Abstract

The field of aging and dementia is increasingly preoccupied with identification of the asymptomatic phenotype of Alzheimer disease (AD). A quick glance at historical landmarks in the field indicates that the agenda and priorities of the field have evolved over time. The initial focus of research was dementia. In the late 1980s and 1990s, dementia researchers reported that some elderly persons are neither demented nor cognitively normal. Experts coined various terms to describe the gray zone between normal cognitive aging and dementia, including mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Advances made in epidemiologic, neuroimaging, and biomarkers research emboldened the field to seriously pursue the avenue of identifying asymptomatic AD. Accurate “diagnosis” of the phenotype has also evolved over time. For example, the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) Task Force is contemplating to use the terms major and minor neurocognitive disorders. The six papers published in this edition of the journal pertain to MCI which is envisaged to become a subset of minor neurocognitive disorders. These six studies have three points in common: 1) All of them are observational studies; 2) They have generated useful hypotheses or made important observations without necessarily relying on expensive biomarkers; and 3) Based on the new National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Association guidelines, all the studies addressed the symptomatic phase of AD. Questionnaire-based observational studies will continue to be useful until such a time that validated biomarkers, be it chemical or neuroimaging, become widely available and reasonably affordable.

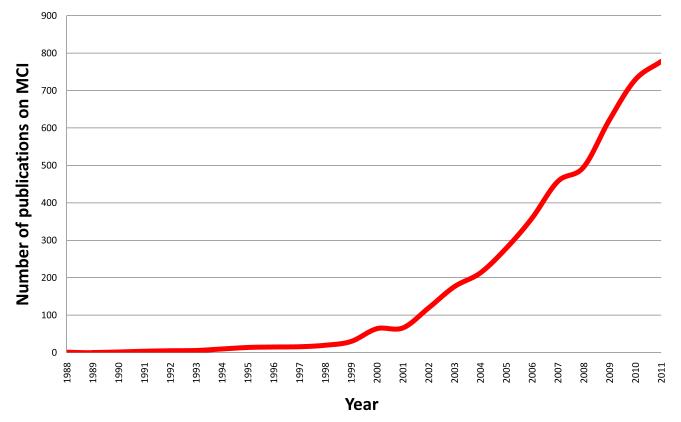

The field of aging and dementia is increasingly preoccupied with identification of the asymptomatic phenotype of Alzheimer disease (AD). This has become more apparent in the past few years.1 A quick glance at historical landmarks in the field of aging indicates that the agenda and priorities of the field have evolved over time. The initial focus of research was dementia. Determinations of key epidemiologic indices and identification of risk factors for dementia appeared to have created a ripe condition to investigate high risk groups for dementia. Indeed, in the late 1980s and 1990s, dementia researchers reported that some elderly persons are neither demented nor cognitively normal. Experts coined various terms2-7 to describe the gray zone between normal cognitive aging and dementia, including mild cognitive impairment (MCI).2 Investigators also suggested a theoretical construct that puts various levels of cognitive impairment on a spectrum spanning from normal cognitive aging on one pole and fullblown dementia on the other extreme. Thus, terms such as age-associated memory impairment,6 aging-associated cognitive decline,7 benign forgetfulness,5 etc. fall on the aging side of the spectrum whereas terms such as questionable dementia and malignant forgetfulness may fall on the dementia side of the spectrum. Terms such as MCI and minor neurocognitive disorder describe the intermediate stage between normal aging and dementia. The interest in MCI showed an exponential growth over the last decade (figure). For example, prior to 1999, there were less than 50 publications on the subject of MCI. By the year 2004, there were over 300 publications on MCI and the numbers kept increasing. Advances made in epidemiologic, neuroimaging, and biomarkers research emboldened the field to seriously pursue the avenue of identifying asymptomatic AD. Thus, the priority and emphasis of the field appears to have evolved from dementia to MCI, and more recently to identification of the asymptomatic phenotype of AD.

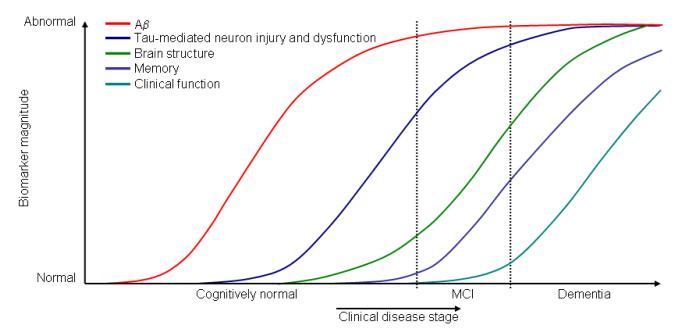

Accurate “diagnosis” of the phenotype has also evolved over time. For example, the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (DSM-IV) diagnostic criteria for dementia8 and the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS-ADRDA) criteria for AD9 are widely used in research and clinical settings. However, recent initiatives are underway to update these criteria in order to reflect the scientific advances made in the field. The two notable initiatives are the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) Task Force on Cognitive Disorders,10 and the National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Association (NIA-AA). The DSM-5 task forces were organized over the last few years and are methodically revising the criteria for various disorders including the envisaged neurocognitive disorders. The terms major neurocognitive disorder and minor neurocognitive disorder are both old and new. The term minor neurocognitive disorder is not new. In 1994, the American Psychiatric Association defined a research criterion for minor neurocognitive disorder that essentially describes the gray zone between normal cognitive aging and dementia. Additionally, minor neurocognitive disorder encompasses cognitive disorders that occur outside of aging and dementia as well.10 This implies that MCI will become a subset of minor neurocognitive disorder. In 2007, an expert panel on Human Immunodeficiency Virus coined the phrase HIV-Associated Neurocognitive Disorders (HAND) and “retired” the phrase AIDS dementia. Furthermore, HAND was divided into major neurocognitive disorders and minor neurocognitive disorders.11 The DSM-5 Task Force is contemplating a similar approach, i.e., to classify cognitive disorders into major neurocognitive disorder and minor neurocognitive disorder. While the DSM-5 Task Force had been deliberating methodically over the last few years, the NIA-AA Task Force rapidly developed and published its own classification scheme. The NIA-AA Task Force classified AD into three phases: 1) a preclinical phase (research category);12 2) MCI due to AD;13 and 3) dementia due to AD.14 The NIA-AA guidelines put a heavy emphasis on biomarkers. The enthusiasm about biomarker measures is also reflected in the hypothetical model developed to understand biomarker defined preclinical stages of AD (Figure).15 This theoretical model is anchored upon the amyloid hypothesis that posits that the accumulation of amyloid β-peptide in the brain is the primary driving force of neurodegeneration in AD; furthermore, other AD pathologies such as neurofibrillary tangles, neuronal injury, and atrophy are considered to be downstream events to amyloid β-peptide deposition in the brain.16 A recent landmark study further reinforced the amyloid hypothesis.17 The amyloid pathology may precede neuronal injury by as many as 20 years. Therefore, within the preclinical stages of AD, amyloid biomarkers such as CSF Aβ42 or positron emission tomography (PET) amyloid imaging are hypothesized to be useful and, as the disease progresses, biomarkers of neuronal injury such as CSF Tau, Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-PET, or atrophy on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain may be more informative. This hypothetical model is yet to be validated. Even if it is validated, is there any merit to studies that do not primarily rely on biomarkers and neuroimaging? The answer is a resounding yes, as demonstrated by six studies published in this edition of the American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry (AJGP). The six studies on MCI published in this edition of the journal have three points in common: 1) All of them are observational studies; 2) They have generated useful hypotheses or made important observations without necessarily relying on expensive biomarker or neuroimaging measures; and 3) Based on the new NIA-AA guidelines, all the studies addressed the symptomatic phase of AD. The six studies represent three continents. Three of the six publications are results of the Sydney Memory and Ageing Study; therefore, the methodological “blessings and curses” of the parent study apply to all three papers. The fourth study is from Europe, and the remaining two are from the United States. The study by Spanish investigators from “Fundación Jiménez Díaz” in Madrid, Spain, assembled a prognostic cohort of 210 subjects with amnestic MCI (aMCI) and followed them to the outcome of dementia or censoring variables.18 The exposure of interest was baseline recognition memory discrimination index (DI) as measured by the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test. The aMCI subjects with a baseline DI of <8 had a three-fold increased risk of developing dementia. The authors concluded that a recognition test may help to identify the subset of aMCI subjects that are at increased risk of developing incident dementia. The investigators used a well-validated neuropsychological test to measure outcome; this can serve as a useful and affordable prognostic test. However, this is not necessarily an innovative work. Additionally, this study is one more work that took the risk of using a “circular” argument to predict MCI outcomes. On the other hand, investigators from the Monongahela-Youghiogheny Healthy Aging Team19 avoided the trap of a “circular” argument. They defined MCI in terms of neuropsychometrics. They then used Instruments of Daily Living (IADL) as the “outcome” of interest in a cross-sectional study involving 1,737 community-dwelling adults aged 65 years and older. As expected, subjects with multi-domain MCI had higher odds of having problems with IADL. On a positive note, “better preserved” executive function was associated with lower odds of having a decline in IADL. The direction of causality is unknown in cross-sectional studies. However, cross-sectional studies are useful in generating hypotheses that need to be tested in prospective cohort studies.

Investigators from the Sydney Memory and Ageing Study20 examined the risk of falls in a cohort of 419 non-demented community-dwelling adults aged 70 to 90 years. Determining the incidence of falls can be tricky for the following reason. In a cohort study, the outcome of interest should not be present at baseline. Therefore, one has to exclude all subjects with a history of “fall”. This is a nearly impossible task since human beings are likely to experience falls at some point in their lives. Therefore, one has to come up with an arbitrary definition of fall. Indeed this is what the Australian investigators did. They defined fall as “at least one injurious fall or at least two noninjurious falls” during a 12-month follow-up period. Based on this definition, they observed that the incidence of falls is higher in MCI than in cognitively normal persons. A stratified analyses by MCI subtype indicated that the risk is higher for non-amnestic MCI; however, the wider confidence interval suggests that the analyses by MCI subtype lacked precision.21 Additionally, one is left with a lingering question as to why the investigators chose odds ratios to estimate risk in their “prospective cohort” study. Time is a key variable in a longitudinal study. Thus, one typically uses risk estimates such as hazard ratios that take time into account when measuring the association between exposure and outcome.22 This study at least generates a hypothesis that others can test in a larger prospective cohort followed over a period of several years. Another group of investigators from the Sydney Memory and Ageing Study measured the prevalence of MCI and risk factors of MCI in a cross-sectional study.23 The authors report a rather higher prevalence rate (39%) of MCI for a community-dwelling sample. This is in contrast with the 22% prevalence rate reported by the population-based Cardiovascular Health Study24 and the 16% prevalence rate reported by the population-based Mayo Clinic Study of Aging.25 The investigators did not observe differences in prevalence rates by sex. However, a recent large-scale population-based study had reported that the prevalence of MCI is higher in men than women,25 and more importantly, the same group confirmed this finding in a subsequent incidence study.26 As the authors pointed out, not all studies have shown sex differences in the frequency of MCI.27 The investigators have also explored cross-sectional associations with various potential risk factors, and they appropriately caution the reader that they are not reporting a cause-effect relationship. A third group of investigators from Australia conducted a study comparing the prevalence and incidence of MCI between participants with an English-speaking background and those with a non-English-speaking background. There was no difference in the incidence of MCI between the two groups; however, the prevalence of MCI was 2 to 3 times “higher” in the non-English-speaking background group. This study is an important reminder that psychometric tests, when applied to minority groups of different cultures, can potentially lead to spurious results. All three studies reported from the Sydney Memory and Ageing Study are limited by an 88% decline rate thus making the findings vulnerable to volunteer/refusal bias.28

The sixth publication on MCI in this edition of AJGP comes from the Alzheimer’s disease center of Boston University. The authors examined two variables by using a relatively smaller sample.29 They wanted to know if there is a difference in the estimation of risk by subjects with MCI (n = 39) in comparison with normal controls (n = 40). They also wanted to compare the risk estimation of study partners (n = 28) of MCI subjects with the study partners (n = 36) of normal controls. They report that risk estimation of MCI subjects and their study partners is different from normal controls and their study partners. The authors conclude that the risk difference results from the common perception of MCI patients and their partners regarding medications used for treatment of MCI. This is a relatively small study that generated useful information. One challenge while reading this article, is the need to make a conscious effort to continuously keep in mind as to which groups are being compared.

In summary, the six studies in this edition of the journal examined prognostic factors for MCI, and in the new NIA-AA parlance, the studies examined the symptomatic phase of AD. The findings are useful and they are generated by valid scales. If they were to use biomarkers, be it chemical or neuroimaging, then the studies would have relied on a more objective parameter as compared to questionnaires. However, the studies would have been prohibitively expensive given the large sample size of these studies. Additionally, biomarkers are not immune from bias either.30 The ideal future observational study would use affordable, widely available, and validated biomarkers to measure the progression from normal cognitive aging to MCI and subsequently to dementia.

Figure 1.

Number of publications directly relevant to mild cognitive impairment by year.

Figure 2. Dynamic biomarkers of the Alzheimer’s pathological cascade.

Aβ is identified by CSF Aβ42 or PET amyloid imaging. Tau-mediated neuronal injury and dysfunction is identified by CSF tau or fluorodeoxyglucose-PET. Brain structure is measured by use of structural MRI. Aβ=β-amyloid. MCI=mild cognitive impairment.

Footnotes

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Schneider LS. Organising the language of Alzheimer’s disease in light of biomarkers. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:1044–1045. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70246-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petersen RC, Smith GE, Waring SC, et al. Mild cognitive impairment: clinical characterization and outcome. Arch Neurol. 1999;56:303–308. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.3.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reisberg B, Ferris SH, de Leon MJ, et al. Global Deterioration Scale (GDS) Psychopharmacol Bull. 1988;24:661–663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flicker C, Ferris SH, Reisberg B. Mild cognitive impairment in the elderly: predictors of dementia. Neurology. 1991;41:1006–1009. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.7.1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kral VA. Senescent forgetfulness: benign and malignant. Can Med Assoc J. 1962;86:257–260. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crook T, Bartus RT, Ferris SH, et al. Age-associated memory impairment: proposed diagnostic criteria and measures of clinical change — report of a National Institute of Mental Health work group. Dev Neuropsychol. 1986;2:261–276. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levy R. Aging-associated cognitive decline. Working Party of the International Psychogeriatric Association in collaboration with the World Health Organization. Int Psychogeriatr. 1994;6:63–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Psychiatric Association . Task Force on DSM-IV: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV. 4th. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 1994. American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- 9.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, et al. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: Report of the NINCDS-ADRDA work group under the auspices of the Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ganguli M, Blacker D, Blazer DG, et al. Classification of neurocognitive disorders in DSM-5: a work in progress. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;19:205–210. doi: 10.1097/jgp.0b013e3182051ab4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Antinori A, Arendt G, Becker JT, et al. Updated research nosology for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Neurology. 2007;69:1789–1799. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000287431.88658.8b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, et al. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:280–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jack CR, Jr., Knopman DS, Jagust WJ, et al. Hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers of the Alzheimer’s pathological cascade. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:119–128. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70299-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science. 2002;297:353–356. doi: 10.1126/science.1072994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jonsson T, Atwal JK, Steinberg S, et al. A mutation in APP protects against Alzheimer/’s disease and age-related cognitive decline. Nature. 2012 doi: 10.1038/nature11283. advance online publication: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gomez-Tortosa E, Mahillo-Fernandez I, Guerrero R, et al. Outcome of mild cognitive impairment comparing early memory profiles. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011 doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31823038c6. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hughes TF, Chang CC, Bilt JV, et al. Mild cognitive deficits and everyday functioning among older adults in the community: The Monongahela-Youghiogheny Healthy Aging Team Study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012 doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3182423961. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Delbaere K, Kochan N, Close JCT, et al. Mild cognitive impairment as a predictor of falls in community-dwelling older people. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012 doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31824afbc4. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hulley SB. Designing Clinical Research. 3rd Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia, PA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Szklo M, Nieto FJ. Epidemiology: Beyond the Basics. 2nd Jones and Bartlett Publishers; Sudbury, Mass.: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sachdev PS, Lipnicki DM, Crawford J, et al. Risk profiles for mild cognitive impairment vary by age and sex: The Sydney Memory and Ageing Study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012 doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31825461b0. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lopez OL, Jagust WJ, DeKosky ST, et al. Prevalence and classification of mild cognitive impairment in the Cardiovascular Health Study Cognition Study: part 1. Arch Neurol. 2003;60:1385–1389. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.10.1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petersen RC, Roberts RO, Knopman DS, et al. Prevalence of mild cognitive impairment is higher in men. The Mayo Clinic Study of Aging. Neurology. 2010;75:889–897. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181f11d85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roberts RO, Geda YE, Knopman DS, et al. The incidence of MCI differs by subtype and is higher in men: the Mayo Clinic Study of Aging. Neurology. 2012;78:342–351. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182452862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Di Carlo A, Lamassa M, Baldereschi M, et al. CIND and MCI in the Italian elderly: frequency, vascular risk factors, progression to dementia. Neurology. 2007;68:1909–1916. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000263132.99055.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sackett DL. Bias in analytic research. J Chronic Dis. 1979;32:51–63. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(79)90012-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jefferson AL, Wong S, Bolen E, et al. Cognitive correlates of HVOT performance differ between individuals with mild cognitive impairment and normal controls. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 2006;21:405–412. doi: 10.1016/j.acn.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mayeux R. Biomarkers: potential uses and limitations. NeuroRx. 2004;1:182–188. doi: 10.1602/neurorx.1.2.182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]