Abstract

The personalized medicine revolution is occurring for cancer chemotherapy. Biomarkers are increasingly capable of distinguishing genotypic or phenotypic traits of individual tumors, and are being linked to the selection of treatment protocols. This review covers the molecular basis for biomarkers of response to targeted and cytotoxic lung and bladder cancer treatment with an emphasis on platinum-based chemotherapy. Platinum derivatives are a class of drugs commonly employed against solid tumors that kill cells by covalent attachment to DNA. Platinum–DNA adduct levels in patient tissues have been correlated to response and survival. The sensitivity and precision of adduct detection has increased to the point of enabling subtherapeutic dosing for diagnostics applications, termed diagnostic microdosing, prior to the initiation of full-dose therapy. The clinical status of this unique phenotypic marker for lung and bladder cancer applications is detailed along with discussion of future applications.

Advances in genomic sequencing and molecular marker identification during the last decade have clearly demonstrated that cancer is a heterogeneous disease both at the macroscopic patient level and at the microscopic cellular level [1]. During cancer development and progression, alterations in signaling pathways disrupt the normal function of cells [2]. Cancer is inherently a disease of genetic progression, as observed by specific and progressive molecular changes that result in increasingly severe histopathological phenotypes. These changes occur as a result of genomic alterations that include mutations, deletions, amplifications, genome rearrangements and epigenetic alterations of gene expression. Furthermore, nongenetic (phenotypic) heterogeneity, due to factors such as cancer stem cells and abnormalities in the tumor microenvironment, is likely a major contributor to resistance [1]. This view of cancer as a heterogeneous disease has prompted an enormous academic and commercial effort to identify patient- and tumor-specific molecular markers so that a personalized cancer treatment protocol can be identified that has the potential to arrest tumor progression and increase survival compared with a ‘one size fits all’ paradigm that is quickly becoming obsolete.

The heterogeneous nature of cancer tumors presents a substantial barrier to drug development. At least 90% of new oncology drugs fail to attain regulatory approval, often in late-stage clinical evaluation [3]. While some of the reasons for failure are straight forward, such as inadequate efficacy and unexpected safety issues, patient- and tumor-specific attributes such as drug resistance and suboptimal drug regimens and dosing schedules often confound outcomes of clinical trials. This has prompted drug developers to begin including ‘tumor type’ patient selection criteria based upon biomarkers as a mechanism to reduce the risk of clinical failure, and is also driving the trend for co-development of companion diagnostic assays.

The heterogeneity of tumor cells also confounds clinical management. When initial effective therapeutic intervention based upon a defined molecular target is found, it is usually transient with subsequent clonal selective proliferation of residual tumor cells resistant to the initial therapeutic drug. In the last decade, multiple different treatment protocols consisting of drug cocktails of two or three different drugs have been extensively evaluated in the clinical setting for different cancer types. Each of the drugs in the cocktail are selected to have a different molecular target, thereby reducing the risk of clonal selection based upon tumor cell resistance to one drug only. In these combination therapies, protocols often use a DNA alkylating/crosslinking agent, such as one of the platinum-based drugs (cisplatin, carboplatin or oxaliplatin), in combination with other drugs [4–6]. The other drugs can include one of the antimitotics (paclitaxel, docetaxel or vinorelbine), a chain terminating nucleoside analog, such as gemcitabine, or a topoisomerase inhibitor, such as irinotecan. More recently, EFGR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), including gefitinib or erlotinib, have also been used in combination therapy or as a second-line single agent treatment after failure of the first-line combination therapy. Erlotinib and gefitinib were developed as reversible and highly specific small-molecule TKIs that competitively block the binding of adenosine triphosphate to its binding site in the tyrosine kinase domain of EGFR, thereby inhibiting autophosphorylation and blocking downstream signaling. Erlotinib and gefitinib appear to be especially effective in tumors with gene mutations that activate EGFR. Such tumors may become dependent on the activity of the EGFR pathway for their survival [7]. Crizotinib was recently approved by the US FDA as the first and only targeted antitumor agent for locally advanced or metastatic ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). The companion diagnostic test, Abbott Molecular’s Vysis ALK Break Apart fluorescent in situ hybridization Probe Kit identifies the ALK fusion gene that the drug targets. The ALK fusion gene – comprising portions of the EML4 gene and the ALK gene – is present in approximately 3–5% of all patients with NSCLC, and is believed to be a key oncogenic driver that contributes to cell proliferation and tumor survival [201].

The extensive molecular analysis and improved understanding of cancer biology in recent years has led to an extended exploration of biomarkers, with the double goal of identifying factors that have an impact on disease outcome regardless of the treatment (prognostic factors) and those that can predict the activity of a specific agent (predictive factors). The acquisition of biomarker data in the oncology setting is becoming an indispensable activity for individualized treatment decisions by physicians and patients. The present paper provides an overview of some of the predictive biological markers that are impacting clinical decision-making for lung and bladder cancer patients as well as a focus on the use of accelerator MS (AMS) to develop platinum-based drug–DNA alkylation products as biomarkers of response to platinum-based chemotherapy. Although extensive reviews have been published that cover the biomarkers described herein, we will summarize many of the key concepts and results, and will emphasize recently published data when possible [8–15].

Lung & bladder cancers: background & treatments

The prevalence of lung cancer today is now second only to that of prostate cancer in men and breast cancer in women. Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related mortality in both men and women not only in the USA but also throughout the world. In 2012, it was estimated that the disease would cause approximately 160,000 deaths in the USA – more than colorectal, breast, and prostate cancers combined [16]. Two major types of lung cancer are small-cell lung cancer (15% of cases) and NSCLC (85% of cases), including particularly adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma.

As with most cancers, a staging system exists to classify NSCLC upon presentation, and to guide the physician and patient in selecting the appropriate therapeutic modality. The tumor, node, metastasis system is used to segregate the cancer into one of four stages. This staging system varies from stage I (localized tumor of a defined size range), to stage II (early locally advanced cancer), to stage III (late locally advanced cancer), and finally to stage IV (metastasized cancer). Lung cancer is often insidious, and it may produce no symptoms until the disease is well advanced. Consequently, most lung carcinomas are diagnosed at an advanced stage, conferring a poor prognosis. The overall 5-year survival for all stages of NSCLC remains at 15% [17]. The choice of therapy is dictated mostly by the cancer type, the stage of the disease and the current health of the patient. Treatment primarily involves surgery, chemotherapy or radiation therapy. Surgical resection remains the mainstay of treatment for all patients with stage I and II NSCLC. Approximately 20–30% of NSCLC patients are eligible for surgical resection on the basis of the stage of the disease and medical fitness [18]. In this subgroup, the overall survival ranges from 67% for stage IA to 39% for stage IIB [19]. The role of surgery for stage III disease is controversial. Since most lung cancers cannot be cured with currently available therapeutic regimes (particularly stage III and IV cancers), palliative care utilizing chemotoxic agents and/or targeted therapy to slow down the progression of the cancer is often the recommended treatment.

A number of chemotherapeutic regimens can be used to treat NSCLC. These are usually reserved for higher stages of lung cancer, as adjuvant therapy after surgery, or as neoadjuvant therapy before surgery. Neoadjuvant therapy is performed to treat micrometastatic disease present at diagnosis and to make the tumor smaller so that surgery will be easier or more effective. Adjuvant therapy is performed to kill cancer cells that may have been missed in the surgery or spread from the primary tumor.

The standard of care in the treatment of NSCLC is to use a platinum-based chemotherapeutic agent, especially in advanced disease. Platinum-based chemotherapy drugs have been recognized as an important group of cytotoxic antitumor agents because of their activity against many human malignancies, including testicular, ovarian, cervical, bladder, head-and-neck, and lung cancers. However, many patients are either intrinsically resistant or eventually develop resistance to treatment and relapse. Although testicular cancer has a cure rate of approximately 80% for this therapy, most other cancer types do not respond as well, which has prompted efforts to develop tests that can predict platinum-based drug resistance. Less than 30% of patients with metastatic NSCLC have a response to platinum-based chemotherapy. Even with the addition of newer agents, such as bevacizumab, to chemotherapy, the median overall survival of patients with metastatic NSCLC remains approximately 1 year, and only 3.5% of patients with metastatic NSCLC survive 5 years after diagnosis [20]. Most studies have shown that two agents are better than one. Three agents used in combination do not provide much additional benefit but do cause a number of additional, undesirable side effects. Therefore, chemotherapy regimens usually include two drugs. The combinations of cisplatin or carboplatin with another cytotoxic agent such as paclitaxel, docetaxel, gemcitabine, vinorelbine or irinotecan, produce similar response rates of approximately 30–40% and a median survival time of approximately 1 year for NSCLC [21]. Many patients (53–68%) developed grade 4 life-threatening toxicity, and 4–6% patients die from the platinum doublet regimens. Three-drug combinations of the commonly used chemotherapy drugs do not result in superior survival and are more toxic than two-drug combinations [22–24]. Cisplatin and carboplatin yield similar improvements in outcome, but with different toxic effects. Some, but not all, trials and meta-analyses of trials suggest that outcomes with cisplatin may be superior, although with a higher risk of certain toxicities such as nausea and vomiting [25].

Bladder urothelial cancer is the fourth most common cancer in males and ninth in females and a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. In the USA, approximately 70,530 individuals were diagnosed with bladder cancer in 2010 with 14,680 mortalities [26]. Most bladder cancers in the developed world are of urothelial origin (transitional cell carcinoma), arising from the epithelial lining. Bladder cancers are staged based on the extent of disease progression, ranging from non-myoinvasive (stage I), invasion into bladder wall (stage II), invasion to the tissue or local other organs outside bladder (stage III), and invasion to abdominal or pelvic wall or metastasis to lymph nodes or distant organs (stage IV). Approximately 70–80% of newly diagnosed bladder cancers are noninvasive. The initial treatment of noninvasive cancer involves surgical resection followed by adjuvant therapy. As many as 70% of noninvasive cancers recur, necessitating life-long surveillance, and up to 25% will progress to more advanced disease [27]. Bladder cancer is, therefore, the most expensive cancer to treat owing the invasive multiyear surveillance by cystoscopy that is required after resection of the tumor tissue. For patients with muscle-invasive, nonmetastatic disease (stages II and III), radical cystectomy with bilateral pelvic lymph node dissection remains the mainstay of treatment. Recurrence can be frequent even after surgery. For example, approximately 50% of patients with deep, muscle-invasive disease will develop metastatic disease even after surgery [28]. Thus, systemic platinum-based chemotherapy, either in a neoadjuvant or adjuvant setting, is considered a component of the standard care for this disease. Platinum-based chemotherapy after surgery can reduce recurrence, but since only 50% of patients respond, many skip this potentially lifesaving option. Stage IV bladder cancer is usually treated with chemotherapy, but the median survival even with the best chemotherapy is often only approximately 14 months [29].

As discussed above, platinum-based therapies are presently and will likely remain the standard of care for both lung (NSCLC) and bladder (transitional cell carcinoma) cancers as either an adjuvant, neoadjuvant or pallitative treatment. The responses rate in unselected patient populations with either of these cancer types is poor (~30% for NSCLC and 50% for transitional cell carcinomas). With such low response rates, clinicians are faced with several questions before selecting a treatment regime. First, is the patient’s tumor sufficiently aggressive to consider neoadjuvant or adjuvant therapy? Second, if platinum-based chemotherapy is considered, will the tumor be likely to respond to a platinum drug? And third, what is the best combination drug for use with a platinum compound to consider for this particular cancer? Choice of the optimal drug combination is critical since efficacy and side effects are interrelated. Many side effects by themselves lead to non-compliance, drop out and dose down-titration in therapy, which compromises efficacy. Molecular biomarkers are emerging as useful tools to answer the questions above and assign patients to appropriate treatments.

The development and acceptance of biomarkers for use in the selection of the most appropriate treatment for an individual patient is following a structured path. Historically, biomarkers are identified through academic studies, usually using pedigreed tumor cell lines and tumor xenografts in animal models. Assays for the biomarker are then refined for clinical use. Retrospective biomarker analysis of tumor samples collected in drug therapeutic studies of unselected patients has identified subpopulations on the basis of biomarker status for which enhanced beneficial outcomes are observed (response rates, progression-free survival or overall survival). To gain acceptance among practicing physicians and regulatory bodies, prospective clinical studies are then conducted in which arms of the study are differentially selected and treated on the basis of biomarker status. These studies are cancer-type specific and designed to separately address the neoadjuvant, adjuvant or systemic settings, including maintenance therapy. Favorable outcome leads to regulatory claims for use of the drug in combination with biomarker patient selection. Ultimately, incorporation into standard of care is achieved when oncology professional organizations such as the American Association of Clinical Oncologists or the National Comprehensive Cancer Network incorporate use of the biomarker into their cancer treatment guidelines and disseminate the guidelines to community oncologists.

Our interest in lung and bladder cancer arises from the enormous social impact of these diseases from a human health perspective as well as the economic cost to the healthcare system, the importance of platinum combination therapies in both of these cancers, and the need for better patient selection due to the poor response rate in both of these cancer settings. Comprehensive reviews of the status of biomarker development and clinical qualification for NSCLC and bladder cancer have recently appeared, as have reports of platinum drug quantification in tissues [30–32]. Conventional prognostic factors obtained from histological staging are useful for predicting outcomes from surgery and the risk of reoccurrence, but are inadequate in predicting response to therapy. Since platinum combination therapy is common to both cancers, they share some common predictive biomarkers. The more advanced predictive biomarkers being evaluated for lung and bladder cancers, and their molecular basis, are discussed below.

Predictive biomarkers based upon gene expression & mutation

Predictive biomarkers for platinum-based chemotherapy

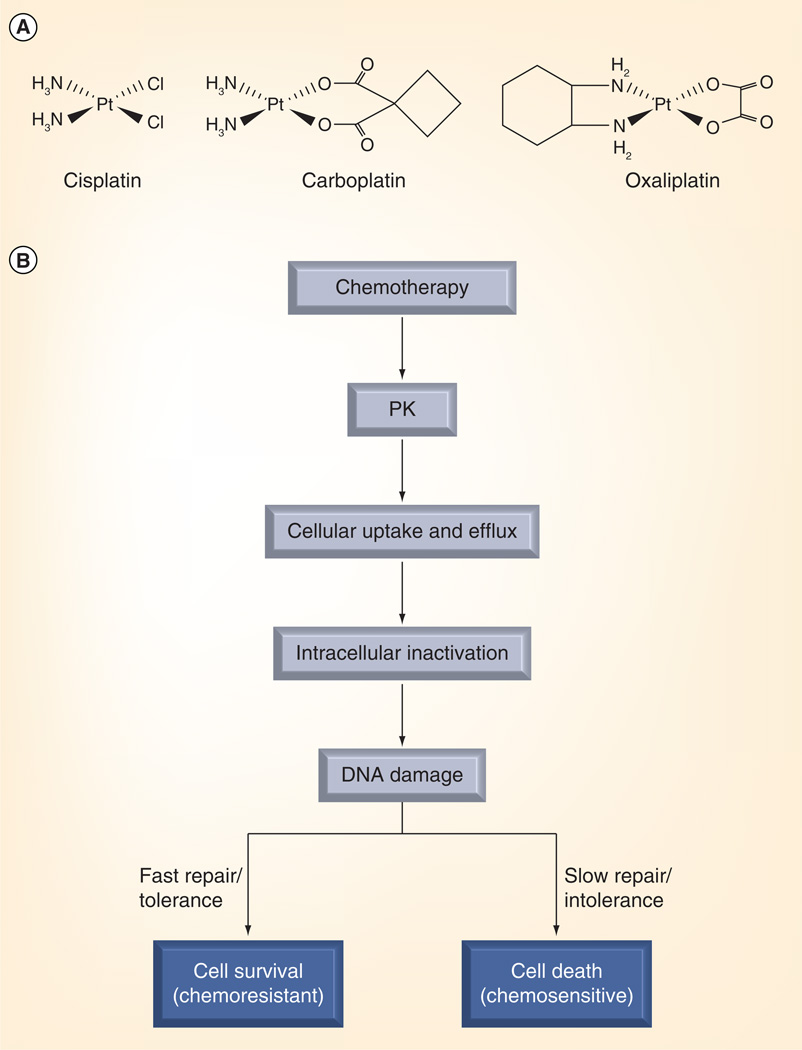

Cisplatin and carboplatin are the two most frequently used platinum agents for chemotherapy (Figure 1A). These compounds are administered intravenously and can be taken up into cells via active transport or by passive diffusion (Figure 1B) [33]. Platinum-based compounds induce their cytotoxic effects by direct covalent binding as both monoadducts and intra- or inter-strand crosslinks, which in turn, interfere with DNA transcription and replication. Although these adducts are the target of repair pathways, their accumulation ultimately induces the apoptotic response and cell death [34]. Biomarker investigation has, therefore, concentrated on repair molecules associated with platinum adducts.

Figure 1. Platinum-based drug structures and mechanistic basis for biomarker development.

(A) Chemical structures of cisplatin, carboplatin and oxaliplatin. (B) Metabolism and cellular response to platinum-based chemotherapy and drug resistance.

Reproduced with permission from [185] © Wiley.

ERCC1

There are at least four repair mechanisms known to correct the damage to DNA. These are base excision repair, mismatch repair, double-strand break repair and the nucleotide excision repair (NER) pathways. Within these mechanisms, the NER system is essential to repair ‘bulky damage’ – large groups consisting of multiple atoms covalently bound to DNA called adducts [35]. Removal of platinum–DNA adducts is mediated by the NER pathway, which is a coordinated process involving at least 20 proteins [36]. It is essentially a ‘cut-and-paste’ repair mechanism [37]. The rate-limiting step in the NER pathway is damage recognition and excision. ERCC1 is the lead enzyme in this process of recognition and excision. ERCC1 forms a heterodimer with the xerodermapigmentosum group F protein and excises the nucleotide segment containing the adducts in coordination with an accessory protein called XPG. For both lung [38] and bladder [39] cancer, most studies in the advanced clinical setting using a RT-PCR assay for mRNA expression have shown an improved outcome for platinum-treated patients with low ERCC1 levels. Expression levels of ERCC1 assessed by immunohistochemical staining of ERCC1 protein have confirmed these findings and also suggest a prognostic role for this marker as well [40]. High tumor ERCC1 protein expression was associated with a significantly longer survival, while low ERCC1 expression correlated with improved response to platinum-based chemotherapy. This apparent contrast is consistent with improved genomic stability that may accompany higher ERCC1 expression as a prognostic factor, while low expression supports a limited ability for cells to remove platinum–DNA damage during chemotherapy as a predictive factor. Although cisplatin and carboplatin both result in bulky DNA-distorting adducts and elicit NER, platinum treatment also induces interstrand crosslinks that are repaired by the Fanconi pathways during S phase [41]. Furthermore, other cellular repair mechanisms, such as recombination or mismatch repair, can affect antitumor efficiency of cisplatin [42]. Therefore, ERCC1 has some limitations as a biomarker in completely evaluating all relevant pathways involved in repair of platinum-induced DNA damage.

BRCA1

BRCA1 is a tumor-suppressor gene. Its protein product is found in the nucleus where it associates with other nuclear proteins to create a surveillance complex that is involved with transcription and DNA repair of double-strand breaks [43]. Low expression of BRCA1 mRNA is associated with increased sensitivity to cisplatin-based therapy in lung cancer [44]. Similar increased sensitivity in a low background of BRCA1 mRNA expression has been observed in the neoadjuvant setting for bladder cancer [45]. Increased copy number of the wild-type BRCA1 gene also appears to confer significantly poorer survival, suggesting that lower levels of BRCA1 are predictive of a better response to platinum treatment [46].

It should be pointed out that ERCC1 and BRCA1 biomarkers are in vitro surrogate measurements that are associated with clinical outcome following platinum treatment. While it is assumed that decreased tumor repair capability will lead to increased platinum–DNA adduct formation, no such correlation has yet to be established in the clinical setting.

p53

The p53 protein, a tumor-suppressor gene product, is one of the most extensively studied proteins in cancer. It activates DNA repair proteins. When DNA is damaged, it functions as a checkpoint regulator holding the cell cycle at G1/S allowing for completion of DNA repair, and it also plays a role in initiating apoptosis [47]. Alterations in the p53 gene lead to a loss of its tumor-suppressor function and to genetic instability, in part due to a longer half-life, and is thought to be a key event in carcinogenesis. Expression levels and genotypic mutation identification have potential prognostic value in assessing tumor progression. The predictive value of p53 as a biomarker in lung cancer may reside in specific mutation analysis. The presence of a mutant p53 genotype was highly indicative of resistance to induction chemotherapy with cisplatin (p < 0.002) in a 35-patient study [48]. In the bladder setting, a retrospective analysis of patients treated with adjuvant therapy found that patients with p53 alteration had increased sensitivity to treatment and had more benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy [49]. A Phase III clinical trial designed to further evaluate this finding was halted and, therefore, inconclusive about p53 as a predictive biomarker [50].

Gemcitabine biomarkers

Gemcitabine is often used as the second drug along with cisplatin or carboplatin in first-line doublet therapy for lung and bladder cancers. Gemcitabine is a fluorinated analogue of deoxycytidine. It is a potent and specific pyrimidine antimetabolite. It is introduced into cells by means of active carriers, including the hENT1. Upon uptake into the cells, gemcitabine can be either deaminated to an inactive form, 2,2-difluorodeoxyuridine by cytidinedeaminase, or phosphorylated by deoxycytidine kinase to dFdC-5-monophosphate and to the active diphosphate and triphosphate metabolites. While dFdC-5-diphosphate blocks the activity of ribonucleotide reductase (RR), an enzyme essential for the production of deoxyribonucleotides by irreversible binding to its active site, dFdC-5-triphosphate is incorporated into DNA and leads to early termination of DNA synthesis [51].

hENT1

Preclinical cell-culture studies established that hENT deficiency is associated with gemcitabine resistance [52]. Protein expression of hENT1 by immunohistochemical staining has been evaluated in metastatic tumors of NSCLC and bladder patients. Correlation of hENT1 levels with resistance is unclear in the NSCLC setting [53], while in a small study report on bladder cancer there appears to be a better response rate with patients that had higher hENT1 protein expression [54].

RRM1

RR has a key role in DNA synthesis and repair by catalyzing the conversion of ribonucleotides to deoxyribonucleotides. RR consists of two subunits: RR subunits 1 and 2 (RRM1 and RRM2). High expression of the regulatory subunit RRM1 is a major determinant of gemcitabine resistance in NSCLC [55]. RRM1 may have a prognostic role as well, since increased expression of RRM1 is associated with increased survival of patients with resected NSCLC [56]. RRM1 may also have a predictive role the bladder setting. In one study report, in which patients received cisplatin/gemcitabine with or without paclitaxel, there was a trend for longer time to progression in tumors with low RRM1 expression [39].

Antimitotic biomarkers

Taxanes are a class of compounds that bind to β-tubulin, resulting in stabilization of microtubules and inhibition of their depolymerization. This leads to chronic activation of the spindle-assembly checkpoint ultimately causing mitotic arrest [57]. Paclitaxel and docetaxel are examples of this class that are often used with a platinum agent in a doublet therapy for lung or bladder cancers. Toxicity is a clinical issue with these compounds, therefore information from a biomarker correlated with their beneficial use is needed. Vinorelbine, also an antimitotic, acts in a different manner by preventing microtuble assembly and is sometimes used synergistically with taxanes. β-tubulin is the target of the taxanes and has been investigated extensively as a biomarker for this class of compounds. In vitro and retrospective clinical studies of lung cancer have shown that overexpression of β-tubulin III is associated with resistance to taxanes [58].

EGFR biomarkers

The EGFR is a transmembrane receptor with an intracellular tyrosine kinase domain that belongs to the ErbB family, which includes four structurally related receptor kinases: EGFR/HER1/Erb1, HER2/Erb2, HER3/Erb3, and HER4/Erb4 [59]. The receptor can be activated as a result of ligand-binding or via ligand-independent mechanisms, such as specific gene mutations, gene amplification, or overexpression. EGFR activation results in dimerization with subsequent autophosphorlation of tyrosine residues in the kinase domain. This phosphorlation cascades downstream through additional pathways ultimately affecting cell proliferation and survival. EGFR can form dimers with itself (homodimerization) or with other ErbB family receptors (heterodimerization). The various dimers have differential effects on signaling pathways. EGFR activation is known to drive the development of multiple solid tumor types. EFGR signaling can become dysregulated with constitutive activation in cancer cells through:

-

▪

Overexpression of ligands that bind to EGFR;

-

▪

The presence of excess copies of the EFGR protein on the cell surface due to gene amplification or overexpression;

-

▪

EFGR genetic mutations that enable downstream signaling pathways in the absence of ligand binding.

As a result, several targeted therapeutic agents have been created to interfere with EGFR activity. Small molecules – TKIs – that inhibit the intracellular EFGR tyrosine kinase domain through reversible (gefitinib and erlotinib) or irreversible binding to the ATP site have been developed. Additionally, monoclonal antibodies (cetuximab and panitumumab) directed against the extracellular portion of the receptor and that interfere with dimerization are approved for use in selected cancers. As these drugs interfere with the growth and spread of new cancer cells, they are viewed as targeted antitumor therapeutics as opposed to cytotoxic drugs.

EGFR expression

Although EGFR is constitutively expressed in many normal epithelial tissues, including skin and hair follicles, overexpression of EGFR as measured by immunohistochemical staining is common in many cancers. Anti-EGFR targeted therapies are logically expected to be beneficial in tumors positively expressing EGFR protein. The initial FDA approvals for cetuximab and panitumumab treatments were limited to EGFR-expressing metastatic colorectal carcinomas. This limitation highlights the predictive role of this expression biomarker for these treatments in colon cancer. For NSCLC, expression of EGFR protein has generated conflicting results for both EGFR TKIs [60–66] and cetuximab [67–73].

EGFR activating mutations & TKIs

Gefitnib’s original FDA approval in 2003 for NSCLC was based upon a small percentage of the unselected NSCLC population benefiting from the treatment. It now appears that EGFR genotyping is a predictor of benefit. Retrospective genotyping of tumor samples from multiple nonselective NSCLC clinical trials have identified somatic gain-of-function mutations in the EGFR gene that are associated with increased response to the TKIs gefitnib or erlotinib [74–76]. The vast majority of EGFR mutations are observed as exon 19 deletions or by the L858R substitution in exon 21. These mutations have a high incidence (30–50%) in tumors originating from patients having the following characteristics: female, Asian ethnicity, adenocarcinoma histology; and no history of smoking. The incidence of these mutations in Western populations is considerably less (10%). Prospective trials in NSCLC patients selected for EGFR gene mutations have confirmed the retrospective data and demonstrate that TKI response rates as high as 75% are achievable, with progression-free survival of 9 months and overall survival of 20 months [77–85]. Gefitnib was approved in Europe by the European Medicines Agency only for NSCLC harboring an EGFR mutation.

EGFR gene amplification

Amplification of the EGFR gene is commonly measured by fluorescent in situ hybridization. Multiple studies have shown a correlation between increased EGFR gene copy number and increased EGFR TKI sensitivity [70,86,87]. This correlation may be due, in part, to EGFR mutations. There seems to be an association between increased EGFR copy number and EGFR mutations [88]. EGFR gene copy number as a predictor of response to cetuximab for NSCLC is not as clear [67,68,73,89,90].

Predictors of resistance to anti-EGFR agents

In addition to the identification of markers that predict response to anti-EGFR agents, markers that predict anti-EGFR resistance are also emerging. Since EGFR activation results in a cascading response through additional pathways, mutations resulting in constitutive activation of a downstream pathway can render the anti-EGFR agent uneffective. The KRAS G protein is an important downstream responder to EGFR activation. In metastatic colorectal carcinomas, KRAS mutational status is predictive of nonresponse to cetuximab and panitumumab [91,92]. Clinical benefit is largely limited to those patients whose tumors contain KRAS wild-type. In 2009, the FDA updated the labels for use of these anti-EGFR monoclonal antibodies for metastatic colorectal cancers to include KRAS mutational status. Contrary to the colorectal cancer situation, KRAS mutations do not appear to be predictive of cetuximab benefit in NSCLC [93,94]. TKI benefit also appears to be independent of KRAS mutational status in NSCLC. Both preclinical data with gefitinib [95] and clinical data with erlotinib [96], support the notion that KRAS mutations are not predictive of TKI response.

While some gene mutations in the kinase domain of EGFR predict sensitivity to TKIs, others are predictive of resistance. Intrinsic resistance has been observed with the rare T790M mutation [79]. The T790M substitution has been shown to increase ATP affinity at the ATP binding site in the kinase domain, rendering TKIs less effective [97].

EGFR-mutant tumors in patients that are initially responsive to TKI therapy will ultimately progress as a result of acquired resistance. The T790M substitution is acquired as a secondary mutation in approximately 50% of resistant tumors after TKI therapy [98]. The next generation of TKIs will bind irreversibly to the ATP site and have the potential to overcome this resistant phenotype. Afatinib is an irreversible inhibitor targeting EGFR and HER2 that has activity in erlotinib- and gefitinib-resistant lung cancer models [99]. PF00299804 is another irreversible pan ErbB kinase inhibitor with activity in lung cancer cells that have a geftinib-resistant EGFR or HER2 mutation [100]. Both of these irreversible TKIs are currently being evaluated for clinical effectiveness.

Platinum drug–DNA adducts contribute to cytotoxicity & are potential prognostic & predictive biomarkers

Current diagnostics on the market for predicting lung cancer resistance to platinum-based chemotherapy are based on in vitro assays that have so far failed to effectively identify alternative treatments for resistant tumors. There are no diagnostic tests available for predicting the response of bladder cancer to any type of chemotherapy. Cisplatin and carboplatin are well-established agents used clinically against a broad range of malignancies, including bladder and lung [101]. The introduction of oxaliplatin into clinical practice has extended the role of this class of drugs, particularly for cisplatin-refractory colon cancers [102].

Although the primary mode of platinum drug cytotoxicity is through covalent modification of cellular DNA [103], additional effects related to reactions with proteins and antioxidants, such as glutathione and thioredoxin, likely both mitigate efficacy and contribute to drug resistance as part of a complex interplay of numerous mechanisms (Figure 1B) [104]. Despite an increasing understanding of the molecular mechanisms by which platinum–DNA adducts interact with cellular processes, we still have a relatively poor understanding of the reasons for interpatient variation in clinical response and toxicity [105–107]. In particular, little is known about the concentration of platinum–DNA adducts formed in tissues, especially in tumors, and the relationship between adducts and clinical outcome.

Measurement of the propensity for tumor and other tissues to form and repair drug–DNA adducts may provide useful biomarkers in patients, particularly if it can be implemented prior to the initiation of chemotherapy. Clinical studies investigating adduct levels monitored during therapy (i.e., the ratio of drug–DNA adducts to total DNA) and relationships to response and/or PK have overwhelmingly relied on peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and occasionally buccal cells as surrogates of tumor tissue owing to ease of collection compared with tumor biopsy samples. Measurements on tumor biopsies are challenging due to inherently low adduct levels and difficulties in obtaining biopsies at multiple time points, when the resulting data would be most informative.

Several reports have documented associations between drug–DNA adduct levels in surrogate tissues and clinical response and toxicity [108–114]. The platinum–DNA adduct formation in PBMCs was found to more predictive for tumor response to platinum-based therapy than previous platinum-based therapy, stage of disease, histological type and tumor grading [109]. Recently, a significantly better disease-free survival was reported for cisplatin-treated head-and-neck carcinoma patients with higher adduct levels [115]. The feasibility of intra-individual dose escalation of cisplatin based on platinum–DNA adduct levels has been shown in two clinical trials in patients with head-and-neck cancer [116] and NSCLC [117]. However, not all investigators found a relationship between surrogate tissue adduct levels and tumor response. It has been speculated that the technique of the adduct measurement, the tumor types investigated, and medication factors could have influenced the adduct levels and led to conflicting results [118,119].

Although the most obvious causal link between drug–DNA adducts in cells and cytotoxicity is due to variations in PK, other factors such as cellular drug uptake, DNA repair and apoptosis probably contribute substantially to variations patient outcomes (Figure 1). For example, platinum–DNA adduct levels in PBMCs were positively related to dose and area under the curve (AUC) for carboplatin in a dose-escalation setting [120]. However, two studies with cisplatin [121] or carboplatin [122] demonstrated a poor correlation between drug AUC and platinum–DNA adduct levels in PBMCs. These data indicate that inter-individual variation in factors other than PK may significantly affect adduct levels in PBMCs, which justifies larger predictive biomarker studies on surrogate tissues in the clinical oncology setting.

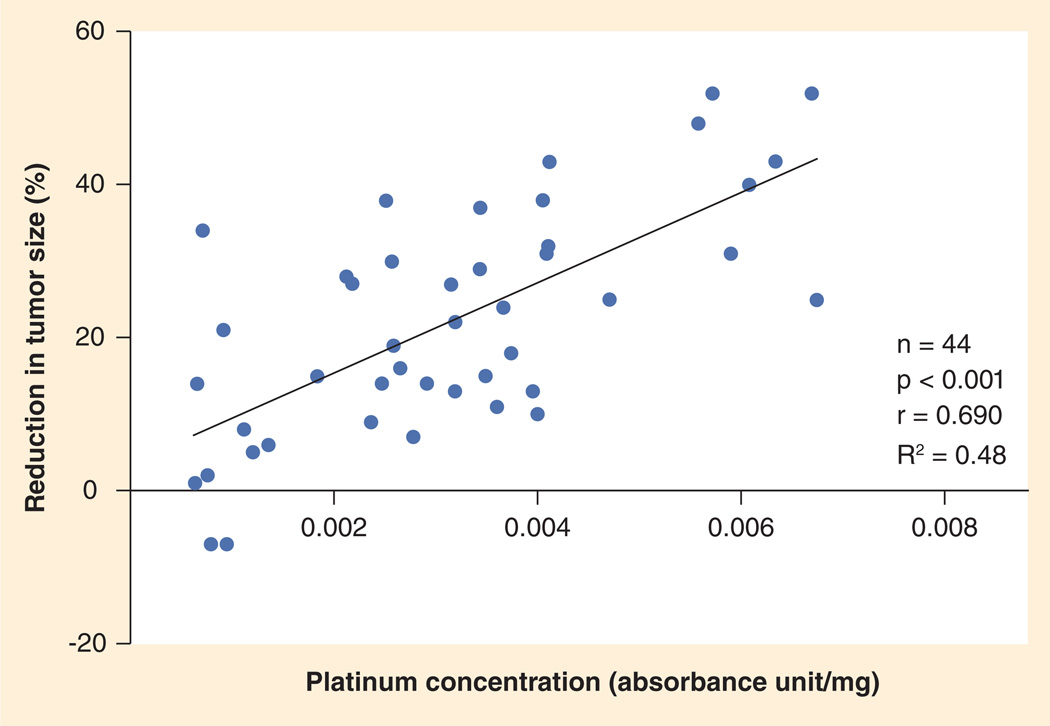

Accumulation of drug in tumor tissue is one possible measure of platinum-based drug efficacy. Kim et al. recently measured total platinum concentrations by flameless atomic absorption spectrophotometry in 44 archived fresh-frozen NSCLC specimens from patients who underwent surgical resection after neoadjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy [123]. Tissue platinum concentration was correlated significantly with percent reduction in tumor size on post-versus pre-chemotherapy computed tomography scans (Figure 2). The same correlations were seen with cisplatin, carboplatin and all histology subgroups. Furthermore, there was no significant impact of potential variables such as number of cycles and time lapse from last chemotherapy on platinum concentration. Patients with higher platinum concentration had longer time to recurrence, progression-free survival and overall survival. This clinical study established a relationship between tissue platinum concentration and response in NSCLC, suggesting that reduced platinum accumulation might be an important mechanism of platinum resistance in the clinical setting.

Figure 2. Pearson’s correlation between tissue platinum concentration and tumor response.

A highly significant correlation was observed between total tissue platinum concentration and percent reduction in tumor size.

Reproduced with permission from [123].

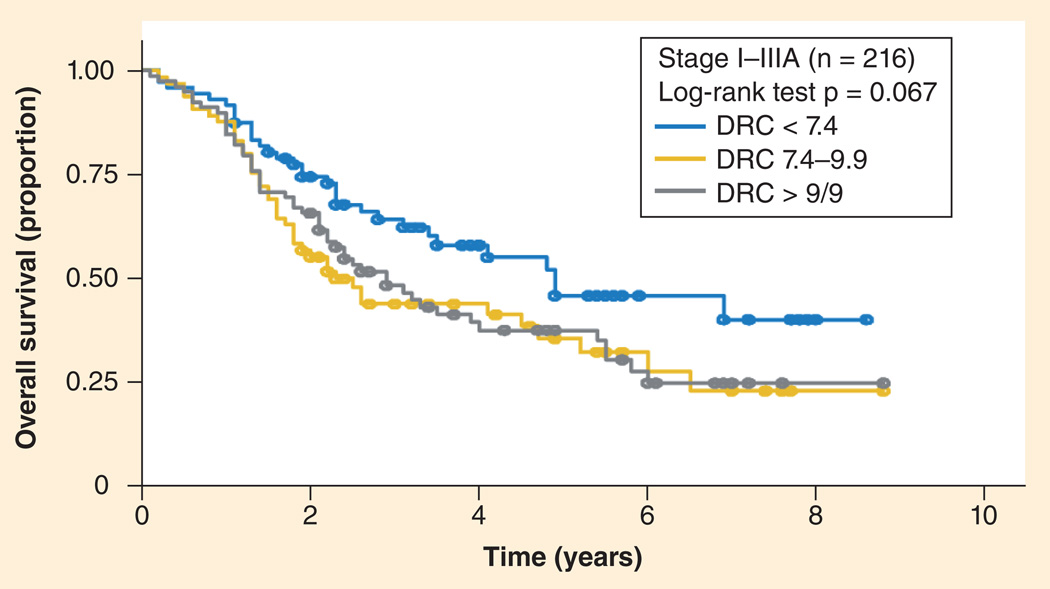

In a large clinical study, Wang et al. measured DNA repair capacity in cultured peripheral T-lymphocytes from 591 NSLC patients that were treated with platinum-based chemotherapy [124]. They found an overall inverse correlation between DNA repair capacity and survival, especially in early-stage tumors (Figure 3). Although they measured cellular capacity for repair of a carcinogen–DNA adduct in a plasmid, not repair of platinum–DNA adducts, the assay was specific for cellular NER capacity since the substrate was a bulky adduct. Importantly, this study was performed with sufficient patient numbers to conclude that surrogate tissues are likely to be useful for predictive biomarker applications. Although malignancies may possess numerous mutations compared with host normal tissues, cancers do initially inherit their genome from the host, which appears increasing likely to influence tumor sensitivity to therapy.

Figure 3. Overall survival curves correlated significantly to DNA repair capacity phenotype in selected patient groups.

p-values were obtained from the log-rank test. Non-small-cell lung cancer patients with stages I to IIIA.

DRC: DNA repair capacity.

Reproduced with permission from [124].

Oxaliplatin is a third-generation diaminocyclohexane–platinum complex that was developed to overcome resistance against cisplatin and carboplatin (Figure 1A). Oxaliplatin is part of the therapeutic standard regimens for the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer in combination with fluorouracil/leucovorin [125]. Oxaliplatin has also been used as a single agent in this disease and other malignancies. Besides treatment of patients with metastatic disease, oxaliplatin is also approved for adjuvant protocols [126]. Similar to other platinum coordination complexes, the cytotoxic activity of oxaliplatin is based upon the formation of mono- or bi-functional adducts with DNA [127].

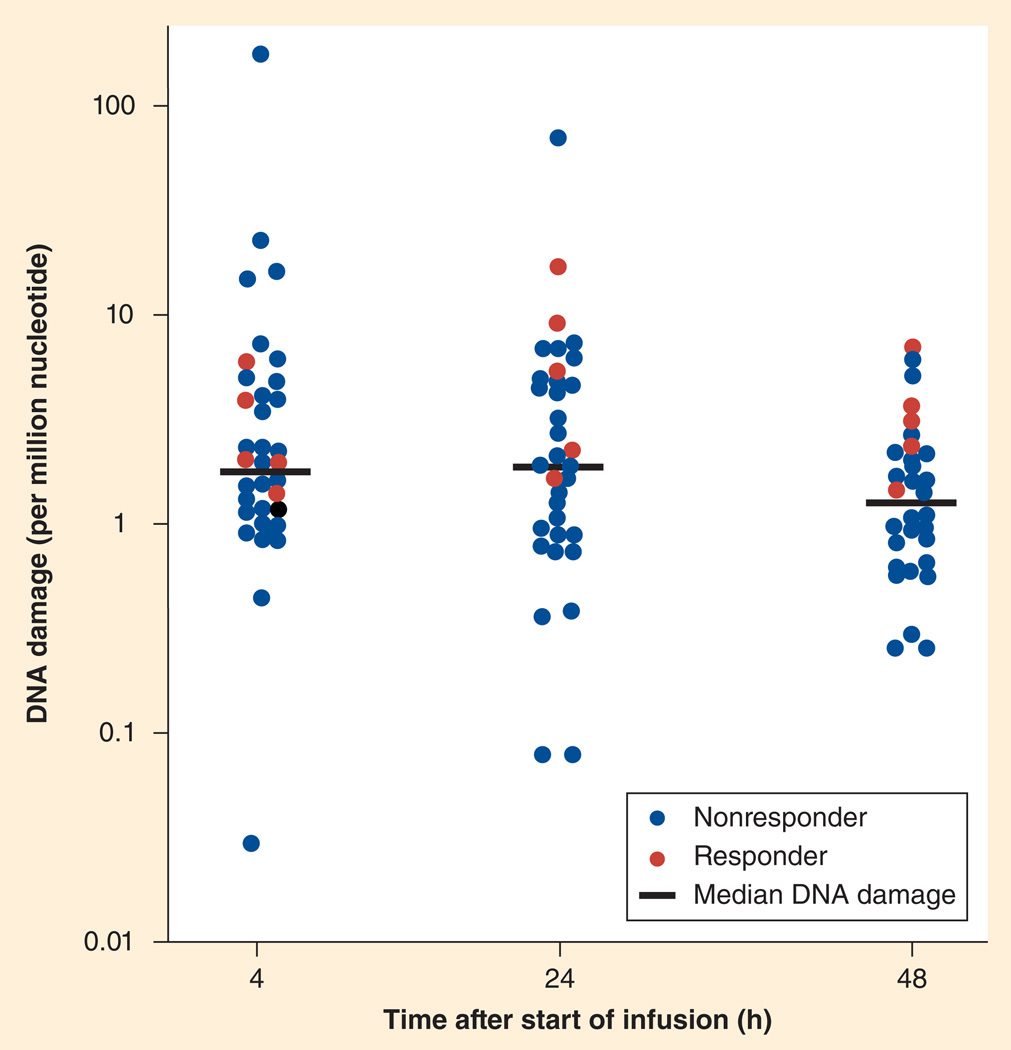

For oxaliplatin, only four reports were published on adduct levels in patients [128–131]. One study investigating a large number of patients and a potential relationship to tumor response and toxicity was reported by Pieck et al., who measured peripheral blood lymphocyte oxaliplatin–DNA adducts in 37 patients with a variety of malignancies [130]. In this study, oxaliplatin–DNA adducts were measured using absorptive stripping voltammetry using a modification of the method by Kloft et al. [132] and Weber et al. [133]. In patients showing tumor response, adduct levels after 24 and 48 h were significantly higher than in nonresponders (Figure 4), indicating that drug–DNA adduct levels may serve as biomarkers of response in surrogate tissues without the need to measure DNA repair capacity.

Figure 4. Individual and median platinum–nucleotide ratios (n = 37) of nonresponders and responders indicate that oxaliplatin–DNA adducts in peripheral blood monomuclear cells are useful as biomarkers of response and survival.

Reproduced with permission from [130].

The literature is currently lacking in reports defining the relationship between drug–DNA adducts levels achieved in PBMC and those achieved in solid tumors, especially with respect to therapeutic response. Two recent studies reported comparisons of drug–DNA adducts in biopsies of solid tumor and PBMCs during cisplatin-based chemotherapy [115,134]. Drug–DNA adduct levels were found to be two- to five-times higher in tumor biopsies compared with PBMC, but no correlation was observed between drug–DNA adduct levels in the two tissue types. These findings call into question the relevance of drug–DNA adduct levels in PBMCs as potential biomarkers for patient response to platinum-based chemotherapy.

However, no study has reported the correlation between drug–DNA adducts levels in tumors and patient outcomes. Furthermore, many of the mechanisms that determine access of platinum-based drugs to their molecular target(s) in patients are very poorly understood, as is the cellular response to the presence of the adducts in the clinical setting. Direct investigations of drug–DNA adduct formation in tumors should provide important insights into clinically relevant processes provided the technology for making such measurements is compatible with patient-oriented research. Aside from the obvious difficulty in obtaining tumor biopsy samples, the measurement technologies employed for platinum–DNA adduct identification and quantification have often been used near the LOD or LOQ. Recently, the technologies for measuring such low analyte levels have improved to the point where large enough studies to determine the usefulness of platinum–DNA adducts as biomarkers is becoming feasible.

Methods for measuring platinum drug–DNA adducts from clinical samples are improving

Below is a summary of the major technologies for measuring platinum–DNA adducts and their clinical applications. Each technology is briefly described along with available information regarding sensitivity, including LOD and LOQ, and a discussion of strengths and weaknesses regarding clinical utility. The salient results are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Overview of platinum–DNA adduct assays: applications and detection limits.

| Summary of assay | Reported sensitivity (including LOD and LOQ where specified, for adducts or platinum where appropriate) |

Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Polyclonal immunoassay | ||

| Rabbit antiserum against calf thymus DNA modified with cisplatin. Assay used to determine cisplatin–DNA adducts from testicular and ovarian cancer patients | 0.2–0.3 fmol/µg of DNA, approximately one adduct per 107 nt using 50 µg of DNA | [110,135,137–141] |

| Immunized rabbits with isolated platinum–GG or platinum–GA dinucleotides. Developed adduct specific ELISA assay requiring multiple enzymatic digestion steps followed by HPLC fractionation prior to assay. Used in PBMC clinical studies, testicular, bladder cancer cell lines, immunocytoma and rat spermatozoa cells | 0.02 fmol/µg of DNA, requiring >50 µg of DNA | [105,108,142–144] |

| Used to measure cisplatin–DNA adducts in tissue sections and cells isolated from animals and cancer patients | LOD of 2 × 104 per 1010 nt | [145–149,161–164] |

| Polyclonal antibody raised against DNA highly modified by cisplatin, allowed the detection of adducts at the single cell level in normal and tumor tissues | Approximately one adduct per 107 nt | [150] |

| Monoclonal immunoassay | ||

| ELISA method used to quantify adducts formed in patient tissues during therapy | LOQ of 3 fmol/µg of DNA, approximately one adduct per 106 nt | [120,121,151,152] |

| Immunocytological assay specific for platinum–GG and platinum–AG adducts that enabled quantification in cell nuclei | LOD was reported at 25,000 platinum–GG adducts per nucleus, or approximately four adducts per 106 nt | [114,153] |

| 32P post-labeling | ||

| Method involves digestion to nucleotides of DNA containing cisplatin- or carboplatin-induced adducts, followed by chromatographic separation of adducted nucleotides, deplatination, enzymatic labeling with [γ-32P]-ATP and thin-layer chromatography with quantification by autoradiography | LOD = 0.3 fmol per µg of DNA, approximately one adduct per 107 nt from 10 µg of DNA | [156] |

| Added an internal standard and improved adduct isolation and recovery. Demonstrated method on cultured cells and patient tissues | 1.6 adducts per 107 nt using 10 µg of DNA | [157] |

| Introduced online HPLC fractionation of adducts and optimized further the method reported in. Method was applied to normal and tumor tissues | LOQ for platinum–GG and platinum–AG adducts of 0.087 and 0.53 fmol per µg of DNA, respectively | [134,147,158] |

| LC–MS | ||

| LC–ESI-MS2 method to quantify cisplatin–DNA adducts after enzymatic digestion | LOD = 2 pmol | [161] |

| LC–ESI-MS2 of platinum-modified dinucleotides | LOD = 100 fmol for the platinum–GG adduct | [162] |

| LC–ESI-MS2 method for measuring oxaliplatin-induced intrastrand DNA crosslinks | LOD = 23 and 19 adducts per 108 nt for platinum–GG and platinum–AG adducts, respectively | [163] |

| Absolute quantitation of platinum–GG adducts formed from cisplatin exposure using a stable-isotope-labeled internal standard on an UPLC–MS/MS. Demonstrated on DNA isolated from cell lines and mouse tissues | LOQ = 3 fmol per µg of DNA, approximately 3.7 adducts per 108 nt | [164] |

| ICP-MS | ||

| Measured total adducts in patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. 24% of patient samples could not be measured | 10 pg of elemental platinum | [119] |

| Developed an improved method for preparing DNA for platinum analysis from cell lines treated with cisplatin or oxaliplatin. | LOD = 0.2 pg of platinum per µg of DNA, using 10 µg of DNA per assay | [167] |

| Determined platinum in DNA isolated from PBMC and gastric tissues from patients treated with cisplatin. | LOQ = 7.5 fg of platinum per µg of DNA or 0.038 fmol adduct per µg of DNA | [104] |

| Separated cisplatin–DNA adducts by HPLC prior to ‘offline’ determination of platinum content in each collected fraction | [170] | |

| Separated cisplatin–DNA adducts by HPLC with ‘online’ coupling to ICP-MS using Drosophila melangster larvae and cancer cell lines | [171–173] | |

| Stripping cyclic voltammetry | ||

| 37 patients with various solid tumors received oxaliplatin as a 2-h infusion. Oxaliplatin–DNA adduct levels were measured in the first treatment cycle using adsorptive stripping voltammetry. In patients showing tumor response, adduct levels after 24 and 48 h were significantly higher than in nonresponders | LOQ of 0.4 pg of platinum per ml or five adducts per 108 nt from 25 µg of DNA | [130] |

| Accelerator MS | ||

| Exposed purified DNA and cancer cell cultures to radiocarbon-labeled carboplatin and oxaliplatin. Later expanded to include additional cancer cell lines and an ongoing clinical study of bladder and lung cancer patients [176,185,186] | LOQ = 0.1–1 attomole for 14C or approximately one adduct per 1010 nt from 10 µg of DNA | [174,175,176,185,186] |

ICP: Inductively coupled plasma; nt: Nucleotide; PBMC: Peripheral blood mononuclear cell.

Immunoassay

Quantification of cisplatin–DNA adducts by immunoassay was first described by Poirier et al. in 1982 [135], who developed polyclonal anti-serum that had specificity primarily for the intrastrand bidentate adducts (platinum–GG and platinum–GA) derived from crosslinks in duplex DNA [136]. The immunoassay was used to determine cisplatin–DNA adducts in white blood cells from testicular and ovarian cancer patients undergoing cisplatin therapy [110,137–141]. Fichtinger-Schepman et al. developed antibodies against dinucleotides containing platinum–GG or platinum–GA adducts, which were used in a competitive ELISA after nuclease digestion of isolated DNA, followed by chromatographic separation of platinated dinucleotides [105,108,142]. The method was applied to in vivo and in vitro studies of cisplatin treatment, for example, peripheral leukocytes from patients receiving cancer chemotherapy, testicular and bladder tumor cell lines, immunocytoma cells and rat spermatozoa [143,144]. However, the laborious method required large amounts of DNA. Terheggen et al., developed a peroxidase-based immunoassay assay that was relatively insensitive, with an LOD of two adducts per 106 nucleotides, but compatible with quantitative determination of cisplatin–DNA adducts in tissue sections or cells from animals and cancer patients [145–149]. Meijer et al. developed an immunohistochemistry assay that allowed the detection of cisplatin–DNA adducts at a single-cell level in buccal and tumor cells of patients [150]. Tilby et al. [151] developed an ELISA method based upon a monoclonal antibody that was used to quantify carboplatin–DNA and cisplatin–DNA adducts formed in patients during therapy [120,121,152]. More recently, Leidert et al. reported monoclonal antibodies with defined specificities for the two major cisplatin–DNA adducts (platinum–GG and platinum–AG), which enabled quantification of cisplatin-induced lesions in individual cell nuclei [153].

Immunoassays are useful tools for the analysis of DNA adducts with sufficient sensitivity and selectivity for quantification of clinically relevant levels of platinum–DNA modifications. However, in practice, rather large amounts of DNA are needed, several specific antisera (one for each type of adduct) are required and cross-reactivity and nonlinear analytical responses are problematic. Immunoassays are not compatible with microdosing diagnostics, since the LODs are typically one to two orders of magnitude too high for detecting such small drug–DNA adducts levels without an unrealistic amount of DNA.

32P post-labeling

The use of 32P post-labeling for the detection of DNA adducts and other forms of DNA modification was introduced in the early 1980s [154,155]. Blommaert and Saris developed the strategy for the determination of intra-strand platinum–GG and platinum–AG adducts [156]. The method involves digestion of DNA followed by isolation of the positively charged platinum adducts using cation-exchange chromatography. Subsequently, the adducts were deplatinated (platinated dinucleotides are very poor enzymatic labeling substrates) and labeled with [γ-32P]-ATP. The resulting mixture was separated by a combination of thin-layer chromatography with autoradiography detection and HPLC with an online radioisotope detector. Although quite sensitive, the overall recovery was only 30%, and reproducible and accurate quantitative analysis was impossible due to the absence of an internal standard.

Welters et al. [157] and Pluim et al. [158] improved the method substantially by the inclusion of an internal dinucleotide standard, improved deplatination procedures and used a more efficient chromatography. The method was recently applied to normal tissue (white blood cells and buccal cells) and tumor tissue of patients undergoing platinum-based chemotherapy [134].

Despite the high sensitivity of 32P post-labeling, it suffers from several drawbacks, including the need for radioactivity with a rapid decay half-life, the use of reference standards and the inability to characterize unknown adducts that are potential confounders of the platinum–DNA adduct measurement. In addition, the entire 32P post-labeling procedure is labor intensive, requiring many manual and enzymatic steps that may be difficult to implement outside of the clinical study setting with high-throughput and acceptable QC.

MS

Until recently, the role of MS in the determination of DNA adducts has been limited to providing information for the identification of new DNA adducts, or for the structural characterization of DNA-adduct standards without emphasis on sensitive and precise quantitation. However, the recent development of LC coupled to MS and the ongoing technological advances in ionization methods, in particular ESI, have made the use of MS a viable method for the quantification of DNA modifications as well [159,160].

There are some reports of LC–MS methods for measurement cisplatin–DNA adducts. Da Col et al. applied LC–ESI-MS2 to analyze the complexes formed between nucleosides and cisplatin obtained by in vitro reaction of DNA samples with the drug [161]. Iijima et al. also used LC–ESI–MS2 to determine the main cisplatin adducts (platinum–GG and platinum–GA) in cells treated with the drug [162]. The adducts were enzymatically isolated from the DNA in the form of modified dinucleoside monophosphates and then separated from unmodified nucleosides by HPLC. Le Pla et al. reported the development of a LC–ESI-MS2 method for measuring GG and AG intrastrand crosslinks formed by oxaliplatin in wild-type and glutathione transferase P null mice treated with oxaliplatin [163]. Enzymatic digestion of DNA samples followed by SPE was used for sample preparation.

All the above reported MS methods lacked an internal standard, an essential tool for accurate and reproducible quantifications. Recently, Baskerville-Abraham et al. first reported the absolute quantification of cisplatin–DNA adducts by LC–MS using a stable-isotope-labeled internal standard and with a sensitivity approaching that of 32P post-labeling [164]. The method was applied to studies in ovarian carcinoma cell lines and C57/BL6 mice. However, this method is unsuitable for measurement of all described cisplatin–DNA adducts without additional development.

In general, molecular MS approaches provide high sensitivity and structural information of the adducts being quantified, but matrix effects, such as salts and other molecules, can interfere with adduct quantification [162]. Samples typically require extensive sample work-up, including both enzymatic and solid-phase or chromatographic speciation along with well-characterized isotopically labeled molecular standards for determination of sample recovery, molecular identification and quantification. As such, MS is currently increasingly useful for clinical studies, but it not yet viable as a platform for clinical diagnostics, such as microdosing, since LOQs of greater that one adduct per 108 nucleotides are likely required.

Inductively coupled plasma (ICP)-MS is a type of atomic MS that reports the amount of the selected element introduced into a plasma-ionization source [165,166]. Some advantages of ICP-MS include, high sensitivity, direct isotopic information and versatility in coupling with separation techniques (e.g., HPLC), but obtaining molecular information is a challenge. ICP-MS methods have high throughput with less tedious procedures owing to the ability to chemically digest the samples without concern for maintaining the structural integrity of the adducts prior to ionization. Bonetti et al. showed that ICP-MS allows determination of DNA platination at very low levels in leukocytes from patients receiving cisplatin- or carboplatin-based chemotherapy [119]. Yamada et al. developed an improved procedure of preparing ml-volume DNA samples before platinum determination by ICP-MS [167]. Brouwers et al. reported a highly sensitive ICP-MS method for the determination of platinum in DNA isolated from PBMCs and gastric-tissue samples from patients treated with cisplatin [168]. The method exhibits a LLOQ than that reported for the 32P-method (0.087 and 0.053 fmol adduct/µg DNA for platinum–GG and platinum–AG, respectively). Importantly, this paper reported measurements above the LOQ on less than 5 µg of DNA, which can be obtained from approximately 1 mg of tissue. Jarvis et al. reported comparisons of platinum–DNA adduct levels in normal mouse tissue, human tumor xenograft and human blood and tumor biopsy samples using atomic absorption spectroscopy and ICP-MS [169]. The ICP-MS samples were spiked with thallium to act as an internal reference to enable monitoring of instrument performance and to correct for variations in matrix effects and other potentially confounding technical issues. Morrison et al. reported separation of cisplatin–DNA adducts by anion-exchange HPLC before ‘offline’ ICP-MS detection of platinum in the resulting chromatographic fractions [170]. Garcia Sar et al. developed methodologies for precise, accurate quantification of cisplatin–DNA adducts based on ICP-MS detection with ‘online’ coupling to HPLC [171–173]. DNA samples were enzymatically digested before HPLC–ICP-MS analysis. The method was applied to cultures of brain and neck squamous carcinoma cell lines.

Overall, ICP-MS is a very sensitive technique for measuring platinum–DNA adducts that may be amenable to clinical studies. The ability to routinely measure adducts in the 1 per 108 nucleotide range from a few µg of DNA is compelling, even if structural characterization is absent from the measurements.

Stripping cyclic voltammetry of oxaliplatin–DNA adducts

Another sensitive analytical method for platinum is based on adsorptive stripping voltammetry. This ‘formazone method’ makes use of the catalytic hydrogen wave, which is due to the adsorption of a platinum–formazone complex at the hanging mercury drop electrode [133]. This highly sensitive method allowed the determination of platinum with a LLOQ of 0.4 pg ml or five adducts per 108 nucleotide from 25 µg of DNA. Pieck et al. used this method in a clinical study of patients with a variety of cancers dosed with oxaliplatin [130].

AMS

Briefly, AMS works by breaking down the molecules in a sample into atoms that are then identified and quantified in a small particle accelerator. If the sample is labeled with a rare isotope such as 14C, the concentration of radiocarbon atoms in the particle beam can be used to calculate the concentration of drug in blood, tissue, cells and subcellular components such as protein and DNA. AMS analysis typically requires the conversion of samples to graphite prior to analysis, which can be done using a high-throughput parallel process. A single laboratory technician can produce up to 300 samples per day. A single AMS instrument can run up to 20,000 samples per year, which is reasonable throughput for clinical diagnostics applications, considering there are approximately 300,000 patients per year that receive platinum-based therapy in the USA.

We first reported the measurement of [14C] carboplatin–DNA adducts from T24 bladder cancer cells treated with small doses of [14C] carboplatin, with a LOD of 1 amol per µg of DNA for carboplatin–DNA monoadducts [174]. Cells were treated with 1-µm (microdose) and 100-µm (therapeutic dose) carboplatin including 0.3 µm of [14C] carboplatin at a final concentration of 50,000 dpm/ml for 4 h, followed by washing and incubation in culture medium free of carboplatin. This procedure mimicked the in vivo intravenous dosing of carboplatin in which a bolus injection is followed by a rapid decrease in concentration after a few hours. The number of carboplatin–DNA monoadducts was calculated based on the 14C content in genomic DNA as measured by AMS. This work was followed up by a similarly designed oxaliplatin study in T24 and bladder cancer cells and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells, in which an LOD of 0.1 amol per mg of DNA was reported for total oxaliplatin–DNA adducts (monoadducts and crosslinks), with the increase in sensitivity presumably due to the greater chemical stability of the radiocarbon-containing adduct structures derived from oxaliplatin as compared with the carboplatin. We also demonstrated that the oxaliplatin–DNA adducts could be separately quantitated after enzymatic digestion to nucleosides and nucleotides followed HPLC fractional and ‘offline’ quantitation of radiocarbon by AMS [175]. We then tested the feasibility of using microdose-based diagnostics for the combination of carboplatin and gemcitabine in three bladder cancer cell lines that were exposed to microdoses and pharmacologically relevant ‘therapeutic’ doses of [14C] carboplatin plus and minus a range of gemcitabine concentrations followed by quantitation of carboplatin–DNA monoadduct levels by AMS [176]. We observed that the monoadduct levels were linearly proportional between the microdose and the therapeutic concentrations of carboplatin and gemcitabine had no influence on carboplatin–DNA monoadduct levels regardless of either drug’s concentration. These data supported the potential use of AMS for clinical studies on patients receiving cisplatin or carboplatin and gemcitabine – a common regimen. We then performed a systematic analysis in a set of six cancer cell lines that:

-

▪

Reproduced the observation of linearly proportional relationship between monoadduct levels and carboplatin dose;

-

▪

Showed that the cellular sensitivity (cytotoxicity) of the cells to carboplatin was proportional to monoadducts levels;

-

▪

That NER functioned on monoadducts, but that it was not the only factor responsible for accumulation of monoadducts over time (Figure 5).

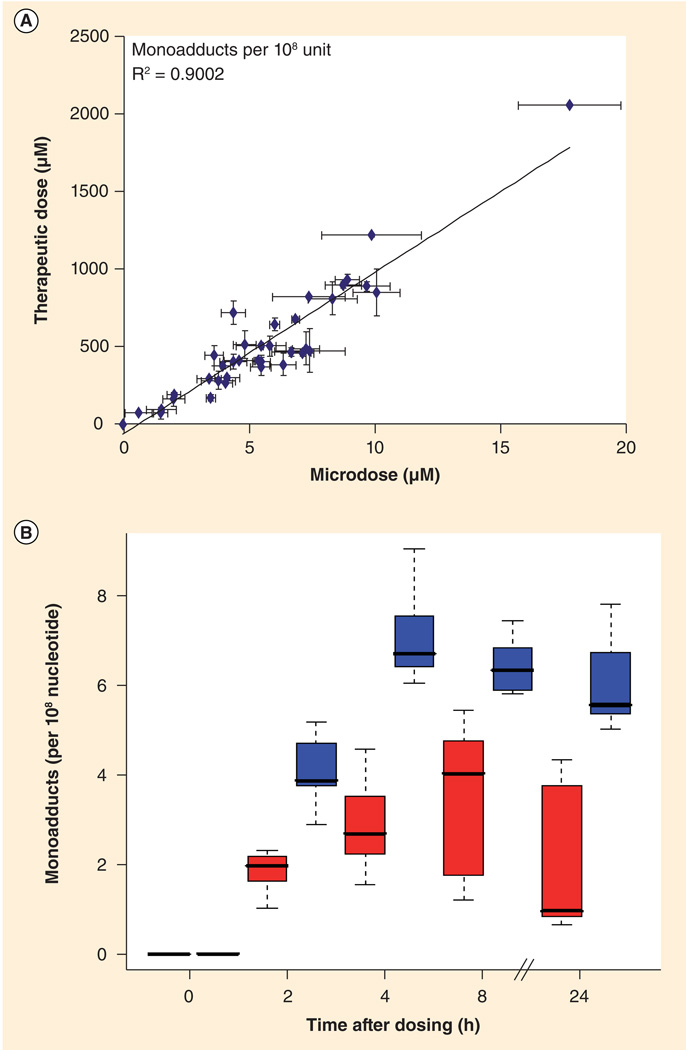

Figure 5. Microdose-induced carboplatin–DNA monoadduct levels correlate to therapeutic adduct levels and chemoresistance.

(A) Linear regression of carboplatin–DNA monoadduct levels induced by microdosing and therapeutic carboplatin. Cells were dosed for 4 h followed by washing and incubation in carboplatin-free medium. A linear relationship was observed (R2 = 0.9002, p < 0.0001) for DNA monoadduct levels between microdoses and therapeutic doses in all cell lines and at all time points. (B) Box plot comparing monoadduct levels in carboplatin-sensitive and -resistant cell lines over 24 h. Resistant cell lines (IC50 > 100 µm, red) had lower levels of platinum–DNA adducts than sensitive cell lines (IC50 < 100 µm, blue). Shows means of n = 3 for each data point (bars), standard deviation (boxes) and range (dashed lines) between sensitive and resistant cell lines.

Reproduced with permission from [185].

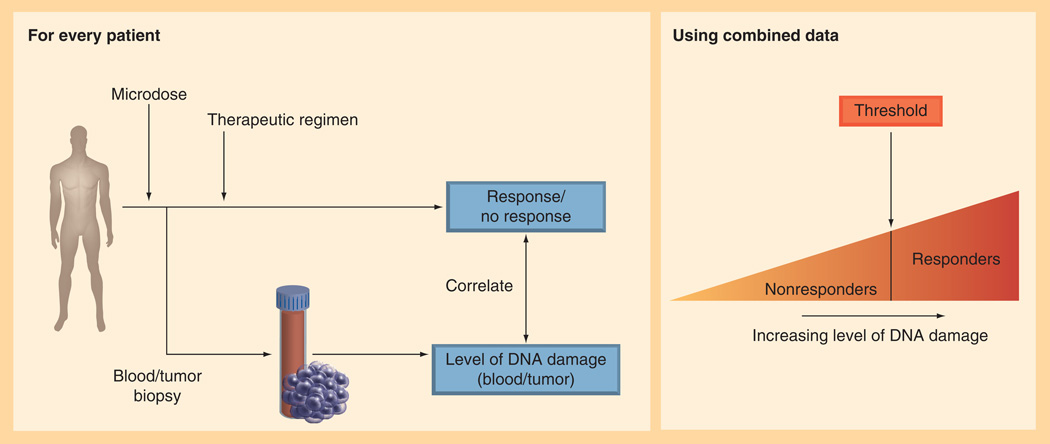

These and other unpublished data supported the initiation of an ongoing clinical study aimed at determining the cut-off point at which carboplatin–DNA monoadduct levels correlate with response to platinum-based chemotherapy in both PBMC and tumor tissue samples (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Carboplatin microdosing clinical trial protocol and goal of defining the threshold carboplatin–DNA monoadduct threshold that differentiates responders and nonresponders.

This evolving clinical test, called PlatinDx, is anticipated to provide direct measurement of in vivo tumor responses to a microdose (~1/100th the therapeutic dose) of carboplatin. Although the microdose has no treatment efficacy, it safely allows measurement of tumor responses such as drug uptake, drug efflux and drug–DNA damage that are predictive of whether the therapeutic dose will kill the tumor cells. PlatinDx uses commercially available GMP quality [14C] carboplatin at such low doses as to minimize chemical and radioactive exposure to acceptable limits for human use. A nontoxic microdose provides approximately 0.5% of a chest CT scan of radiation exposure per patient. Since carboplatin and cisplatin effectively form the same platinum–DNA adducts in vivo because of the identical cis-diamine carrier ligands (Figure 1), cells exposed to both agents have overlap in their chemoresistance spectra. Therefore, a carboplatin-based assay may be predictive for cisplatin therapy as well (cisplatin is not available with a 14C label since it contains no carbon atoms).

The ongoing 85-patient clinical study [202] will determine rigorously the correlation of AMS data from microdoses of [14C] carboplatin to patient outcomes such as tumor shrinkage and survival after chemotherapy, in order to define the cut-off point for predicting responders and nonresponders using the PlatinDx test (Figure 5A & B). This will be accomplished by formal validation of the carboplatin–DNA damage assay and conduct of a clinical study with lung and bladder cancer patients designed to provide sufficient statistical power to identify the cutoff value in the carboplatin–DNA monoadducts level for the stratification of patients according to response to platinum-based chemotherapy.

Future prospects for microdosing with platinum-based drugs

PARP inhibitors in combination with platinum-based therapy

PARP is one of the most abundant nuclear proteins in eukaryotes. The cellular functions of PARP-1 include modulation of chromatin structure and transcription, as well as DNA repair housekeeping. When genomic DNA is mildly damaged, PARP-1 is fully activated to recruit repair machinery and signal downstream effectors [177,178]. PARP-1 mainly detects single-strand breaks, obligatory intermediates in BER and NER. PARP-1 thus participates actively in BER, and there is accumulating evidence for a role in NER [179]. The affinity of PARP-1 for cisplatin-damaged DNA has been established by photo-crosslinking studies, and in vitro binding assays further revealed the binding of PARP-1 to DNA damaged by cisplatin, oxaliplatin and pyriplatin, a recently developed potential therapeutic compound [180–182]. In the case of BRCA1 mutant cancer cells, they often have loss of function in the DNA repair of double-strand breaks, resulting in sensitivity to PARP inhibitors.

Recent evidence has demonstrated that faulty recombination repair due to BRCA mutations improves clinical response in some patients to platinum-based chemotherapy in combination with PARP inhibitors such as Abbott’s ABT-888. Hundreds of genes must be involved in a very complex cellular response to this therapy. Rather than performing involved genetic and RT-PCR analysis, our approach will be to measure phenotypic properties of a set of rationally chosen cell lines and tumors in order to better understand the influence of PARP inhibition on carboplatin-induced drug–DNA damage. Measurement of the influence of PARP inhibition on the carboplatin–DNA monoadduct levels (the precursor of all platinum–DNA crosslinks) may be useful in validating the therapeutic strategy and for informing clinical trial design. The resulting data may provide a collective measure of the influence of the complex network of genes related not only to DNA repair, but also to drug metabolism (e.g., influx, efflux and intracellular inactivation). This data may inform very practical decisions such as whether a PARP inhibitor should be given concurrently with chemotherapy or timed to allow maximum drug–DNA damage. Diagnostic microdosing can be applied to the study of other chemotherapy doublets partners, such as doxorubicin. Another advantage to this strategy is the potential to stratify patient populations into responders and nonresponders as part of the clinical program and possibly for the development of companion diagnostics.

Copper transport

Uptake of cisplatin is mediated by the copper transporter CTR1 in cultured cells. Ishida et al. showed in human ovarian tumors that low levels of CTR1 mRNA are associated with poor clinical response to platinum-based therapy [183]. In addition, using a mouse model of human cervical cancer, they demonstrated that combined treatment with a copper chelator, called tetrathiomolybdate, and cisplatin increased cisplatin–DNA adduct levels in cancerous but not in normal tissues, thus impairing angiogenesis with improved therapeutic efficacy. The copper chelator also enhanced the killing of cultured human cervical and ovarian cancer cells with cisplatin. This mechanism of resistance is thought to be similar for cisplatin and carboplatin, which share the same putative transporter CTR1 [184]. These efforts identified the copper transporter as a potential therapeutic target, which can be manipulated with copper chelating drugs to selectively enhance the benefits of platinum-containing chemotherapeutic agents. The use of carboplatin-based microdosing may enable selection of patients whose tumors have enhanced response to platinum-based chemotherapy as a result of copper chelation.

Future perspective

Personalized medicine is poised to have a profound effect on the individualized treatment of cancer patients. The heterogeneous nature of cancer tumors and their propensity to undergo selection for resistant mutants and clonal expansion after therapy demands genotypic and phenotypic analysis in order to maximize treatment efficacy. Genomic analysis is predominating targeted therapy owing to the impact of mutational signatures on the development of resistance to this class of agents. Response to cytotoxic agents is multifactorial, and no specific mutational signatures of resistance predominate in the clinic. For platinum-based chemotherapy, the ability to sensitively detect platinum–DNA adducts is likely to lead to phenotypic assays that predict response to therapy. Although LC–MS and ICP-MS have more recently emerged as promising technologies for correlating response to therapy to platinum–DNA adduct levels, only AMS has so far demonstrated sufficient sensitivity and precision for the quantitation of the adducts after exposure to subtherapeutic doses for diagnostic purposes. We believe that future cancer treatments will likely be optimized by the combination of both genotypic and phenotypic assays.

Executive summary.

Background

-

▪

Cancer is a heterogeneous disease and multiple drugs are required for treatment regimes.

-

▪

Biomarkers are in development and can be prognostic or predictive.

Lung & bladder cancer treatment & associated biomarkers under investigation

-

▪

Treatment protocols typically include combinations including platinum drugs.

-

▪Key questions for clinicians include the choice of:

-

▪Neo-adjuvant or adjuvant therapy?

-

▪Drug or drug combination to be used on a particular patient?

-

▪What biomarkers should be measured before treatment?

-

▪Can a surrogate tissue be used or just the tumor tissue?

-

▪

Biomarkers

-

▪

Biomarkers studied for optimized treatment of lung and bladder cancer include genetic markers and platinum drug–DNA damage.

Methods for platinum drug–DNA adduct measurement

-

▪

Immunoassay, 32P post-labeling, LC–MS, inductively coupled MS, stripping cyclic voltammetry, accelerator MS (AMS) all can be used for platinum drug–DNA adduct measurement.

Uses of platinum drug AMS studies

-

▪

Other potential uses of platinum drug AMS studies include investigating the effect of PARP inhibitors in combination with platinum-based therapy, and the role of copper chelators to selectively enhance platinum drug uptake by tumors.

Acknowledgements

We are extremely thankful to K Turteltaub and M Malfatti of Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, R de Vere White, D Gandara and Primo Lara of UC Davis, and S Dueker of Vitalea Science, for help.

This work was supported by NIH/NCI SBIR Contracts HHSN261201000133C, HHSN261201 200048C, HHSN261201200084C and NIH/NCRR P41 RR13461. G Cimino and P Henderson are employees of Accelerated Medical Diagnostics. C Pan has an ownership stake in Accelerated Medical Diagnostics and is supported by a VA Career Development Award. P Henderson is an inventor on a relevant patent application pending before the USPTO that is owned by Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory.

Key Terms

- Genetic progression

Hallmark of a cancerous cell in which its genome displays genetic instability by the accumulation of multiple genomic alterations at an enhanced, often increasing rate compared with a normal cell.

- Tumor type

Historically, this term referred to the tissue/organ of origin of a cancer. Today, tumor type additionally refers to a collection of molecular characteristics of the tumor via protein or mRNA expression, or specific genetic alterations.

- Biomarker

Molecular characteristic of a patient, a patient’s tumor, or both, that provides genotypic or phenotypic information that is useful for treatment planning or assessing treatment efficacy.

- Targeted antitumor agents

New class of anticancer molecules being developed to interfere with signaling pathways within a cell that are associated with cell growth and division. These drugs slow the growth rate of cancer cells, but are not mechanistically designed to kill the tumors.

- Microdose-based diagnostics

Diagnostic assay that measures a PD effect of a drug, administered at a sub-therapeutic, nontoxic dose, as a predictor of therapeutic response to full-dose therapy.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own.

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed. No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

▪ of interest

▪▪ of considerable interest

- 1.Marusyk A, Almendro V, Polyak K. Intra-tumour heterogeneity: a looking glass for cancer? Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2012;12(5):323–334. doi: 10.1038/nrc3261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Cancer genes and the pathways they control. Nat. Med. 2004;10(8):789–799. doi: 10.1038/nm1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paul SM, Mytelka DS, Dunwiddie CT, et al. How to improve R&D productivity: the pharmaceutical industry’s grand challenge. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2010;9(3):203–214. doi: 10.1038/nrd3078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jiang J, Liang X, Zhou X, Huang R, Chu Z. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing carboplatin-based to cisplatin-based chemotherapy in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2007;57(3):348–358. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2007.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hotta K, Matsuo K, Ueoka H, Kiura K, Tabata M, Tanimoto M. Meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials comparing Cisplatin to Carboplatin in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004;22(19):3852–3859. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.02.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Santis M, Albers P, Bokemeyer C. First line chemotherapy for bladder cancer. Onkologe. 2012;18(11):1012–1017. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sordella R, Bell DW, Haber DA, Settleman J. Gefitinib-sensitizing EGFR mutations in lung cancer activate anti-apoptotic pathways. Science. 2004;305(5687):1163–1167. doi: 10.1126/science.1101637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dempke WC, Suto T, Reck M. Targeted therapies for non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2010;67(3):257–274. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2009.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hewish M, Lord CJ, Martin SA, Cunningham D, Ashworth A. Mismatch repair deficient colorectal cancer in the era of personalized treatment. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2010;7(4):197–208. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2010.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bast RC., Jr Molecular approaches to personalizing management of ovarian cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2011;22(Suppl. 8):viii5–viii15. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bohanes P, Labonte MJ, Lenz HJ. A review of excision repair cross-complementation group 1 in colorectal cancer. Clin. Colorectal Cancer. 2011;10(3):157–164. doi: 10.1016/j.clcc.2011.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kang H, Kauh JS. Chemotherapy in the treatment of metastatic gastric cancer: is there a global standard? Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2011;12(1):96–106. doi: 10.1007/s11864-010-0135-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sudhindra A, Ochoa R, Santos ES. Biomarkers, prediction, and prognosis in non-small-cell lung cancer: a platform for personalized treatment. Clin. Lung Cancer. 2011;12(6):360–368. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klastersky J, Awada A. Milestones in the use of chemotherapy for the management of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2012;81(1):49–57. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tanner NT, Pastis NJ, Sherman C, Simon GR, Lewin D, Silvestri GA. The role of molecular analyses in the era of personalized therapy for advanced NSCLC. Lung Cancer. 2012;76(2):131–137. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2011.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2012;62(1):10–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bepler G, Gautam A, McIntyre LM, et al. Prognostic significance of molecular genetic aberrations on chromosome segment 11p15.5 in non-small-cell lung cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2002;20(5):1353–1360. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.5.1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doddoli C, Barlesi F, Trousse D, et al. One hundred consecutive pneumonectomies after induction therapy for non-small cell lung cancer: an uncertain balance between risks and benefits. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2005;130(2):416–425. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alberts WM. Introduction: diagnosis and management of lung cancer: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2003;123(Suppl. 1):1S–337S. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sandler A, Gray R, Perry MC, et al. Paclitaxel-carboplatin alone or with bevacizumab for non-small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;355(24):2542–2550. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Delbaldo C, Michiels S, Rolland E, et al. Second or third additional chemotherapy drug for non-small cell lung cancer in patients with advanced disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2007;4 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004569.pub2. CD004569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]