Abstract

This research examined optimism’s relationship with total cholesterol, high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, and triglycerides. The hypothesis that optimism is associated with a healthier lipid profile was tested. Participants were 990 mostly white men and women from the Midlife in the United States study who were on average 55.1 years old. Optimism was assessed by self-report with the Life Orientation Test. A fasting blood sample was used to assess serum lipid levels. Linear and logistic regression models examined the cross-sectional association between optimism and lipids accounting for covariates such as demographic characteristics (e.g., education) and health status (e.g., chronic medical conditions). After adjusting for covariates, results suggested that greater optimism was associated with higher HDL cholesterol and lower triglycerides. Optimism was not associated with LDL or total cholesterol. Findings were robust to a variety of modeling strategies that took into consideration the effect of treatment for cholesterol problems. Results further indicated that diet and body mass index may link optimism with lipids. In conclusion, this is the first study to suggest that optimism is associated with a healthy lipid profile; moreover, these associations may be explained, in part, by having healthier behaviors and a lower body mass index.

Keywords: optimism, lipids, cholesterol, triglycerides

INTRODUCTION

This study investigated a cardiovascular risk factor that has yet to be empirically investigated in relation to optimism – namely, serum lipids. Optimism and lipids were expected to be associated because lipid profiles are driven in part by health behaviors and optimism is linked with healthier behaviors such as eating a balanced diet, exercising, and consuming moderate amounts of alcohol.1–4 We hypothesized that higher levels of optimism would be associated with a healthier lipid profile (i.e., more high density lipoprotein [HDL] cholesterol and less total cholesterol, low density lipoprotein [LDL] cholesterol, and triglycerides), controlling for potential confounders (i.e., demographic characteristics and health status). Moreover, we hypothesized that the association between optimism and lipid levels would be partially explained by health behaviors such as moderate alcohol consumption, exercise, diet, and the absence of cigarette smoking. To investigate these hypotheses, we conducted cross-sectional analyses in men and women from the Midlife in the United States (MIDUS) study.

METHODS

The MIDUS study was started in 1995 to better understand connections between psychosocial factors, aging, and health in men and women ages 25–74 years. More than 4,000 individuals were first recruited either by random digit dialing or by oversampling select metropolitan areas.5 Twin pairs and 1 or more siblings of randomly selected participants were recruited when possible, resulting in a total baseline sample of 7,108. A longitudinal follow-up comprised of 5 distinct projects was initiated 9–10 years later. The current investigation was based on a subsample of respondents from the longitudinal follow-up who completed the psychosocial project and the biomarker project. The psychosocial project – which entailed a phone interview and self-administered questionnaires – was completed by 5,895 of the original 7,108 participants and included measures of optimism and demographic factors. Participants who completed the psychosocial project and who were healthy enough to travel to a research clinic were eligible for the biomarker project, which was conducted an average of 26 months later (standard deviation [SD] = 14.66; range 2 to 62 months). The biomarker project was an in-depth, multiday assessment with an overnight stay that yielded measures of lipids, health status, and health behaviors, among other things. Due to the substantial commitment required, 39.3% (n = 1,255) of 3,191 eligible men and women participated (43.1% participated after adjusting for those who could not be contacted or located).6 Of eligible participants, those who participated in the biomarker project did not differ from those who did not with regard to age, sex, race, marital status, income, chronic disease, or body mass index (BMI), but they were more highly educated.6 Only participants with complete data on optimism, lipid levels, potential confounders, and pathway variables were included, yielding an analytic sample of 990. This research was approved by the appropriate institutional review boards and participants provided consent.

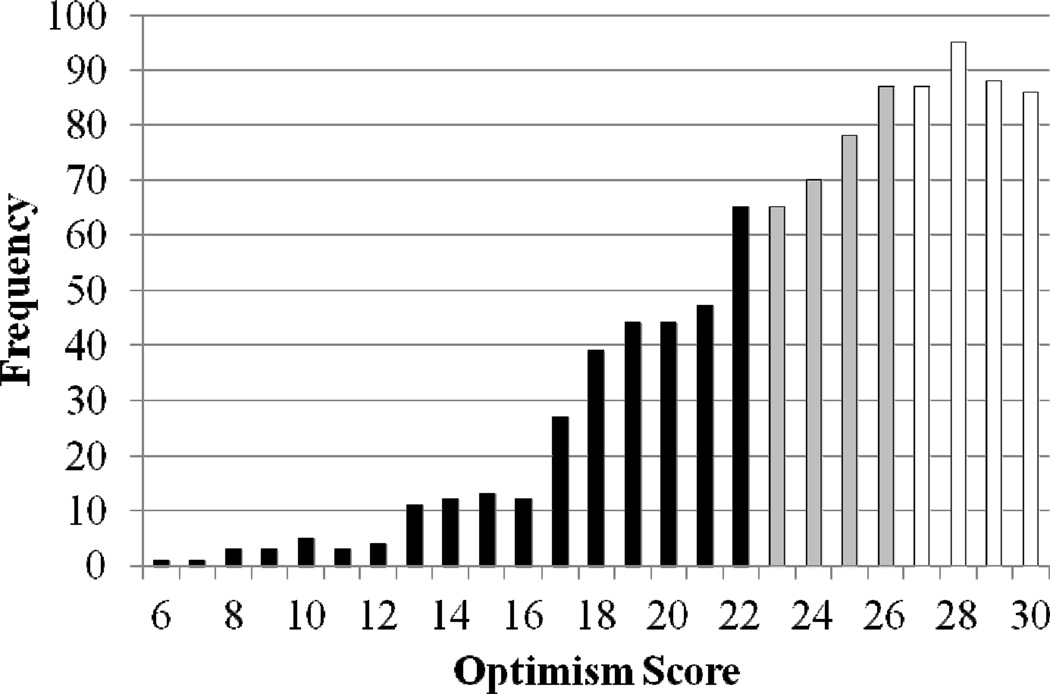

The 6-item Life Orientation Test-Revised was used to assess optimism.7 Participants indicated the extent to which they agreed (1= agree a lot to 5 = disagree a lot) with 3 positively-worded items (“I expect more good things to happen to me than bad,” “I’m always optimistic about my future,” “In uncertain times I usually expect the best”) and 3 negatively-worded items (“I hardly ever expect things to go my way,” “If something can go wrong for me it will,” “I rarely count on good things happening to me”). Because optimism may best be characterized by endorsing both positively-worded items and rejecting negatively-worded items,8 we followed recommendations to use the 6-item composite rather than the 3-item subscales.9 Positively-worded items were reverse scored and added to negatively-worded items to create a total optimism score ranging from 6–30 (Figure 1; α = 0.82). Higher values indicated more optimism and the total score was standardized (mean [M] = 0, SD = 1) for greater interpretability.

FIGURE 1.

The frequency distribution of 990 optimism scores (mean = 23.95, standard deviation = 4.69) with black representing the lowest tertile of optimism (6–22), gray representing the middle tertile of optimism (23–26), and white representing the highest tertile of optimism (27–30).

Participants traveled to 1 of 3 clinical research sites for 2 days of biological assessment. On the second morning of the visit, participants provided a fasting blood sample for a lipid panel (in mg/dL) of total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, and triglycerides. Samples were initially stored in a −60° C to −80° C freezer at each site and then frozen serum (1 mL aliquots) was shipped on dry ice to Meriter Laboratories in Madison, Wisconsin and stored in a −65° C freezer. All assays were performed with a Cobas Integra® analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, Indiana). An enzymatic colorimetric assay was used for total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and triglycerides; LDL cholesterol was derived with the Friedewald calculation10 (if triglyceride levels were >400 mg/dL, observed values were replaced with 400 mg/dL for calculating LDL cholesterol). From the total biomarker project sample, total cholesterol assays ranged from 0–800 mg/dL (reference range <200 mg/dL); the inter-assay coefficient of variation (CV) was 1.4–1.9% and intra-assay CV was 0.5–0.8%. HDL cholesterol assays ranged from 0–155 mg/dL (reference range 40–85 mg/dL); the inter-assay CV was 2.2–2.3% and intra-assay CV was 1.1–1.5%. Triglycerides assays ranged from 0–875 mg/dL (reference range <150 mg/dL); the inter-assay CV was 1.9% and intra-assay CV was 1.6%. The LDL cholesterol inter-assay CV was 10.11% (reference range 60–129 mg/dL).

Analyses controlled for factors known to be associated with lipid profiles. Demographics were self-reported and included age (in years), sex, race (white, non-white), education (< high school degree, high school degree, some college, ≥ college degree), household income, and months between assessment of optimism and serum lipids. Health status included chronic conditions (none, 1 condition or more) and blood pressure medication use (no, yes). The presence of chronic conditions (heart disease, hypertension, stroke, or diabetes) was assessed by the item “Have you ever had any of the following conditions or illnesses diagnosed by a physician?” Medications related to corticosteroids and depression were also considered, but were not included in final models because they were not associated with lipids in age-adjusted regression analyses. Categorical variables were dummy-coded prior to inclusion in the models.

To examine optimism’s independent effects from psychological ill-being, negative affect was controlled in secondary analyses. Negative affect was assessed during the psychosocial project using 5 items from a widely-used and psychometrically valid scale.11 Participants indicated the extent to which they felt afraid, jittery, irritable, ashamed, and upset in the past 30 days (1 = none of the time to 5 = all of the time). Following prior work in MIDUS, an average score was calculated if at least 1 item was rated; higher scores reflected more negative affect.

Potential behavioral pathways included smoking status (current smoker, past smoker, never smoker), average number of drinks consumed/day in the past month, regular exercise at least 3 times per week for 20 minutes (no, yes), and prudent diet. Smoking status and exercise were dummy-coded for statistical analysis. For diet, participants indicated their consumption of food categories during an average day or week. Consistent with previous research,12 a prudent diet score was calculated by giving participants a point for consuming: 3 or more servings/day of fruit and vegetables, 3 or more servings/day of whole grains, 1 or more serving/week of fish, 1 or more serving/week of lean meat, no sugared beverages, 2 or fewer servings/week of beef or high fat meat, and food at a fast food restaurant < once per week. Scores ranged from 0 to 7 (M = 4.24, SD = 1.39); higher scores indicated healthier diet. Because BMI is a product of health behaviors and genetics, we also investigated its potential role as a mediator. BMI (in standardized kg/m2) was measured by clinical staff during the biological assessment.

Statistical analyses were conducted in SAS 9.2. Given that treatment for cholesterol problems may bias findings, past work has routinely excluded participants who are receiving treatment. However, such an approach is not recommended because it discards relevant information, reduces power, and biases parameter estimates.13 Thus, following previous research, the lipid levels of those individuals who were taking cholesterol medicine (n = 284) were corrected for the typical effect of such treatment.14–16 That is, we increased levels of total cholesterol by 20%, LDL cholesterol by 35%, and triglycerides by 15%; we decreased levels of HDL cholesterol by 5%. Because the distribution of triglyceride scores was skewed and kurtotic, triglyceride scores were log transformed. Total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and LDL cholesterol had approximately normal distributions and were not transformed.

Each lipid served as an outcome in a series of linear regression models. The minimally-adjusted model included demographics (age, sex, race, education, income, and time between psychosocial and biological assessments) and optimism as predictors. A second multivariable-adjusted model added health status (chronic conditions and blood pressure medication) to the first model. Sensitivity analyses examined whether results differed when: 1) original lipid scores for all participants were maintained, regardless of the use of cholesterol medication (an approach where associations may be biased due to treatment), 2) participants taking cholesterol medication were excluded, and 3) use of cholesterol medication was included as a covariate.

Additional models examined whether health behaviors and BMI were on the pathway between optimism and lipids in minimally-adjusted models. However, because all data for relevant covariates were cross-sectional we did not formally test mediation and acknowledge that the direction of effects could be reversed. Instead, we examined how the regression coefficient for optimism changed when it was the sole predictor versus when a potential pathway variable was added to the model.17 When the regression coefficient for optimism was reduced (as indicated by a change of 10% or more) with the addition of a potential pathway variable, this suggested that the pathway variable partly explained optimism’s association with lipids.

In secondary analyses, negative affect was controlled in minimally-adjusted models and also used to stratify minimally-adjusted models. We also conducted logistic regression analyses for each lipid to see if optimism was associated with the probability of being at high risk for unhealthy lipid levels (defined as taking cholesterol medication, diagnosed by a physician as having cholesterol problems, or exceeding conventional cut-points for having high [or in the case of HDL cholesterol low] lipid levels). To account for the clustering of data due to presence of sibling and twin pairs in the cohort, we also reran primary statistical analyses with generalized estimating equations. When primary statistical analyses were conducted with generalized estimating equations, results were nearly identical to those described. This suggests that the presence of clustering in the analytic sample did not bias parameter estimates or standard errors. In the interest of interpretability, we present findings from primary statistical analyses. We also examined whether the association between optimism and lipid levels differed by race, but no differences were evident so results are not presented.

RESULTS

Participants were on average 55.12 years of age (SD = 11.78), with a range from 34 to 84 years. Men comprised 45% of the sample (n = 449) and women comprised 55% of the sample (n = 541). The vast majority of the sample was white (93%; n = 923). Average lipid levels were 196.62 mg/dL (SD = 38.00; 1st quartile = 171.00; 2nd quartile = 194.40; 3rd quartile = 218.40) for total cholesterol, 54.08 mg/dL (SD = 17.63; 1st quartile = 41.00; 2nd quartile = 51.64; 3rd quartile = 64.21) for HDL cholesterol, and 115.41 mg/dL (SD = 35.28; 1st quartile = 91.12; 2nd quartile = 111.75; 3rd quartile = 136.00) for LDL cholesterol. The average value of triglycerides was 135.42 (SD = 82.12; 1st quartile = 81.00; 2nd quartile = 113.85; 3rd quartile = 166.00) prior to transformation. Tables 1–2 show the distribution of covariates according to optimism level and correlations between optimism and covariates. More optimistic individuals tended to be older, have higher levels of education and income, engage in healthier behaviors, and report less negative affect compared with their less optimistic peers.

TABLE 1.

Distribution of participant characteristics according to level of optimism.a

| Characteristic Percentages or Mean (Standard Deviation) |

Optimism | pb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (n = 334) |

Moderate (n = 300) |

High (n = 356) |

||

| Age (years) | 53.13 (11.68) | 56.58 (12.36) | 55.75 (11.15) | 0.0005 |

| Sex | 0.33 | |||

| Male | 48.50% | 44.67% | 42.98% | |

| 36.08% | 29.84% | 34.08% | ||

| Female | 51.50% | 55.33% | 57.02% | |

| 31.79% | 30.68% | 37.52% | ||

| Race | 0.24 | |||

| White | 91.62% | 95.00% | 93.26% | |

| 33.15% | 30.88% | 35.97% | ||

| Non-white | 8.38% | 5.00% | 6.74% | |

| 41.79% | 22.39% | 35.82% | ||

| Education | < 0.0001 | |||

| Less than a high school degree | 5.69% | 2.33% | 2.53% | |

| 54.29% | 20.00% | 25.71% | ||

| High school degree | 26.05% | 21.00% | 15.17% | |

| 42.65% | 30.88% | 26.47% | ||

| Some college | 32.34% | 28.67% | 25.56% | |

| 37.89% | 30.18% | 31.93% | ||

| College degree or more | 35.93% | 48.00% | 56.74% | |

| 25.75% | 30.90% | 43.35% | ||

| Income (US dollars in thousands) | 68.11 (54.32) | 75.58 (57.97) | 85.87 (65.12) | 0.0004 |

| Time between assessments (months) | 25.91 (14.64) | 26.15 (14.73) | 26.39 (14.66) | 0.91 |

| Chronic conditions | 0.74 | |||

| Yes | 42.22% | 44.00% | 41.01% | |

| 33.65% | 31.50% | 34.84% | ||

| No | 57.78% | 56.00% | 58.99% | |

| 33.80% | 29.42% | 36.78% | ||

| Blood pressure medication | 0.64 | |||

| Yes | 33.83% | 37.00% | 33.99% | |

| 32.75% | 32.17% | 35.07% | ||

| No | 66.27% | 63.00% | 66.01% | |

| 34.26% | 29.30% | 36.43% | ||

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 29.71 (6.60) | 28.76 (5.51) | 28.91 (5.85) | 0.10 |

| Smoking status | < 0.0001 | |||

| Current | 17.66% | 9.00% | 7.30% | |

| 52.68% | 24.11% | 23.21% | ||

| Past | 30.24% | 36.33% | 31.74% | |

| 31.27% | 33.75% | 34.98% | ||

| Never | 52.10% | 54.67% | 60.96% | |

| 31.35% | 29.55% | 39.10% | ||

| Alcohol consumption (drinks/day) | 1.34 (1.40) | 1.10 (1.23) | 1.15 (1.39) | 0.06 |

| Prudent diet | 3.90 (1.45) | 4.29 (1.32) | 4.51 (1.33) | < 0.0001 |

| Regular exercise | 0.008 | |||

| Yes | 74.25% | 84.00% | 80.62% | |

| 31.51% | 32.02% | 36.47% | ||

| No | 25.75% | 16.00% | 19.38% | |

| 42.36% | 23.65% | 33.99% | ||

| Negative affect | 1.76 (0.61) | 1.48 (0.43) | 1.35 (0.34) | < 0.0001 |

| Total cholesterol | 198.15 | 195.55 | 196.08 | 0.65 |

| (38.06) | (38.29) | (37.77) | ||

| High density lipoprotein cholesterol | 52.29 (17.64) | 53.48 (16.55) | 56.26 (18.30) | 0.01 |

| Low density lipoprotein cholesterol | 118.07 | 114.42 | 113.74 | 0.23 |

| (35.55) | (35.35) | (34.93) | ||

| Triglyceridesc | 140.53 | 137.99 | 128.47 | 0.13 |

| (86.62) | (88.74) | (70.99) | ||

Percentages at the top of each cell refer to the column % and percentages at the bottom of each cell refer to the row %.

p-values come from χ2 or analysis of variance tests.

Prior to log transformation.

TABLE 2.

Correlation coefficients for the association between optimism and participant characteristics (N = 990).

| Participant Characteristic | Association with Optimism | |

|---|---|---|

| r | p | |

| Age | .18 | < 0.0001 |

| Sexa | .02 | 0.49 |

| Raceb | −.04 | 0.21 |

| Educationc | .18 | < 0.0001 |

| Income | .14 | < 0.0001 |

| Time between assessments | .01 | 0.71 |

| Chronic conditionsd | .003 | 0.93 |

| Blood pressure medicatione | .03 | 0.43 |

| Body mass index | −.07 | 0.03 |

| Smoking statusf | .13 | < 0.001 |

| Alcohol consumption | −.07 | 0.03 |

| Prudent diet | .21 | < 0.0001 |

| Regular exerciseg | .06 | 0.04 |

| Negative affect | −.45 | < 0.0001 |

Sex: men = 0, women = 1

Race: white = 0, non-white = 1

Education: less than high school degree = 1, high school degree = 2, some college = 3, college degree or more = 4

Chronic conditions: no = 0, yes = 1

Blood pressure medication: no = 0, yes = 1

Smoking status: 1 = current smoker, 2 = past smoker, 3 = never smoker

Regular exercise: no = 0, yes = 1

Optimism was not associated with LDL cholesterol and total cholesterol, but was associated with HDL cholesterol and triglycerides in the expected directions (Table 3). For each SD increase in optimism, levels of HDL cholesterol were more than 1 mg/dL higher. For each SD increase in optimism, levels of triglycerides were 3% lower. Findings were only modestly attenuated after multivariable adjustment.

TABLE 3.

Unstandardized parameter estimates [95% confidence interval] for the association between 1 standard deviation increase in optimism and lipid levels (N = 990).

| Lipids (mg/dL) | Model 1a | Model 2b |

|---|---|---|

| Total cholesterol | −0.64 [−3.11, 1.83] | −0.61 [−3.09, 1.86] |

| High density lipoprotein cholesterol | 1.32** [0.28, 2.37] | 1.21* [0.18, 2.25] |

| Low density lipoprotein cholesterol | −1.18 [−3.47, 1.11] | −1.18 [−3.48, 1.11] |

| Triglycerides (log transformed) | −0.03~ [−0.07, 0.0009] | −0.03~ [−0.06, 0.005] |

Adjusted for demographics (age, sex, race, education, income, and time between assessments)

Adjusted for demographics and health status (chronic conditions and blood pressure medication)

p ≤ .10,

p ≤ .05,

p ≤ .01

When the original lipid scores were used without correcting for cholesterol treatment, results were virtually identical to those that adjusted for the average effect of lipid medication (data not shown). Similarly, when examining the association between optimism and lipids among the 706 participants who were not taking cholesterol medication, results were mostly indistinguishable. For example, among participants not taking cholesterol medication, greater optimism was associated with higher levels of HDL cholesterol (b = 1.39, 95% CI [0.15, 2.63], p = 0.03) and lower levels of triglycerides (b = −0.04, 95% CI [−0.08, 0.002], p = 0.06) in minimally-adjusted models. Findings were also nearly identical in models that controlled for cholesterol medication. For example, in minimally-adjusted models, HDL cholesterol (b = 1.27, 95% CI [0.23, 2.31], p = 0.02) and triglycerides (b = −0.03, 95% CI [−0.06, 0.003], p = 0.07) were still positively and inversely associated with optimism, respectively. Consistent with the models that adjusted for the typical effect of medication, LDL cholesterol and total cholesterol were not associated with optimism in any of the sensitivity analyses. Thus, the association between optimism and lipid profiles was robust regardless of cholesterol treatment.

Because optimism was related to higher HDL cholesterol and lower triglycerides, we examined whether the associations might be explained by health behaviors and BMI (Table 4). Prudent diet, smoking status, and BMI reduced the relationship between optimism and HDL cholesterol by more than 10%. When all health behaviors and BMI were included in the model simultaneously, the association between optimism and HDL cholesterol was reduced by half and the effect of optimism was no longer statistically significant. Prudent diet and BMI also reduced optimism’s association with triglycerides; when all pathway variables were included in the model the association between optimism and triglycerides was reduced by half.

TABLE 4.

Change in the association between optimism and lipid levels when potential pathway variables were included individually and then all together in Model 1a (N = 990).

| Predictors | High density lipoprotein cholesterol | Triglycerides (log transformed) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | %Δ | b | SE | %Δ | |

| Optimism and demographics | 1.32** | 0.53 | – | −0.03~ | 0.02 | – |

| + Prudent diet | 0.86~ | 0.53 | −35% | −0.02 | 0.02 | −32% |

| + Exercise | 1.21* | 0.53 | −9% | −0.03~ | 0.02 | −10% |

| + Smoking status | 1.17* | 0.54 | −12% | −0.03~ | 0.02 | .2% |

| + Alcohol consumption | 1.39** | 0.53 | 6% | −0.03~ | 0.02 | −4% |

| + Body mass index | 1.12* | 0.50 | −15% | −0.03 | 0.02 | −21% |

| + All pathway variablesb | 0.64 | 0.50 | −52% | −0.01 | 0.02 | −54% |

Adjusted for demographics (age, sex, race, education, income, and time between assessments)

Adjusted for demographics, prudent diet, exercise, smoking status, alcohol consumption, and body mass index

p ≤ .10,

p ≤ .05,

p ≤ .01

When negative affect was included with optimism in minimally-adjusted models, previously reported findings were slightly attenuated. Optimism remained associated with HDL cholesterol (b = 1.28, 95% CI [0.13, 2.43], p = 0.03), but negative affect was not (b = −0.20, 95% CI [−2.48, 2.07], p = 0.86). Optimism was not associated with triglycerides, but negative affect was (optimism: b = −0.01, 95% CI [−0.05, 0.02], p = 0.45; negative affect: b = 0.09, 95% CI [0.02, 0.16], p = 0.02). Neither optimism nor negative affect were associated with LDL cholesterol and total cholesterol. Furthermore, we also stratified these models by negative affect such that 58% of the sample was classified as having lower levels of negative affect and 42% of the sample was classified as having higher levels. Among participants with relatively lower levels of negative affect, optimism’s association with HDL cholesterol (b = 2.66, 95% CI [1.05, 4.26], p = 0.001) and triglycerides (b = −0.07, 95% CI [−0.12, −0.02], p = 0.009) paralleled primary findings. Associations among participants with relatively more negative affect were not statistically significant. The interaction term between optimism and negative affect was marginally significant for HDL cholesterol (p = .06) and statistically significant for triglycerides (p = .009).

In analyses modeling risk of unhealthy lipid levels, patterns were generally consistent. Controlling for confounding variables in minimally-adjusted and multivariable-adjusted models, there was a 7–14% reduction in the odds of having unhealthy lipid levels for every SD increase in optimism (Table 5). Findings were strongest for HDL cholesterol and triglycerides.

TABLE 5.

Odds ratios [95% confidence interval] for the association between 1 standard deviation increase in optimism and presence of unhealthy lipid levelsa (N = 990).

| Lipids | Model 1b | Model 2c |

|---|---|---|

| Total cholesterol | 0.89~ [0.78, 1.02] | 0.91 [0.79, 1.04] |

| High density lipoprotein cholesterol | 0.86* [0.75, 0.98] | 0.88~ [0.76, 1.01] |

| Low density lipoprotein cholesterol | 0.91 [0.79, 1.04] | 0.93 [0.81, 1.07] |

| Triglycerides | 0.87* [0.76, 1.00] | 0.89~ [0.77, 1.03] |

Risk of unhealthy lipid levels was defined as cholesterol medication, physician diagnosis of having cholesterol problems, or exceeding conventional cut-points for unhealthy lipid levels (i.e., total cholesterol ≥240 mg/dL, HDL cholesterol <40 mg/dL for men and <50 mg/dL for women, LDL cholesterol ≥160 mg/dL, and triglycerides ≥200 mg/dL)

Adjusted for demographics (age, sex, race, education, income, and time between assessments)

Adjusted for demographics and health status (chronic conditions and blood pressure medication)

p ≤ .10,

p ≤ .05

DISCUSSION

This study investigated the cross-sectional association between optimism and lipids. Consistent with predictions, more optimistic attitudes were associated with higher HDL cholesterol and lower triglycerides. Specifically, for every SD increase in optimism, HDL cholesterol levels were 1 mg/dL higher and triglyceride levels were 3% lower. The size of these associations is relatively small although clinically significant; for example, a 1 mg/dL increase in HDL cholesterol is related to a 2–3% reduction in risk of coronary heart disease.18 The magnitude of association between optimism and lipids is also comparable to the association between these lipids and health behaviors such as physical activity. Meta-analyses show that exercising can improve levels of HDL cholesterol and triglycerides by 4–6%19 or increase HDL cholesterol levels by 2.53 mg/dL.20 Moreover, even small improvements at the individual level may translate into shifts in the distribution of risk at the population level.21 Thus, our findings suggest that optimism may play a meaningful and non-trivial role in healthy lipid profiles.

Optimism was not associated with total cholesterol or LDL cholesterol. Though it is unclear why only HDL cholesterol and triglycerides were marginally or significantly related to optimism, such findings are consistent with research on other psychosocial factors.22 For example, the personality traits of conscientiousness and impulsivity were more consistently associated with HDL cholesterol and triglycerides than LDL cholesterol or total cholesterol.23

Optimism’s association with HDL cholesterol and triglycerides was robust to alternative modeling strategies. Results did not measurably change when lipid levels were adjusted for the typical effect of medication, when lipid levels were based on original unadjusted values, when individuals taking cholesterol medication were excluded, or when demographics, health status, and cholesterol medication were controlled. Findings for triglycerides were somewhat attenuated when analyses adjusted for negative affect, but this could be due to the correlation between optimism and negative affect. That said, optimism’s association with HDL cholesterol and triglycerides was evident among individuals with low negative affect. This suggests that optimism is not merely a proxy for the absence of distress, but exhibits a monotonic relationship with lipids across the score range. Findings were also maintained for high-risk cut-points.

Analyses also pointed to several behavioral pathways that can explain part of the observed association between optimism and a healthier lipid profile. Consistent with past work, optimism was associated with smoking status, alcohol consumption, dietary intake, and exercise.1–4 Adding prudent diet and BMI to regression models noticeably attenuated optimism’s association with HDL cholesterol and triglycerides. This suggests that optimistic individuals may be better equipped than their less optimistic peers to meet the challenges of engaging in healthy behavior and maintaining a healthy BMI.24 However, rather than merely operating as a proxy for healthy behavior, optimism may serve as a precursor to healthy behavior by motivating individuals to behave in ways that are consistent with their favorable expectations for the future. That is, expectations about the effects of a particular behavior both precede and influence the behavior itself; the expectations surrounding a behavior are separate from the behavior itself.25,26 Notably, health behaviors and BMI did not explain the entire association between optimism and lipids, so there are likely other relevant factors for explaining the optimism-lipid relation. For example, inflammation has been linked with both optimism27,28 and metabolic dysfunction,29 which hints that optimism may be associated with lipids through a direct inflammatory pathway.

A clear limitation of the present investigation is the cross-sectional data. Whether optimism leads to healthier lipid profiles or whether healthier lipid profiles (and better health in general) lead to optimism cannot be determined, although optimism was often measured at least several months prior to lipid profiles. Notably, optimism did not vary substantially according to whether individuals were taking lipid medications, reducing somewhat the concern that lipid levels determine optimism. Although we suspect that optimism does in fact influence lipid levels as an upstream determinant, it is also possible that the association is bidirectional. Moreover, an unmeasured third variable could also determine both optimism and lipid profiles. Future prospective and experimental research is needed to more clearly establish the direction of effects, investigate whether associations differ depending on health status, and examine whether controlling other measures of ill-being alters findings. Strengths of the research include a well-validated measure of optimism and objectively-measured lipids, which limits concerns regarding self-report bias. Additional strengths include the ability to consider potential confounding and pathway variables. Taken together, this research suggests that an optimistic outlook is related to a healthier lipid profile. Thus, considering optimism in the context of lipids may suggest new strategies for prevention and intervention to improve cardiovascular health.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the research staff at Georgetown University, University of Wisconsin-Madison, and University of California, Los Angeles.

Support: Support for this research was provided by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation through a grant, “Exploring the Concept of Positive Health,” to the Positive Psychology Center of the University of Pennsylvania, Martin Seligman, project director. The original Midlife in the United States study was supported by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Successful Midlife Development. Follow-up data collection was supported by the National Institute on Aging (P01-AG020166).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Giltay EJ, Geleijnse JM, Zitman FG, Buijsse B, Kromhout D. Lifestyle and dietary correlates of dispositional optimism in men: The Zutphen Elderly Study. J Psychosom Res. 2007;63:483–490. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kavussanu M, McAuley E. Exercise and optimism: Are highly active individuals more optimistic? Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology. 1995;17:246–258. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kelloniemi H, Ek E, Laitinen J. Optimism, dietary habits, body mass index and smoking among young Finnish adults. Appetite. 2005;45:169–176. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steptoe A, Wright C, Kunz-Ebrecht SR, Iliffe S. Dispositional optimism and health behaviour in community-dwelling older people: Associations with healthy ageing. Br J Health Psychol. 2006;11:71–84. doi: 10.1348/135910705X42850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Radler BT, Ryff CD. Who participates? Accounting for longitudinal retention in the MIDUS National Study of Health and Well-Being. J Aging Health. 2010;22:307–331. doi: 10.1177/0898264309358617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dienberg Love G, Seeman TE, Weinstein M, Ryff CD. Bioindicators in the MIDUS National Study: Protocol, measures, sample, and comparative context. J Aging Health. 2010;22:1059–1080. doi: 10.1177/0898264310374355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scheier MF, Carver CS, Bridges MW. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): A reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1994;67:1063–1078. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.67.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ryff CD, Singer B. Reply: What to do about positive and negative items in studies of psychological well-being and ill-being? Psychother Psychosom. 2007;76:61–62. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Segerstrom SC, Evans DR, Eisenlohr-Moul TA. Optimism and pessimism dimensions in the life orientation test-revised: Method and meaning. J Res Pers. 2011:126–129. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem. 1972;18:499–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54:1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hu FB. Dietary pattern analysis: a new direction in nutritional epidemiology. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2002;13:3–9. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200202000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tobin MD, Sheehan NA, Scurrah KJ, Burton PR. Adjusting for treatment effects in studies of quantitative traits: antihypertensive therapy and systolic blood pressure. Stat Med. 2005;24:2911–2935. doi: 10.1002/sim.2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ki M, Pouliou T, Li L, Power C. Physical (in)activity over 20 y in adulthood: associations with adult lipid levels in the 1958 British birth cohort. Atherosclerosis. 2011;219:361–367. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.07.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kraja AT, Borecki IB, North K, Tang W, Myers RH, Hopkins PN, Arnett D, Corbett J, Adelman A, Province MA. Longitudinal and age trends of metabolic syndrome and its risk factors: the Family Heart Study. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2006;3:41. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-3-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pinto Pereira SM, Ki M, Power C. Sedentary behaviour and biomarkers for cardiovascular disease and diabetes in mid-life: the role of television-viewing and sitting at work. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e31132. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Janicki-Deverts D, Cohen S, Matthews KA, Gross MD, Jacobs DR., Jr Socioeconomic status, antioxidant micronutrients, and correlates of oxidative damage: The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study. Psychosom Med. 2009;71:541–548. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31819e7526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gordon DJ, Probstfield JL, Garrison RJ, Neaton JD, Castelli WP, Knoke JD, Jacobs DR, Jr, Bangdiwala S, Tyroler HA. High-density lipoprotein cholesterol and cardiovascular disease. Four prospective American studies. Circulation. 1989;79:8–15. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.79.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Halbert JA, Silagy CA, Finucane P, Withers RT, Hamdorf PA. Exercise training and blood lipids in hyperlipidemic and normolipidemic adults: a meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1999;53:514–522. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kodama S, Tanaka S, Saito K, Shu M, Sone Y, Onitake F, Suzuki E, Shimano H, Yamamoto S, Kondo K, Ohashi Y, Yamada N, Sone H. Effect of aerobic exercise training on serum levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol: a meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:999–1008. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.10.999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Friedman HS, Booth-Kewley S. The 'disease-prone personality': A meta-analytic view of the construct. Am Psychol. 1987;42:539–555. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.42.6.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steptoe A, Demakakos P, de Oliveira C, Wardle J. Distinctive biological correlates of positive psychological well-being in older men and women. Psychosom Med. 2012;74:501–508. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31824f82c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sutin AR, Terracciano A, Deiana B, Uda M, Schlessinger D, Lakatta EG, Costa PT., Jr Cholesterol, triglycerides, and the Five-Factor Model of personality. Biol Psychol. 2010;84:186–191. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2010.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rasmussen HN, Wrosch C, Scheier MF, Carver CS. Self-regulation processes and health: The importance of optimism and goal adjustment. J Pers. 2006;74:1721–1747. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2006.00426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scheier MF, Carver CS. Effects of optimism on psychological and physical well-being: Theoretical overview and empirical update. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1992;16:201–228. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scheier MF, Carver CS. Goals and confidence as self-regulatory elements underlying health and illness behavior. In: Cameron LD, Leventhal H, editors. The self-regulation of health and illness behaviour. London: Routledge; 2003. pp. 17–41. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ikeda A, Schwartz J, Peters JL, Fang S, Spiro A, Sparrow D, Vokonas P, Kubzansky LD. Optimism in relation to inflammation and endothelial dysfunction in older men: The VA Normative Aging Study. Psychosom Med. 2011;73:664–671. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3182312497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roy B, Diez-Roux AV, Seeman T, Ranjit N, Shea S, Cushman M. Association of optimism and pessimism with inflammation and hemostasis in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Psychosom Med. 2010;72:134–140. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181cb981b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hotamisligil GS. Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature. 2006;444:860–867. doi: 10.1038/nature05485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]