Abstract

AIM: To survey gastroenterologists and hepatologists regarding their current views on treating hepatitis C virus (HCV) infected alcoholic hepatitis (AH) patients.

METHODS: A sixteen item questionnaire was electronically mailed to gastroenterologists and hepatologists. A reminder was sent after 2 mo to increase the response rate. Participation of respondents was confidential. Accessing secured web site to respond to the questionnaire was considered as informed consent. Responses received on the secured website were downloaded in an excel sheet for data analysis.

RESULTS: Analyzing 416 responses to 1556 (27% response rate) emails, 57% respondents (56% gastroenterologists) reported HCV prevalence > 20% amongst AH patients. Sixty nine percent often treated AH and 46% preferred corticosteroids (CS). Proportion of respondents with consensus (75% or more respondents agreeing on question) on specific management of HCV infected AH were: routine HCV testing (94%), HCV not changing response to CS (80%) or pentoxifylline (91%), no change in approach to treating HCV infected AH (75%). None of respondent variables: age, specialty, annual number of patients seen, and HCV prevalence could predict respondent to be in consensus on any of or all 4 questions. Further, only 4% would choose CS for treating HCV infected AH as opposed to 47% while treating HCV negative AH.

CONCLUSION: Gastroenterologists and hepatologists believe that AH patients be routinely checked for HCV. However, there is lack of consensus on choice of drug for treatment and outcome of HCV positive AH patients. Studies are needed to develop guidelines for management of HCV infected AH patients.

Keywords: Survey, Alcoholic hepatitis, Hepatitis C virus, Alcoholic liver disease

Core tip: Alcoholic hepatitis (AH) carries about 40%-50% mortality amongst patients with severe disease. Physicians usually shy away from treating AH in presence of concomitant hepatitis C virus (HCV). We surveyed gastroenterologists and hepatologists to assess their practice patterns on treating HCV infected AH patients. We found that although, physicians agree on screening for HCV in these patients, there is lack of consensus on treatment approach. There was no agreement on choice of drug and response to corticosteroids or pentoxifylline amongst HCV infected AH patients. Guidelines are needed on treating AH in presence of HCV.

INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and alcohol-related liver disease (ALD) either alone or in combination are responsible for more than two third of all patients with chronic liver disease in the United States[1]. Alcoholic hepatitis (AH), a distinct entity amongst patients with ALD, occurs in about 35% of heavy drinkers[2]. In its severe form, this disease is associated with significant morbidity, one month mortality of 30%-50%[3-8], and huge economic burden[9]. HCV, the most common bloodstream infection in the United States, affects approximately 3.9 million individuals with a higher prevalence amongst alcoholics[10]. Prevalence of HCV infection is higher amongst alcoholics with liver disease and correlates with its severity[11-20].

Alcohol and HCV together, present in about 10%-15% of patients with chronic liver disease in the United States[21], act synergistically resulting in higher prevalence of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma[22-24], cause more severe and rapid progression of fibrosis[25,26], and have poorer response to antiviral therapy compared to when either of these agents is present alone[27,28]. However, data on the interaction of HCV and AH are scanty. In a single center retrospective study of 76 patients with AH, presence of concomitant HCV infection emerged as an independent risk factor for a poor outcome at 6 mo (Cox proportional hazard ratio 8.45, P = 0.01) after controlling for patient demographics, disease severity at admission, and treatment[29]. Similar data have been reported on the in-hospital mortality in the large national inpatient database analyses[30]. In our retrospective study, we also observed that AH patients were less likely to be treated with specific treatments such as corticosteroids or pentoxifylline in the presence of concomitant HCV infection compared to patients without HCV despite similar disease severity (27% vs 54%, P = 0.05)[29]. This practice of physicians may reflect absence of guidelines for managing AH patients who are concomitantly infected with HCV. To further understand current practice, we conducted survey of gastroenterologists and hepatologists regarding their practice patterns on treating HCV positive AH patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Survey questionnaire

A 16 item multiple choice questionnaire was designed with the aim to assess the responses to specific questions on the management of HCV infected AH patients. Questions specific to management of HCV infected AH patients were: (1) do you routinely test patients with acute AH for HCV infection; (2) does the presence of concomitant HCV infection change the way you treat AH; (3) which treatment option do you prefer for patients with acute AH and concomitant HCV infection; (4) in your opinion, does HCV infection alter the clinical outcome in patients with AH; (5) in your opinion, does HCV affect the response to treatment of AH with corticosteroids; and (6) in your opinion, does HCV affect the response to treatment of AH with pentoxifylline. In order to avoid bias, we mixed these questions with other questions on respondent characteristics and management of AH in general. These questions were: (1) what is your age; (2) what is your primary area of specialty; (3) how many patients of acute AH on an average do you see per year; (4) what percentage of your patients with acute AH are admitted to the hospital; (5) what percentage of those admitted are admitted through the emergency room; (6) among your patients with acute AH, what percentage have needed liver biopsy to establish diagnosis; (7) what percentage of your patients have associated HCV infection; (8) how often do you treat acute alcoholic patients with corticosteroids or pentoxifylline; (9) if you decide to treat, what drug you prefer; and (10) which of the following would make you chose pentoxifylline rather than corticosteroids. Questions were purposely kept simple so as to be able to complete the survey within 5-10 min.

Study population

Gastroenterologists and hepatologists who are members of the American gastroenterological association or American association for study of liver diseases members and involved in clinical patient care were randomly selected for the study. Physicians known to be involved with seeing only pediatric gastrointestinal diseases were also excluded. Similarly surgeons and paramedical staff (pathologists, radiologists, microbiologists and virologists) were excluded. As physicians could be members for both the associations, duplicate entries were excluded from the Microsoft excel sheet.

Administration of questionnaire

The questionnaire was placed on a secure website of the University of Texas Medical Branch intranet. Potential respondents were emailed a request letter explaining the reason and aim for the survey and the mail. The emails were sent out using the merge email option from the Microsoft Outlook Express. Using the individual email address and linking to the last name, it was assured that the email goes out as a personal email. The link to the website was included in the email request letter. Clicking to the link and taking the survey was considered as an informed consent of the respondent to take part in the survey. After completing the survey questions, responses were submitted to the central website by hitting the submission tab. Once in the website, responses were de-identified. To increase the response rate, a maximum of three additional reminder e-mails were sent at an interval of 1 mo each.

Statistical analysis

Responses on the website for each question were transmitted into a Microsoft excel sheet. If a particular question was not answered, it was assumed that the respondents did not know the answer to that question and was recorded as DNK. Responses were analyzed using the Statistical Analysis Software 9.2 (Cary Inc. Englewood NJ, United States). χ2 student’s t-tests were used for analyzing categorical and continuous variables respectively. Logistic regression analyses model was built to assess respondent variable for consensus on specific questions related to management of HCV infected AH. Consensus was defined as 75% or more respondents answering on a particular response option. P value < 0.05 was considered to be of statistical significance. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX, United States.

RESULTS

Respondent characteristics

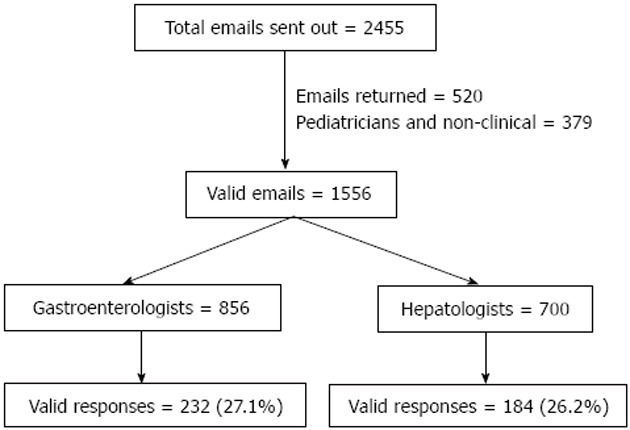

There were 416 responses to 1556 valid emails with a response rate of 27% (Figure 1). Proportion of gastroenterologists was higher than hepatologists (56% vs 44%, P = 0.028) with about 75% of respondents < 55 years of age. About 72% reported seeing < 20 patients of AH per year. More than half responded to seeing over 75% of these patients as hospital admissions and through the emergency room.

Figure 1.

Attrition diagram of valid email responses analyzed for this study.

Physician practice patterns for treating alcoholic hepatitis

About 15% reported need for liver biopsy for diagnosis, 68% would treat AH often with higher proportion reporting use of corticosteroids compared to pentoxifylline (47% vs 37%, P < 0.0001) and 14% using combination of both. The most common reason for choosing pentoxifylline over corticosteroids was presence or concern of infection or sepsis (72%) and 23% also reported concomitant HCV as a reason for choosing pentoxifylline.

Practice patterns on treatment for HCV infected alcoholic hepatitis patients

About 80% would screen AH patients for HCV infection with a higher proportion reporting HCV prevalence ≥ 20% compared to < 20% (49% vs 37%, P = 0.015). The poll was divided on the question of worse outcome of AH in the presence of concomitant HCV infection (P = 0.51). Majority responded that presence of HCV does not change approach to treatment policy and response to corticosteroids or pentoxifylline. However, only 3% would chose corticosteroids for treating HCV positive AH patients (Table 1).

Table 1.

Respondent variables and responses on each question n (%)

| Question | n (%) | DNK | P value |

| Age (yr) | 0.190 | ||

| < 35 | 85 (21) | ||

| 35-44 | 114 (27) | ||

| 45-54 | 112 (27) | ||

| 55-64 | 105 (25) | ||

| Specialty | 0.028 | ||

| Gastroenterology | 232 (56) | ||

| Hepatology | 184 (44) | ||

| Patients (n per year) | 23 (5) | < 0.001 | |

| < 10 | 141 (34) | ||

| 11-20 | 160 (38) | ||

| ≥ 20 | 92 (23) | ||

| Percent admitted to hospital | 39 (9) | < 0.001 | |

| < 25% | 46 (12) | ||

| 26%-50% | 74 (18) | ||

| 51%-75% | 94 (23) | ||

| >75% | 163 (38) | ||

| Of admitted, percent through ER | 44 (12) | < 0.001 | |

| < 50% | 81 (19) | ||

| 51%-75% | 69 (16) | ||

| > 75% | 222 (53) | ||

| Percent needing liver biopsy for diagnosis | 48 (12) | < 0.001 | |

| < 25% | 318 (76) | ||

| 26%-50% | 29 (7) | ||

| > 50% | 21 (5) | ||

| Test AAH patients for HCV | 53 (13) | < 0.001 | |

| Yes | 341 (82) | ||

| No | 22 (5) | ||

| Percent positive for HCV | 58 (14) | 0.015 | |

| < 20% | 156 (37) | ||

| ≥ 20% | 202 (49) | ||

| Treatment for AH | < 0.001 | ||

| Often | 283 (68) | ||

| Rarely | 114 (27) | ||

| Never | 19 (5) | ||

| Drug preference for treatment | < 0.001 | ||

| Corticosteroids | 197 (47) | ||

| Pentoxifylline | 150 (37) | ||

| Combination | 60 (14) | ||

| No preference | 9 (2) | ||

| What makes you choose Pentoxifylline | > 0.05 | ||

| Infection or sepsis | 300 (72) | ||

| GI bleeding | 161 | ||

| Renal failure | 125 | ||

| Hepatitis B | 139 | ||

| Hepatitis C | 94 (23) | ||

| Change in treatment policy with HCV | 84 (20) | < 0.001 | |

| Yes | 83 (20) | ||

| No | 249 (60) | ||

| Treatment preference with concurrent HCV | 79 (19) | < 0.001 | |

| Corticosteroids | 14 (3) | ||

| Pentoxifylline | 114 (27) | ||

| Either | 21 (5) | ||

| Same as without HCV | 180 (44) | ||

| No treatment | 8 (2) | ||

| Does HCV alter outcome of AAH | 80 (19) | 0.510 | |

| No | 174 (42) | ||

| Worse | 161 (39) | ||

| Better | 1 (0.2) | ||

| Does HCV affect treatment response with CS | 87 (21) | < 0.001 | |

| No | 262 (63) | ||

| Worse | 65 (16) | ||

| Better | 2 (0.4) | ||

| Does HCV affect treatment response with PTX | 90 (22) | < 0.001 | |

| No | 297 (71) | ||

| Worse | 3 (0.7) | ||

| Better | 26 (6) |

ER: Emergency room; HCV: Hepatitis C virus; AH: Alcoholic hepatitis; CS: Corticosteroids; GI: Gastrointestinal; PTX: Pentraxin; AAH: Acute alcoholic hepatitis.

On specific questions related to management of HCV infected AH patients, there was consensus (≥ 75% agreement on particular question) amongst respondents for screening of AH patients for HCV (341/363, 94%), concomitant HCV does not change treatment response to pentoxifylline (297/326, 91%), concomitant HCV does not change treatment response to corticosteroids (262/329, 80%), and no change in treatment approach to AH in the presence of concomitant HCV infection (249/332, 75%) (Table 1). On logistic regression analysis, none of the respondent variables of age (≤ 45 years vs > 45 years), specialty (gastroenterology vs hepatology), number of patients seen per year (≤ 20 vs > 20), and prevalence of HCV (≤ 20% vs > 20%) could predict the respondents to be in consensus on any of these 4 questions (Table 2). Further, only less than half of respondents were in agreement on all the four specific questions with lack of prediction by any of the respondent variables (Table 3).

Table 2.

Effect of respondent variables on proportion of respondents being in consensus on each of the four specific questions related to management of hepatitis C virus infected alcoholic hepatitis patients

| Respondent variable |

Routine screening for HCV |

HCV does not change treatment approach |

HCV does not affect response to corticosteroids |

HCV does not affect treatment

response to pentoxifylline |

||||||||

| n (%) | P value | OR (95%CI) | n (%) | P value | OR (95%CI) | n (%) | P value | OR (95%CI) | n (%) | P value | OR (95%CI) | |

| Age (yr) < 35 35-44 45-54 ≥ 55 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.75 | ||||||||

| 68 (92) | 1 | 51 (76) | 1 | 54 (83) | 1 | 59 (91) | 1 | |||||

| 85 (90) | 0.8 (0.3-2.5) | 66 (73) | 1.3 (0.6-3) | 69 (77) | 0.6 (0.3-1.3) | 79 (89) | 0.9 (0.3-2.8) | |||||

| 99 (96) | 2.1 (0.5-8) | 73 (78) | 0.9 (0.4-2) | 75 (81) | 0.7 (0.3-1.6) | 85 (93) | 1.7 (0.5-6) | |||||

| 88 (97) | 2.5 (0.6-11) | 58 (72) | 1.4 (0.6-3) | 63 (79) | 0.6 (0.3-1.5) | 73 (91) | 1.3 (0.4-4.2) | |||||

| Specialty GE HP | 0.37 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.55 | ||||||||

| 183 (93) | 1 | 135 (73) | 1 | 135 (77) | 1 | 160 (92) | 1 | |||||

| 157 (95) | 1.5 (0.6-3.7) | 113 (77) | 0.8 (0.5-1.4) | 126 (83) | 0.7 (0.4-1.2) | 136 (90) | 1.3 (0.6-2.7) | |||||

| Patients (n/yr) < 30 ≥ 30 | 0.29 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.38 | ||||||||

| 299 (93) | 1 | 221 (75) | 1 | 232 (81) | 1 | 259 (91) | 1 | |||||

| 41 (98) | 2.9 (0.4-22.0) | 27 (71) | 1.3 (0.6-2.7) | 29 (73) | 1.6 (0.7-3.3) | 37 (95) | 0.5 (0.1-2.3) | |||||

| HCV prevalence < 20% ≥ 20% | 0.48 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.81 | ||||||||

| 148 (95) | 0.7 (0.3-1.8) | 104 (72) | 0.8 (0.5-1.3) | 119 (83) | 1.4 (0.8-2.5) | 129 (91) | 1.1 (0.5-2.4) | |||||

| 188 (93) | 1 | 143 (77) | 1 | 141 (77) | 1 | 166 (91) | 1 | |||||

HCV: Hepatitis C virus; GE: Gastroenterology; HP: Hepatology. Also shown are results of logistic regression analyses for each respondent variable given as odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI).

Table 3.

Effect of respondent variables on proportion of respondents being in consensus on all four questions related to management of hepatitis C virus infected alcoholic hepatitis patients

| Respondent variable |

Consensus on all four questions related to

management of HCV infected AH patients |

||

| n (%) | P value | OR (95%CI) | |

| Age (yr) | |||

| < 35 | 37 (44) | 1 | |

| 35-44 | 52 (46) | 0.9 (0.5-1.8) | |

| 45-54 | 58 (53) | 0.2 | 1.1 (0.6-3.1) |

| ≥ 55 | 44 (43) | 1.9 (0.5-4.3) | |

| Specialty | |||

| GE | 125 (56) | 1 | |

| HP | 84 (47) | 0.37 | 1.4 (0.97-2.1) |

| Patients (n/yr) | |||

| < 30 | 180 (52) | 1 | |

| ≥ 30 | 22 (49) | 0.29 | 1.1 (0.6-2.1) |

| HCV prevalence | |||

| < 20% | 71 (46) | 0.48 | 0.9 (0.6-1.4) |

| ≥ 20% | 97 (48) | 1 | |

HCV: Hepatitis C virus; GE: Gastroenterology; HP: Hepatology; AH: Alcoholic hepatitis. Also shown are results of logistic regression analysis for each respondent variable given as odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI).

DISCUSSION

About 14% of patients with chronic liver disease have combined alcohol abuse and HCV, and one-third of alcoholics with clinical symptoms of liver disease have been infected with HCV, which is four times the rate of HCV infection found in alcoholics who do not have liver disease[13,31,32]. Prevalence of HCV amongst patients with AH varies from 8% to 22.2%[16,19,33] and varies dependent on geographical areas and explains variation in the prevalence rates in our survey.

There was a lack of consensus on the outcome of AH in the presence of HCV infection. Our initial retrospective study showed HCV to be a strong predictor of mortality at 6 mo amongst AH patients[29]. These data have been confirmed using larger VA and Nationwide Inpatient Sample databases showing higher in-hospital mortality amongst HCV infected AH patients compared to AH patients without HCV infection[30,34]. Studies are suggested looking at the improvement of existing scoring systems with incorporation of HCV into the model. Further, with the availability of non-interferon based regimens for treatment of HCV infection, it would be worthwhile assessing feasibility of these options to improve outcome of HCV infected AH patients.

We found in a previous study that patients with concomitant AH and HCV received specific treatment for AH less often compared with patients with AH alone for all the patients (28% vs 57%, P = 0.014) and for severe disease (41% vs 83%, P = 0.0066)[29]. This is also reflected by our survey where only 3% would chose corticosteroids for treating AH in the presence of HCV infection in contrast to 38% choosing this option for treating AH in general. The presence of HCV infection is not considered a contraindication for using steroids[35], and fear of using corticosteroids may be based on possible harmful effect of corticosteroids on the HCV replication[36-41]. An in vitro study showed lack of effect of steroids on the HCV RNA level[42]. Data in HCV transplanted patients have shown association of steroids use with risk for increased recurrence, worse disease, and progression of fibrosis[43]. However, these effects are seen with bolus doses used for treatment of acute cellular rejection or when steroids are rapidly tapered after using them for long duration (6 mo or more)[44]. In AH, steroids are used for a short period of 1 mo with slow taper later. Randomized studies are suggested comparing slow to rapid taper of steroids on the HCV RNA level and clinical outcomes.

Similar confusion and lack of consensus was also seen when choosing Pentoxifylline, a drug with excellent safety profile. Pentoxifylline has been used on long-term basis in cirrhotics including those with HCV cirrhosis[45]. Not only, the drug was found to be safe but was also beneficial for reducing the liver disease complications especially hepatorenal syndrome[46-48]. This is reflected by the 27% of the surveyed clinician who chose Pentoxifylline as a treatment option although there was general consensus that HCV does not affect AH treatment response.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study addressing current management of concurrent AH and HCV infection. Another strength of the study is limiting survey to gastroenterologists and hematologists who are usually involved to make decisions on management of severe AH. Lack of availability of data on gender and geographical area of respondents limited evaluation of these variables in the survey. Another limitation is keeping the survey anonymous which did not allow us to administer the survey again to check for reliability of the answers. However, this helped us to increase the response rate. Finally, some respondents did not answer to some of the questions and could have resulted in selection or non-response bias. However, we think that missing answers could be due to lack of sufficient AH population in clinical practices of respondents such as in China where HBV is endemic and or Middle East and Saudi Arabia where alcohol is not often used due to religious reasons. There is no minimum acceptable response rate in a survey[49]. But we feel that 27% of response rate from a randomly selected group of gastroenterologists and hepatologists is adequate for the study results and avoid non-response bias.

In summary, our study showed a dissociated opinion amongst gastroenterologists and hepatologists on management of AH in the presence of concomitant HCV infection especially on the choice of drug and outcome of AH. Our findings suggest a clear need for studies to assess the response to treatment with corticosteroids amongst HCV infected AH patients and compare to AH patients without HCV infection in order to develop guidelines for management of AH patients who are also infected with HCV.

COMMENTS

Background

Recent data have shown worse outcome of AH in presence of concomitant hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. Further, many physicians consider HCV to be a relative contraindication for treating alcoholic hepatitis (AH) especially with corticosteroids. Findings of lack of consensus on managing HCV infected AH patients as found in this survey analysis imply need for development of guidelines on management of these patients.

Research frontiers

There are two research frontiers: high prevalence of HCV in AH patients; lack of consensus amongst gastroenterologists and hepatologists on managing HCV infected AH patients.

Innovations and breakthroughs

Lack of data on managing HCV infected AH patients dictates need for studies in this group of patients.

Applications

Need for welld designed studies aiming to develop guidelines for management of HCV infected AH patients.

Peer review

Statistical tests using logistic regression analysis showing that none of respondent variables predicted respondent to be in consensus on questions related to managing HCV infected AH patients.

Footnotes

P- Reviewers Shah V, Jutavijittum P S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Yan JL

References

- 1.Singal AK, Anand BS. Mechanisms of synergy between alcohol and hepatitis C virus. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41:761–772. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3180381584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kulkarni K, Tran T, Medrano M, Yoffe B, Goodgame R. The role of the discriminant factor in the assessment and treatment of alcoholic hepatitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38:453–459. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200405000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mathurin P, Abdelnour M, Ramond MJ, Carbonell N, Fartoux L, Serfaty L, Valla D, Poupon R, Chaput JC, Naveau S. Early change in bilirubin levels is an important prognostic factor in severe alcoholic hepatitis treated with prednisolone. Hepatology. 2003;38:1363–1369. doi: 10.1016/j.hep.2003.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Purohit V, Russo D. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of alcoholic hepatitis: introduction and summary of the symposium. Alcohol. 2002;27:3–6. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(02)00211-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walsh K, Alexander G. Alcoholic liver disease. Postgrad Med J. 2000;76:280–286. doi: 10.1136/pmj.76.895.280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carithers RL, Herlong HF, Diehl AM, Shaw EW, Combes B, Fallon HJ, Maddrey WC. Methylprednisolone therapy in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis. A randomized multicenter trial. Ann Intern Med. 1989;110:685–690. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-110-9-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maddrey WC, Boitnott JK, Bedine MS, Weber FL, Mezey E, White RI. Corticosteroid therapy of alcoholic hepatitis. Gastroenterology. 1978;75:193–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramond MJ, Poynard T, Rueff B, Mathurin P, Théodore C, Chaput JC, Benhamou JP. A randomized trial of prednisolone in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:507–512. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199202203260802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maher J. Alcoholic liver disease. In: Feldman MFL, Sleisenger MH, editors. Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2002. pp. 1375–1391. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alter MJ, Kruszon-Moran D, Nainan OV, McQuillan GM, Gao F, Moyer LA, Kaslow RA, Margolis HS. The prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, 1988 through 1994. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:556–562. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199908193410802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koff RS, Dienstag JL. Extrahepatic manifestations of hepatitis C and the association with alcoholic liver disease. Semin Liver Dis. 1995;15:101–109. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1007267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Befrits R, Hedman M, Blomquist L, Allander T, Grillner L, Kinnman N, Rubio C, Hultcrantz R. Chronic hepatitis C in alcoholic patients: prevalence, genotypes, and correlation to liver disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1995;30:1113–1118. doi: 10.3109/00365529509101616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coelho-Little ME, Jeffers LJ, Bernstein DE, Goodman JJ, Reddy KR, de Medina M, Li X, Hill M, La Rue S, Schiff ER. Hepatitis C virus in alcoholic patients with and without clinically apparent liver disease. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1995;19:1173–1176. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1995.tb01597.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mendenhall CL, Moritz T, Rouster S, Roselle G, Polito A, Quan S, DiNelle RK. Epidemiology of hepatitis C among veterans with alcoholic liver disease. The VA Cooperative Study Group 275. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:1022–1026. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caldwell SH, Li X, Rourk RM, Millar A, Sosnowski KM, Sue M, Barritt AS, McCallum RW, Schiff ER. Hepatitis C infection by polymerase chain reaction in alcoholics: false-positive ELISA results and the influence of infection on a clinical prognostic score. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:1016–1021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sata M, Fukuizumi K, Uchimura Y, Nakano H, Ishii K, Kumashiro R, Mizokami M, Lau JY, Tanikawa K. Hepatitis C virus infection in patients with clinically diagnosed alcoholic liver diseases. J Viral Hepat. 1996;3:143–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.1996.tb00005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prieto Domingo JJ, Carrión Bolaños JA, Bandrés Moya F. [Prevalence of hepatitis C virus and excessive consumption of alcohol in a nonhospital worker population] Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1997;20:479–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.González Quintela A, Alende R, Aguilera A, Tomé S, Gude F, Pérez Becerra E, Torre A, Martínez Vázquez JM, Barrio E. [Hepatitis C virus antibodies in alcoholic patients] Rev Clin Esp. 1995;195:367–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yokoyama H, Ishii H, Moriya S, Nagata S, Watanabe T, Kamegaya K, Takahashi H, Maruyama K, Haber P, Tsuchiya M. Relationship between hepatitis C virus subtypes and clinical features of liver disease seen in alcoholics. J Hepatol. 1995;22:130–134. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(95)80419-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parés A, Barrera JM, Caballería J, Ercilla G, Bruguera M, Caballería L, Castillo R, Rodés J. Hepatitis C virus antibodies in chronic alcoholic patients: association with severity of liver injury. Hepatology. 1990;12:1295–1299. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840120608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Said A, Williams J, Holden J, Remington P, Musat A, Lucey MR. The prevalence of alcohol-induced liver disease and hepatitis C and their interaction in a tertiary care setting. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:928–934. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00393-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Corrao G, Torchio P, Zambon A, Ferrari P, Aricò S, di Orio F. Exploring the combined action of lifetime alcohol intake and chronic hepatotropic virus infections on the risk of symptomatic liver cirrhosis. Collaborative Groups for the Study of Liver Diseases in Italy. Eur J Epidemiol. 1998;14:447–456. doi: 10.1023/a:1007411423766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Corrao G, Aricò S. Independent and combined action of hepatitis C virus infection and alcohol consumption on the risk of symptomatic liver cirrhosis. Hepatology. 1998;27:914–919. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Donato F, Tagger A, Chiesa R, Ribero ML, Tomasoni V, Fasola M, Gelatti U, Portera G, Boffetta P, Nardi G. Hepatitis B and C virus infection, alcohol drinking, and hepatocellular carcinoma: a case-control study in Italy. Brescia HCC Study. Hepatology. 1997;26:579–584. doi: 10.1002/hep.510260308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Poynard T, Bedossa P, Opolon P. Natural history of liver fibrosis progression in patients with chronic hepatitis C. The OBSVIRC, METAVIR, CLINIVIR, and DOSVIRC groups. Lancet. 1997;349:825–832. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)07642-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wiley TE, McCarthy M, Breidi L, McCarthy M, Layden TJ. Impact of alcohol on the histological and clinical progression of hepatitis C infection. Hepatology. 1998;28:805–809. doi: 10.1002/hep.510280330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ohnishi K, Matsuo S, Matsutani K, Itahashi M, Kakihara K, Suzuki K, Ito S, Fujiwara K. Interferon therapy for chronic hepatitis C in habitual drinkers: comparison with chronic hepatitis C in infrequent drinkers. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:1374–1379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Okazaki T, Yoshihara H, Suzuki K, Yamada Y, Tsujimura T, Kawano K, Yamada Y, Abe H. Efficacy of interferon therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Comparison between non-drinkers and drinkers. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1994;29:1039–1043. doi: 10.3109/00365529409094883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singal AK, Sagi S, Kuo YF, Weinman S. Impact of hepatitis C virus infection on the course and outcome of patients with acute alcoholic hepatitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;23:204–209. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e328343b085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singal AK, Kuo YF, Anand BS. Hepatitis C virus infection in alcoholic hepatitis: prevalence patterns and impact on in-hospital mortality. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;24:1178–1184. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e328355cce0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mendenhall CL, Seeff L, Diehl AM, Ghosn SJ, French SW, Gartside PS, Rouster SD, Buskell-Bales Z, Grossman CJ, Roselle GA. Antibodies to hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus in alcoholic hepatitis and cirrhosis: their prevalence and clinical relevance. The VA Cooperative Study Group (No. 119) Hepatology. 1991;14:581–589. doi: 10.1016/0270-9139(91)90042-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takase S, Matsuda Y, Sawada M, Takada N, Takada A. Effect of alcohol abuse on HCV replication. Gastroenterol Jpn. 1993;28:322. doi: 10.1007/BF02779238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tanaka T, Yabusako T, Yamashita T, Kondo K, Nishiguchi S, Kuroki T, Monna T. Contribution of hepatitis C virus to the progression of alcoholic liver disease. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24:112S–116S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chak E, Talal AH, Sherman KE, Schiff ER, Saab S. Hepatitis C virus infection in USA: an estimate of true prevalence. Liver Int. 2011;31:1090–1101. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.02494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lucey MR, Mathurin P, Morgan TR. Alcoholic hepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2758–2769. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0805786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berenguer M. Host and donor risk factors before and after liver transplantation that impact HCV recurrence. Liver Transpl. 2003;9:S44–S47. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2003.50243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McCaughan GW, Zekry A. Impact of immunosuppression on immunopathogenesis of liver damage in hepatitis C virus-infected recipients following liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2003;9:S21–S27. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2003.50269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lake JR. The role of immunosuppression in recurrence of hepatitis C. Liver Transpl. 2003;9:S63–S66. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2003.50264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wiesner RH, Sorrell M, Villamil F. Report of the first International Liver Transplantation Society expert panel consensus conference on liver transplantation and hepatitis C. Liver Transpl. 2003;9:S1–S9. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2003.50268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McCaughan GW, Shackel NA, Bertolino P, Bowen DG. Molecular and cellular aspects of hepatitis C virus reinfection after liver transplantation: how the early phase impacts on outcomes. Transplantation. 2009;87:1105–1111. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31819dfa83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gane EJ, Portmann BC, Naoumov NV, Smith HM, Underhill JA, Donaldson PT, Maertens G, Williams R. Long-term outcome of hepatitis C infection after liver transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:815–820. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199603283341302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Henry SD, Metselaar HJ, Van Dijck J, Tilanus HW, Van Der Laan LJ. Impact of steroids on hepatitis C virus replication in vivo and in vitro. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1110:439–447. doi: 10.1196/annals.1423.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Berenguer M, Ferrell L, Watson J, Prieto M, Kim M, Rayón M, Córdoba J, Herola A, Ascher N, Mir J, et al. HCV-related fibrosis progression following liver transplantation: increase in recent years. J Hepatol. 2000;32:673–684. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80231-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Berenguer M, Aguilera V, Prieto M, San Juan F, Rayón JM, Benlloch S, Berenguer J. Significant improvement in the outcome of HCV-infected transplant recipients by avoiding rapid steroid tapering and potent induction immunosuppression. J Hepatol. 2006;44:717–722. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lebrec D, Thabut D, Oberti F, Perarnau JM, Condat B, Barraud H, Saliba F, Carbonell N, Renard P, Ramond MJ, et al. Pentoxifylline does not decrease short-term mortality but does reduce complications in patients with advanced cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:1755–1762. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.De BK, Gangopadhyay S, Dutta D, Baksi SD, Pani A, Ghosh P. Pentoxifylline versus prednisolone for severe alcoholic hepatitis: a randomized controlled trial. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:1613–1619. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.1613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sidhu S, Singla M, Bhatia K. Pentoxfylline reduces disease severity and prevents renal impairment in severe acute alcoholic hepatitis: a double blind, placebo controlled trial. Hepatology. 2006:4: 373A. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Macavoy N, Forrest E, Hayes P. The influence of Pentoxfylline on mortality in alcoholic hepatitis and benefit of the Glascow Alcoholic Hepatitis Score (GAHS) Hepatology. 2005;42:492A. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Johnson TP, Wislar JS. Response rates and nonresponse errors in surveys. JAMA. 2012;307:1805–1806. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.3532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]