Abstract

Background

We previously demonstrated that a general purpose text mining system, the Vaccine adverse event Text Mining (VaeTM) system, could be used to automatically classify reports of an-aphylaxis for post-marketing safety surveillance of vaccines.

Objective

To evaluate the ability of VaeTM to classify reports to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) of possible Guillain-Barré Syndrome (GBS).

Methods

We used VaeTM to extract the key diagnostic features from the text of reports in VAERS. Then, we applied the Brighton Collaboration (BC) case definition for GBS, and an information retrieval strategy (i.e. the vector space model) to quantify the specific information that is included in the key features extracted by VaeTM and compared it with the encoded information that is already stored in VAERS as Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) Preferred Terms (PTs). We also evaluated the contribution of the primary (diagnosis and cause of death) and secondary (second level diagnosis and symptoms) diagnostic VaeTM-based features to the total VaeTM-based information.

Results

MedDRA captured more information and better supported the classification of reports for GBS than VaeTM (AUC: 0.904 vs. 0.777); the lower performance of VaeTM is likely due to the lack of extraction by VaeTM of specific laboratory results that are included in the BC criteria for GBS. On the other hand, the VaeTM-based classification exhibited greater specificity than the MedDRA-based approach (94.96% vs. 87.65%). Most of the VaeTM-based information was contained in the secondary diagnostic features.

Conclusion

For GBS, clinical signs and symptoms alone are not sufficient to match MedDRA coding for purposes of case classification, but are preferred if specificity is the priority.

Keywords: Biosurveillance and case reporting, data repositories, data mining, natural language processing, data access, integration, and analysis

1. Introduction

The Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) is a national passive surveillance system co-managed by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and was created in 1990 to collect safety reports for adverse events following the immunization (AEFI) for vaccines licensed for use in the United States [1]. VAERS helps to identify new and unexpected AEFI and characterize the safety profile of vaccines. These processes are supported by a medical terminology, namely the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA)1 [2]. Following coding conventions and algorithms data-entry personnel apply MedDRA Preferred Terms (PTs) to the text of VAERS reports [3]. The PTs are not considered to be medically confirmed diagnoses but are used in the review process, primarily as search terms for the screening of reports that might be used to identify potential safety signals. Following selection of reports of potential interest using MedDRA terms, medical experts (including internists, pediatricians, and other physicians) at the FDA review the verbatim narratives of reports, synthesize a medical assessment, and organize the information into key features, including diagnosis, cause of death, time to onset, and alternative explanations for the adverse event. Summarizing these features across multiple cases constitutes a ‘case series’ analysis and is critical for signal detection [4]. The first step in case series analysis is case classification. Since MedDRA lacks formal definitions [5], the medical experts classify reports according to the criteria within standardized case definitions, such as the Brighton Collaboration (BC) case definitions [6]. Although MedDRA terminology was not designed to be used as a classification tool, the MedDRA PTs are intended to capture detailed clinical descriptions in the text of the report. We previously showed they can be used for purposes of case classification [7]. Therefore, MedDRA PTs can serve as an appropriate comparator with clinical terms extracted from the text of VAERS reports for the purpose of this analysis.

We have recently developed the Vaccine adverse event Text Mining (VaeTM) system to extract the key features from VAERS reports and support case series analysis [8]. VaeTM is a general purpose tool that automatically tags and organizes the key medical terms after extracting them from the original free text as primary (diagnosis and cause of death) and secondary (second-level diagnosis, rule-out diagnosis, symptoms and treatment) diagnostic, causal assessment (symptom onset time, family and medical history) and quality assessment (vaccine exposures and lot number) features [8]. We evaluated VaeTM’s contribution to the classification of reports of anaphylaxis, by combining the extracted medical terms with an information retrieval algorithm (i.e. the vector space model) and comparing its performance with that of two other classifiers based on the BC case definition of anaphylaxis: a dedicated rule-based ‘text classifier’ [9] and an online classifier (ABC tool) for anaphylaxis [10]. Even though the rule-based ‘text classifier’ performed best [8], further development of dedicated rule-based systems for other case definitions is labor intensive. The general purpose VaeTM system coupled with the information retrieval approach might facilitate the classification of a broader range of conditions.

To further assess this hypothesis, we evaluated the reliability of the extracted features in achieving efficient and accurate classification of reports of Guillain-Barré Syndrome (GBS). We specifically chose GBS for three main reasons: (i) it is an acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy that may cause weakness or paralysis and, because it can lead to respiratory failure, it is potentially fatal or life-threatening; (ii) it is a clinical condition with different characteristics than the previously studied anaphylaxis and a more challenging case classification problem; (iii) it is an AEFI routinely monitored after influenza and other vaccines. To refine our understanding of case classification complexities and the contribution of particular text-mining features, we also quantified the information that is contained within certain VaeTM features.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Data source and report selection

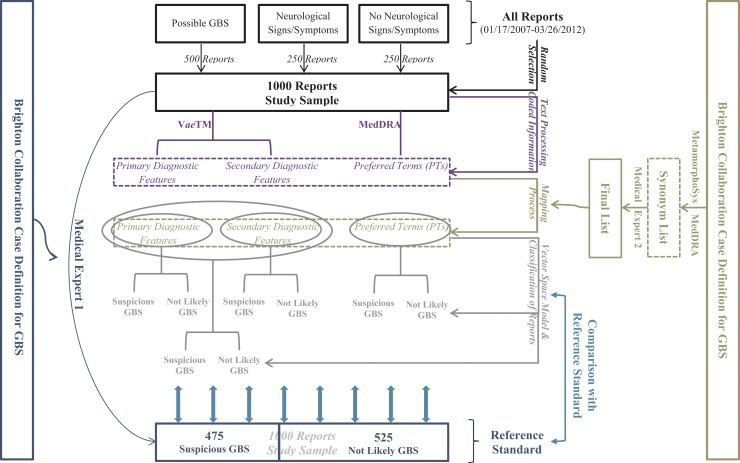

Following the procedure described in detail elsewhere [7], we searched all the reports that were submitted to VAERS from January 17, 2007 to March 26, 2012 (~ 180,000 reports) and identified those that: (i) were likely to be GBS, (ii) included a broad range of neurological signs and symptoms (excluding GBS), and (iii) did not have neurological signs and symptoms. In the group of GBS reports, we included reports with any of the following Preferred Terms (PTs): acute polyneuropathy, chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy, Guillain-Barré syndrome, or Miller Fisher syndrome. In the group of non-GBS neurological events, we included reports with any PT from the System Organ Class of Nervous System Disorders (other than the four GBS terms mentioned above). In the group of non-neurological events, we included reports which did not have any PT relating to GBS or other nervous system disorders. PTs may be listed under more than one System Organ Class. In our medical judgment, some of the PTs with a secondary listing under Nervous System have only marginal neurological relevance (e.g., astrocytoma malignant, which is more usefully classified under Neoplasms Benign, Malignant, and Unspecified; and carotid artery dissection, which is more germanely categorized under Vascular Disorders). However, we decided by consensus to accept the possible limitations resulting from the overlapping categorization. We randomly selected 500, 250 and 250 reports, respectively, from each subgroup to form a sample of 1000 reports that would capture the full range of clinical descriptions of GBS, as well as other neurological and non-neurological conditions that were not likely to be GBS. A physician with many years of experience in pharmaceutical safety surveillance (EJW, one of the co-authors) reviewed and classified them into suspicious (N = 425) vs. not likely (N = 575) to be GBS, using the corresponding BC case definition as a guide (11]. The MedDRA PTs from the same sample were previously used to evaluate MedDRA's ability to support case classification [7]. The selection of reports and the overall methodology are summarized in ►Supplementary Figure 1.

Supplementary Fig. 1.

Summarized illustration of our methodology. The same color was used to highlight all the major subtasks that synthesize each step.

Passive surveillance systems such as VAERS are subject to many limitations, including underreporting, incomplete information in many reports, inadequate data regarding the number of doses administered, and lack of a direct and unbiased comparison group. Because of these and other limitations, it is usually not possible to determine causal associations between vaccines and adverse events from VAERS reports. Indeed, many AEFIs may be purely coincidental.

2.2. Query and information retrieval

To compare the ability to classify reports of features extracted by VaeTM with MedDRA PTs, we followed a 3-step process. First, we created a query of 10 elements that corresponded to the criteria of the BC case definition as those appear in the BC online classifier (ABC tool) for GBS [10]. Each component represented the medical terms and their synonyms that described the key aspects of GBS according to BC case definition; the query was extended by one position to include an element for the actual GBS term. For key medical terms relating to each of the BC criteria and the GBS term, synonyms were identified from the MetamorphoSys Unified Medical Language System (UMLS) browser as well as MedDRA. MetamorphoSys installs one or more of the UMLS knowledge sources and enables user to customize and employ them to maximum advantage for their purposes [12]. It should be noted that no synonyms were found for three criteria: “CSF not collected or results not available”, “CSF total white cell <50 cells/mm3”, “Interval between onset and nadir of weakness between 12h to 28d followed by subsequent clinical plateau”. It is also impossible to retrieve any relevant information for those criteria from either the free text or the MedDRA PTs. One of the authors (RB) reviewed the initial list, deleted inappropriate terms (e.g. neurological terms that did not match any of the GBS criteria) and then mapped each term to the appropriate criterion of the BC case definition. In our previous classification work we created a list using the MedDRA PTs only [7]; here, the information retrieval from the free text mandated the coverage from a larger resource, such as the UMLS.

Second, we compared this query with VaeTM extracted features of all the reports in the GBS set. The primary (DIAGNOSIS and CAUSE_OF_DEATH) and certain secondary diagnostic features (SECOND_LEVEL_DIAGNOSIS and SYMPTOM) matching the medical terms in the query were retrieved; the primary and secondary together comprised the total GBS-related information. Any relevant medical term that either appeared in other feature types (RULE_OUT_DIAGNOSIS or MEDICAL_HISTORY) or was part of a negation in the selected features was excluded from any further processing. The same process was used to query each report and retrieve the appropriate matching MedDRA PTs. Structured Query Language (SQL) statements were used to do the matching between the terms in the initial list and either the VaeTM features or the MedDRA PTs.

Third, we used the cosine similarity of the vector space model (described below) to quantify the amount of the VaeTM- and MedDRA-based GBS-related information that was retrieved in the previous step. This quantification facilitated the comparison of the two systems and the evaluation of VaeTM’s ability to efficiently extract the information of interest. The general approach is described below and exact calculations elsewhere [7;8]. A commonly used spreadsheet tool was used for the vector space model calculations.

2.3. Vector space model

Using the same procedure as in our previous classification studies [7, 8], we represented the above query and reports as vectors. The query vector included 11 components, one for each of the elements described above. The report vectors were of equal length and, practically, each component indicated the matching of either the VaeTM extracted features or the MedDRA PTs in the report with the medical terms in the GBS query representing the BC case definition.

In the vector space model, weighted values were assigned to the vector components in order to generate numerical vectors, which we formulated by applying one of the weighting schemes suggested by the SMART notation [13]. The weight of each component in the query vector was based on either the absolute or the relative frequency of the corresponding criterion in the set of reports and equal to zero when no reports included this criterion. To calculate the absolute and the relative frequency we summed the multiple (i.e. the absolute count) and the single occurrences (i.e. a binary value, 1 or 0), respectively, of each criterion in all the reports of the GBS set. MedDRA PTs do not appear twice in a report, whereas VaeTM extracts a medical term as frequently as the term appears in the narrative; therefore, it was important to distinguish these two types of frequencies. The use of the relative frequency addressed this inequality and allowed a fairer and more consistent comparison of the VaeTM- and MedDRA-based information. At the same time, it was important to investigate whether the actual VaeTM-based was higher than the MedDRA-based information amount in ‘absolute’ terms.

Using the numerical vectors, we calculated the cosine similarity (or score) between the report and the query vectors and, in particular, the VaeTM- and MedDRA-based scores of the reports in the GBS set using both the absolute and the relative frequency of the BC criteria. These scores served as a surrogate for the amount of GBS information in each of the two systems and provided a basis for meaningful comparison. Subsequently, we used the scores to create the probability density and cumulative distribution plots.

2.4. VaeTM feature-based information

The above calculations did not distinguish the primary from the secondary diagnostic features, since MedDRA PTs are not organized into a similar schema. However, after the initial comparison, we evaluated the exact contribution of the primary and secondary diagnostic information to the total VaeTM information that was calculated based on the absolute frequency of the criteria in the GBS set. The primary and secondary diagnostic subscores were used to create two new lines in the same probability density and cumulative distribution plots that illustrated the MedDRA- and the (total) VaeTM-based scores.

We examined the independent contribution of the primary and the secondary diagnostic features to the case classification. For this purpose, the above cosine similarity calculations were repeated separately for the primary and the secondary diagnostic features, ignoring the existence of the supplementary information (secondary and primary, respectively) in each case. Again, the absolute and relative frequencies were used as the basis for the calculations. The new (independent from the total) scores for the primary and secondary diagnostic features, along with the MedDRA- and (total) VaeTM-based scores, were then used to plot the Receiver Operating Characteristics (ROC) curves and calculate the specificity, sensitivity, and area under the curve (AUC) metrics. R statistical environment was used to plot ROC curves and calculate the metrics.

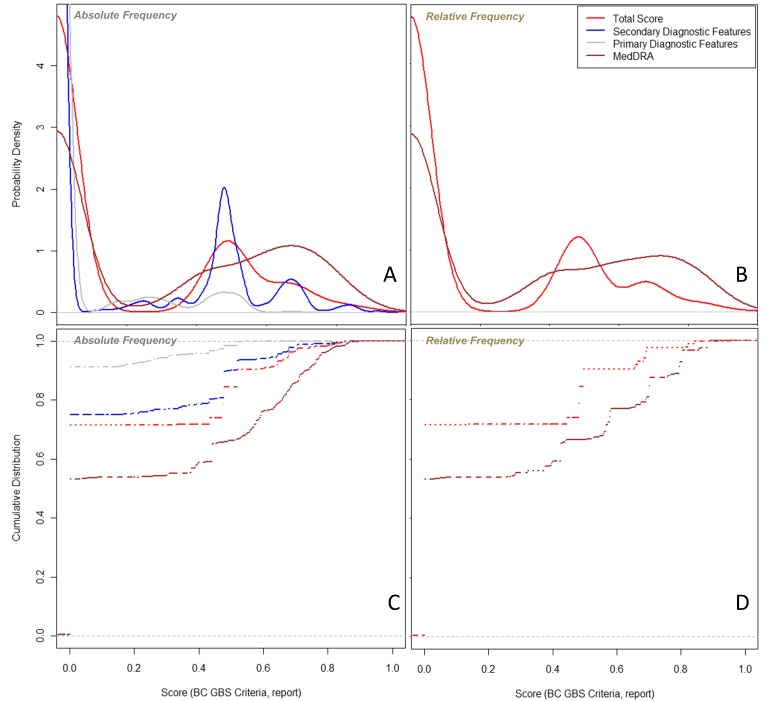

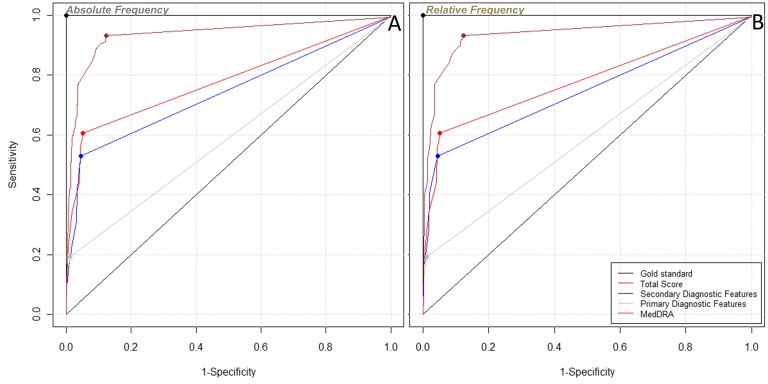

3. Results

The absolute and relative frequencies for the GBS criteria based on either the VaeTM output or the MedDRA PTs are included ► in Supplementary Table 1. In its initial version, VaeTM does not support information retrieval for any lab-related criteria (‘CSF protein level above laboratory normal value’, ‘CSF total white cell <50 cell/mm3’, ‘electrophysiologic findings consistent with GBS’), nor specific temporal information (‘interval between onset and nadir of weakness between 12 h and 28 days AND subsequent clinical plateau’ and the ‘monophasic illness pattern’ criteria). On the other hand, two of the lab-related criteria (‘CSF protein level above laboratory normal value’ and ‘electrophysiologic findings consistent with GBS’) are represented by MedDRA PTs. This additional contribution of MedDRA PTs can be appreciated in the probability density plot and cumulative distribution plot (►Figure 1) for both the absolute and the relative frequencies. Using AUC as the measure for case classification, the MedDRA-based scores surpassed the VaeTM-based scores (absolute frequency-based AUC: 0.904 vs. 0.777, respectively; relative frequency-based AUC: 0.903 vs. 0.777, respectively) (►Table 1). Furthermore, the classification of reports was more sensitive when using the MedDRA-based scores but more specific when using the VaeTM-based scores (►Figure 2). The VaeTM primary-based scores provided even greater specificity than the total VaeTM-based scores. Regardless of whether the absolute or relative frequency was used, the VaeTM-based scores (primary, secondary, and total) did not vary in their contribution to report classification (►Table 1).

Table 1.

Classification of the GBS reports using the absolute and relative frequency-based scores.

| Frequency | Sensitivity [95% CI] | Specificity [95% CI] | AUC3 [95% CI] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute | VaeTM (total)1 | 60.5% [55.8%-65.0%] | 95.0% [92.3%-96.5%] | 0.777 [0.776–0.779] |

| VaeTM (secondary)1 | 52.9% [48.2%-57.6%] | 95.5% [93.5%-96.9%] | 0.742 [0.740–0.744] | |

| VaeTM (primary)1 | 19.3% [15.8%-23.3%] | 98.8% [97.5%-99.4%] | 0.590 [0.587–0.594] | |

| MedDRA2 | 93.2% [90.4%-95.2%] | 87.7% [84.7%-90.1%] | 0.904 [0.904–0.905] | |

| Relative | VaeTM (total)1 | 60.5% [55.8%-65.0%] | 95.0% [92.9%-96. 5%] | 0.777 [0.776–0.779] |

| VaeTM (secondary)1 | 52.9% [48.2%-57.6%] | 95.5% [93.5%-96.9%] | 0.742 [0.740–0.744] | |

| VaeTM (primary)1 | 19.3% [15.8%-23.3%] | 98.8% [97.5%-99.4%] | 0.590 [0.587–0.594] | |

| MedDRA2 | 93.2% [90.4%-95.2%] | 87.5% [84.5%-89.9%] | 0.903 [0.903–0.904] |

1Score calculated using the VaeTM output, i.e. both or either of the primary and secondary diagnostics features

2Score calculated using the MedDRA PTs

3AUC: Area Under the Curve

Fig. 1.

A: Probability density plot for the cosine similarity (score) of the GBS reports based on either the VaeTM features or the MedDRA PTs and the absolute frequency of the Brighton Collaboration (BC) criteria; the total MedDRA-based score is higher than the VaeTM total score. The secondary diagnostic features contribute more to the VaeTM total score than the primary ones. B: Probability density plot for the score of the GBS reports based on either the VaeTM features or the MedDRA PTs and the relative frequency of the BC criteria; as in Figure 1A the amount of MedDRA-based information is higher. In this case there was no separation of the total information between the primary and secondary diagnostic features – only the extraction of a BC criterion per report was counted irrespective of the feature type. C: Cumulative distribution plot for the score of the GBS reports based on either the VaeTM features or the MedDRA PTs and the absolute frequency of the BC criteria; the same observations as in Figure 1A. D: Cumulative distribution plot for the score of the GBS reports based on either the VaeTM features or the MedDRA PTs and the relative frequency of the BC criteria; the same observations as in Figure 1B.

Fig. 2.

A: The Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve for the classification of GBS reports using the MedDRA-and the VaeTM-based scores that incorporated the absolute frequency of the Brighton Collaboration (BC) criteria. B: The ROC curve for the classification of GBS reports using the MedDRA- and the VaeTM-based scores that incorporated the relative frequency of the BC criteria.

4. Discussion

In the current study, we used a standardized case definition for GBS [11] and an information retrieval strategy (i.e., the vector space model) to quantify the corresponding specific information that is included in either the key features extracted by a text mining system (VaeTM) or the MedDRA PTs in VAERS. For report classification, we also evaluated the contribution of the total (VaeTM- and MedDRA-based), as well as the primary and secondary diagnostic feature-based information. MedDRA captured more information and better supported the classification task overall. However, the VaeTM-based classification resulted in better specificity in almost all cases. When specificity approaches 100% the number of true negative reports is maximized and the high specificity guarantees that no GBS cases will be missed in the case series analysis. Low sensitivity means that some reports will have to be manually reviewed that ultimately are not true cases of GBS, so the workload is not reduced ideally. However, the overall process still results in higher efficiency than current manual review while identifying all true GBS cases. Furthermore, most of the VaeTM-based information was extracted under the secondary diagnostic features. MedDRA cannot capture elements for which there are no PTs (e.g., ‘illness pattern, monophasic’); the ability to capture this information might add significant value.

VaeTM was designed without the ability to extract lab-related features because this information is reported relatively uncommonly in VAERS reports so it was thought it would contribute relatively little to case classification. This evaluation of VaeTM’s ability to classify possible reports of GBS illustrates that the inability of VaeTM to extract lab-related features is a major limitation of the system in some circumstances. Confirmation of GBS requires results from diagnostic tests (i.e., CSF protein level and electrophysiologic abnormalities) and since MedDRA contains PTs corresponding to some of these criteria, the comparison of the two approaches highlighted VaeTM’s weakness. Updating the VaeTM system to include lab-related features should improve its utility regarding medical conditions that require the evaluation of lab tests. The inability of both MedDRA and VaeTM to fulfill all the BC criteria, such as ‘illness pattern, monophasic’, points to another limitation of both approaches for classifying GBS. However, such features rarely or never appear in spontaneous reports, and the corresponding information loss is probably insignificant for the classification of reports as “potential” GBS, for the purpose of prioritizing reports requiring expert review.

Current standard data mining strategies are based primarily on medical product-MedDRA PTs pairs [14]. The ability to automatically combine MedDRA PTs or text mining features to classify reports prior to the application of data mining algorithms could offer substantial benefits, such as reduced workload and time savings, if a sufficient number of case definitions are automated. To the best of our knowledge, the most recent studies that dealt with the data mining of spontaneous reporting systems did not incorporate any text mining methods [15-18] and mainly relied on MedDRA terms [19]. The use of text mining strategies has been very limited because of the tools’ limited ability to extract the key information from spontaneous reports [20, 21].

5. Conclusions

By using the BC case definition of GBS to evaluate the adequacy of either the MedDRA-encoded or the VaeTM-extracted textual information for the classification of reports, we evaluated the contribution of the VaeTM primary and secondary diagnostic features to the same task, as well as to the total amount of extracted information. VaeTM extracts the appropriate information in an automated fashion and organizes it into key features; as such, it can supplement traditional post-marketing safety surveillance. The addition of new features to the system (e.g. the ability to extract lab results) would enhance its applicability to case definitions that include lab results. While case classification based on MedDRA performs very well, text mining also affords the possibility of extracting time to onset and alternative explanation features essential for the automation of the case series evaluation. Thus, VaeTM system could offer significant gains in case classification but should be updated to fully contribute to case series analysis.

Clinical Relevance Statement

The use of a general purpose text mining tool (VaeTM) and existing medical terminologies (MedDRA) coupled with general information retrieval algorithm might offer significant gains in post-marketing safety surveillance. The application of automated processes like this could provide reassurance to those submitting reports that individual reports are rapidly screened and appropriately triaged, even in the face of increased numbers of reports. Furthermore, the suggested strategy presented in this study might not only offer significant gains for efficient, rigorous and consistent safety surveillance but also reduce the workload for the medical experts and the overall consumption of resources.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest in the research.

Protection of Human and Animal Subjects

Human and/or animal subjects were not included in the project.

Author contributions

TB conceived the idea, performed the analysis and authored the paper; EJW read adverse event reports and determined the diagnostic level of certainty regarding GBS and edited the manuscript; RB led the overall effort in applying medical informatics to adverse event evaluation, defined the outcomes for the study, selected terms to represent the case definitions and edited the manuscript.

Supplementary Table 1.

Absolute and relative frequencies of the Brighton Collaboration criteria for GBS as identified in either the VaeTM output or the MedDRA PTs.

| Brighton Collaboration GBS criteria | Absolute Frequency | Relative Frequency | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VaeTM | MedDRA | VaeTM | MedDRA | |

| Weakness of limbs, bilateral | 262 | 786 | 131 | 399 |

| Decreased or absent, bilateral deep tendon reflexes | 139 | 282 | 107 | 235 |

| Electrophysiologic findings consistent with GBS | N/A | 310 | N/A | 213 |

| CSF protein level above laboratory normal value | N/A | 323 | N/A | 227 |

| Weakness of limbs, flacid | 141 | 213 | 110 | 158 |

| GBS synonym terms | 70 | 53 | 63 | 53 |

| Identified alternative diagnosis of weakness other than GBS | 9 | 70 | 8 | 64 |

| Illness pattern, monophasic | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| CSF not collected or results not available* | No synonyms | |||

| CSF total white cell <50 cells/mm3* | ||||

| Interval between onset and nadir of weakness between 12h to 28d followed by subsequent clinical plateau* | ||||

*No synonyms were found for those criteria and no related information appeared in either the VaeTM features or the MedDRA Preferred Terms.

N/A: Not Available in either the VaeTM features or the MedDRA Preferred Terms.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported in part by the appointment of Taxiarchis Botsis to the Research Participation Program at the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education through an interagency agreement between the U.S. Department of Energy and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. MedDRA® is a registered trademark owned by the International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations (IFPMA) on behalf of the International Conference on Harmonization (ICH).

Footnotes

1 MedDRA® the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities terminology is the international medical terminology developed under the auspices of the International Conference on Harmonization of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH).

References

- 1.Varricchio F, Iskander J, Destefano F, Ball R, Pless R, Braun MM, Chen RT.Understanding vaccine safety information from the vaccine adverse event reporting system. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 2004; 23(4): 287-294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown EG, Wood L, Wood S.The medical dictionary for regulatory activities (MedDRA). Drug Safety 1999; 20(2): 109-117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown EG.Using MedDRA: implications for risk management. Drug Safety 2004; 27(8):591-602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Food and Drug Administration Guidance for Industry. US Department of Health and Human Services. Available fromhttp://www.fda.gov/downloads/RegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM126834.pdf.Last accessed: 30 October2012

- 5.Bousquet C, Henegar C, Louet ALL, Degoulet P, Jaulent MC.Implementation of automated signal generation in pharmacovigilance using a knowledge-based approach. International Journal of Medical Informatics 2005; 74(7-8): 563-571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonhoeffer J, Kohl K, Chen R, Duclos P, Heijbel H, Heininger U, Jefferson T, Loupi E.The Brighton Collaboration: addressing the need for standardized case definitions of adverse events following immunization (AEFI). Vaccine 2002; 21(3-4): 298-302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Botsis T, Woo EJ, Ball R.Application of Information Retrieval Approaches to Case Classification in the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System. Drug Safety (in press). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Botsis T, Buttolph T, Nguyen MD, Winiecki S, Woo EJ, Ball R.Vaccine adverse event text mining system for extracting features from vaccine safety reports. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 2012; 19(6): 1011-1018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Botsis T, Nguyen MD, Woo EJ, Markatou M, Ball R.Text mining for the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System: medical text classification using informative feature selection. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 2011; 18(5): 631-638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brighton Collaboration ABC tool: Electronic Concultant. Available from: https://brightoncollaborationorg/public/what-we-do/capacity/abc.html Last accessed: 7 July 2012

- 11.Sejvar JJ, Kohl KS, Gidudu J, Amato A, Bakshi N, Baxter R, Burwen DR, Cornblath DR, Cleerbout J, Edwards KM.Guillain-Barré syndrome and Fisher syndrome: case definitions and guidelines for collection, analysis, and presentation of immunization safety data. Vaccine 2011; 29(3): 599-612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.UMLS® Reference Manual [Internet] Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US); 2009Sep. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK9676/

- 13.Manning CD, Raghavan P, Schutze H.Introduction to information retrieval. 1st edition Cambridge University Press; Cambridge; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harpaz R, DuMouchel W, Shah NH, Madigan D, Ryan P, Friedman C.Novel Data-Mining Methodologies for Adverse Drug Event Discovery and Analysis. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics 2012; 91(6): 1010-1021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ali AK, Hartzema AG.Assessing the association between omalizumab and arteriothrombotic events through spontaneous adverse event reporting. Journal of Asthma and Allergy 2012; 5: 1-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harpaz R, Haerian K, Chase HS, Friedman C.Statistical Mining of Potential Drug Interaction Adverse Effects in FDA’s Spontaneous Reporting System. AMIA Annual Symposum Proceedings 2010: 281-285 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kadoyama K, Sakaeda T, Tamon A, Okuno Y.Adverse event profile of tigecycline: data mining of the public version of the u.s. Food and drug administration adverse event reporting system. Biological & Pharmaceutical Bulletin 2012; 35(6): 967-970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trifiro G, Patadia V, Schuemie MJ, Coloma PM, Gini R, Herings R, Hippisley-Cox J, Mazzaglia G, Giaquinto C, Scotti L, et al. EU-ADR healthcare database network vs. spontaneous reporting system database: preliminary comparison of signal detection. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics 2011; 166: 25-30 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pearson RK, Hauben M, Goldsmith DI, Gould AL, Madigan D, O’Hara DJ, Reisinger SJ, Hochberg AM.Influence of the MedDRA hierarchy on pharmacovigilance data mining results. International Journal of Medical Informatics 2009; 78(12): e97-e97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tolentino H, Matters M, Walop W, Law B, Tong W, Liu F, Fontelo P, Kohl K, Payne D.Concept negation in free text components of vaccine safety reports. AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings 2006;1122 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tolentino HD, Matters MD, Walop W, Law B, Tong W, Liu F, Fontelo P, Kohl K, Payne DC.A UMLS-based spell checker for natural language processing in vaccine safety. BMC Medical Informatics & Decision Making 2007; 7: 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]