Abstract

The importance of phonological awareness for learning to read may depend on the linguistic properties of a language. This study provides a careful examination of this language-specific theory by exploring the role of phoneme-level awareness in Mandarin Chinese, a language with an orthography that, at its surface, appears to require little phoneme-level insight. A sample of 71 monolingual Mandarin-speaking children completed a phonological elision task and a measure of single-character reading. In this sample, 4- and 5-year-old preschoolers were unable to complete phoneme-level deletions, whereas 6- to 8-year-old first graders were able to complete initial, final, and medial phoneme-level deletions. In this older group, performance on phoneme deletions was significantly related to reading ability even after controlling for syllable- and onset/rime-level awareness, vocabulary, and Pinyin knowledge. We believe that these results reopen the question of the role of phonological awareness in reading in Chinese and, more generally, the nature of the mechanisms underlying this relationship.

Keywords: Phonological awareness, Phonemes, Pinyin, Reading, Mandarin Chinese, Children

Introduction

During the past decade, phonological awareness has become a mainstream concept. Not only has this skill been instantiated in policy and practice (National Reading Panel, 2000; Snow, Burns, & Griffin, 1998), but the concept also has entered children’s homes (e.g., Hooked on Phonics, Leap Frog, Sesame Street), parents’ vocabularies, and schooling agendas. This popularity is merited because phonological skills have been found to be exceptionally important for predicting reading ability (e.g., Adams, 1990; Torgesen, Wagner, & Rashotte, 1994; Wagner & Torgesen, 1987). In fact, phonological awareness is argued to be the single strongest predictor of reading ability in English-speaking children, explaining more than 50% of individual differences in later reading ability even after controlling for age, IQ, and vocabulary (e.g., Lonigan, Burgess, & Anthony, 2000). However, there is still not consensus as to how phonological awareness is related to reading (e.g., Anthony & Lonigan, 2004; Ziegler & Goswami, 2005). The predominant explanation for the relationship between phonological awareness and reading has centered on the interface between spoken and written language (e.g., Katz & Frost, 1992; Perfetti, Liu, & Tan, 2005; Seymour, 2006; Ziegler & Goswami, 2005). To date, there has been strong cross-linguistic support for this explanation (e.g., Goswami, 2008). However, we argue that a few fundamental assumptions in this approach have yet to be tested, assumptions centering on the role of phonological awareness (and phoneme-level awareness in particular) across languages.

How phonological awareness is related to reading: A language-specific approach

The strong version of the language-specific hypothesis argues that the spoken and written properties of a language and the relationship between these two domains determine which linguistic level (i.e., phoneme, onset/rime, or syllable) is the level at which phonological awareness is necessary to learn to read in a given language (e.g., Katz & Frost, 1992). A recent theory by Ziegler and Goswami (2005), the theory of psycholinguistic grain size, operationalizes how the particular properties of a language may constrain the ways in which phonological awareness is related to reading. Specifically, this theory proposes three dimensions of a linguistic system that influence which skills predict reading ability in a language (Ziegler & Goswami, 2005). The first is the linguistic grain size (or granularity) at which phonology is mapped to orthography in a particular language (i.e., syllable, onset/rime, phoneme). The second is the consistency of this mapping. The third is the availability of this linguistic level in spoken language. The theory provides testable claims that, for the most part, have found strong support in the reading literature.

There is strong evidence, for instance, that the linguistic level at which the sounds and graphemes of a language are related is an important factor in reading acquisition. For languages where the mapping between sounds and symbols occurs at the level of the phoneme, such as Italian (e.g., D’Angiulli, Siegel, & Serra, 2001), Turkish (e.g., Durgunoglu & Oney, 1999), and English (e.g., Wagner, Torgesen, & Rashotte, 1994), phoneme-level awareness has been found to be strongly predictive of differences in reading ability. In contrast, for languages where the mapping does not occur at the level of the phoneme, phoneme-level awareness has appeared to be less important in reading acquisition (e.g., Goetry, Urbain, Morais, & Kolinsky, 2005; Huang & Hanley, 1997; Read, Zhang, Nie, & Ding, 1986).

The consistency of the sound–symbol mappings in a language has also proved to be influential. In languages with a highly regular or transparent sound–symbol system, such as Italian and Spanish, phoneme-level awareness develops earlier and is related to reading ability for a shorter period of time than in less transparent languages, such as French and English (e.g., Goswami, Gombert, & de Barrera, 1998). Lastly, there is strong evidence that languages differ in whether their spoken features serve to highlight (or obscure) phonological features important for reading. In a cross-linguistic comparison of English and 12 other European languages, Seymour, Aro, and Erskine (2003) found that children who learned languages with simple syllable structures (no consonant clusters) such as Finnish were faster and more accurate at reading a list of simple nonwords than were children who learned languages with complex syllable structures such as English. Based on this, they proposed that complex syllable structures may obscure phoneme-level information. Other researchers have argued exactly the opposite, namely, that the spoken language processing demands of complex syllable structures heighten phoneme-level awareness (Caravolas & Bruck, 1993; Durgunoglu & Oney, 1999). Regardless of one’s perspective, there is evidence that the structure of the spoken language affects children’s developing awareness of the sounds within their language and that there is an interaction between the availability of this information and the consistency and granularity of the language that influences children’s reading development.

How phonological awareness is related to reading: Limitations of a language-specific approach

The theory of psycholinguistic grain size provides an elegant method for identifying language-specific influences on reading development and for predicting how and when phonological awareness is related to reading in a particular language. Past and present research has provided strong confirmation of this theory; however, we caution that there are still several limitations to the current empirical work. In particular, although research in languages without linguistic features privileging the phoneme (e.g., Chinese) have shown little importance of phoneme-level awareness for predicting reading skills (e.g., Siok & Fletcher, 2001), few studies to date have tested “pure” phoneme-level awareness or awareness that does not also correspond to onset/rime-level awareness (e.g., Shu, Peng, & McBride-Chang, 2008). In the current study, we provide such a test by exploring the relationship between reading ability and pure phoneme-level awareness in emergent Chinese readers. We proposed to examine reading in Mandarin-speaking children because the structural properties of spoken and written Mandarin Chinese and the mapping between these two are uniquely suited to provide one of the strongest possible contrasts to phoneme-centric languages (Wang & Cheng, 2008).

Review of the structure of Mandarin Chinese along the dimensions of granularity, consistency, and availability

The Chinese writing system represents an interesting and important contrast to an alphabetic system such as English (Perfetti et al., 2005). In Chinese, characters represent syllables and morphemes rather than individual phonemes, giving the language a morpho-syllabic structure rather than an alphabetic structure (McBride-Chang, 2004; Ramsey, 1987). In addition, the consistency of the Mandarin Chinese sound–symbol mapping is fairly opaque. Roughly 80% of characters are semantic–phonetic compounds and, thus, contain a component signaling meaning and a component signaling pronunciation, each of which varies in the reliability with which it represents this information (Shu, 2003; Shu & Anderson, 1999; Shu, Chen, Anderson, Wu, & Xuan, 2003). The semantic component cues the meaning (but not the sound) of more than 80% of characters providing important categorical information (e.g., Shu et al., 2003; Tan & Perfetti, 1998). In contrast, the phonetic component cues the pronunciation in less than 40% of compound characters (Ni, 1982, and Zhou, 1978, cited in Shu et al., 2003). However, the reliability of the phonetic is better in the characters that children learn in elementary school (Shu et al., 2003). In School Chinese (the national corpus of characters used for instruction between first and sixth grades (Shu et al., 2003)), the pronunciation of roughly 75% of the compound characters can be deduced from full or partial information contained in the phonetic (i.e., in the compound character

, the phonetic

, the phonetic

provides information about the rime). Thus, the regularity and consistency in the characters children learn in elementary school may signal to the beginning reader a system for how to learn new words. However, this phonological cuing occurs at the level of the syllable or the onset/rime and never at the level of the phoneme.

provides information about the rime). Thus, the regularity and consistency in the characters children learn in elementary school may signal to the beginning reader a system for how to learn new words. However, this phonological cuing occurs at the level of the syllable or the onset/rime and never at the level of the phoneme.

The properties of the spoken language seem to provide no phonemic-level insight either. Mandarin has a simple syllable structure. Consonant clusters do not exist (Duanmu, 2000), and most syllables contain a consonant onset (with some containing only the following parts) followed by a rime containing a nuclear vowel and additional optional vowels and/or an optional consonant (Anderson, Li, Ku, Shu, & Wu, 2003). Within this structure, there are only two viable consonants for the syllable-final position: /n/ and /η/ (Anderson et al., 2003). Thus, in Mandarin Chinese, there are a large number of open syllables (CV) constituting up to 54% (by some estimates) of syllable types compared with only 38% of Mandarin syllables containing a final consonant (CVC and VC) (Wang & Cheng, 2008).

There are several ramifications of this type of syllable structure, but one of the most important (for our purposes) is that consonant clusters in a language may serve to highlight or necessitate speech processing at the level of the phoneme (e.g., Seymour et al., 2003; but see also Caravolas & Bruck, 1993). Cheung, Chen, Lai, Wong, and Hills (2001) extended this argument and proposed that the performance differences observed on phoneme awareness tasks between English- and Mandarin-speaking children were due to the existence of initial consonant clusters in English but not in Mandarin. Thus, according to one interpretation, the simple syllable structure of Mandarin is one way in which the spoken features of the language do not favor phoneme-level processing.

One additional and potentially important feature typifying Chinese spoken and written language is the high level of morphological compounding that now exists in Mandarin (Packard, 2000; Ramsey, 1987). In all languages, morphemes, the smallest units of meaningful speech (Sternberg, 2003), are manipulated in regular speech to produce any number of different lexical transformations—changes in inflection (e.g., adding s to change cat to cats), in derivation (e.g., adding ter to change bat to batter), and in compounding (e.g., adding sun to light to produce the new word sunlight). Languages differ in the extent to which they use specific types of morphology. In Mandarin, morphological compounding is common (Packard, 2000; Ramsey, 1987); nearly 80% of all Mandarin words are polymorphemic (Taft, Liu, & Zhu, 1998). Furthermore, there are regularities in the sound–symbol relations of morphological compounds in Mandarin. However, unlike the components of compound characters (the phonetic and semantic components described above), the characters in compound words are nearly always pronounced the same individually as when in the compound form (Hoosain, 1991; Hu & Catts, 1998). Thus, phonological information in Chinese may be a reliable guide to pronunciation of morphological compounds, but only at the level of the syllable.

Given these properties of Mandarin Chinese, if there is a language-specific relationship between phonological awareness and reading in Chinese children, it should be restricted to the syllable level of representation and, to a lesser degree, the onset/rime due to the regularities at this level (particularly in early character learning). This is a hypothesis that, to date, has found strong support in the literature.

How phonological awareness is related to reading in Chinese: What research has shown

A large number of studies have examined the role of phonological awareness in Chinese readers at the level of the syllable (e.g., McBride-Chang & Ho, 2005). In these studies, both cross-sectional designs (McBride-Chang, Bialystok, Chong, & Li, 2004; McBride-Chang & Ho, 2000; McBride-Chang et al., 2008) and longitudinal designs (Chow, McBride-Chang, & Burgess, 2005; McBride-Chang & Ho, 2005) have found syllable awareness to be the strongest predictor of character reading, predicting up to 20% of the variance in character recognition in 3- to 6-year-olds even after controlling for other phonological measures (working memory and rapid naming), vocabulary, and nonverbal IQ.

Researchers have also investigated awareness at the level of the onset/rime (Siok & Fletcher, 2001). In both cross-sectional analyses (Chen et al., 2004; Leong, Tse, Loh, & Hau, 2008; McBride-Chang et al., 2004, 2005; Shu et al., 2008; So & Siegel, 1997) and longitudinal analyses (Ho & Bryant, 1997a, 1997b; Hu & Catts, 1998), onset and/or rime awareness predicted reading ability in 3- to 8-year-olds even after controlling for other phonological processing skills (working memory and rapid naming), vocabulary, and nonverbal IQ. This suggests that the heightened orthographic consistency of the phonetic at the level of the onset/rime (particularly in early character learning) may be an important and useful analytical tool in learning to read (Leong, Cheng, & Tan, 2005).

Only a handful of studies have compared the relative contributions of syllable and onset/rime awareness to reading. These studies provide preliminary evidence that syllable awareness is a stronger predictor of individual differences in reading than onset/rime awareness overall (e.g., McBride-Chang et al., 2004, 2008). However, recent research suggests that this relationship may change over time, such that with the onset of reading, rime awareness becomes more important (e.g., Shu et al., 2008).

Little research has explored phoneme-level awareness in Chinese children. There is no obvious theoretical relationship between phoneme-level awareness and reading ability given the linguistic structure of Mandarin and Cantonese and the morpheme-level mapping of Chinese script (e.g., McBride-Chang et al., 2005, 2008). In fact, research in adult readers has demonstrated that phoneme-level awareness is nearly inaccessible to Chinese adults without explicit training in a phonemic coding system such as Pinyin (Read et al., 1986), is not related to individual differences in reading ability (Holm & Dodd, 1996), and does not distinguish reading-disabled children from non-reading-disabled children (Shu, McBride-Chang, Wu, & Liu, 2006).

Only a few studies have measured phoneme-level awareness in children1 (Huang & Hanley, 1994, 1997; Leong et al., 2005; Li, Shu, McBride-Chang, Liu, & Xue, 2009; Lin et al., in press; Siok & Fletcher, 2001). However, because the testing items are not always reported in these articles, it is not clear which of these studies have measured what we are calling “pure” Chinese phoneme-level awareness or phoneme awareness that does not also correspond to onset/rime awareness. Because of the simple structure of the Chinese syllable (54% CV in structure), most initial and final deletions are also onset/rime deletions. For example, in the word ke, the initial sound /k/ is both the onset and the initial phoneme. Furthermore, because of the restricted syllable structure, there are only two types of consonantal deletions in the word-final position, n or η, thereby limiting the potential range in final deletions.

If we consider only studies where it is clear that phonological awareness was measured by pure phoneme-level tasks in Chinese words (Huang & Hanley, 1997; Leong et al., 2005; Li et al., 2009; Siok & Fletcher, 2001), the results show that phoneme-level awareness is low in Chinese participants, particularly when compared with English speakers (e.g., Huang & Hanley, 1997). Moreover, in children, there appears to be little or no relationship between phoneme-level awareness and reading, particularly when compared with other levels, such as syllable and onset/rime awareness (e.g., Huang & Hanley, 1997; Siok & Fletcher, 2001; but see Leong et al., 2005), or when compared with other skills (Li et al., 2009). Thus, to date, there is little evidence that pure phoneme-level awareness is an important predictor of reading differences in Chinese readers, particularly when compared with other, larger phonological grain sizes.

Furthermore, the relationship between phoneme-level awareness and reading appears to be highly dependent on the phonological training (e.g., Pinyin, Zhu-Yin-Fu-Hao) that some children receive in school (e.g., Huang & Hanley, 1994,, 1997; Leong et al., 2005; Lin et al., in press). Pinyin and Zhu-Yin-Fu-Hao provide a Romanization of Chinese characters. Chinese children living in mainland China receive Pinyin training typically during the third year of kindergarten before the onset of formal reading training. Research has found that this training appears to improve awareness at the level of the onset and/or rime and even at the level of the phoneme (e.g., Chen et al., 2004; Huang & Hanley, 1997; Leong et al., 2005; Siok & Fletcher, 2001). Moreover, this training has been found to increase the strength of the relationship between phonological awareness and reading ability (Holm & Dodd, 1996; McBride-Chang et al., 2004; Siok & Fletcher, 2001) and may in fact mediate this relationship in Chinese readers (e.g., Huang & Hanley, 1994, 1997; Leong et al., 2005; Lin et al., in press).

Thus, existing research in Chinese readers provides evidence in support of the theory of psycholinguistic grain size and the larger language-specific approach. First, there is converging evidence that both syllable and onset/rime awareness are unique predictors of reading ability in Chinese children but that phoneme-level awareness is difficult and not typically related to reading outcomes. Furthermore, other component skills of reading, skills more related to the structural properties of the language, have been found to be stronger correlates of reading in Chinese-speaking children than have traditional phonological awareness measures. However, there are several issues that still need to be clarified to conclude that there is no role for phoneme-level awareness in the development of reading skills in Chinese children.

How is phonological awareness related to reading in Chinese? What research still needs to show

Phonological awareness is a critical measure in reading research, but one that has not received consistent treatment in the literature on reading in Chinese children. First, as discussed above, little research has examined pure phoneme-level manipulations in Chinese. Furthermore, there is wide variability in the types of phonological tasks used (from low-level sensitivity measures, such as detecting the odd word out [e.g., Ho & Bryant, 1997a, 1997b], to higher level phonological manipulations, such as syllable and onset/rime deletions [e.g., Chow et al., 2005; McBride-Chang & Kail, 2002; McBride-Chang et al., 2004]), in the ages of the children tested (Li et al., 2009; McBride-Chang et al., 2005, 2008), and in the levels of exposure to English (e.g., Huang & Hanley, 1994, 1997) or to a phonological coding system such as Pinyin (Siok & Fletcher, 2001). Because these are all features found to affect children’s phonological awareness (e.g., McBride-Chang et al., 2004), it is difficult to draw firm conclusions about the role of phoneme-level awareness in children learning to read in Chinese. Thus, we suggest that some important next steps are (a) to examine phonological awareness at the level of individual phonemes, as separate from syllables or onset/rimes, in the way shown to be so potent in alphabetic languages (e.g., McBride-Chang, 1996) by requiring explicit manipulation of sound segments ranging from large to small (syllable–phoneme); (b) to use this measure in the age range critical for learning to read (in preschool- and young elementary school-aged Chinese children); and (c) to ensure that the children tested have no exposure to English, in particular, or any alphabetic language.

In the current study, we provided such a test. Specifically, we examined the importance of phonological awareness in predicting reading in monolingual Mandarin-speaking 4- to 8-year-olds using a phonological task requiring explicit manipulation of sound segments of differing sizes (syllable, onset/rime, and phoneme). With the use of this design, we proposed a test of the theory of psycholinguistic grain size and, more generally, the language-specific hypothesis. If Mandarin-speaking children do not have phoneme-level insights, or if there is no relationship between phoneme-level awareness and reading, this lends critical support to the account of psycholinguistic grain size. In contrast, if Chinese children exhibit phoneme-level awareness and this skill is predictive of individual differences in reading beyond measures of syllable and onset/rime awareness, this would prove to be difficult to interpret based on a strong interpretation of the psycholinguistic grain size but would also provide interesting insights into the potency of phoneme-level awareness universally.

Method

Participants

In total, 75 Mandarin-speaking children were recruited directly from a local preschool and primary school in downtown Beijing, China. Of the 75 children with permission to participate, 8 were reported to have learned a nonstandard variant of Mandarin as their first language. All 8 were included in the current analyses because the dialects learned were from provinces in northern China (inner China north of the Yangtze River) and are considered to be variants of Northern Mandarin (Ramsey, 1987). However, 4 children were excluded from the analyses: 2 whose native language was not Mandarin (either Korean or Mongolian) and 2 who were identified as having a history of developmental delays. The mean age of the remaining 71 children was 73 months (range = 49–102). Of these participants, 42% were in their second year of kindergarten, called middle kindergarten, and 58% were enrolled in first grade. Of the remaining participants, all were reported to be monolingual native speakers of Mandarin with no history of language, hearing, or reading impairments and no history of exposure to English (although the caregiver report showed that in 2 cases English was used in the home < 1% of the time). All children were Han Chinese, the ethnic majority of mainland China.

To explore the development of reading skills, we subdivided the sample into a younger group and an older group based on grade level (e.g., Morrison, Smith, & Dow-Ehrensberger, 1995). In mainland China, children are in kindergarten for 3 years. They are enrolled in K1 at around 3 years of age and complete K3 at around 6 years of age. In the current study, the younger group consisted of 30 Mandarin-speaking children in their second year of kindergarten (K2) ranging in age from 49 to 63 months with a mean age of 55.88 months (SD = 3.52). The older group consisted of 41 Mandarin-speaking children in first grade ranging in age from 75 to 102 months with a mean age of 86.38 months (SD = 6.41).

The division in our sample generally aligned with differences in reading instruction and, by proxy, reading levels. At the time of testing in Beijing, Pinyin training was provided during the third year of kindergarten and formal reading instruction began in the first grade of primary school (Li & Rao, 2000), although children also started acquiring a small sight vocabulary earlier. Thus, in the current sample, the younger group of Mandarin-speaking children typically had not yet received any formal reading instruction and demonstrated little reading ability, whereas the older group of Mandarin-speaking children had at least 3 months of formal reading instruction and were trained in Pinyin (McBride-Chang & Kail, 2002).

Materials

In the current study, we examined the relationship between phonological skills and reading ability in emergent Chinese readers.

Phonological awareness

To measure syllable-, onset/rime-, and phoneme-level awareness, we adapted the elision subtest from the Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing (CTOPP) (Wagner, Torgesen, & Rashotte, 1999) for administration in Mandarin Chinese. In this adaptation, we attempted to create a closely related form of the elision task by using Chinese words and nonwords that were roughly parallel to the English forms in familiarity as well as including deletions of the same type and degree of difficulty. However, controlling for difficulty proved to be difficult given the structural properties of Mandarin Chinese.

First, because there are no consonant clusters in Mandarin, the initial consonant in a Chinese word always corresponds to an onset. However, glides are common in Mandarin, and this linguistic feature provides a way in which to disentangle the structural confound between onsets and initial phonemes. A glide is a vowel (in Mandarin: i, u, and y) that precedes the nuclear vowel and is considered to be part of the onset of a word (Duanmu, 2000). Based on this feature, we used only words that were CG(V)X (where X corresponds to either a vowel or a consonant) in structure. We tested onset deletions by requiring children to delete the CG from a CGVX word and tested initial deletions by requiring children to delete the C from a CGVX word. For example, an initial deletion would require children to say xian1 (/sian/)2 without the /s/ to produce the word yan1 (/yan/). In contrast, an onset deletion would require children to say xian1 without the /si/ to produce the word an1 (/an/). Interestingly, the onset /si/ is the Pinyin name for the letter x. So, by separating the initial consonant from the subsequent glide, we also ensured that there was no overlap between initial deletions and the Pinyin representations for these initial consonants. In this manner, we attempted to distinguish onsets from initial phonemes and to distinguish initial phonemes from their Pinyin names in Mandarin Chinese. Although this is a very rigid definition of initial phoneme deletion, it is necessary given the hypotheses of this study even though it might not be as strictly applied in phonological testing in studies in English and, therefore, may also prove to be a more difficult measure of initial phoneme awareness than is typical. Nonetheless, the phoneme-level items were presented in this study by deleting only the initial phoneme rather than the full onset; thus, children were tested on pure phoneme-level awareness for these items.

Second, given the simple syllable structure of Mandarin and the restricted number of consonants possible in the word-final position, the ways in which to create final deletions were limited. Given this, it is conceivable that the reduced number of final consonants makes final phoneme deletions in Mandarin Chinese easier than they might be in English for U.S. children, although this is an empirically testable question.

Lastly, designing medial deletions of comparable difficulty to those used on the CTOPP proved to be difficult. In Mandarin Chinese, a medial deletion can be created only by deleting a phoneme from a diphthong or triphthong (e.g.,

),3 or deleting a phoneme (e.g.,

),3 or deleting a phoneme (e.g.,

) or glide (e.g.,

) or glide (e.g.,

) from a glide–vowel. These types of deletions are particularly challenging and certainly more difficult than the medial deletions on the English form (particularly those that occur at the syllable boundaries; e.g., say driver / dra ɪvr/without saying /v/ = /draɪr/) or in the interior portion of an onset cluster (e.g., say snail /sneɪl/ without saying /n/ = /seɪl/) or a final cluster (e.g., say box

) from a glide–vowel. These types of deletions are particularly challenging and certainly more difficult than the medial deletions on the English form (particularly those that occur at the syllable boundaries; e.g., say driver / dra ɪvr/without saying /v/ = /draɪr/) or in the interior portion of an onset cluster (e.g., say snail /sneɪl/ without saying /n/ = /seɪl/) or a final cluster (e.g., say box

without saying /k/ =

without saying /k/ =

). Nonetheless, it was possible to create these items and to test for children’s medial phoneme deletion abilities in this study.

). Nonetheless, it was possible to create these items and to test for children’s medial phoneme deletion abilities in this study.

In total, there were 54 items on our adapted form of the phonological awareness test. However, for the purpose of testing the specific hypotheses set forth in this article, we report only a subset of 38 items. We excluded 16 items from the current analysis because they required deletions from words that were either CV (3 initial deletions, 4 final deletions), CVV (2 initial deletions), CVC (2 rime deletions), or CGV (5 initial deletions) in structure. Based on the arguments outlined earlier, we did not include items where phoneme deletions corresponded to onset/rime deletions and, thus, do not report children’s performance on the deletions of the first three types listed (CV, CVV, and CVC). Moreover, although the last type of deletion (initial deletions from CGV) conformed to our strict definition of initial phoneme deletions, we did not include these given the difference in structure between these items and the items used in the final and medial deletions (C(G)VX).

Of the remaining 38 items, 18 required syllable-level deletions, 6 required sub-syllabic-level deletions, and 14 required phoneme-level deletions (see Table 1). In the syllable-level deletions, children were required to delete syllables from the initial, medial, or final position in both two- and three-syllable Chinese words to produce words and nonwords, similar to phonological deletion tasks used by other researchers (e.g., McBride-Chang, 2004). In the sub-syllabic-level and phonemic deletions, children were required to delete onsets, rimes, or phonemes (initial, medial, and final) from single-syllable Chinese words to produce words and nonwords.

Table 1.

Types of items used in the phonological awareness task.

| Example | Number of items | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Syllable (N = 18) | Two syllables | Three syllables | |

| Initial | bai2fan4 without bai2 = fan4 | 4 | 4 |

| Final | sha1yu2 without yu2 = sha1 | 6 | 2 |

| Medial | da4men2kou3 without men2 = da4kou3 | 0 | 2 |

| Sub-syllabic (N = 6) | |||

| Onset (CG_VC) | qiang3 without /tɕh/ = ang3 | 3 | |

| Rime (CG_VC) | guan1 without /an1/ = gu1 | 3 | |

| Phonemic (N = 14) | |||

| Initial (C_G(V)C) | xian1 without /s/ = ian1 | 6 | |

| Medial (CGVX) | nuan3 without /a/ = nun3 | 6 | |

| Final (C(G)V_C) | xin1 without /n/ = xi1 | 2 |

Administration followed the testing instructions of the formal CTOPP elision subtest (Wagner et al., 1999), but testing was discontinued after 10 consecutive incorrect answers (instead of 6). Furthermore, because of the potential for variation in how tightly experimenters might conform to phoneme-level versus onset/rime-level deletions, we used a single native Mandarin-speaking female to record the items beforehand and during testing administered the prerecorded items individually to children over sound-canceling headphones. Thus, all children heard exactly the same stimuli (in exactly the same sequence) so as to control for the precision and consistency in the presentation of these items. The test had a maximum score of 38 and a reliability of α = .95.

Pinyin knowledge

Knowledge of Pinyin was assessed in Mandarin speakers using 22 lowercase letters and letter pairs. All consonants of the Roman alphabet were assessed except v (because it is not present in Mandarin) and x (because it is a problematic sound in English, and this assessment was part of a larger study (Newman, Tardif, Jingyuan, & Shu, unpublished manuscript, 2010) designed for both English- and Mandarin-speaking children. The letter pairs ch (Mandarin phoneme

), sh (Mandarin phoneme

), sh (Mandarin phoneme

), and zh (Mandarin phoneme

), and zh (Mandarin phoneme

) were added because they are phonemes that are represented in Pinyin. For this task, children were instructed to name the Pinyin of each lowercase letter pair (only lowercase letters are used in Pinyin) presented individually on the computer screen. A total score of 22 points was possible, and the task had a reliability of α = .99.

) were added because they are phonemes that are represented in Pinyin. For this task, children were instructed to name the Pinyin of each lowercase letter pair (only lowercase letters are used in Pinyin) presented individually on the computer screen. A total score of 22 points was possible, and the task had a reliability of α = .99.

Visual–spatial reasoning: Block design

We administered the block design subtest of the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence–Revised (WWPSI-R) (Wechsler, 1989) as a general measure of nonlinguistic competency. This task required participants to recreate various block formations within a specific time period. Administration and scoring followed the instructions in the WWPSI-R testing manual translated for administration in Chinese (Wechsler, 1989) with the exception that the scores were not age normalized into IQ scores. Instead, z scores were computed to standardize children’s performance within each age group. The task had a maximum score of 68 and a reliability of α = .85.

Vocabulary

In the current study, we administered the vocabulary subtest from the Hong Kong Stanford–Binet Intelligence Scale (Thorndike, Hagen, & Sattler, 1986) adapted for Mandarin speakers. The task required participants to define 32 words of increasing conceptual difficulty. Responses were recorded by hand and scored by an independent native Chinese speaker. Each response was scored as 0 (incorrect), 1 (partially correct), or 2 (correct) based on the scoring instructions of the Stanford–Binet Intelligence Scale (Thorndike et al., 1986) for a total maximum score of 64 points. Testing was discontinued when a score of 0 was obtained on 6 consecutive items. Again, scores were not age normalized into IQ scores; instead, z scores were computed to standardize children’s performance within each age group. The task had a reliability of α = .86.

Single-character reading

There is not yet a standardized test of character reading for children living in mainland China. Thus, we administered a single-character reading test that has been used in several other studies of reading ability of children in mainland China (e.g., Shu et al., 2008). The test was composed of 120 characters selected from language textbooks used in primary school in Beijing (Shu et al., 2003). In total, 20 items were chosen for each grade level (first through sixth grades). The first 20 items that were selected to be representative of first-grade reading were also chosen to be orally familiar to kindergartners (formal reading instruction does not begin until first grade). Children were shown characters of increasing difficulty one at a time on a computer screen and were asked to read each character. Testing was discontinued after 10 consecutive wrong answers. This test had a reliability of α = .99.

Procedure

Children were tested in a single session in a typical laboratory testing room or a small quiet school room by trained undergraduate or graduate psychology students. The tasks were administered in the following sequence: vocabulary, single-character reading, block design, elision, and Pinyin knowledge. (These tasks were part of a larger battery reported in Newman et al. (unpublished manuscript, 2010)). Formal breaks were built into the testing so as to avoid fatigue, with additional breaks encouraged if children showed signs of tiring or inattention. Measures were administered either in front of the computer or across from the experimenter at a table in the same testing room. After each testing session, children were given a small prize.

Results

The purpose of this study was to test the extent to which the relationship between phonological awareness and reading ability is influenced by the structural properties of a language system. As described in this section, we conducted a series of analyses to examine the nature of phonological awareness in Mandarin-speaking emergent readers. Our analyses were designed to address three questions:

Do Mandarin-speaking children demonstrate phoneme-level awareness?

Which linguistic levels of phonological awareness are most predictive of reading ability?

Does Pinyin knowledge mediate the relationship between phonological awareness and reading?

Descriptive statistics

Table 2 displays the means and standard deviations of the reading and reading-related measures used in the study for the younger and older children separately. The measures demonstrated good variability and strong reliability with a few exceptions. As expected, performance on the Pinyin knowledge task was at floor in the younger group consisting of children who had not yet received training in Pinyin (McBride-Chang et al., 2004). In addition, performance on sub-syllabic deletions also showed floor performance for the younger group. The reverse appears to be the case in the older group, where mean performance on the syllable deletions was high. Nonetheless, in these measures and all others, there were significant age effects in the direction expected, with the older children significantly outperforming the younger children on each measure (ps < .001).

Table 2.

Performance on reading-related measures by younger and older Mandarin-speaking children.

| Measure | Younger children

|

Older children

|

Younger children vs. older children

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean (SD) | N | Mean (SD) | t test | |

| Pinyin [22]a | 29 | 0.07 (0.26) | 41 | 20.71 (1.58) | t(43)b = −81.86*** |

| Elision total [38] | 30 | 9.67 (6.02) | 41 | 22.34 (7.86) | t(69) = −7.38*** |

| Syllable [18] | 30 | 9.57 (5.91) | 41 | 14.95 (4.25) | t(50)b = −4.25*** |

| Sub-syllabic [6] | 30 | 0.10 (0.40) | 41 | 2.66 (1.64) | t(46)b = −9.62*** |

| Phonemic [14] | 30 | 0.00 (0.00) | 41 | 4.73 (3.32) | t(40)b = −9.11*** |

| Character reading [120] | 26 | 15.23 (13.88) | 35 | 54.60 (25.73) | t(54)b = −7.67*** |

| Vocabulary [32, 64] | 29 | 10.66 (6.07) | 38 | 17.05 (7.75) | t(65) = −3.67*** |

| Nonverbal IQ [14, 68] | 30 | 19.70 (6.52) | 41 | 31.10 (5.64) | t(69) = −7.88*** |

Note. All data are presented as raw scores.

The number of items for each task is presented in brackets. Where the item number differs from the score, we reported as [item number, total points].

Reported t test corrected for unequal variances.

p < .001.

Table 3 displays the nonparametric correlations between the reading and reading-related measures for younger and older children separately. In both groups, phonological awareness (elision) was significantly correlated with reading ability (younger group: r = .42, p < .05; older group: r = .42, p < .05). As expected, vocabulary was correlated with reading and with nonverbal IQ in both samples.

Table 3.

Nonparametric correlations for reading and reading-related measures in Mandarin-speaking children.

| Younger children

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pinyin | Elision | Reading | Vocabulary | Nonverbal IQ | |

| 1. Pinyin | – | −.25 | −.08 | −.20 | .25 |

| 2. Elision | .11 | – | .42* | −.05 | .10 |

| 3. Reading | .10 | .42* | – | .34† | .17 |

| 4. Vocabulary | −.11 | .20 | .37* | – | .41* |

| 5. Nonverbal IQ | .26 | .34* | .37* | .50*** | – |

|

| |||||

| Older children | |||||

Note. Younger children are above the diagonal, and older children are below the diagonal.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .001.

Do Mandarin-speaking children demonstrate phoneme-level awareness?

Table 4 presents children’s performance on the phonological awareness task divided by the level (syllable, onset/rime, or phoneme) and the position (initial, medial, or final) of the deletion. Both groups of children demonstrated syllable-level awareness; however, by and large, only the older children were able to complete the sub-syllabic- and phoneme-level deletions.

Table 4.

Mean performances on the elision task by type of item.

| Younger children | Older children | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Mean (SD) | ||

| Syllable deletion [18] | .53 (.33) | .83 (.24) |

| Initial [8]a | .57 (.35) | .85 (.24) |

| Medial [2] | .15 (.30) | .61 (.43) |

| Final [8] | .60 (.38) | .87 (.24) |

| Sub-syllabic deletion [6] | .02 (.07) | .44 (.27) |

| Onset [3] | .01 (.06) | .38 (.29) |

| Rime [3] | .02 (.08) | .49 (.36) |

| Phoneme deletion [14] | .00 (.00) | .34 (.24) |

| Initial [6] C_G(V)C | .00 (.00) | .52 (.36) |

| Medial [6] CGVX | .00 (.00) | .09 (.22) |

| Final [2] C(G)V_C | .00 (.00) | .56 (.41) |

The number of items for each type of deletion is presented in brackets.

To examine whether there were differences in performance by level (syllable or phoneme) and position of deletion (initial, medial, or final), we conducted a repeated measures analysis of variance4 for each age group. In older children we included Pinyin as a between-participants factor, whereas in younger children we did not include Pinyin as a between-participants factor and we examined differences in only syllable knowledge and not phoneme knowledge (due to floor effects).

In younger children, there was a significant main effect of the position of deletion in the syllable items, F(1, 39) = 41.23, p < .001. Post hoc analyses revealed that younger children did significantly better on the initial and final syllable deletions compared with the medial deletions, (ps < .001), but there was no difference in performance between these two positions.

In older children, there was no effect of Pinyin on children’s performance on the phonological awareness task. However, there was a significant effect of position (initial, medial, or final), F(2, 68) = 23.78, p < .001, and of level (syllable or phoneme), F(1, 34) = 39.72, p < .001, but no significant position by level interaction. Post hoc analyses revealed that older children performed better on syllable-level deletions compared with phoneme-level deletions (p < .001). Furthermore, older children’s performance on the medial deletions was significantly worse than their performance on the initial and final syllable deletions (ps < .001), with no difference between initials and finals.

Which linguistic levels of phonological awareness are most predictive of reading ability?

Table 5 shows partial correlations between single-character reading and the different grain sizes of phonological awareness that were measured. The top left side of the table shows the relationship among syllabic, sub-syllabic, and phonemic awareness after controlling for vocabulary knowledge and nonverbal IQ for younger and older children separately. Overall, syllable deletions were significantly correlated with reading in Mandarin-speaking children in the younger group (r = .49, p < .05) but not in the older group. In contrast, phoneme-level deletions were significantly correlated in the older children (r = .50, p < .01) but not in the young Mandarin speakers (who showed floor effects in phoneme-level deletions). Sub-syllabic deletions (onset/rime deletions) were not correlated with reading in either group (although this may be an artifact of the small number of these items).

Table 5.

Correlations between single-word reading and elision items.

| Controlling for: | Nonverbal IQ and vocabulary

|

Nonverbal IQ, vocabulary, and Pinyin

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Younger children (N = 21) | Older children (N = 28) | Younger children (N = 21) | Older children (N = 28) | |

| Syllable | .49* | .09 | .48* | .05 |

| Sub-syllabic | −.02 | .22 | −.04 | .19 |

| Phonemic | N/A | .50** | N/A | .49** |

| Syllable | ||||

| Initial | .50* | .02 | .49* | −.02 |

| Medial | .50* | .25 | .48* | .22 |

| Final | .39† | .07 | .38† | .04 |

| Sub-syllabic | ||||

| Onset | −.10 | .27 | −.11 | .27 |

| Rime | .04 | .09 | .02 | .05 |

| Phonemic | ||||

| Initial | N/A | .46* | N/A | .44* |

| Medial | N/A | .35† | N/A | .35† |

| Final | N/A | .37* | N/A | .35† |

Note. N/A, performance was at floor.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

To examine these findings more carefully, we examined these relationships by type of deletion (shown in the bottom half of Table 5). Of interest, all three types of syllable-level deletions were significantly correlated with reading in the younger group but not in the older group of Chinese children, and all three types of phoneme-level deletions were significantly correlated with reading in the older group but not in the younger group. However, the correlations between medial and final syllable deletions and character reading for older children became significant when using Spearman’s nonparametric correlation coefficients to address the extremely high levels of performance on the syllable level tasks in the older group.

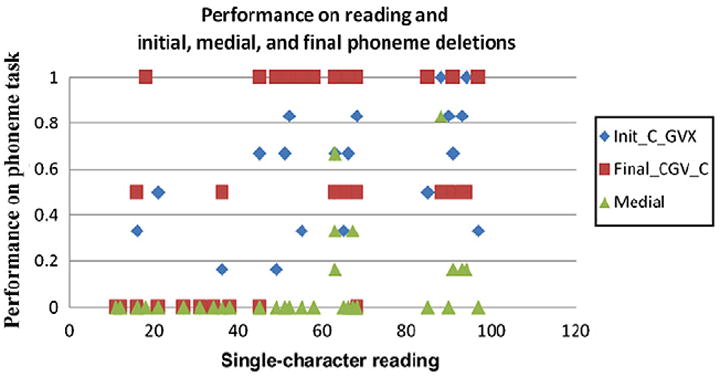

Given the particularly restricted range in performance on the medial phoneme deletions in older children and the importance of these results for testing our hypotheses, we also examined a scatter-plot of the relationship between phoneme-level deletions and reading (Fig. 1). As seen in Fig. 1, there are trends in the relationship with reading for each type of deletion. The clearest pattern can be seen for the initial phonemes, in which there is a clear linear relationship between reading ability and phoneme deletion accuracy. However, for the medial deletions, only children able to identify 60 characters or more demonstrate any ability to complete these types of deletions. Given the skew in these data, we do not include medial deletions as a measure in further analyses, but we return to these findings in the Discussion.

Fig. 1.

Scatterplot of character reading and phoneme deletions.

Does Pinyin knowledge mediate the relationship between phonological awareness and reading in older children?

Given the importance of Pinyin knowledge as a potential mediator of the relationship between phonological awareness and reading, we next conducted two different types of analysis to examine the role of Pinyin training in the relationship between phonological awareness and reading.

The right side of Table 5 shows the correlations between character reading and the deletion type after controlling for vocabulary knowledge, nonverbal IQ, and Pinyin knowledge. Interestingly, there were no major changes in the correlations, although all relationships were slightly attenuated by this additional covariate.

We also conducted a linear regression to examine the contribution of Pinyin knowledge to single-character reading in older children. As shown in Table 6, after controlling for age, vocabulary, and non-verbal IQ, Pinyin was not significantly related to reading ability (β = .14), contributing only 2% of the variance in single-character reading. Furthermore, syllabic and sub-syllabic knowledge also did not uniquely predict reading in older children when entered in the third step (β = .06) and fourth step (β = .23), respectively. In contrast, when phoneme-level awareness was entered in the last step, even after Pinyin knowledge, syllabic, and sub-syllabic awareness, it was a highly significant predictor of reading ability (β = .56, p < .01). When initial and final phoneme deletions were substituted in the final step individually (in two additional regressions), each proved to be a significant predictor of reading ability as well (initial: β = .45, p < .05; final: β = .39, p < .10).

Table 6.

Linear regression equations predicting single-word reading ability: Relative contribution of phoneme-level awareness in explaining reading ability in older children.

| β | t | r2 | Δr2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | .21 | .21* | ||

| Vocabulary | .36 | 1.94† | ||

| Nonverbal IQ | .17 | 0.89 | ||

| Step 2 | .23 | .02 | ||

| Pinyin | .14 | 0.80 | ||

| Step 3 | .23 | .00 | ||

| Syllable awareness | .06 | 0.27 | ||

| Step 4 | .26 | .03 | ||

| Sub-syllabic awareness | .23 | 1.02 | ||

| Step 5 | .44 | .18** | ||

| Phoneme awareness | .56 | 2.81** |

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Discussion

In the current study, we hypothesized that because of the properties of spoken and written Mandarin Chinese, phonological awareness should not be important for learning to read in Chinese when examined at the level of the phoneme. To test this, we examined children’s proficiency at manipulating different levels of phonological information as well as the relationship between this skill and reading outcomes. To our surprise, the results did not support our hypothesis.

The trends in children’s performance on syllable- and phoneme-level deletions were remarkably parallel to those seen typically in English speakers and, more generally, in children learning alphabetic languages. Overall, Chinese children demonstrated an advantage in processing syllable-level phonological information compared with phoneme-level information and demonstrated an advantage for initial and final manipulations relative to medial manipulations, findings with support in the literature on reading in Chinese and in parallel with the literature on reading in English (e.g., McBride-Chang & Kail, 2002; McBride-Chang et al., 2004). Furthermore, preschool-aged Mandarin speakers appeared to be unable to manipulate sounds at the level of the phoneme, a finding consistent with the prevailing view of reading acquisition in Chinese (e.g., Shu et al., 2008). In contrast, when given the opportunity, Chinese first graders in the current sample were able to manipulate sounds at the level of the phoneme. Furthermore, only syllable-level awareness was predictive of reading ability in the younger children, whereas only phoneme-level awareness was predictive of reading ability even after controlling for Pinyin knowledge, vocabulary, syllable, and sub-syllabic awareness in the older children.

These results demonstrate, as others have done before, that phonological awareness is important for explaining individual differences in reading ability in Mandarin-speaking children. However, unlike existing research, the current findings suggest that the nature of the relationship between phonological awareness and reading in Mandarin-speaking children may in fact change over time (Shu et al., 2008) and by first grade phoneme-level awareness is of paramount importance in explaining individual differences in reading ability relative to other phonological grain sizes.

These results raise more questions than they answer. Why, in a language that, by all accounts, provides no phoneme-level insights and requires no phoneme-level insights to facilitate reading acquisition, should phoneme-level awareness be so important in first graders? Furthermore, why does the predictability of the phonological grain size change from preschool to first grade for Chinese readers? Is this simply an artifact of difficulty, or is there a deeper mechanistic explanation? Next we explore possible explanations for these findings and, by extension, answers to these questions.

Why do Chinese children appear to develop phoneme awareness?

Unfortunately, the current study is not longitudinal; thus, we must make comparisons between the younger and older children with caution. However, if we take a speculative foray into explaining what appears to be a developmental shift in phonological awareness, we are drawn to the question of what happens between preschool and first grade that could account for the emergence of phoneme-level awareness in our first-grade sample.

In most European languages, there is a similar developmental shift in children’s awareness from large to small phonological grain sizes (Ziegler & Goswami, 2005). This shift is often explained as a composite of several different factors: (a) alphabetic training, (b) the onset of reading, and (c) task difficulty. No research to date has demonstrated a similar transition from syllable- to phoneme-level awareness in nonalphabetic languages such as Chinese (but see Shu et al., 2008). However, it seems reasonable that a similar triumvirate of explanations could also explain the seeming developmental shift in the current sample of Chinese children.

First, it could be that the phonological training that the older Chinese children received may teach children how to complete phoneme-level awareness tasks (Lin et al., in press). In the teaching of Pinyin, children do have the potential to learn regular grapheme–phoneme correspondences for this Romanized writing system; therefore, it is reasonable to assume that children who have learned Pinyin (i.e., the older children in the current study) understand that words can be segmented into smaller chunks, and this may influence their developing phonological skills. However, although each letter in Pinyin has a corresponding phoneme (or phonemes for letters that have multiple pronunciations; Lin et al., in press), the conventional way of teaching pinyin is generally as onsets and rimes, with units that are presented as bo, po, mo, and fo and as an or ang, and so on, rather than as /b/, /p/, /m/, and /n/ and as /n/ or /ng/, respectively (e.g., Ramsey, 1987). Thus, Pinyin training may provide insight into the process of sound segmentation, but not at the level of the phoneme. Therefore, Pinyin training may influence children’s phoneme-level development only indirectly by giving children a general understanding of segmentation, an understanding that they must then independently extend to the level of the phoneme.

An alternative explanation for the development of phoneme-level awareness in our sample is that the process of learning to read itself refines children’s phonological skills. Similar accounts have been proposed for English-speaking children learning to read (Morais, 2003) and in fact for many European languages as well (e.g., Ziegler & Goswami, 2005). English-speaking preschool-aged children with little or no reading ability demonstrate poor phoneme-level awareness (e.g., Adams, 1990; Bryant, Maclean, & Bradley, 1990; Wagner & Torgesen, 1987), as do adults with no alphabetic training (i.e., illiterate adults) (e.g., Morais, Cary, Alegria, & Bertelson, 1979). Instead, the development of phoneme-level awareness often appears to be coincident with the onset of reading in many alphabetic languages. In fact, researchers have demonstrated a reciprocal relationship between phonological awareness and reading development, particularly for tasks requiring phoneme-level deletions (e.g., Perfetti, Beck, Bell, & Hughes, 1987).

By this logic, it may be that beginning Chinese readers implicitly develop and use the regularity in mapping between syllable (and, to a lesser extent, onset/rime) and characters to aid in reading, and because they use this skill more when first learning to read, there is a concomitant improvement in their phonological awareness skills. Research has shown that beginning Chinese readers use the systematic sound–symbol relations of the characters first learned to bootstrap further character learning/ reading (e.g., Ho & Bryant, 1997b; Shu, Anderson, & Wu, 2000). Better readers appear to be able to detect and capitalize on linguistic/orthographic regularities more effectively than do less skilled readers (e.g., Chan & Siegel, 2001). However, the directionality of this relationship has not been firmly established in Chinese children (e.g., Huang & Hanley, 1997). Is it that children who know more words detect the regularities in new words more easily, or is it that children who are able to detect regularities in new words learn to read more easily?

Interestingly, in the current study, very few children with reading vocabularies smaller than 40 characters were able to complete any of the phoneme-level deletions. Thus, our data suggest that in Chinese readers, there may be a unidirectional influence from reading to phonological awareness, a suggestion that fits with the linguistic properties of Chinese but, unfortunately, cannot be validated given the constraints of our design. However, this explanation fails to answer why developing an understanding of segmentation would focus children’s attention on the level of the phoneme when this is a level not marked by either the orthography or even training in a Romanized representation of the Chinese language. Instead, both explanations (i.e., the influence of reading and the influence of Pinyin training) require that children independently extend their experience with the syllable and onset/rime to the level of the phoneme, a possibility that may prove to be an interesting angle for future research and a distinguishing feature in the development of phonological awareness in Chinese.

A third possibility is that task difficulty may drive the seeming development of phonological awareness in the current sample. It is possible that, “The important question, therefore, is not what type of phonological sensitivity is most important for literacy? but which measures of phonological sensitivity are developmentally appropriate for this particular child?” (Anthony & Lonigan, 2004, p. 53). In the current study, the syllable-level items may have been easy for the older children and the phoneme-level items too hard for the younger children, a possibility that parallels the developmental findings in alphabetic languages. Thus, it is possible what may change with time is that children develop the cognitive resources to process the harder phonological tasks independent of any attribution of phonological development per se.

A final possibility is that we are underestimating the role of phonological information in the linguistic and written properties of Mandarin Chinese. Given the restricted syllable structure of Mandarin Chinese, a single phoneme change (e.g., substituting /m/ with /b/ changes cat [mao1] to bun [bao1]) produces a different word in Chinese, just as it does in English (e.g., cat to bat when /k/ is changed to /b/). As noted, there is evidence that the degree of meaningful phoneme changes in a language may be related to heightened phonological awareness (e.g., Durgunoglu & Oney, 1999).

These are several possibilities, possibilities that may in fact operate in concert, to explain the seeming reversal in performance on the phonological awareness task observed in the current study. However, due to limitations in design, the current study cannot adjudicate among these possibilities. Instead, these results reopen questions about the development of phonological awareness across cultures and highlight important next steps for research on the universality in the development of phonological awareness.

The second question raised by our findings is the following: Why is there a relationship between phoneme-level awareness and reading in Chinese children? In the current study, phoneme-level awareness was uniquely predictive of reading ability in Mandarin-speaking first graders even after controlling for syllable and sub-syllabic awareness. These results underscore a primary question: Why, in a language where there appears to be no systematic or observable relationship between phonemes and characters, should phoneme-level awareness predict reading beyond syllable and onset/ rime awareness?

Similar possibilities to those outlined above exist. Research suggests that Pinyin knowledge can mediate the relationship between phonological awareness and reading in Chinese children (e.g., Huang & Hanley, 1997). However, in the current study, it is not clear why Pinyin training would increase the importance of phoneme-level awareness in predicting reading ability in an orthography where the mapping is not at the level of the phoneme, particularly above other levels (i.e., the onset/rime and the syllable) that do show systematic phono-orthographic mappings in the language (although see Lin et al., in press). An alternative possibility (as stated above) is that we are underestimating the role of phonological information in the spoken and written features of Mandarin Chinese. Just as in English, the spoken properties of Mandarin Chinese may favor phoneme-level processing in a way that is important and meaningful for beginning readers’ comprehension even though it might not be relevant to decoding per se.

A third possibility is that because phonology is universally involved in reading (children must retrieve phonological codes for symbols), phonological awareness may be a unitary construct that relates to reading in all languages at all levels. Accordingly, the linguistic level that shows the strongest relationship with reading is simply the level that shows the greatest variability at the time of testing. Perfetti et al. (2005) pointed out that phonology is a constituent of “word identity” in any language and, thus, phonology is universally involved in word identification. They proposed that cross-linguistic differences in the role of phonology may stem from the timing of phonological information in the word retrieval process but not in whether phonology is involved in word identification/ reading (Perfetti et al., 2005). Thus, because phonology matters, phonological awareness will predict reading acquisition at some point for all languages, and the manifestation of this relationship will depend on developmental factors, such as degree of difficulty, and not on the linguistic properties of the language being learned.

The constraints of the current study do not allow us to identify the particular mechanism underlying the importance of phoneme-level awareness for first-grade readers; however, these findings suggest that the question of how phonological awareness predicts reading is still unresolved. Although there is a growing body of evidence in support of the language-specific hypothesis and one that has paved the way for a new universal model of reading (Goswami, 2008; Ziegler & Goswami, 2005, 2006), we should caution against embracing this approach monolithically. The language-specific theory suggests that given the lack of a direct mapping between phonemes and symbols in Chinese, phoneme-level awareness should not predict reading. Ziegler and Goswami (2005) claimed that “phonological structure, phonological and orthographic neighborhood characteristics, and the transparency of spelling–sound mappings act together to determine the units and mappings that play a role in the amalgamation process in different orthographies” (p. 21). However, our data suggest otherwise. Instead, the results from the current study underscore limits in the ways in which phoneme-level awareness has been measured in studies with Chinese children and point to the important role of phoneme-level awareness even in learning to read a language, which by any account that focuses on the orthographic features of Chinese characters should not structurally require such awareness. Furthermore, the hypotheses we have examined in this section all point to an important clarification in how phonological training may operate and how phoneme-level awareness may emerge in Chinese children. We believe that the results from the current study reopen the question of how phonological awareness is related to reading universally and specifically point to the need for further research on phoneme-level phonological awareness in beginning Chinese readers.

Footnotes

However, it is important to note that there has been growing interest in tone awareness (e.g., Chan & Siegel, 2001; Li, Anderson, Nagy, & Zhang, 2002; Lin et al., in press; McBride-Chang et al., 2008; Shu et al., 2008; So & Siegel, 1997). For the current article, we exclude these studies because it is not clear how to conceptualize tones within the framework of the theory of psycholinguistic grain size (McBride-Chang et al., 2008). It is a topic of debate whether tone should be considered as a separate “phoneme” or whether it should be considered to be a suprasegmental part of the word that is attached to the vowel (Duanmu, 2000; Wang & Cheng, 2008) and, thus, serves to disambiguate homonyms. Furthermore, tones are not explicitly represented in the orthography (except in Pinyin).

This is a transcription of the underlying sounds of the word xian1 using phonetic symbols (Duanmu, 2000). The underlying phonetic transcription differs from the surface transcription in the explicit representation of the glide. The surface phonetic of xian would be represented as /ɕan/ where /ɕ/ represents /si/.

For the target word in this item, the Pinyin is reported in parentheses, the international phonetic alphabet (IPA) symbol is reported for the underlying sounds (versus the surface sounds, Duanmu 2000) in backslash marks, and the correct answer is reported in Pinyin and italics after the equal sign.

Results for all effects in the two repeated measure ANOVAs are reported using the Huynh–Feldt correction for sphericity.

References

- Adams MJ. Beginning to read: Thinking and learning about print. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson R, Li W, Ku Y-M, Shu H, Wu N. Use of partial information in learning to read Chinese characters. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2003;95:52–57. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony JL, Lonigan CJ. The nature of phonological awareness: Converging evidence from four studies of preschool and early grade school children. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2004;96:43–55. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant P, Maclean M, Bradley L. Rhyme, language, and children’s reading. Applied Psycholinguistics. 1990;11:237–252. [Google Scholar]

- Caravolas M, Bruck M. The effect of oral and written language input on children’s phonological awareness: A cross-linguistic study. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 1993;55:1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Chan CK, Siegel LS. Phonological processing in reading Chinese among normally achieving and poor readers. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2001;80:23–43. doi: 10.1006/jecp.2000.2622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Anderson C, Li W, Hao M, Wu X, Shu H. Phonological awareness of bilingual and monolingual Chinese children. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2004;96:142–151. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung H, Chen H-C, Lai CY, Wong OC, Hills M. The development of phonological awareness: Effects of spoken language experience and orthography. Cognition. 2001;81:227–241. doi: 10.1016/s0010-0277(01)00136-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow BW, McBride-Chang C, Burgess S. Phonological processing skills and early reading abilities in Hong Kong Chinese kindergarteners learning to read English as a second language. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2005;97:81–87. [Google Scholar]

- D’Angiulli A, Siegel L, Serra E. The development of reading in English and Italian in bilingual children. Applied Psycholinguistics. 2001;22:479–507. [Google Scholar]

- Duanmu S. The phonology of standard Chinese. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Durgunoglu AY, Oney B. A cross-linguistic comparison of phonological awareness and word recognition. Reading and Writing. 1999;11:281–299. [Google Scholar]

- Goetry V, Urbain S, Morais J, Kolinsky R. Paths to phonemic awareness in Japanese: Evidence from a training study. Applied Psycholinguistics. 2005;26:285–309. [Google Scholar]

- Goswami U. Reading, dyslexia, and the brain. Educational Research. 2008;50:135–148. [Google Scholar]

- Goswami U, Gombert J, de Barrera F. Children’s orthographic representations and linguistic transparency: Nonsense word reading in English, French, and Spanish. Applied Psycholinguistics. 1998;19:19–52. [Google Scholar]

- Ho CS, Bryant P. Development of phonological awareness of Chinese children in Hong Kong. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research. 1997a;26:109–126. doi: 10.1023/a:1025016322316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho CS-H, Bryant P. Learning to read Chinese beyond the logographic phase. Reading Research Quarterly. 1997b;32:276–289. [Google Scholar]

- Holm A, Dodd B. The effect of first written language on the acquisition of English literacy. Cognition. 1996;59:119–147. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(95)00691-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoosain R. Psycholinguistic implications for linguistic relativity: A case study of Chinese. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Hu CF, Catts H. The role of phonological processing in early reading ability: What we can learn from Chinese. Scientific Studies of Reading. 1998;2:55–79. [Google Scholar]

- Huang HS, Hanley JR. Phonological awareness and visual skills in learning to read Chinese and English. Cognition. 1994;54:73–98. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(94)00641-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang HS, Hanley JR. A longitudinal study of phonological awareness, visual skills, and Chinese reading acquisition among first-graders in Taiwan. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 1997;20:249–268. [Google Scholar]

- Katz L, Frost R. The reading process is different for different orthographies: The orthographic depth hypothesis. In: Frost R, Katz L, editors. Orthography, phonology, morphology, and meaning: Advances in psychology. Vol. 94. Oxford, UK: North-Holland; 1992. pp. 67–84. [Google Scholar]

- Leong CK, Cheng P, Tan L. The role of sensitivity to rhymes, phonemes, and tones in reading English and Chinese pseudowords. Reading and Writing. 2005;18:1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Leong CK, Tse SK, Loh KY, Hau KT. Text comprehension in Chinese children: Relative contribution of verbal working memory, pseudoword reading, rapid automatized naming, and onset–rime phonological segmentation. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2008;100:135–149. [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Rao N. Parental influences on Chinese literacy development: A comparison of preschoolers in Beijing, Hong Kong, and Singapore. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2000;24:82–90. [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Shu H, McBride-Chang C, Liu HY, Xue J. Paired associate learning in Chinese children with dyslexia. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology B. 2009;103:135–151. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Anderson R, Nagy W, Zhang H. Facets of metalinguistic awareness that contribute to Chinese literacy. In: Li W, Gaffney JS, Packard JL, editors. Chinese language acquisition: Theoretical and pedagogical issues. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer; 2002. pp. 87–106. [Google Scholar]

- Lin D, McBride-Chang C, Shu S, Zhang Y, Li H, Zhang J, et al. Small wins big: Analytic Pinyin skills promote Chinese word reading. Psychological Science. doi: 10.1177/0956797610375447. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonigan C, Burgess S, Anthony J. Development of emergent literacy and early reading skills in preschool children: Evidence from a latent-variable longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36:596–613. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.36.5.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride-Chang C. Models of speech perception and phonological processing in reading. Child Development. 1996;67:1836–1856. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride-Chang C. Children’s literacy development. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- McBride-Chang C, Bialystok E, Chong K, Li Y. Levels of phonological awareness in three cultures. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2004;89:93–111. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride-Chang C, Cho J, Liu H, Wagner R, Shu H, Zhou A, et al. Changing models across cultures: Associations of phonological awareness and morphological structure awareness with vocabulary and word recognition in second graders from Beijing, Hong Kong, and the United States. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2005;92:140–160. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride-Chang C, Ho CSH. Naming speed and phonological awareness in Chinese children: Relations to reading skills. Journal of Psychology in Chinese Societies. 2000;1(1):93–108. [Google Scholar]

- McBride-Chang C, Ho CS. Predictors of beginning reading in Chinese and English: A 2-year longitudinal study of Chinese kindergartners. Scientific Studies of Reading. 2005;9:117–144. [Google Scholar]

- McBride-Chang C, Kail RV. Cross-cultural similarities in the predictors of reading acquisition. Child Development. 2002;73:1392–1407. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride-Chang C, Tong XL, Shu H, Wong AMY, Leung KW, Tardif T. Syllable, phoneme, and tone: Psycholinguistic units in early Chinese and English word recognition. Scientific Studies of Reading. 2008;12:171–194. [Google Scholar]

- Morais J. Levels of phonological representation in skilled reading and in learning to read. Reading and Writing. 2003;16:123–151. [Google Scholar]

- Morais J, Cary L, Alegria J, Bertelson P. Does awareness of speech as a sequence of phones arrive spontaneously? Cognition. 1979;7:323–331. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison FJ, Smith L, Dow-Ehrensberger M. Education and cognitive development: A natural experiment. Development Psychology. 1995;31:789–799. [Google Scholar]

- National Reading Panel. Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction: Reports of the subgroups. Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Newman EH, Tardif T, Jingyuan H, Shu H. Parallel predictors of reading ability across cultures. University of Michigan; 2010. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Packard JL. The morphology of Chinese. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Perfetti CA, Beck I, Bell LC, Hughes C. Phonemic knowledge and learning to read are reciprocal: A longitudinal study of 1st grade children. Merrill–Palmer Quarterly. 1987;33:283–319. [Google Scholar]

- Perfetti C, Liu Y, Tan LH. The lexical constituency model: Some implications of research on Chinese for general theories of reading. Psychological Review. 2005;112:43–59. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.112.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey SR. The languages of China. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Read C, Zhang Y-F, Nie H-Y, Ding B-Q. The ability to manipulate speech sounds depends on knowing alphabetic writing. Cognition. 1986;24:31–44. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(86)90003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seymour PHK. A theoretical framework for beginning reading in different orthographies. In: Joshi RM, Aaron PG, editors. Handbook of orthography and literacy. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2006. pp. 441–462. [Google Scholar]

- Seymour PH, Aro M, Erskine JM. Foundation literacy acquisition in European orthographies. British Journal of Psychology. 2003;94:143–174. doi: 10.1348/000712603321661859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu H. Chinese writing system and learning to read. International Journal of Psychology. 2003;38:274–285. [Google Scholar]

- Shu H, Anderson RC. Learning to read Chinese: The development of metalinguistic awareness. In: Wang J, Inhoff A, Chen H, editors. Reading Chinese script: A cognitive analysis. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1999. pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Shu H, Anderson RC, Wu NN. Phonetic awareness: Knowledge of orthography–phonology relationships in the character acquisition of Chinese children. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2000;92:56–62. [Google Scholar]

- Shu H, Chen X, Anderson RC, Wu N, Xuan Y. Properties of school Chinese: Implications for learning to read. Child Development. 2003;74:27–47. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu H, McBride-Chang C, Wu S, Liu H. Understanding Chinese developmental dyslexia: Morphological awareness as a core construct. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2006;98:122–133. [Google Scholar]

- Shu H, Peng H, McBride-Chang C. Phonological awareness in young Chinese children. Developmental Science. 2008;11:171–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2007.00654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siok WT, Fletcher P. The role of phonological awareness and visual–orthographic skills in Chinese reading acquisition. Developmental Psychology. 2001;37:886–899. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snow CE, Burns MS, Griffin P. Preventing reading difficulties in young children. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- So D, Siegel LS. Learning to read Chinese: Semantic, syntactic, phonological, and working memory skills in normally achieving and poor Chinese readers. Reading and Writing. 1997;9:1–21. [Google Scholar]