Abstract

Thyroid hormones T3/T4 participate in the fine tuning of development and performance. The formation of thyroid hormones requires the accumulation of I− by the electrogenic Na+/I− symporter, which depends on the electrochemical gradient across the cell membrane and thus on K+ channel activity. The present paper explored whether Kcnq1, a widely expressed voltage-gated K+ channel, participates in the regulation of thyroid function. To this end, Kcnq1 expression was determined by RT-PCR, confocal microscopy, and thyroid function analyzed in Kcnq1 deficient mice (Kcnq1−/−) and their wild-type littermates (Kcnq1+/+). Moreover, Kcnq1 abundance and current were determined in the thyroid FRTL-5 cell line. Furthermore, mRNA encoding KCNQ1 and the subunits KCNE1-5 were discovered in human thyroid tissue. According to patch-clamp TSH (10 mUnits/ml) induced a voltage-gated K+ current in FRTL-5 cells, which was inhibited by the Kcnq inhibitor chromanol (10 μM). Despite a tendency of TSH plasma concentrations to be higher in Kcnq1−/− than in Kcnq1+/+ mice, the T3 and T4 plasma concentrations were significantly smaller in Kcnq1−/− than in Kcnq1+/+ mice. Moreover, body temperature was significantly lower in Kcnq1−/− than in Kcnq1+/+ mice. In conclusion, Kcnq1 is required for proper function of thyroid glands.

Keywords: K+ channels, Body temperature, Thyroid hormones, T3/T4, TSH, KCNE, Chromanol

Introduction

The pore-forming K+ channel α-subunit KCNQ1 (KvLQT1) is expressed in a wide variety of tissues including the heart [2, 30], skeletal muscle [10], stria vascularis [42], the renal proximal tubule [39], gastric parietal cells [7, 11, 14], intestine [7, 14, 26, 33, 35, 39], and liver [8, 20, 21].

KCNQ1 is important for a variety of crucial functions including cardiac rhythm [2, 25, 30], hearing [4, 23], gastric acid secretion [23, 32], as well as intestinal and renal transport [40]. Lack of KCNQ1 has been shown to enhance insulin sensitivity [3] and KCNQ1 polymorphisms were associated with diabetes [38, 43].

In epithelia, KCNQ1 contributes to the maintenance of cell membrane potential, which is an important driving force for electrogenic transport [39]. In thyroid glands, an electrical driving force is required for proper function of the Na+-coupled iodide transporter NIS [5]. KCNQ1 further participates in the regulation of cell volume [1, 12, 20, 21, 41] and cell proliferation [16, 18, 24, 29, 31, 36, 37]. Cell proliferation plays a critical role in the regulation of thyroid follicular mass [9]. The thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) stimulates cell proliferation and thus increases the thyroid mass [9]. The increased number of T3/T4-secreting cells thus augments the release of the hormones.

The present study was performed to elucidate whether Kcnq1 is expressed in thyroid glands and whether the channel participates in the regulation of thyroid function. During the course of this study, Kcnq1 has indeed been indirectly implicated in thyroid function [28]. In that study, evidence was presented that lack of Kcne2 leads to hypothyroidism and it was suggested that this phenotype was likely due to loss of potassium channels formed by Kcne2/Kcnq1 heterodimers. Our results indeed demonstrate that Kcnq1 is expressed in the thyroid and that Kcnq1-deficient mice suffer from mild hypothyroidism.

Methods

The mice were bred in the animal facilities of the University of Tübingen and Hannover Medical School. All animal experiments were conducted according to the German law for the welfare of animals and were approved by local authorities.

Experiments were performed in mice deficient in Kcnq1 (Kcnq1−/−) and their wild-type littermates (Kcnq1+/+) generated as previously described [4]. For the study, 4–10-month-old Kcnq1 knockout (Kcnq1−/−; 2–8 males, 2–7 females) and their wild-type littermates (Kcnq1+/+; 3–8 males, 3–9 females) were selected (TSH levels were in addition measured in 3-week-old mice). Prior to the experiment, the age- and sex-matched mice were fed with control diet (1310/1314, Altromin, Lage, Germany) and were allowed free access to tap water.

To obtain blood specimens, animals were lightly anesthetized with diethylether (Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany) and about 200 μl of blood were withdrawn into heparinized capillaries by puncturing the retro-orbital plexus. Plasma concentrations of free triiodothyronine (fT3), free thyroxine (fT4), and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) were measured using ELISA-kits (Alpha Diagnostics Intl. Inc, San Antonio, Texas, USA, Shibayagi Co., Ltd., Ishihara, Shibukawa, Gunma Pref., Japan). Body temperature was determined utilizing a thermosensor inserted through the anus into sigmoidal colon.

The Kcnq1 transcript levels in mouse thyroid gland and in FRTL-5 cells as well as the KCNQ1 and KCNE1-5 transcript levels in human thyroid gland, colon, stomach, and heart (Stratagene—Agilent Technology, Waldbronn, Germany) were measured by Real-Time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). To this end total RNA was extracted from FRTL-5 cells and mouse thyroid tissue in TriFast (Peqlab, Erlangen, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Reverse transcription of total RNA (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA) was performed using random hexamers (Roche Diagnostics, Penzberg, Germany) and SuperScriptII reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). PCR amplification of the respective genes were set up in a total volume of 20 μl using 40 ng of cDNA, 500 nM forward and reverse primer and 2× iTaq Fast SYBR Green (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Cycling conditions were performed as follows: initial denaturation at 95 C for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s, 55°C for 15 s and 68°C for 20 s. The primers used for amplification are listed in Table 1. Specificity of PCR products was confirmed by analysis of a melting curve. Real-time PCR amplifications were performed on a CFX96 cycler (Bio-Rad, München, Germany) and all experiments were done in doublets. Amplification of the housekeeping gene Tbp was performed to standardize the amount of sample RNA. Relative quantification of gene expression was performed using the ΔΔct method as described earlier [27].

Table 1.

Primers used for the amplification (5′–>3′ orientation)

| Mouse Kcnq1 | fw: ACACTGCTGGAAGTAAGCAC | rev: TGCGCACCATAAGGTTCAGG |

|---|---|---|

| Mouse Tbp | fw: CACTCCTGCCACACCAGCTT | rev: TGGTCTTTAGGTCAAGTTTACAGCC |

| KCNQ1 | fw: AGATCCTGAGGATGCTACACGTCGA | rev: ATAGCCGATGGTGGTGACTGTGACC |

| KCNE1 | fw: ATGATCCTGTCTAACACCACAGCGG | rev: CTTCTTGGAGCGGATGTAGCTCAGC |

| KCNE2 | fw: CAAGCCAAAGTTGATGCTGAGAACT | rev: CCGCACCAATGTTCTCATGGATGGT |

| KCNE3 | fw: ATGGAGACTACCAATGGAACGGAGA | rev: TACAGCAAATAGAAACATGACAAAG |

| KCNE4 | fw: ATGCTGAAAATGGAGCCTCTGAACA | rev: TCTTCTCCCGCCTCTTGGATTTCAT |

| KCNE5 | fw: AACCCTTCTGAGCCGCCTGTTGCTC | rev: CGGCCAAGCAGGCGTAGAAGATCAT |

| TBP | fw: GCCCGAAACGCCGAATAT | rev: CCGTGGTTCGTGGCTCTCT |

| Rat Kcnq1 | fw: TCTTGAGAACAAACAGCTTTGCAGA | rev: AACAAAGATGGCTTCCCAATGGACT |

| Rat Tbp | fw: ATGGACCAGAACAACAGCCTTCCAC | rev: CTGCTGAGATGTTGATTGCTGTACT |

For immunohistochemistry, thyroid glands were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, thereafter incubated in 30% sucrose overnight and frozen in Tissue Tek (Polyscience). Then, 12-μm cryosections were prepared. For immunhistochemistry cryosections were air-dried, treated with a fixation solution (4% PFA/PBS, 0.2% Igepal, 0.1% Na-deoxycholate) for 5 min and then washed with PBS. Thereafter, the slides were incubated for 30 min at room temperature in blocking solution (3% NGS, 2% BSA, 0.5% Igepal) and then incubated overnight at 4°C with the primary antibodies diluted in carrier solution (2% BSA, 0.5% Igepal). On the next day, the slides were washed with PBS followed by another incubation step with blocking solution for 15 min at room temperature. Then, the second antibody diluted in carrier solution was added and the slides were incubated for 1 h at room temperature followed by washing with PBS. Finally, the sections were covered with mounting medium (ProLong® Gold Antifade Reagent, Invitrogen) and stored at 4°C in the dark until analysis. A primary antibody directed against Kcnq1 from Abcam (1:1000) was used. Secondary antibodies were Alexa Fluor 488 goat α-rabbit (1:2,000), Draq 5 (1:1,000; Biostatus limited) for nuclear staining, and rhodamine phalloidin (1:1,000; Invitrogen) for actin labeling.

For cell surface biotinylation of FRTL-5 cells, the cells were rinsed twice with ice-cold PBS buffer. Cells were then incubated for 30 min at 4°C in 0.5 mg/ml Sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotin (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) diluted in ice-cold PBS buffer. After washing twice with ice-cold PBS supplemented with 0.1% BSA (w/v), the cells were dissolved in lysis buffer containing 20 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM Na2HPO4, 1 mM EDTA (pH 8.0), 80 mM sucrose, 1 mM PMSF. Then the cells were rotated for 1 h at 4°C. Thereafter 600 μg of extracted protein was incubated overnight at 4°C with 50 μl neutravidin beads (Pierce). The next day the proteins with the beads were centrifugated at 13,000 rpm at 4°C for 2 min and the supernatant was removed. Then, to wash the beads 500 μl of buffer (1% Triton X100, 0.1 M NaCl, 0,02 M Tris pH 7,4) supplemented with complete protease inhibitor (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) was added and thereafter another centrifugation step at 13,000 rpm at 4°C for 2 min was accomplished. This washing step was recapitulated for four times. Thereafter protein was eluted from the beads by incubation with 20 μl dH2O and 5 μl 4× protein loading buffer (Carl Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany). The biotinylated membrane protein was separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred electrophoretically to a nitrocellulose membrane. After blocking with 5% nonfat dry milk in TBS (pH 7.4)/0.15% Tween 20 for 1 h at room temperature, the blots were incubated with the primary antibody (Abcam, rabbit polyclonal to Kcnq1) at 4°C overnight (1:1,000 in TBS/0.15% Tween 20/5% non-fat dry milk). After washing, the first antibody was detected by secondary goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (1:2,000, Cell Signaling) for 1 h at room temperature. Antibody binding was detected via Western blotting detection reagent (GE Healthcare UK limited).

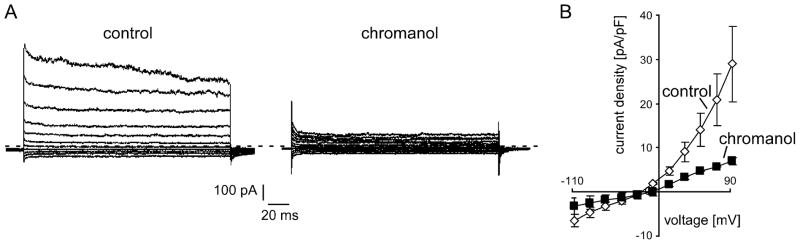

Patch-clamp experiments were performed on FRTL-5 cells 48 h after seeding at room temperature in voltage clamp, fast-whole-cell mode according to Hamill et al. [13]. The cells were continuously superfused through a flow system inserted into the dish. The bath was grounded via a bridge filled with NaCl Ringer solution. Borosilicate glass pipettes (1–3 MOhm tip resistance; GC 150 TF-10, Clark Medical Instruments, Pangbourne, UK) manufactured by a microprocessor-driven DMZ puller (Zeitz, Augsburg, Germany) were used in combination with a MS314 electrical micromanipulator (MW, Märzhäuser, Wetzlar, Germany). The currents were recorded by an EPC-9 amplifier (Heka, Lambrecht, Germany) using Pulse software (Heka) and an ITC-16 Interface (Instrutech, Port Washington, N.Y., USA). Whole-cell currents were elicited by 200 ms square-wave voltage pulses from −100 to +100 mV in 20 mV steps from a holding potential of −40 mV. All voltages were corrected for a liquid-junction potential of 8 mV. The currents were recorded with an acquisition frequency of 10 and 3 kHz low-pass filtered. The cells were superfused with a bath solution containing: 140 mM/l NaCl, 5 mM/l KCl, 1 mM/l MgCl2, 2 mM/l CaCl2, 20 mM/l glucose, and 10 mM/l HEPES/NaOH, pH 7.4. The patch-clamp pipettes were filled with an internal solution containing: 80 mM/l KCl, 60 mM/l K+-gluconate, 1 mM/l MgCl2, 1 mM/l Mg-ATP, 1 mM/l EGTA, 1 mM/l cAMP, 10 mM/l HEPES/KOH, pH 7.2. Where indicated chromanol (10 μM, Tocris Bioscience, Bristol, UK) was added to the bath solution.

Data are provided as arithmetic means±SEM, n represents the number of independent experiments. All data were tested for significance using paired or unpaired Student t test, as applicable. Only results with p<0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

Results

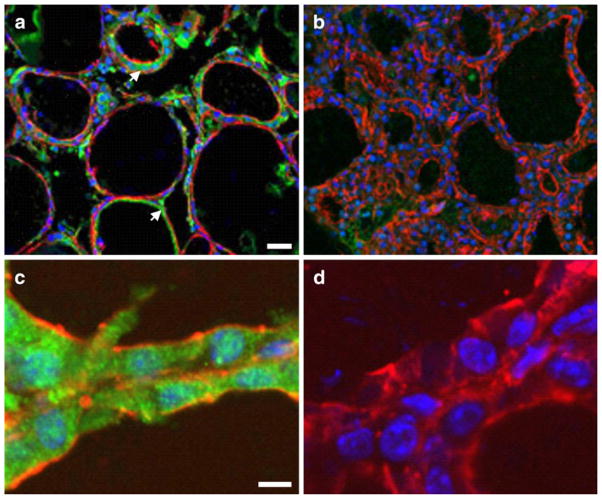

RT-PCR was employed to determine whether Kcnq1 is expressed in thyroid glands and Kcnq1 transcripts could indeed be detected in the thyroid tissue (data not shown). The intrathyroid localization of Kcnq1 was determined by immunohistochemistry via confocal microscopy. As shown in Fig. 1, Kcnq1 protein is expressed in follicular cells. The staining extends throughout the follicular cells, which may reflect Kcnq1 protein expression in vesicles or in infoldings of the cell membrane. No staining was detected in thyroid tissue from the Kcnq1-deficient mice (Kcnq1−/−), indicating that the antibody bound exclusively to Kcnq1 protein.

Fig. 1.

Expression of Kcnq1 in the thyroid gland. a–d Immunofluorescence localization of Kcnq1 in the thyroid follicular cells: A Kcnq1 specific antibody (green), a nuclear labeling with Draq5 (blue, pseudocolor—as Draq5 emits in the red spectrum) and actin staining with phalloidin (red) were used. Colocalization of Kcnq1 and actin yields yellow color. a expression of Kcnq1 in thyroid follicular cells (arrows) of WT mice. c Higher magnification of the expression of Kcnq1 in follicular cells of the thyroid gland. b, d the Kcnq1 antibody does not yield any staining in thyroid tissue from Kcnq1-deficient mice as negative controls. The scale bar in a corresponds to 20 μm in a and b and the scale bar in c corresponds to 5 μm in c and d

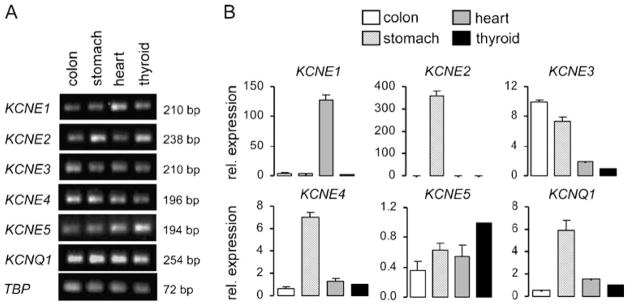

In addition we also checked the expression of KCNQ1 and all known subunits (KCNE1-5) in the human thyroid via Real-time PCR (Fig. 2). We compared the relative expression of the investigated mRNAs in the human thyroid to the expression found in human colon, stomach, and heart. Similar as in mouse thyroid gland, KCNQ1 is highly expressed in human thyroid tissue. All five beta subunits (KCNE1-5) were expressed in the thyroid, the highest expression being found for KCNE4.

Fig. 2.

Expression of KCNQ1 and KCNE1-5 in human colon, stomach heart, and thyroid tissue. KCNQ1 and KCNE1—KCNE5 mRNA expression in human colon, stomach, heart, and thyroid gland was measured by Real-Time PCR. Expression of the housekeeping gene TBP served as a calibrator and a control. Representative photographs are shown. a Gel pictures of the amplified mRNA. b The figure shows the relative expression of KCNQ1 and KCNE1-5 in human thyroid gland compared to colon, stomach, and heart

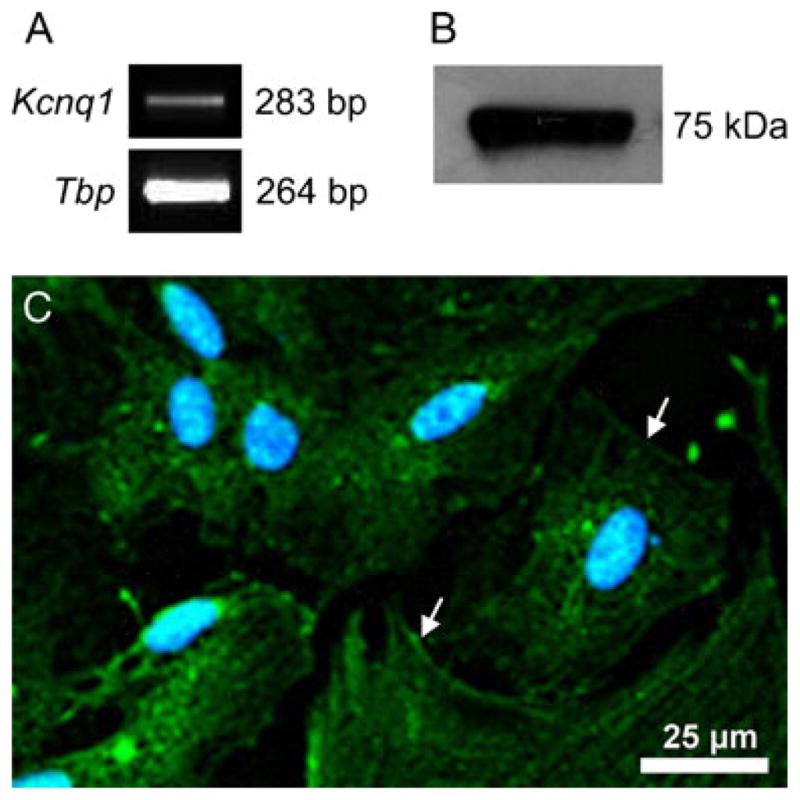

To investigate the Kcnq1 currents in thyroid cells we used the rat FRTL-5 cells. At first Kcnq1-expression in FRTL-5 cells was checked via Real-Time PCR, Western blot with cell surface biotinylation and immunocytochemistry/immunofluorescence (Fig. 3a, b, and c). All three applied methods showed a clear expression of Kcnq1 in the cells. The immunostaining confirmed that Kcnq1 is expressed both in intracellular vesicles and in the cell membrane (Fig. 3c), similar to what was observed in the thyroid follicular cells of the mouse.

Fig. 3.

Expression of Kcnq1 in FRTL-5 cells. a Real-time PCR showing Kcnq1-mRNA expression in relation to the housekeeping gene Tbp. b Western blot representing membrane expression of Kcnq1. c Confocal picture of FRTL-5 cells showing the Kcnq1-localization. Arrows mark the Kcnq1 expression in the cell membrane

Endogenous currents from FRTL-5 cells were measured using patch-clamp recording in the whole-cell configuration (Fig. 4). In accordance to a previous study [28], K+ -selective currents inhibited by a Kcnq-specific antagonist chromanol were recorded, when FRTL-5 cells were cultured in the presence of high TSH concentrations (10 mUnits/ml). The reversal potential in FRTL-5 cells was about −25 mV under control conditions and the reversal potential of the chromanol-sensitive current fraction was about −49 mV. No chromanol-sensitive currents could be measured when no TSH was added in the culture medium (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

a Representative whole-cell patch-clamp recording of K+ currents from a FRTL-5 cell under control conditions and following application of chromanol (10 μM). The currents were elicited by 200-ms depolarizing pulses ranging from −108 to +92 mV in 20-mV increments from a holding potential of −48 mV. Zero current level is indicated by the dashed line. b Mean current-voltage (I–V) relationships (n=16) of peak K+ current density in FRTL5 cells under control conditions (open symbols) and after application of chromanol (10 μM, closed symbols)

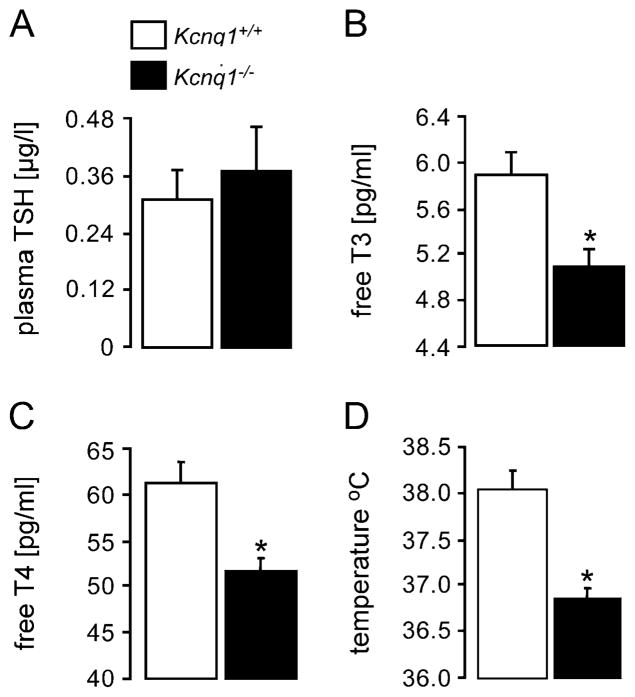

To determine the functional significance of Kcnq1, the plasma concentrations of T3 and T4 were determined in Kcnq1−/− mice and their wild-type littermates (Kcnq1+/+). As shown in Fig. 5b and c the plasma concentrations of both, T3 and T4, were indeed significantly lower in Kcnq1−/− than in Kcnq1+/+ mice, confirming that Kcnq1 deficiency leads to hypothyroidism. In theory, the decreased release of thyroid hormones in Kcnq1−/− mice could have resulted from decreased stimulation of the thyroids by the thyroid-stimulating hormone TSH. The plasma levels of TSH, tended to be higher in Kcnq1−/− compared to Kcnq1+/+ mice, a difference, however, not reaching statistical significance (Fig. 5a). TSH levels in 3-week-old mice again tended to be higher in Kcnq1−/− mice (4.0±0.1 μIU/ml, n=6) as compared to Kcnq1+/+ mice (3.5±0.3 μIU/ml, n=6), a difference again not reaching statistical significance.

Fig. 5.

Plasma concentrations of TSH, T3/T4 and body temperature in Kcnq1−/− and Kcnq1+/+ mice. Arithmetic means±SEM of plasma concentrations of a thyroid-stimulating hormone TSH (n=20–21), of b free T3 (n=7–8) and of c T4 (n=7–8) in Kcnq1-deficient mice (Kcnq1−/−, closed bars) and their wild-type littermates (Kcnq1+/+, open bars). d Arithmetic means±SEM (n=9–10) of body temperature in Kcnq1-deficient mice (Kcnq1−/−, closed bars) and their wild-type littermates (Kcnq1+/+, open bars). Asterisk (*) Significant difference (p<0.05) between Kcnq1−/− and Kcnq1+/+ mice

A key feature of hypothyroidism is decreased metabolic rate with decreased body temperature. As shown in Fig. 5d, the body temperature was indeed significantly lower in the Kcnq1−/− than in the Kcnq1+/+ mice. The body weight was similar in Kcnq1+/+ mice (22.7±1.4 g, n=7) and in Kcnq1−/− mice (21.1±1.2 g, n=7).

Discussion

The present study reveals that Kcnq1 is expressed in the cell membrane of thyroid follicular cells and plays a significant role in thyroid function. Despite the tendency of increased TSH plasma levels, the plasma concentrations of T3/T4 are lower in Kcnq1 knockout (Kcnq1−/−) mice than in their wild-type littermates (Kcnq1+/+). The hypothyroidism of the Kcnq1−/− mice results in hypothermia, reflecting a decreased metabolic rate.

Signs of hypothyroidism include alopecia, impaired hearing, bradycardia, constipation, weight gain, and weakness [15, 19]. In amphibians, T3/T4 are known to be required for the metamorphosis [6]. The phenotype of Kcnq1−/− mice includes deafness and movement disorders [4, 23], defective gastric acid secretion [23, 32], defective renal and intestinal nutrient and electrolyte transport with arterial hypotension, vitamin B12 deficiency with anemia [40], as well as enhanced insulin sensitivity [3]. Hypothyroidism could contribute to several of the disorders encountered in Kcnq1−/− mice. It is noteworthy in this respect that the coincidence of hypothyroidism and torsade de points has been reported [34]. However, as Kcnq1 is expressed in the respective tissues the phenotype of the Kcnq1−/− mice is presumably in large part secondary to the lack of Kcnq1 in the affected organs rather than the result of the moderate hypothyroidism.

In the course of this study the expression of Kcnq1 has been observed in thyroid glands and shown to form, together with Kcne2, a heteromeric K+ channel complex maintaining iodide uptake [28]. Kcne2 deficient (Kcne2−/−) offspring of Kcne2−/− dams developed impaired iodide uptake and hypothyroidism, dwarfism, alopecia, and goiter [28]. The phenotype of the Kcne2−/− offspring was in large part due to impaired maternal milk ejection of the Kcne2−/− dams and was alleviated or lacking in Kcne2−/− mice from heterozygous Kcne2+/− dams [28]. Our animals have been generated by heterozygous breeding explaining the lack of dwarfism and alopecia despite a similar impairment of T3/T4 release. Nevertheless, both mice have the hypothyroidism in common thus highlighting the importance of the Kcne2/Kcnq1 complex for proper thyroid function.

Kcne2 and Kcnq1 may influence thyroid function in two ways. On the one hand, the K+ channel presumably participates in the maintenance of the cell membrane potential and thus the electrical driving force for Na+-coupled iodide transporter NIS [5]. Lack of Kcne2/Kcnq1 may thus impair T3, T4 formation by compromising iodide uptake into the thyroid, what has indeed been shown in Kcne2−/− mice [28]. On the other hand, Kcnq1 may participate in the machinery of cell proliferation [16, 18, 24, 29, 31, 36, 37], which is critically dependent on K+ channel activity [17, 22]. Impaired cell proliferation would be expected to reduce thyroid mass. In contrast to the goiter observed in Kcne2−/− offspring from Kcne2−/− dams, the size of the thyroids is not appreciably increased in Kcnq1−/− mice (not shown). Accordingly, the goiter of Kcne2−/− offspring from Kcne2−/− dams may have been due to decreased availability of maternal iodine with subsequent stimulation of thyroid growth by TSH. The lack of increase of thyroid mass in Kcnq1−/− mice despite the similarly increased TSH levels could indicate that Kcnq1 does not only participate in the maintenance of the driving force for NIS (Slc5a5) but similarly participates in the regulation of cell proliferation. It should be kept in mind that for this latter function, Kcnq1 could in theory form heteromeric complexes with subunits other than Kcne2. The role of additional partners of KCNQ1 needs to be addressed in future studies.

In conclusion, the present study discloses a critical role of Kcnq1 in thyroid growth and function. The hypothyroidism may add to the phenotypic alterations of organ function in Kcnq1-deficient mice.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the technical assistance of E. Faber, R. Engelhardt, B. Rausch, and Dr. B. Riederer for breeding and genotyping kcnq1−/− and kcnq1+/+ mice. The manuscript was meticulously prepared by T. Loch and L. Subasic. This study was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (GK 1302) and Se460/9-6 (to U.S.).

Contributor Information

Henning Fröhlich, Department of Physiology, University of Tübingen, Gmelinstr. 5, 72076 Tübingen, Germany.

Krishna M. Boini, Department of Physiology, University of Tübingen, Gmelinstr. 5, 72076 Tübingen, Germany

Guiscard Seebohm, Department of Biochemistry I, Ruhr-University Bochum, Universitaetsstrasse 150, 44780 Bochum, Germany.

Nathalie Strutz-Seebohm, Department of Biochemistry I, Ruhr-University Bochum, Universitaetsstrasse 150, 44780 Bochum, Germany.

Oana N. Ureche, Department of Physiology, University of Tübingen, Gmelinstr. 5, 72076 Tübingen, Germany. Department of Molecular Pathology, University of Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany

Michael Föller, Department of Physiology, University of Tübingen, Gmelinstr. 5, 72076 Tübingen, Germany.

Melanie Eichenmüller, Department of Physiology, University of Tübingen, Gmelinstr. 5, 72076 Tübingen, Germany.

Ekaterina Shumilina, Department of Physiology, University of Tübingen, Gmelinstr. 5, 72076 Tübingen, Germany.

Ganesh Pathare, Department of Physiology, University of Tübingen, Gmelinstr. 5, 72076 Tübingen, Germany.

Anurag Kumar Singh, Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Endocrinology, Medical University Hannover, Carl-Neuberg-Str. 1, 30625 Hannover, Germany.

Ursula Seidler, Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Endocrinology, Medical University Hannover, Carl-Neuberg-Str. 1, 30625 Hannover, Germany.

Karl E. Pfeifer, Laboratory of Mammalian Genes and Development, NICHD/National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA

Florian Lang, Email: florian.lang@uni-tuebingen.de, Department of Physiology, University of Tübingen, Gmelinstr. 5, 72076 Tübingen, Germany.

References

- 1.Bachmann O, Heinzmann A, Mack A, Manns MP, Seidler U. Mechanisms of secretion-associated shrinkage and volume recovery in cultured rabbit parietal cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;292:G711–G717. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00416.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barhanin J, Lesage F, Guillemare E, Fink M, Lazdunski M, Romey G. K(V)LQT1 and lsK (minK) proteins associate to form the I(Ks) cardiac potassium current. Nature. 1996;384:78–80. doi: 10.1038/384078a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boini KM, Graf D, Hennige AM, Koka S, Kempe DS, Wang K, Ackermann TF, Foller M, Vallon V, Pfeifer K, Schleicher E, Ullrich S, Haring HU, Haussinger D, Lang F. Enhanced insulin sensitivity of gene-targeted mice lacking functional KCNQ1. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009;296:R1695–R1701. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90839.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Casimiro MC, Knollmann BC, Ebert SN, Vary JC, Jr, Greene AE, Franz MR, Grinberg A, Huang SP, Pfeifer K. Targeted disruption of the Kcnq1 gene produces a mouse model of Jervell and Lange-Nielsen Syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:2526–2531. doi: 10.1073/pnas.041398998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dai G, Levy O, Carrasco N. Cloning and characterization of the thyroid iodide transporter. Nature. 1996;379:458–460. doi: 10.1038/379458a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Das B, Heimeier RA, Buchholz DR, Shi YB. Identification of direct thyroid hormone response genes reveals the earliest gene regulation programs during frog metamorphosis. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:34167–34178. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.066084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dedek K, Waldegger S. Colocalization of KCNQ1/KCNE channel subunits in the mouse gastrointestinal tract. Pfluegers Arch. 2001;442:896–902. doi: 10.1007/s004240100609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Demolombe S, Franco D, de Boer P, Kuperschmidt S, Roden D, Pereon Y, Jarry A, Moorman AF, Escande D. Differential expression of KvLQT1 and its regulator IsK in mouse epithelia. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;280:C359–C372. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.280.2.C359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dremier S, Coulonval K, Perpete S, Vandeput F, Fortemaison N, Van Keymeulen A, Deleu S, Ledent C, Clement S, Schurmans S, Dumont JE, Lamy F, Roger PP, Maenhaut C. The role of cyclic AMP and its effect on protein kinase A in the mitogenic action of thyrotropin on the thyroid cell. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2002;968:106–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finsterer J, Stollberger C. Skeletal muscle involvement in congenital long QT syndrome. Neurol Sci. 2004;25:238–240. doi: 10.1007/s10072-004-0329-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grahammer F, Herling AW, Lang HJ, Schmitt-Graff A, Wittekindt OH, Nitschke R, Bleich M, Barhanin J, Warth R. The cardiac K+ channel KCNQ1 is essential for gastric acid secretion. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:1363–1371. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.24053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grunnet M, Jespersen T, MacAulay N, Jorgensen NK, Schmitt N, Pongs O, Olesen SP, Klaerke DA. KCNQ1 channels sense small changes in cell volume. J Physiol. 2003;549:419–427. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.038455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamill OP, Marty A, Neher E, Sakmann B, Sigworth FJ. Improved patch-clamp techniques for high-resolution current recording from cells and cell-free membrane patches. Pflugers Arch. 1981;391:85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00656997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heitzmann D, Grahammer F, von Hahn T, Schmitt-Graff A, Romeo E, Nitschke R, Gerlach U, Lang HJ, Verrey F, Barhanin J, Warth R. Heteromeric KCNE2/KCNQ1 potassium channels in the luminal membrane of gastric parietal cells. J Physiol. 2004;561:547–557. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.075168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jensen MV, Joseph JW, Ronnebaum SM, Burgess SC, Sherry AD, Newgard CB. Metabolic cycling in control of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008;295:E1287–E1297. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90604.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kunz L, Roggors C, Mayerhofer A. Ovarian acetylcholine and ovarian KCNQ channels: insights into cellular regulatory systems of steroidogenic granulosa cells. Life Sci. 2007;80:2195–2198. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2007.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kunzelmann K. Ion channels and cancer. J Membr Biol. 2005;205:159–173. doi: 10.1007/s00232-005-0781-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuwamura M, Okajima R, Yamate J, Kotani T, Kuramoto T, Serikawa T. Pancreatic metaplasia in the gastro-achlorhydria in WTC-dfk rat, a potassium channel Kcnq1 mutant. Vet Pathol. 2008;45:586–591. doi: 10.1354/vp.45-4-586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ladenson PW, Singer PA, Ain KB, Bagchi N, Bigos ST, Levy EG, Smith SA, Daniels GH, Cohen HD. American thyroid association guidelines for detection of thyroid dysfunction. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1573–1575. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.11.1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lan WZ, Abbas H, Lemay AM, Briggs MM, Hill CE. Electrophysiological and molecular identification of hepatocellular volume-activated K+channels. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1668:223–233. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lan WZ, Wang PY, Hill CE. Modulation of hepatocellular swelling-activated K+currents by phosphoinositide pathway-dependent protein kinase C. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2006;291:C93–C103. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00602.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lang F, Foller M, Lang KS, Lang PA, Ritter M, Gulbins E, Vereninov A, Huber SM. Ion channels in cell proliferation and apoptotic cell death. J Membr Biol. 2005;205:147–157. doi: 10.1007/s00232-005-0780-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee MP, Ravenel JD, Hu RJ, Lustig LR, Tomaselli G, Berger RD, Brandenburg SA, Litzi TJ, Bunton TE, Limb C, Francis H, Gorelikow M, Gu H, Washington K, Argani P, Goldenring JR, Coffey RJ, Feinberg AP. Targeted disruption of the Kvlqt1 gene causes deafness and gastric hyperplasia in mice. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:1447–1455. doi: 10.1172/JCI10897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morokuma J, Blackiston D, Adams DS, Seebohm G, Trimmer B, Levin M. Modulation of potassium channel function confers a hyperproliferative invasive phenotype on embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:16608–16613. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808328105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neyroud N, Tesson F, Denjoy I, Leibovici M, Donger C, Barhanin J, Faure S, Gary F, Coumel P, Petit C, Schwartz K, Guicheney P. A novel mutation in the potassium channel gene KVLQT1 causes the Jervell and Lange-Nielsen cardioauditory syndrome. Nat Genet. 1997;15:186–189. doi: 10.1038/ng0297-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nicolas M, Dememes D, Martin A, Kupershmidt S, Barhanin J. KCNQ1/KCNE1 potassium channels in mammalian vestibular dark cells. Hear Res. 2001;153:132–145. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(00)00268-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roepke TK, King EC, Reyna-Neyra A, Paroder M, Purtell K, Koba W, Fine E, Lerner DJ, Carrasco N, Abbott GW. Kcne2 deletion uncovers its crucial role in thyroid hormone biosynthesis. Nat Med. 2009;15:1186–1194. doi: 10.1038/nm.2029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roura-Ferrer M, Sole L, Martinez-Marmol R, Villalonga N, Felipe A. Skeletal muscle Kv7 (KCNQ) channels in myoblast differentiation and proliferation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;369:1094–1097. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.02.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sanguinetti MC, Curran ME, Zou A, Shen J, Spector PS, Atkinson DL, Keating MT. Coassembly of K(V)LQT1 and minK (IsK) proteins to form cardiac I(Ks) potassium channel. Nature. 1996;384:80–83. doi: 10.1038/384080a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sarzani R, Pietrucci F, Francioni M, Salvi F, Letizia C, D’Erasmo E, Dessi FP, Rappelli A. Expression of potassium channel isoforms mRNA in normal human adrenals and aldosterone-secreting adenomas. J Endocrinol Investig. 2006;29:147–153. doi: 10.1007/BF03344088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scarff KL, Judd LM, Toh BH, Gleeson PA, Van Driel IR. Gastric H(+), K(+)-adenosine triphosphatase beta subunit is required for normal function, development, and membrane structure of mouse parietal cells. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:605–618. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70453-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schroeder BC, Waldegger S, Fehr S, Bleich M, Warth R, Greger R, Jentsch TJ. A constitutively open potassium channel formed by KCNQ1 and KCNE3. Nature. 2000;403:196–199. doi: 10.1038/35003200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shojaie M, Eshraghian A. Primary hypothyroidism presenting with Torsades de pointes type tachycardia: a case report. Cases J. 2008;1:298. doi: 10.1186/1757-1626-1-298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sugimoto T, Tanabe Y, Shigemoto R, Iwai M, Takumi T, Ohkubo H, Nakanishi S. Immunohistochemical study of a rat membrane protein which induces a selective potassium permeation: its localization in the apical membrane portion of epithelial cells. J Membr Biol. 1990;113:39–47. doi: 10.1007/BF01869604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Trinh NT, Prive A, Kheir L, Bourret JC, Hijazi T, Amraei MG, Noel J, Brochiero E. Involvement of KATP and KvLQT1 K+channels in EGF-stimulated alveolar epithelial cell repair processes. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;293:L870–L882. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00362.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsevi I, Vicente R, Grande M, Lopez-Iglesias C, Figueras A, Capella G, Condom E, Felipe A. KCNQ1/KCNE1 channels during germ-cell differentiation in the rat: expression associated with testis pathologies. J Cell Physiol. 2005;202:400–410. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Unoki H, Takahashi A, Kawaguchi T, Hara K, Horikoshi M, Andersen G, Ng DP, Holmkvist J, Borch-Johnsen K, Jorgensen T, Sandbaek A, Lauritzen T, Hansen T, Nurbaya S, Tsunoda T, Kubo M, Babazono T, Hirose H, Hayashi M, Iwamoto Y, Kashiwagi A, Kaku K, Kawamori R, Tai ES, Pedersen O, Kamatani N, Kadowaki T, Kikkawa R, Nakamura Y, Maeda S. SNPs in KCNQ1 are associated with susceptibility to type 2 diabetes in East Asian and European populations. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1098–1102. doi: 10.1038/ng.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vallon V, Grahammer F, Richter K, Bleich M, Lang F, Barhanin J, Volkl H, Warth R. Role of KCNE1-dependent K+ fluxes in mouse proximal tubule. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12:2003–2011. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V12102003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vallon V, Grahammer F, Volkl H, Sandu CD, Richter K, Rexhepaj R, Gerlach U, Rong Q, Pfeifer K, Lang F. KCNQ1-dependent transport in renal and gastrointestinal epithelia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:17864–17869. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505860102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van Tol BL, Missan S, Crack J, Moser S, Baldridge WH, Linsdell P, Cowley EA. Contribution of KCNQ1 to the regulatory volume decrease in the human mammary epithelial cell line MCF-7. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;293:C1010–C1019. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00071.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wangemann P. Supporting sensory transduction: cochlear fluid homeostasis and the endocochlear potential. J Physiol. 2006;576:11–21. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.112888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yasuda K, Miyake K, Horikawa Y, Hara K, Osawa H, Furuta H, Hirota Y, Mori H, Jonsson A, Sato Y, Yamagata K, Hinokio Y, Wang HY, Tanahashi T, Nakamura N, Oka Y, Iwasaki N, Iwamoto Y, Yamada Y, Seino Y, Maegawa H, Kashiwagi A, Takeda J, Maeda E, Shin HD, Cho YM, Park KS, Lee HK, Ng MC, Ma RC, So WY, Chan JC, Lyssenko V, Tuomi T, Nilsson P, Groop L, Kamatani N, Sekine A, Nakamura Y, Yamamoto K, Yoshida T, Tokunaga K, Itakura M, Makino H, Nanjo K, Kadowaki T, Kasuga M. Variants in KCNQ1 are associated with susceptibility to type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1092–1097. doi: 10.1038/ng.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]