Abstract

Background: Helplines are a significant phenomenon in the mixed economy of health and social care. Given the often anonymous and fleeting nature of caller contact, it is difficult to obtain data about their impact and how users perceive their value. This paper reports findings from an online survey of callers contacting Samaritans emotional support services. Aims: To explore the (self-reported) characteristics of callers using a national suicide prevention helpline and their reasons given for contacting the service, and to present the users’ evaluations of the service they received. Methods: Online survey of a self-selected sample of callers. Results: 1,309 responses were received between May 2008 and May 2009. There were high incidences of expressed suicidality and mental health issues. Regular and ongoing use of the service was common. Respondents used the service for complex and varied reasons and often as part of a network of support. Conclusions: Respondents reported high levels of satisfaction with the service and perceived contact to be helpful. Although Samaritans aims to provide a crisis service, many callers do not access this in isolation or as a last resort, instead contacting the organization selectively and often in tandem with other types of support.

Keywords: helplines, Samaritans, suicide, mental health, callers’ perspectives

Background

Samaritans was established in 1953 and is one of the oldest telephone helpline services in the UK. Helplines have undergone rapid global proliferation since the 1950s (De Leo, Dello Buono, & Dwyer, 2002; Fleischmann et al., 2008; Hall & Schlosar, 1995; Jianlin, 1995; Mental Health Helplines Partnership, 2003; Miller, Coombs, Leeper, & Barton, 1984): Some have been established through statutory services as an adjunct to professional medical or psychiatric care (Evans, Morgan, & Hayward, 2002; Fleischmann et al., 2008; King, Nurcombe, Bickman, Hides, & Reid, 2003), whereas many others operate within the voluntary sector (Mishara, 1997; Mishara et al., 2007; Wakeling, 1999). In recent years traditional telephone support has been extended to encompass new technologies such as internet forums, e-mail, and text messaging (Lipczynska, 2009). The range of topics covered and the groups targeted by helplines is striking: Some are established for people experiencing specific problems, from health issues to difficulties with bereavement, gambling, or smoking cessation (Jianlin, 1995; Potenza et al., 2001; Prout et al., 2002; Wakeling, 1999), while others support specific demographic groups, including children, students, parents, and older people (Boddy, Smith, & Simon, 2004; Fukkink & Hermanns, 2009; Harrison, 2000; Thompson & Thompson, 1974). The remit and approach of helplines varies widely (Mishara et al., 2007): Some offer advice (Shekelle & Roland, 1999), while others provide counseling on a specific issue (Prout et al., 2002) or provide support through listening (Thompson & Thompson, 1974) or befriending services (Cattan, Kime, & Bagnall, 2009).

Samaritans is a volunteer-based crisis service aiming to support callers on a short-term basis throughout an episode of crisis or trouble. Samaritans is singular in focusing on suicide and acceptance of callers’ need to explore suicidal feelings and intentions within the security of an anonymous, confidential, nondirective, and nonjudgmental setting (Samaritans, 2003, 2011). However, the organization has made its services available to anyone experiencing emotional difficulty or distress and in the past has taken a notably inclusive attitude in allowing callers to define their own need and to determine how they use the service. Samaritans assess the majority of calls to be from people who are distressed, albeit not suicidal (Samaritans, 2011).

The efficacy of Helpline is difficult to establish (Leenaars & Lester, 2004; Miller et al., 1984; Mishara et al., 2007) especially when, as with the Samaritans, contact with callers may be brief and anonymous, with little scope for caller feedback or follow-up of impact. Some evidence suggests that helplines can improve the short-term mental state of callers, including a reduction in suicidal ideation and intent (Guo, Scott, & Bowker, 2003; Mann et al., 2005; Guo & Harstall, 2004). Given the diversity of behavioral, psychological, and socioeconomic factors associated with risk of suicide (Appleby et al., 1999; Barbe, Bridge, Birmaher, Kolko, & Brent, 2004; Cutcliffe & Stevenson, 2007; Eagles, Carson, Begg, & Naji, 2003; Eldrid, 1988; Higgitt, 2000; Maris, 2002; Nock et al., 2008; Varah, 1988), establishing longer term effects or contributing contribute to suicide prevention is more difficult (Kalafat, Gould, Munfakh, & Kleinman, 2007; Leitner, Barr, & Hobby, 2008; Mead, Lester, Chew-Graham, Gask, & Bower, 2010; Mishara et al., 2007). The sheer complexity of factors influencing suicidal action at the societal and individual levels may preclude an “objective” assessment of whether helplines actually contribute to reducing suicide (Gunnell & Frankel, 1994; King et al., 2003; Mishara, 1997; Miller et al., 1984). Nevertheless, user assessment is an important service outcome. The present study extends the previously limited knowledge and understanding of the characteristics of Samaritans callers, their reasons for contact, and their experience and assessment of the service.

Methods

This paper presents findings from an online survey that was one component of a 2-year, independent, mixed-method evaluation of Samaritans telephone and e-mail support service (Pollock, Armstrong, Coveney, & Moore, 2010). The confidential and anonymous service Samaritans provides to callers posed a particular challenge to recruiting respondents. It was not possible to identify and directly contact people who had used Samaritans, so alternative ways of inviting callers to participate in the study were developed. A project website promoted the study and hosted an online questionnaire. The internet enabled contact to be established with a wide range of callers, while also allowing respondents to maintain their anonymity (Flick, 2009; Murthy, 2008). To reach callers lacking access or familiarity with the internet the study was advertised through local and national media and community networks. A paper copy of the questionnaire was available upon request, but was returned by only two respondents. The recruitment strategy relied on callers becoming aware of the research and actively volunteering to participate in the study.

Data were analyzed using the statistical package SPSS version 16.0. Descriptive statistics summarized the characteristics of the survey respondents as well as their use of, experience, and assessment of the service. Categorical data were described using frequency counts and percentages. Ordinal data were summarized using the median and lower and upper quartiles. Since this was an exploratory study, gathering information on the needs and opinions of Samaritans callers with no specific hypotheses to be tested, comparisons between groups were made informally without the use of hypothesis tests.

The online questionnaire included a number of open-ended questions. Responses to these amounted to a very substantial body of qualitative data, which will be the focus of a subsequent publication. The present paper focuses only on findings from the quantitative part of the survey.

Results

Between May 2008 and May 2009, 1,396 respondents completed the online questionnaire. After eliminating duplicate data, incomplete datasets (where no feedback on the service was given), and nongenuine or inconsistent responders, we included 1,309 (93.8%) respondents in the data analysis. Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the 1309 survey respondents. The majority (77.9%) were female, of white British or Irish ethnicity (82.3%, n = 1049), heterosexual (76.2%), single (62.2%) and living with other people (79.1%), most commonly with their parents (36.1%). Almost 80% of respondents were aged between 16 and 44 and approximately two thirds were UK residents at the time they took the survey (67.8%). Three quarters (75.2%) of the respondents were in education or employment, with 23.6% employed full time. Around one fifth (21.8%) reported having a disability, and just over one third (34.2%) said that they were taking medication for a mental health-related problem when last contacting Samaritans. Most (80.4%) were still taking this medication when they completed the survey. The duration of medication intake ranged from less than 1 month to over 35 years. Most survey respondents (89.3%) had last contacted the Samaritans within the last year. Just over half (51.7%) had done so within the last month.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of survey respondents.

| Characteristic | No. | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Notes. Missing data for each question: 11.7% (n = 22); 20.6% (n = 8); 32.8% (n = 36); 42.9% (n = 38); 52.1% (n = 27); 64% (n = 52); 74% (n = 53); 85.6% (n = 73). | ||

| Sex1 | ||

| Male | 285 | 22.1 |

| Female | 1002 | 77.9 |

| Age group2 | ||

| < 16 | 131 | 10.1 |

| 16–24 | 470 | 36.1 |

| 25–35 | 253 | 19.4 |

| 36–44 | 188 | 14.5 |

| 45–54 | 181 | 13.9 |

| 55–64 | 67 | 5.1 |

| 65–74 | 8 | 0.6 |

| 75–84 | 1 | 0.1 |

| ≥ 85 | 2 | 0.2 |

| Marital status3 | ||

| Married/living with partner | 299 | 23.5 |

| Divorced/separated | 152 | 11.9 |

| Single | 792 | 62.2 |

| Widowed | 30 | 2.4 |

| Living arrangements4 | ||

| Alone | 266 | 20.9 |

| With others | 1005 | 79.1 |

| UK resident5 | ||

| Yes | 869 | 67.8 |

| No | 413 | 32.2 |

| Sexuality6 | ||

| Heterosexual | 958 | 76.2 |

| Bisexual | 116 | 9.2 |

| Gay/lesbian | 72 | 5.7 |

| Unknown | 111 | 8.8 |

| Current occupational status7 | ||

| Employed full-time | 296 | 23.6 |

| Employed part-time | 100 | 8.0 |

| Self-employed | 38 | 3.0 |

| University/college student | 252 | 20.1 |

| Unemployed | 93 | 7.4 |

| Unable to work due to health problems | 154 | 12.3 |

| On parental leave | 4 | 0.3 |

| Parenting/homemaker | 34 | 2.7 |

| Retired/Semiretired | 36 | 2.8 |

| Carer | 4 | 0.3 |

| At school | 201 | 16 |

| Other | 44 | 3.5 |

| Disability8 | ||

| No | 967 | 78.2 |

| Yes | 269 | 21.8 |

Reasons for Contacting Samaritans

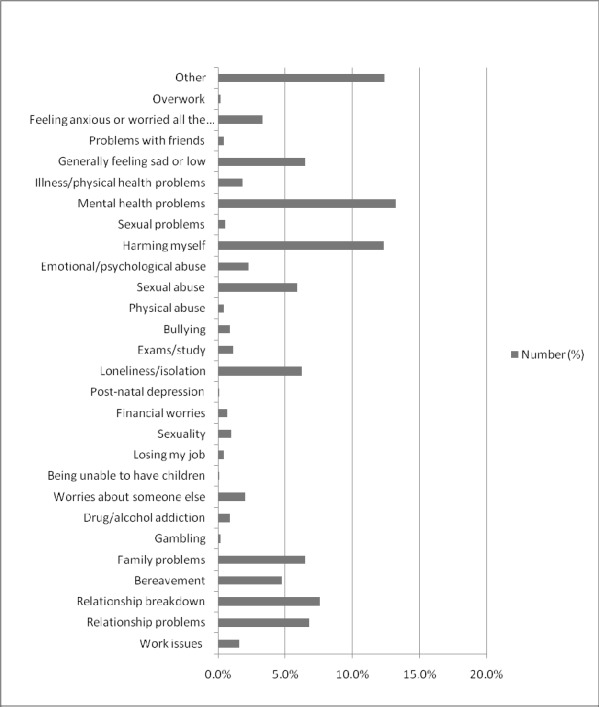

Survey respondents were asked to provide details of their main reason for last contacting Samaritans by selecting one of 28 predefined options (Figure 1 ). The most common reasons were mental health problems (13.2%, n = 153), self-harm (12.3%, n = 142), relationship breakdown (7.6%, n = 88), relationship problems (6.8%, n = 79), and family problems (6.5%, n = 75). A further 6.5% (n = 75) of participants stated their main reason to be because they were feeling generally sad or low, and 6.2% (n = 72) of respondents contacted because they were feeling isolated or lonely. Sexual abuse was the main reason given by 5.9% (68) and bereavement by 4.7% (n = 55) of respondents.

Figure 1. Main reason for last contacting Samaritans.

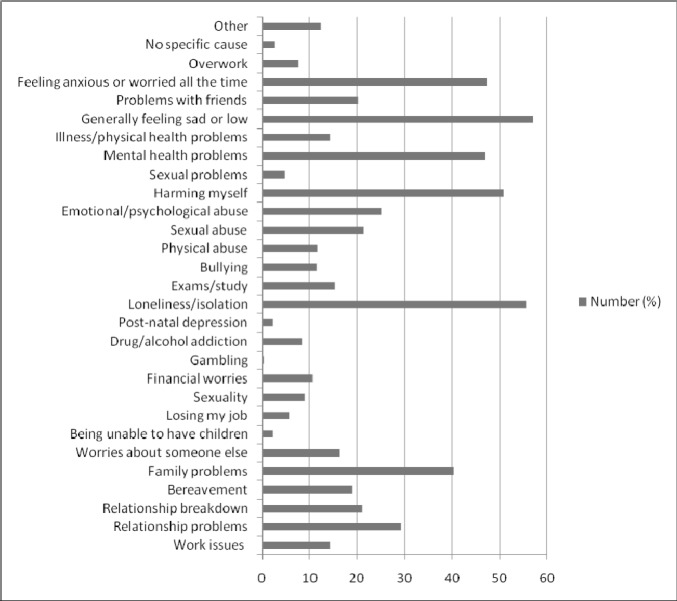

Just over half (54%, n = 593) of the survey respondents had contacted Samaritans more than once. The distribution of the last contact in this group was similar to that of respondents who had only contacted Samaritans on more than one occasion. In both groups approximately half had contacted Samaritans less than a month ago (49.4% and 52.4% for once only and multiple users, respectively). Respondents were asked to select all relevant reasons for multiple contacts with Samaritans (Figure 2 ): 57% (n = 338) reported feeling generally sad or low, 55.5% (n = 329) felt lonely and isolated, and 47.2% (n = 280) felt anxious or worried all the time. Other options frequently selected for previous contacts were self-harm (50.9%, n = 302), mental health issues (47%, n = 279), family problems (40.3%, n = 239), and relationship problems (29.3%, n = 174). Other main reasons for contact selected by 12.6% (n = 144) of respondents included stress, pain, guilt, anger, needing human contact, and feeling lost.

Figure 2. Reasons for past contact.

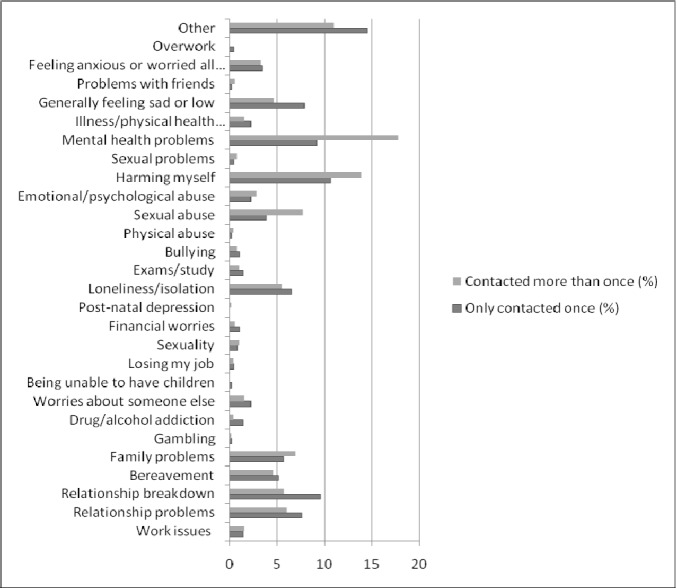

A higher proportion of single contacts was from people feeling generally sad or low or reporting relationship problems compared to those who had used the service more than once (Figure 3 ). A higher proportion of repeat callers reported their main reason for contact was related to mental health issues, self-harm, and sexual abuse. Similar frequencies of other issues, such as loneliness and isolation, bereavement, and family problems were reported by both groups of respondents.

Figure 3. Comparing main reason for last contact between those who have only contacted once and those that have used the service more than once.

Perceived Impact of Contact with Samaritans on Feelings

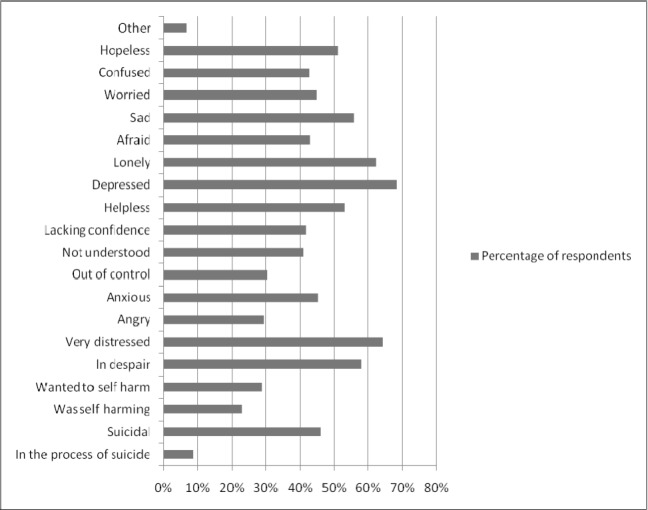

In describing how they were feeling before their last contact with Samaritans, respondents typically specified their feeling depressed (68.3%, n = 894), very distressed (64.1%, n = 839), lonely (62.1%, n = 813), in despair (58.1%, n = 761), sad (55.7%, n = 729), helpless (53%, n = 694), and hopeless (51.1%, n = 669); a majority selected more than one option from the list. Additionally, 46.3% (n = 606) of respondents reported feeling suicidal before the last contact, and 8.6% (n = 113) indicated that they had called while in the process of suicide (Figure 4 ).

Figure 4. Feelings before last contact.

Respondents rated how they felt at the end of their last contact with Samaritans on a 10-point semantic differential scale (e.g., ranging from unhappy to happy). The median scores (MS) were calculated to indicate the average score given on this scale across the sample. Scores higher than the midpoint (5) indicate a positive change, and scores lower than this indicate a negative change in feelings1 (Table 2 ). Overall, respondents reported feeling more positive than negative after their last contact with Samaritans. The highest MSs were for feeling listened to and feeling understood. Despite the Samaritans’ policy of offering nondirective and nonjudgmental support as a means of enabling callers to review and explore options, many respondents considered they had been given advice, and that a solution had been found for their problems. Respondents tended to report feeling less suicidal, alone, afraid, and anxious and more hopeful, supported, and wanting to live after contact. MS for the remaining variables indicated that, after contact with Samaritans, participants felt neither more or less confident, happy or cared for. Additionally, respondents reported feeling more depressed than not.

Table 2. Respondent’s feelings at the end of last contact with Samaritans.

| Feelings | Endpoints of scale (1–10): | Median score [Interquartile range] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10 | ||

| Note. Missing data for each question: 111.5% (n = 150); 215.4% (n = 202); 312.3% (n = 161); 416.3% (n = 213); 516,4% (n = 215); 614.5% (n = 190); 717% (n = 223); 814.7% (n = 193); 916.2% (n = 212); 1015% (n = 196); 1116.1% (n = 211); 1215% (n = 197); 1315.4% (n = 202); 1414.7% (n = 193); 1512.8% (n = 168). | |||

| Listened to1 | Not listened to | Listened to | 9 [7,10] |

| Suicidal2 | Suicidal | Not suicidal | 7 [4,10] |

| Lonely3 | Alone | Not alone | 6 [4,8] |

| Afraid4 | Afraid | Unafraid | 6 [4,8] |

| Anxious5 | Anxious | Not anxious | 6 [4,8] |

| Happy6 | Unhappy | Happy | 5 [2,6] |

| Confident7 | Not confident | Confident | 5 [3,6.25] |

| Understood8 | Not understood | Understood | 7 [4,9] |

| Hopeful9 | Hopeless | Hopeful | 6 [3,7] |

| Depressed10 | Depressed | Not depressed | 4 [2,7] |

| Wanted to live11 | Don’t want to live | Want to live | 6 [3,9] |

| Cared for12 | Not cared for | Cared for | 5 [2,6] |

| Supported13 | Not supported | Supported | 6 [3,9] |

| Solution had been found14 | No solution | Solution found | 7 [5,9] |

| Given advice15 | No advice | Advice given | 8 [5,10] |

A question about how respondents were feeling overall after their last contact with Samaritans compared to how they felt before the contact on a scale of 1 (worse) to 10 (better) was scored highly (MS 7 [5,8]) indicating that contact with Samaritans was felt to have an immediate positive effect. This assessment did not differ markedly between males (MS 7 [5,9]) and females (MS 7 [5,8]). All age groups between 16 and 54 had a MS of 7. Those under 15 and between 65–74 had a higher MS of 8, and those 55–64, 75–84, and 85 and over all had lower MS of 5, 6, and 1.5, respectively. However, with the exception of those under 15, these age groups had considerably fewer participants than those between 16–54, making the data less reliable (Table 1).

Respondents were asked to indicate how they felt at the time of last contact compared to when they completed the survey (i.e., the present) in order to provide some indication of change or stability of mood between these two timepoints. In general, callers reported feeling slightly better when they completed the survey compared to immediately after their last contact with Samaritans (MS 6[3,8]). This did not vary greatly according to how recent this had been. Respondents contacting within the preceding month and those last in touch 7–12 months before had a MS of 6, and those last contacting between 1 and 6 months previously had a MS of 5. Responses from people whose last contact had been more than a year ago were more variable and less reliable due to the smaller number of respondents in this group. How respondents felt when completing the online questionnaire compared to at the end of last contact with Samaritans did not differ markedly according to gender: Males and females both had a MS of 6.

Callers’ Assessments of Their Experiences of Samaritans’ Services

Perceived Helpfulness of Service

Using a 10-point semantic differential scale (1 = no help at all to 10 = very helpful), respondents were asked to indicate how helpful they had found Samaritans at the time of last contact. Those who had used the service more than once were also asked to give an overall perception of how helpful they thought contact with Samaritans usually was. Responses were generally positive: The MS for helpfulness of last contact was 7 [5, 9], and for overall perception of helpfulness it was 8 [7, 10].

Experience of Contacting Samaritans

Sixty-two percent (n = 673) of respondents felt they had always been listened to, but a further 30.4% (n = 329) reported that they had sometimes felt listened to. The remaining responses indicated that 3.1% (n = 33) of respondents did not feel listened to very often, and 4.3% (n = 46) did not feel listened to at all. Overall, respondents were satisfied with length of time taken for them to receive a response from Samaritans. However, there was variation according to the method of contact used. Those who had phoned or visited a branch tended to report higher levels of satisfaction with the length of response time than those who had used e-mail or text message (Table 3 ).

Table 3. Satisfaction with length of time for response.

| Level of satisfaction with speed of response1 | Method of contact used | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Telephone2 | E-mail3 | Text message4 | Postal letter5 | Visit6 | ||||||

| N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | |

| Notes.1Based on the 593 respondents who contacted Samaritans more than once. Missing data: 24.2% (n = 15); 32.5% (n = 9); 41.5% (n = 1); 55.9% (n = 1); 69.6% (n = 4). | ||||||||||

| Very satisfied | 175 | 51.2 | 128 | 36.3 | 16 | 29.6 | 9 | 56.2 | 52 | 58.4 |

| Moderately satisfied | 46 | 13.5 | 83 | 23.5 | 13 | 24.1 | 3 | 18.8 | 13 | 14.6 |

| Fairly satisfied | 53 | 15.5 | 78 | 22.1 | 12 | 22.2 | 2 | 12.5 | 14 | 15.7 |

| Not satisfied | 19 | 5.6 | 17 | 4.8 | 8 | 14.8 | 1 | 6.2 | 5 | 5.6 |

| Not sure/varies | 49 | 14.3 | 47 | 13.3 | 5 | 9.3 | 1 | 6.2 | 5 | 5.6 |

Reactions to Being Asked About Suicide During Last Contact

It is Samaritans policy for volunteers to enquire about suicidal feelings at every contact. However, only 59% (n = 655) of respondents reported being asked during their last contact with Samaritans whether they were feeling suicidal. The percentage was relatively consistent (at around 70% of callers) when comparing methods of contact, with the exception of those who had used the e-mail service where only 50% (n = 317) of respondents reported being asked about feeling suicidal. Respondents were asked how they felt about this question. Responses were grouped into four categories: positive feelings, negative feelings, feeling embarrassed or surprised, and not sure2 Of those who had been asked the suicide question, 88.2% (n = 578) expressed how they felt, with 44.5% (n = 257) selecting more than one category option. Just over half (51%, n = 376) of all responses indicated a positive reaction to being asked about suicide, and only 6.4% (n = 47) were negative. A further 16.5% (n = 122) were unsure of how they felt, and a quarter (26%, n = 192) of responses indicated that the respondents had felt embarrassed or surprised when the topic of suicide was brought up by volunteers. Respondents’ reactions to being asked about suicidal feelings did not vary extensively according to the main reason for contact.

Overall Perception of Service

Two-thirds (66%, n = 357) of respondents reported receiving a consistent level of service across multiple contacts. Approximately three quarters of respondents3 rated their overall perception of Samaritans services as “excellent” (31.8%, n = 268) or “good” (39.4%, n = 332). A further 14.6% (n = 123) rated the service as “reasonable,” 4.8% (n = 40) as “bad,” and 9.3% (n = 79) said it was “variable.” Most respondents did not recall what they had expected to happen when they first contacted Samaritans. Over one third (37.6%, n = 420) reported having no prior expectations, and 37.2% (n = 415) either did not know or could not remember what they had initially expected. Respondents were asked to rate their perceptions of the service they received from Samaritans compared to their expectations prior to first contact on a 10-point scale (1 = worse to 10 = better). Overall, respondents scored their perceptions of the service highly, giving a median score of 8 [5,9] This figure is based upon 1,061 responses and thus includes ratings from those who had not previously indicated that they had expectations of the service and those who were not sure what to expect. Among those who had indicated having expectations prior to using the service (25.2%, n = 281) the median was slightly lower (7 [4,9]).

The survey included a direct question about whether respondents thought Samaritans services could be improved. Approximately 40% (n = 408) of respondents provided suggestions for improvement. These were grouped into four main categories. Most commonly, respondents’ suggestions focused on practical issues having to do with use of the service (54.5%, n = 240) such as the incorporation of new technologies (e.g., webchat), the length of contacts, and reducing the cost of calling. Ways to improve interactions between caller and volunteer (43.8%, n = 192) were also commonly raised (e.g., use of silence by volunteers, methods of beginning and ending the call). Respondents also proposed changes to the way volunteers are recruited and trained (7%, n = 32) and that the service could be improved through the generally wider promotion of the organization (5.9%, n = 26)4.

Contact with Other Services

Of the survey respondents, 38% (n = 425) reported being in touch with other services when they last contacted Samaritans, with 77.6% (n = 330) thereof providing further details of the service(s) they used and rating their helpfulness in comparison to Samaritans. 51% (n = 169) reported contacting one other service about the same issue they had called Samaritans about, 27.9% (n = 92) were in contact with two other services, 15.2% (n = 50) with three other services, 3.6% (n = 12) with four, and 2.1% (n = 7) with five other services. A wide range of other services and organizations was reported, including specialized and professional services as well as more informal organizations ranging from self-help groups to exercise clubs and religious groups. Other services were grouped into three categories: voluntary organizations and self-help groups, statutory and other professional services, and alternative services (Table 4 ).

Table 4. Comparison with other services.

| Service | How helpful service was in comparison to Samaritans1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| N | (%) | ||

| Note.138.3% (n = 425) of the survey respondents reported that they were in touch with other services at the time when they were in last contact with Samaritans. The data presented in this table are from 330 (77.6%) of these respondents who provided further details of the service(s) they used and rated how helpful they thought these other services had been in comparison to their contact with Samaritans. | |||

| Voluntary | More | 25 | 29.8 |

| Equal | 31 | 36.9 | |

| Less | 28 | 33.3 | |

| Statutory | More | 72 | 26.1 |

| Equal | 101 | 36.6 | |

| Less | 103 | 37.3 | |

| Alternative | More | 9 | 34.6 |

| Equal | 12 | 42.2 | |

| Less | 5 | 19.2 | |

Statutory Services

Of the other services used by callers in support of the same issue that they called Samaritans about, statutory services emerged as by far the most frequent, being specified by 84.2% (n = 278) of those who were in contact with other services at the time of last contacting Samaritans. GPs were most frequently mentioned (n = 137), with therapist or counselor (n = 97), community mental health teams (n = 86), and psychiatrists or psychologists (n = 84) also commonly specified. Just over a quarter of those who were in contact with statutory services rated this contact as more helpful than Samaritans. However, 37.3% of these respondents considered their contact with statutory services to be less helpful than their contact with Samaritans (Table 4).

Voluntary Organizations

Sixty-two different voluntary organizations were listed by 27% (n = 89) of callers who reported contact with other agencies. MIND, Childline, Victim Support, and National Self-harm Network were most frequently mentioned. Respondents’ opinions about the helpfulness of other voluntary organizations in comparison to Samaritans were divided fairly evenly, with 36.9% considering other voluntary services to be of equal helpfulness to Samaritans (Table 4).

Alternative Services

Contact with alternative services, including church groups, alternative therapists (e.g., acupuncturist, holistic healer), and exercise groups (e.g., yoga) was mentioned by 7.9% (n = 26) of respondents who were in touch with other services at the point of last contact with Samaritans. Seven respondents listed friends or family members as another service they were accessing. The majority of respondents perceived alternative sources of support to be either equal to or more helpful than Samaritans. Only 19.2% rated these other services of support as less helpful than Samaritans (Table 4).

Discussion

Samaritans aims to provide an anonymous, confidential, and nonjudgmental space for callers to express emotions, appraise their options, and particularly to explore suicidal feelings and intentions. There is a general policy of asking about suicide at every contact. Over a quarter of those who responded to the survey said they were not asked whether they were feeling suicidal during their last contact. Just over half of the survey responses indicated a positive reaction to being asked about suicidal feelings, whereas a substantial minority reported negative feelings including embarrassment or being surprised when the topic of suicide was raised. The most recent annual summary by Samaritans (2011) of contacts based on volunteer logging and assessment of calls indicates that 20.3% (554,715) of dialog contacts (the majority of which are by phone) were assessed by volunteers to involve callers expressing suicidal feelings during the contact. This figure was considerably higher in the relatively much smaller numbers of e-mail (42.9%: 80,905) and SMS text messages (52.2%: 88,025). A further 22.6% of calls were considered to be abusive or inappropriate in some way (Samaritans, 2011). The majority of contacts are assessed to be from callers described as distressed but not expressing suicidal feelings (53.7%). Compared to the Samaritans figure for overall contacts, the survey respondents reported a higher incidence of suicidal feelings (46.3%) at the point of last contact. However, this figure may reflect the relatively younger age of these respondents and their greater preference for contact via text and e-mail, which contain a higher incidence of suicidal content. In this case the survey findings would be reasonably consistent with Samaritans data. However, the survey data contain a higher reporting of suicide in process during last contact with Samaritans (8.6%) compared to the annual estimates (0.6%) given in the Samaritans summary. The reason for this discrepancy is not clear. However, as was evident from the qualitative data sets collected alongside this survey data (Pollock et al., 2010), caller reports of “feeling” or even “being” suicidal referred to a very diverse spectrum of meaning and significance. “Feeling” suicidal bore very little relationship to a state of “being suicidal,” and even “being suicidal” did not necessarily relate to committed action to self-harm or suicide (Fairbairn, 1995; Holding, 1974; Mishara, 1997; Pollock et al., 2010).

A substantial proportion of survey respondents disclosed mental health issues, with around one third of all respondents reporting taking medication for a mental health-related problem when they last contacted the helpline, and almost half of those who had contacted Samaritans on more than one occasion cited mental health issues as their main reason for using the service in the past. Issues such as bereavement and work problems were not frequently stated reasons for contact. Experience of mental illness was more commonly given as a main reason for last contacting Samaritans by those who had used the service on more than one occasion compared to those who reported having used the service only once. This difference in reasons for contact between single and multiple users cannot be explained simply by how recently people had last contacted Samaritans, since the distribution of time since last contact was similar in both groups. Therefore, it was not that one-time callers were very recent users of the service, and that sufficient time had not elapsed to enable them to contact Samaritans on more than one occasion. The survey findings are consistent with other studies in reporting a heavy use of services by regular callers, a high proportion of whom report having mental-health problems of chronic and ongoing nature (Fakhoury, 2002; Hall & Schlosar, 1995; Mishara et al., 2007; Samaritans, 2004).

Over a third of survey respondents were in touch with other services at the time of last contacting Samaritans, indicating that in many cases callers do not access Samaritans in isolation or as a last resort. Rather, contact is made selectively with specific intent at particular times of need, often in tandem with other available sources and types of support. In addition, over half of the survey respondents had contacted Samaritans more than once. In line with other findings – and at variance with the stated aims and mission of the organization – this indicates that many callers value Samaritans as a source of ongoing support, rather than as a refuge in times of crisis (Hall & Schlosar, 1995; Mishara, 1997; Pollock et al., 2010).

The limited evidence available suggests that the impact of telephone crisis helplines is relatively small and short term (Gunnell & Frankel, 1994; Leitner et al., 2008; Mishara, 1997; Mishara et al., 2007). A recent systematic review of studies examined the effects of emotional support offered in the voluntary/community sector on depressive symptoms and found a mildly positive effect (Mead et al., 2010). The findings of the present study are consistent with the suggestion that a potential impact of voluntary sector support services such as Samaritans lies in providing a sense of “connectedness” for callers as a means of deflecting or reducing impulses to suicide or self-harm. However, previous research also suggests that such connectedness derives from the experience of relatively structured and enduring support, rather than short-term contact with crisis services (Mishara, 1997; Mishara et al., 2007). This is at odds with Samaritans’ intention of offering time-limited support for those experiencing crisis and the organizational commitment to nondirective active listening as the means of providing such support and to enable the caller to retain control and responsibility for decisions about their lives. The extent to which survey respondents (the majority) felt they had received advice during contact with Samaritans is a notable finding, in view of the organizational commitment to offering nondirective emotional support.

As reported by other studies of suicide helplines, various contact patterns were evident, ranging from callers who reported being or feeling suicidal to those with ongoing mental health problems who used Samaritans as part of their support network, to callers who were distressed but not suicidal (Hall & Schlosar, 1995; Mishara, 1997). Regardless of the degree to which their contact fell within the intended remit of the organization, respondents generally described the impact of Samaritans in positive terms. They reported feeling better after contact with the organization and rated the perceived helpfulness of the service highly. However, reflecting the complexity of the judgments involved in assessing an experience involving many facets, respondents also reported shortcomings and disappointments: Around two fifths of survey respondents gave suggestions as to how the service could be improved or better tailored to meet their needs.

Limitations

The findings reported in this paper present a substantial number of caller perspectives and provide a great deal of information about callers’ personal experiences and assessment of using Samaritans emotional support services not previously been available. The present study is in line with previous findings that callers fall broadly into two categories – acute and regular – and that regular callers are more often women and frequently suffer mental ill-health (Fakhoury, 2002; Hall & Schlosar, 1995; Holding, 1974; Mishara et al., 2007; Pollock et al., 2010; Samaritans, 2004). Analysis of the survey responses did not reveal any substantial differences between the reported experiences of male and female callers. However, those who completed the survey tended to be younger women using e-mail as their preferred means of contact. Consequently, the views and experiences of male callers may be underrepresented in the findings. The main drawback to hosting the survey online was that it was not possible to employ a sampling strategy or to recruit a “representative sample.” The self-selection of the survey respondents is an inevitable constraint, given the nature of Samaritans as an organization and the anonymity afforded to callers. The study incorporates the views and perspectives of a wide range of callers, but these cannot be considered representative of the wider population of persons who use Samaritans services. However, no information is available (from Samaritans or other sources) from which a representative sample of callers could be constructed, or which could have been used as a comparator for the respondents recruited in the present study. Samaritans do have reference data based on calls (Samaritans, 2011); rather, this is collected by branch volunteers who record only minimal information about each contact: duration, sex of caller, sometimes age if this was revealed, and a subjective assessment of suicidality. There is no way of verifying personal details that may be revealed during the call, or of constructing an accurate caller profile. The online survey was designed to capture the views and experiences of a broad range of users of Samaritans service rather than to investigate specific hypotheses and is therefore descriptive in nature.

Conclusion

Samaritans has an established position as one of the oldest and most respected helpline services in the UK. The high number of calls received by volunteers testifies to a significant level of expressed need for support by a diverse population of callers presenting with a wide range of troubles and concerns. However, the anonymous and confidential nature of the contact between callers and volunteers makes it difficult to establish an evidence base for the quality and effectiveness of the service or to develop awareness of callers’ expectations, experience, and assessment of contact with Samaritans, and their perceptions of how the service could be improved to better meet their needs in future. The difficulties involved in accurately assessing the impact and effectiveness of any kind of suicide prevention strategies, including telephone support lines, in terms of reduced incidence of death preempt any attempt at specifying to what extent Samaritans may contribute to this end (Bernburg, Thorlindsson, & Sigfusdottir, 2009; Barbe et al., 2004; Cavanagh, Lawrie, & Sharpe, 2003; Department of Health, 2002; Gunnell & Frankel, 1994; King et al., 2003; Leitner et al., 2008; Mishara, 1997). It was not the intention or purpose of this study to undertake such an assessment. However, the study findings extend insight into caller experiences of using Samaritans emotional support services, and the nature of the support received by callers and desired by different groups of user. They also point to routes for further service development in future.

Acknowledgments

The research reported in this paper was funded by Samaritans. The authors would like to thank all the Samaritans callers and volunteers who took part for their time and interest in the study. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily of Samaritans.

Biographies

Catherine Coveney has a background in medical sociology and science and technology studies. Her research interests lie in the sociology of mental health and illness, particularly in the use of new and existing technologies for “enhancement” purposes.

Kristian Pollock has a background in medical anthropology and has undertaken qualitative research in a range of health-care settings. Much of this work has focused on the contrasts between lay and professional perspectives of health and illness, and the role of information as a resource in dealing with serious ill health.

Sarah Armstrong has a background in medical statistics. She has designed and analyzed a wide range of health services research studies.

John Moore has a background in qualitative psychology and social interaction with a particular focus on workplace interactions. Recent work has focused on how institutional concerns such as advice provision and emotional support are managed by service providers.

Footnotes

We also report interquartile range figures here which show the distribution of scores around the MS. For evenly distributed data, the MS sits centrally between the upper and lower quartile scores. MS closer to the upper quartile indicate that the data were positively skewed and vice versa. Interquartile range scores closer to the median indicate that the scores given were grouped close together.

655 (59%) respondents were asked whether they felt suicidal. Of these 578 (88.2%) expressed their feelings about this. The number of responses reported is greater than the number of respondents who were asked whether they were feeling suicidal since respondents had the opportunity to express more than one type of feeling.

Responses from multiple users of Samaritans (n = 593). The number of responses is greater than the number of respondents since respondents were asked to express their perception of the service for each method of contact they had used (e.g., telephone, e-mail, face-to-face, SMS). Missing data: 6.6% (n = 39) respondents did not express their perception of the service.

The number of responses in this section is greater than the number of respondents since some respondents gave multiple suggestions for improvement.

References

- Appleby L., Shaw J., Amos T., McDonnell R., Harris C., McCann K., ... Parsons R. (1999). Suicide within 12 months of contact with mental health services: National clinical survey. British Medical Journal, 318, 1235–1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbe R. P., Bridge J., Birmaher B., Kolko D., & Brent D. A. (2004). Suicidality and its relationship to treatment outcomes in depressed adolescents. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 34, 44–55. doi 10.1521/suli.34.1.44.27768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernburg J. G., Thorlindsson T., & Sigfusdottir I. D. (2009). The spreading of suicidal behavior: The contextual effect of community household poverty on adolescent suicidal behavior and the mediating role of suicide suggestion. Social Science and Medicine, 68, 380–389. doi 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.10.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boddy J., Smith M., & Simon A. (2004). Evaluation of Parentline Plus (Home Office Online Report 33/04). Great Britain: Home Office. Retrieved from http://dera.ioe.ac.uk/8438/ [Google Scholar]

- Cattan M., Kime N., & Bagnall A.-M. (2009). Low-level support for socially isolated older people: An evaluation of telephone befriending. London, UK: Help the Aged. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh J. T. O., Lawrie S. M., & Sharpe M. (2003). Psychological autopsy studies of suicide: A systematic review. Psychological Medicine, 33, 395–405. doi 10.1017/S0033291702006943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutcliffe J. R., & Stevenson C. (2007). Care of the suicidal person. London: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- De Leo D., Dello Buono M., & Dwyer J. (2002). Suicide among the elderly: The long-term impact of a telephone support and assessment intervention in northern Italy. British Journal of Psychiatry, 181, 226–229. doi 10.1192/bjp.181.3.226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health. (2002). National suicide prevention strategy for England. London, UK: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Eagles J. M., Carson D. P., Begg A., & Naji S. A. (2003). Suicide prevention: A study of patients’ views. Journal of Psychiatry, 182, 261–265. doi 10.1192/bjp.02.300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldrid J. (1988). Caring for the suicidal. London: Constable. [Google Scholar]

- Evans M., Morgan G., & Hayward A. (2002). Crisis telephone consultation for deliberate self-harm patients: How the study groups used the telephone and usual health care services. Journal of Mental Health, 9, 155–164. doi 10.1080/09638230050009159 [Google Scholar]

- Fairbairn G. J. (1995). Contemplating suicide: The language and ethics of self-harm. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Fakhoury W. K. H. (2002). Suicidal callers to a national helpline in the UK: A comparison of depressive and psychotic sufferers. Archives of Suicide Research, 6, 363–371. doi 10.1080/13811110214532 [Google Scholar]

- Fleischmann A., Bertolote J. M., Wasserman D., De Leo D., Bolhari J., Botega N. J., ... Thanhk H. T. T. (2008). Effectiveness of brief intervention and contact for suicide attempters: A randomized controlled trial in five countries. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 86, 657–736. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/86/07-046995.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flick U. (2009). An introduction to qualitative research. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Fukkink R. G., & Hermanns J. (2009). Children’s experiences with chat support and telephone support. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 50, 759–766. doi 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.02024.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnell D., & Frankel S. (1994). Prevention of suicide: Aspirations and evidence. British Medical Journal, 308, 1227–1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo B., & Harstall C. (2004). For which strategies of suicide prevention is there evidence of effectiveness? (WHO Regional Office for Europe’s Health Evidence Network report). Copenhagen, Denmark: WHO. [Google Scholar]

- Guo B., Scott A., & Bowker S. (2003). Suicide prevention strategies: Evidence from systematic reviews (HTA 28). Alberta, Canada: Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research. Retrieved from http://www.ihc.ca/documents/suicide_prevention_strategies_evidence.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Hall B., & Schlosar H. (1995). Repeat callers and the Samaritan telephone crisis line – A Canadian experience. Crisis, 16, 66–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison H. (2000). Childline – The first twelve years. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 82, 283–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgitt A. (2000). Suicide reduction: Policy context. International Review of Psychiatry, 12, 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Holding T. A. (1974). The B. B. C. befrienders’ series and its effects. British Journal of Psychiatry, 124, 470–472. doi 10.1192/bjp.124.5.470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jianlin J. (1995). Hotline for mental health in Shanghai, China. Crisis, 16, 116–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalafat J., Gould M. S., Munfakh J. L., & Kleinman M. (2007). An evaluation of crisis hotline outcomes. Part 1: Nonsuicidal crisis callers. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 37, 322–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King R., Nurcombe B., Bickman L., Hides L., & Reid W. (2003). Telephone counseling for adolescent suicide prevention: Changes in suicidality and mental state from beginning to end of a counseling session. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 33, 400–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leenaars A. A., & Lester D. (2004). The impact of suicide prevention centers on the suicide rate in the Canadian provinces. Crisis, 25, 65–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitner M., Barr W., & Hobby L. (2008). Effectiveness of interventions to prevent suicide and suicidal behavior: A systematic review. Edinburgh, UK: Scottish Government Social Research. Retrieved from http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Resource/Doc/209331/0055420.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Lipczynska S. (2009). Web review: Suicide. Journal of Mental Health, 18, 188–191. [Google Scholar]

- Mann J. J., Apter A., Bertolote J., Beautrais A., Currier D., Haas A., ... Hendin H. (2005). Suicide prevention strategies: A systematic review. Journal of the American Medical Association, 294, 2064–2074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maris R. W. (2002). Suicide. The Lancet, 360, 319–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mead N., Lester H., Chew-Graham C., Gask L., & Bower P. (2010). Effects of befriending on depressive symptoms and distress: Systematic review and meta-analysis. British Medical Journal, 196, 96–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mental Health Helplines Partnership. (2003). Help on the Line. What commissioners and funders need to know about mental health helplines. London, UK: Telephones Helpline Association. [Google Scholar]

- Miller H. L., Coombs D. W., Leeper J. D., & Barton S. N. (1984). An analysis of the effects of suicide prevention facilities on suicide rates in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 74, 340–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishara B. L. (1997). Effects of different telephone intervention styles with suicidal callers at two suicide prevention centers: An empirical investigation. American Journal of Community Psychology, 25, 861–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishara B. L., Chagnon F., Daigle M., Balan B., Raymond S., Marcoux I., ... Berman A. (2007). Which helper behaviors and intervention styles are related to better short-term outcomes in telephone crisis intervention? Results from a silent monitoring study of calls to the U. S. 1-800-SUICIDE Network. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 37, 308–321. doi 10.1521/suli.2007.37.3.308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murthy D. (2008). Digital ethnography: An examination of the use of new technologies for social research. Sociology, 42, 837–855. [Google Scholar]

- Nock M. K., Borges G., Bromet E. J., Cha C. B., Kessler R. C., & Lee S. (2008). Suicide and suicidal behavior. Epidemiologic Reviews, 30, 133–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollock K., Armstrong S., Coveney C. M., & Moore J. (2010). An evaluation of Samaritans e-mail and telephone emotional support service. Nottingham, UK: University of Nottingham. [Google Scholar]

- Potenza M. N., Steinberg M. A., McLaughlin S. D., Wu R., Rounsaville B. J., & O’Malley S. S. (2001). Gender-related differences in the characteristics of problem gamblers using a gambling helpline. American Journal of Psychiatry, 158, 1500–1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prout M. N., Martinez O., Ballas J., Geller A., Lash T., Brooks D., & Heeren T. (2002). Who uses the Smoker’s Quitline in Massachusetts? Tobacco Control, 11(Suppl. 2), 74–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samaritans. (2003). Emotional health promotion strategy: Changing our world. Ewell, UK: Author. Retrieved from http://www.samaritans.org/pdf/EmotionalHealthPromotionStrateg2003.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Samaritans. (2004). Hearing the caller’s voice. Ewell, UK: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Samaritans. (2011). Information resource pack 2011. Ewell, UK: Author. Retrieved from http://www.samaritans.org/pdf/Samaritans%20Info%20Resource%20Pack%202011.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Shekelle P., & Roland M. (1999). Nurse-led telephone advice lines. The Lancet, 354(9173), 88–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson D., & Thompson J. (1974). Nightline – A student self-help organization. British Journal of Guidance and Counseling, 2, 200–211. [Google Scholar]

- Varah C. (Ed.). (1988). The Samaritans: Befriending the suicidal. London, UK: Constable. [Google Scholar]

- Wakeling D. (1999). Unlimited menu? The crisis care continuum and the nonvoluntary sector. Journal of Mental Health, 8, 547–550. [Google Scholar]