Abstract

Background:

Available evidence shows that only a small proportion of Nigerian women access postnatal care and practice exclusive breastfeeding. Given that both interventions are critical to the survival of both the mother and the new born, it is important to identify factors that militate against an effective postnatal care and exclusive breastfeeding in the country, in order to scale up services. The aim was to determine the major barriers to postnatal care and exclusive breastfeeding among urban women in southeastern Nigeria.

Materials and Methods:

A cross-sectional survey of 400 urban market women using semistructured questionnaires and focus group discussions.

Results:

Out of 400 women interviewed, 365 (91.7%) attended postnatal clinic. Lack of knowledge about postnatal care services (42.2%; n = 14), distant location of the hospitals (36.4%; n = 12) and feeling that postnatal visits was not necessary (21.1%; n = 7) were the main reasons for non-attendance to postnatal clinic. With respect to exclusive breastfeeding, 143 (35.9%) of the women practiced EBF. The main reasons for nonpractice of EBF were that EBF was very stressful (26.2%; n = 67), mother's refusal (23.5%; n = 60), and the feeling that EBF was not necessary (18.1%; n = 46). Thirty five (13.7%) of the women were constrained by time while the husband's refusal accounted for 1.5% (n = 3) of the reasons for nonpractice of exclusive breastfeeding.

Conclusion:

Poor knowledge and inaccessibility to health facilities were the main obstacles to postnatal care while the practice of exclusive breastfeeding was limited by the stress and mothers refusal.

Keywords: Exclusive breastfeeding, postnatal care, southeastern Nigeria, urban women

INTRODUCTION

The postnatal period (or called postpartum, if in reference to the mother only) is defined by the WHO as the period beginning one hour after the delivery of the placenta and continuing until 6 weeks (42 days) after delivery.1 Care during this period is critical to the health and survival of both the mother and the newborn as a large proportion of maternal and neonatal deaths occur during the first 24 hours of delivery. It is estimated that each year, four million infants die within their first month of life, representing nearly 40% of all deaths of children under age the age of 5 with up to one-half of all deaths occurring in the first 24 hours.2 Similarly, more than half a million women die each year as a result of complications from pregnancy and childbirth and two-thirds of these deaths occur in the postnatal period.3 Expectedly, most of these deaths occur in sub-Saharan Africa.

Therefore, the postnatal period presents an ideal time to deliver interventions to reduce maternal and neonatal deaths. Unfortunately, available evidence shows that policies and programs have largely overlooked this critical period, hindering efforts to meet the Millennium Goals (MDGs) for maternal and child survival.4

Early postnatal care visit offers an opportunity to receive information and support for healthy household practices that are key to maternal and child health and survival. These include exclusive breastfeeding, proper nutrition during breastfeeding, counseling on breast care, advice on the care of the newborn, and the use of family planning.

Moreover, in Africa, where there are prevalent noxious practices during the early postnatal period, PNC provides an opportunity to correct the misconceptions sustaining such practices. Within the context of prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV infection, the postnatal clinic also affords the opportunity to assess the women's adherence to postpartum interventions including exclusive replacement feeding, the use of prophylactic ART as well as infant testing for HIV infection.

Although there is not yet a standardized, evidence-based protocol with respect to the essential elements of PNC, the World Health Organization recommends that postnatal care for all newborns should include immediate and exclusive breastfeeding, warming of the infant, hygienic care of the umbilical cord, and timely identification of danger signs such as bleeding and infection with referral and treatment.1 With respect to the timing and number of visits, the WHO recommends postnatal visits within 6-12 hours after birth, 3-6 days, 6 weeks, and at 6 months (6-6-6-6 model).5

A major challenge confronting the effective postnatal care in Africa is that majority of the deliveries occur outside formal health facilities. An analysis of the recent demographic and health Surveys in 23 African countries shows that approximately one-third of women in sub-Saharan Africa deliver in health facilities, and no more than 13% receive a postnatal care visit within 2 days of delivery.6 In Nigeria, only 35% of all births take place in the health facilities.7

Therefore, reaching those women who deliver outside health facilities requires that most PNC services should not only be delivered within the facilities but must be located close to or at home so that the majority of the women will benefit from these services. The need for home delivery of PNC services becomes more compelling when it is considered that in most parts of Africa, cultural, financial, and sometimes geographic barriers limit the ability of the women and their newborns to access early postnatal care.8

Even when services are provided, several factors may interact to deny women and their newborns access to PNC services. These are likely to be those factors that generally limit the ability of women in the developing countries to access to maternal and child health services. These include low maternal education, perception of quality of services, user fees, health care givers attitude, and culturally unacceptable services.9–11

Of all these factors, maternal education seems to be the most significant. For example, in Jordan and Philippines respectively, nonuse of antenatal services declined steadily from 76% and 31% among illiterate women to 59% and 17% among those with elementary education. Among those with Secondary education, it was 30% and 9% respectively.12,13 Similarly in Sagamu, Southwest Nigeria, women with little or no formal education were found more to deliver with the traditional birth attendants.14 This is similar to the report of Nigerian Demographic and Health survey, 2003 that the percentage of births that occur in health facility increases with education, from 10.3% of women with no education to 88.1% among those with higher education.15

Even, among the rural dwellers, utilization of maternal services was positively influenced by maternal education.16

This study investigated the utilization of postnatal care services among Nnewi women of the southeastern Nigeria. The findings will facilitate efforts to scale up postnatal care in the environment.

Nnewi is a semi-urban town located in Anambra state within the southeast region of Nigeria. It comprises four quarters; Otolo, Nnewichi, Uruagu, and Umudim. The town is known for business and technology and has been described as “Japan of Africa.” It has the largest motorcycle and motor spare parts market in Africa. Therefore the inhabitants are predominantly traders and scores of indigenes who are peasant farmers and petty traders. Apart from the central market, each of the quarters has its own daily market that caters for the routine needs of its people. There is electricity and good road network, but no pipe borne water. The residents are mostly Christians with a few Muslims and traditionalists. Due to the presence of a federal teaching hospital, there are a large number of healthcare workers as well as numerous specialist hospitals.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study population comprised market women who had live birth within the past 3 years. Equal numbers (100) of women were selected from each of the four markets, representing the four quarters of the town. Women who withhold consent or who had not delivered a child were excluded from the study.

Data were collected from eligible women using pretested semistructured questionnaires which were either interviewer or self-administered depending on the convenience of the women. The self-administered questionnaires were validated on site. The information obtained included sociodemographic characteristics, knowledge about postnatal care, utilization of postnatal care, the place and timing of postnatal care in the last pregnancy, the reason for the choice and the contents of PNC.

The data were augmented with information from focus group discussions (FGDs) involving selected women. The FGDs consisted of 10–15 participants, a facilitator, tape recorder, and a note- taker. The discussions took place in the evenings between 4.00 pm and 6.00 pm Nigerian time when the women had closed business for the day. The venues were either in a building within the market or under any big tree that provided shade. The language was a mix of the local language (Igbo) and English language as determined by the convenience of the participants. In all, a total of 8 focus group discussions were held – 2 for each of the markets. The parameters used in choosing participants included sociodemographic characteristics likely to affect attitude to the use of postnatal care services.

Data analysis

The collected data were analyzed using EPI INFO version 3.5.1 (2008) software. Descriptive statistics such as means, median, and mode were computed for continuous variables and proportions for nominal characteristics of the women. Pearson's chi-square test was used to assess significance of associations between two nominal variables and a P-value of <0.05 at 95% confidence interval was taken as significant. The results were presented in tables and charts.

Ethical considerations

Ethical clearance was obtained from the ethical committee of the local government area. As much as possible, the rights of patients were protected in this research work and questionnaires were only administered to women who have given their consent, after due counseling.

RESULTS

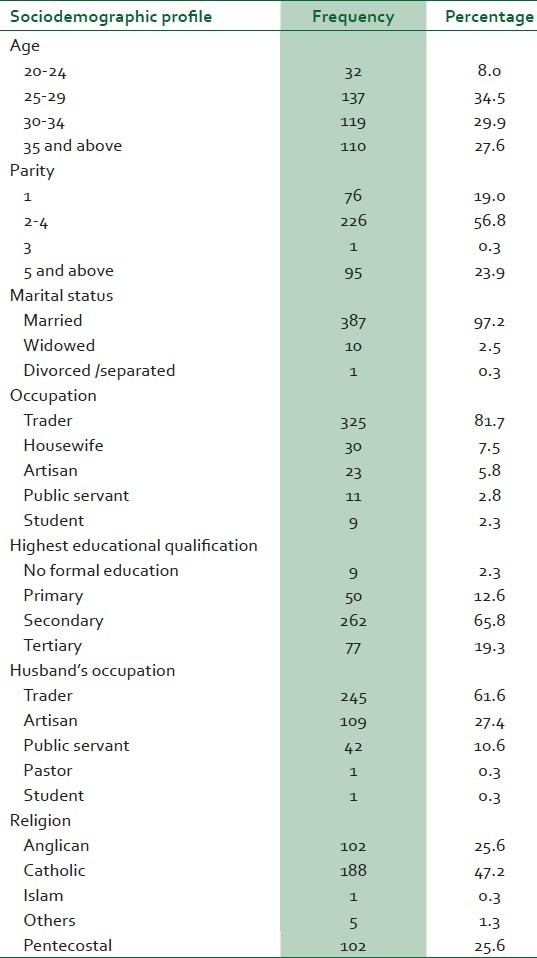

Table 1 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of the respondents. The modal age group was 25-29 (34.2%; n = 136) while the modal parity group was 2-4 (56.8%; n = 226). Literacy level was very high (85.1%; n = 339) and majority of the respondents were traders (81.7%; n = 325). Almost all of the women were Christians (99.7%; n = 397) with a preponderance of the Roman Catholic denomination.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic profile of the respondents

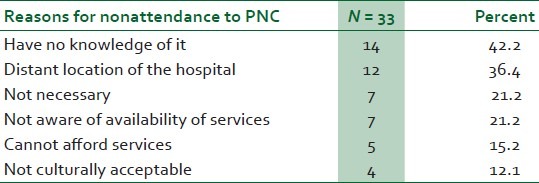

Out of 398 women interviewed, 365 (91.7%) attended postnatal clinic. Lack of knowledge about postnatal care services (42.2%; n = 14), distant location of the hospitals (36.4%; n = 12), and feeling that postnatal visits was not necessary (21.1%; n = 7) were the main reasons for non-attendance to postnatal clinic. This is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Reasons for non-attendance to postnatal clinic

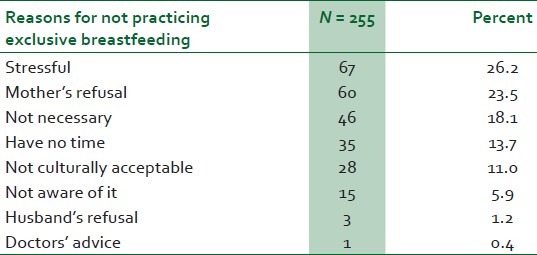

With respect to exclusive breastfeeding (EBF), 143 (35.9%) of the women practiced EBF. The main reasons for nonpractice of EBF were that EBF was very stressful (26.2%; n = 67), mother's refusal (23.5%; n = 60) and the feeling that EBF was not necessary (18.1%; n = 46). This is shown in Table 3. Thirty five (13.7%) of the women were constrained by time and husband's refusal accounted for 1.5% (n = 3) of those who did not do exclusive breastfeeding.

Table 3.

Reasons for not doing exclusive breastfeeding

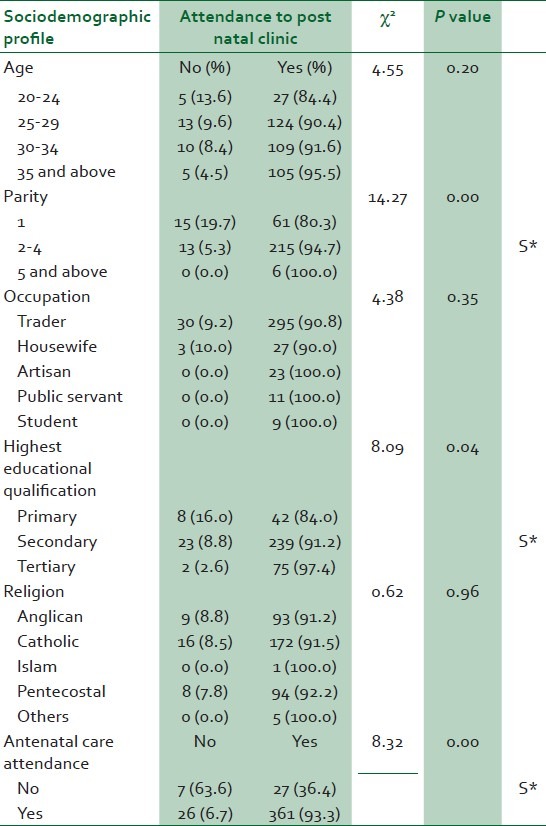

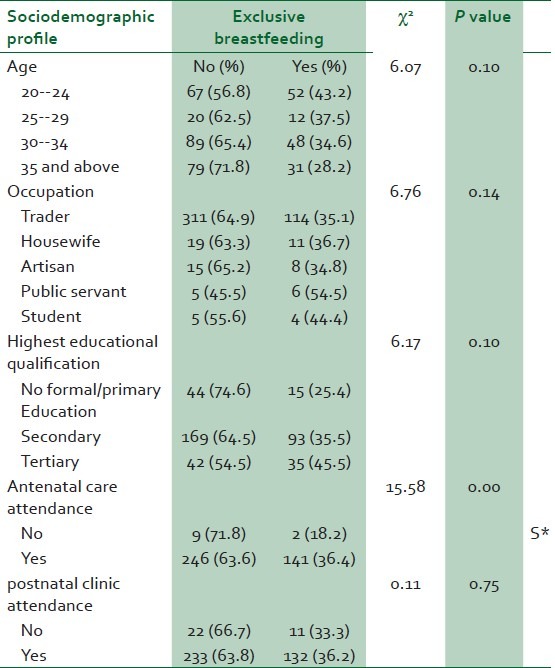

Table 4 shows the influence of sociodemographic factors and attendance to antenatal care to the utilization of postnatal care services. Utilization of postnatal care services was significantly associated with increasing parity (P < 0.01), maternal education(P = 0.04) and attendance to antenatal care(P < 0.01). Although the utilization increases with maternal age, there was no significant association (P = 0.02)Also as shown in Table 5, the practice of exclusive breastfeeding increased with decreasing maternal age (P = 0.10), increasing maternal education(P = 0.10), attendance to both antenatal(P < 0.01) and postnatal clinics(P = 0.75).

Table 4.

Influence of sociodemographic factors on the use of PNC services

Table 5.

Influence of sociodemographic factors on the practice of exclusive breastfeeding

DISCUSSION

Postnatal care practices such as immunization and exclusive breastfeeding are critical to the wellbeing and growth of the baby. For the mother, exclusive breastfeeding within the context of lactational amenorrhea method is an effective postpartum contraceptive method. This method is attractive especially for those women who do not subscribe to artificial methods of family planning.

In the traditional model of maternity care, women are seen at the postnatal clinic 6 weeks after delivery. At this visit, the baby's clinical condition, weight gain, immunization history and neuro-developmental activities are reviewed and recorded. For the mother, questions are asked regarding the return of menstruation, contraception and sexual activities. The uterus is checked for complete involution and further counseling on any relevant matter is completed. After this visit, she is referred to the family planning clinic while the baby is referred to infant welfare clinic for continuation of care. Considering the fact that the first four weeks are critical to the survival of the newborn, this model has been criticized for neglecting this very crucial period in neonatal survival. As a consequence the new model being proposed by the World Health Organization recommends postnatal visit at 1 week postpartum.5

In this study, 91.7% of the women attended postnatal visit after their last delivery. The rate is higher than the national rate7 and may relate to the presence of a Teaching hospital and the attendant high level of sensitization going on in the area with respect to utilization of maternal healthcare services. The major reason for nonattendance for postnatal care were lack of knowledge about postnatal care, followed by the distant location of the health facilities and the feeling that postnatal visit is not necessary.

The above findings underlie the necessity for healthcare givers to emphasize postnatal visits during the antenatal care period and more importantly before discharging the patient after deliveries.

The far location of hospitals as an impediment towards accessing maternal health services has been previously reported in Nigeria. When health facilities are located far away from the people, access to the facility becomes a problem. This is even more relevant in the care of pregnant women who may develop life-threatening complications any time during the course of the pregnancy. Cases where some women in labor had to travel days to reach a facility are still reported in some parts of the country.

Providing universal access to reproductive health for women in the African countries entails provision of adequate facilities as well as good road network and an efficient referral system. Also a significant proportion of the women did not access postnatal care services because they could not afford it. There is no doubt that if maternal health services are made free, most women will access care.

In this study, the likelihood of utilization of postnal care services significantly increased with the parity. This is surprising as women of high parity usually exhibit overconfidence in issues relating to pregnancy and delivery. Therefore, the women of low parity, especially the primigravidae who are usually filled with anxiety and trepidations are expected to utilize the maternal health services more more. The explanation for this interesting finding may lie within the socioeconomic disposition of the two groups being considered. This is seemly so as the study also correlated increased utilization of postnatal care services with increased maternal education. This later finding is not surprising as the positive impact of high maternal educational attainment on utilization of maternal health services has been consistently established.

Another significant finding from the study is the increased utilization of postnatal care services among women that received antenatal care. This underscores the importance of emphasizing antenatal care in the current efforts at reducing the high maternal mortality ratio among the developing countries. It is apparent from this work that in addition to its known benefits, antenatal care also improves the likelihood of utilizing postnatal care services. Therefore, continued effort is required to make quality antenatal care accessible and affordable to the majority of the women in the developing countries.

Both religion and occupation did not significantly influence the utilization of postnatal services.

The practice of exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) was poor among the women as only 35.9% of women did EBF. Exclusive breastfeeding is a critical intervention in improving neonatal and infant's health. In addition to providing adequate nutrition for the baby, it also contain elements that argument the immunity of the baby. Within the context of prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV in the tropical Africa, promotion of exclusive breastfeeding becomes even more crucial. This is because breastfeeding is cultural in Africa and it will take a lot of motivation and boldness for young nursing mother, not to breastfeed her baby, when her relatives and in-laws are present. Moreover, the prevalent poverty and deprivation within the continent makes it difficult for most of the women to afford the replacement feeds.

The major reasons for nonpractice of exclusive breastfeeding include being stressful, mother's refusal and the feeling that EBF is not necessary. There is no doubt that EBF can quite challenging especially for public servants such as bankers and others. This class of women needs additional motivation to be able to exclusively breastfed. If they are made to understand the numerous benefits of exclusive breastfeeding including the contraceptive benefits, it is likely that more of them will accept the strategy.

Also majority of the women did not breastfeed because of their mothers' refusal. This has a big implication for scaling up of EBF as in most Nigerian communities, the mother of the nursing mother stays with her for a variable period of time after delivery to oversee to the welfare of the newborn and the observance of other postpartum traditional practices. In fact, studies have associated the persistence of most these nonbeneficial and often times, harmful practices to the influence of the grand mothers. A lot of community mobilization and sensitization is required in order to carry them along in the current effort at scaling up EBF practices.

The likelihood of practicing EBF increased with maternal education, attendance to both antenatal and postnatal care, and decreased with increasing maternal age. This is the normal trend in utilization of maternal health services. Effort should be intensified during antenatal and postnatal visits in counseling for EBF. Efforts should also be made to address the identified barriers to EBF.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.WHO/RHT/MSM/983. Geneva: WHO; 1998. WHO. Postpartum care of the mother and newborn: a practical guide. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joy E. Washington, DC: Save the Children-U.S; 2006. Lawn analysis based on 38 DHS datasets (2000 to 2004) with 9,022 neonatal deaths, using MEASURE DHS STAT compiler (www.measuredhs.com). Used in: Save the Children-U.S., State of the World's Mothers 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ronsman C, Graham WJ. on behalf of the Lancet Maternal Survival steering group, “Maternal Mortality: Who, When, Where, and Why? Maternal Survival,”. Lancet. 2006;368:1189–200. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69380-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.United Nations: Millennium Development Goals. [Last accessed on 2009 Sep 20]. Available from: http://www.un.org/milleniumgoals .

- 5.World Health Organization, Postpartum Care of the Mother and Newborn: A Practical Guide. 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Warren C. "Postnatal Care," in Opportunities for Africa's Newborns, ed. Joy Lawn and Kate Kerber (Cape Town, South Africa: Partnership for Maternal, Newborn, and Child Health, Save the Children, UNFPA, UNICEF, USAID,WHO, and partners) 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey. National Population Commission and ICF Macro. Calvertom (Maryland) 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Winch PJ, Alam MA, Akther A, Afroz D, Ali NA, Ellis AA, et al. Local Understandings of vulnerability and protection during the neonatal period in Sylhet District, Bangladesh: A qualitative study. Lancet. 2005;366:478–85. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66836-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thaddeus S, Maine D. Columbia University: Prevention of Maternal mortality Program, Center for Population and Family Health; 1990. Too far to walk: Maternal mortality in context. Finings from a multidisciplinary literature review; pp. 56–9. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Starrs A. Report on the Safe Motherhood Technical Consultation. New York: Family Care International; 1998. The Safe Motherhood Action Agenda: Priorities for the next Decade; p. 37. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geneva: WHO; 1999. Reduction of Maternal Mortality: A joint WHO/UNFPA/UNICEF/World bank statement. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abbas AA, Walker GJ. Determinants of the utilization of maternal and child health services in Jordan. Int J Epidemiol. 1986;15:404–7. doi: 10.1093/ije/15.3.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wong EL. Accessibility, quality of care and prenatal care use in the philipines. Soc Sci Med. 1987;24:927–44. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(87)90286-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salako AA, Oloyede OA, Odusoga OL. Factors influencing non-utilization of Maternity care services in Sagamu, South western Nigeria. Trop J Obstet Gynaecol. 2006;23:48–53. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2003. Calverton (Maryland): Macro International; 2003. National Population Commission Federal Republic of Nigeria. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Obuna JA, Umeora OU, Ejikeme BN. Utilization of Maternal health services at the secondary health care level in a limited -resource setting. Trop J Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;24:35–8. [Google Scholar]