Abstract

Background

The hystricognath rodents of the New World, the Caviomorpha, are a diverse lineage with a long evolutionary history, and their representation in South American fossil record begins with their occurrence in Eocene deposits from Peru. Debates regarding the origin and diversification of this group represent longstanding issues in mammalian evolution because early hystricognaths, as well as Platyrrhini primates, appeared when South American was an isolated landmass, which raised the possibility of a synchronous arrival of these mammalian groups. Thus, an immediate biogeographic problem is posed by the study of caviomorph origins. This problem has motivated the analysis of hystricognath evolution with molecular dating techniques that relied essentially on nuclear data. However, questions remain about the phylogeny and chronology of the major caviomorph lineages. To enhance the understanding of the evolution of the Hystricognathi in the New World, we sequenced new mitochondrial genomes of caviomorphs and performed a combined analysis with nuclear genes.

Results

Our analysis supports the existence of two major caviomorph lineages: the (Chinchilloidea + Octodontoidea) and the (Cavioidea + Erethizontoidea), which diverged in the late Eocene. The Caviomorpha/phiomorph divergence also occurred at approximately 43 Ma. We inferred that all family-level divergences of New World hystricognaths occurred in the early Miocene.

Conclusion

The molecular estimates presented in this study, inferred from the combined analysis of mitochondrial genomes and nuclear data, are in complete agreement with the recently proposed paleontological scenario of Caviomorpha evolution. A comparison with recent studies on New World primate diversification indicate that although the hypothesis that both lineages arrived synchronously in the Neotropics cannot be discarded, the times elapsed since the most recent common ancestor of the extant representatives of both groups are different.

Keywords: Caviomorpha, Phiomorpha, Platyrrhini, Mitochondrial genome, Supermatrix, Bayesian relaxed clock

Background

New World Hystricognathi (NWH, Caviomorpha) consists of a diverse assemblage of rodents that represent a unique level of ecological and morphological diversification among extant Rodentia. In size, caviomorphs vary from the largest living rodent, the capybara (Hydrochoerus), to the tiny degus (Octodon). The species in the lineage have exploited habitats as different as those used by the fossorial tuco-tuco (Ctenomys), the arboreal spiny rats (Echimyidae), the grazers such as the mara (Dolichotis) and the semi-aquatic capybara. Even representative species that were domesticated by humans, such as the chinchilla and the widely known guinea pig (Cavia), are found among NWH.

Despite their morphological and ecological diversity in the Neotropics, hystricognaths are not members of the endemic South American mammalian fauna. As didactically characterized by Simpson [1], caviomorphs, together with New World Primates (NWP, Platyrrhini), are part of the second major stage of South American mammal evolution [2]. They reached the New World during the Eocene, most likely by a transatlantic route from Africa [3]. This scenario is supported by the phylogenetic affinity of NWH with African hystricognath rodents (phiomorphs), particularly the families Thryonomyidae, Petromuridae and Bathyergidae [4]. Furthermore, the earliest record of caviomorphs in the New World is dated at approximately 41 Ma [5], when the South American continent was an isolated landmass.

Because of the evident biogeographical appeal of the topic, the evolution of Caviomorpha has motivated several studies that estimated divergence times, especially those using relaxed molecular clock techniques, to obtain a precise timescale for the origin of NWH [6-9]. Moreover, the close association of NWH evolutionary history with the origin of Neotropical primates, which also evolved from African ancestors that reached South America during the Eocene, has encouraged the comparative analysis of the problem [10,11].

The ages of the diversification events within NWH, however, have garnered comparatively less attention than the age of the separation of the Caviomorpha from African phiomorphs. Paleontological findings support the hypothesis that the diversification of caviomorphs consisted of a rapid event because the majority of the extant families were already present in the fossil record of the Deseadan (from 29 to 21 Ma, late Oligocene/early Miocene) [12]. Thus, if the earliest NWH fossils have an age of 41 Ma, the radiation of extant caviomorph families occurred approximately from the late Eocene to late Oligocene interval. This history indicates that the early divergences that produced supra-familial groupings may have occurred soon after the arrival of the ancestral stock.

In addition, there remain unresolved issues related to NWH macroevolution. Although the four major caviomorph lineages, the Cavioidea, Chinchilloidea, Erethizontoidea and Octodondoidea, which were ascribed to superfamilies by Woods [13], have been recovered in molecular phylogenetic analyses [4,8], the evolutionary affinities among these lineages are not consensual. For example, the first analyses based on molecular data identified the Erethizontoidea as the sister lineage of the (Chinchilloidea + Octodontoidea) clade and indicated the exclusion of the Cavioidea as a sister to all extant caviomorph superfamilies [4,6]. Recently, however, based on the analysis of additional genes, it appears that NWH consists of two major evolutionary lineages, the (Chinchilloidea + Octodontoidea) and the (Erethizonthoidea + Cavioidea) [7,14], although Rowe et al. [8] could not assign the Erethizontoidea to either the Cavioidea or the (Chinchilloidea + Octodontoidea) clade with statistical support.

Therefore, the early evolution of NWH raises issues that require further investigation to allow a deeper understanding of the geoclimatic factors that acted on the history of the group. Accordingly, the phylogenetic relationships among caviomorph superfamilies and the chronological setting in which the early diversification occurred are fundamental information for proposing consistent hypotheses about NWH origins. To achieve this goal, molecular data have been used successfully over the past decade. In this study, we increased the amount of mitochondrial data by sequencing the mitochondrial genomes of Chinchilla lanigera (Chinchilloidea), Trinomys dimidiatus (Octodontoidea) and Sphiggurus insidiosus (Erethizontoidea). The choice of mitochondrial markers is based on the recognition that the majority of molecular studies on Caviomorpha relied fundamentally on nuclear genes. Previous studies have already sequenced mitochondrial genomes of cavioids [15] and other octodontoids [16]. Therefore, the mitochondrial genomes of all NWH superfamilies were sampled.

We show that the combined analysis of nuclear genes and mitochondrial genomes supports the association of Erethizontoidea with Cavioidea and the separation of these associated taxa from the (Chinchilloidea + Octodontoidea) clade. The diversification of Caviomorpha from the African phiomorphs occurred approximately 43 Ma, and the early evolution of the major lineages occurred in the late Eocene. In contrast, family-level divergences occurred in the early Miocene, as supported by fossil record of the caviomorphs.

Results

The Trinomys dimidiatus, Chinchilla lanigera and Sphiggurus insidiosus mitochondrial genomes were 16,533 bp, 16,580 bp and 16,571 bp long, respectively. The genomes presented the same gene order found in other mammals. The observed base frequencies were: fA = 33.4%, fC = 25.4%, fG =13.5% and fT = 27.7%, in the T. dimidiatus mitochondrial genome. In the C. lanigera mitochondrial genome the values were: fA = 33.4%, fC = 27.8%, fG =13.1% and fT = 25.8%. Finally, in the S. insidiosus mitochondrial genome, the base frequencies were: fA = 33.5%, fC = 22.7%, fG =12.5% and fT = 31.2%. These values are close to the average base frequencies estimated from the previously available hystricognath mitogenomes (fA = 31.9%, fC = 25.2%, fG =12.3% and fT = 30.7%).

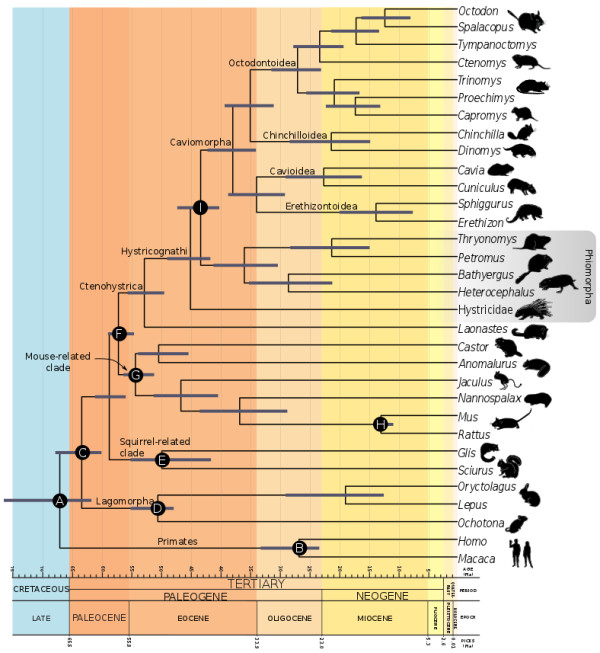

All nodes of the inferred phylogeny were supported by 100% Bayesian posterior clade probability (BP), except for the divergence within the Echimyidae. The separation of Rodentia and Lagomorpha was estimated to have occurred at 63.4 Ma (Figure 1). The first rodent offshoot was composed of the Sciuromorpha. This event was inferred to have occurred at 58.8 Ma, in the late Paleocene. The split of the Hystrocognathi from other rodent lineages was also estimated in the late Paleocene, at 57.2 Ma (100% BP). The diversification of the Castor/Anomalurus lineage from myomorph rodents was inferred to have occurred in the early Eocene, at 54.4 Ma. The Castorimorpha/Anomaluromorpha split was also estimated in the early Eocene (50.4 Ma). All other myomorph splits studied, with the exception of the Mus/Rattus separation, were also inferred to have occurred in the Eocene.

Figure 1.

Timescale for hystricognath evolution. Statistical support for all nodes is 100% BP, except for the Capromys + Proechimys association, which is supported by 68% BP. Bars on nodes indicate the 95% credibility interval. Letters on nodes indicate the calibration information used.

Within Hystricomorpha, the separation of the Diatomyidae, represented by Laonastes, from other hystricognath rodents was inferred in the early Eocene (52.8 Ma). We recovered the Phiomorpha as a paraphyletic assemblage, consisting of Hystricidae and a clade with the remaining, strictly African-distributed, phiomorphs. This basal split between phiomorphs was inferred at 45.1 Ma (late Eocene). The New World Hystricognathi was recovered as monophyletic and sister to the phiomorph clade distributed exclusively in Africa. The separation between Old World and New World Hystricognathi was estimated to have occurred at 43.3 Ma, in the middle Eocene.

The basalmost split within the Caviomorpha consisted of the separation of the (Cavioidea + Erethizontoidea) superfamilies from the (Chinchilloidea + Octodontoidea). This split age was estimated from the middle to late Eocene, at 37.9 Ma. The Chinchilloidea/Octodontoidea divergence was inferred at 35.0 Ma (late Eocene), while the Cavioidea/Erethizontoidea separation also was inferred to have occurred at the end of the Eocene epoch (33.9 Ma). The oldest separation was that between (Echimyidae + Capromyidae) and (Octodontidae + Ctenomyidae) lineages, within Octodontoidea, which age was estimated at 27 Ma (late Oligocene). Family-level cladogenetic events were estimated to took place in the early Miocene epoch. Within octodontoids, the Ctenomyidae and Octodontidae divergence was inferred at 23.4 Ma, and the Capromyidae separation from the paraphyletic Echimyidae was estimated to have occurred at 17.2 Ma. Echimyidae paraphyly is weakly supported because the (Capromys + Proechimys) BP was 68%. The age of the separation between Dinomyidae and Chinchillidae, within chinchilloids, was inferred as 21.3 Ma. In cavioids, the Cuniculidae and Caviidae likely diverged in the early Miocene at 22.6 Ma. Diversification at the genus level probably occurred from the middle to the late Miocene.

Discussion

The chronology of NWH evolution inferred from the combined analysis of mitochondrial genomes and nuclear data is compatible with the paleontological scenario recently proposed by Antoine et al. (2012). Note that these authors have also suggested that the caviomorph-phiomorph separation occurred at approximately 43 Ma, which is identical to our estimate. Our results are also consistent with the latest molecular analyses [7,8,14]. Therefore, the general pattern of caviomorph evolution is replicated by different analytical approaches. This outcome suggests that a consensus may have been reached. It is worth noting that our timescale is also in agreement with the recent hystricognath fossil findings from the Yahuarango Formation in Peruvian Amazonia. The fauna recovered from this formation, which yielded the first caviomorph record in the New World, is composed of animals with fundamentally plesiomorphic tooth morphology that resembles the early Afro-Asian phiomorphs from the middle Eocene (Antoine et al. 2012). These animals therefore represent the early stages of NWH evolution and are most likely not directly related to any of the extant lineages. This hypothesis is consistent with our findings because the extant lineages diversified after 37.6 Ma according to our timescale.

In terms of the general pattern of diversification, the Caviomorpha evolved from an African hystricognath lineage in the middle Eocene. The extant (Thryonomyidae + Petromuridae), Bathyergidae) clade consists of its phiomorph sister group, excluding the living Hystricidae, which may descend from the first phiomorph radiation. This phylogenetic arrangement was first proposed by Huchon and Douzery [4]. Within Caviomorpha, the relationship between cavioids and erethizontoids is perhaps the most unusual hypothesis suggested by the molecular data. For example, McKenna and Bell [17] excluded the erethizontoids from the major Neotropical radiation of Hystricognathi, dubbed Caviida by those authors, which included octodontoids, chinchilloids and cavioids. In our study, the position of Erethizontoidea as the sister group of the Cavioidea is statistically supported and is consistent with previous analyses [7,14]. We used the KH [18] and SH tests [19] to evaluate the statistical significance of the difference in log-likelihoods between our hypothesis and that of an alternative phylogeny that placed Erethizontoids with the (Octodontoidea + Chinchilloidea) clade. Both tests rejected the null hypothesis that the log-likelihoods of both phylogenies are equal (p < 0.05) in favor of the topology inferred in this study.

In addition, our phylogenetic hypothesis also corroborates an African origin of Caviomorpha. The age of the separation of NWH from African phiomorphs (43.3 Ma) is also in agreement with previous studies based primarily on nuclear data. Because the diversification of the first Neotropical hystricognath lineages occurred at 37.6 Ma, the colonization of the South American island continent must have occurred at some time before the middle Eocene. If this conclusion is correct, a transatlantic dispersal route was used. It is possible that this dispersal occurred as a result of island hopping along an island corridor [20] or even by floating islands, which, at least for primates, is a possibility to be considered [21].

Although a general consensus has been reached on the African origin of NWH [8,14,22], it is worth mentioning that an alternative hypothesis for the origin of caviomorphs was proposed by A. E. Wood [23], who considered the North American “Franimorpha” the possible ancestral stock of South American hystrichognaths. This association was based on the putative hystricomorphous condition of North American Eocene species such as Platypittamys. However, this hypothesis was primarily questioned by René Lavocat [3,24], who supported an African origin of caviomorphs. Recently, Martin [25] showed that the enamel microstructure of caviomorph teeth is similar to that found in certain African phiomorphs. Moreover, it is now generally considered that franimorphs were actually protogomorph rodents, with no association with the radiation of caviomorphs [26].

As previously stated, because of the biogeographic importance of the problem, it is customary to perform studies on NWH evolution in conjunction with a comparative analysis of the evolution of the Neotropical primates. The latest extensive analysis of primate evolution, conducted by Perelman et al. [27], inferred that the New World Platyrrhini/Old World Catarrhini separation occurred at 43.5 Ma. This value is statistically identical to the age of the caviomorph-phiomorph split estimated here. These estimates agree with the recent analysis of Loss-Oliveira et al. [11] and the earlier proposal by Poux et al. [10], who showed that the available molecular data cannot reject the hypothesis of a synchronous arrival of hystricognaths and primates in the New World.

As noted by Antoine et al. [5], the evolutionary history of anthropoids and hystricognaths is curiously linked. Both groups are hypothesized to have evolved in Asia and then to have invaded Africa from the early to middle Eocene [28]. As molecular data suggest, the probability of a single colonization event involving the isolated South American continent is high. However, paleontological findings on primates support a later arrival of anthropoids [29]. The lag between the first hystricognaths and the first representative of the Platyrrhini, Branisella sp., is close to 15 Ma [5]. Because molecular data represent the time of genetic separation of lineages, it is possible that the Platyrrhini/Catarrhini divergence may not be associated with the dispersal event from Africa to South America. In this scenario, the genetic separation would have occurred on the African continent, with a subsequent dispersal of anthropoids to the Neotropics. This hypothesis would imply that fossil anthropoids with platyrrhine characteristics should occur in Africa. Actually, as Fleagle [30] reported, fossils recovered from the Eocene deposit of Fayum, Egypt, show certain NWP attributes. Nevertheless, these attributes may represent the plesiomorphic anthropoid morphology and would only indicate that NWP morphology remained plesiomorphic during its evolutionary history.

Another important issue is that, in contrast to the value for the Hystricognathi, the time to the most recent common ancestor of extant NWP is inferred to be ca. 20 Ma, in the early Miocene [27,31,32]. Therefore, the living NWP are the descendants of a younger stock than the caviomorphs. This finding implies that the pattern of lineage extinction was distinct in both groups. This topic has been investigated recently by Kay et al. [33], who proposed that Branisella and several NWP fossils from the Miocene deposits of the southern region of South America represent an independent radiation, not related to any of the extant Platyrrhini lineages. In caviomorphs, however, the early Oligocene record is already associated with one of the major extant lineages [5,34,35].

Conclusion

In conclusion, the chronology of NWH evolution inferred from the combined analysis of nuclear genes and mitochondrial genomes indicates that Caviomorpha/phiomorph separation and the early diversification of NWH lineages in South America occurred in the middle Eocene. Extant caviomorphs are composed of two major lineages: the (Chinchilloidea + Octodontoidea) and (Cavioidea + Erethizontoidea). Family-level splits took place in the early Miocene epoch. Compared with New World primates, caviomorph lineages are older, but the hypothesis of a single colonization event cannot be discarded.

Methods

Total genomic DNA was obtained from fresh or ethanol-preserved fragments of hepatic tissue from three specimens: Trinomys dimidiatus (the soft-spined Atlantic spiny-rat, field number JFV224, accession number JX312694), Chinchilla lanigera (the chinchilla, JFV368, accession number JX312692) and Sphiggurus insidiosus (the Bahia hairy dwarf porcupine, JFV386, accession number JX312693). Genomic DNA was extracted with QIAamp® DNA Mini and Blood Mini kit. DNA was quantified with a NanoDrop spectrophotometer. Paired-end sequencing was performed with the Illumina HiSeq 2000 platform by Fasteris (http://www.fasteris.com). The mitochondrial genome was de novo assembled using the CLC Genomics Workbench 5.1 program with default settings. Sample collection was performed following the national guidelines and provisions of IBAMA (Instituto Brasileiro do Meio Ambiente e dos Recursos Naturais Renováveis, Brazil), under permit number 109/2006. Therefore, all animal procedures were conducted under the jurisprudence of the Brazilian Ministry of Environment and its Ethical Committee. This study does not involve laboratory work on living animals.

Evolutionary analysis

The species used in this study, as well as accession numbers, are listed in Table 1. In addition to NWH, we included representatives of several lineages of Glires and rooted the tree with primate outgroups. Mitochondrial genomes were analyzed by selecting the 13 protein-coding genes. We also studied six publicly available nuclear genes: ADRA2, IRBP, vWF, GHR, BRCA1 and RAG1. The genes were aligned individually in CLUSTALW [36] and then concatenated in a 22,548 bp supermatrix, all three codon positions were included in the matrix. Phylogenetic inference was conducted with MrBayes 3.2 [37] using the GTR + G4 + I model of sequence evolution, which was chosen by the likelihood ratio test implemented in HyPhy [38]. Two independent runs with four chains each (one cold and three hot chains) were sampled every 1,000th generation until 10,000 trees were obtained. A burn-in of 1,000 trees was applied. Chain convergence was monitored by the standard deviation of split frequencies, which reached a plateau at 0.0004, and the potential scale reduction factor statistic, which approached 1.00 for all parameters.

Table 1.

Accession numbers and taxonomic sampling used in this study

Table Footnote: (1) Sciurus vulgaris (adra2b, IRBP), Sciurus aestuans (vWF), Sciurus niger (GHR, BRCA1), Sciurus ignitus (RAG1), Sciurus vulgaris (mitochondrion, complete genome); (2) Anomalurus sp. (A2AB, irbp, vWF, ghr), Anomalurus beecrofti (BRCA1, RAG1), Anomalurus sp. (mitochondrion, complete genome); (3) Trichys fasciculata (A2AB, irbp, VWF), Hystrix africaeaustralis (GHR, BRCA1), Hystrix brachyurus (RAG1), Hystrix indica (CO1) Hystrix cristata (cytb); (4) Cuniculus paca (adra2b, irbp, vWF, GHR), Cuniculus taczanowskii (BRCA1, RAG1), Cuniculus paca (CO1, cytb); (5) Trinomys paratus (vWF), Trinomys iheringi (RAG1), Trinomys dimidiatus (mitochondrion, complete genome); (6) Proechimys oris (vWF), Proechimys longicaudatus (GHR), Proechimys simonsi (RAG1), Proechimys longicaudatus (mitochondrion, complete genome); (7) Octodon lunatus (adra2b, irbp, vWF), Octodon degus (ghr, mitochondrion, complete genome); (8) Ctenomys boliviensis (adra2b, IRBP, vWF, GHR, BRCA1, RAG1), Ctenomys rionegrensis (mitochondrion, partial genome); (9) Sphiggurus melanurus (vWF), Sphiggurus mexicanus (GHR), Sphiggurus insidiosus (mitochondrion, complete genome); (10) Lepus crawshayi (A2AB, irbp, vWF), Lepus capensis (GHR, BRCA1), Lepus europaeus (mitochondrion, complete genome).

Divergence time estimation was performed in the MCMCTree program of the PAML 4.5 package [39] with the multivariate normal approximation [40]. The model of evolutionary rate evolution adopted was the independent lognormal [41]; nucleotide substitutions were modeled by the HKY85 + G6, which is the parameter richer model implemented in MCMCTree. After a burn-in period of 50,000 generations, the Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithm was sampled every 100th generation until 20,000 samples of divergence time parameters were obtained. Detailed prior information for the model parameters is as follows: BDparas = 1 1 0; kappa_gamma = 6 2; alpha_gamma = 1 1; rgene_gamma = 2 2 and sigma2_gamma = 1 10. Convergence of the MCMC runs was measured by the effective sample sizes and the potential scale reduction factor [42].

Calibration information

We have used nine calibration priors to estimate the posterior density of divergence times (Figure 1): (A) The Primates/Glires split was constrained to have occurred between 100.5 and 61.5 Ma [43,44]; (B) Within the Primates, the Homo/Macaca separation was assigned a uniform prior from 34 to 23.5 Ma based on the fossil findings of Proconsul and Catopithecus[45,46]; (C) The Lagomorpha/Rodentia split was assigned a minimum age of 61.5 Ma based on the age of Heomys, an early rodent [43]; (D) Within Lagomorpha, the Leporidae/Ochotonidae split was constrained by a uniform distribution from 48.6 to 65.8 Ma based on the Vastan fossils [47]; (E) The separation of the Sciuromorpha (Sciurus/Glis) from the rest of the rodents was constrained to have occurred between 55.6 and 65.8 Ma based on Sciuravus[48]. (F) The split of Hystricognathi + Laonastes from myomorph and castorimorph rodents was assigned a uniform prior from 52.5 to 58.9 Ma based on Birbalomys, an early hystricognath [49]. (G) The separation of the Castor/Anomalurus lineage from other myomorph rodents was constrained by a uniform distribution from 56.0 to 40.2 Ma according to the fossil finding of Ulkenulastomys, an early myomorph [50]. (H) The Mus/Rattus split was enforced to have occurred between 10.4 and 14 Ma (Karnimata) [51]. (I) Finally, the Caviomorpha/“Phiomorpha” was assigned a minimum age of 40 Ma, based on the recent discoveries of hystricognath rodents from the Yahuarango Formation in Peru [5].

Abbreviations

Ma: Mega annum

Competing interests

Authors declare no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

CMV, JFV, LL-O and CGS carried out the molecular genetic studies, participated in the sequence alignment and drafted the manuscript. CMV and CGS participated in the design of the study and performed the statistical analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Carolina M Voloch, Email: carolvoloch@gmail.com.

Julio F Vilela, Email: julio.vilela@gmail.com.

Leticia Loss-Oliveira, Email: bioloss@gmail.com.

Carlos G Schrago, Email: guerra@biologia.ufrj.br.

Acknowledgments

The authors are greatly indebted to Dr. Cibele R. Bonvicino for reviewing an earlier version of this manuscript. CGS was funded by the Brazilian Research Council-CNPq grant 308147/2009-0 and the Rio de Janeiro State Science Foundation-FAPERJ grants 110.028/2011 and 111.831/2011. LL-O was supported by a scholarship from CNPq. JVF was funded by grant 482914/2011-4 from CNPq and grant 101.822/2011 from FAPERJ.

References

- Simpson GG. Spendid isolation: The curious history od South American mammals. New Haven: Yale University Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Flynn JJ, Wyss AR. Recent advances in South American mammalian paleontology. Trends Ecol Evol. 1998;13(11):449–454. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5347(98)01457-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavocat R. In: Evolutionary Biology of New World Monkeys and Continental Drift. Ciochon RL, Chiarelli BA, editor. New York: Plenum Press; 1980. The implications of rodent paleontology and biogeography to the geographical sources and origin of platyrrhine primates; pp. 93–103. [Google Scholar]

- Huchon D, Douzery EJ. From the Old World to the New World: a molecular chronicle of the phylogeny and biogeography of hystricognath rodents. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2001;20(2):238–251. doi: 10.1006/mpev.2001.0961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoine PO, Marivaux L, Croft DA, Billet G, Ganerod M, Jaramillo C, Martin T, Orliac MJ, Tejada J, Altamirano AJ. Middle Eocene rodents from Peruvian Amazonia reveal the pattern and timing of caviomorph origins and biogeography. Proc R Soc B. 2012;279(1732):1319–1326. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2011.1732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opazo JC. A molecular timescale for caviomorph rodents (Mammalia, Hystricognathi) Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2005;37(3):932–937. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huchon D, Chevret P, Jordan U, Kilpatrick CW, Ranwez V, Jenkins PD, Brosius J, Schmitz J. Multiple molecular evidences for a living mammalian fossil. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(18):7495–7499. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701289104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe DL, Dunn KA, Adkins RM, Honeycutt RL. Molecular clocks keep dispersal hypotheses afloat: evidence for trans-Atlantic rafting by rodents. J Biogeogr. 2010;37(2):305–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2699.2009.02190.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sallam HM, Seiffert ER, Steiper ME, Simons EL. Fossil and molecular evidence constrain scenarios for the early evolutionary and biogeographic history of hystricognathous rodents. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(39):16722–16727. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908702106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poux C, Chevret P, Huchon D, de Jong WW, Douzery EJ. Arrival and diversification of caviomorph rodents and platyrrhine primates in South America. Syst Biol. 2006;55(2):228–244. doi: 10.1080/10635150500481390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loss-Oliveira L, Aguiar BO, Schrago CG. Testing Synchrony in Historical Biogeography: The Case of New World Primates and Hystricognathi Rodents. Evol Bioinforma. 2012;8:127–137. doi: 10.4137/EBO.S9008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan TA, Ryan JM, Czaplewski NJ. Mammalogy. 5. Sudbury: Jones & Bartlett Publishers; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Woods CA. In: Mammalian Biology in South America. Mares M, Genoways H, editor. Pennsylvania: University of Pittsburgh; 1982. The history and classification of South American Hystricognath Rodents: Reflections on the far away and long ago; pp. 377–392. [Google Scholar]

- Blanga-Kanfi S, Miranda H, Penn O, Pupko T, DeBry RW, Huchon D. Rodent phylogeny revised: analysis of six nuclear genes from all major rodent clades. BMC Evol Biol. 2009;9:71. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-9-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DErchia AM, Gissi C, Pesole G, Saccone C, Arnason U. The guinea-pig is not a rodent. Nature. 1996;381(6583):597–600. doi: 10.1038/381597a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomasco IH, Lessa EP. The evolution of mitochondrial genomes in subterranean caviomorph rodents: Adaptation against a background of purifying selection. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2011;61(1):64–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2011.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna MC, Bell SK. Classification of mammals above the species level. New York: Columbia University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kishino H, Hasegawa M. Evaluation of the maximum likelihood estimate of the evolutionary tree topologies from DNA sequence data, and the branching order in Hominoidea. J Mol Evol. 1989;29:170–179. doi: 10.1007/BF02100115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimodaira H, Hasegawa M. Multiple comparisons of log-likelihoods with applications to phylogenetic inference. Mol Biol Evol. 1999;16(8):1114–1116. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira FB, Molina EC, Marroig G. In: South American Primates, Developments in Primatology: Progress and Prospects. Garber PA, Estrada A, Bicca-Marques JC, Heymann EW, editor. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2008. Paleogeography of the South Atlantic: a Route for Primates and Rodents into the New World? [Google Scholar]

- Houle A. The origin of platyrrhines: An evaluation of the Antarctic scenario and the floating island model. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1999;109(4):541–559. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(199908)109:4<541::AID-AJPA9>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janis CM, Dawson MR, Flynn LJ. In: Evolution of Tertiary Mammals of North America: Volume 2, Small Mammals, Xenarthrans, and Marine Mammals. Janis CM, Gunnell GF, Uhen MD, editor. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2008. Glires summary; pp. 263–292. [Google Scholar]

- Wood AE. In: Evolutionary Biology of the New World Monkeys and Continental Drift. Ciochon RL, Chiarelli AB, editor. New York: Plenum Press; 1980. The origin of the caviomorph rodents from a source in Middle America: A clue to the area of origin of the platyrrhine primates; pp. 79–91. [Google Scholar]

- Lavocat R. La systématique des rongeurs hystricomorphes et la dérive des continents. C R Acad Sci Paris Sér D. 1969;269:1496–1497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin T. Incisor schmelzmuster diversity in South America's oldest rodent fauna and early caviomorph history. J Mamm Evol. 2005;12:405–417. doi: 10.1007/s10914-005-6968-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Landry SO Jr. A proposal for a new classification and nomenclature for the Glires (Lagomorpha and Rodentia) Mitteilungen des Museums für Naturkunde, Berlin, Zoologische Reihe. 1999;75:283–316. [Google Scholar]

- Perelman P, Johnson WE, Roos C, Seuanez HN, Horvath JE, Moreira MA, Kessing B, Pontius J, Roelke M, Rumpler Y. A molecular phylogeny of living primates. PLoS Genet. 2011;7(3):e1001342. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams BA, Kay RF, Kirk EC. New perspectives on anthropoid origins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(11):4797–4804. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908320107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takai M, Anaya F, Shigehara N, Setoguchi T. New fossil materials of the earliest new world monkey, Branisella boliviana, and the problem of platyrrhine origins. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2000;111(2):263–281. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(200002)111:2<263::AID-AJPA10>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleagle JG. Primate Adaptation and Evolution. 2. Waltham: Academic Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Schrago CG. On the time scale of new world primate diversification. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2007;132(3):344–354. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.20459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgson JA, Sterner KN, Matthews LJ, Burrell AS, Jani RA, Raaum RL, Stewart CB, Disotell TR. Successive radiations, not stasis, in the South American primate fauna. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(14):5534–5539. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810346106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay RF, Fleagle JG, Mitchell TR, Colbert M, Bown T, Powers DW. The anatomy of Dolichocebus gaimanensis, a stem platyrrhine monkey from Argentina. J Hum Evol. 2008;54(3):323–382. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vucetich MG, Vieytes EC MEP, Carlini AA. In: The Paleontology of Gran Barranca Evolution and Environmental Change through the Middle Cenozoic of Patagonia. Madden RH, Carlini AA, Vucetich MG, Kay RF, editor. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2010. The rodents from La Cantera; pp. 193–205. [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand OC, Flynn JJ, Croft DA, Wyss AR. Two New Taxa (Caviomorpha, Rodentia) from the Early Oligocene Tinguiririca Fauna (Chile) Am Mus Novit. 2012;3750:1–36. doi: 10.1206/3750.2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. Clustal-W - Improving the Sensitivity of Progressive Multiple Sequence Alignment through Sequence Weighting, Position-Specific Gap Penalties and Weight Matrix Choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22(22):4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP. MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2003;19(12):1572–1574. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pond SLK, Frost SDW, Muse SV. HyPhy: hypothesis testing using phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(5):676–679. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang ZH. PAML 4: Phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24(8):1586–1591. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- dos Reis M, Yang ZH. Approximate Likelihood Calculation on a Phylogeny for Bayesian Estimation of Divergence Times. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28(7):2161–2172. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rannala B, Yang ZH. Inferring speciation times under an episodic molecular clock. Syst Biol. 2007;56(3):453–466. doi: 10.1080/10635150701420643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelman A, Rubin DB. Inference from iterative simulation using multiple sequences. Stat Sci. 1992;7:457–511. doi: 10.1214/ss/1177011136. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li CK, Ting SY. The paleogene mammals of china. Bull Carnagie Mus Nat His. 1983;21:1–93. [Google Scholar]

- Benton MJ, Donoghue PC. Paleontological evidence to date the tree of life. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24(1):26–53. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tassy P, Pickford M. Un nouveau mastodonte zygolophodonte (proboscidea, mammalia) dans le mioccne inférieur d’afrique orientale. Geobios. 1983;16(1):53–77. doi: 10.1016/S0016-6995(83)80047-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seiffert ER, Simons EL, Clyde WC, Rossie JB, Attia Y, Bown TM, Chatrath P, Mathison ME. Basal anthropoids from Egypt and the antiquity of Africa's higher primate radiation. Science. 2005;310(5746):300–304. doi: 10.1126/science.1116569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose KD, DeLeon VB, Missiaen P, Rana RS, Sahni A, Singh L, Smith T. Early Eocene lagomorph (Mammalia) from Western India and the early diversification of Lagomorpha. Proc R Soc B. 2008;275(1639):1203–1208. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2007.1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng J, Hu YM, Li CK. The osteology of Rhombomylus (mammalia, glires): Implications for phylogeny and evolution of glires. Bull Am Mus Nat Hist. 2003;275:1–247. [Google Scholar]

- Marivaux L, Vianey-Liaud M, Jaeger JJ. High-level phylogeny of early Tertiary rodents: dental evidence. Zool J Linn Soc. 2004;142(1):105–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-3642.2004.00131.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shevyreva NS. Flora i Fauna Zaysanskoi Vpadiny. Tblisi: Akademiya Nauk Gruzinskoy SSR; 1984. New early Eocene rodents from the Zaysan Basin; pp. 77–114. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs L, Flynn L. Interpreting the Past: Essays on Human, Primate, and Mammal Evolution in Honor of David Pilbeam. Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers; 2005. Of mice … again: the Siwalik rodent record, murine distribution, and molecular clocks; pp. 63–80. [Google Scholar]