ceramide C20 : 0 (Cer20); and ceramide C24 : 0 (Cer24). At the same time, we measured ceramide C17 : 0 (Cer17), used as an internal standard. Figure 1A shows a typical chromatogram of a sample of brain lipid extract. While the total time of each run was 5 min, all six ceramides were detected within the first 2.7 min, starting with the shortest, Cer2, and ending with the longest, Cer24. All six detected ceramides were represented in very unequal quantities, as shown on the unscaled chromatogram of brain lipid extract (Fig. 1B). Quantification of the individual ceramides using standard curves for each species revealed that the median concentration of the most abundant form of ceramide, Cer18, in all analyzed brain samples was 40µg/g of brain tissue, ranging from 28.7 to 84 µg/g (51–148 nmole/g) among all samples tested. One of the less abundant ceramides, Cer2, was present at a median concentration of only 43.7 ng/g (0.13 nmole/g) in analyzed samples, while Cer6, the least abundant ceramide species we measured, was found at barely detectable levels in only a few samples.

Fig. 1.

MRMchromatograms of ceramide species found in lipids isolated from brain specimens. A) Unscaled MRM-chromatogram of ceramide species. B) Scaled-mode of the MRM chromatogram for a typical lipid brain sample. Peaks for Cer2 and Cer6 are too small to be seen on this chromatogram.

The ratio between ceramide species does not differ significantly between normal and diseased brains

We compared the ratio between the individual ceramide species in brain tissues isolated from four groups of patients: Age-matched controls (CNTRL), patients diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease (AD), patients diagnosed with other neuropathologies (NP), and patients diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease plus another neuropathology (AD+NP). Table 2 shows the relative compositions, expressed as percentages, of the six detected ceramide species in brain samples from these four groups of patients, where 100% represents the total of all six ceramides. As shown, Cer18 accounts for more than 90 percent of all ceramides analyzed, and Cer16 is the second most abundant ceramide in brain tissue. However, Cer16 constitutes only between 3.7 and 6.1 percent of total ceramide. The remainder of the ceramide species is present at even smaller proportions of the total pool. Cer24 represents less than 2% of total detected ceramide, and Cer20, Cer2, and Cer6 account for less than one percent each.

Table 2.

Ceramide distribution

| Ceramide 2 | Ceramide 6 | Ceramide 16 | Ceramide 18 | Ceramide 20 | Ceramide 24 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AD (19) | 0.31 ± 0.82 | 0.006 ± 0.026 | 4.57 ± 1.61 | 92.98 ± 2.47 | 0.71 ± 0.22 | 1.42 ± 0.72 |

| AD+NP (6) | 0.24 ± 0.16 | 0.014 ± 0.033 | 6.16 ± 1.12 | 90.99 ± 1.78 | 0.76 ± 0.11 | 1.84 ± 0.59 |

| NP (9) | 0.14 ± 0.11 | 0.006 ± 0.019 | 4.66 ± 0.98 | 93.20 ± 1.97 | 0.71 ± 0.29 | 1.28 ± 0.74 |

| CNTRL (6) | 0.10 ± 0.05 | 0.000 ± 0 | 3.71 ± 1.05 | 93.80 ± 1.43 | 0.83 ± 0.08 | 1.56 ± 0.72 |

Data expressed in percentages of the mean ± SD.

The data displayed in Table 2 shows that the relative ratio between the six ceramide species is approximately the same in all 4 groups studied, and that the differences between them are statistically insignificant.

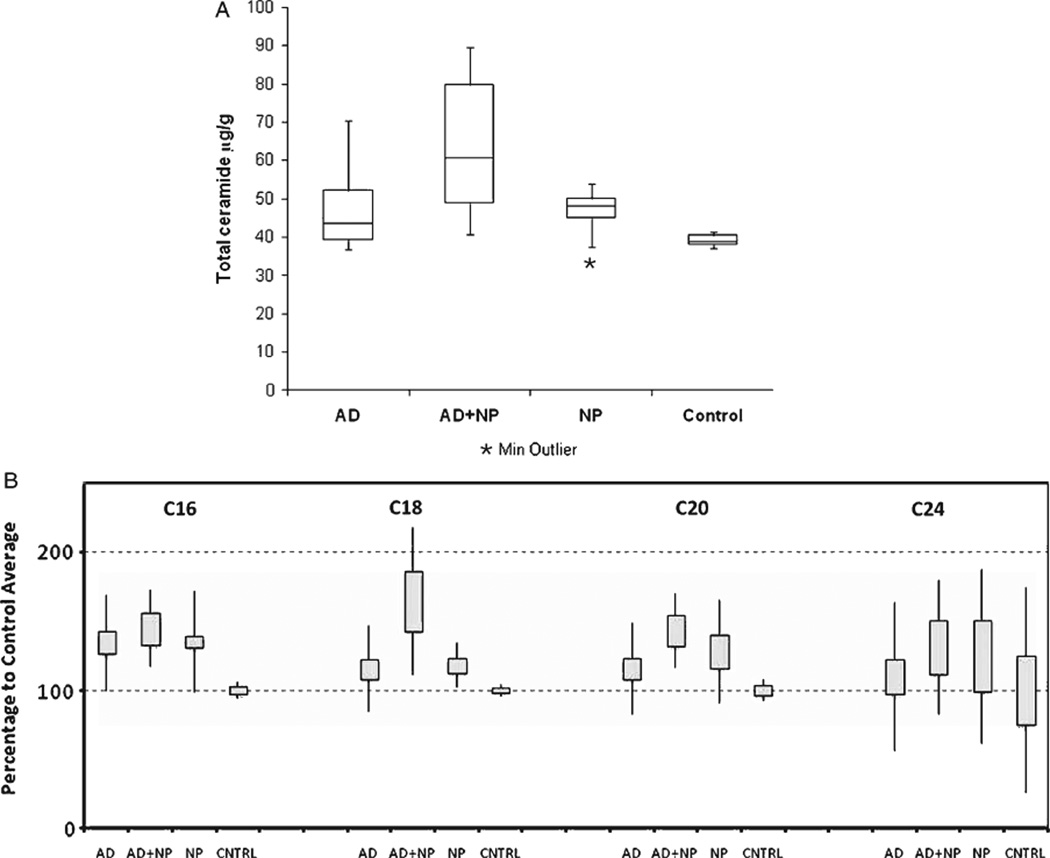

Ceramide levels are elevated in tissues undergoing neurodegeneration

Though no significant changes were detected in the relative composition of the different ceramides in the brains of patients from our four study groups, we did find significant differences in the absolute levels of several ceramide species when we compared the four groups. Figure 2A shows ceramide levels in brain tissue samples from brains affected by AD, AD featuring additional neurodegenerative features (AD+NP), and neuropathological abnormalities other than AD (NP), as compared to tissue samples from age-matched brains with no degeneration (CNTRL). The data shows a significant increase in levels of total ceramide in all groups with neuropathologic abnormalities as compared to the Control group: p = 0.04 for the AD group; p = 0.008 for the NP group; and p = 0.006 for the AD+NP group. Significant changes were also observed for the individual ceramide species. Figure 2B shows the relative levels of four ceramides (Cer16, Cer18, Cer20, and Cer24) in these groups. Each of these four ceramide species displayed the same trend; namely, that the average ceramide concentrations were elevated in all groups with neurodegenerative features as compared to control samples. In addition, the group with two different types of neuropathologic abnormalities (AD+NP) had the highest level of ceramide, and this trend was the most evident for Cer18, the major ceramide species in these brain specimens (Fig. 2). This trend was least evident for Cer24, though it should be noted that the wide range in values for Cer24 (also note the low absolute levels) led to large standard deviations that would tend to mask such differences. It may be that our measurement conditions were not optimal for this species. The values for Cer16, Cer18, and Cer20 were quite tightly clustered for the control patients, suggesting that that regulation of ceramide levels is normally under tight control. However, the samples from brain samples obtained from patients with one or more neuropathological abnormalities displayed a much higher divergence in their level of ceramides, which may reflect a deregulation of ceramide biosynthesis during AD progression, as has previously been observed [9]. Our data suggests that this deregulation may also occur during other degenerative processes.

Fig. 2.

Ceramide levels in human brain specimens. A) Box plots of ceramide determined in four groups of patients, showing significant increases in ceramide levels in brains with lesions. All 40 brain specimens were divided into four groups. 19 brain samples were from patients diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease (AD group), and AD+NP represents a group of 6 samples from patients with AD accompanied by other neuropathological features. The NP group of 9 samples was obtained from patients with degenerative diseases other than AD, and the control (CNTRL) group of 6 age-adjusted brain samples did not have any diagnosed neuropathologic abnormalities. Plots display the median (horizontal line in the box), as well as the first (Q1) and third (Q3) quartiles (boxes). Bars outside the boxes represent extreme values. One outlier found in the NP group, as identified by the program, is marked as a star. B) Concentrations of four individual ceramide species in the same four groups of patients. Boxes represent Mean ± S.E.M. values, and the lines cover regions calculated as Mean ± SD.

Four genes involved in ceramide biosynthesis display altered expression

We used quantitative RT-PCR analysis to evaluate the expression levels of 4 genes that may be involved in our observed upregulation of ceramide levels. We selected UGCG, which codes for a key enzyme in the conversion of ceramide into glycosphingolipids; GALC, which produces ceramide from galactosylceramide; and two sphingomyelinases, which form ceramide from sphingomyelin: ubiquitous ASMase and brain-specific NSMase 2. We did not select genes coding for proteins involved in de novo ceramide synthesis, as this pathway represents a complex group of genes with a large number of regulation points.

In total, 15 brain samples were selected for gene expression analysis. These samples were chosen from 3 of the 4 groups previously noted: 3 samples of age-matched controls (CNTRL), 8 samples from patients diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease (AD), and 4 samples from patients diagnosed with neuropathologies other than AD (NP). Within each group, we selected brain samples with the highest and lowest ceramide levels. For the NP samples, we also selected two specimens with an average ceramide level, and for AD samples, we analyzed 6 additional samples with low and intermediate ceramide concentrations. Figure 3 shows the expression levels of our 4 selected genes from these samples, and compares these values to the individual levels of ceramide in the same samples. The results are shown as percentages of the highest measured concentration among the samples, and arranged by total ceramide levels within the groups, lowest to highest, where this total includes all six ceramide species quantified. Analysis of expression levels of the two sphingomyelinases, ASMase and brain specific NSMase 2, shows upregulation of transcription for both these enzymes in AD and NP brain samples (Fig. 3, two upper panels). All four NP brain specimens have much higher levels of ASMase compared to the controls, while NSMase 2 has significantly higher expression in only two samples out of the four analyzed. In AD brains, the majority of samples also have higher expression of both genes; in only 1 out of 8 samples (sample 4) are the ASMase and NSMase 2 expression levels close to the control level.

Fig. 3.

Expression levels of four genes connected to the ceramide pathway, as measured by qRT-PCR in 15 brain specimens and divided into 3 groups: Alzheimer’s disease (AD, black bars), neuropathologies other than AD (NP, grey bars), and three control (CNTRL) brain samples shown as white bars. Expression of genes was normalized against expression of the PGK1 gene. Expression data for the ASMase, NSMase 2, UGCG, and GALC genes are displayed according to ceramide levels as determined in the particular brain sample (lowest panel). All values are displayed as percentages of the highest value in the group. Bars show SD values for three replicates for real time PCR expression levels values and three measurements for ceramide.

The expression pattern for GALC, which like the sphingomyelinases produces ceramide from other sphingolipids, resembles the NSMase 2 pattern, particularly in the case of the NP brain samples (Figure 3, left middle panel). However, only two of the AD samples show a higher expression of GALC. Expression of UGCG, decreased levels of which should lead to increased ceramide levels [10], showed a complex pattern in the tested samples (Figure 3, middle left panel). When compared to control brain samples, UGCG expression was indeed decreased in almost half of the samples with neuropathological abnormalities (7 out of 12). However, this trend was not universal, and four of the AD samples showed higher levels of UGCG expression.

DISCUSSION

Several lines of evidence have begun to suggest the possible involvement of ceramides in the development of AD [2, 3]. To explore this possibility further, it was necessary to employ sensitive and quantitative analytical approaches. The liquid chromatography ESI/MS/MS method serves this need, as it enables the simultaneous measurement in biological samples of several different ceramide species present at concentrations ranging from nM to µM. Using a variant of this technique optimized for ceramide detection [8], we were able to identify and quantify six ceramide species in human brain samples with and without diagnoses of neuropathological abnormalities. Evaluation of ceramide levels within these samples revealed a wide range of concentrations, from barely detectable signals for Cer2 and Cer6, to more than 140 nmole/g for Cer18, the most abundant species in this tissue.

To assess possible changes in ceramide content during neurodegeneration, we analyzed ceramide levels in 40 brain specimens obtained from patients that were divided into four groups (Table 1). The largest group (AD) had 19 samples obtained from patients diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. The NP group of 9 samples was obtained from patients with neuropathologic entities other then AD, such as tauopathy, Parkinson’s disease, and diffuse Lewy body disease, and the AD+NP group included 6 samples from patients that had AD along with an additional neuropathologic abnormality (usually one or more infarcts). Ceramide levels in these groups were compared to the Control group of 6 age-adjusted brain samples without diagnosed neurodegenerative diseases. Comparing the relative levels of six ceramide species in brain tissue between any of these four groups of patients analyzed in this study did not reveal any statistically significant differences (Table 2). Interestingly, our observed ratio of ceramide species matches more closely to the ratio found in rat brains than to ratios found in other rat tissues [11]. This observation suggests that the ceramide species composition may be more specific for tissue than for species. Also, this observed absence of significant changes in the ratio indicates that although brain tissue undergoes major physiological and morphological changes during neurodegeneration, significant tissue-specific features are retained.

Comparative analysis of the levels of individual ceramide species in brains with AD and other neuropathologic entities revealed a statistically significant increase in the levels of Cer16, Cer18, and Cer20, along with an increase in Cer24 that does not reach statistical significance (Fig. 2B). Sphingolipid imbalance during neurodegeneration, including elevated levels of ceramide, has been previously observed (reviewed in [2]). Our data on levels of ceramide species that can be quantified with a high level of accuracy, such as Cer16, Cer18, and Cer20, show that each of them is more abundant in brains with neuropathologic abnormalities than in controls, with their levels the highest in brains with multiple neurodegenerative pathologies. We also found that the range in ceramide levels between individual brain samples is much higher in brains with neural defects than in unaffected controls. This indicates, first, that the regulation of ceramide concentrations is normally under tight control, and second, that regulation of ceramide biosynthesis becomes dysfunctional during neurodegeneration.

Ceramide formation in neural cells is regulated by two major pathways, de novo biosynthesis from serine and fatty acids, and a salvage pathway that utilizes acylation of sphingosine (reviewed in [12]). In addition to these two synthetic pathways, ceramide can be metabolized and converted into other sphingolipid molecules (Fig. 4). The physiological importance of these metabolism and conversion events, as well as their impact on the level of ceramide in neural cells, has become increasingly evident in recent years due to several studies of the role of sphingolipid metabolism in neuropathogenesis [13]. Since the first report in 1992 of a decrease in the level of total phospholipids in AD brains [14], this observed disturbance in the metabolism of sphingolipids, including ceramide, during AD has led to several attempts to identify the genes and proteins responsible for this dysregulation. The facts that a large number of enzymes are involved in these pathways, and that the activity of these enzymes can in turn be regulated by additional genes and proteins, have made this task a challenging one. Global expression analysis of RNA isolated from brains at different stages of AD progression identified 28 genes involved in ceramide metabolism with altered expression, suggesting that alterations in their expression may be linked to AD progression [15]. Among these genes, three encode ceramide synthases, with CerS1 and CerS2 found to be upregulated while CerS6 was significantly down-regulated. This data indicates that the observed increase of at least some ceramide species in AD brains may be the result of sphingosine acylation. However, the unchanged ratio between ceramide species that we observed in the presence and absence of neuropathological processes (Table 2) indicates that synthesis of individual ceramide species is not regulated only by changes in expression of individual CerS genes. Indeed, biochemical characterization of the CerS enzymes 2, 5, and 6 in HeLa cells revealed that these enzymes may exist as complexes in the cell, which would provide an additional level of regulation for the balance between the various ceramide species [16].

Fig. 4.

Scheme showing the major pathways involved in the regulation of ceramide levels. De novo synthesis and the salvage pathway are major sources of ceramide formation. Ceramide is also a source for the synthesis of other sphingolipids, such as sphingomyelin, glucosylceramides, and galactosylceramides, and ceramide also may be produced from these lipids. Four enzymes, whose expression patterns were analyzed in this manuscript, are noted.

Two additional enzymes involved in the regulation of ceramide levels in cells were found to have altered expression profiles during AD progression. Expression of galactosylceramidase (GALC), a deficiency of which can cause Krabbe’s disease (a leukodystrophy), was found to be elevated as AD progressed [15]. Increases in GALC can lead to an increase in ceramide levels, since this enzyme catalyzes conversion of galactosylceramide into ceramide. Expression of UDP-glucose ceramide glucosyltransferase (UGCG) was also found to be down-regulated in AD patients in this microarray analysis. UGCG regulates synthesis of glucosylceramide from ceramide, so decreased UGCG activity has the potential to increase ceramide levels. An additional study also registered lower UGCG activity in the AD frontal cortex as compared to age-matched controls [17]. These studies suggest both GALC and UGCG as possible candidates responsible for the increased ceramide levels noted in brains diagnosed with AD and other neurodegenerative diseases.

To test the possible involvement of the GALC and UGCG genes in regulating ceramide levels in our brain specimens, we determined their expression levels by quantitative RT-PCR. We also analyzed the expression of two additional enzymes that might upregulate ceramide levels in brains undergoing neurodegeneration: acid and neutral sphingomyelinases (SMases). Sphingomyelinases are members of the phospholipase family that catalyze the hydrolysis of sphingomyelin to ceramide and phosphocholine. Two types of sphingomyelinases are encoded by 4 different genes in humans, and can be distinguished by their optimal pH, acid or neutral. Acid SMase (ASMase), which is located in lysosomes of the neuron cell body, may play a role in neural pathophysiology, as its activity has been linked to depression [18, 19]. Neutral SMases (NSMases) are encoded by three genes, not closely related, that differ in their biochemical and physiological characteristics. The NSMase 1 and NSMase 3 genes are expressed ubiquitously in many tissues, both at the transcriptional and translational levels, while NSMase 2 is expressed predominantly in brain [20]. Involvement of NSMase2 and ASMase activities in AD progression by up-regulation of ceramide has been recently proposed [9, 21]. Therefore, we determined their expression levels along with those of UGCG and GALC.

The expression levels of these four genes were compared to the corresponding ceramide levels in the same specimens, as shown in Fig. 3. As expected, the results showed complicated expression patterns in the individual brain samples. This may mean that there are a variety of mechanisms that can lead to altered ceramide metabolism in the brains of patients with neurodegenerative diseases, such that each patient has a somewhat different molecular history. These results also indicate that the four genes we studied (ASMase, NSMase, GALC, andUGCG)are likely to be involved in this dysregulation. Interestingly, we found major changes in the expression of these genes in some neuropathological brain samples that had total ceramide levels near that of the controls, suggesting that factors related to ceramide metabolism, in addition to the total ceramide level, may also contribute to the development of neurodegeneration.

Elevated expression of sphingomyelinases, and in particular, ASMase, in the majority of samples with neuropathologies indicates their likely involvement in the dysregulation of ceramide pathways. Expression patterns of GALC and NSMase 2 are similar in the NP group, but less so in the AD samples (Fig. 3). Increased expression of these three enzymes is anticipated to lead to an increase in the ceramide concentration due to the hydrolysis of galactosylceramide and sphingomyelin, thus yielding ceramide (Fig. 4). However, we were not able to show that when comparing individual samples within either the NP or the AD group, higher expression of these three genes correlated with higher ceramide levels, and in fact, the opposite trend was noted, most evident for NSMase2. This may mean that the major sources of increased ceramide in these cells may not be from pathways that produce additional ceramide from sphingomyelins and galactosylceramides. UGCG, in contrast, facilitates a decrease in ceramide concentration by transforming it into glucosylceramide (Fig. 4). However, we were again unable to correlate increased levels within the AD group to decreased ceramide levels, as there was a high variability in UGCG expression among this group of samples. Overall, our results indicate both that dysregulation of genes involved in ceramide metabolism is a frequent occurrence during the development of neurodegenerative disease, and that the specific patterns of change are likely to be complex and to vary significantly from one patient to another.

One possible explanation for the complicated relationships observed between ceramide levels in brain tissues, and the expression levels of genes involved in ceramide metabolism as measured in the same samples, may be connected to the fact that some ceramide production could occur outside of brain tissues. Ceramide is known to be able to easily cross the blood-brain barrier [22], and therefore, the expression of genes involved in ceramide metabolic pathways could reflect not only in situ production but also the response to external ceramide. Recent studies examining the role of the liver-brain axis in the context of neurodegeneration caused by alcohol abuse provide one such example [23]. Simultaneous measurements of ceramide in several tissues, such as brain, plasma, cerebrospinal fluid, and internal organs could be used to address this question. As a related issue, it may be that some of the observed changes are compensatory in nature.

Our ability to simultaneously analyze cellular ceramide levels and the expression of genes involved in ceramide metabolism has now made it possible, within the same sample, to describe both an apparent disturbance in ceramide homeostasis, and changes in the expression of genes involved in the regulation of its metabolism. The highest ceramide levels were found in samples from brains affected by more than one neural disease, strongly suggesting that changes in this set of pathways are connected to the development of neuropathologies. Consequently, the enzymes and metabolites within these pathways have the potential to be developed into novel and effective targets for intervening in these debilitating and costly diseases.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

H.V.V. and S.T. were supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (P50 AG16570).

Authors’ disclosures available online (http://www.j-alz.com/disclosures/view.php?id=1102).

REFERENCES

- 1.Scott KR, Barrett AM. Dementia syndromes: Evaluation and treatment. Expert Rev Neurother. 2007;7:407–422. doi: 10.1586/14737175.7.4.407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jana A, Hogan EL, Pahan K. Ceramide and neurodegeneration: Susceptibility of neurons and oligodendrocytes to cell damage and death. J Neurol Sci. 2009;278:5–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2008.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cutler RG, Kelly J, Storie K, Pedersen WA, Tammara A, Hatanpaa K, Troncoso JC, Mattson MP. Involvement of oxidative stress-induced abnormalities in ceramide and cholesterol metabolism in brain aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:2070–2075. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305799101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pettus BJ, Chalfant CE, Hannun YA. Ceramide in apoptosis: An overview and current perspectives. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1585:114–125. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(02)00331-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Imgrund S, Hartmann D, Farwanah H, Eckhardt M, Sandhoff R, Degen J, Gieselmann V, Sandhoff K, Willecke K. Adult ceramide synthase 2 (CERS2)-deficient mice exhibit myelin sheath defects, cerebellar degeneration, and hepatocarcinomas. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:33549–33560. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.031971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haynes TA, Duerksen-Hughes PJ, Filippova M, Filippov V, Zhang K. C18 ceramide analysis in mammalian cells employing reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Biochem. 2008;378:80–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2008.03.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kasumov T, Huang H, Chung YM, Zhang R, McCullough AJ, Kirwan JP. Quantification of ceramide species in biological samples by liquid chromatography electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Biochem. 2010;401:154–161. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2010.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang K, Haynes T-AS, Filippova M, Filippov V, Duerksen-Hughes PJ. Quantification of ceramide levels in mammalian cells by high performance liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry with multiple-reaction-monitoring mode (HPLC-MS/MS-MRM) Analytical Methods. 2011;3:1193–1197. [Google Scholar]

- 9.He X, Huang Y, Li B, Gong CX, Schuchman EH. Deregulation of sphingolipid metabolism in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2010;31:398–408. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jennemann R, Sandhoff R, Wang S, Kiss E, Gretz N, Zuliani C, Martin-Villalba A, Jager R, Schorle H, Kenzelmann M, Bonrouhi M, Wiegandt H, Grone HJ. Cell-specific deletion of glucosylceramide synthase in brain leads to severe neural defects after birth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:12459–12464. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500893102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laviad EL, Albee L, Pankova-Kholmyansky I, Epstein S, Park H, Merrill AH, Jr, Futerman AH. Characterization of ceramide synthase 2: Tissue distribution, substrate specificity, and inhibition by sphingosine 1-phosphate. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:5677–5684. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707386200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Colombaioni L, Garcia-Gil M. Sphingolipid metabolites in neural signalling and function. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2004;46:328–355. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Echten-Deckert G, Herget T. Sphingolipid metabolism in neural cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1758:1978–1994. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nitsch RM, Blusztajn JK, Pittas AG, Slack BE, Growdon JH, Wurtman RJ. Evidence for a membrane defect in Alzheimer disease brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:1671–1675. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.5.1671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katsel P, Li C, Haroutunian V. Gene expression alterations in the sphingolipid metabolism pathways during progression of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: A shift toward ceramide accumulation at the earliest recognizable stages of Alzheimer’s disease? Neurochem Res. 2007;32:845–856. doi: 10.1007/s11064-007-9297-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mesicek J, Lee H, Feldman T, Jiang X, Skobeleva A, Berdyshev EV, Haimovitz-Friedman A, Fuks Z, Kolesnick R. Ceramide synthases 2, 5, and 6 confer distinct roles in radiation-induced apoptosis in HeLa cells. Cell Signal. 2010;22:1300–1307. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marks N, Berg MJ, Saito M, Saito M. Glucosylceramide synthase decrease in frontal cortex of Alzheimer brain correlates with abnormal increase in endogenous ceramides: Consequences to morphology and viability on enzyme suppression in cultured primary neurons. Brain Res. 2008;1191:136–147. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.10.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kornhuber J, Medlin A, Bleich S, Jendrossek V, Henkel AW, Wiltfang J, Gulbins E. High activity of acid sphingomyelinase in major depression. J Neural Transm. 2005;112:1583–1590. doi: 10.1007/s00702-005-0374-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jenkins RW, Canals D, Hannun YA. Roles and regulation of secretory and lysosomal acid sphingomyelinase. Cell Signal. 2009;21:836–846. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hofmann K, Tomiuk S, Wolff G, Stoffel W. Cloning and characterization of the mammalian brain-specific, Mg2+-dependent neutral sphingomyelinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:5895–5900. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.11.5895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu BX, Clarke CJ, Hannun YA. Mammalian neutral sphingomyelinases: Regulation and roles in cell signaling responses. Neuromolecular Med. 2010;12:320–330. doi: 10.1007/s12017-010-8120-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zimmermann C, Ginis I, Furuya K, Klimanis D, Ruetzler C, Spatz M, Hallenbeck JM. Lipopolysaccharide-induced ischemic tolerance is associated with increased levels of ceramide in brain and in plasma. Brain Res. 2001;895:59–65. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02028-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de la Monte SM, Longato L, Tong M, DeNucci S, Wands JR. The liver-brain axis of alcohol-mediated neurodegeneration: Role of toxic lipids. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2009;6:2055–2075. doi: 10.3390/ijerph6072055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]