Abstract

Objective

To determine the effects of pain and opioid pain medication use on clinical and functional outcomes in 1004 primary care patients with an anxiety disorder randomized to receive the CALM collaborative care intervention (CBT and/or medication) versus usual care.

Methods

1004 patients with PD, GAD, SAD, or PTSD were randomized to CALM or usual care. Outcomes at 6, 12, and 18 months were compared in patients with and without moderate pain interference (for the entire anxiety disorder group and then just those with comorbid major depression) and in patients taking and not taking opioid medication (entire group, just those with comorbid major depression, and just those with moderate pain interference).

Results

Patients with pain interference and patients taking opioid pain medication were more anxious (BSI anxiety subscale) and disabled (Sheehan Disability) at baseline, improved over time at similar rates, but at 18 months had lower response and remission rates. There was no moderating effect on the intervention. In patients with comorbid major depression, patients using opioid medications showed a trend for less disability improvement over time, and in patients with pain, patients using opioids showed less sustained anxiety response at 18 months.

Conclusions

Anxious patients with pain benefit as much as those without pain from CBT and medication treatment. Among patients with pain, however, there is some evidence of a reduced anxiety treatment response in those taking opioid medication, which should be further studied.

Keywords: pain, prescription opioid use, anxiety, depression, primary care, randomized controlled trial

INTRODUCTION

Pain problems that prompt medical care seeking or disability occur commonly in individuals with depressive (1) and anxiety (2) disorders. Several controlled observational analyses have shown that pain complaints predict poorer outcome for patients receiving treatment for depression (3–5), but ability to determine differential effects on treatment outcome (a prescriptive or moderator rather than predictive effect (6)) is limited without a placebo or usual care comparator. Despite this extensively documented association between pain and depression, only five randomized controlled trials (7–11) have examined the moderating effect of pain complaints on dichotomous treatment outcomes (i.e., response or remission) in depression or anxiety.

Two studies examined the effects of pain on depression outcomes after treatment with duloxetine or placebo. One study showed comparable effects of duloxetine in patients with and without pain (8), while the second showed that patients with pain had a better response to duloxetine than patients without pain (7). Two studies examined the effects of pain on depression outcomes with a usual care control condition. Whereas one study found that pain selectively predicted poorer intervention outcome in a collaborative care study of geriatric depression (11), the second study found that pain predicted worse outcome in both intervention and usual care conditions (9). A recent study examined the effects of pain on anxiety outcomes in a collaborative care treatment study and also found worse anxiety outcomes in those anxious patients reporting higher pain, regardless of whether they were in the intervention or usual care condition (10). That study also examined continuous symptom changes over time and found that those with higher pain receiving the intervention had greater relative improvement than the usual care group, though this improvement was insufficient for them to “catch up” and achieve equivalent rates of response or remission.

Even fewer studies have focused on the impact of pain medications on depressive and anxiety outcomes. Over the past decade, there has been a great increase in the use of prescription opioid medications for non-cancer related pain conditions (12). A number of studies have shown that use of prescription opioid medications is more common in patients with depression and anxiety disorders than in patients without these conditions (13, 14). Thus, patients with pain complaints and depression or anxiety are more likely to be taking prescription opioids. Small studies in selected populations have suggested that methadone, buprenorphine, tramadol, morphine, and other opioids may be effective for the treatment of anxiety and depression (15), but the impact of concurrent opioid treatment has not been established.

In this report, we examine the predictive and prescriptive effects of pain interference and use of prescription opioid medication at baseline, on anxiety symptoms and related disability outcomes in 1004 patients with one of four anxiety disorders participating in a multisite randomized controlled trial of collaborative care (the Coordinated Anxiety Learning and Management (CALM) study) (16). We hypothesized that pain and use of prescription opioid medication would predict worse outcomes, but that there would be no moderating effect of either variable on the intervention. We also performed secondary analyses in the large subgroup of anxious patients who had comorbid major depression, using depression rather than anxiety as an outcome. Finally, to elucidate the role of prescription opioid use only in those anxious patients with pain interference (i.e., those patients potentially in need of pain medication), we repeated analyses in this subgroup only, comparing anxiety and disability outcomes in those using and not using prescription opioids.

METHODS

Setting, Subjects, and Design

Between June 2006 and April 2008, 1004 primary care patients, 18–75 years old, receiving care at one of 17 clinics in Little Rock, Los Angeles County, San Diego, and Seattle, and meeting DSM-IV criteria for panic disorder (PD), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), social anxiety disorder (SAD), and/or posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) were enrolled in the CALM study. Primary care providers and clinic nursing staff referred all potential subjects, facilitated by an optional five question anxiety screener (17). To determine eligibility, referred subjects were administered the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (18) by a specially trained master’s level (social work, nursing, or psychologist) clinician, the Anxiety Clinical Specialist (ACS).

Co-occurring major depression was permitted. Persons unlikely to benefit from CALM (i.e., persons with unstable medical conditions, marked cognitive impairment, active suicidal intent or plan, psychosis, bipolar I disorder, substance abuse or dependence except for alcohol and marijuana abuse) were excluded. All subjects gave informed, written consent for the study, which was approved by each institution’s Institutional Review Board. After a baseline interview (see below) subjects were randomized to CALM or usual care (UC) for one year, using an automated computer program at RAND, where all post-eligibility assessments were conducted by phone.

Intervention (CALM)/Usual Care (UC)

CALM used a web-based monitoring system (19) modeled on the IMPACT intervention (20) with newly developed anxiety content, and a computer-assisted cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) program that guided the patient and clinician (21). CALM patients initially received their preferred course of treatment, either medication, CBT, or both, over 10 to 12 weeks. CBT was administered by the ACS (typically in 6 to 8 weekly sessions), while medication was prescribed by the primary care physician. A local study psychiatrist provided single session medication management training to providers using a simple algorithm (22), as needed consultation by phone or e-mail, and very rarely, a face to face assessment for complex or treatment refractory patients.

The ACS tracked patient outcomes on a Web-based system by entering scores for the Overall Anxiety Severity and Impairment Scale (OASIS) (23) and a 3-item version of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), and examining graphical progress over time. The goal was either clinical remission, defined as an OASIS < 5 = “mild”, sufficient improvement such that the patient did not want further treatment, or improvement with residual symptoms or other emergent problems requiring a non-protocol psychotherapy (i.e., dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), family or dynamic psychotherapy). Symptomatic patients thought to benefit from additional treatment with CBT or medication could receive more of the same modality (“stepping up”) or the alternative modality (“stepping over”), over the next 9 months. After treatment completion, patients were entered into “continued care” and received monthly follow-up phone calls to reinforce CBT skills and/or medication adherence for the remainder of the year. All ACSs received weekly supervision from a psychiatrist and psychologist. Of 503 patients randomized to CALM, 482 received treatment; 166 (34%) had only CBT visits; 43 (9%) had only medication visits; and 273 (57%) had both. The majority (424 or 88%) had all visits completed by 6 months.

UC patients continued to be treated by their physician in the usual manner, i.e., with medication, counseling (7 of 17 clinics had limited in-clinic mental health resources, usually a single provider with limited familiarity with evidence-based psychotherapy (24)) or referral to a mental health specialist. After the eligibility diagnostic interview, the only contact UC patients had with study personnel was for assessment by phone.

Assessments

The assessment battery was administered at baseline, 6, 12, and 18 months via centralized phone survey by the RAND Survey Research Group who were blinded to treatment assignment. The primary outcome was a generic measure of two key components of all anxiety disorders, psychic and somatic anxiety: the Brief Symptom Inventory 12-item subscale for anxiety and somatization (BSI-12) (25). Response was defined as a ≥ 50% reduction on the BSI-12, or meeting the definition of remission, and remission was defined as a face-valid per item score of < 0.5 (between “none” and “mild”, total BSI-12 score < 6), consistent with previous analyses using the BSI for depression outcomes (26). Secondary measures included depression (8-item version of the PHQ-9 (27)) and functional status (Sheehan Disability (28) and SF-12 (29)). The single pain item on the SF-12 was used to determine baseline pain status, as previously described (9, 11). Patients were dichotomized into those with no or limited pain interference (“not at all” or “a little bit”) versus those with pain interference (“moderate”, “quite a bit”, or “a lot”). Self reported use of medication at baseline was obtained by telephone survey interviewers who requested that patients get their pill bottles and read the names of each medication they were taking. It was used to dichotomize patients into those taking prescription opioid medication versus those not taking prescription opioid medication.

Analysis

We compared demographics and baseline anxiety and depression disorder and symptom rates by pain and opioid medication group using t-tests and chi-square tests for continuous and categorical variables respectively. To estimate the effect of baseline pain status or opioid medication status over time we jointly modeled the outcomes at the four assessment times (baseline and 3 follow-ups at 6, 12, and 18 months) by intervention status, time, pain or opioid subgroup (controlling for the other subgroup), and the interaction of intervention, time and pain or opioid subgroup, and site. In models where the 3-way interaction was non-significant, we refit the model including 2-way interactions of pain or opioid subgroup with wave and intervention with wave, dropping the 3-way interactions. Time was treated as a categorical variable. To avoid restrictive assumptions, the covariance of the outcomes at the four assessment times was left unstructured. We fitted the proposed model using a restricted maximum likelihood approach, which produces valid estimates under the missing-at-random assumption (30). This approach correctly handles the additional uncertainty arising from missing data and uses all available data to obtain unbiased estimates for model parameters (31). This is an efficient way for conducting an intent-to-treat analysis since it includes all the subjects with a baseline assessment. Our principal analysis focused on the entire sample and two outcomes: BSI-12 anxiety score and Sheehan Disability score. Also, we repeated these analyses for the subgroup of patients who met criteria for major depression, using PHQ-8 and Sheehan Disability scores as outcomes. Finally, to clarify the role of prescription opioid use in those with pain interference, we performed analyses on the subgroup of patients with high pain interference, and examined the effects of prescription opioid use vs. no use in this cohort. For cross-sectional analyses, we used attrition weights to correctly account for participants who missed one or more follow-up assessments. The statistical software used was SAS version 9 (SAS Institute Inc., North Carolina). All p values were 2-tailed and we adopted a conservative significance level of p < .01 to account for multiple comparisons. P values between 0.05 and 0.01 are interpreted as hypothesis generating and heuristic, rather than definitive.

RESULTS

There were 45% (441 of 1004) of patients endorsing at least moderate pain interference and 8.5% (86 of the 1004) of patients taking prescription opioid medication at baseline. Patients with moderate pain interference, compared to those with mild or no pain interference, were older and more medically ill, were less educated and less likely to be privately insured, and more likely to be female, African American, and to have PTSD and comorbid depression (Table 1). The findings were somewhat similar when comparing the smaller group of patients taking opioid medication in the prior six months to those not taking opioid medication, except that there were no gender, education, or ethnicity effects (Table 2). Patients endorsing pain interference were significantly more likely to be taking prescription opioid medication than those without pain interference (16% vs. 2%) and patients taking opioid medication were significantly more likely to endorse at least moderate pain interference (83% vs. 40%).

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients with Moderate Pain Interference vs. Patients with Mild or No Pain Interferencea

| All (n = 1004) |

Moderate Pain Interference (n = 441) |

Mild or No Pain Interference (n = 563) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y* | 43.47 (13.44) | 46.69 (13.13) | 40.96 (13.16) |

| Women* | 714 (71) | 340 (77) | 374 (66) |

| Education | |||

| < High school* | 55 (5) | 39 (9) | 16 (3) |

| 12 y | 165 (16) | 76 (17) | 89 (16) |

| > 12 y | 782 (78) | 325 (74) | 457 (81) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic | 196 (20) | 88 (20) | 108 (19) |

| African American* | 116 (12) | 66 (15) | 50 (9) |

| White | 568 (57) | 228 (52) | 340 (60) |

| Other | 124 (12) | 59 (13) | 65 (12) |

| No. of chronic medical conditions | |||

| 0 | 202 (20) | 47 (11) | 155 (28) |

| 1 | 219 (22) | 64 (15) | 155 (28) |

| ≥ 2* | 582 (58) | 330 (75) | 252 (45) |

| Anxiety disorderc | |||

| Panic | 475 (47) | 224 (51) | 251 (45) |

| Generalized anxiety | 756 (75) | 335 (76) | 421 (75) |

| Social phobia | 405 (40) | 173 (39) | 232 (41) |

| Posttraumatic stress* | 181 (18) | 118 (27) | 63 (11) |

| Major depressive disorder* | 648 (65) | 348 (79) | 300 (53) |

| Type of health insurancec | |||

| Medicaid* | 101 (10) | 65 (15) | 36 (6) |

| Medicare* | 124 (12) | 81 (18) | 43 (8) |

| Other government insuranced | 35 (3) | 17 (4) | 18 (3) |

| Private insurance* | 749 (75) | 302 (69) | 447 (80) |

| No insurance | 141 (14) | 66 (15) | 75 (13) |

| Any opioid medication* | 86 (9) | 71 (16) | 15 (3) |

| Intervention | 503 (50) | 216 (49) | 287 (51) |

SD = standard deviation.

Data are reported as No. (%) unless otherwise indicated. Percentages may not total 100 due to rounding.

Because patients could have more than one, Ns may total more than 1004.

Includes Veterans’ Administration benefits, TRICARE, county programs, or other government insurance not otherwise specified.

p < .05 by t test or chi-square.

TABLE 2.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients Taking Opioid Medication Prior to the Six-Month Evaluation vs. Patients Not Taking Opioid Medicationa

| All (n = 1004) |

Any Baseline Opioids (n = 86) |

No Baseline Opioids (n = 918) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y* | 43.47 (13.44) | 49.95 (11.26) | 42.87 (13.48) |

| Women | 714 (71) | 62 (72) | 652 (71) |

| Education | |||

| < High school | 55 (5) | 9 (10) | 46 (5) |

| 12 y | 165 (16) | 15 (17) | 150 (16) |

| > 12 y | 782 (78) | 62 (72) | 720 (79) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic | 196 (20) | 13 (15) | 183 (20) |

| African American | 116 (12) | 12 (14) | 104 (11) |

| White | 568 (57) | 50 (58) | 518 (56) |

| Other | 124 (12) | 11 (13) | 113 (12) |

| No. of chronic medical conditions | |||

| 0 | 202 (20) | 3 (3) | 199 (22) |

| 1 | 219 (22) | 5 (6) | 214 (23) |

| ≥ 2* | 582 (58) | 78 (91) | 504 (55) |

| Anxiety disorderc | |||

| Panic | 475 (47) | 39 (45) | 436 (48) |

| Generalized anxiety | 756 (75) | 65 (76) | 691 (75) |

| Social phobia | 405 (40) | 38 (44) | 367 (40) |

| Posttraumatic stress* | 181 (18) | 23 (27) | 158 (17) |

| Major depressive disorder* | 648 (65) | 73 (85) | 575 (63) |

| Type of health insurancec | |||

| Medicaid* | 101 (10) | 25 (29) | 76 (8) |

| Medicare* | 124 (12) | 28 (33) | 96 (10) |

| Other government insuranced | 35 (3) | 6 (7) | 29 (3) |

| Private insurance* | 749 (75) | 52 (60) | 697 (76) |

| No insurance | 141 (14) | 6 (7) | 135 (15) |

| Any pain interference from SF-12* | 441 (44) | 71 (83) | 370 (40) |

| Intervention | 503 (50) | 46 (53) | 457 (50) |

SD = standard deviation; SF-12 = 12-item Short Form Health Survey.

Data are reported as No. (%) unless otherwise indicated. Percentages may not total 100 due to rounding.

Because patients could have more than one, Ns may total more than 1004.

Includes Veterans’ Administration benefits, TRICARE, county programs, or other government insurance not otherwise specified.

p < .05 by t test or chi-square.

Wald tests for 3-way interactions in each of the models were non-significant. Patients with baseline pain interference had higher anxiety scores (t = 11.58, p < .001) and greater disability (t = 7.77, p < .001) at baseline. Over the 18-month study, patients with baseline pain interference tended to show greater decreases in anxiety than those without baseline pain interference at all three follow-up waves (Wald F = 3.77, df = 990, p = .0105), controlling for baseline opioid status (Figure 1). They did not show differences in decreases in disability (Wald F = 0.84, df = 990, p = .47).

FIGURE 1.

BSI-12 scores over time for those with and without moderate pain at baseline. BSI-12 indicates Brief Symptom Inventory 12-item anxiety subscale.

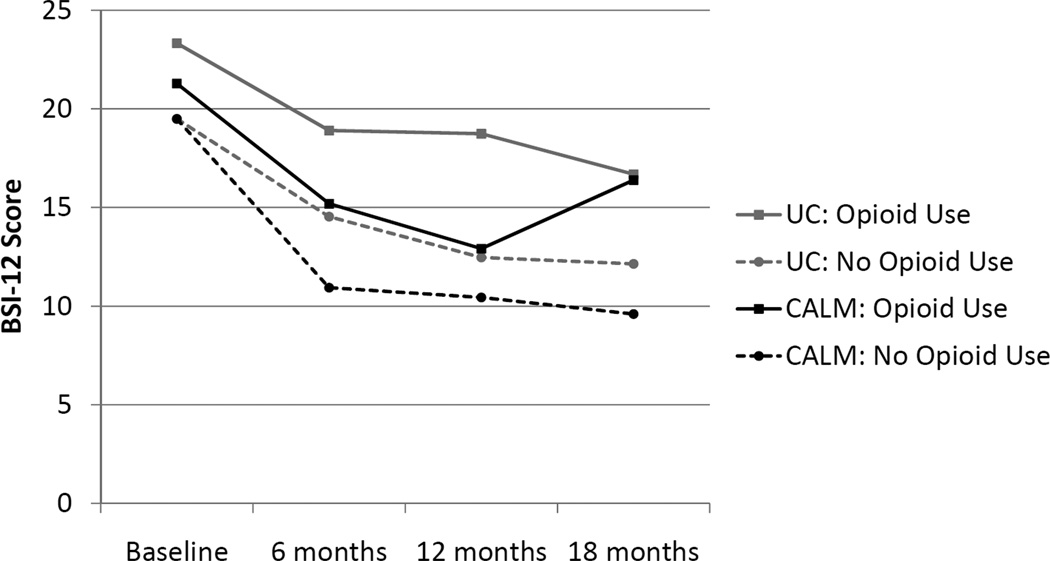

Patients taking prescription opioid medication had higher anxiety scores (t = 3.43, p < .001) and greater disability (t = 2.21, p = .028) at baseline. Over the 18-month study, decreases in anxiety symptoms (Wald F = 0.84, df = 990, p = .47) (Figure 2) and disability (Wald F = 1.23, df = 990, p = .29) were no different in this subgroup compared to patients not taking prescription opioid medication.

FIGURE 2.

BSI-12 scores over time for those with and without baseline use of opioids. BSI-12 indicates Brief Symptom Inventory 12-item anxiety subscale.

In contrast to the above analyses of continuous scores, categorical analyses comparing patients with pain interference to those without pain interference showed significantly lower response and remission rates at all three outcome windows (6, 12, and 18 months) (Table 3). The results were less consistent when patients taking opioid medication were compared to those not taking opioid medication. Response rates for patients taking opioid medications were significantly lower at only two time points, and remission rates were only lower at the 12-month time point (Table 4). There was no significant interaction (p < .01) with intervention received.

TABLE 3.

Proportion with and without Moderate Pain Interference Achieving Response and Remission from Baseline BSI-12 Scorea

| Responseb | Moderate Pain Interference % (CI) |

Mild or No Pain Interference % (CI) |

p |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6 months | 0.40 (0.35–0.45) | 0.52 (0.48–0.57) | < .001 |

| 12 months | 0.49 (0.43–0.54) | 0.59 (0.54–0.64) | < .009 |

| 18 months | 0.52 (0.46–0.57) | 0.64 (0.59–0.69) | < .002 |

| Remissionc | % (CI) | % (CI) | p |

| 6 months | 0.22 (0.18–0.26) | 0.45 (0.40–0.50) | < .001 |

| 12 months | 0.31 (0.26–0.36) | 0.50 (0.45–0.55) | < .001 |

| 18 months | 0.31 (0.26–0.37) | 0.53 (0.48–0.58) | < .001 |

BSI-12 = Brief Symptom Inventory 12-item anxiety subscale; CI = confidence interval.

Data presented as proportion (percentage) weighted for non-response at each follow-up, CI in parentheses.

Response defined as ≥ 50% reduction on the BSI-12, with all those in remission considered to have responded.

Remission defined as a per item BSI-12 score of < 0.5 (total score < 6).

TABLE 4.

Proportion Taking and Not Taking Prescribed Opioids Achieving Response and Remission from Baseline BSI-12 Scorea

| Responseb | Opioid Medication % (CI) |

No Opioid Medication % (CI) |

p |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6 months | 0.30 (0.20–0.43) | 0.49 (0.45–0.52) | < .006 |

| 12 months | 0.42 (0.30–0.55) | 0.56 (0.52–0.60) | < .044 |

| 18 months | 0.47 (0.34–0.60) | 0.60 (0.56–0.63) | < .001 |

| Remissionc | % (CI) | % (CI) | p |

| 6 months | 0.26 (0.16–0.39) | 0.34 (0.31–0.38) | NS |

| 12 months | 0.23 (0.14–0.36)) | 0.43 (0.39–0.47) | < .007 |

| 18 months | 0.29 (0.18–0.42) | 0.45 (0.41–0.49) | < .03 |

BSI-12 = Brief Symptom Inventory 12-item anxiety subscale; CI = confidence interval.

Data presented as proportion (percentage) weighted for non-response at each follow-up, CI in parenthesis.

Response defined as ≥ 50% reduction on the BSI-12, with all those in remission considered to have responded.

Remission defined as a per item BSI-12 score of < 0.5 (total score < 6).

We repeated the above analyses for the subgroup of patients with major depression, using PHQ-8 as the outcome measure. In these analyses, Wald tests for 3-way interactions were non-significant. In patients with major depression, the group with pain interference at baseline had higher PHQ-8 (T = 5.71, p < .001) and Sheehan Disability scores (T = 5.53, p < .001) at baseline that remained worse at each of the subsequent time points. When patients with major depression were divided according to those taking and not taking prescription opioids at baseline, the results were similar for PHQ-8 outcomes (prescription opioid users at baseline were more depressed at baseline (t = 3.16, p = .002) and remained more depressed over time). In contrast, for Sheehan Disability, patients taking prescription opioids at baseline (who had comparable disability scores to those not taking prescription opioids) showed a trend for less disability improvement over time (Wald F = 2.80, df = 634, p = .039) than those not taking prescription opioids (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Sheehan Disability scores over time for depressed patients, with and without baseline use of opioids.

Finally, we examined separately the subgroup of patients with pain interference and compared outcomes in those taking (n = 71) and not taking (n = 370) opioid medications. The 3-way interaction effect for use of prescription opioids on Sheehan Disability over time was not significant, but there was a trend for 3-way interaction for BSI-12 anxiety (Wald F = 2.61, df = 427, p = .051). The intervention seemed to lose its beneficial effect at 18 months in those using prescription opioids (Figure 4). These last analyses should be seen as exploratory given the smaller sample size and the small number of patients taking opioid medications.

FIGURE 4.

BSI-12 scores over time in patients with moderate pain at baseline, with and without baseline use of opioids. BSI-12 indicates Brief Symptom Inventory 12-item anxiety subscale; CALM, Coordinated Anxiety Learning and Management group; UC, usual care group.

DISCUSSION

These findings show that patients with pain interference at baseline and patients taking prescription opioid medication at baseline are more severely ill, reporting higher anxiety, depression, and disability scores. Although the groups did not respond differently to treatment on continuous measures of anxiety, patients with pain interference (compared to those without pain interference) and those taking prescription opioid medication (compared to those not taking opioid medication) were less likely to respond (i.e., show a 50% decrease in their BSI anxiety score) or remit (i.e., less than 6 on their BSI anxiety score). Thus, even though the average decrease in anxiety symptoms over time was somewhat greater in patients with pain disability at baseline, it was not sufficient to "catch up" to produce equivalent response or remission rates at either 6, 12, or 18 months. The comparison of response and remission rates in patients taking opioid vs. those not taking opioids produced less consistent results, possibly because the sample size had reduced power to detect effects of interest, or because baseline users may not have continued use while other baseline non-users may have begun use. Specifically, response rate differences only occurred at 6 and 18 months and remission rate differences only occurred at 12 months. These categorical analyses cannot control for baseline differences on the BSI anxiety subscale score used to compute these categorical measures.

There was no evidence that the CALM collaborative care intervention was more or less effective in patients with baseline pain interference or in patients taking prescription opioid medication. Thus, neither pain nor opioid medication use appeared to selectively moderate the effect of the intervention, consistent with our hypothesis. These findings are consistent with the notion that these two subgroupings are not mutually exclusive and constitute two different ways to measure distress and disability resulting from pain. Opioid use may be a marker for more severe pain or other disabling medical comorbidity.

Secondary analyses revealed some interesting findings regarding the potential adverse effects of use of prescription opioid medication on anxiety outcome. This potential effect is much more circumscribed than the broader set of adverse clinical effects recently shown to be present in returning veterans with opioid use that is more extensive in duration, dose and potency(32). This question was not an a priori focus of the CALM study and so the findings must be viewed as tentative. In the subgroup of patients with major depression, those taking prescription opioid medication showed a borderline significant trend for less disability improvement over time, compared to those not taking prescription opioids at baseline. Although this finding fell short statistically (by failing to meet p < .01), it suggests that chronic prescription opioid medication might be associated with worse depression outcomes. Interestingly, negative effects like anxiety and depression appear to predict worse opioid effects on pain(33). Finally, when we examined the effect of opioid medication use on outcomes in patients reporting high pain interference, the beneficial effect of the intervention on symptoms of anxiety, which was clearly evident at the 6 and 12 month time points (during which treatment was still active) was not sustained at 18 months (6 months after treatment had ceased). These latter data point to the possibility of an association between prescription opioid use and less than optimal effectiveness of mental health treatment, but more data are required to confirm this association. However, while self-reports of medication use are reasonably valid(34), self-reports of opioid use are less often validated than reports of other medication use(35), and use in many of these subjects may have been intermittent and not consistent over the 18 month course of the study. Thus this 18 month finding must be viewed as very tentative.

An important clinical question is the degree to which treating pain improves (or impedes) patients’ responsiveness to psychological treatments. It is important to note that our measure of pain is a single self report item that was not validated by other more objective observations. Nonetheless, we did not find evidence that prescription opioid treatment improves response to anxiety treatment; in fact, the results suggested either a neutral or deleterious effect. This is relevant to clinical care because patients with pain often attribute their anxiety and depression to their pain problem: “If you treat my pain, my anxiety/depression will get better.” Rather, our data suggest that opioid treatment may retard responsiveness to anxiety treatment or make it less enduring. These findings were marginally significant and found only in subsets of the CALM treatment population. Thus, they need to be replicated in a larger study that examines this question specifically. Also, conceivably, patients receiving prescription opioids for their pain may have had more severe pain and/or other medical factors that contributed to their poorer outcomes.

In summary, in a large, primary care sample of patients with anxiety disorders, while comorbid pain interference does not necessarily impede response to treatment, it is associated with reduced likelihood of achieving response or remission with treatment. Also, prescription opioid use among those with pain interference, and possibly those with comorbid major depression, is unlikely to improve – and may even retard – response to treatment, though this hypothesis needs to be further explored in subsequent controlled studies.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This work was supported in part by the National Institute of Mental Health (Grants U01 MH057858 and K24 MH065324 to Dr. Roy-Byrne; Grant U01 MH070018 to Dr. Sherbourne; Grant U01 MH058915 to Dr. Craske; Grant U01 MH070022 to Dr. G. Sullivan; and Grants U01MH057835 and K24 MH64122 to Dr. Stein) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (Grant R01 DA022560 to Dr. M. Sullivan). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health or the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Potential Conflicts of Interest: Dr. Roy-Byrne reports income from editorial work on the evidence-based physician resource, UpToDate, on the journal Depression and Anxiety, and on Journal Watch Psychiatry, and stock options from his consulting work with the electronic medical record company, Valant Medical Solutions. Dr. Sullivan reports receiving grants from Pfizer and Covidien, and having served on a Janssen advisory board. Dr. Craske reports receiving royalties from Oxford University Press and APA Books. Dr. Stein reports income from editorial work on the evidence-based physician resource, UpToDate, and on the journal Depression and Anxiety. For the remaining authors none were declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Von Korff M, Simon G. The relationship between pain and depression. The British journal of psychiatry. 1996:101–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sareen J, Cox BJ, Clara I, Asmundson GJ. The relationship between anxiety disorders and physical disorders in the U.S. National Comorbidity Survey. Depression and anxiety. 2005;21:193–202. doi: 10.1002/da.20072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bair MJ, Robinson RL, Eckert GJ, Stang PE, Croghan TW, Kroenke K. Impact of pain on depression treatment response in primary care. Psychosomatic medicine. 2004;66:17–22. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000106883.94059.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karp JF, Scott J, Houck P, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Kupfer DJ, Frank E. Pain predicts longer time to remission during treatment of recurrent depression. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 2005;66:591–597. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karp JF, Weiner D, Seligman K, Butters M, Miller M, Frank E, Stack J, Mulsant BH, Pollock B, Dew MA, Kupfer DJ, Reynolds CF., 3rd Body pain and treatment response in late-life depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13:188–194. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.3.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fournier JC, DeRubeis RJ, Shelton RC, Hollon SD, Amsterdam JD, Gallop R. Prediction of response to medication and cognitive therapy in the treatment of moderate to severe depression. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2009;77:775–787. doi: 10.1037/a0015401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fava M, Wiltse C, Walker D, Brecht S, Chen A, Perahia D. Predictors of relapse in a study of duloxetine treatment in patients with major depressive disorder. Journal of affective disorders. 2009;113:263–271. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wohlreich MM, Sullivan MD, Mallinckrodt CH, Chappell AS, Oakes TM, Watkin JG, Raskin J. Duloxetine for the treatment of recurrent major depressive disorder in elderly patients: treatment outcomes in patients with comorbid arthritis. Psychosomatics. 2009;50:402–412. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.50.4.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kroenke K, Shen J, Oxman TE, Williams JW, Jr., Dietrich AJ. Impact of pain on the outcomes of depression treatment: results from the RESPECT trial. Pain. 2008;134:209–215. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Teh CF, Morone NE, Karp JF, Belnap BH, Zhu F, Weiner DK, Rollman BL. Pain interference impacts response to treatment for anxiety disorders. Depression and anxiety. 2009;26:222–228. doi: 10.1002/da.20514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thielke SM, Fan MY, Sullivan M, Unutzer J. Pain limits the effectiveness of collaborative care for depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15:699–707. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3180325a2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Braden JB, Fan MY, Edlund MJ, Martin BC, DeVries A, Sullivan MD. Trends in use of opioids by noncancer pain type 2000–2005 among Arkansas Medicaid and HealthCore enrollees: results from the TROUP study. J Pain. 2008;9:1026–1035. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sullivan MD, Edlund MJ, Zhang L, Unutzer J, Wells KB. Association between mental health disorders, problem drug use, and regular prescription opioid use. Archives of internal medicine. 2006;166:2087–2093. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.19.2087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edlund MJ, Martin BC, Fan MY, Braden JB, Devries A, Sullivan MD. An analysis of heavy utilizers of opioids for chronic noncancer pain in the TROUP study. Journal of pain and symptom management. 2010;40:279–289. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tenore PL. Psychotherapeutic benefits of opioid agonist therapy. Journal of addictive diseases. 2008;27:49–65. doi: 10.1080/10550880802122646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roy-Byrne P, Craske MG, Sullivan G, Rose RD, Edlund MJ, Lang AJ, Bystritsky A, Welch SS, Chavira DA, Golinelli D, Campbell-Sills L, Sherbourne CD, Stein MB. Delivery of evidence-based treatment for multiple anxiety disorders in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;303:1921–1928. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Means-Christensen A, CD S, Roy-Byrne P, MG C, MB S. Using five questions to screen for five common mental disorders in primary care: the anxiety and depression detector (ADD) General hospital psychiatry. 2006;28:108–118. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, Hergueta T, Baker R, Dunbar GC. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview for DSM-IV adn ICD-10. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1998;59(supp):22–33. quiz 4–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Unutzer J, Choi Y, Cook IA, Oishi S. A web-based data management system to improve care for depression in a multicenter clinical trial. Psyc Services. 2002;53:671–673. 678. doi: 10.1176/ps.53.6.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Unutzer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, Williams JWJ, Hunkeler E, Harpole L, Hoffing M, Della Penna RD, Noel PH, Lin EHB, Arean PA, Hegel MT, Tang L, Belin TR, Oishi S, Langston C. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting. JAMA. 2002;288:2836–2845. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.22.2836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Craske MG, Rose RD, Lang A, Welch SS, Campbell-Sills L, Sullivan G, Sherbourne C, Bystritsky A, Stein MB, Roy-Byrne PP. Computer-assisted delivery of cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders in primary-care settings. Depression and anxiety. 2009;26:235–242. doi: 10.1002/da.20542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roy-Byrne P, Veitengruber JP, Bystritsky A, Edlund MJ, Sullivan G, Craske MG, Welch SS, Rose R, Stein MB. Brief intervention for anxiety in primary care patients. J Am Board Fam Med. 2009;22:175–186. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2009.02.080078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Campbell-Sills L, Norman SB, Craske MG, Sullivan G, Lang AJ, Chavira DA, Bystritsky A, Sherbourne C, Roy-Byrne P, Stein MB. Validation of a brief measure of anxiety-related severity and impairment: the Overall Anxiety Severity and Impairment Scale (OASIS) Journal of affective disorders. 2009;112:92–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weissman MM, Verdeli H, Gameroff MJ, Bledsoe SE, Betts K, Mufson L, Fitterling H, Wickramaratne P. National survey of psychotherapy training in psychiatry, psychology, and social work. Archives of general psychiatry. 2006;63:925–934. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.8.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Derogatis L. BSI-18: Brief Symptom Inventory 18 administration, scoring, and procedures manual. Minneapolis: NCS Pearson, Inc; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simon GE, Katon WJ, VonKorff M, Unutzer J, Lin EH, Walker EA, Bush T, Rutter C, Ludman E. Cost-effectiveness of a collaborative care program for primary care patients with persistent depression. The American journal of psychiatry. 2001;158:1638–1644. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.10.1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sheehan DV, Harnett-Sheehan K, Raj BA. The measurement of disability. International clinical psychopharmacology. 1996;11(Suppl 3):89–95. doi: 10.1097/00004850-199606003-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ware JE, Jr., Kosinski M, Bowker D, Gandek B. How to Score Version 2 of the SF-12 health survey (with a Supplement Documenting Version 1) Lincoln, RI: Quality Metric Incorporated; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Littell RC, Milliken GA, Stroup WW, Wolfinger RD. SAS System for Mixed Models. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Little R, Rubin D. Statistical analysis with missing data. New York: Joh Wiley and Sons; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seal KH, Shi Y, Cohen G, Cohen BE, Maguen S, Krebs EE, Neylan TC. Association of mental health disorders with prescription opioids and high-risk opioid use in US veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan. JAMA. 307:940–947. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jamison RN, Edwards RR, Liu X, Ross EL, Michna E, Warnick M, Wasan AD. Relationship of Negative Affect and Outcome of an Opioid Therapy Trial Among Low Back Pain Patients. Pain Pract. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2012.00575.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Glintborg B, Hillestrom PR, Olsen LH, Dalhoff KP, Poulsen HE. Are patients reliable when self-reporting medication use? Validation of structured drug interviews and home visits by drug analysis and prescription data in acutely hospitalized patients. Journal of clinical pharmacology. 2007;47:1440–1449. doi: 10.1177/0091270007307243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sarangarm P, Young B, Rayburn W, Jaiswal P, Dodd M, Phelan S, Bakhireva L. Agreement between self-report and prescription data in medical records for pregnant women. Birth defects research. 2012;94:153–161. doi: 10.1002/bdra.22888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]