Abstract

Tau hyper-phosphorylation (p-Tau) and neuro-inflammation are hallmarks of neurodegeneration. Previous findings suggest that microglial activation via CX3CL1 promotes p-Tau. We examined inflammation and autophagic p-Tau clearance in lentiviral Tau and mutant P301L expressing rats and used lentiviral Aβ1–42 to induce p-Tau. Lentiviral Tau or P301L expression significantly increased caspase-3 activity and TNF-α, but CX3CL1 was significantly higher in animals expressing Tau compared to P301L. Lentiviral Aβ1–42 induced p-Tau 4 weeks post-injection, and increased caspase-3 activation (8-fold) and TNF-α levels. Increased levels of ADAM-10/17 were also detected with p-Tau. IL-6 levels were increased but CX3CL1 did not change in the absence of p-Tau (2 weeks); however, p- Tau reversed these effects, which were associated with increased microglial activity. We observed changes in autophagic markers, including accumulation of autophagic vacuoles (AVs) and p-Tau accumulation in autophagosomes but not lysosomes, suggesting alteration of autophagy. Taken together, microglial activation may promote p-Tau independent of total Tau levels via CX3CL1 signaling, which seems to depend on interaction with inflammatory markers, mainly IL-6. The simultaneous change in autophagy and CX3CL1 signaling suggests communication between microglia and neurons, raising the possibility that accumulation of intraneuronal amyloid, due to lack of autophagic clearance, may lead microglia activation to promote p-Tau as a tag for phagocytic degradation.

Keywords: Tau phosphorylation, CX3CL1, inflammation, autophagosome, autophagy

Introduction

Tauopathies are pathologically characterized by accumulation of insoluble aggregates of hyper-phosphorylated Tau (p-Tau) in neurons and glia (Hasegawa, et al., 1998, Hutton, et al., 1998, Jiang, et al., 2003, Poorkaj, et al., 1998). Extracellular β-amyloid (Aβ) plaques and intracellular p-Tau-containing neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) are characteristics of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (Grundke-Iqbal, et al., 1986, Hardy and Allsop, 1991, Hardy and Higgins, 1992). NFTs correlate highly with the degree of dementia in AD (Braak and Braak, 1991). Other Tauopathies include progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), corticobasal degeneration (CBD), and frontotemporal dementia with Parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17 (FTDP-17) (Bird, et al., 1999, Gasparini, et al., 2007). Increased Tau is also detected in Parkinson’s disease (PD) brain, mainly striatum (Tobin, et al., 2008). Tau binds to and stabilizes microtubules in a process regulated by phosphorylation (Lindwall and Cole, 1984). Some findings report that Tau modification affects the flux of autophagy due to destabilization of microtubules and impairment of organelle movement (Dawson, et al., 2010, Dawson, et al., 2001, Gomez-Isla, et al., 1997, Harada, et al., 1994, Jimenez-Mateos, et al., 2006), while others suggest that Tau aggregates are removed by autophagy (Dolan and Johnson, 2010, Wang, et al., 2010).

In AD, Aβ and/or Tau are inflammatory stimuli that may provoke microglial activation (Ransohoff and Perry, 2009, Rogers, et al., 1996). However, it is unclear whether microglial activation has beneficial or detrimental effects in the brain (Cameron and Landreth, 2010, Frank-Cannon, et al., 2009, Wyss-Coray and Mucke, 2002). Fractalkine (CX3CL1) is a chemokine (Bazan, et al., 1997, Harrison, et al., 1998), which may regulate inflammation via neuron-microglia communication. Neurons secrete CX3CL1 (Harrison, et al., 1998), which exists in both membrane-bound and soluble forms (Hatori, et al., 2002). Increased levels of serum CX3CL1 are reported in patients with multiple sclerosis (Kastenbauer, et al., 2003, Tong, et al., 2000), traumatic brain injury (Rancan, et al., 2004) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) with CNS complications (Sporer, et al., 2003). Reduced levels of CX3CL1 receptors (CX3CR1) are also linked to age-related macular degeneration in humans (Combadiere, et al., 2007).

Recent developments reveal a crucial role for the autophagy pathway and proteins involved in regulating the immune response to balance the beneficial and detrimental effects of immunity and inflammation (Lee, et al., 2012, Levine, et al., 2011, Saitoh and Akira, 2010). We developed several gene transfer animal models via lentiviral delivery of human wild type Tau and P301L, which is a Tau mutation in exon 10 at codon 301, resulting in a Pro to Leu substitution, and is associated with FTDP- 17 (Mirra, et al., 1999). We also used lentiviral Aβ1–42 to induce accumulation of intracellular proteins and autophagy (Khandelwal, et al., 2011, Lonskaya, et al., 2012). We observed p-Tau accumulation, autophagic alterations and cell death in lentiviral gene transfer animal models within 4mm radius from the point of injection following expression of Aβ1–42 (Lonskaya, et al., 2012, Rebeck, et al., 2010), or lentiviral Tau or P301L in the rat cortex (Khandelwal, et al., 2011). Since alteration of normal autophagy and inflammation are reported in several human diseases (Lee, et al., 2012, Levine, et al., 2011, Saitoh and Akira, 2010), we determined whether autophagic defects are linked to neuro-inflammation via CX3CL1 signaling between neurons undergoing Aβ or Tau-induced autophagy and microglial activation. We used lentiviral gene transfer of wild type Tau and mutant P301L, which resulted in faster appearance of p-Tau (4 weeks) than traditional transgenic animals; and injected lentiviral Aβ1–42 to seed for p-Tau accumulation and induce autophagy without changing total Tau levels.

Methods & Materials

Stereotaxic injection- was performed to inject the lentiviral (Lv) constructs encoding either LacZ, Aβ1–42, Tau or P301L, into the primary motor cortex of two-month-old male Sprague-Dawley rats as previously described (Burns, et al., 2009, Khandelwal, et al., 2011, Rebeck, et al., 2010). Human 4 repeat wild type Tau and mutant P301L cDNA were each cloned into a pLenti6-D-TOPO (Invitrogen, Inc) plasmid under the control of a Cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter using TOPO cloning and atggctgagccccgccaggag as a forward primer and ccgaactgcgaggagcagctg as a reverse primer (Khandelwal, et al., 2011). To detect lentiviral expression, independent of the gene of interest, a 13- amino acid (Lys Pro Ile Pro Asn Pro Leu Leu Gly Leu Asp Ser Thr) epitope was inserted after the gene of interest and before PSV40 of the lentiviral plasmid. Lentiviral packaging was performed according to manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen, Inc). The stereotaxic coordinates of motor cortex were 2.8 mm lateral, 3.2 ventral, 2.7 mm posterior. Viral stocks were injected through a microsyringe pump controller (Micro4) using total pump (World Precision Instruments, Inc.) delivery of 6 µl at a rate of 0.2 µl/min. The needle remained in place at the injection site for an additional minute before slow removal over a period of 2 min. Animals were injected into the left side of M1 primary motor cortex with 1) a lentiviral-LacZ vector at 2 × 1010 m.o.i and the right side of the cortex 2) with 2×1010 m.o.i lentiviral-Tau; or 3) 2×1010 m.o.i lentiviral-P301L. Animals were all sacrificed 1-month post-injection, and LacZ and Aβ1–42, were sacrificed 2–4 weeks post-injection. A total of 4–8 animals of each treatment were used for Western blot, ELISA and immunohistochemistry and 4 animals for EM. A total of 74 animals were used in these studies according to Georgetown University Animal Care and Use Committee (GUACAC).

Western blot analysis- The cortex was dissected out and homogenized in 1xSTEN buffer (50 mM Tris (pH 7.6), 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 0.2 % NP-40, 0.2 % BSA, 20 mM PMSF and protease cocktail inhibitor) then centrifuged at 5,000g and the supernatant was collected. Histone deacetylase 6 (HDAC6) was probed (1:500) using rabbit polyclonal anti-HDAC6 (Cell Signaling Technology). Total Tau was probed with (1:1000) mouse monoclonal Tau-5 antibody (Thermo Scientific). Autophagy sampler kit (Cell Signaling Biotechnology) containing rabbit polyclonal anti-beclin-1 (1:1000) and rabbit polyclonal LC3-B (1:1000) were used. Rabbit polyclonal anti-actin (Thermo Scientific) was used (1:1000). ADAM-10 was probed (1:1000) with rabbit polyclonal antibody (Thermo Scientific), and ADAM-17 was probed with goat polyclonal antibody (Thermo Scientific). CX3CL1 was probed (1:1000) with rabbit polyclonal antibody (Thermo Scientific) and CX3CR1 was probed with (1:1000) rabbit polyclonal antibody (ThermoFisher). Human 4R repeat Tau was probed (1:500) mouse monoclonal antibody (Millipore), LAMP-2a was probed (1:500) rabbit polyclonal antibody (Aviva Systems) and LC3 was probed (1:500) with rabbit polyclonal antibody (ThermoFisher). V5 epitope was probed (1:500) with rabbit polyclonal antibody (Invitrogen). Western blots were quantified by densitometry using Quantity One 4.6.3 software (Bio Rad). Densitometry was obtained as arbitrary numbers measuring band intensity. Data were analyzed as mean±Standard deviation, using ANOVA, with Neumann Keuls multiple comparison between treatment groups.

Immunohistology was performed on 20µm-thick cortical brain sections using mouse monoclonal (1:200) anti-GFAP antibody (Thermo Scientific) and microglia were probed with rabbit polyclonal (1:200) anti-IBA-1 (Wako). Aβ1–42 was probed (1:200) with rabbit polyclonal specific anti-Aβ1– 42 antibody (Zymed Laboratories Inc.) or with (1:200) mouse monoclonal (4G8) antibody (Covance). Active caspase-3 was probed (1:200) with rabbit polyclonal antibody (Millipore Corp.). Total tau was probed (1:1000) with Tau-5 monoclonal antibody (Chemicon, Temecula, CA, USA). LC3-B was probed (1:100) with rabbit polyclonal anti-LC3-B antibody (Cell Signaling Biotechnology). Phosphorylated Tau was probed (1:1000) with polyclonal AT8 (1:1000) Serine-199/202 (Biosource, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and (1:1000) AT180 polyclonal (1:1000) threonine-231 (Biosource, Carlsbad, CA, USA). CX3CL1 was probed (1:100) with rabbit polyclonal antibody (Thermo Scientific) and human Aβ1–42 was probed (1:200) rabbit polyclonal antibody (Millipore).

Stereological methods- were applied by a blinded investigator using unbiased stereology analysis (Stereologer, Systems Planning and Analysis, Chester, MD) to determine the total positive cell counts in 20 cortical fields on at least 10 brain sections (~400 positive cells per animal) from each animal. These areas were selected across different regions on either side from the point of injection, and all values were averaged to account for the gradient of staining across 2.5 mm radius from the point of injection. An optical fractionator sampling method was used to estimate the total number of positive cells with multi-level sampling design. Cells were counted within the sampling frame determined optically by the fractionator and cells that fell within the counting frame were counted as the nuclei came into view while focusing through the z-axis.

Caspase-3 fluorometric activity assay- To measure caspase-3 activity in the animal models, we used EnzChek® caspase-3 assay kit #1 (Invitrogen) on cortical extracts and Z-DEVD-AMC substrate and the absorbance was read according to manufacturer’s protocol.

CX3CL1, IL-6 and TNF-α enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)- rat-specific CX3CL1 (Cayman) IL-6 or TNF-α (Invitrogen) were performed using 50µl (1 µg/µl) of cortical rat brain lysates, detected with CX3CL1, IL-6 or TNF-α primary antibody (3h) and 100µl anti-rabbit antibody (30min) at RT. Extracts were incubated with stabilized Chromogen for 30 minutes at RT and solution was stopped and read according to manufacturer's protocol.

Aβ and p-Tau ELISA- were performed using 50µl (1µg/µl) of whole hemisphere brain lysates, detected with 50µl human p-Tau (Ser396) or Aβ1–42 primary antibody (3h) and 100µl anti-rabbit antibody (30min.) at RT. Extracts were incubated with stabilized Chromogen for 30 minutes at RT and solution was stopped and read at 450nm, according to manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen).

Subcellular fractionation to isolate autophagic vacuoles- Animal brains were homogenized at low speed (Cole-Palmer homogenizer, LabGen 7, 115 Vac) in 1xSTEN buffer and centrifuged at 1,000g for 10 minutes to isolate the supernatant from the pellet. The pellet was re-suspended in 1xSTEN buffer and centrifuged once to increase the recovery of lysosomes. The pooled supernatants were then centrifuged at 100,000 rpm for 1 hour at 4°C to extract the pellet containing autophagic vacuoles (AVs) and lysosomes. The pellet was then re-suspended in 10 ml (0.33 g/ml) 50% Metrizamide and 10 ml in cellulose nitrate tubes. A discontinuous Metrizamide gradient was constructed in layers from bottom to top as follows: 6 ml of pellet suspension, 10 ml of 26%; 5 ml of 24%; 5 ml of 20%; and 5 ml of 10% Metrizamide (Marzella, et al., 1982). After centrifugation at 100,000 rpm for 1 hour at 4°C, the fraction floating on the 10% layer (Lysosome) and the fractions banding at the 24%/20% (AV 20) and the 20%/10% (AV10) Metrizamide interphases were collected by a syringe and examined.

Electron Microscopy- Brain tissue were fixed in (1:4, v:v) 4% paraformaldehyde-picric acid solution and 25% glutaraldehyde overnight, then washed 3x in 0.1M cacodylate buffer and osmicated in 1% osmium tetroxide/1.5% potassium ferrocyanide for 3h, followed by another 3x wash in distilled water. Samples were treated with 1% uranyl acetate in maleate buffer for 1 h, washed 3 × in maleate buffer (pH 5.2), then exposed to a graded cold ethanol series up to 100% and ending with a propylene oxide treatment. Samples are embedded in pure plastic and incubated at 60°C for 1–2 days. Blocks are sectioned on a Leica ultracut microtome at 95 nm, picked up onto 100 nm formvar-coated copper grids, and analyzed using a Philips Technai Spirit transmission EM.

Results

CX3CL1 signaling and detection of p-Tau

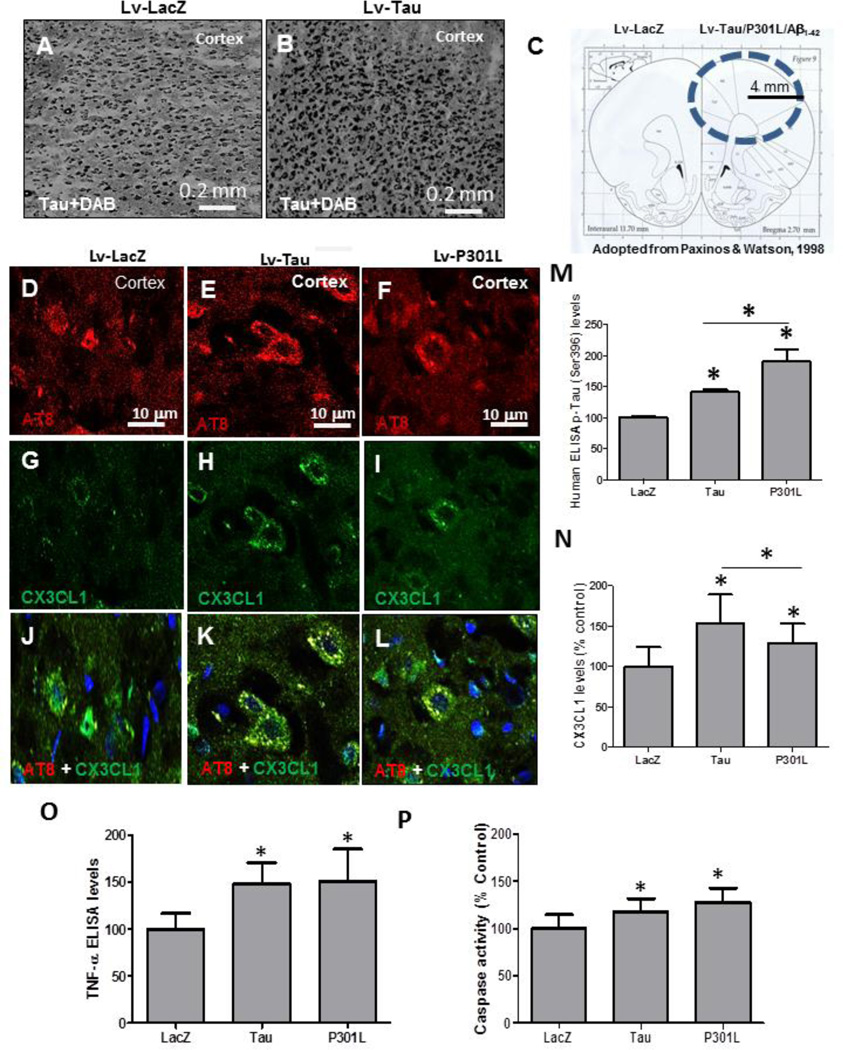

We sought to examine inflammatory mechanisms in animals expressing lentiviral Tau. We previously generated gene transfer animal models using lentiviral delivery of 4R human wild type Tau and mutant P301L into the rat primary motor cortex (Khandelwal, et al., 2011). Staining with Tau-5 antibody showed abundant Tau expression in the right hemisphere injected with lentiviral Tau (Fig. 1B&C) compared to contralateral LacZ injected hemisphere (Fig. 1A&C). The distribution of lentiviral expression was within 4 mm radius from the point of lentiviral injection (Fig. 1C) as we previously demonstrated (Burns, et al., 2009). Staining with AT8 antibody showed p-Tau in lentiviral Tau (Fig. 1E) and P301L (Fig. 1F) compared to LacZ injected hemisphere (Fig. 1D) 1-month post-injection. Co-staining with CX3CL1 antibody revealed higher levels of CX3XL1 in Tau (Fig. 1H) and P301L (Fig. 1I) expressing cortex compared to LacZ (Fig. 1G). p-Tau co-localized with CX3CL1 in animals injected with lentiviral Tau (Fig. 1K) and P301L (Fig. 1L) compared to LacZ (Fig. 1J). We previously could not detect any difference in the amount of p-Tau between lentiviral Tau and P301L injected animals using immunohistochemistry, but we observed different patterns of Tau modification on Western blot, suggesting higher levels of p-Tau in P301L injected hemispheres (Khandelwal, et al., 2011). To determine the amount of p-Tau in response to either Tau or mutant P301L we quantified p-Tau at Ser 396 using ELISA. Lentiviral expression of wild type Tau increased (48%) p-Tau levels (Fig. 1M) compared to LacZ, while expression of mutant P301L induced a significantly higher (76%) increase in p-Tau compared to both LacZ and wild type Tau (Fig. 1M, P<0.05, N=7 for Tau and 4 for P301L). A significant increase (54%) in CX3CL1 was detected by ELISA in Tau expressing cortex (Fig. 1N) compared to LacZ. Despite p-Tau increase, CX3CL1 levels were significantly decreased (26%) in lentiviral expressing P301L hemispheres compared to Tau, but CX3CL1 remained significantly higher (29%) than LacZ. Further quantification of molecular markers of inflammation revealed a significant increase in tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α levels (Fig. 1O) in cortex injected with either Tau (48%) or P301L (51%) compared to LacZ. To determine whether p-Tau and CX3CL1 expression are associated with cell death, we measured the activity of caspase-3 as an apoptotic marker. Caspase-3 activity was significantly increased either when Tau (21%) or P301L (32%) were expressed compared to LacZ injected cortex (Fig. 1P).

Figure 1. CX3CL1 is associated with p-Tau.

Immuno-staining with Tau-5 antibody of 20 µm thick cortical brain sections in lentiviral A) LacZ, and B) Tau injected hemispheres. C) Drawing shows distribution of lentiviral insert expression within 4 mm radius from point on injection in the cortex. Immuno-staining with AT8 antibody of 20 µm thick cortical brain sections in lentiviral D) LacZ, E) Tau and F) P301L injected hemispheres. Immunostaining with CX3CL1 in G) LacZ, H) Tau and I) P301L injected hemispheres. Figures merged to show co-localization in J) LacZ K) Tau and L) P301L injected animals. Histograms represent ELISA measurements showing M) Levels of human p-Tau at Ser 396 in animals injected with Tau, P301L and LacZ. N) Levels of soluble CX3CL1. O) Levels of TNF-α and P) levels of caspase-3 activity. Bars are mean±SD. All experiments were expressed as % control. Asterisks indicate significantly different, P<0.05, ANOVA with Neumann Keuls comparison, N=7 for Tau, N=11 for LacZ and N=4 for P301L.

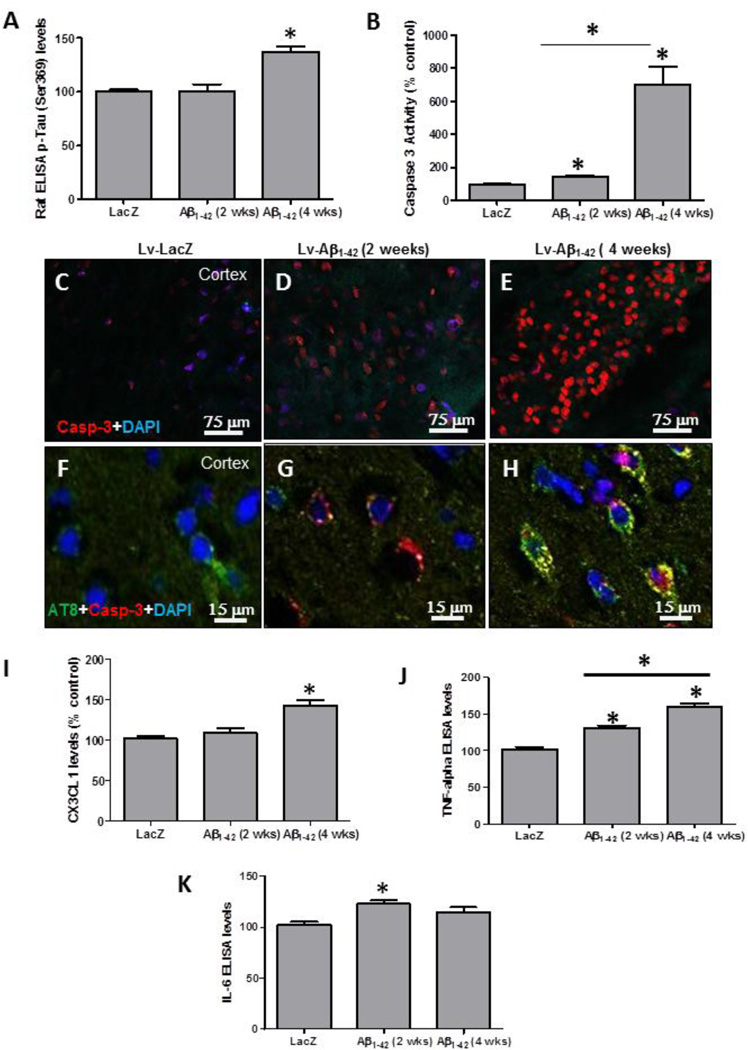

To determine whether p-Tau is linked to CX3CL1 signaling, independent of total Tau levels, we examined cortical brain lysates from hemispheres injected with lentiviral Aβ1–42 (Rebeck, et al., 2010). Lentiviral injection of Aβ1–42 did not result in detectable p-Tau 2 weeks post-injection (Fig. 2A), but an increase (37%) of p-Tau was observed 4 weeks post-injection compared to LacZ (P<0.05, N=8), suggesting that lentiviral Aβ1–42 can be used to seed for p-Tau. We previously did not detect any changes in Ser 396 at 4 weeks post-injection by Western blot (Rebeck, et al., 2010). Caspase-3 activity was also significantly increased (42%) 2 weeks post-injection with lentiviral Aβ1–42 (Fig. 2B) in the absence of p-Tau, but an 8-fold increase was detected at 4 weeks, when both Aβ1–42 and p-Tau were detected. Immunostaining for caspase-3 showed an increase (45% by stereology) 2 weeks postinjection with lentiviral Aβ1–42 (Fig. 2D, P<0.05, N=8) and further increase (680%) was observed 4 weeks post-injection (Fig. 2E) compared to LacZ (Fig. 1C). High magnification images showed caspase-3 staining without appreciable p-Tau at 2 weeks (Fig. 2G) and co-localization of p-Tau (AT8) and caspase-3 at 4 weeks post-injection (Fig. 2H) compared to LacZ (Fig. 2F), indicating that the appearance of p-Tau increases caspase-3 activity in lentiviral Aβ1–42 injected cortex.

Figure 2. Lentiviral Aβ1–42 alters CX3CL1 levels and induces p-Tau.

ELISA measurements of cortical brain lysates showing A) Levels of rat p-Tau at Ser 396 in animals injected with Aβ1–42 and LacZ and B) Levels of caspase-3 activity. Immuno-staining with caspase-3 antibody of 20 µm thick cortical brain sections in lentiviral C) LacZ, D) Aβ1–42 at 2 weeks post-injection and E) Aβ1–42 at 4 weeks post-injection. Co-staining with caspase-3 and AT8 antibodies in lentiviral F) LacZ, G) Aβ1–42 at 2 weeks post-injection and H) Aβ1–42 at 4 weeks post-injection. Histograms represent I) Soluble CX3CL1 and J) TNF-α levels and K) IL-6 levels. Bars are mean±SD. All experiments were expressed as % control. Asterisks indicate significantly different, P<0.05, ANOVA with Neumann Keuls comparison, N=8 for LacZ and Aβ1–42.

Interestingly, no change in CX3CL1 was observed 2 weeks post-injection with Aβ1–42 (Fig. 2I) when p-Tau was not detected compared to LacZ, but a significant increase in CX3CL1 levels (47%) was observed 4 weeks post-injection when p-Tau was present (Fig. 2I). ELISA showed a significant increase (26%) in TNF-α at 2 weeks compared to LacZ (Fig. 2J), but a significantly higher increase (62%) was detected 4 weeks post-injection with lentiviral Aβ1–42. Further examination of other inflammatory markers showed a significant increase (26%) in interleukin (IL)-6 (Fig. 2K) 2 weeks post-injection compared to LacZ, but no changes in IL-6 were detected 4 weeks post-injection.

CX3CL1 increase is associated with alterations of a disintegrin and metalloproteinase domain-containing protein 10/17 (ADAM-10/17) levels

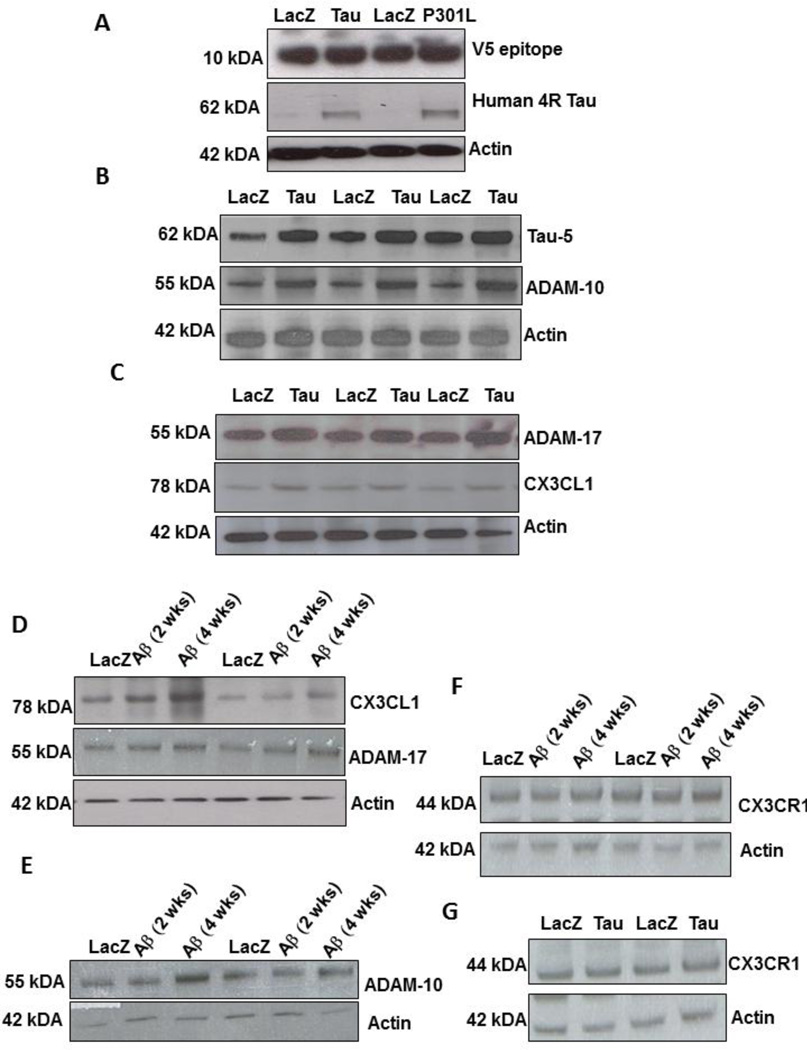

To determine whether the changes in CX3CL1 levels are due to Tau and not to lentiviral expression, we used Western blot analysis and probed for the V5 epitope-tagged lentivirus. The V5 epitope is not fused with Tau, and it is expressed as an indication of lentiviral expression (Khandelwal, et al., 2012). Similar levels of V5 expression were observed in lentiviral LacZ, P301L and Tau injected hemispheres (Fig. 3A, 1st blot) compared to actin levels, indicating expression of the lentivirus within the cortex. We also used a human specific 4R Tau antibody and observed that human Tau was only expressed in Lentiviral Tau but not LacZ injected hemispheres (Fig. 3A, 2nd blot). We pursued an independent approach to determine CX3CL1 levels in cortical brain extracts. Because neuronal CX3CL1 can be cleaved by ADAM-10/17 (Clark, et al., 2009, Garton, et al., 2001), we used Western blot analysis to determine whether enzyme levels are associated with alteration of CX3CL1. Expression of wild type Tau (Fig. 3B, 1st blot) was associated with a significant increase (40%, by densitometry) of ADAM-10 (Fig. 3B, 2nd blot) and ADAM-17 (30%) levels (Fig. 3C, 1st blot) compared to LacZ. A significant increase in CX3CL1 levels (41% by densitometry) was observed in lentiviral Tau expressing cortex compared to LacZ (Fig. 3C, P<0.05, N=7), in agreement with the ELISA results. We further examined CX3CL1 levels in lentiviral Aβ1–42 expressing animals at 2 and 4 weeks post-injection, prior and after p-Tau detection, respectively. We detected a significant increase (36%) in CX3CL1 levels 4 weeks, but not 2 weeks, compared to LacZ (Fig. 3D, 1st blot). Similarly, the increase in CX3CL1 levels was concurrent with elevated expression of both ADAM-17 (Fig. 3D, 2nd blot) and ADAM-10 (Fig. 3E, 2nd blot). No differences in glial CX3CR1 levels were detected either when lentiviral Aβ1–42 (Fig. 3F) or Tau or P301L (Fig. 3G) were expressed.

Figure 3. Tau expression increases ADAM-10/17 and CX3CL1 levels.

Western blot analysis of cortical brain lysates from animals injected with lentiviral LacZ, Tau or P301L on 4–12% SDS-NuPAGE gel showing levels of A) lentiviral V5 epitope (1st blot), human 4R Tau (2nd blot) and actin (3rd blot). B) Total Tau levels (top blot), ADAM-10 (middle blot) and actin (bottom blot). C) ADAM-17 levels (top blot), CX3CL1 (middle blot) and actin (bottom blot). Western blot analysis of cortical brain lysates from animals injected with lentiviral Aβ1–42 and LacZ on 4–12% SDS-NuPAGE gel showing D) CX3CL1 levels (top blot), ADAM-17 (2nd blot) and actin (bottom blot). Western blot on 4–12% SDS-NuPAGE gel showing E) ADAM-10 (1st blot) and actin (bottom blot), CX3CR1 levels in F) Tau injected animals and G) Aβ1–42 injected animals.

Microglia are activated in the absence of an increase of CX3CL1

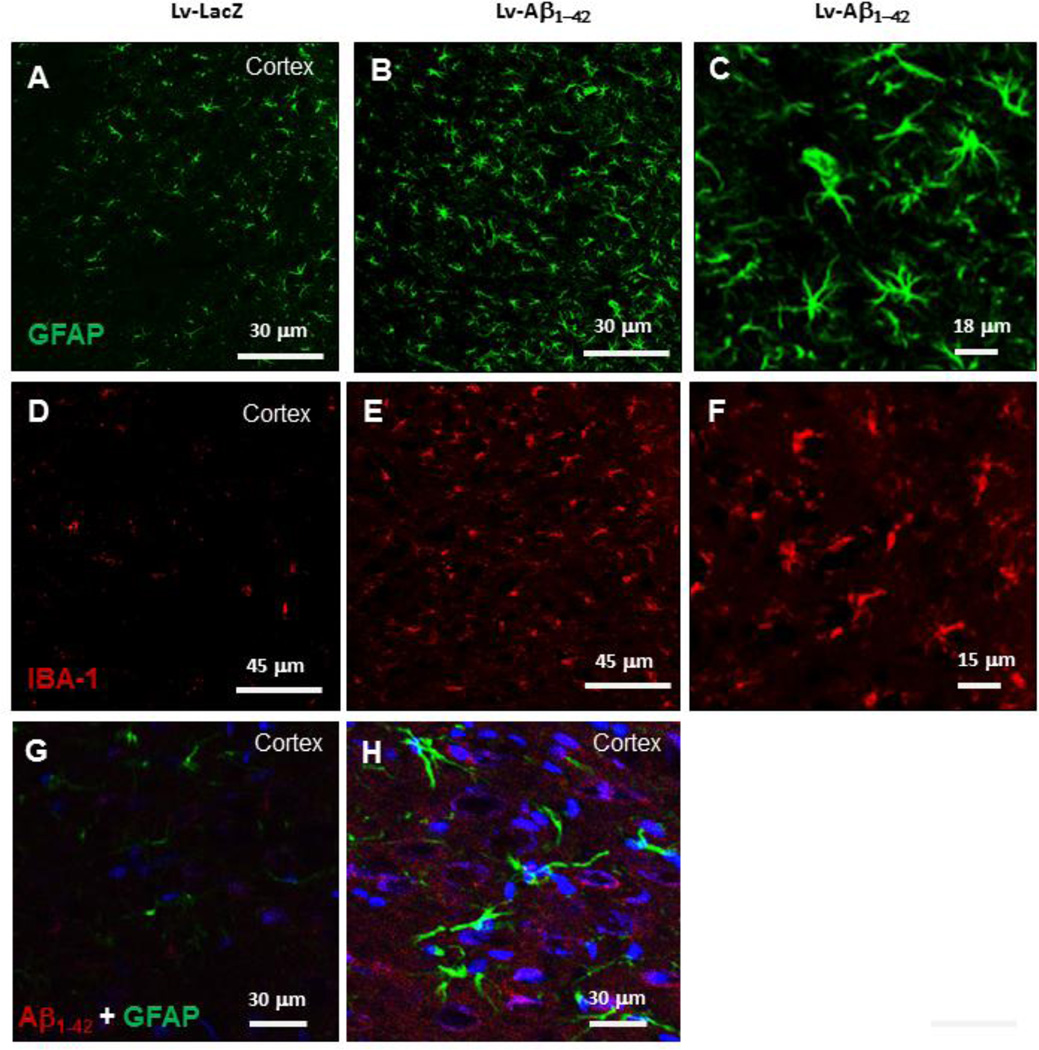

We previously demonstrated an increase in astrocyte but not microglial activity 4 weeks post-injection of lentiviral Aβ1–42 (Rebeck, et al., 2010). Lentiviral Aβ1–42 resulted in Tau modification similar to expression of lentiviral Tau or P301L alone (Khandelwal, et al., 2011). We also detected differential microglial activation in Tau and P301L injected animals (Khandelwal, et al., 2011). Immunohistochemistry showed an increase (P<0.05) in the number of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP)-positive astrocytes (44% by stereology, N=8) at 2 weeks post-injection with lentiviral Aβ1–42 (Fig. 4B) compared to control (Fig. 4A). High magnification images show the morphology of GFAP-positive astrocytes in lentiviral Aβ1–42 injected hemispheres (Fig. 4C). However, a significant increase (70% by stereology, N=8) in the number of ionized calcium binding adaptor molecule (IBA)-I positive microglia (Fig. 4E) was also detected at 2 weeks post-injection with lentiviral Aβ1–42 compared to LacZ injected cortex (Fig. 4D), suggesting a relationship between p-Tau, CX3CL1 and microglial activity. High magnification images show microglial morphology (Fig. 4F) 2 weeks post-injection with lentiviral Aβ1–42. To determine whether astrocyte activity is within the brain regions that express Aβ1–42, we co-stained with anti-GFAP and human Aβ1–42 antibodies. An increase in astrocyte activity and size was detected in cortical regions that show lentiviral expression of Aβ1–42 (Fig. 4H) compared to LacZ (Fig. 4G).

Figure 4. Microglia are activated 2 weeks post-injection with lentiviral Aβ1–42.

Immunostaining with anti-GFAP antibody of 20 µm thick cortical brain sections in lentiviral A) LacZ injected hemispheres, and B) Aβ1–42 injected animals. C) High magnification figure showing morphology of GFAP-positive astrocytes. Immuno-staining with anti-IBA-1 antibody of 20 µm thick cortical sections in lentiviral D) LacZ injected animals, E) Aβ1–42 injected animals and F) High magnification figure showing morphology of IBA-1-positive microglia. Immuno-staining with anti-GFAP (green), anti-Aβ1–42 (red) and nuclear DAPI (blue) of 20 µm thick cortical brain sections in lentiviral G) LacZ and H) Aβ1–42 injected animals.

Tau expression alters normal autophagy

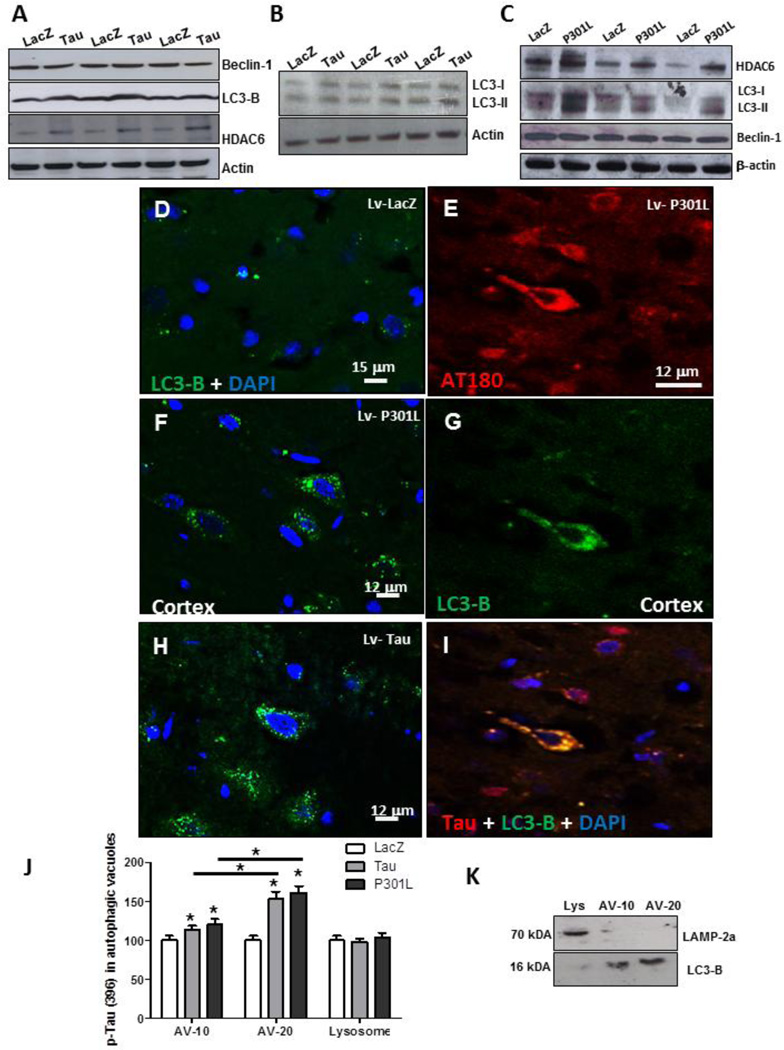

We previously reported pronounced autophagic alterations prior to p-Tau accumulation at 2 weeks post-injection of Aβ1–42 (Lonskaya, et al., 2012). To further evaluate whether accumulation of p-Tau alters autophagy, independent of Aβ1–42 expression, we probed for molecular markers of autophagy using Western blot in lentiviral Tau or P301L expressing hemispheres. No differences were detected in beclin-1 levels between Tau and LacZ injected hemispheres (Fig. 5A). We first determined the levels of microtubule-associated light chain-3 (LC3)-II, using an antibody specific for isoform LC3-B. LC3-I is abundant and stable in the brain, and both the ratio of LC3-II to LC3-I and the amount of LC3-II can be used to monitor the amount of autophagosome (Koike, et al., 2005). LC3 is expressed as three isoforms in mammalian cells, LC3A, LC3B and LC3C (He, et al., 2003), which exhibit different tissue distributions. An increase in LC3-B level was observed in Tau expressing cortex (Fig. 5A, 42% by densitometry) compared to LacZ, suggesting autophagic activity. We also determined the levels of histone deacetylase 6 (HDAC6), which regulates autophagosome-lysosome fusion (autolysosome) via facilitation of movement of organelles along the microtubules (Ding, et al., 2008, Guthrie and Kraemer, 2011, Perez, et al., 2009). A significant increase in HDAC6 level (Fig. 5A, 30% by densitometry) was also detected in Tau compared to LacZ injected hemispheres. To further ascertain changes in LC3 lipidation on Western blot, we probed with anti-LC3 antibody and observed increased levels of both LC3-I and LC3-II (Fig. 5B), but the ratio of LC3-II compared to LC3-I was significantly increased (31% by densitometry) in Tau injected hemispheres, suggesting increased autophagic activity. The changes in autophagic markers in lentiviral P301L expressing cortex were similar, including an increase (51%) in HDAC6 (Fig. 5C, N=4), and increased levels of both LC3-I and LC3-II (Fig. 5C), and the ratio of LC3-II compared to LC3-I (24% by densitometry), while no changes in Beclin-1 were observed compared to LacZ (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5. Autophagic alterations in Tau expressing animals.

Western blot analysis (N=7) of cortical brain lysates from animals injected with lentiviral LacZ and Tau on 4–12% SDS-NuPAGE gel showing A) Beclin-1 levels (top blot), LC3-B (2nd blot), HDAC6 (3rd blot) and actin (bottom blot). Western blot analysis on 4–12% SDS-NuPAGE gel showing B) LC3-I and LC3-II levels (1st blot) compared to actin (bottom blot). C) Western blot analysis on 4–12% SDS-NuPAGE gel showing HDAC6 (1st blot), LC3-I and LC3-II levels (2nd blot) and beclin-1 (3rd blot) compared to actin (bottom blot). Immuno-staining with anti-LC3-B antibody of 20 µm thick cortical sections in lentiviral D) LacZ injected animals (N=8), F) P301L injected animals (N=4) and H) Tau injected animals (N=7). Immuno-staining with E) AT180 antibody and G) anti-LC3-B antibody and I) merge of LC3-B and AT180 of 20 µm thick cortical sections in lentiviral Tau injected animals (N=7). J) Histograms represent ELISA measurements (N=4) showing Levels of human p-Tau at Ser 396 in autophagic vacuoles of animals injected with Tau, P301L and LacZ. K) Western blot analysis on cortical lysates following subcellular fractionation showing LAMP-3 in lysosomal fractions (Top blot) and LC3-B in autophagic vacuoles fractions. Bars are percent mean±SD. All experiments were expressed as % control. Asterisks indicate significantly different, P<0.05, ANOVA with Neumann Keuls comparison. Lv: Lentivirus.

We pursued an independent approach using immunohistochemistry to detect autophagosome formation using LC3-B antibody. Cortical brain sections from animals injected with lentiviral LacZ did not show any noticeable LC3-B staining (Fig. 5D). However, expression of either lentiviral P301L (Fig. 5F) or Tau (Fig. 5H) resulted in LC3-B puncta formation observed at 120x magnification. Stereological counting of LC3-B positive cells revealed a significant increase in lentiviral Tau (28%, N=7) and P301L (32%, N=7) compared to LacZ injected cortex. These data suggest formation of autophagosomes in animals injected with lentiviral Tau or P301L. To further determine whether cells that accumulate p-Tau undergo autophagic changes, we co-stained with AT180 and LC3-B antibodies. Accumulation of p-Tau (Fig. 5E) resulted in LC3-B detection (Fig. 5G) and co-localization within the same cells (Fig. 5I), indicating that cells which accumulate p-Tau also express autophagic markers.

We further examined p-Tau clearance via autophagy using subcellular fractionation and isolation of autophagic compartments. ELISA measurement of p-Tau at Ser396 (Fig. 5J) showed significantly increased (P<0.05) levels of autophagic vacuoles (AV-10), which is enriched in autophagosomes (Marzella, et al., 1982), when animals expressed wild type Tau (14%) and P301L (20%). However, significantly higher levels of p-Tau were detected in AV-20, which is enriched in autolysosomes (Marzella, et al., 1982), when either Tau (53%) or P301L (61%) were expressed compared to LacZ (Fig. 5J). No p-Tau was detected in the lysosomal compartment. To ascertain that fractionation resulted in isolation of autophagosomal from lysosomal fractions, we performed Western blot analysis on the sub-fractions and detected autophagosomal marker LC3-B only in AV-10 and AV- 20, while the lysosomal fraction was only positive for lysosomal marker LAMP-2a (Fig. 5K).

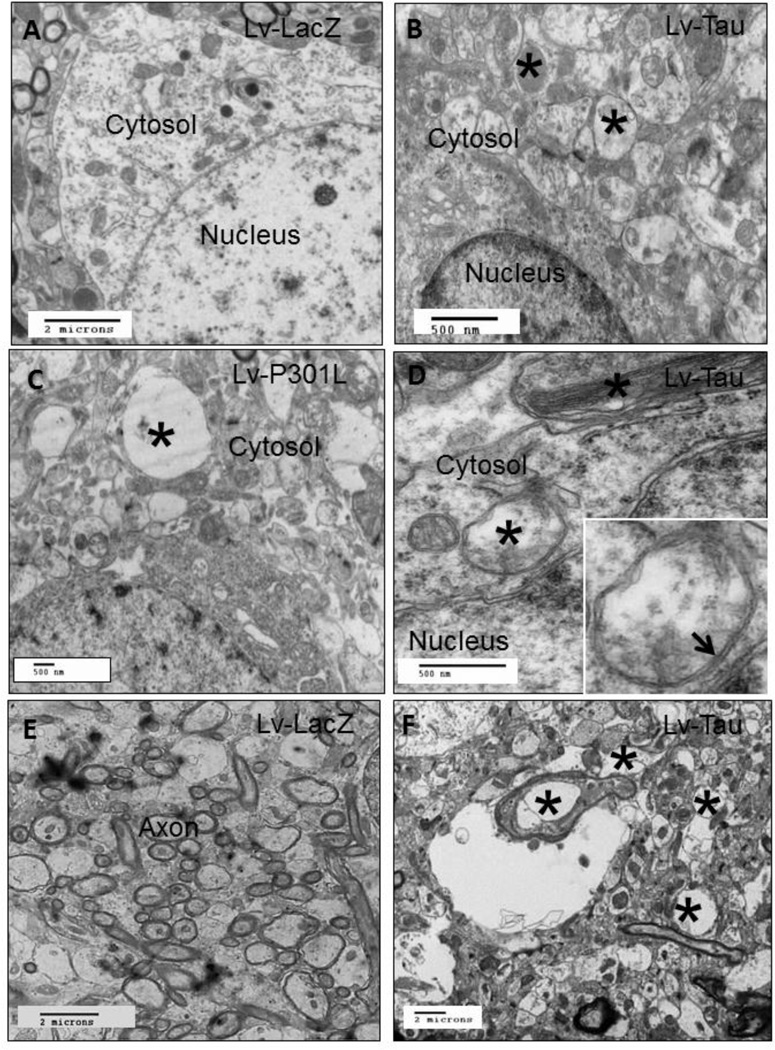

Electron Microscopy reveals accumulation of AVs in Tau expressing cortex

To further assess the overall status of autophagy we performed electron microscopy to detect AVs. Animals injected with lentiviral LacZ showed no AVs in the cytosol (Fig. 6A). Expression of lentiviral Tau resulted in cytosolic accumulation of AVs (Fig. 6B, asterisks) at different stages of maturation (Marzella, et al., 1982). Furthermore, lentiviral P301L expression also resulted in accumulation of AVs (Fig. 6C, asterisk), suggesting lack of autophagic clearance. High magnification images showed fibrillar species (Fig. 6D, asterisk) in Tau expressing hemispheres and the insert shows double membrane AVs indicating autophagosomes. Animals expressing Tau exhibited irregular axonal sizes and signs of axonal degeneration (Fig. 6F, asterisks) manifest in enlarged axonal diameter, compared to LacZ injected animals (Fig. 6E).

Figure 6. Electron microscopy shows accumulation of autophagic vacuoles.

Electron micrographs from the cortex of animals injected with lentiviral A) LacZ show clear cytosol. Lentiviral injection of B) Lentiviral Tau shows accumulation of autophagic vacuoles (asterisks) in the cytosol. Lentiviral injection of C) Lentiviral P301L shows accumulation of autophagic vacuoles (asterisk). Lentiviral injection of D) Lentiviral Tau shows accumulation of fibrillar species (asterisk). Insert is high magnification of autophagic vacuole with double membrane (arrow). EM micrographs showing normal axons in E) LacZ and F) abnormally enlarged axons in Tau expressing animals. Lv: Lentivirus.

Discussion

These studies suggest a possible link between autophagic activity and neuro-inflammation. Changes in autophagy are recognized in a number of neurodegenerative diseases, including AD, PD, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and Huntington’s disease (HD) (Boland, et al., 2008, Kegel, et al., 2000, Nixon, et al., 2005, Ravikumar, et al., 2002, Sabatini, 2006, Stefanis, et al., 2001, Webb, et al., 2003). Activation of autophagy can be detrimental when undigested AVs accumulate. Amyloid precursor protein (APP) accumulates in un-degraded autophagosomes, leading to Aβ leakage and cell death (Yu, et al., 2005) in vitro and in vivo models of AD. Our data suggest that the increase in LC3-II level is an insufficient measure of completion of autophagy, but may reflect induction of autophagy and/or inhibition of autophagosome clearance (Chu, 2006, Klionsky, et al., 2008), leading to p-Tau accumulation in un-digested AVs. Recent reports suggest that generation of autophagosomes is induced distally at neurite tips and its maturation depends on intact transport along axonal microtubules toward the soma (Maday, et al., 2012). In the current studies, p-Tau accumulation may have destabilized microtubules, leading to lack of recognition and/or fusion between p-Tau containing AVs and digestive lysosomes. Post-translational modification facilitates the recognition between autophagic compartments (Kirkin, et al., 2009, Sarkar, et al., 2009), and brings the target to form autophagosome through interaction with LC3 (Bjorkoy, et al., 2005, Tan, et al., 2007). Inefficient recognition among AVs may happen (Klionsky, et al., 2008, Wong, et al., 2008), whereby the molecular steps of autophagy are activated but autophagosome clearance is inefficient (He and Klionsky, 2009). Therefore, the completion of autophagy through initiation and clearance of autophagosomes are indispensable for p- Tau removal.

We previously showed that accumulation of p-Tau is associated with increased levels of inflammatory markers including TNF-α and IL-6 as well as increased microglial activity in lentiviral Tau expressing animals (Khandelwal, et al., 2011). Here we show that CX3CL1 levels and p-Tau are increased in Tau expressing animals, when IL-6 was not significantly different than LacZ, as we previously showed (Khandelwal, et al., 2011). Additionally, CX3CL1 levels are significantly decreased in P301L animals accumulating higher levels of p-Tau, with no observable difference in IL-6 (Khandelwal, et al., 2011). In agreement with these findings, no changes in CX3CL1 and p-Tau levels were detected with an increase in IL-6, but both CX3CL1 and p-Tau are elevated, with no change in IL- 6 after p-Tau seeding with Aβ1–42. These data suggest that CX3CL1 may interact with IL-6 to modulate the inflammatory response since CX3CL1 inhibits production of Nitric oxide, IL-6, and TNF-α (Limatola, et al., 2005, Zujovic, et al., 2000). Further longitudinal studies are needed to delineate the interaction between CX3CL1 and IL-6 and determine whether modulation of these inflammatory markers can regulate microglial activity in different stages of disease progression.

Activated microglia are found in postmortem brain tissues of human patients with Tauopathy (Gebicke-Haerter, 2001, Gerhard, et al., 2006, Ishizawa and Dickson, 2001); and here we show that soluble CX3CL1 is associated with the appearance of p-Tau in lentiviral gene transfer animals. However, lack of p-Tau detection was not associated with changes in CX3CL1 in lentiviral Aβ1–42 expressing animals, suggesting that CX3CL1 levels may critically dependent on the stage of disease pathology. Plasma levels of CX3CL1 are significantly increased in early stages of AD and decreased in severe AD (Kim, et al., 2008). CX3CL1 levels are decreased in the hippocampus and frontal cortex of advanced stages of AD (Cho, et al., 2011), suggesting variable roles of CX3CL1 in different stages of AD pathogenesis. Furthermore, CX3CL1 levels are decreased by Aβ (Cho, et al., 2011), and our data show no changes in CX3CL1 at 2 weeks in Aβ1–42 animals undergoing autophagy (Lonskaya, et al., 2012), but detection of p-Tau is associated with alterations of CX3CL1 levels. In animals overexpressing wild type Tau, p-Tau is associated with increased levels of CX3CL1, while further increases of p-Tau in P301L expressing animals result in decreased CX3CL1 levels. These findings highlight the complexity of microglial activation and suggest a link between CX3CL1 and p-Tau, leading to either toxic or protective outcomes. Understanding the underlying signaling pathways between p-Tau and microglia will have important implications in AD and other neurodegenerative diseases and may affect anti-inflammatory treatment paradigms at different stages of disease progression.

CX3CL1 is expressed in neurons as a full-length trans-membrane protein, but it can be cleaved by TNF-α-converting enzyme (TACE/ADAM-17, ADAM-10) or cathepsin S (Clark, et al., 2009, Garton, et al., 2001) and released in a soluble form that exclusively binds microglial CX3CR1 (Harrison, et al., 1998, Imai, et al., 1997). Several findings suggest that deletion of CX3CR1 increases microglial activity in various models of acute and chronic neuronal injury (Bhaskar, et al., 2010, Cardona, et al., 2008, Cho, et al., 2011, Liu, et al., 2010), while other studies show that deletion of CX3CR1 decreases microglial activity (Fuhrmann, et al., 2010). Deletion of CX3CR1 aggravates microglial neurotoxicity in response to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in the 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) model of PD and in the SOD1G93A model of ALS (Cardona, et al., 2006). Although CX3CR1 effects on microglia may decrease Aβ deposition (Bhaskar, et al., 2010, Cho, et al., 2011, Liu, et al., 2010), CX3CR1 deficiency exacerbates neuronal AD-related pathologies, including p-Tau (Bhaskar, et al., 2010, Cho, et al., 2011). CX3CR1 deficiency in Tau transgenic mice accelerates p-Tau and leads to behavioral deficits (Bhaskar, et al., 2010). Some studies show that CX3CL1 suppresses neuronal cell death caused by activated microglia (Mizuno, et al., 2003), and other studies indicate that CX3CR1 deletion prevents neuronal loss caused by microglial migration independent of Aβ accumulation in triple transgenic AD mice (Fuhrmann, et al., 2010). Taken together, these findings suggest that CX3CL1 regulates microglial activity and may be beneficial in Aβ clearance (Bhaskar, et al., 2010, Cho, et al., 2011, Liu, et al., 2010), however, the role of CX3CL1 is detrimental to p-Tau (Cho, et al., 2011, Harrison, et al., 1998, Liu, et al., 2010). Therefore, our approach to induce p-Tau using Tau overexpression or seeding with Aβ1–42 is beneficial to determine whether p-Tau depends on total Tau levels or altered interaction between neurons and microglia.

The present studies provide some clues about a relationship between p-Tau, autophagy and neuro-inflammation. It is possible that neurons accumulating pathogenic proteins stimulate autophagy, causing an increase in cleavage enzymes to release soluble CX3CL1, which is increased in the plasma of early stage AD patients (Kim, et al., 2008), and correlates positively with disease severity and progression in human PD patients (Shi, et al., 2011). However, disease progression and apoptotic neuronal death may decrease the availability of CX3CL1, activating microglia to promote neuronal p- Tau as a tag for phagocytic degradation in late stages of disease (Cho, et al., 2011, Kim, et al., 2008). A longitudinal approach to monitor neuronal autophagy, CX3CL1 levels, microglial activation and p-Tau is needed. Finally, autophagic defects and neuro-inflammation are well recognized in association with p-Tau and Aβ accumulation in AD. These studies attempt to better understand the relationship between seemingly co-existing phenomena in AD pathology, including modulation of the inflammatory response via CX3CL1 signaling and alteration of normal autophagic mechanisms.

Highlights.

p-Tau leads to inflammation and increased levels of ADAM-10/17

Seeding for p-Tau with lentiviral Aβ1–42 produces neuro-inflammation

Microglial activity is associated with CX3CL1 and p-Tau

Autophagic changes are associated with neuro-inflammation

p-Tau accumulates within autophagic vacuoles not lysosomes

Acknowledgments

These studies are supported by NIH AG30378 and Georgetown University funds to Charbel Moussa. The authors would like to thank Dr. James Driver at the University of Montana for his assistance in the EM studies.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of interests: The authors declare no competing or conflict of interests, financial or other, in association with this manuscript.

References

- 1.Bazan JF, Bacon KB, Hardiman G, Wang W, Soo K, Rossi D, Greaves DR, Zlotnik A, Schall TJ. A new class of membrane-bound chemokine with a CX3C motif. Nature. 1997;385:640–644. doi: 10.1038/385640a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhaskar K, Konerth M, Kokiko-Cochran ON, Cardona A, Ransohoff RM, Lamb BT. Regulation of tau pathology by the microglial fractalkine receptor. Neuron. 2010;68:19–31. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bird TD, Nochlin D, Poorkaj P, Cherrier M, Kaye J, Payami H, Peskind E, Lampe TH, Nemens E, Boyer PJ, Schellenberg GD. A clinical pathological comparison of three families with frontotemporal dementia and identical mutations in the tau gene (P301L) Brain. 1999;122(Pt 4):741–756. doi: 10.1093/brain/122.4.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bjorkoy G, Lamark T, Brech A, Outzen H, Perander M, Overvatn A, Stenmark H, Johansen T. p62/SQSTM1 forms protein aggregates degraded by autophagy and has a protective effect on huntingtin-induced cell death. J Cell Biol. 2005;171:603–614. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200507002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boland B, Kumar A, Lee S, Platt FM, Wegiel J, Yu WH, Nixon RA. Autophagy induction and autophagosome clearance in neurons: relationship to autophagic pathology in Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 2008;28:6926–6937. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0800-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;82:239–259. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burns MP, Zhang L, Rebeck GW, Querfurth HW, Moussa CE. Parkin promotes intracellular Abeta1-42 clearance. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:3206–3216. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cameron B, Landreth GE. Inflammation, microglia, and Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2010;37:503–509. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cardona AE, Pioro EP, Sasse ME, Kostenko V, Cardona SM, Dijkstra IM, Huang D, Kidd G, Dombrowski S, Dutta R, Lee JC, Cook DN, Jung S, Lira SA, Littman DR, Ransohoff RM. Control of microglial neurotoxicity by the fractalkine receptor. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:917–924. doi: 10.1038/nn1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cardona AE, Sasse ME, Liu L, Cardona SM, Mizutani M, Savarin C, Hu T, Ransohoff RM. Scavenging roles of chemokine receptors: chemokine receptor deficiency is associated with increased levels of ligand in circulation and tissues. Blood. 2008;112:256–263. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-118497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cho SH, Sun B, Zhou Y, Kauppinen TM, Halabisky B, Wes P, Ransohoff RM, Gan L. CX3CR1 protein signaling modulates microglial activation and protects against plaque-independent cognitive deficits in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:32713–32722. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.254268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chu CT. Autophagic stress in neuronal injury and disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2006;65:423–432. doi: 10.1097/01.jnen.0000229233.75253.be. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clark AK, Yip PK, Malcangio M. The liberation of fractalkine in the dorsal horn requires microglial cathepsin S. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:6945–6954. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0828-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Combadiere C, Feumi C, Raoul W, Keller N, Rodero M, Pezard A, Lavalette S, Houssier M, Jonet L, Picard E, Debre P, Sirinyan M, Deterre P, Ferroukhi T, Cohen SY, Chauvaud D, Jeanny JC, Chemtob S, Behar-Cohen F, Sennlaub F. CX3CR1-dependent subretinal microglia cell accumulation is associated with cardinal features of age-related macular degeneration. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2920–2928. doi: 10.1172/JCI31692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dawson HN, Cantillana V, Jansen M, Wang H, Vitek MP, Wilcock DM, Lynch JR, Laskowitz DT. Loss of tau elicits axonal degeneration in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Neuroscience. 2010;169:516–531. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.04.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dawson HN, Ferreira A, Eyster MV, Ghoshal N, Binder LI, Vitek MP. Inhibition of neuronal maturation in primary hippocampal neurons from tau deficient mice. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:1179–1187. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.6.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ding H, Dolan PJ, Johnson GV. Histone deacetylase 6 interacts with the microtubuleassociated protein tau. J Neurochem. 2008;106:2119–2130. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05564.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dolan PJ, Johnson GV. A caspase cleaved form of tau is preferentially degraded through the autophagy pathway. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:21978–21987. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.110940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frank-Cannon TC, Alto LT, McAlpine FE, Tansey MG. Does neuroinflammation fan the flame in neurodegenerative diseases? Mol Neurodegener. 2009;4:47. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-4-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fuhrmann M, Bittner T, Jung CK, Burgold S, Page RM, Mitteregger G, Haass C, LaFerla FM, Kretzschmar H, Herms J. Microglial Cx3cr1 knockout prevents neuron loss in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:411–413. doi: 10.1038/nn.2511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garton KJ, Gough PJ, Blobel CP, Murphy G, Greaves DR, Dempsey PJ, Raines EW. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha-converting enzyme (ADAM17) mediates the cleavage and shedding of fractalkine (CX3CL1) J Biol Chem. 2001;276:37993–38001. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106434200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gasparini L, Terni B, Spillantini MG. Frontotemporal dementia with tau pathology. Neurodegener Dis. 2007;4:236–253. doi: 10.1159/000101848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gebicke-Haerter PJ. Microglia in neurodegeneration: molecular aspects. Microsc Res Tech. 2001;54:47–58. doi: 10.1002/jemt.1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gerhard A, Pavese N, Hotton G, Turkheimer F, Es M, Hammers A, Eggert K, Oertel W, Banati RB, Brooks DJ. In vivo imaging of microglial activation with [11C](R)-PK11195 PET in idiopathic Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2006;21:404–412. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gomez-Isla T, Hollister R, West H, Mui S, Growdon JH, Petersen RC, Parisi JE, Hyman BT. Neuronal loss correlates with but exceeds neurofibrillary tangles in Alzheimer's disease. Ann Neurol. 1997;41:17–24. doi: 10.1002/ana.410410106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K, Tung YC, Quinlan M, Wisniewski HM, Binder LI. Abnormal phosphorylation of the microtubule-associated protein tau (tau) in Alzheimer cytoskeletal pathology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:4913–4917. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.13.4913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guthrie CR, Kraemer BC. Proteasome inhibition drives HDAC6-dependent recruitment of tau to aggresomes. J Mol Neurosci. 2011;45:32–41. doi: 10.1007/s12031-011-9502-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harada A, Oguchi K, Okabe S, Kuno J, Terada S, Ohshima T, Sato-Yoshitake R, Takei Y, Noda T, Hirokawa N. Altered microtubule organization in small-calibre axons of mice lacking tau protein. Nature. 1994;369:488–491. doi: 10.1038/369488a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hardy J, Allsop D. Amyloid deposition as the central event in the aetiology of Alzheimer's disease. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1991;12:383–388. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(91)90609-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hardy JA, Higgins GA. Alzheimer's disease: the amyloid cascade hypothesis. Science. 1992;256:184–185. doi: 10.1126/science.1566067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harrison JK, Jiang Y, Chen S, Xia Y, Maciejewski D, McNamara RK, Streit WJ, Salafranca MN, Adhikari S, Thompson DA, Botti P, Bacon KB, Feng L. Role for neuronally derived fractalkine in mediating interactions between neurons and CX3CR1-expressing microglia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:10896–10901. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hasegawa M, Smith MJ, Goedert M. Tau proteins with FTDP-17 mutations have a reduced ability to promote microtubule assembly. FEBS Lett. 1998;437:207–210. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01217-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hatori K, Nagai A, Heisel R, Ryu JK, Kim SU. Fractalkine and fractalkine receptors in human neurons and glial cells. J Neurosci Res. 2002;69:418–426. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.He C, Klionsky DJ. Regulation mechanisms and signaling pathways of autophagy. Annu Rev Genet. 2009;43:67–93. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102808-114910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.He H, Dang Y, Dai F, Guo Z, Wu J, She X, Pei Y, Chen Y, Ling W, Wu C, Zhao S, Liu JO, Yu L. Post-translational modifications of three members of the human MAP1LC3 family and detection of a novel type of modification for MAP1LC3B. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:29278–29287. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303800200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hutton M, Lendon CL, Rizzu P, Baker M, Froelich S, Houlden H, Pickering-Brown S, Chakraverty S, Isaacs A, Grover A, Hackett J, Adamson J, Lincoln S, Dickson D, Davies P, Petersen RC, Stevens M, de Graaff E, Wauters E, van Baren J, Hillebrand M, Joosse M, Kwon JM, Nowotny P, Che LK, Norton J, Morris JC, Reed LA, Trojanowski J, Basun H, Lannfelt L, Neystat M, Fahn S, Dark F, Tannenberg T, Dodd PR, Hayward N, Kwok JB, Schofield PR, Andreadis A, Snowden J, Craufurd D, Neary D, Owen F, Oostra BA, Hardy J, Goate A, van Swieten J, Mann D, Lynch T, Heutink P. Association of missense and 5'-splice-site mutations in tau with the inherited dementia FTDP-17. Nature. 1998;393:702–705. doi: 10.1038/31508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Imai T, Hieshima K, Haskell C, Baba M, Nagira M, Nishimura M, Kakizaki M, Takagi S, Nomiyama H, Schall TJ, Yoshie O. Identification and molecular characterization of fractalkine receptor CX3CR1, which mediates both leukocyte migration and adhesion. Cell. 1997;91:521–530. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80438-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ishizawa K, Dickson DW. Microglial activation parallels system degeneration in progressive supranuclear palsy and corticobasal degeneration. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2001;60:647–657. doi: 10.1093/jnen/60.6.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jiang Z, Tang H, Havlioglu N, Zhang X, Stamm S, Yan R, Wu JY. Mutations in tau gene exon 10 associated with FTDP-17 alter the activity of an exonic splicing enhancer to interact with Tra2 beta. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:18997–19007. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301800200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jimenez-Mateos EM, Gonzalez-Billault C, Dawson HN, Vitek MP, Avila J. Role of MAP1B in axonal retrograde transport of mitochondria. Biochem J. 2006;397:53–59. doi: 10.1042/BJ20060205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kastenbauer S, Koedel U, Wick M, Kieseier BC, Hartung HP, Pfister HW. CSF and serum levels of soluble fractalkine (CX3CL1) in inflammatory diseases of the nervous system. J Neuroimmunol. 2003;137:210–217. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(03)00085-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kegel KB, Kim M, Sapp E, McIntyre C, Castano JG, Aronin N, DiFiglia M. Huntingtin expression stimulates endosomal-lysosomal activity, endosome tubulation, and autophagy. J Neurosci. 2000;20:7268–7278. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-19-07268.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Khandelwal PJ, Dumanis SB, Herman AM, Rebeck GW, Moussa CE. Wild type and P301L mutant Tau promote neuro-inflammation and alpha-Synuclein accumulation in lentiviral gene delivery models. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khandelwal PJ, Dumanis SB, Herman AM, Rebeck GW, Moussa CE. Wild type and P301L mutant Tau promote neuro-inflammation and alpha-Synuclein accumulation in lentiviral gene delivery models. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2012;49:44–53. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim TS, Lim HK, Lee JY, Kim DJ, Park S, Lee C, Lee CU. Changes in the levels of plasma soluble fractalkine in patients with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. Neurosci Lett. 2008;436:196–200. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kirkin V, McEwan DG, Novak I, Dikic I. A role for ubiquitin in selective autophagy. Mol Cell. 2009;34:259–269. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Klionsky DJ, Abeliovich H, Agostinis P, Agrawal DK, Aliev G, Askew DS, Baba M, Baehrecke EH, Bahr BA, Ballabio A, Bamber BA, Bassham DC, Bergamini E, Bi X, Biard-Piechaczyk M, Blum JS, Bredesen DE, Brodsky JL, Brumell JH, Brunk UT, Bursch W, Camougrand N, Cebollero E, Cecconi F, Chen Y, Chin LS, Choi A, Chu CT, Chung J, Clarke PG, Clark RS, Clarke SG, Clave C, Cleveland JL, Codogno P, Colombo MI, Coto-Montes A, Cregg JM, Cuervo AM, Debnath J, Demarchi F, Dennis PB, Dennis PA, Deretic V, Devenish RJ, Di Sano F, Dice JF, Difiglia M, Dinesh-Kumar S, Distelhorst CW, Djavaheri-Mergny M, Dorsey FC, Droge W, Dron M, Dunn WA, Jr, Duszenko M, Eissa NT, Elazar Z, Esclatine A, Eskelinen EL, Fesus L, Finley KD, Fuentes JM, Fueyo J, Fujisaki K, Galliot B, Gao FB, Gewirtz DA, Gibson SB, Gohla A, Goldberg AL, Gonzalez R, Gonzalez-Estevez C, Gorski S, Gottlieb RA, Haussinger D, He YW, Heidenreich K, Hill JA, Hoyer-Hansen M, Hu X, Huang WP, Iwasaki A, Jaattela M, Jackson WT, Jiang X, Jin S, Johansen T, Jung JU, Kadowaki M, Kang C, Kelekar A, Kessel DH, Kiel JA, Kim HP, Kimchi A, Kinsella TJ, Kiselyov K, Kitamoto K, Knecht E, Komatsu M, Kominami E, Kondo S, Kovacs AL, Kroemer G, Kuan CY, Kumar R, Kundu M, Landry J, Laporte M, Le W, Lei HY, Lenardo MJ, Levine B, Lieberman A, Lim KL, Lin FC, Liou W, Liu LF, Lopez-Berestein G, Lopez-Otin C, Lu B, Macleod KF, Malorni W, Martinet W, Matsuoka K, Mautner J, Meijer AJ, Melendez A, Michels P, Miotto G, Mistiaen WP, Mizushima N, Mograbi B, Monastyrska I, Moore MN, Moreira PI, Moriyasu Y, Motyl T, Munz C, Murphy LO, Naqvi NI, Neufeld TP, Nishino I, Nixon RA, Noda T, Nurnberg B, Ogawa M, Oleinick NL, Olsen LJ, Ozpolat B, Paglin S, Palmer GE, Papassideri I, Parkes M, Perlmutter DH, Perry G, Piacentini M, Pinkas-Kramarski R, Prescott M, Proikas-Cezanne T, Raben N, Rami A, Reggiori F, Rohrer B, Rubinsztein DC, Ryan KM, Sadoshima J, Sakagami H, Sakai Y, Sandri M, Sasakawa C, Sass M, Schneider C, Seglen PO, Seleverstov O, Settleman J, Shacka JJ, Shapiro IM, Sibirny A, Silva-Zacarin EC, Simon HU, Simone C, Simonsen A, Smith MA, Spanel-Borowski K, Srinivas V, Steeves M, Stenmark H, Stromhaug PE, Subauste CS, Sugimoto S, Sulzer D, Suzuki T, Swanson MS, Tabas I, Takeshita F, Talbot NJ, Talloczy Z, Tanaka K, Tanida I, Taylor GS, Taylor JP, Terman A, Tettamanti G, Thompson CB, Thumm M, Tolkovsky AM, Tooze SA, Truant R, Tumanovska LV, Uchiyama Y, Ueno T, Uzcategui NL, van der Klei I, Vaquero EC, Vellai T, Vogel MW, Wang HG, Webster P, Wiley JW, Xi Z, Xiao G, Yahalom J, Yang JM, Yap G, Yin XM, Yoshimori T, Yu L, Yue Z, Yuzaki M, Zabirnyk O, Zheng X, Zhu X, Deter RL. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy in higher eukaryotes. Autophagy. 2008;4:151–175. doi: 10.4161/auto.5338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Koike M, Shibata M, Waguri S, Yoshimura K, Tanida I, Kominami E, Gotow T, Peters C, von Figura K, Mizushima N, Saftig P, Uchiyama Y. Participation of autophagy in storage of lysosomes in neurons from mouse models of neuronal ceroid-lipofuscinoses (Batten disease) Am J Pathol. 2005;167:1713–1728. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61253-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee J, Kim HR, Quinley C, Kim J, Gonzalez-Navajas J, Xavier R, Raz E. Autophagy suppresses interleukin-1beta (IL-1beta) signaling by activation of p62 degradation via lysosomal and proteasomal pathways. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:4033–4040. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.280065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Levine B, Mizushima N, Virgin HW. Autophagy in immunity and inflammation. Nature. 2011;469:323–335. doi: 10.1038/nature09782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Limatola C, Lauro C, Catalano M, Ciotti MT, Bertollini C, Di Angelantonio S, Ragozzino D, Eusebi F. Chemokine CX3CL1 protects rat hippocampal neurons against glutamate-mediated excitotoxicity. J Neuroimmunol. 2005;166:19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2005.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lindwall G, Cole RD. Phosphorylation affects the ability of tau protein to promote microtubule assembly. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:5301–5305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu Z, Condello C, Schain A, Harb R, Grutzendler J. CX3CR1 in microglia regulates brain amyloid deposition through selective protofibrillar amyloid-beta phagocytosis. J Neurosci. 2010;30:17091–17101. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4403-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lonskaya I, Shekoyan AR, Hebron ML, Desforges N, Algarzae NK, Moussa CE. Diminished Parkin Solubility and Co-Localization with Intraneuronal Amyloid-beta are Associated with Autophagic Defects in Alzheimer's Disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012 doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-121141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Maday S, Wallace KE, Holzbaur EL. Autophagosomes initiate distally and mature during transport toward the cell soma in primary neurons. J Cell Biol. 2012 doi: 10.1083/jcb.201106120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Marzella L, Ahlberg J, Glaumann H. Isolation of autophagic vacuoles from rat liver: morphological and biochemical characterization. J Cell Biol. 1982;93:144–154. doi: 10.1083/jcb.93.1.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mirra SS, Murrell JR, Gearing M, Spillantini MG, Goedert M, Crowther RA, Levey AI, Jones R, Green J, Shoffner JM, Wainer BH, Schmidt ML, Trojanowski JQ, Ghetti B. Tau pathology in a family with dementia and a P301L mutation in tau. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1999;58:335–345. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199904000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mizuno T, Kawanokuchi J, Numata K, Suzumura A. Production and neuroprotective functions of fractalkine in the central nervous system. Brain Res. 2003;979:65–70. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02867-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nixon RA, Wegiel J, Kumar A, Yu WH, Peterhoff C, Cataldo A, Cuervo AM. Extensive involvement of autophagy in Alzheimer disease: an immuno-electron microscopy study. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2005;64:113–122. doi: 10.1093/jnen/64.2.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Perez M, Santa-Maria I, Gomez de Barreda E, Zhu X, Cuadros R, Cabrero JR, Sanchez-Madrid F, Dawson HN, Vitek MP, Perry G, Smith MA, Avila J. Tau--an inhibitor of deacetylase HDAC6 function. J Neurochem. 2009;109:1756–1766. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Poorkaj P, Bird TD, Wijsman E, Nemens E, Garruto RM, Anderson L, Andreadis A, Wiederholt WC, Raskind M, Schellenberg GD. Tau is a candidate gene for chromosome 17 frontotemporal dementia. Ann Neurol. 1998;43:815–825. doi: 10.1002/ana.410430617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rancan M, Bye N, Otto VI, Trentz O, Kossmann T, Frentzel S, Morganti-Kossmann MC. The chemokine fractalkine in patients with severe traumatic brain injury and a mouse model of closed head injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2004;24:1110–1118. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000133470.91843.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ransohoff RM, Perry VH. Microglial physiology: unique stimuli, specialized responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:119–145. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ravikumar B, Duden R, Rubinsztein DC. Aggregate-prone proteins with polyglutamine and polyalanine expansions are degraded by autophagy. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:1107–1117. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.9.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rebeck GW, Hoe HS, Moussa CE. Beta-amyloid1-42 gene transfer model exhibits intraneuronal amyloid, gliosis, tau phosphorylation, and neuronal loss. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:7440–7446. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.083915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rogers J, Webster S, Lue LF, Brachova L, Civin WH, Emmerling M, Shivers B, Walker D, McGeer P. Inflammation and Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis. Neurobiol Aging. 1996;17:681–686. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(96)00115-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sabatini DM. mTOR and cancer: insights into a complex relationship. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:729–734. doi: 10.1038/nrc1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Saitoh T, Akira S. Regulation of innate immune responses by autophagy-related proteins. J Cell Biol. 2010;189:925–935. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201002021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sarkar S, Ravikumar B, Rubinsztein DC. Autophagic clearance of aggregate-prone proteins associated with neurodegeneration. Methods Enzymol. 2009;453:83–110. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)04005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shi M, Bradner J, Hancock AM, Chung KA, Quinn JF, Peskind ER, Galasko D, Jankovic J, Zabetian CP, Kim HM, Leverenz JB, Montine TJ, Ginghina C, Kang UJ, Cain KC, Wang Y, Aasly J, Goldstein D, Zhang J. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers for Parkinson disease diagnosis and progression. Ann Neurol. 2011;69:570–580. doi: 10.1002/ana.22311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sporer B, Kastenbauer S, Koedel U, Arendt G, Pfister HW. Increased intrathecal release of soluble fractalkine in HIV-infected patients. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2003;19:111–116. doi: 10.1089/088922203762688612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Stefanis L, Larsen KE, Rideout HJ, Sulzer D, Greene LA. Expression of A53T mutant but not wild-type alpha-synuclein in PC12 cells induces alterations of the ubiquitin-dependent degradation system, loss of dopamine release, and autophagic cell death. J Neurosci. 2001;21:9549–9560. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-24-09549.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tan JM, Wong ES, Dawson VL, Dawson TM, Lim KL. Lysine 63-linked polyubiquitin potentially partners with p62 to promote the clearance of protein inclusions by autophagy. Autophagy. 2007:4. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tobin JE, Latourelle JC, Lew MF, Klein C, Suchowersky O, Shill HA, Golbe LI, Mark MH, Growdon JH, Wooten GF, Racette BA, Perlmutter JS, Watts R, Guttman M, Baker KB, Goldwurm S, Pezzoli G, Singer C, Saint-Hilaire MH, Hendricks AE, Williamson S, Nagle MW, Wilk JB, Massood T, Laramie JM, DeStefano AL, Litvan I, Nicholson G, Corbett A, Isaacson S, Burn DJ, Chinnery PF, Pramstaller PP, Sherman S, Al-hinti J, Drasby E, Nance M, Moller AT, Ostergaard K, Roxburgh R, Snow B, Slevin JT, Cambi F, Gusella JF, Myers RH. Haplotypes and gene expression implicate the MAPT region for Parkinson disease: the GenePD Study. Neurology. 2008;71:28–34. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000304051.01650.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tong N, Perry SW, Zhang Q, James HJ, Guo H, Brooks A, Bal H, Kinnear SA, Fine S, Epstein LG, Dairaghi D, Schall TJ, Gendelman HE, Dewhurst S, Sharer LR, Gelbard HA. Neuronal fractalkine expression in HIV-1 encephalitis: roles for macrophage recruitment and neuroprotection in the central nervous system. J Immunol. 2000;164:1333–1339. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.3.1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wang Y, Martinez-Vicente M, Kruger U, Kaushik S, Wong E, Mandelkow EM, Cuervo AM, Mandelkow E. Synergy and antagonism of macroautophagy and chaperone-mediated autophagy in a cell model of pathological tau aggregation. Autophagy. 2010;6:182–183. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.1.10815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Webb JL, Ravikumar B, Atkins J, Skepper JN, Rubinsztein DC. Alpha-Synuclein is degraded by both autophagy and the proteasome. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:25009–25013. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300227200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wong ES, Tan JM, Soong WE, Hussein K, Nukina N, Dawson VL, Dawson TM, Cuervo AM, Lim KL. Autophagy-mediated clearance of aggresomes is not a universal phenomenon. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:2570–2582. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wyss-Coray T, Mucke L. Inflammation in neurodegenerative disease--a double-edged sword. Neuron. 2002;35:419–432. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00794-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yu WH, Cuervo AM, Kumar A, Peterhoff CM, Schmidt SD, Lee JH, Mohan PS, Mercken M, Farmery MR, Tjernberg LO, Jiang Y, Duff K, Uchiyama Y, Naslund J, Mathews PM, Cataldo AM, Nixon RA. Macroautophagy--a novel Beta-amyloid peptide-generating pathway activated in Alzheimer's disease. J Cell Biol. 2005;171:87–98. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200505082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zujovic V, Benavides J, Vige X, Carter C, Taupin V. Fractalkine modulates TNF-alpha secretion and neurotoxicity induced by microglial activation. Glia. 2000;29:305–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]