Key Points

D1472H sequence variation is associated with a decreased VWF:RCo/VWF:Ag ratio in type 1 VWD subjects.

D1472H sequence variation is not associated with an increase in bleeding as measured by bleeding score in type 1 VWD subjects.

Abstract

The diagnosis of von Willebrand disease (VWD) is complicated by issues with current laboratory testing, particularly the ristocetin cofactor activity assay (VWF:RCo). We have recently reported a sequence variation in the von Willebrand factor (VWF) A1 domain, p.D1472H (D1472H), associated with a decrease in the VWF:RCo/VWF antigen (VWF:Ag) ratio but not associated with bleeding in healthy control subjects. This report expands the previous study to include subjects with symptoms leading to the diagnosis of type 1 VWD. Type 1 VWD subjects with D1472H had a significant decrease in the VWF:RCo/VWF:Ag ratio compared with those without D1472H, similar to the findings in the healthy control population. No increase in bleeding score was observed, however, for VWD subjects with D1472H compared with those without D1472H. These results suggest that the presence of the D1472H sequence variation is not associated with a significant increase in bleeding symptoms, even in type 1 VWD subjects.

Introduction

Von Willebrand disease (VWD) is the most common inherited bleeding disorder, but diagnosis is fraught with difficulty. Laboratory testing for VWD utilizes both the von Willebrand factor (VWF) antigen (VWF:Ag) and the VWF ristocetin cofactor activity assay (VWF:RCo). Although VWF:Ag testing is highly reproducible, it does not measure VWF function.1 The VWF:RCo, although a measure of VWF’s function in binding platelets, is problematic due to a high coefficient of variation, both intra- and inter-laboratory, and the fact that it is driven by a nonphysiologic activator of VWF.2-4 Although shear stress initiates the interaction of VWF and platelets in vivo, laboratory assays typically assess only static interactions. Low VWF levels are a not-uncommon finding, particularly in those with blood group O.5 Diagnosis of VWD, however, should not rely solely on laboratory phenotype.6

We have recently reported that a sequence variation in the A1 domain of VWF, p.D1472H (D1472H; c.4414G>C), is associated with decreased VWF:RCo/VWF:Ag levels in a population of healthy controls.7 This finding is attributed to changes in the ristocetin binding domain that occur as a consequence of the D1472H amino acid substitution and does not seem to interfere with VWF binding to platelets.7

Sequence variations in VWF are common, particularly in African Americans.8 Many patients with type 1 VWD lack a genetic mutation in VWF, particularly those whose VWF:Ag levels are >20-30 IU/dL.9,10 Therefore it is logical to propose that common sequence variations such as the D1472H may have an impact on bleeding in this particular group of patients. Our previous work demonstrated that the D1472H sequence variation was present in 63% of African American and 17% of Caucasian healthy controls but was not associated with an increased bleeding score.7 This report explores the significance of the effect of the D1472H sequence variation on bleeding score in a group of subjects with type 1 VWD enrolled in the Zimmerman Program for the Molecular and Clinical Biology of VWD (Zimmerman Program).

Study design

Subjects with a preexisting diagnosis of type 1 VWD were enrolled in the Zimmerman Program from multiple centers across the US following informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.11 The Institutional Review Boards at each enrolling center approved this study. Entry criteria consisted of a diagnosis of VWD as made by their treating physician. VWF:Ag, VWF:RCo, VWF collagen binding (VWF:CB), factor VIII activity, and multimer distribution were performed at the BloodCenter of Wisconsin Hemostasis Reference Laboratory as previously described.7 VWF sequencing was performed for all coding regions and intron/exon boundaries.8 Bleeding scores were calculated using the scoring system developed by Tosetto and colleagues.12 Statistical analysis was performed using the program Stata (StataCorp LP). Comparisons between groups were tested using the Mann-Whitney U test, because they were not normally distributed.

Results and discussion

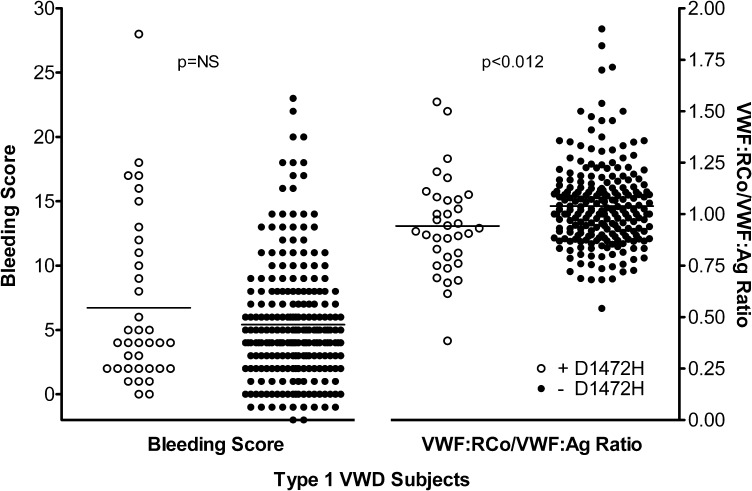

A total of 277 type 1 VWD subjects were categorized based on the presence or absence of the D1472H sequence variation. All had VWF:Ag <60 IU/dL at the time of enrollment in the Zimmerman Program. Of these, 36 were positive for D1472H (either heterozygous or homozygous for 1472H) and 241 were homozygous for the 1472D allele. Of the African American type 1 VWD subjects, 56% had the D1472H sequence variation, similar to the frequency previously observed in healthy African American controls.7 The mean VWF:RCo/VWF:Ag ratio in the subjects with D1472H was 0.94, while the mean ratio in the subjects without D1472H was 1.04 (Figure 1). This difference was statistically significant (P < .012) and similar to the difference seen in the healthy control population previously reported.7

Figure 1.

Scatterplot of bleeding scores and VWF:RCo/VWF:Ag ratios for type 1 VWD subjects. Bleeding scores are plotted on the left y-axis and VWF:RCo/VWF:Ag ratios are plotted on the right y-axis. White circles represent subjects with the D1472H sequence variation and black circles represent subjects without the D1472H sequence variation.

No difference was seen in the bleeding score. Those subjects with D1472H had a mean bleeding score of 6.7, while those without D1472H had a mean bleeding score of 5.4 (P = NS). No difference was seen in factor VIII activity (P = NS), although there was a statistically significant difference in VWF:Ag (P < .036), VWF:RCo (P < .001), and VWF:CB (P < .01). These data are summarized in Table 1. No correlation, either positive or negative, was observed between the bleeding score and VWF:RCo/VWF:Ag ratio. No difference in blood group was observed, with ∼75% of all type 1 VWD subjects noted to have blood group O, regardless of D1472H status.

Table 1.

VWF laboratory test results and bleeding scores for type 1 VWD subjects with and without D1472H

| Type 1 VWD subjects | D1472H (n = 36) |

No D1472H (n = 241) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± 1 SD | Median | Interquartile range | Mean ± 1 SD | Median | Interquartile range | P value | |

| FVIII activity, IU/dL | 56 ± 20 | 56 | 48-72 | 55 ± 22 | 54 | 42-73 | NS |

| VWF:Ag, IU/dL | 32 ± 13 | 34 | 24-41 | 36 ± 15 | 39 | 26-48 | P < .036 |

| VWF:RCo, IU/dL* | 29 ± 10 | 30 | 23-37 | 37 ± 15 | 39 | 27-47 | P < .001 |

| VWF:RCo/VWF:Ag ratio* | 0.94 ± 0.24 | 0.92 | 0.79-1.07 | 1.04 ± 0.20 | 1.02 | 0.90-1.13 | P < .012 |

| VWF:CB, IU/dL | 34 ± 13 | 37 | 22-42 | 41 ± 18 | 46 | 29-55 | P < .01 |

| Bleeding score | 6.72 ± 6.5 | 4 | 2-11 | 5.44 ± 4.6 | 5 | 2-7 | NS |

22 type 1 subjects (2 with D1472H and 20 without D1472H) had a VWF:RCo <10 IU/dL (the lower limit of detection in our laboratory); therefore, a ratio was unable to be calculated and those subjects were excluded from analysis. Inclusion of these subjects using a VWF:RCo value of 5 IU/dL did not change the statistical significance of the results.

Additional sequence variations were found in 81% of the subjects with D1472H and 40% without D1472H, many previously reported in type 1 VWD. The most common sequence variants identified were p.Y1584C in 19 subjects, p.R924Q in 12 subjects, and c.3108+5G>A in 10 subjects. The remainder of the type 1 subjects had no mutations or significant sequence variations found in the coding region of VWF. Although lower VWF:Ag, VWF:RCo, and VWF:CB levels were observed in the group with D1472H, the presence of additional sequence variations in many subjects confounds interpretation of these results. Those subjects with D1472H and no other sequence variation had VWF levels similar to those observed in the group without D1472H. No increase in bleeding score was seen for the subjects with D1472H, despite the higher frequency of mutations or novel sequence variations observed. This would suggest that the presence of D1472H did not influence the diagnosis of type 1 VWD, nor was it associated with an increase in bleeding symptoms.

There are several limitations to this study, however, that preclude definite conclusions regarding the effect of the D1472H sequence variation on the clinical phenotype of VWD. The Zimmerman Program subjects all had preexisting diagnoses of type 1 VWD as determined by their treating physician, but strict diagnostic criteria were not required for the multicenter study entry. The frequency of D1472H varies between races present in our study population. Therefore, there may be some selection bias introduced due to differences in rates of presentation at study centers or of VWD diagnosis between those with D1472H and those without D1472H. The Zimmerman Program type 1 VWD subjects were taken from the primary and secondary study centers without regard for race, but local differences in diagnosis of VWD cannot be excluded. Bleeding scores may also not fully reflect the array of hemorrhagic symptoms experienced by patients, and thus reliance on a quantitative bleeding score may not completely rule out clinically significant differences in bleeding phenotype.

Based on the data from the Zimmerman Program, there does not appear to be a significant association of the D1472H sequence variation with bleeding symptoms. Although only a prospective analysis could conclusively confirm this suspicion, our results support the conclusion that D1472H is a benign sequence variation rather than a physiologic risk factor for bleeding. Presence of the D1472H sequence variation, however, does not preclude the diagnosis of type 1 VWD, as demonstrated by Crawford and colleagues.13 Improved assays of VWF function, such as those under development using GPIb in the absence of ristocetin, would help alleviate this problem.14,15 This may have implications for improving the diagnosis and classification of VWD.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the subjects, physicians, and staff involved in the Zimmerman Program.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health program project grant HL081588 (R.R.M.) and K08 grant HL102260 (V.H.F.). This work was also supported by the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health through grant number 8UL1TR000055. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: V.H.F., K.D.F., J.C.G., S.L.H., and R.R.M. designed the research project; K.D.F., P.A.C., and B.R.B. collected data; R.G.H. performed the statistical analyses; V.H.F., K.D.F., J.C.G., S.L.H., T.C.A., A.L.D., J.A.D.P., W.K.H., D.L.B., C.L., J.M.L., M.V.R., A.D.S., and R.R.M. analyzed results; and V.H.F., K.D.F., and R.R.M. wrote the paper. All authors had full access to the data and edited the final paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: J.C.G. is a consultant to Baxter and CSL Behring. C.L. is a consultant to Baxter and CSL Behring. R.R.M. is a consultant to GTI Diagnostics, Inc., Baxter, CSL Behring, and AstraZeneca. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Veronica H. Flood, Comprehensive Center for Bleeding Disorders, 8739 Watertown Plank Rd, PO Box 2178, Milwaukee, WI 53201-2178; e-mail: vflood@mcw.edu.

References

- 1.Nichols WL, Hultin MB, James AH, et al. von Willebrand disease (VWD): evidence-based diagnosis and management guidelines, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Expert Panel report (USA). Haemophilia. 2008;14(2):171–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2007.01643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kitchen S, Jennings I, Woods TA, Kitchen DP, Walker ID, Preston FE. Laboratory tests for measurement of von Willebrand factor show poor agreement among different centers: results from the United Kingdom National External Quality Assessment Scheme for Blood Coagulation. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2006;32(5):492–498. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-947863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meijer P, Haverkate F. An external quality assessment program for von Willebrand factor laboratory analysis: an overview from the European concerted action on thrombosis and disabilities foundation. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2006;32(5):485–491. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-947862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sadler JE. Redeeming ristocetin. Blood. 2010;116(2):155–156. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-276394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gill JC, Endres-Brooks J, Bauer PJ, Marks WJ, Jr, Montgomery RR. The effect of ABO blood group on the diagnosis of von Willebrand disease. Blood. 1987;69(6):1691–1695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sadler JE. Von Willebrand disease type 1: a diagnosis in search of a disease. Blood. 2003;101(6):2089–2093. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-09-2892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flood VH, Gill JC, Morateck PA, et al. Common VWF exon 28 polymorphisms in African Americans affecting the VWF activity assay by ristocetin cofactor. Blood. 2010;116(2):280–286. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-249102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bellissimo DB, Christopherson PA, Flood VH, et al. VWF mutations and new sequence variations identified in healthy controls are more frequent in the African-American population. Blood. 2012;119(9):2135–2140. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-10-384610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goodeve A, Eikenboom J, Castaman G, et al. Phenotype and genotype of a cohort of families historically diagnosed with type 1 von Willebrand disease in the European study, Molecular and Clinical Markers for the Diagnosis and Management of Type 1 von Willebrand Disease (MCMDM-1VWD). Blood. 2007;109(1):112–121. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-020784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.James PD, Notley C, Hegadorn C, et al. The mutational spectrum of type 1 von Willebrand disease: Results from a Canadian cohort study. Blood. 2007;109(1):145–154. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-021105.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flood VH, Gill JC, Christopherson PA, et al. Comparison of type I, type III and type VI collagen binding assays in diagnosis of von Willebrand disease. J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10(7):1425–1432. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2012.04747.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tosetto A, Rodeghiero F, Castaman G, et al. A quantitative analysis of bleeding symptoms in type 1 von Willebrand disease: results from a multicenter European study (MCMDM-1 VWD). J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4(4):766–773. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crawford JA, Dietrich JE, Hui SKR, Friedman KD, Mahoney D, Lakshmi V. Patients with bleeding phenotype and von Willebrand exon 28 polymorphism D1472H: a retrospective analysis at a single institution. Blood. 2012;120(21):Abstract 100. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hulstein JJ, de Groot PG, Silence K, Veyradier A, Fijnheer R, Lenting PJ. A novel nanobody that detects the gain-of-function phenotype of von Willebrand factor in ADAMTS13 deficiency and von Willebrand disease type 2B. Blood. 2005;106(9):3035–3042. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flood VH, Gill JC, Morateck PA, et al. Gain-of-function GPIb ELISA assay for VWF activity in the Zimmerman Program for the Molecular and Clinical Biology of VWD. Blood. 2011;117(6):e67–e74. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-08-299016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]