Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are the most common mesenchymal tumor of the gastrointestinal tract. Soon after GIST was recognized as a tumor driven by a KIT or PDGFRA mutation, it became the first solid tumor target for tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapies. More recently, alternative molecular mechanisms for GIST pathogenesis have been discovered. These are related to deficiences in the succinate dehydrogenase complex, NF1-gene alterations in connection with neurofibromatosis 1 tumor syndrome, and mutational activation of the BRAF oncogene in very rare cases.

Clinically GISTs are diverse. They can involve almost any segment of the gastrointestinal tract from distal esophagus to anus although the stomach is the most common site. From an oncologic perspective, GIST varies from a small, harmless tumor nodule to a metastasizing and life-threatening sarcoma. This review presents the clinical, pathological, prognostic, and to some degree, oncological aspects of GISTs with attention to their clinicopathologic variants related to tumor site and pathogenesis.

HISTORY OF GIST AND TERMINOLOGY

What is now known as GIST, used to be called gastrointestinal (GI) smooth muscle tumor: leiomyoma if benign, leiomyosarcoma if malignant, and leiomyoblastoma if with epithelioid histology. Tumors previously classified as gastrointestinal autonomic nerve tumors have also turned out to be GISTs, as have many tumors historically classified as gastrointestinal schwannomas or other nerve sheath tumors.

Electron microscopic studies from the late 1960’s and on demonstrated that most of the “GI smooth muscle tumors” differed from typical smooth muscle tumors by their lack of smooth muscle-specific ultrastructure. 1 Immunohistochemically they lacked smooth muscle antigens, especially desmin. 2 As they also lacked Schwann cell features, gastrointestinal stromal tumor was then proposed as a histogenetically non-committal term for these tumors. 3 The discovery of KIT expression and gain-of-function KIT mutations in GIST in 1998 was the basis of the modern concept of GIST – a generally KIT positive and KIT mutation-driven mesenchymal neoplasm specific to the gastrointestinal tract. 4,5

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF GIST

GIST, once considered and obscure tumor, is now known to occur with an incidence of at least 14–20 per million, by population-based studies from northern Europe. 6,7 These estimates represent the minimum incidence, as subclinical GISTs are much more common. In an US study, 10% of well-studied resection specimens of gastroesophageal cancer harbored a small incidental GIST in the proximal stomach. 8 An autopsy study from Germany also found a 25% incidence of small gastric GISTs. 9

GISTs typically occur in older adults, and the median patient age in the major series has varied between 60–65 years. GISTs are relatively rare under the age 40 of years, and only <1% occur below age 21. Some series have shown a mild male predominance. Over half of the GISTs occur in the stomach. Approximately 30% of GISTs are detected in the jejunum or ileum, 5% in the duodenum, 5% in the rectum, and <1% in the esophagus. Based on our review of Armed Forces Institute of Pathology (AFIP) cases, as many as 10% of all GISTs are detected as advanced, disseminated abdominal tumors whose exact origin is difficult to determine.

Despite occasional reports to the contrary, we do not believe that GISTs primarily occur in parenchymal organs outside the GI tract at sites such as the pancreas, liver, and gallbladder. At the two first mentioned organs, GISTs are metastatic or direct extensions from gastric or duodenal, or other intestinal primary tumors. We are skeptical about primary GISTs in the gallbladder and note that the reported evidence for this diagnosis is tenuous and that molecular genetic documentation is absent. 10,11 Furthermore, review of all gallbladder sarcomas in the AFIP failed to find any GISTs. 12 Similarly, GISTs diagnosed in prostate biopsies are of rectal or other gastrointestinal and not prostatic origin. 13

GIST IS PHENOTYPICALLY RELATED TO GASTROINTESTINAL CAJAL CELLS

Almost all GISTs express the KIT receptor tyrosine kinase, similar to the gastrointestinal Cajal cells that regulate the GI autonomic nerve system and peristalsis. 14 These cells have a stem cell-like character, as demonstrated by their ability to transdifferentiate into smooth muscle. 15 KIT-deficient mice lack gastrointestinal Cajal cells and those with introduced KIT-activating mutations develop Cajal cell hyperplasia and GISTs, supporting the role of Cajal cells in GIST oncogenesis. 16

KIT AND PDGFRA MUTATION AS A DRIVING FORCE OF GISTs

Most GISTs, approximately 85–90%, contain oncogenic KIT or platelet derived growth factor receptor (PDGFRA) mutations. KIT and PDGFRA are two highly homologous cell surface tyrosine kinase receptors for stem cell factor and platelet-derived growth factor alpha respectively. Normally these kinases are activated (phosphorylated) upon dimerization induced by ligand binding. However, mutated receptors may self-phosphorylate in a ligand-independent manner, rendering the kinase consitutively activated. This has a critical role in cell proliferation and is considered the driving force of GIST pathogenesis. However, additional genetic changes are necessary for malignant progression as mutations are already detectable in the very small GISTs, most of which probably never grow to clinical tumors 17–20

How KIT mutations cause increased cell proliferation has been demonstrated in several ways. KIT mutations introduced in a lymphoblastoid cell line increased cellular proliferation. Families with germline KIT or PDGFRA mutation and transgenic mouse with similar “knock-in” KIT mutations have predisposition to GIST, often developing multiple GISTs. 4 Also, it has been shown that KIT mutations are associated with constitutively phosphorylated KIT 21 and that KIT tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as imatinib mesylate can in vitro and in vivo abolish the phosporylated status and normalize the increased cell proliferation. 21

The clinical significance of mutation type analysis includes assessment of sensitivity to tyrosine kinase inhibitors (especially imatibib), and in some cases, mutation type, can also offer a prognostic clue. 22 The rare presence of homozygous mutation is associated with an aggressive course of disease. The main KIT mutation types and their clinical significance is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of the main KIT and PDGFRA mutation types and their clinical significance.

| Gene | Domai n |

Exo n |

Type of Mutation | Frequency | Clinicopathologic features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KIT | EC | 9 | Duplication | 10% | Associated with intestinal tumors |

| JM | 11 | Deletion | 70% | Deletions and deletion/insertions associated with malignant course especially in gastric tumors |

|

| Deletion/insertion | |||||

| Duplication | Duplication associated with gastric tumors and favorable course |

||||

| Insertion | |||||

| Substitution | |||||

| TK1 | 13 | Substitution | 1% | Slightly more frequent in intestinal tumors | |

| Associated with spindle cell morphology | |||||

| TK2 | 17 | Substitution | 1% | More frequent in intestinal tumors | |

| Associated with spindle cell morphology | |||||

| PDGF RA |

JM | 12 | Deletion | 1% | Associated with gastric tumors, epithelioid cell morphology and more indolent course |

| Deletion/insertion | |||||

| Duplication | |||||

| Substitution | |||||

| TK1 | 14 | Substitution | <1% | ||

| TK2 | 18 | Deletion | 5% | ||

| Deletion/insertion | |||||

| Duplication | |||||

| Substitution | |||||

KIT EXON 11 MUTANTS

Approximately 90% of KIT mutations involve exon 11, the juxtamembrane domain. 18,20 Their KIT activating potential is believed to be related to disruption of the alpha-helical structure of the juxtamembrane domain then allowing spontaneous dimerization and phoshorylation of KIT. 23 Exon 11 KIT mutations include a spectrum of in-frame deletions of 3–21 or rarely more base pairs, single nucleotide substitutions, internal tandem duplications, and combinations of the above, and rarely true insertions of non-duplicative genomic sequences. 17–20 In general, most KIT exon 11 mutants are sensitive to the tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib mesylate.

Deletions in the KIT juxtamemembrane domain most frequently involve the 5’ portion of the exon 11 between codons 550–560. Tumors containing deletions in this area are clinically more aggressive than those with single nucleotide substitutions. 24,25 In large site-specific series, this was especially true for gastric GISTs. 26

KIT exon 11 single nucleotide substitutions are generally limited to 4 codons: 557, 559, 560, and 576. Internal tandem duplications are essentially restricted to the 3’ portion of exon 11 and are associated with gastric tumors and favorable course. 27 In general, most KIT exon 11 mutants are sensitive to the tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib mesylate, although some rare variants may show different level of resistance. 18

OTHER KIT MUTANTS

KIT extracellular domain exon 9 mutations are rare and essentially restricted to intestinal GISTs based on Western studies. 28,29 However, in a Japanese series these mutations have also been detected in some gastric GISTs, raising the possibility of population differences. 30 Most mutations are identical 2 codon duplications introducing a tandem alanine-tyrosine pair (AY502–503). These KIT Exon 9 mutant GISTs are notable for their poorer response to imatinib, so that dose escalation of imatinib from 400 mg/day to 800 mg per day or use of alternative tyrosine kinase inhibitor has been advocated. 31,32 However, in a large pre-imatinib series, KIT exon 9 mutant GISTs did not seem to have an inherently worse prognosis than exon 11 mutant tumors.33

Rarely, KIT tyrosine kinase 1 domain (exon 13) or tyrosine kinase 2 domain (exon 17) is mutated. Exon 13 mutations usually involve codon 642 while exon 17 mutations most often occur in codon 822.34,35 These mutants are variably sensitive to imatinib.

PDGRFA MUTATIONS IN GISTs

PDGFRA mutations were discovered in 30% of KIT wild type (WT) tumors. KIT and PDGFRA mutations were shown to be mutually exclusive in GISTs. 36 PDGFRA mutants are essentially restricted to gastric GISTs, comprising approximately 10% of such cases overall. Most PDGFRA-mutant gastric GISTs represent clinically indolent tumors. Also, there is some predilection to epithelioid morphology, and some of these tumors show weaker KIT-expression. 37 Although they express PDGFRA, standard immunohistochemistry is not helpful for the detection of PDGFRA-mutant GISTs as PDGFRA is widely expressed in GISTs of any type and also in other tumors. PDGFRA mutations, similar to KIT mutations, include in-frame deletions, single nucleotide substitutions and internal tandem duplications. A large majority of these mutations are D842V substitutions involving the PDGFRA tyrosine kinase 2 domain (exon 18), although rare mutations have been identified in juxtamembrane domain (exon 12) and tyrosine kinase 1 domain (exon 14). 37 D842V mutants are notorious for their primary resistance to imatinib. Therefore for initial therapy, if oncologically indicated, an alternative, more potent, tyrosine kinase inhibitors should be selected. 38

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS OF GIST

Most common clinical symptoms of GIST are GI bleeding and gastric discomfort or ulcer-like symptoms. The bleeding varies from chronic insidious bleeding often leading to anemia to acute life threatening episodes of melena or hematemesis. Few GISTs manifest as other abdominal emergencies, such as intestinal obstruction or tumor rupture with hemoperitoneum. Nearly a third of GISTs are incidentally detected during surgical or imaging procedures or endoscopic screening for gastric carcinoma. Some rectal GISTs are detected during prostate or gynecologic examination.

The majority of currently detected GISTs are localized tumors < 5 cm, but retrospective studies had larger mean tumor sizes. In general, small intestinal GISTs are larger in average and the percentage of metastasizing tumors is higher than among gastric GISTs. Peritoneal cavity and liver are the typical sites of metastases. Rarely, GISTs metastasize into bones. In our experience, bone metastases have a predilection to axial skeleton, especially the spine. Cutaneous and peripheral soft tissue metastases are rare. In contrast to other sarcomas, malignant GISTs very rarely if ever metastasize to lungs, even if they have extensive other metastases. While some GISTs metastasize in 1–2 years or sooner, metastatic spread is possible after a very long delay. 26,33 The longest interval from primary tumor to liver metastasis observed by us was 42 years. This indicates the need for long-term patient follow-up.

IDENTIFICATION OF GISTs

Radiologists, endoscopists, and surgeons and pathologists can suspect a GIST whenever there is a rounded to oval, circumscribed mural or extramural non mucosa-based mass of any size that involves or is closely associated with the stomach, intestinal segments, or lower esophagus. However, in some cases such lesions prove to be other mesenchymal tumors, unusual variants of carcinomas, neuroendocrine tumors, or even lymphomas. In most cases, examination of a biopsy easily resolves the differential diagnostic problem. A GIST should also be considered for any palpable abdominal mass.

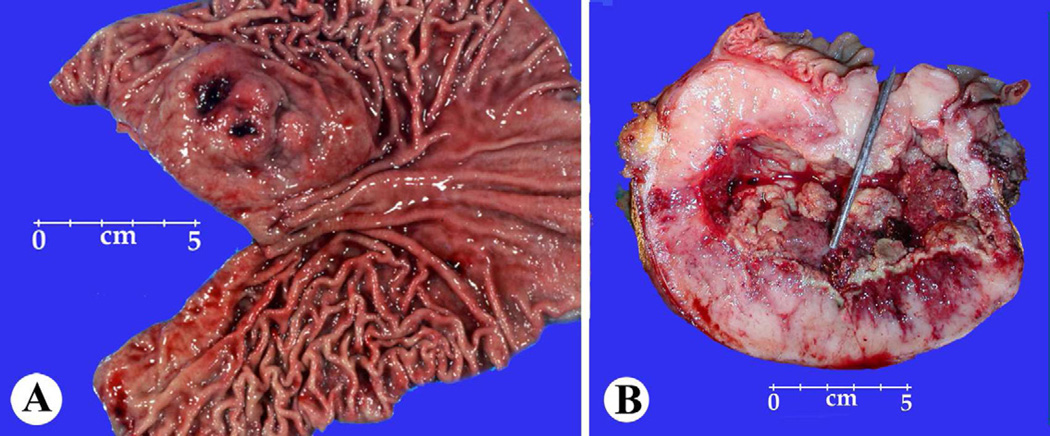

The radiologic and gross appearances of GISTs, especially the gastric ones, can be highly variable including tumors with intraluminal, intramural, external components and with pedunculated extramural and cystic appearances. Any larger GIST in the intestines typically forms an externally extending mass that is often centrally cystic and may fistulate into the lumen (Fig 1). Some small intestinal GISTs form dumbbell-shaped masses with intramural and external components. 26,39

Fig. 1.

A,B, Gross features of a gastric GIST showing multinodular submucosal masses and a small intestinal GIST showing a fistula tract connecting the center of the tumor to the intestinal lumen.

GIST is the most common mesenchymal tumor in all segments of the GI tract with two exceptions: most esophageal mesenchymal tumors are true leiomyomas and not GISTs, and small mucosal leiomyomas are more common in the colon and rectum than are GISTs. In the stomach, GIST is by far the most common mesenchymal tumor, as there are only 4 leiomyomas or schwannomas reported for every 100 GISTs.

Sampling of a GIST for preoperative diagnosis via endoscopic mucosal biopsy is successful in only 20–30% cases, including those that involve the mucosa or superficial submucosa. Endoscopic ultrasound-associated fine needle aspiration biopsy (EUS-FNA) is more promising. 40 In a recent study, the diagnostic yield of EUS-FNA was 76% , while even better results were reported with Tru-cut histologic biopsies (97% yield of diagnostic material). 41 The larger GISTs especially are amenable to CT-guided needle core biopsy.

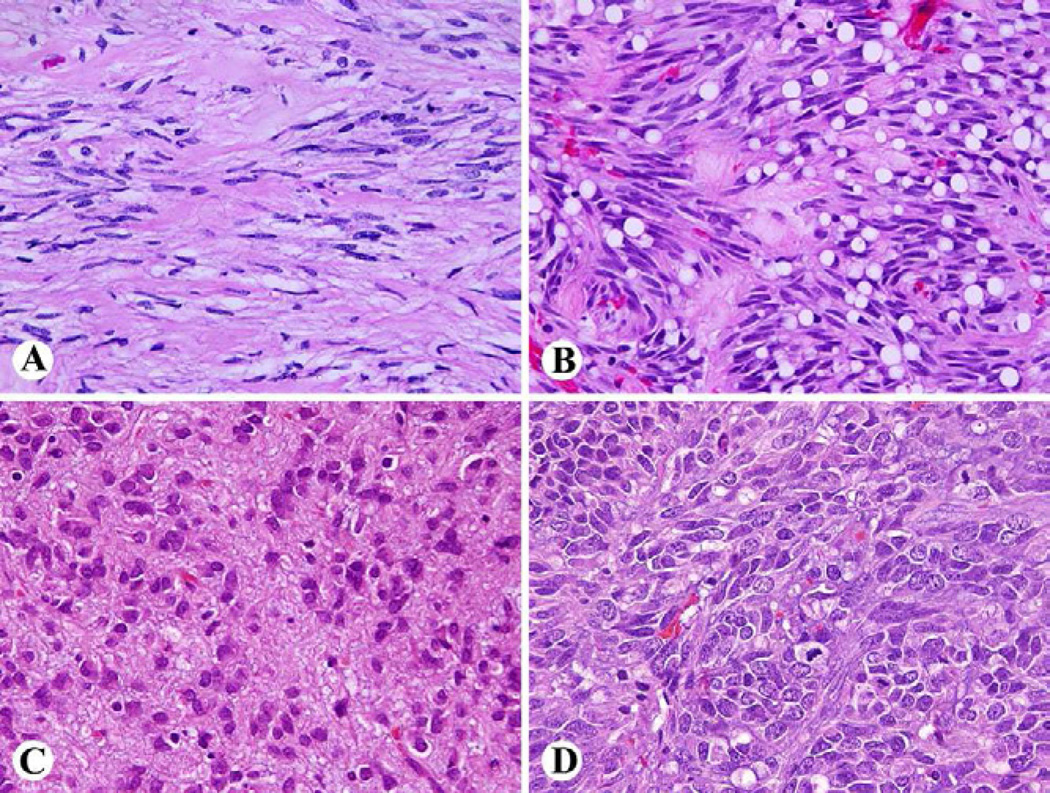

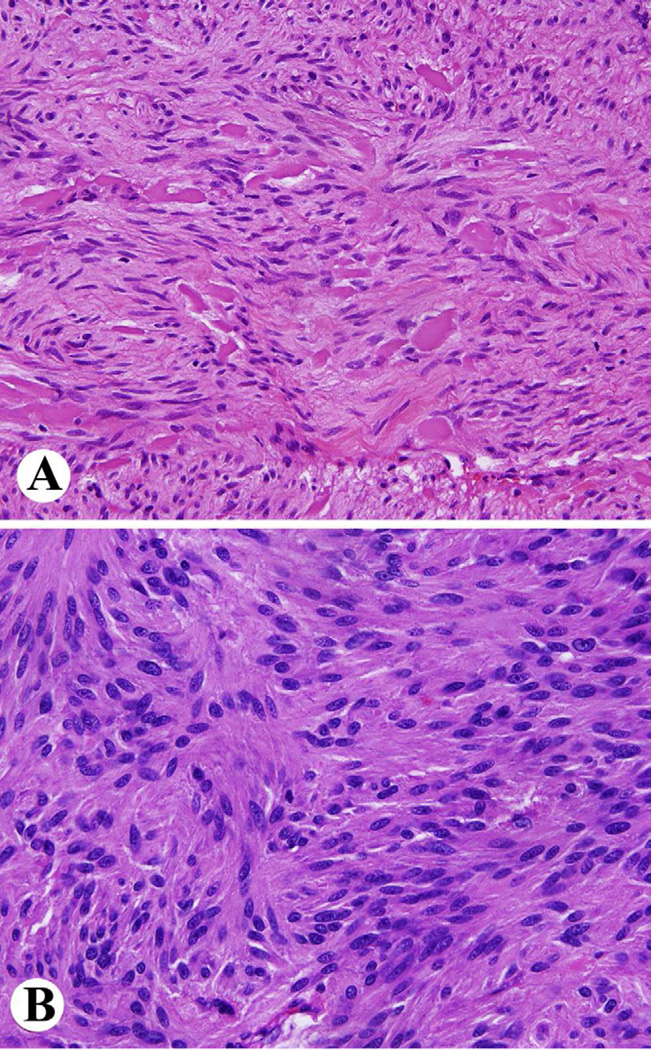

Pathologic diagnosis of GIST is based on identification of a mesenchymal neoplasm with spindle cell or epithelioid histology that is generally positive for KIT (CD117 leukocyte antigen). Common histologic features in GISTs include spindle cells with sclerosing matrix, perinuclear vacuolization and nuclear palisading, epithelioid cytology, and sarcomatoid, mitotically active morphology in gastric GISTs (Fig. 2). Small intestinal GISTs are characterized by extracellular collagen globules and a Verocay body or neuropil-like material, reflecting complex entangled cell processes (Fig. 3).

Fig 2.

Wide spectrum of histologic features of gastric GIST. A. Paucicellular tumor with sclerosing matrix. B. Perinuclear vacuolization and nuclear palisading. C. Epithelioid cytology. D. Sarcomatoid appearance with numerous mitoses.

Fig. 3.

Histology of small intestinal GIST. A. Spindle cell tumor with extracellular collagen globules. B. Anuclear zones reflecting prominent entangled cell processes.

Approximately 97% of GISTs are immunohistochemically positive for KIT, at least focally, but the pattern can vary from membranous and apparent cytoplasmic to a perinuclear dot-like pattern. 42,43 Tumors with epithelioid cytology can be only focally positive, or rarely entirely negative, which can be the cases especially with some PDGFRA-mutant GISTs. 44,45 The KIT-negative GISTs are usually positive for anoctamin-1, (Ano-1) a calcium activated chloride channel protein also expressed in Cajal cells. 46 Ano-1 is also known under the aliases DOG1 (discovered on GIST-1), and ORAOV2 (overexpressed in oral carcinoma). 47 Approximately 97% of GISTs are Ano-1 positive including KIT-negative GISTs, but some GISTs, especially small intestinal ones, are negative. Together KIT and Ano-1 capture nearly 100% of GISTs as their “shadow areas” tend to be different. 48 Other potential but less specific and sensitive markers in the overall detection of GISTs are protein kinase C theta 49,50 and CD34. The latter is positive in 70% of GISTs and is nearly consistently detected in gastric spindle cell GISTs. 26

For comprehensive detection of GISTs, one should consider that most gastrointestinal mesenchymal tumors are GISTs, and that a great majority of intraperitoneal mesenchymal tumors are also GISTs. Even in the retroperitoneal space, a GIST is more common than a leiomyosarcoma, in our experience. GIST should also be considered in the differential diagnosis of mesenchymal or epitheloid neoplasms involving the liver, pancreas, and pelvic cavity.

GIST PROGNOSIS AT DIFFERENT SITES

The best universally applicable prognostic parameters are tumor size (maximum tumor diameter in cm) and mitotic rate per 50 high power fields (corresponding to 5 mm2). A prognostic chart (Table 2) has been devised by analysis of large series of gastric and small intestinal GISTs, based on AFIP cases with long-term follow-up. 26,33,51 This chart shows that gastric and small intestinal GISTs ≤ 5 cm with mitotic count ≤ 5/50 HPFs have a very good prognosis with only 3–5% of metastatic risk. Also, the chart shows a marked prognostic difference between gastric and small intestinal GISTs. The latter show significant to high metastatic rates in many categories that in the gastric location have much lower rate of metastases. Other intestinal GISTs have a prognosis approximately similar to small intestinal GISTs, although less data exists, due to their rarity. Prognostic nomograms creating the above parameters as continuous variables have also been devised. Based on a relatively small sample size, such a nomogram was found to offer a more accurate prognostication. 52 Addition of genetic parameters may further improve prognostication. The number and type of genomic losses and gains detected by comparative genomic hybridization 53 and genome complexity index are examples of this development. In the latter, expression of aurora kinase was found an adverse prognostic factor. 54

Table 2.

Prognostication of GIST of different sites by tumor size and mitotic rate based on follow-up studies of over >1700 GISTs prior to imatinib.

| Tumor parameters | Percentage of patients with progressive disease during long-term follow-up and quantitative characterization of the risk for metastasis |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Size | Mitotic Rate |

Gastric GISTs |

Small intestinal GISTs |

Duodenal GISTs |

Rectal GISTs |

| 1 | ≤ 2 cm | ≤ 5/50 HPFs |

0 none | |||

| 2 | > 2 ≤ 5 cm | 1.9 (very low) | 4.3 (low) | 8.3 (low) | 8.5 (low) | |

| 3a | > 5 ≤ 10 cm | 3.6 (low) | 24 (moderate) | 34 (high)* | 57 (high)* | |

| 3b | > 10 cm | 12 (moderate) | 52 (high) | |||

| 4 | ≤ 2 cm | > 5/50 HPFs |

0* | 50* | ** | 54 (high) |

| 5 | > 2 ≤ 5 cm | 16 (moderate) | 73 (high) | 50 (high) | 52 (high) | |

| 6a | > 5 ≤ 10 cm | 55 (high) | 85 (high) | 86 (high)* | 71 (high)* | |

| 6b | > 10 cm | 86 (high) | 90 (high) | |||

Small number of cases. Groups combined or prognostic prediction less certain.

No tumors encountered with these parameters. Table adopted from Miettinen et al. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2006;130:1466–1478. HPF = high power field. 50 high power fields equal here approximately 5 mm2.

COMMENTS ON GIST SURGERY

Wedge resection is the most common surgery for a small to medium-sized gastric GIST and sufficient margins can usually be obtained. Results vary about the significance of microscopically negative margins after gross resection. While in one study a microscopically positive margin was not found to be a significant adverse factor 55 , another study found it an adverse factor for survival. 56 Localized intestinal GISTs are handled with segmental resections. Laparosopic surgery is increasingly used for small or medium- sized GISTs (at least up to 5 cm). Reported series have shown excellent survival results (92–96%) 57,58 , which also reflect the fact that most gastric GISTs < 5 cm are clinically favorable. 26 One study also found that laparoscopic vs. open surgery offered similar 30-day morbidity and outcome but shorter hospital stay (4 vs. 7 days) and slightly less blood loss with the laparoscopic group. Conversion into open surgery was often the result of a tumor location in the gastroesophageal junction or lesser curvature. 59 Larger GISTs necessitate open surgery and more extensive resections, such as distal gasterctomies for tumors involving the pyloric region or lesser curvature regions. 60,61 Total gastrectomy may be needed for very large or multiple and recurrent GISTs that include the SDH-deficient GISTs in young patients. This subgroup is discussed in detail below. Tumor manipulation and rupture should be avoided, as this increases the possibility of peritoneal seeding.

Surgery of metastases following imatinib treatment is practiced in selected instances. The indications include excision of metastases with developing imatinib resistance and emergency surgery for ruptured cystic metastases. 62 In CT scans, peripheral thickening and enhancing of cystic metastases can be a sign of a evolving resistance and newly progressing tumor even without size increase. 63

COMMENTS ON ONCOLOGIC TREATMENT OF GISTs

The KIT tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib mesylate, initially introduced for treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia due to its ability to inhibit ABL tyrosine kinase, was also found to inhibit KIT and to be effective in a patient with extensive hepatic and abdominal metastases. 64 Today imatinib is the treatment of choice for metastatic and unresectable GIST, and it offers prolonged survival for an average of 5 years, compared with historical controls. Orally administered imatinib is safe with few side effects. Unfortunately, tumors often develop resistance, mostly due to secondary KIT or rarely PDGFRA mutations that cluster in the tyrosine kinase domains. 65–67

More recently imatinib has also been used as adjuvant therapy after apparently complete surgery in order to prevent recurrences, with several clinical trials supporting its use in this context. In general, imatinib is recommend after completely resective surgery of high-risk GISTs 65–67, although some trials have used it with wider indications, such as GISTs > 3 cm. 68 In a recent randomized trial treatment for 3 years showed a survival advantage over one year treatment. 69

In addition, imatinib has been used as a neo-adjuvant treatment prior to surgery. In some cases, adjuvant treatment for imatinib can shrink the tumor to allow more structure-preserving surgery, and this may especially important for GISTs at technically challenging sites such as the anorectum. 65–67

Several newer tyrosine kinase inhibitors, such as sunitinib, nilotinib, and dasatinib, are being used to overcome imatinib resistance. These multi-kinase inhibitors inhibit other tyrosine kinases, such as vascular endothelial growth factor receptors, in addition to KIT and PDGFRA. Although variably effective against imatinib-resistant GISTs these new inhibitors have a greater spectrum of side effects. 70 Additional new potential drugs currently under evaluation in in-vitro models or being used in early trials include MTOR inhibitors such as everolimus71, heat shock protein inhibitors 72, and the KIT transcription antagonist flavopiridol. 73

FAMILIAL GIST SYNDROME

Hereditary GIST syndrome is a rare autosomal dominant disorder characterized by germline gain-of-function KIT mutations and in rare cases by PDGFRA mutations. Structurally, these mutations are similar to those reported in sporadic tumors, although in one kindred KIT exon 8 was mutated. More than twenty families with hereditary GIST syndrome have been reported. Affected individuals develop Cajal cell hyperplasia and subsequently multiple GISTs in middle age. Dysphagia, skin hyperpigmentation, urticarial pigmentosa and mastocytosis are among other clinical features occasionally seen in the kindreds harboring KIT but not PDGFRA germline mutations. The tumors may remain stable for a long time, but often ultimately become aggressive. 16,18,75

SUCCINATE DEHYDROGENASE (SDH) DEFICIENT GISTs

Approximately 7.5% of gastric GISTs, especially those in children and young adults, have tumor-specific loss of function of the succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) complex, which is considered a key factor in their pathogenesis. The SDH complex is an important metabolic enzyme complex participating both in the tricarboxylic acid cycle and in the electron transfer chain located in the mitochondrial inner membrane. SDH-deficient GISTs are restricted to the stomach, based on screening of large numbers of GIST of different locations. These tumors lack KIT and PDGFRA mutations and are not driven by activation of these oncogenes. 75–78

The pathogenesis of SDH-deficient GISTs is related to germline loss-of-function mutations in the SDH subunit proteins, as found in 20–30% of extra-adrenal paragangliomas. In GIST patients, SDHA is the most commonly mutated subunit, but subunits B, C, and D can also be involved. 75–79 At least half of the patients have germline mutations, to which are added corresponding somatic mutations in the tumors, thereby leading to inactivation of the subunit and subsequently loss of function of the entire SDH-complex in the tumor. However, for patients who lack SDH-germline mutations, while the underlying genetic defects are unknown the biologic pathways affected are believed to be activated hypoxia-inducible factor signaling. Activation of the insulin-like growth factor 1-receptor (IGF1R) signaling seems to be a oncogenic signaling consequence of these changes. 75

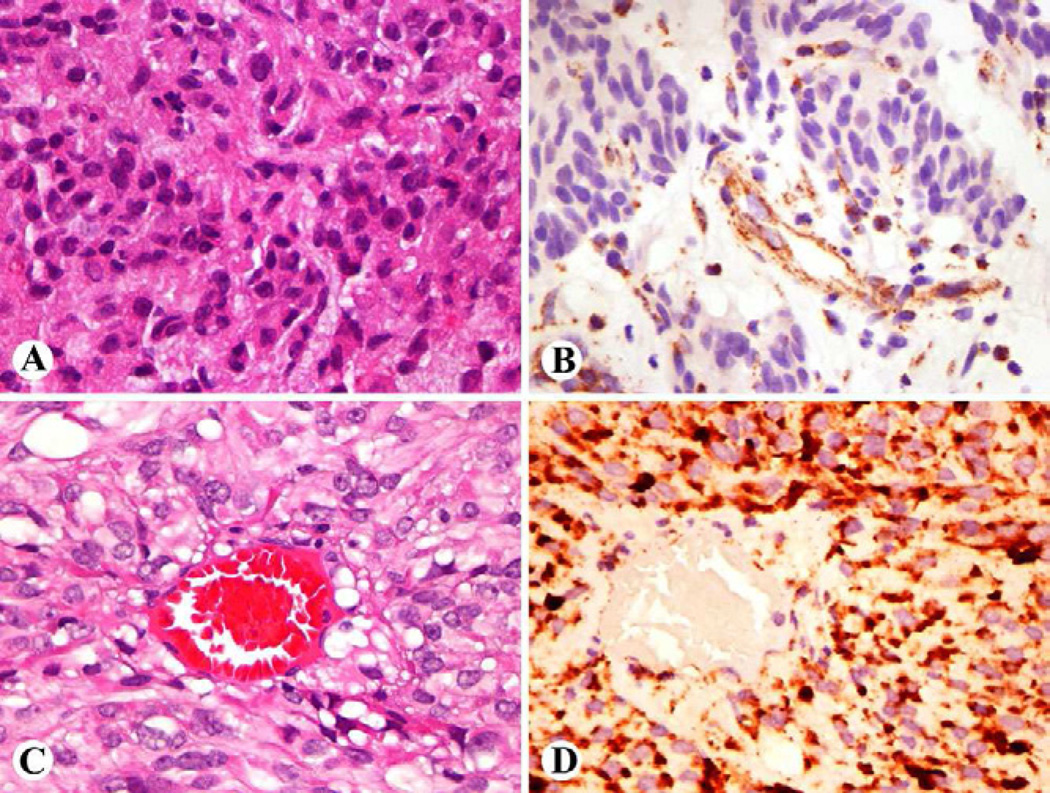

The practical diagnostic marker for SDH-deficient GISTs is immunohistochemically observed loss of the otherwise ubiquitously expressed SDHB (Fig 4). 78,80,81 This loss occurs with the loss of any of the subunits, as has been seen in paragangliomas. SDHA-mutant tumors specifically show immunohistochemical loss of SDHA, which can also be detected immunohistochemically. 79,82–84 Currently, no reliable immunohistochemical tests are available for analysis of SDHC and SDHD subunits.

Fig 4.

A, B. Succinate dehydrogenase deficient GIST shows epithelioid cell morphology and shows loss of SDHB, which is only present in non-neoplastic vascular and stromal components. C,D. A conventional GIST in comparison shows granular cytoplasmic staining for SDHB.

SDH-deficient GISTs have a predilection to children and young adults, and constitute a great majority of pediatric GISTs and half of all gastric GISTs under the age of 40 years. They may occur in older adults but with a lower frequency. The children involved are usually girls, and onset is mostly in the second decade. In rare patients the GIST is diagnosed before the age of 10 years. Curiously, no significant familial tendency (multiple affected family members) have been observed for SDH-deficient GISTs, even though up to 50% of patients have germline mutations. 78

Two clinical syndromes distinguished by eponyms are included among the SDH-deficient gastric GISTs. The occurrence of GIST with a paraganglioma in a patient with a SDH-subunit germline mutation defines Carney-Stratakis syndrome. 85 Occurrence of a GIST and a paraganglioma or a pulmonary chondroma or all three in the absence of an SDH-gene germline mutation defines the Carney triad. 86 In our experience, these syndromes together comprise only a minority of SDH-deficient GISTs (10–20%), although this percentage could become higher with extended follow-up and radiologic screening for occult paragangliomas.

Clinically, the SDH-deficient GISTs are distinctive in that they often form multiple gastric tumors. There is some tendency to form regional perigastric lymph node metastases and multiple peritoneal micronodules, but neither of these seems to be a prognostically adverse event. Many patients develop gastric recurrences and ultimately undergo total gastectomy over years. Liver metastases develop in 20–25%, but nevertheless, the patients often survive for a long time even with these metastases – an outcome different from KIT-mutant GISTs. Tumor-related mortality was approximately 15% in a cohort with 15-year median follow-up. 78,79 In general, SDH-deficient GISTs are less predictable than KIT-mutant GISTs with the same prognostic factors. Life-long follow-up is needed as the patients continue to be at risk of development of liver metastases and other syndrome-related tumors, such as paragangliomas. The longest interval from primary tumor to liver metastasis in our study was 42 years. Similar clinicopathologic features have also been observed in Carney triad GISTs, a subgroup of SDH-deficient GISTs. 86

Pathologically, SDH-deficient GISTs are notable for characteristic morphology: they have epithelioid cytology and multinodular gastric intramural involvement and a tendency for lymphovascular invasion and lymph node metastases. Notably, neither of the latter features are adverse prognostic factors. 78,79,86

Optimal treatment for SDH-deficient GISTs remains to be determined. However, these tumors do not show a similar imatinib response as generally observed with KIT-mutant GISTs. Alternative tyrosine kinase inhibitors, such as sunitinib malate, have been used, but the data is relatively scant. Inhibition of insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor is a possible new treatment strategy for the SDH-deficient GISTs. 87,88

GISTs IN NEUROFIBROMATOSIS 1 PATIENTS

According to our estimate based on AFIP files, approximately 1–2% of GISTs arise in patients with neurofibromatosis 1, so that GISTs belongs to the spectrum of tumors that occur in connection with this tumor syndrome, in addition to the constellation of neurofibromas, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors, pheochromocytomas, and others in NF1.

An autopsy study on NF1 patients found a third of NF1 patients to harbor undiagnosed GISTs, so that the frequency of GISTs in NF1 patients is probably high. 89 Furthermore, in our review of AFIP files, we could not identify a single malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor in the gastrointestinal tract, and found that an overwhelming majority of GI mesenchymal tumors in NF1 patients are actually GISTs.

The GISTs occurring in connection with NF1 are typically located in the small intestine (or sometimes colon), and gastric GISTs in these patients are rare. These GISTs are often multiple, and a majority of them are incidental findings during other abdominal surgeries. However, approximately 15–20% of NF1-associated GISTs are clinically malignant. 89–91

BRAF MUTANT GISTs

Recently, an identical BRAF mutation (V600E) was identified in a small subset of KIT-and PDGFRA-WT GISTs. Oncogenic BRAF activation is considered to be a common driving force in malignant melanoma. Thus, V600E may represent an alternative to KIT- and PDGFRA-activation as a molecular mechanism of GIST pathogenesis. Although, BRAF-mutated GISTs show predilection for an intestinal location, no specific pathologic features defining this subgroup have been reported yet. BRAF inhibitors might be considered in treatment of metastatic and locally advanced BRAF-mutant GISTs. 92–95

-

-

What is now known as GIST, used to be called gastrointestinal (GI) smooth muscle tumor: leiomyoma if benign, leiomyosarcoma if malignant, and leiomyoblastoma if with epithelioid histology.

-

-

GISTs typically occur in older adults, and the median patient age in the major series has varied between 60–65 years.

-

-

Most GISTs, approximately 85–90%, contain oncogenic KIT or platelet derived growth factor receptor (PDGFRA) mutations.

-

-

Most common clinical symptoms of GIST are GI bleeding and gastric discomfort or ulcer-like symptoms.

-

-

Wedge resection is the most common surgery for a small to medium-sized gastric GIST and sufficient margins can usually be obtained.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Welsh RA, Meyer AT. Ultrastructure of gastric leiomyoma. Arch Pathol. 1969;87:71–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Evans DJ, Lampert IA, Jacobs M. Intermediate filaments in smooth muscle tumors. J Clin Pathol. 1983;36:57–61. doi: 10.1136/jcp.36.1.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mazur MT, Clark HB. Gastric stromal tumors. Reappraisal of histogenesis. Am J Surg Pathol. 1983;7 doi: 10.1097/00000478-198309000-00001. 5-7-519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hirota S, Isozaki K, Moriyama Y, et al. Gain-of-function mutations of c-kit in human gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Science. 1998;279:577–580. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5350.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kindblom LG, Remotti HE, Aldenborg F, et al. Gastrointestinal pacemaker cell tumor (GIPACT). Gastrointestinal stromal tumors show phenotypic characteristics of the interstitial cells of Cajal. Am J Pathol. 1998;153:1259–1269. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nilsson B, Bumming P, Medis-Kindblom JM, Oden A, Dortok A, Gustavsson B, Sablinska K, Kindblom LG. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: the incidence, prevalence, clinical course, and prognostication in the preimatinib mesylate era – a population-basede study in western Sweden. Cancer. 2005;103:821–829. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tryggvason G, Gislason HG, Magnusson MK, Jonasson JG. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors in Iceland, 1990–2003: the Icelandic GIST study, a population-based incidence and pathologic risk stratification study. Int J Cancer. 2005;117:289–293. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abraham SC, Krasinskas AM, Hofstetter WL, Swisher SG, Wu TT. « Seedling » mesenchymal tumors (gastrointestinal stromal tumors and leiomyomas) are common in cidental tumors of thevesophagogastric junction. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:1629–1635. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31806ab2c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agaimy A, Wunsch PH, Hofstaedter F, Blaszyk H, Rummele P, Gaumann A, Dietmaier W, Hattmann A. Minute sclerosing stromal tumors (GIST tumorlets) are common in adults and frequently show KIT mutations. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:113–120. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000213307.05811.f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mendoza-Marin M, Hoang MP, Albores-Saavedra J. Malignant stromal tumor of the gallbladder with interstitial cells of Cajal phenotype. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2002 Apr;126:481–483. doi: 10.5858/2002-126-0481-MSTOTG. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park JK, Choi SH, Lee S, Min KO, Yun SS, Jeon HM. Malignant gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the gallbladder. J Korean Med Sci. 2004;1:763–767. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2004.19.5.763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Daraji WI, Makhlouf HR, Miettinen M, Montgomery EA, Goodman ZD, Marwaha JS, Fanburg-Smith JC. Primary gallbladder sarcoma: a clinicopathologic study of 15 cases, heterogeneous sarcomas with poor outcome, except pediatric botryoid rhabdomyosarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;3:826–834. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181937bb3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herawi M, Montgomery EA, Epstein JI. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) on prostate needle biopsy: A clinicopathologic study of 8 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:1389–1395. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000209847.59670.c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huizinga JD, Thuneberg L, Kluppel M, et al. W/kit gene required for interstitial cells of Cajal and for intestinal pacemaker activity. Nature. 1993;373:347–349. doi: 10.1038/373347a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Torihashi S, Nishi K, Tokutomi Y, et al. Blockade of kit signaling induces transdifferentiation of interstitial cells of Cajal to a smooth muscle phenotype. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:140–148. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70560-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kitamura Y, Hirota S. Kit as a human oncogenic tyrosine kinase. Review. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2004;61:2924–2931. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-4273-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fletcher JA, Rubin BP. KIT mutations in GIST. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2007;17:3–7. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2006.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lasota J, Miettinen M. Clinical significance of oncogenic KIT and PDGFRA mutations in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Histopathology. 2008;53:245–266. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2008.02977.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Corless CL, Barnett CM, Heinrich MC. Gastrointestinal stromal tumours: origin and molecular oncology. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;1:865–878. doi: 10.1038/nrc3143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taniguchi M, Nishida T, Hirota S, Isozaki K, Ito T, Nomura T, et al. Effect of c-kit mutation on prognosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Cancer Res. 1999;59:4297–4300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rubin BP, Singer S, Tsao C, Duensing A, Lux ML, Ruiz R, Hibbard MK, Chen CJ, Xiao S, Tuveson DA, Demetri GD, Fletcher CD, Fletcher JA. KIT activation is a ubiquitous feature of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Cancer Res. 2001;61:8118–8121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Demetri GD. Targeting c-kit mutations in solid tumors: scientific rationale and novel therapeutic options. Semin Oncol. 2001;28(5 Suppl 17):19–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Longley BJ, Reguera MJ, Ma Y. Classes of c-KIT activating mutations: proposed mechanisms of action and implications in disease classification and therapy. Leuk Res. 2001;25:571–576. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(01)00028-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wardelmann E, Losen I, Hans V, Neidt I, Speidel N, Bierhoff E, Heinicke T, Pietsch T, Buttner R, Merkelbach-Bruse S. Deletion of Trp-557 and Lys-558 in the juxtamembrane domain of the c-kit protooncogene is associated with metastatic behavior of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Int J Cancer. 2003;106:887–895. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martín J, Poveda A, Llombart-Bosch A, et al. Deletions affecting codons 557–558 of the c-KIT gene indicate a poor prognosis in patients with completely resected gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a study by the Spanish Group for Sarcoma Research (GEIS) J Clin Oncol. 2005 Sep 1;23(25):6190–6198. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.19.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miettinen M, Sobin LH, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the stomach: A clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic studies of 1765 cases with long-term follow-up. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:52–68. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000146010.92933.de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lasota J, Dansonka-Mieszkowska A, Stachura T, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors with internal tandem duplications in 3' end of KIT juxtamembrane domain occur predominantly in stomach and generally seem to have a favorable course. Mod Pathol. 2003;16:1257–1264. doi: 10.1097/01.MP.0000097365.72526.3E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Antonescu CR, Sommer G, Sarran L, et al. Association of KIT exon 9 mutations with nongastric primary site and aggressive behavior: KIT mutation analysis and clinical correlates of 120 gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:3329–3337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lasota J, Kopczynski J, Sarlomo-Rikala M, et al. KIT 1530ins6 mutation defines a subset of predominantly malignant gastrointestinal stromal tumors of intestinal origin. Hum Pathol. 2003;34:1306–1312. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(03)00407-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sakurai S, Oguni S, Hironaka M, Fukayama M, Morinaga S, Saito K. Mutations in c-kit gene exons 9 and 13 in gastrointestinal stromal tumors among Japanese. Jpn J Cancer Res. 2001;92:494–498. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2001.tb01121.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Debiec-Rychter M, Sciot R, Le Cesne A, et al. KIT mutations and dose selection for imatinib in patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumours. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42:1093–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marrari A, Trent JC, George S. Personalized cancer therapy for gastrointestinal stromal tumor: synergizing tumor genotyping with imatinib plasma levels. Curr Opin Oncol. 2010 Jul;22:336–341. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e32833a6b8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miettinen M, Makhlouf HR, Sobin LH, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) of the jejunum and ileum – a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical and molecular genetic study of 906 cases prior to imatinib with long-term follow-up. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;31:477–489. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200604000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lux ML, Rubin BP, Biase TL, Chen CJ, Maclure T, Demetri G, Xiao S, Singer S, Fletcher CD, Fletcher JA. KIT extracellular and kinase domain mutations in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:791–795. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64946-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lasota J, Corless CL, Heinrich MC, Debiec-Rychter M, Sciot R, Wardelmann E, et al. Clinicopathologic profile of gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) with primary KIT exon 13 or exon 17 mutations: a multicenter study of 54 cases. Mod Pathol. 2008;21:476–484. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2008.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heinrich MC, Corless CL, Duensing A, et al. PDGFRA activating mutations in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Science. 2003;299:708–710. doi: 10.1126/science.1079666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lasota J, Miettinen M, Lasota J, Dansonka-Mieszkowska A, Sobin LH, et al. A great majority of GISTs with PDGFRA mutations represent gastric tumors with low or no malignant potential. Lab Invest. 2004;84:874–883. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Corless CL, Schroeder A, Griffith D, Town A, McGreevey L, Harrell P, Shiraga S, Bainbridge T, Morich J, Heinrich MC. PDGFRA mutations in gastrointestinal stromal tumors: frequency, spectrum and in vitro sensitivity to imatinib. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5357–5364. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.14.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Levy AD, Remotti HE, Thompson WM, Sobin LH, Miettinen M. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: radiologic features with pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2003;23:283–304. doi: 10.1148/rg.232025146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vander Noot MR, 3rd, Eloubeidi MA, Chen VK, et al. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal tract lesions by endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy. Cancer. 2004;102:157–163. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.DeWitt J, Emerson RE, Sharman S, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided trucut biopsy of gastrointestinal mesenchymal tumor. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:192–202. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1522-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sarlomo-Rikala M, Kovatich A, Barusevicius A, et al. CD117: A sensitive marker for gastrointestinal stromal tumors that is more specific than CD34. Mod Pathol. 1998;11:728–734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hornick JL, Fletcher CD. Immunohistochemical staining fo KIT (CD117) in soft tissue sarcomas is very limited in distribution. Am J Clin Pathol. 2002;117:188–193. doi: 10.1309/LX9U-F7P0-UWDH-8Y6R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Medeiros F, Corless CL, Duensing A, Hornick JL, Oliveira AM, Heinrich MC, Fletcher JA, Fletcher CD. KIT-negative gastrointestinal stromal tumors: proof of concept and therapeutic implications. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:889–894. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200407000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lasota J, Stachura J, Miettinen M. GISTs with PDGFRA exon 14 mutations represent subset of clinically favorable gastric tumors with epithelioid morphology. Lab Invest. 2006;86:94–100. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hwang SJ, Blair PJ, Britton FC, et al. Expression of anoctamin 1/TMEM16A by interstitial cells of Cajal is fundamental for slow wave activity in gastrointestinal muscles. J Physiol. 2009;587:4887–4904. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.176198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.West RB, Corless CL, Chen X, et al. The novel marker, DOG1, is expressed ubiquitously in gastrointestinal stromal tumors irrespective of KIT or PDGFRA mutation status. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:107–113. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63279-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miettinen M, Wang ZF, Lasota J. DOG1 antibody in the differential diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a study of 1840 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1401–1408. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181a90e1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Duensing A, Joseph NE, Medeiros F, et al. Protein kinase C theta (PKCtheta) expression and constitutive activation in gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) Cancer Res. 2004;64:5127–5131. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Motegi A, Sakurai S, Nakayama H, et al. PKC theta, a novel immunohistochemical marker for gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST), especially useful for identifying KIT-negative tumors. Pathol Int. 2005;55:106–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2005.01806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Miettinen M, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: pathology and prognosis at different sites. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2006;23:70–83. doi: 10.1053/j.semdp.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gold JS, Gönen M, Gutiérrez A, et al. Development and validation of a prognostic nomogram for recurrence-free survival after complete surgical resection of localised primary gastrointestinal stromal tumour: a retrospective analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:1045–1052. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70242-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.El-Rifai W, Sarlomo-Rikala M, Andersson L. DNA sequence cop number changes in gastrointestinal stromal tumors tumor progression and prognostic significance. Cancer Res. 2000;60:3899–3903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lagarde P, Perot G, Kauffmann A, et al. Mitotic checkpoints and chromosome instability are strong predictors of clinical outcome in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:826–838. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McCarter MD, Antonescu CR, Ballman KV, et al. Microscopically positive margins for primary gastrointestinal stromal tumors: analysis of risk factors and tumor recurrence. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;215:53–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Catena F, DiBattista M, Ansaloni L, et al. Microscopic margins of resection influence primary gastrointestinal stromal tumor survival. Onkologie. 2012;35:645–648. doi: 10.1159/000343585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Novitsky YV, Kercher KW, Sing RF, et al. Long-term outcomes of laparoscopic resection of gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Ann Surg. 2006;243:738–745. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000219739.11758.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Otani Y, Furukawa T, Yoshida M, et al. Operative indications for relatively small (2–5 cm) gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the stomach based on analysis of 60 operated cases. Surgery. 2006;139:484–492. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2005.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Karakousis GC, Singer S, Zheng J, et al. Laparoscopic varsus open gastric resections for primary gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs): a size-matched comparison. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:1599–1605. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1517-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pucci MJ, Berger AC, Lim PW, et al. Laparoscopic approaches to gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors: an institutional review of 57 cases. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:3509–3514. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2374-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sasaki A, Koeda K, Obuchi T, et al. Tailored laparoscopic resection for suspected gastri gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Surgery. 147:516–520. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.10.035. 201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rutkowski P, Ruka W. Emergency surgery in the era of molecular treatment of solid tumours. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:157–163. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mabille M, Vanel D, Albiter M, et al. Follow-up of hepatic and peritoneal metastases of gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) under imatinib therapy requires different criteria of radiologic evaluation (size is not everything!!!) Eur J Radiol. 2009;69:204–208. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Joensuu H, Roberts PJ, Sarlomo-Rikala M, et al. Effect of tyrosine kinase inhibitor STI571 in a patient with metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1052–1056. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104053441404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Reichardt P, Blay JY, Boukovinas I, et al. Adjuvant therapy in primary GIST: state of the art. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:2776–2781. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Casali PG, Fumagalli E, Gronchi A. Adjuvant therapy of gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2012;13:277–284. doi: 10.1007/s11864-012-0198-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Demetri GD, von Mehren M, Antonescu CR, et al. NCCN task force report: update on the management of patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2010;8(Suppl 2):S1–S41. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2010.0116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dematteo RP, Ballman KV, Antonescu CR, et al. Adjuvant mesylate after resection of localised, primary gastrointestinal stromal tumor: a randomized, double-bling, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;373:1097–1104. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60500-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Joensuu H, Eriksson M, Sundby Hall K, et al. One vs. three years of adjuvant imatinib for operable gastrointestinal stromal tumor: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;307:1265–1272. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Demetri GD. Differential properties of current tyrosine kinase inhibitors in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Semin Oncol. 2011;38(Suppl1):S10–S19. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2011.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shoffski P, Reichardt P, Blay JY, et al. A phase II study of evelolimus (RAD001) in combination with imatinib in in patients with imatinib-resistant gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:1990–1998. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Smyth T, van Looy T, Curry JE, et al. The HSP inhibitor, AT13387, is effective against imatinib-sensitive and resistant gastrointestinal stromal tumor models. Mol Cancer Ther. 2012;11:1799–1808. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sambol EB, Ambrosini G, Geha RC, et al. Flavopiridol targets c-KIT transcription and induces apoptosis in gastrointestinal stromal tumor cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:5858–5866. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Veiga I, Silva M, Vieira J, et al. Hereditary gastrointestinal stromal tumors sharing the KIT Exon 17 germline mutation p.Asp820Tyr develop through different cytogenetic progression pathways. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2010;49:91–98. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Janeway KA, Kim SY, Lodish M, et al. Defects in succinate dehydrogenase in gastrointestinal stromal tumors lacking KIT and PDGFRA mutations. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2011;108:314–318. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009199108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Stratakis CA, Carney JA. The triad of paragangliomas, gastric stromal tumours, and pulmonary chondromas (Carney triad), and the dyad of paragangliomas and gastric stromal sarcomas (Carney-Stratakis syndrome): molecular genetics and clinical implications. J Int Med. 2009;266:43–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2009.02110.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pasini B, McWhinney SR, Bei T, et al. Clinical and molecular genetics of patients with the Carney-Stratakis syndrome and germline mutations of the genes coding for the succinate dehydrogenase subunits SDHB, SDHC, and SDHD. Eur J Human Genet. 2008;16:79–88. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Miettinen M, Wang ZF, Sarlomo-Rikala M, et al. Succinate dehydrogenase-deficient GISTs: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study of 66 gastric GISTs with predilection to young age. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:1712–1721. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182260752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Miettinen M, Killian JK, Wang ZF, et al. immunohistochemical loss of succinate dehydrogenase subunit a (sdha) in gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) signals SDHA germline mutation. Am J Surg Pathol. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182671178. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gill AJ, Chou A, Vilain R, et al. Immunohistochemistry for SDHB divides gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) into 2 distinct types. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:805–814. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181d6150d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gaal J, Stratakis CA, Carney JA, et al. SDHB immunohistochemistry: a useful tool in the diagnosis of Carney-Stratakis and Carney triad gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:147–151. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pantaleo MA, Astolfi A, Indio V, et al. SDHA loss-of-function mutations in KIT-PDGFRA wild-type gastrointestinal stromal tumors identified by massively parallel sequencing. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:1–5. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Dwight T, Benn DE, Clarkson A, et al. Loss of SDHA expression identifies SDHA mutations in succinase dehydrogenase-deficient gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012 doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182671155. Epub Oct 10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wagner AJ, Remillard SP, Zhang YX, et al. Loss of SDHAS predicts SDHA mutations in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Mod Pathol. 2012 doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.153. Epub Sept 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Carney JA, Stratakis CA. Familial paraganglioma and gastric stromal sarcoma: a new syndrome distinct from the Carney triad. Am J Med Genet. 2002;108:132–139. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.10235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zhang L, Smyrk TC, Young WF, Stratakis CA, Carney JA. Gastric stromal tumors in Carney triad are different clinically, pathologically, and behaviorally from sporadic gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors: Findings in 104 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:53–64. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181c20f4f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Agaram NP, Laquaglia MP, Ustun P, et al. Molecular characterization of pediatric gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:3204–3215. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Pappo AS, Janeway K, Laquaglia M, Kim SY. Special considerations in pediatric gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J Surg Oncol. 2011;104:928–932. doi: 10.1002/jso.21868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Andersson J, Sihto H, Meis-Kindblom JM, et al. NF1-associated gastrointestinal stromal tumors have unique clinical, phenotypic, and genotypic characteristics. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:1170–1176. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000159775.77912.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kinoshita K, Hirota S, Isozaki K, Ohashi A, Nikshida T, Kitamura Y, Shinomura Y, Matsuzawa Y. Absence of c-kit gene mutations in gastrointestinal stromal tumours from neurofibromatosis type 1 patients. J Pathol. 2004;202:80–85. doi: 10.1002/path.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Miettinen M, Fetsch JF, Sobin LH, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors in patients with neurofibromatosis 1. A clinicopathologic study of 45 patients with long-term follow-up. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:90–96. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000176433.81079.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Agaram NP, Wong GC, Guo T, et al. Novel V600E BRAF mutations in imatinib-naive and imatinib-resistant gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2008;47:853–859. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Agaimy A, Terracciano LM, Dirnhofer S, et al. V600E BRAF mutations are alternative early molecular events in a subset of KIT/PDGFRA wild-type gastrointestinal stromal tumours. J Clin Pathol. 2009;62:613–616. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2009.064550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hostein I, Faur N, Primois C, et al. BRAF mutation status in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Am J Clin Pathol. 2010;133:141–148. doi: 10.1309/AJCPPCKGA2QGBJ1R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Daniels M, Lurkin I, Pauli R, Erbstösser E, Hildebrandt U, Hellwig K, Zschille U, Lüders P, Krüger G, Knolle J, Stengel B, Prall F, Hertel K, Lobeck H, Popp B, Theissig F, Wünsch P, Zwarthoff E, Agaimy A, Schneider-Stock R. Spectrum of KIT/PDGFRA/BRAF mutations and Phosphatidylinositol-3-Kinase pathway gene alterations in gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) Cancer Lett. 2011;312:43–54. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]