Abstract

Objectives

Early identification of bipolar disorder (BP) symptomatology is crucial for improving the prognosis of this illness. Increased mood lability has been reported in BP. However, mood lability is ubiquitous across psychiatric disorders and may be a marker of severe psychopathology and not specific to BP. To clarify this issue, this study examined the prevalence of mood lability and its components in offspring of BP parents and offspring of community control parents recruited through the Pittsburgh Bipolar Offspring Study.

Methods

Forty-one school-age BP offspring of 38 BP parents, 257 healthy or non-BP offspring of 174 BP parents, and 192 offspring of 117 control parents completed a scale that was developed to evaluate mood lability in youth, i.e., the Children’s Affective Lability Scale (CALS).

Results

A factor analysis of the parental CALS, and in part the child CALS, revealed Irritability, Mania, and Anxiety/Depression factors, with most of the variance explained by the Irritability factor. After adjusting for confounding factors (e.g., parental and offspring non-BP psychopathology), BP offspring of BP parents showed the highest parental and child total and factor scores, followed by the non-BP offspring of BP parents, and then the offspring of the controls.

Conclusions

Mood lability overall and mania-like, anxious/depressed, and particularly irritability symptoms may be a prodromal phenotype of BP among offspring of parents with BP. Prospective studies are warranted to clarify whether these symptoms will predict the development of BP and/or other psychopathology. If confirmed, these symptoms may become a target of treatment and biological studies before BP develops.

Keywords: anxiety, bipolar disorder, bipolar offspring, Children’s Affective Lability Scale, depression, irritability, mania, mood lability

Bipolar disorder (BP) is a recurrent illness that usually has its onset during adolescence and is associated with substantial morbidity and impairment (1). Nonetheless, there is often a delay of up to a decade from the onset of the mood symptoms until proper diagnosis and treatment of BP (1, 2) increasing the risk of worse outcomes (2–4). Therefore, identification of early BP symptomatology could aid in earlier treatment and better psychosocial outcome.

Retrospective studies of youth and adults with BP consistently indicate increased irritability, mood lability, subclinical mood and anxiety symptomatology, and behavior and sleep problems may be potential prodromal symptoms of BP (5–12). Of these symptoms, mood lability, defined as sudden, exaggerated, unpredictable and developmentally inappropriate changes in mood, is one of the strongest potential prodromal symptoms for BP. However, it is important to note that as used in the literature, mood lability is an umbrella term that captures pathological changes across several mood states including irritability. Among the studies that reported mood lability (or irritability) as a prodromal for BP, Angst and colleagues (7) in a large prospective adult community study reported that, independent of family history, unstable mood regulation was the strongest risk factor for BP. Also, Egeland and colleagues (13) in a well-characterized sample of 58 Amish bipolar I disorder (BP-I) adults whose medical records from childhood were available, reported that the most frequently symptoms included episodic changes in depressed, irritable, anger, and increased energy. In this study, there was a 9–12-year time interval between appearance of the first symptoms and the onset of the BP-I. Finally, Correll and colleagues (14) also reported a long symptomatic prodromal phase prior to the first manic episode manifested by mood lability (including anger outbursts), subclinical manic and depressed symptoms, anxiety, and social isolation.

To obviate the biases encountered with retrospective investigations, and since the single most significant vulnerability factor for the development of BP is a family history of BP, studies have evaluated the prevalence of psychopathology in child and adolescent offspring of parents with BP. Using categorical as well as dimensional measurements, cross-sectional studies have reported higher levels of mood lability (including irritability and other rapid mood fluctuations), negative affect, depressed mood, anxiety, aggressive behaviors, and attention and sleep problems in offspring of parents with BP when compared with offspring of controls (8, 9, 12, 15–22). In the Pittsburgh Bipolar Offspring Study (BIOS) (18), from which the sample for the present study is derived, the offspring of parents with BP, particularly those offspring who already developed BP, had higher scores in the Total, Internalizing, Anxious/Depressed, Withdrawn/Depressed, and Aggressive Behavior scales of the Children Behavior Checklist (CBCL), the CBCL–Dysregulation Profile (CBCL-DP), and a sum of CBCL items associated with mood lability than the offspring of the control parents (17), independent of child and parental non-BP psychopathology. Using the Child Hostility Inventory, Farchione and colleagues (23) also reported high levels of irritability and hostility in the BIOS offspring of parents with BP when compared with offspring of the controls.

The above literature suggest that mood lability and its components (e.g., irritability) as well the presence of subclinical mood and anxiety symptoms are a potential prodromal phenotype for BP. However, these symptoms, and in particular mood lability, are ubiquitous among psychiatric disorders (24–28). In fact, whereas some have found mood lability to be associated with the development of BP (5, 11, 14, 29–32), others have reported that it increases the risk for anxiety and depressive disorders, antisocial behaviors, and suicidality, but not BP (33–38). Thus, further investigations with more clear definitions or instruments to ascertain mood lability and its components are warranted to clarify the association of these symptoms with pediatric BP in high-risk populations without full-blown BP.

Different methods have been used to ascertain mood lability such as single items and a composite of symptoms derived from instruments not specifically designed to ascertain mood lability, like the CBCL (e.g., 24, 26, 39–41). We therefore decided to use a parent-report (about their children) scale specifically developed to assess mood lability in youth, the Children’s Affective Lability Scale (CALS) (42). To compare and expand the original factor analysis of the CALS which was carried out with school children among whom there is less likelihood of mood symptomatology, and because the primary aim of our study was to identify prodromal symptoms of mania, a new factor analysis was performed.

In this study, we sought to investigate the prevalence of mood lability and its components in non-BP offspring of BP parents, BP offspring of BP parents, and offspring of community control parents. These comparisons will help to clarify whether excessive mood lability only exists in the BP offspring of BP parents or is also increased in the non-BP offspring of parents with BP. Moreover, since some control parents are healthy whereas others have non-BP psychopathology, we will be able to evaluate if excessive mood lability is associated with having a parent with BP or is non-specifically associated parental overall psychopathology. Based on the literature and prior BIOS results it was hypothesized that after adjusting for confounding factors (e.g., effect of parental and offspring non-BP psychopathology) non-BP offspring of BP parents will have significantly higher scores on the parent and child CALS and its subscales than the offspring of community control parents. In addition, after adjusting for confounding factors, BP offspring of BP parents will show higher CALS scores than the non-BP offspring of BP parents and the offspring of the control parents.

Methods

Sample

The methods for BIOS have been reported in detail elsewhere (18). In summary, parents with BP-I or bipolar II disorder (BP-II) were recruited through advertisement (53%), adult BP studies (31%), and outpatient clinics (16%). Exclusion criteria included current or lifetime diagnoses of schizophrenia, mental retardation, mood disorders secondary to substance abuse, medical conditions, or medications, and living more than 200 miles away from Pittsburgh. Control parents, with or without non-BP psychopathology, were recruited at random from the community matched by age, sex, and neighborhood with the BP parents. In addition to the exclusion criteria noted above, control parents were excluded if they had first-degree relatives with BP.

With the exception of children who were unable to participate (e.g., mental retardation) all offspring ages from each family were included in BIOS.

The CALS was completed in 298 offspring of 190 parents with BP and 192 offspring of 117 control parents. Of the offspring of BP parents, 257 offspring (of 174 parents) were either healthy or had non-BP psychopathology and 41 offspring (of 38 parents) met criteria for bipolar spectrum disorders. Of the offspring of controls parent, 38.5% had non-BP psychopathology and the rest were healthy. On average, two offspring per family were included in the study (18).

Instruments

DSM-IV psychiatric disorders for proband parents, and biological co-parents who participated in direct interviews (30%), were ascertained through the Structured Clinical Interview DSM-IV (SCID) (43), plus the attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), disruptive behavioral disorders (DBD), and separation anxiety disorder (SAD) sections from the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children, Present and Lifetime Version (KSADS-PL) (44). The Family History–Research Diagnostic Criteria method (FH-RDC) (45) plus ADHD and DBD items from the K-SADS were used to ascertain the psychiatric history of second-degree relatives, biological co-parents not seen for direct interview, and siblings of offspring who were too old (≥ 18 years) to be enrolled as participants in BIOS at intake.

Parents were interviewed about their children and children were directly interviewed for the presence of lifetime non-mood psychiatric disorders using the K-SADS-PL, the depression section of the K-SADS-P, and the K-SADS Mania Rating Scale (46).

Mood symptoms that were also in common with other psychiatric disorders (e.g., hyperactivity) were not rated as present in the mood sections unless they intensified with the onset of abnormal mood. Comorbid diagnoses were not assigned if they occurred exclusively during a mood episode. All diagnoses were made using the DSM-IV criteria. However, to avoid diagnosing youth with ‘soft’ BP symptoms, an operationalized criteria was used for bipolar disorder not otherwise specified (BP-NOS), as described in detail elsewhere (47).

Bachelor’s- or Master’s-level interviewers completed all assessments after intensive training for all instruments and after > 80% agreement with a certified rater. The overall SCID and K-SADS kappas for psychiatric disorders were ≥ 0.8. Approximately 90% of assessments were conducted in the subjects’ homes. To ensure blindness to parental diagnoses, the interviewers who met with the parent to assess parental psychopathology were different from the interviewers who assessed their children’s psychopathology. All data were presented to a child psychiatrist for diagnostic confirmation. The child psychiatrists were also blind to the psychiatric status of the parents.

Socioeconomic status (SES) was ascertained using the Hollingshead Scale (48).

Mood lability was ascertained using the CALS (42), which was derived from the Affective Lability Scale (ALS) (49), the latter of which was created to examine mood lability for adults with BP. The CALS has shown good psychometric properties in school age children and adolescents and inpatient and outpatient youth with diverse psychiatric disorders (42). It includes 20 items completed by parents about their children ≥ 6-years-old. Each item ascertains overall mood and behaviors scored on a scale of 1–5 (never/rarely, 1–3 times/month, 1–3 times/week, 4–6 times/week, and ≥ 1 times/day). The original factor analyses of the CALS data, which was obtained in a school sample using only parent reports, yielded two factors: (i) the Angry/Depressed factor (sudden and unpredictable mood, temper outbursts, crying, anger, irritability, sadness, anxiety, hyper-responsive reaction to simple requests, overly familiar with acquaintances, and sudden loss of interest in activity) and (ii) the Disinhibited/Impersistent factor (abrupt periods of silliness, talkativeness and laughing out of context, overly affectionate behaviors, and sudden loss of interest in activity).

Despite the fact that parental report of manic symptoms appears to be more reliable than information provided by children, (e.g., 50) offspring ≥ 8-years-old were also asked to complete the CALS since parents’ own mood state may bias their responses. Parents and their offspring were asked to complete the CALS to reflect the general mood and behaviors of the child.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Pittsburgh (Pittsburgh, PA, USA) and all participants provided written informed assent/consent as appropriate.

Statistical analysis

Differences in demographic and clinical characteristics among groups were analyzed using standard parametric statistical methods.

For ease of comparison with the original parent CALS factors, the current parent and offspring CALS data was analyzed using Factor Analysis with Oblique Rotation (51). Several factor solutions were analyzed using the ‘Scree Plot’ and only those solutions with factors with Eigenvalues > 1, with factor loadings of at least 0.40, and with adequate clinical face-validity were chosen. Internal consistency was measured using Cronbach’s alpha. With minimal differences, the new two-parental factor solution was similar to the original two-parental factors (42). However, as shown in detail below, a three-factor solution better separated the manic-like behaviors that were included in the original Disinhibited/Impersistent factor and teased apart the anxious/depressed and irritable symptomatology that were imbedded in the original Angry/Depressed factor. Because the comparison between the three groups of offspring using the two- and three-parental factor solutions yielded similar patterns, for simplicity, we only present the results of the new three-factor solution (the two-factor solution is available upon request).

Multivariate analysis of variance was used to compare the CALS total and each of the original and factors scores among BP offspring of BP parents, non-BP offspring of BP parents, and offspring of control parents. Backward stepwise models were used to select any parental (proband and co-parents) and offspring demographic and clinical characteristics that were significant in the univariate analyses. Only variables that survived the backward stepwise analyses were entered into the multivariate analyses. All comparisons were adjusted for within-family correlations and significant variables obtained through the stepwise models.

Since it is important to explore all potential phenotypes that may herald the onset of BP, all tests were two-sided with a significance level set at 0.05 without adjusting for multiple comparisons. However, results are presented with and without Bonferroni corrections.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics of proband parents (Table 1)

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics in BP parents with BP offspring, BP parents with non-BP offspring, and control parents

| BP parents with BP offspring (n = 38) | BP parents with non-BP offspring (n = 174) | Control parents (n = 117) | Statistics | Overall p-values | Pair-wise comparisons (p-values)a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 versus 2 | 1 versus 3 | 2 versus 3 | ||||||

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 37.6 (6.2) | 40.7 (7.2) | 42.2 (7.2) | χ2 = 6.3 | 0.002 | 0.01b | 0.0005b | 0.09 |

| Sex (% female) | 94.7 | 79.8 | 76.1 | χ2 = 6.3 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.01b | 0.40 |

| Race (% White) | 86.8 | 89.7 | 79.5 | χ2 = 6.0 | 0.05 | 0.60 | 0.30 | 0.01b |

| SES (SD) | 30.5 (12.2) | 34.2 (14.2) | 37.6 (13.3) | F = 4.5 | 0.01 | 0.13 | 0.006b | 0.04 |

| BP-I (%) | 60.5 | 69.5 | 0.0 | χ2 = 142.4 | < 0.0001 | – | – | – |

| BP-II (%) | 42.1 | 30.5 | 0.0 | χ2 = 50.7 | < 0.0001 | – | – | – |

| Depressive disorders (%) | N/A | N/A | 28.2 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Anxiety disorders (%) | 76.3 | 72.4 | 15.4 | χ2 = 100.9 | < 0.0001 | 0.60 | < 0.0001b | < 0.0001b |

| ADHD (%) | 28.9 | 32.3 | 0.8 | χ2 = 43.8 | < 0.0001 | 0.70 | < 0.0001b | < 0.0001b |

| DBD (%) | 50.0 | 35.3 | 7.7 | χ2 = 38.2 | < 0.0001 | 0.09 | < 0.0001b | < 0.0001b |

| SUD (%) | 65.8 | 64.4 | 27.3 | χ2 = 41.9 | < 0.0001 | 0.90 | < 0.0001b | < 0.0001b |

| Any Axis-I disorder (%) | 100.0 | 100.0 | 49.6 | χ2 = 130.3 | < 0.0001 | – | < 0.0001b | < 0.0001b |

BP = bipolar disorder; SD = standard deviation; SES = socioeconomic status; BP-I = bipolar I disorder; BP-II = bipolar II disorder; ADHD = attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; DBD = disruptive behavioral disorders; SUD = substance use disorders; N/A= non-applicable.

Group 1 = BP parents with BP offspring; Group 2 = BP parents with non-BP offspring; Group 3 = control parents.

Remained significant (p ≤ 0.05) after adjusting for multiple comparisons.

Average parental age was 40.9 ± 7.2 years, 80.2% were female, 85.7% Caucasian, and the average Hollingshead SES score was 35.0 (middle-class). BP parents with BP offspring were significantly younger and more likely to be female than the other two parental groups and had lower SES scores than the control parents. BP parents of non-BP offspring were more likely to be of African-American race than the BP parents of BP offspring.

There were no differences in comorbid psychiatric disorders between the BP parents with and without a BP offspring. However, both BP parent groups showed significantly higher rates of all disorders than the control parents.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of biological co-parents

There were no demographic differences between the three groups of biological co-parents and there were no clinical differences between the co-parents of the BP and non-BP offspring of parents with BP. Compared with the control co-parents, both groups of co-parents of the offspring of BP parents (those with and without offspring with BP) showed significantly more Axis-I disorders (52.9% versus 48.5% versus 31.2%, p = 0.004), bipolar spectrum disorders (9% versus 4% versus 0%), and substance use disorders (SUD) (38.2% versus 34.9% versus 22.4%, p = 0.04, respectively). There were no differences in the prevalence of major depression. The co-parents of the BP offspring of BP parents had more DBD than the control co-parents (6.1% versus 0%, p = 0.03).

All of the above differences were entered into the regression models.

Offspring demographic and clinical characteristics (Table 2)

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical characteristics in BP offspring of parents with BP, non-BP offspring of parents with BP, and offspring of control parents

| BP offspring of parents with BP (n = 41) | Non-BP offspring of parents with BP (n = 257) | Offspring of control parents (n = 192) | Statistics | Overall p- values | Pair-wise comparisons (p-values)a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 versus 2 | 1 versus 3 | 2 versus 3 | ||||||

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 13.8 (3.5) | 12.8 (3.4) | 12.8 (3.3) | χ2 = 1.8 | 0.16 | – | – | – |

| Sex (% female) | 58.5 | 47.9 | 56.8 | χ2 = 4.2 | 0.12 | – | – | – |

| Race (% White) | 85.4 | 81.3 | 79.7 | χ2 = 0.7 | 0.70 | – | – | – |

| BP-I (%) | 26.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | χ2 = 123.2 | < 0.0001 | – | – | – |

| BP-II (%) | 12.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | χ2 = 55.3 | < 0.0001 | – | – | – |

| BP-NOS (%) | 61.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | χ2 = 264.3 | < 0.0001 | – | – | – |

| Depressive disorders (%) | 0.0 | 13.2 | 5.7 | χ2 = 11.9 | 0.003 | 0.01 | 0.12 | 0.009b |

| Anxiety disorders (%) | 58.5 | 26.8 | 13.0 | χ2 = 40.6 | < 0.0001 | < 0.000b | < 0.0001b | 0.0004b |

| ADHD (%) | 39.0 | 24.9 | 14.6 | χ2 = 14.3 | 0.0008 | 0.06 | 0.0003b | 0.007b |

| DBD (%) | 56.1 | 16.3 | 9.4 | χ2 = 52.6 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001b | < 0.0001b | 0.03 |

| SUD (%) | 14.6 | 3.1 | 2.1 | χ2 = 15.5 | 0.0035 | 0.0012b | 0.0003b | 0.50 |

| Any Axis-I disorder (%) | 100.0 | 65.0 | 38.5 | χ2 = 63.8 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001b | < 0.0001b | < 0.0001b |

BP = bipolar disorder; SD = standard deviation; BP-I = bipolar I disorder; BP-II = bipolar II disorder; BP-NOS = bipolar disorder not otherwise specified; ADHD = attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; DBD = disruptive behavioral disorders; SUD = substance use disorders.

Group 1 = BP offspring of parents with BP; Group 2 = non-BP offspring of parents with BP; Group 3 = offspring of control parents.

Remained significant (p ≤ 0.05) after adjusting for multiple comparisons.

The average age of the offspring who completed the CALS was 12.9 ± 3.7 years, 52.2% were female, and 81.0% were Caucasian. There were no demographic differences among the three offspring groups. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders, other than depression, was significantly higher among BP offspring of BP parents than the offspring of controls. The non-BP offspring of BP parents also showed a significantly greater number of disorders than the offspring of the controls. Finally, the BP offspring of BP parents showed significantly more Axis-I disorders, anxiety, DBD, and SUD than the non-BP offspring of BP parents.

Parental CALS

As shown in Table 3, the most parsimonious and clinically relevant solution included the Irritability, Mania, and Anxiety/Depression factors. All factors showed good internal consistency coefficient (Cronbach’s α: 0.82–0.93), and high commonalities (0.42–0.81). Most of the variance was accounted for by the Irritability factor (49%) followed by the Mania (9.2%) and Anxiety/Depression (5.7%) factors. For the items included in each of these factors, refer to Table 3. One of the items that factored in the Mania factor, ‘does an activity and suddenly stops’, may represent the pronounced swings of energy/activity observed in mania, but this symptom may be present in many psychiatric disorders. Analyses with and without this item yielded the same results. Interestingly a factor analysis including the parental and offspring data together, with exception of one item, yielded identical results.

Table 3.

Parent–Children Affective Lability Scale: Factor Analyses

| Items/Factorsa | Irritability | Mania | Anxiety/Depression |

|---|---|---|---|

| It is hard to tell what will set him/her off into a blow-up of temper | 0.95 | ||

| You never know when he/she is going to blow up | 0.90 | ||

| Suddenly loses his/her temper (may yell, cuss, or throw something) when you would not expect | 0.89 | ||

| Appears very angry (yells, uses abusive language) in response to a simple request | 0.84 | ||

| It is hard to tell what mood he/she will be in | 0.82 | ||

| Has bursts of crabbiness or irritability | 0.73 | ||

| Suddenly starts to cry for little or no apparent reason, more so than other children his/her age | 0.41 | ||

| Suddenly starts to laugh about something that most people do not think is very funny | 0.81 | ||

| Suddenly is overly familiar with people he/she barely knows | 0.72 | ||

| Has bursts of increased talking | 0.68 | ||

| Has periods of time when he/she talks about the same thing over and over | 0.65 | ||

| Have bursts of being overly affectionate for little reason, hugging or kissing more than you would expect. | 0.63 | ||

| Has bursts of silliness for little or no apparent reason | 0.62 | ||

| Does an activity and then suddenly stops and says he/she is tired | 0.47 | ||

| Complains of short periods when he/she feels shaky, or his/her heart is pounding, or he/she has difficulty breathing (not due to asthma or another medical problem) | 0.95 | ||

| Has bursts of being nervous or fidgety | 0.55 | ||

| Suddenly becomes tense or anxious | 0.49 | ||

| Suddenly appears sad, depressed, and down in the dumps for no apparent reason | 0.49 |

Items with factor loadings < 0.40 were not included.

To evaluate the external validity of the CALS comparing the parental CALS total scores with the scores of the Total, Internalizing, and Externalizing scores of the CBLC and the CBCL-DP. The Pearson correlations ranged from 0.63 for the CBCL internalizing score to 0.74 for the CBCL-DP (all p-values < 0.001). There were no differences between the offspring of BP parents and the offspring of controls.

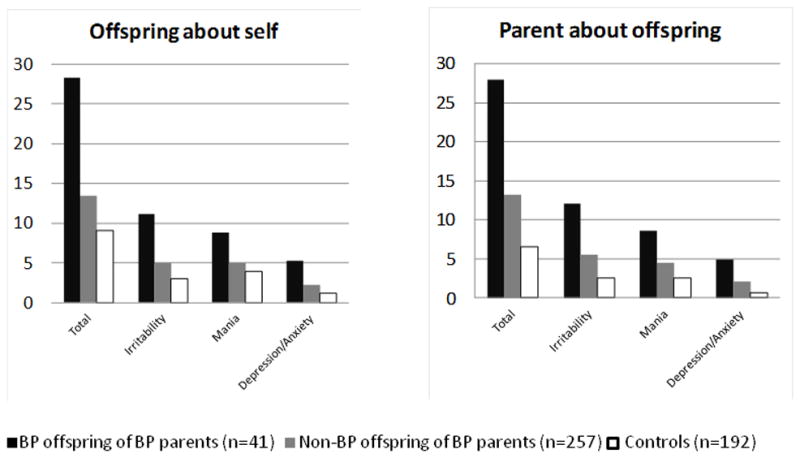

The BP offspring of BP parents showed significantly higher Total, Irritability, Mania, and Anxiety/Depression scores than the non-BP offspring of BP parents and the offspring of control parents. The non-BP offspring of BP parents also showed significantly higher scores in the Total and each of the factors than the offspring of control parents (all p-values < 0.0001 after adjusting for within-family correlations). As shown in Table 4 and Figure 1, after adjusting for within-family correlations and offspring’s (i) anxiety, ADHD, and DBD; (ii) parental age, sex, and anxiety; and (iii) co-parents’ BP, all of the above comparisons remained significant with p-values ≤ 0.01.

Table 4.

Parent-completed and offspring-completed Children’s Affective Lability Scale (CALS) comparison between BP offspring of parents with BP, Non-BP offspring of parents with BP, and offspring of control parents

| BP offspring of parents with BP (n = 41) | Non-BP offspring of parents with BP (n = 257) | Offspring of control parents (n = 192) | Statistics (F) | Overall adjusted p-valuesa | Adjusted pair-wise comparisons (p-values)a,b | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 versus 2 | 1 versus 3 | 2 versus 3 | ||||||

| CALS-parent | ||||||||

| Total | 27.98 (17.66) | 13.28 (12.98) | 6.51 (8.11) | 23.95 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001c | < 0.0001c | 0.0003c |

| Irritability | 12.12 (8.15) | 5.53 (6.13) | 2.58 (3.97) | 19.53 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001c | < 0.0001c | 0.005c |

| Mania | 8.63 (6.04) | 4.46 (4.62) | 2.61 (3.40) | 19.02 | 0.0001 | < 0.0001c | < 0.0001c | 0.01c |

| Anxiety/Depression | 4.93 (4.23) | 2.08 (2.59) | 0.72 (1.38) | 22.28 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001c | < 0.0001c | 0.0002c |

| CALS-offspring | ||||||||

| Total | 28.33 (16.54) | 13.48 (12.55) | 9.02 (10.78) | 12.60 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001c | < 0.0001c | 0.10 |

| Irritability | 11.15 (7.13) | 4.96 (5.35) | 3.03 (4.44) | 10.58 | < 0.0001 | 0.0001c | < 0.0001c | 0.05 |

| Mania | 8.79 (5.26) | 4.95 (4.73) | 3.86 (4.27) | 6.41 | 0.0021 | 0.0006c | 0.001c | 0.77 |

| Anxiety/Depression | 5.31 (3.98) | 2.21 (2.91) | 1.21 (2.15) | 21.24 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001c | < 0.0001c | 0.03 |

Values listed as mean (standard deviation). BP = bipolar disorder.

CALS parents: adjusting for within family correlations and offspring’s anxiety, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and disruptive behavioral disorders (DBD); and parental age, sex, and anxiety. CALS offspring: adjusting within family correlations and offspring’s anxiety, ADHD, and DBD; parental anxiety and DBD; and co-parents’ any Axis-I disorders.

Group 1 = BP offspring of parents with BP; Group 2 = non-BP offspring of parents with BP; Group 3 = offspring of control parents.

Remained significant (p ≤ 0.05) after adjusting for multiple comparisons.

Fig. 1.

Offspring and parental Children’s Affective Lability Scale (CALS) scores. Samples represent the number of CALS completed. Except for the Child CALS Mania and Total scores between the non-BP offspring of parents with BP and the offspring of the control parents, all other between group comparisons were significant with p-values of 0.05. BP = bipolar disorder.

There were no differences in the BP parents’ CALS scores between BP offspring with BP-I/BP-II and BP-NOS. Also, BP offspring with any current mood episodes (e.g., depression, mania, mixed) showed significantly higher CALS total and in each of the factors scores when compared with BP offspring with past mood episodes. Comparisons between the BP offspring with only past mood episodes with the non-BP offspring of BP parents and offspring of controls yielded the same pattern of results as noted above (all p-values < 0.02).

CALS totals and each factor score were significantly higher for the offspring of BP parents who were in a current mood episode compared to offspring of BP parents not in a current mood episode (all p-values < 0.02). After adjusting for the BP and control parents’ current mood state the magnitude of the statistical differences in CALS scores among the three groups of offspring showed in Table 4 diminished, but remained significant (all p-values ≤ 0.02). Except for the mania factor between the non-BP offspring of parents with BP and the offspring of the control parents, all results remained significant after adjusting for Bonferroni.

Offspring CALS

A two-factor solution was obtained. The first factor included identical items to those included in the Irritability and Anxiety/Depression parental factors and the second factor included the same manic-like items in the parental Mania factor. The two factors showed good internal consistency coefficient with Cronbach’s α = 0.91 and 0.79 and accounted for 44% and 7% of the variance, respectively.

To compare these results with those of the parents, in addition to the two-factors, between-group comparisons were also done using the three parental factors noted above. Both approaches yielded similar results. Thus, only the results with three factors are presented. The Pearson correlation coefficient between the total parent and child CALS scores was 0.51 (p < 0.0001).

Similar to the Parent CALS, before any demographic and clinical covariate adjustments, all between-group comparisons were significant with p-values < 0.0001. As depicted in Table 4 and Figure 1, after adjusting for within-family correlations and offspring’s (i) anxiety, ADHD, and DBD, (ii) parental anxiety and DBD, and (iii) co-parents’ any Axis-I disorders, the BP offspring of BP parents showed significantly higher Total, Irritability, Mania, and Anxiety/Depression scores than the non-BP offspring of BP parents and the offspring of control parents. The non-BP offspring of BP parents showed significantly higher Irritability and Anxiety/Depression scores than the offspring of control parents (all p-values < 0.05). Most of the effects of the covariates were due to the parental covariates. In fact, after entering into the stepwise regression only the offspring covariates, with the exception of a trend (p = 0.06) between the non-BP offspring and healthy controls in the ‘manic’ factor, all between-group comparisons were significant (all p-values ≤ 0.03).

Within the offspring with BP, there were no differences in the CALS scores between offspring with BP-I/BP-II and BP-NOS. BP offspring with any current mood episodes showed significantly higher CALS total in each factors scores, than BP offspring with past mood episodes.

Comparisons between the BP offspring with only past mood episodes with non-BP offspring of BP parents and the offspring of the control parents, yielded the same pattern of results as noted above (all p-values < 0.004). About 14% of the offspring, especially those diagnosed with BP, were on pharmacological treatment for psychiatric disorders. Analyses excluding offspring on pharmacological treatments yielded similar results.

Discussion

The parental and offspring CALS in this sample showed that the mood lability construct of this scale includes irritability, mania-like, anxiety and depression symptomatology. Parent and offspring CALS scores were moderately correlated and parental CALS strongly correlated with the CBCL, especially the CBCL-DP, a phenotype that also measures mood lability. In this study, mood lability, particularly irritability, appears to be a potential candidate as prodromal phenotype for BP in offspring of parents with BP. In fact, the non-BP offspring of BP parents had higher irritability and anxiety/depression scores even after adjusting for the presence of parental and offspring non-BP psychopathology (Fig. 1). All CALS scores were significantly higher in BP offspring with any subtype of BP and this was not explained by comorbid disorders like ADHD and oppositional defiant disorder (ODD). There were no effects of current pharmacological treatment. As expected, offspring with current mood symptomatology showed higher CALS scores than those with past episodes. However, BP offspring with past mood episodes continued to show higher CALS scores than offspring with non-BP disorders and offspring of control parents. As others have reported (52, 53), parents who experienced a mood episode while completing the CALS, scored their offspring higher than parents with past mood episodes. Nevertheless, results remained significant after adjusting for current parental mood episodes.

Before discussing the above results, the following limitations need to be considered. First, the cross-sectional design precludes causal interpretations. Since BIOS is a prospective study, future studies will evaluate the trajectory of mood lability to evaluate whether this phenotype is indeed a prodrome for BP and/or other psychopathology. Second, for all analyses, we adjusted for between-group differences in offspring non-BP symptomatology (e.g., ADHD and ODD). However, the symptoms of some of these disorders may themselves be prodromal for BP. Finally, the parents with BP who agreed to participate in BIOS could have had more psychopathology than those who did not participate. Nevertheless, the rates of psychiatric disorders in parents with BP in our study were similar to those reported in the adult BP literature (54).

Total CALS scores and scores on each of the factors were significantly higher in youth who already developed BP. These results are not surprising because in addition to irritability, which is high in BP, the CALS includes mania and depression symptomatology. Nevertheless, similar results have been consistently found in youth with BP using other instruments (e.g., the CBCL), even if these instruments do not include classic BP symptomatology (22, 40, 55, 56).

The increased CALS total and factor scores in youth with BP may be a non-specific state marker that reflects BP severity (17, 27, 37, 55, 56). However, consistent with our prior findings and other studies utilizing the CBCL (17, 22) and the Children Hostility Inventory (23), we found that offspring of BP who have not yet developed BP also had high overall mood lability, irritability and depression/anxiety symptomatology when compared with the offspring of controls. Similar findings have been reported in other high-risk studies by different investigators using different methodologies (5, 8–11, 14–17, 19, 20, 57). However, since the non-BP offspring of BP parents had significantly more other Axis-I disorders than the offspring of controls, these disorders could have accounted for the higher CALS scores. Nevertheless, after adjusting for the presence of existing offspring non-BP Axis-I disorders, the non-BP offspring of BP parents still showed significant differences in the CALS scores when compared with the offspring of control parents. These results converge with the existing literature to suggest that increased scores in mood lability and irritability and subclinical mania and anxiety/depression symptomatology may indeed be good candidates as a prodromal phenotype for BP among offspring of parents with BP (8–12, 14, 57).

If future studies, particularly those with longitudinal methodology, demonstrate that excessive mood lability and its components (particularly irritability) are prodromal symptoms for BP, these phenotypes may become a target of treatment and biological studies before syndromal BP develops (12, 58). Nevertheless, irritability, as well as mania-like and subclinical depression and anxiety symptoms, are common in community samples of children (24, 26, 28, 39), and frequently found in many psychiatric disorders (1, 24–28, 37, 55). Moreover, these symptoms have not always been associated with increased risk for BP, but rather depression or anxiety (5, 14, 29–39). As a consequence, just because a child has increased irritability, mania-like, and anxiety/depression symptomatology does not mean that this child has or will develop BP (28, 59, 60). On the other hand, perhaps the presence of mood and anxiety symptoms that are above and beyond the child’s emotional and cognitive developmental stage and that are episodic, not accounted for by other non-mood disorders, and appear in the context of family history of BP are risk markers for BP. Continuous follow-up of the offspring recruited into BIOS into adulthood will help clarify whether the above symptoms will specifically predict the development of BP or other psychopathology, and whether this association is moderated by parental BP. In the interim, increased vigilance and caution is warranted when interpreting and treating mood lability and related symptoms among high-risk offspring of parents with BP.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Mental Health R01 MH060952 (BB). The authors express thanks to the families for their participation; to Melissa Cade, Nicholas Curcio, Ronna Currie, Lindsay Virgin, and other staff; and to Shelli Avenevoli Ph.D. from the National Institutes of Mental Health for their support.

Footnotes

Disclosures

BB has received research support from the National Institutes of Mental Health; and receives royalties from Random House, Inc., and Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. BIG has received research support from Pfizer; is a consultant for Bristol-Myers Squibb; and has received speakers honoraria from Purdue Pharma. DAA, KM, MBH, JF, SI, WH, RSD, TG, DB, CDL, DS, and DJK have no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Birmaher B, Axelson D, Pavaluri M. Bipolar disorder. In: Martin A, Volkmar FR, Lewis M, editors. Lewis’ Child and Adolescent Psychiatry: A Comprehensive Textbook. 4. London: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chengappa KN, Kupfer DJ, Frank E, et al. Relationship of birth cohort and early age at onset of illness in a bipolar disorder case registry. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1636–1642. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.9.1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perlis RH, Miyahara S, Marangell LB, et al. Long-term implications of early onset in bipolar disorder: data from the first 1000 participants in the systematic treatment enhancement program for bipolar disorder (STEP-BD) Biol Psychiatry. 2004;55:875–881. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leverich GS, Post RM, Keck PE, Jr, et al. The poor prognosis of childhood-onset bipolar disorder. J Pediatr. 2007;150:485–490. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.10.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fergus EL, Miller RB, Luckenbaugh DA, et al. Is there progression from irritability/dyscontrol to major depressive and manic symptoms? A retrospective community survey of parents of bipolar children. J Affect Disord. 2003;77:71–78. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00176-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yung AR, McGorry PD. The prodromal phase of first-episode psychosis: past and current conceptualizations. Schizophr Bull. 1996;22:353–370. doi: 10.1093/schbul/22.2.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Angst J, Gamma A, Endrass J. Risk factors for the bipolar and depression spectra. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 2003;(418):15–19. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.108.s418.4.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leopold K, Ritter P, Correll CU, et al. Risk constellations prior to the development of bipolar disorders: rationale of a new risk assessment tool. J Affect Disord. 2012;136:1000–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duffy A. The early course of bipolar disorder in youth at familial risk. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;18:200–205. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Correll CU, Penzner JB, Lencz T, et al. Early identification and high-risk strategies for bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9:324–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Howes OD, Lim S, Theologos G, Yung AR, Goodwin GM, McGuire P. A comprehensive review and model of putative prodromal features of bipolar affective disorder. Psychol Med. 2011;41:1567–1577. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710001790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luby JL, Navsaria N. Pediatric bipolar disorder: evidence for prodromal states and early markers. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2010;51:459–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02210.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Egeland JA, Hostetter AM, Pauls DL, Sussex JN. Prodromal symptoms before onset of manic-depressive disorder suggested by first hospital admission histories. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:1245–1252. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200010000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Correll CU, Penzner JB, Frederickson AM, et al. Differentiation in the preonset phases of schizophrenia and mood disorders: evidence in support of a bipolar mania prodrome. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33:703–714. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang KD, Steiner H, Ketter TA. Psychiatric phenomenology of child and adolescent bipolar offspring. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:453–460. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200004000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wals M, Hillegers MH, Reichart CG, Ormel J, Nolen WA, Verhulst FC. Prevalence of psychopathology in children of a bipolar parent. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:1094–1102. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200109000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diler RS, Birmaher B, Axelson D, et al. Dimensional psychopathology in offspring of parents with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2011;13:670–678. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2011.00966.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Birmaher B, Axelson D, Monk K, et al. Lifetime psychiatric disorders in school-aged offspring of parents with bipolar disorder: the Pittsburgh Bipolar Offspring study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:287–296. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dienes KA, Chang KD, Blasey CM, Adleman NE, Steiner H. Characterization of children of bipolar parents by parent report CBCL. J Psychiatr Res. 2002;36:337–345. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(02)00019-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones SH, Tai S, Evershed K, et al. Early detection of bipolar disorder: a pilot familial high-risk study of parents with bipolar disorder and their adolescent children. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8:362–372. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2006.00329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singh MK, DelBello MP, Stanford KE, et al. Psychopathology in children of bipolar parents. J Affect Disord. 2007;102:131–136. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giles LL, DelBello MP, Stanford KE, Strakowski SM. Child behavior checklist profiles of children and adolescents with and at high risk for developing bipolar disorder. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2007;38:47–55. doi: 10.1007/s10578-006-0041-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Farchione TR, Birmaher B, Axelson D, et al. Aggression, hostility, and irritability in children at risk for bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9:496–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00390.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stringaris A, Goodman R. Mood lability and psychopathology in youth. Psychol Med. 2009;39:1237–1245. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708004662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sobanski E, Banaschewski T, Asherson P, et al. Emotional lability in children and adolescents with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): clinical correlates and familial prevalence. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2010;51:915–923. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barkley RA, Fischer M. The unique contribution of emotional impulsiveness to impairment in major life activities in hyperactive children as adults. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49:503–513. doi: 10.1097/00004583-201005000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carlson GA, Glovinsky I. The concept of bipolar disorder in children: a history of the bipolar controversy. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2009;18:257–271. vii. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stringaris A, Santosh P, Leibenluft E, Goodman R. Youth meeting symptom and impairment criteria for mania-like episodes lasting less than four days: an epidemiological enquiry. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2010;51:31–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02129.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson JG, Cohen P, Brook JS. Associations between bipolar disorder and other psychiatric disorders during adolescence and early adulthood: a community-based longitudinal investigation. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1679–1681. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.10.1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim-Cohen J, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Harrington H, Milne BJ, Poulton R. Prior juvenile diagnoses in adults with mental disorder: developmental follow-back of a prospective-longitudinal cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:709–717. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.7.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nock MK, Kazdin AE, Hiripi E, Kessler RC. Lifetime prevalence, correlates, and persistence of oppositional defiant disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2007;48:703–713. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01733.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Biederman J, Petty CR, Monuteaux MC, et al. The Child Behavior Checklist-Pediatric Bipolar Disorder profile predicts a subsequent diagnosis of bipolar disorder and associated impairments in ADHD youth growing up: a longitudinal analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70:732–740. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Halperin JM, Rucklidge JJ, Powers RL, Miller CJ, Newcorn JH. Childhood CBCL bipolar profile and adolescent/young adult personality disorders: a 9-year follow-up. J Affect Disord. 2011;130:155–161. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stringaris A, Cohen P, Pine DS, Leibenluft E. Adult outcomes of youth irritability: a 20-year prospective community-based study. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:1048–1054. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08121849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stringaris A, Baroni A, Haimm C, et al. Pediatric bipolar disorder versus severe mood dysregulation: risk for manic episodes on follow-up. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49:397–405. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Althoff RR, Verhulst FC, Rettew DC, Hudziak JJ, van der Ende J. Adult outcomes of childhood dysregulation: a 14-year follow-up study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49:1105–1116. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leibenluft E. Severe mood dysregulation, irritability, and the diagnostic boundaries of bipolar disorder in youths. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:129–142. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10050766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meyer SE, Carlson GA, Youngstrom E, et al. Long-term outcomes of youth who manifested the CBCL-Pediatric Bipolar Disorder phenotype during childhood and/or adolescence. J Affect Disord. 2009;113:227–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carlson GA, Kashani JH. Manic symptoms in a non-referred adolescent population. J Affect Disord. 1988;15:219–226. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(88)90019-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Diler RS, Birmaher B, Axelson D, et al. The Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) and the CBCL-bipolar phenotype are not useful in diagnosing pediatric bipolar disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2009;19:23–30. doi: 10.1089/cap.2008.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Caspi A, Henry B, McGee RO, Moffitt TE, Silva PA. Temperamental origins of child and adolescent behavior problems: from age three to age fifteen. Child Dev. 1995;66:55–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gerson AC, Gerring JP, Freund L, et al. The Children’s Affective Lability Scale: a psychometric evaluation of reliability. Psychiatry Res. 1996;65:189–198. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(96)02851-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I disorders (SCID I) New York: Biometric Research Department; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent DA, Ryan ND, Rao U. K-SADS-PL. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:1208. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200010000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Endicott J, Andreasen N, Spitzer RL. Family History Research Diagnostic Criteria. New York: New York Psychiatric Institute Ciometric Research; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Axelson D, Birmaher BJ, Brent D, et al. A preliminary study of the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children mania rating scale for children and adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2003;13:463–470. doi: 10.1089/104454603322724850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Axelson DA, Birmaher B, Strober MA, et al. Course of subthreshold bipolar disorder in youth: diagnostic progression from bipolar disorder not otherwise specified. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50:1001–1016.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hollingshead AB. Four Factor Index of Social Status. New Haven: Yale University Department of Sociology; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Harvey PD, Greenberg BR, Serper MR. The affective lability scales: development, reliability, and validity. J Clin Psychol. 1989;45:786–793. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198909)45:5<786::aid-jclp2270450515>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Youngstrom EA, Findling RL, Calabrese JR, et al. Comparing the diagnostic accuracy of six potential screening instruments for bipolar disorder in youths aged 5 to 17 years. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43:847–858. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000125091.35109.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Johnson RA, Wichern DW. Applied Multivariate Statistical Analysis. 6. Prentice Hall; 2007. Factor Analysis and Inference for Structured Covariance Matrices. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chilcoat HD, Breslau N. Does psychiatric history bias mothers’ reports? An application of a new analytic approach. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:971–979. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gartstein MA, Bridgett DJ, Dishion TJ, Kaufman NK. Depressed mood and maternal report of child behavior problems: another look at the Depression-Distortion Hypothesis. J Appl Dev Psychol. 2009;30:149–160. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Merikangas KR, Akiskal HS, Angst J, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Archiv Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:543–552. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Axelson D, Birmaher B, Strober M, et al. Phenomenology of children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders. Archiv Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:1139–1148. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.10.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Geller B, Zimerman B, Williams M, et al. DSM-IV mania symptoms in a prepubertal and early adolescent bipolar disorder phenotype compared to attention-deficit hyperactive and normal controls. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2002;12:11–25. doi: 10.1089/10445460252943533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shaw JA, Egeland JA, Endicott J, Allen CR, Hostetter AM. A 10-year prospective study of prodromal patterns for bipolar disorder among Amish youth. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44:1104–1111. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000177052.26476.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Miklowitz DJ, Chang KD. Prevention of bipolar disorder in at-risk children: theoretical assumptions and empirical foundations. Dev Psychopathol. 2008;20:881–897. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Merikangas KR, Cui L, Kattan G, Carlson GA, Youngstrom EA, Angst J. Mania with and without depression in a community sample of US adolescents. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69:943–951. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Findling RL, Youngstrom EA, Fristad MA, et al. Characteristics of children with elevated symptoms of mania: the Longitudinal Assessment of Manic Symptoms (LAMS) study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:1664–1672. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05859yel. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]