Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to compare clinicopathologic characteristics, surgery outcomes and survival outcomes of patients with stage III and IV mucinous epithelial ovarian cancer (mEOC) and serous epithelial ovarian carcinoma (sEOC).

Methods

Patients who had surgery for advanced stage (III or IV) mEOC were evaluated retrospectively and defined as the study group. Women with sEOC who were matched for age and stage of disease were randomly chosen from the database and defined as the control group. The baseline disease characteristics of patients and platinum-based chemotherapy efficacy (response rate, progression-free survival and overall survival [OS]) were compared.

Results

A total of 138 women were included in the study: 50 women in the mEOC group and 88 in the sEOC group. Patients in the mEOC group had significantly less grade 3 tumors and CA-125 levels and higher rate of para-aortic and pelvic lymph node metastasis. Patients in the mEOC group had significantly less platinum sensitive disease (57.9% vs. 70.8%; p=0.03) and had significantly poorer OS outcome when compared to the sEOC group (p=0.001). The risk of death for mEOC patients was significantly higher than for sEOC patients (hazard ratio, 2.14; 95% confidence interval, 1.34 to 3.42).

Conclusion

Advanced stage mEOC patients have more platinum resistance disease and poorer survival outcome when compared to advanced stage sEOC. Therefore, novel chemotherapy strategies are warranted to improve survival outcome in patients with mEOC.

Keywords: Chemosensitivity, Mucinous epithelial ovarian cancer, Serous epithelial ovarian cancer, Survival

INTRODUCTION

Of all the gynecologic cancers, epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) accounts for 25%-30% of all cases and has the highest fatality-to-case ratio [1]. Primary cytoreductive surgery and taxane/platinum-based adjuvant chemotherapy are the cornerstones of the initial treatment for all histological subtypes of EOC [2,3]. The mucinous cell type accounts for 10% of all primary EOC [4]. The early stages have a better overall prognosis for survival, while the advanced disease is associated with a poorer survival compared to the other histological subgroups [5-8]. The exact mechanism of this finding has not yet been clarified. Either the aggressive characteristic of the tumor or chemoresistance or both mechanisms were claimed to be the reason for poor prognosis of advanced mucinous EOC (mEOC) [9-11]. However, to date, patients with advanced mEOC receive the same treatment as patients with other histologic subtypes of EOC.

In the present study, we aimed to compare the clinicopathologic characteristics and surgery outcomes between patients with advanced stage mEOC and serous EOC (sEOC). We also investigated whether the survival of women with advanced stage mEOC treated with the same protocols is significantly different from that of sEOC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Patient population

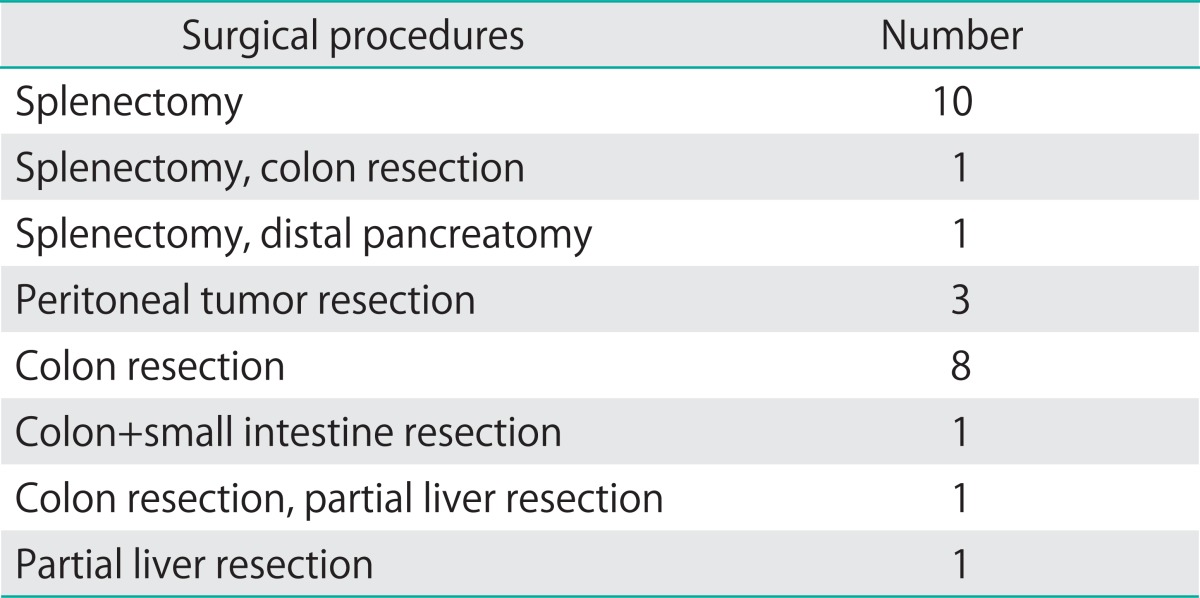

Patients who had surgery for advanced stage (International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics [FIGO] stage III or IV) mEOC at the Gynecologic Oncology Department of Etlik Zübeyde Hanım Women's Health Teaching and Research Hospital and Ankara University Faculty of Medicine between January 1999 and January 2011 were evaluated retrospectively and defined as the study group (Table 1). Women with sEOC who were matched for age, date of diagnosis and stage of disease were randomly chosen from the database and defined as the control group. At surgery, all patients underwent comprehensive surgical staging procedures, including total hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, omentectomy, pelvic and para-aortic lymph node dissection, peritoneal cytology, and peritoneal biopsies according to FIGO guidelines, and also underwent maximal debulking surgery to achieve complete or optimal cytoreduction. Additional performed surgical procedures are presented in Table 2. After the surgery, all patients received platinum based adjuvant chemotherapy. Imaging (usually computed tomography scan or ultrasonography) was performed after every two to three cycles or at the first sign of progressive disease.

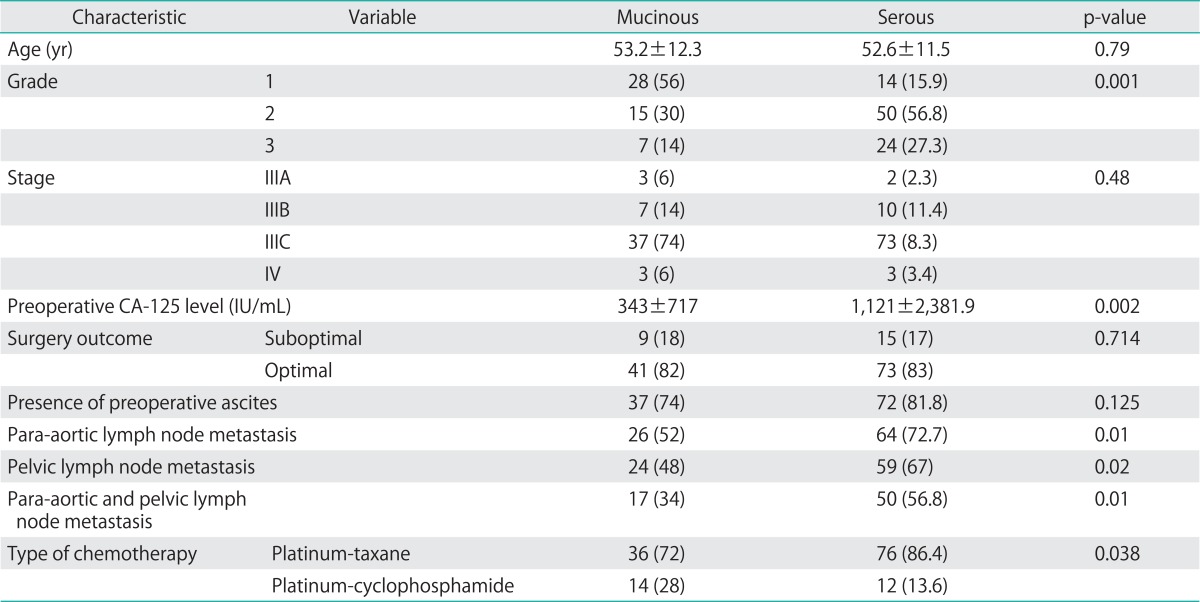

Table 1.

Comparison of both groups according to demographic and clinical features

Values are presented as mean±SD or number (%).

Table 2.

Other surgical procedures performed in addition to total hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, omentectomy, pelvic and para-aortic lymph node dissection, appendectomy

Data were retrospectively extracted from patient charts and computerized medical records. The following parameters were recorded: histology, age, date of diagnosis, stage of disease, grade, presence of ascites and lymph node metastasis, residual disease after primary surgery, serum CA-125 level before and after chemotherapy, chemotherapy regimen (type of platinum-based therapy), number of cycles, response to treatment, time to progression, CA-125 level at recurrence and date of death or last follow-up. In all patients, the diagnosis was confirmed histologically. Patients with borderline EOC, non-seromucinous EOC, non-epithelial ovarian tumors and primary peritoneal tumors were not included in the study. All patients underwent detailed preoperative and surgical exploration to exclude primary colorectal and appendix tumor. In all cases, frozen/section examination was performed and appendectomy was added to the routine procedure if the frozen/section showed "mucinous tumor". Immunohistochemical study was performed in situations where metastatic tumor can not be excluded. With careful exclusion of noninvasive,and metastatic mucinous tumors, patients who had final pathologic diagnosis as "primary mEOC" were included in the study. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee.

2. Definitions

Tumorectomy was defined as resection of the tumor without resection of part or all of the involved organ, which includes optimal and suboptimal cytoreduction. Patients were staged according to FIGO criteria and surgery was defined as optimal if the largest dimension of the largest residual tumor was ≤0.5 cm and suboptimal if the dimension was >0.5 cm [12]. Progression-free survival (PFS) was defined as the time, in months, from the first day of chemotherapy treatment to the date of disease recurrence (confirmed on physical, radiologic or serologic exam). Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time, in months, from the first day of chemotherapy treatment to the date of death, last follow-up, or censoring.

3. Statistical analysis

The primary endpoints of the study were to assess the baseline disease characteristics of patients and to compare platinum-taxane based chemotherapy efficacy (response rate, PFS and OS) in patients with advanced mEOC or sEOC.

Continuous variables were expressed as mean, median, minimum and maximum, whereas percentages and frequencies were used for categorical variables. Groups were controlled in terms of conformity to normal distrubution by graphical check and Shapiro Wilk test. Mann-Whitney test was performed for not normally distributing variables and independent t-test was used for normally distributed variables.

PFS and OS were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and univariate analysis evaluating the risk factors associated with PFS and OS was performed by comparing the PFS and OS rates using the log-rank test. All prognostic variables found to be significant in univariate analysis were included in multivariate analysis using Cox's proportional hazards model. For this procedure, the forward selection of the parameter was processed using the chi-square test score and backward elimination using the Wald test. p-values ≤0.05 in two-sided tests were regarded as significant. Data analysis was carried out using SPSS ver. 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

During the study period, a total of 138 women were included in the study: 50 women in the mEOC group and 88 in the sEOC group. The mean ages of the study and control groups at diagnosis were 53.2±12.3 years and 52.6±11.5 years, respectively. Clinicopathologic characteristics of patients are summarized in Table 1. The groups were not different with regard to age, stage, surgery outcome (optimal vs. suboptimal) and presence of ascites. However, patients in the mEOC group had significantly less grade 3 tumors and lower CA-125 levels compared to the sEOC group (p=0.001). Moreover, patients with sEOC had a significantly higher rate of para-aortic and pelvic lymph node metastasis (p=0.01 and p=0.02, respectively) (Table 1).

Thirty-six (72.0%) patients in the mEOC and 76 (86.4%) in the sEOC group received a taxane+platinum chemotherapy regimen. The median number of cycles in both groups was 6 (range, 2 to 12). Thirty-eight patients (76.0%) in the mEOC group and 65 (78.4%) in the sEOC group had recurrence. Of these patients with recurrence, 57.9% of the patients in the mEOC group had platinum sensitive disease while 70.8% of patients in the sEOC group had platinum sensitive disease. The difference was statistically significant (p=0.03).

The median follow-up period was 40 months (range, 3 to 193 months). Seventy-one (51.4%) patients died of disease, 33 (66.0%) in the mEOC group and 38 (43.2%) in the sEOC group. The difference was statistically significant (p=0.01).

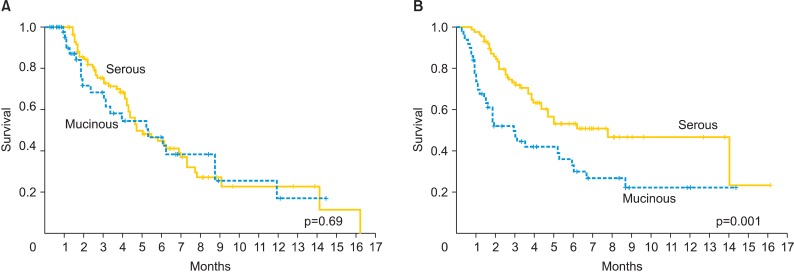

Median PFS was 7 months (range, 6 to 50 months) for patients with mEOC and 11 months (range, 3 to 144 months) for patients with sEOC. The groups were not different (p=0.693) (Fig. 1A). PFS according to chemotherapy regimen (platinum+cyclophospamide vs. platinum+taxane) did not show statistical significance (p=0.322 and p=0.099, respectively).

Fig. 1.

Progression-free survival (A) overall survival (B) for patients with 50 mucinous and 88 serous epithelial ovarian cancer.

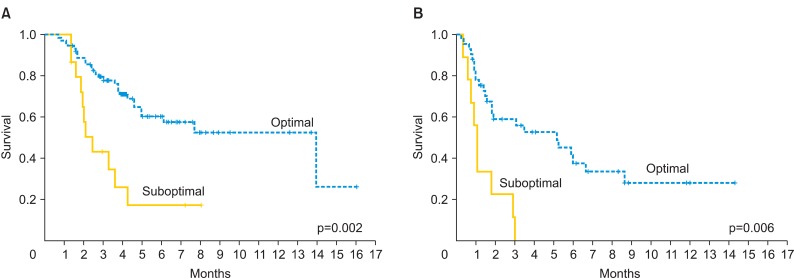

Median OS was 35 and 94 months for patients with mEOC and sEOC, respectively. Women in the mEOC group had a significantly poorer OS outcome when compared to the sEOC group (p=0.001) (Fig. 1B). The risk of death for mEOC patients was significantly higher than for sEOC patients (hazard ratio, 2.14; 95% confidence interval, 1.34 to 3.42). Moreover, patients who had optimal surgery had significantly longer OS in the study and control groups (p=0.002 and p=0.006, respectively) (Figs. 2). In the mEOC group, OS was 3.8 fold increased in patients who had optimal surgery (95% confidence interval, 2.07 to 6.1). OS was higher in both groups for patients who had chemosensitive disease (p=0.001).

Fig. 2.

Overall survival according to surgery outcome for patients with serous (A) and mucinous (B) epithelial ovarian cancer.

DISCUSSION

The poor survival outcome of advanced stage mEOC is the main problem in the treatment of EOC. Previous reports have suggested that mEOC behaves differently from the other histological subtypes of EOC [5-9]. The current treatment modality for advanced stage mEOC is maximal cytoreductive surgery followed by taxane/platinum based adjuvant chemotherapy as utilized in sEOC [2,3]. However, the efficacy of taxane/platinum based adjuvant chemotherapy is controversial, because approximately 70-80% of patients with advanced stage mEOC will have chemoresistant disease [9-11,13].

Hess et al. [13] evaluated 27 advanced stage mEOC patients, and reported a lower response rate to first-line chemotherapy (26.3% vs. 64.9%) and survival outcome (12.0 months vs. 36.7 months) in patients with mEOC when compared to sEOC. Bamias et al. [14] compared the data of 24 mEOC patients to 367 sEOC patients and similarly found a worse prognosis in the mEOC group. Moreover, a meta-analysis including 7 randomized trials with 264 advanced stage mEOC stated that mEOC was an independent predictor of poor prognosis when compared to sEOC [15]. On the other hand, in a study including 47 mEOC cases, a significant lower response rate to chemotherapy was found in the mEOC group (38.5% vs. 70%) than the sEOC group. However, survival and time to tumor progression were not significantly different between the two groups [16]. Similarly, Shimada et al. [11] reported a lower response rate to chemotherapy in mEOC group when compared to those in sEOC group.

Good prognostic factors, such as younger patient age, lower tumor grade and less peritoneal carcinomatosis were reported for mEOC [9,17]. In the present study, patients with mEOC had significantly less grade 3 tumors, lower CA-125 level and less para-aortic and pelvic lymph node metastasis. Despite these good prognostic factors, this case-controlled study confirmed that patients with advanced mEOC had more platinum resistance disease and poorer survival outcome when compared to advanced sEOC.

Optimal debulking is associated with a survival advantage in all EOC types. In 2009, Cheng et al. [18] reported that optimal primary cytoreductive surgery for advanced mEOC was an important prognostic factor for survival. Alexandre et al. [9] compared 54 mEOC cases to 786 sEOC cases and noted that macroscopic complete resection was more frequently achieved in patients with mEOC [19]. However, we did not find a statistical difference with regard to complete resection between patients with mEOC and sEOC. This finding may be due to the low number of patients who had suboptimal surgery. Approximately 80% of patients had optimal surgery in our patient population.

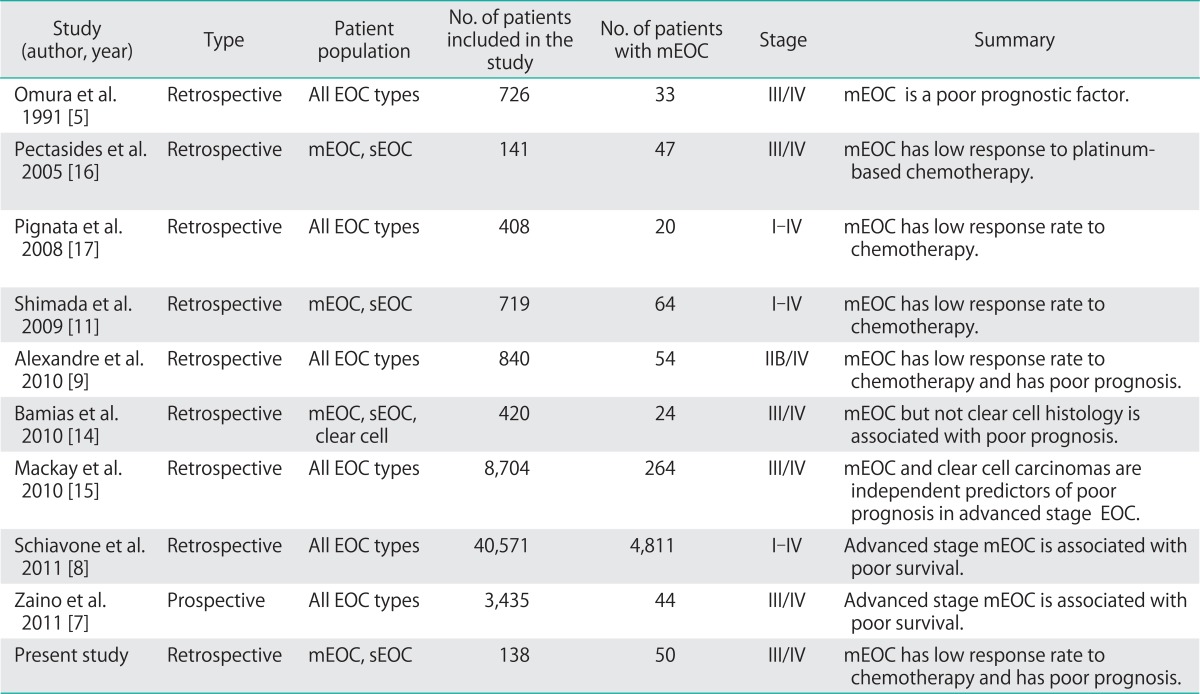

It is hard to draw conclusions in studies evaluating mEOC due to the limited number of studies and the small patient population. Also, our study has several limitations inherent to its retrospective design and small sample size. Although the number of mEOC patients included in the present study is still limited, it is one of the largest studies on advanced stage mEOC thus far. Previous studies which have evaluated the clinicopathologic characteristics of mEOC are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Studies evaluated the clinicopathologic characteristics of mucinous ovarian cancer

mEOC, mucinous epithelial ovarian cancer; sEOC, serous epithelial ovarian cancer.

The main problem with mEOC seems to be the management of patients at an advanced stage due to the reasons described above. The mechanisms leading to this more aggressive course for patients with advanced disease have been studied in limited trials [9,10,13,16]. Failure to respond to platinum-based treatment, as demonstrated here, would explain a poorer survival in mEOC patients, because platinum-sensitivity is one of the main prognostic factors for patients with advanced EOC [10]. The Hellenic Cooperative Oncology Group reported an overall response rate to platinum based chemotherapy of 70% for advanced-stage sEOC compared with only 39% for Meoc [16]. Shimada et al. [11] reported response rates of 13% for invasive mucinous tumors compared with 68% with serous adenocarcinomas. In the present study, response rate to platinum based chemotherapy was 57.9% and 70.8% for patients in mEOC and sEOC groups (p=0.038).

In contrast to these data, patients with advanced stage mEOC receive the same first-line chemotherapy regimen as patients with other histologic subtypes in current practice. However, recent ongoing studies have focused on new chemotherapy strategies for mEOC. The Gynecologic Oncology Group and the Gynecologic Cancer Intergroup have initiated a trial of carboplatin/paclitaxel with or without bevacizumab compared with oxaliplatin/capecitabine with or without be bevacizumab as initial chemotherapy specifically for women with mucinous tumors [20]. Moreover, Japanese researchers are examining a newe agent functions like 5-fluorouracil which has efficacy in vitro [21,22].

In conclusion, our data showed that advanced stage mEOC patients have more platinum resistance disease and poorer survival outcome when compared to advanced stage sEOC. Therefore, novel chemotherapy strategies are warranted to improve survival outcome in patients with mEOC. The results of ongoing prospective studies will shed light on the management of patients with advanced stage mEOC.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Zang RY, Li ZT, Tang J, Cheng X, Cai SM, Zhang ZY, et al. Secondary cytoreductive surgery for patients with relapsed epithelial ovarian carcinoma: who benefits? Cancer. 2004;100:1152–1161. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McGuire WP, Hoskins WJ, Brady MF, Kucera PR, Partridge EE, Look KY, et al. Cyclophosphamide and cisplatin compared with paclitaxel and cisplatin in patients with stage III and stage IV ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199601043340101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bristow RE, Tomacruz RS, Armstrong DK, Trimble EL, Montz FJ. Survival effect of maximal cytoreductive surgery for advanced ovarian carcinoma during the platinum era: a meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1248–1259. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.5.1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan JK, Teoh D, Hu JM, Shin JY, Osann K, Kapp DS. Do clear cell ovarian carcinomas have poorer prognosis compared to other epithelial cell types? A study of 1411 clear cell ovarian cancers. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;109:370–376. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Omura GA, Brady MF, Homesley HD, Yordan E, Major FJ, Buchsbaum HJ, et al. Long-term follow-up and prognostic factor analysis in advanced ovarian carcinoma: the Gynecologic Oncology Group experience. J Clin Oncol. 1991;9:1138–1150. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1991.9.7.1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Teramukai S, Ochiai K, Tada H, Fukushima M. PIEPOC: a new prognostic index for advanced epithelial ovarian cancer: Japan Multinational Trial Organization OC01-01. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3302–3306. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.0114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zaino RJ, Brady MF, Lele SM, Michael H, Greer B, Bookman MA. Advanced stage mucinous adenocarcinoma of the ovary is both rare and highly lethal: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Cancer. 2011;117:554–562. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schiavone MB, Herzog TJ, Lewin SN, Deutsch I, Sun X, Burke WM, et al. Natural history and outcome of mucinous carcinoma of the ovary. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205:480.e1–480.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alexandre J, Ray-Coquard I, Selle F, Floquet A, Cottu P, Weber B, et al. Mucinous advanced epithelial ovarian carcinoma: clinical presentation and sensitivity to platinum-paclitaxel-based chemotherapy, the GINECO experience. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:2377–2381. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakayama K, Takebayashi Y, Nakayama S, Hata K, Fujiwaki R, Fukumoto M, et al. Prognostic value of overexpression of p53 in human ovarian carcinoma patients receiving cisplatin. Cancer Lett. 2003;192:227–235. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(02)00686-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shimada M, Kigawa J, Ohishi Y, Yasuda M, Suzuki M, Hiura M, et al. Clinicopathological characteristics of mucinous adenocarcinoma of the ovary. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;113:331–334. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Griffiths CT. Surgical resection of tumor bulk in the primary treatment of ovarian carcinoma. Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1975;42:101–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hess V, A'Hern R, Nasiri N, King DM, Blake PR, Barton DP, et al. Mucinous epithelial ovarian cancer: a separate entity requiring specific treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1040–1044. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bamias A, Psaltopoulou T, Sotiropoulou M, Haidopoulos D, Lianos E, Bournakis E, et al. Mucinous but not clear cell histology is associated with inferior survival in patients with advanced stage ovarian carcinoma treated with platinum-paclitaxel chemotherapy. Cancer. 2010;116:1462–1468. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mackay HJ, Brady MF, Oza AM, Reuss A, Pujade-Lauraine E, Swart AM, et al. Prognostic relevance of uncommon ovarian histology in women with stage III/IV epithelial ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2010;20:945–952. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181dd0110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pectasides D, Fountzilas G, Aravantinos G, Kalofonos HP, Efstathiou E, Salamalekis E, et al. Advanced stage mucinous epithelial ovarian cancer: the Hellenic Cooperative Oncology Group experience. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;97:436–441. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.12.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pignata S, Ferrandina G, Scarfone G, Scollo P, Odicino F, Cormio G, et al. Activity of chemotherapy in mucinous ovarian cancer with a recurrence free interval of more than 6 months: results from the SOCRATES retrospective study. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:252. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheng X, Jiang R, Li ZT, Tang J, Cai SM, Zhang ZY, et al. The role of secondary cytoreductive surgery for recurrent mucinous epithelial ovarian cancer (mEOC) Eur J Surg Oncol. 2009;35:1105–1108. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2009.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tian C, Markman M, Zaino R, Ozols RF, McGuire WP, Muggia FM, et al. CA-125 change after chemotherapy in prediction of treatment outcome among advanced mucinous and clear cell epithelial ovarian cancers: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Cancer. 2009;115:1395–1403. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trimble EL, Birrer MJ, Hoskins WJ, Marth C, Petryshyn R, Quinn M, et al. Current academic clinical trials in ovarian cancer: Gynecologic Cancer Intergroup and US National Cancer Institute Clinical Trials Planning Meeting, May 2009. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2010;20:1290–1298. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181ee1c01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shimizu Y, Nagata H, Kikuchi Y, Umezawa S, Hasumi K, Yokokura T. Cytotoxic agents active against mucinous adenocarcinoma of the ovary. Oncol Rep. 1998;5:99–101. doi: 10.3892/or.5.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shimizu Y, Umezawa S, Hasumi K. A phase II study of combined CPT-11 and mitomycin-C in platinum refractory clear cell and mucinous ovarian carcinoma. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1998;27:650–656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]