Abstract

Patients whose skeletal disharmony was severe enough to warrant a surgical treatment option completed a 24-item Motives for Treatment questionnaire. Each item was rated from (1) not at all a reason to (4) very much a reason. Items were grouped to form six dimensions. An average score of 3.0 or greater on a given dimension was considered a strong motivation. Of the 135 patients who completed the questionnaire, 16% of the patients had primarily a self-image motivation, 4% primarily an oral function motivation, and 6% strong dual self-image/oral function motivations. Males and females differed significantly on the social well-being and temporomandibular joint (TMJ) dimensions. A strong social motivation occurred 4.5 times more frequently among males than among females, while a higher proportion of females than males reported TMJ concerns. Patients older than 25 scored higher on oral function, future health, and TMJ dimensions. Patients who elected surgery had higher scores on oral function, nasal function, and TMJ dimensions. Approximately 1.5 times as many patients who elected surgery scored an average of 3.0 or higher on the self-image and oral function dimensions.

In the past decade the number of patients seeking diagnostic evaluation and treatment of dentofacial disharmonies has continued to increase. Given the sociocultural importance of facial appearance and the media’s focus on ways, including orthognathic surgery, to improve appearance, the number of patients seeking treatment for a skeletal disharmony will likely continue to grow. Previous reports from the 1970s and 1980s indicated that patient motivation is a complex interaction of concerns about function, esthetics, future oral health, and social well-being.1–4 However, the motivational profile among patients seeking a diagnostic consultation for a dentofacial disharmony may have changed in the mid-1990s with the increased availability of treatment and social acceptance of orthognathic surgery.5

The purposes of this study were to assess the motivations of a consecutive series of patients who sought diagnostic evaluation at an academic-based care center and were given a surgical treatment option and to compare the motivations of patients, by age, gender, and decision, to accept a surgical treatment plan.

Method and materials

Subjects

Patients seen for a pretreatment consultation in the Dentofacial Deformities Program at the University of North Carolina between January 1, 1993, and June 1, 1996, were eligible to participate if their skeletal disharmony was sufficiently severe to warrant a surgical treatment option. Informed consent was obtained from 155 patients. The sample was predominantly white (83%) and female (61%). The mean age was 26.1 years (range, 13.4 to 54.1 years; SD, 9.8 years). Each subject was contacted at 3 months and then at 6 months after presentation to ascertain the treatment decision (Table 1). By this time, 65% of the subjects had decided to accept the surgical treatment plan, 11 % chose orthodontics only, and 21% chose no treatment. No information regarding treatment decision could be obtained for 5 subjects (3%) who could not be located or did not respond to three messages.

Table 1.

Number of subjects in the age, gender, and treatment decision categories

| Age | Gender | Surgical plan

|

Totals | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accepted | Declined (unknown) | |||

| ≤ 25 yrs | Male | 18 | 11 (4) | |

| Female | 30 | 9 | ||

| Total | 48 | 24 | 72 | |

| > 25 yrs | Male | 15 | 8 (1) | |

| Female | 30 | 9 | ||

| Total | 45 | 18 | 63 | |

| Totals | 93 | 42 | 135 | |

Thirty-three percent of the subjects had previous orthodontic treatment and 10% a previous facial surgery. The primary referral source for these patients was a dental health professional (orthodontist, 40%; dentist, 30%); but 13% were self-referred, and 17% were referred by a friend or family member. Eighty percent had medical insurance.

Instrument

At the initial appointment, prior to being seen by an orthodontist or oral surgeon, each subject completed a Motives for Treatment questionnaire. The Motives for Treatment questionnaire was originally developed by Kiyak et al.3 In 1992, 49 patients who were at least 3 months postpresentation were contacted by telephone and asked about their treatment decision and why they had sought a consultation. From their compiled responses, 11 additional items related to motivation for treatment were added to the original instrument. The revised Motives for Treatment (Table 2) includes 24 possible motives. Each motive is rated using a four-point Likertlike scale from (1) not at all a reason to (4) very much a reason.

Table 2.

Motives for Treatment questionnaire items and the corresponding percentage of patients who rated each item as very much a reason*

| Dimension | Cronbach alpha | % of patients (n = 135) |

|---|---|---|

| Self-image | .84 | |

| Improve appearance of teeth | 57 | |

| Improve facial appearance | 47 | |

| Feel better about self | 38 | |

| Improve general appearance | 29 | |

| Oral function | .75 | |

| Improve the fit of upper and lower teeth | 73 | |

| Improve how front teeth fit together | 58 | |

| Improve how back teeth fit together | 38 | |

| Improve ability to bite into Foods | 36 | |

| Improve ability to chew | 32 | |

| TMJ | .74 | |

| Prevent pain/damage to jaw joint | 40 | |

| Prevent/stop popping or clicking | 25 | |

| Future health | .81 | |

| Prevent tooth loss in future | 38 | |

| Prevent periodontal disease | 24 | |

| Improve general health | 21 | |

| Social well-being | .80 | |

| Increase my confidence | 31 | |

| Improve how I feel about being in public | 14 | |

| Improve ease of interacting socially | 13 | |

| Improve my social life | 12 | |

| Improve work or school performance | 7 | |

| Please my family | 4 | |

| Nasal | .72 | |

| Improve speaking ability | 13 | |

| Improve sinus problems | 7 | |

| Improve ability to breathe | 4 |

Each item is rated from (1) not at all a reason to (4) very much a reason. The scores for items within each dimension are averaged to calculate an overall dimension score.

Responses to the 24-item questionnaire were subjected to an exploratory factor analysis using squared multiple correlations as prior communality estimates. Using the principal factor method followed by a promax (oblique rotation) to extract the factors,6 six factors, each accounting for at least 5% of the common variance, were retained (Table 2). In interpreting the rotated factor pattern, each item in the questionnaire was assigned to a specific dimension, or category, based on the largest factor loading. The six dimensions were labeled oral function, self-image, social well-being, future dental health, TMJ (temporomandibular joint), and nasal function. Scale reliability, assessed by Cronbach’s alpha,7 ranged from .72 to .84 for these six dimensions.

Subjects with incomplete questionnaires (n = 20) were excluded from the analysis. The excluded patients were similar in age and gender to those who completed the questionnaire; only 30% of those excluded accepted the surgical treatment plan.

Data analysis

An average score for each dimension was calculated from the responses chosen for the items belonging to that dimension. Mantel-Haenszel row mean score statistics were used to compare the distribution of Motives dimension scores between males and females, between those 25 years and younger and those over 25 years, and between those who accepted the surgical treatment plan and those who declined surgery. The five subjects whose treatment decision was unknown were excluded from the treatment choice comparison. Subjects with an average motivation score of 3 or greater for a given dimension were categorized as having a strong motivation in that dimension. The proportion of patients with a strong motivation in each dimension was compared between the same groupings using the chi-squared test. Level of significance was set at .05. This level was chosen even with the multiplicity of comparisons because the present study is considered exploratory and hypothesis-generating.

Results

The percentage of patients who chose “very much a reason” for treatment for each of the 24 items on the questionnaire is presented in Table 2. Fifty percent or more of the patients cited the fit of the top and bottom teeth, the fit of the front teeth, and the appearance of the teeth as very important reasons for seeking treatment.

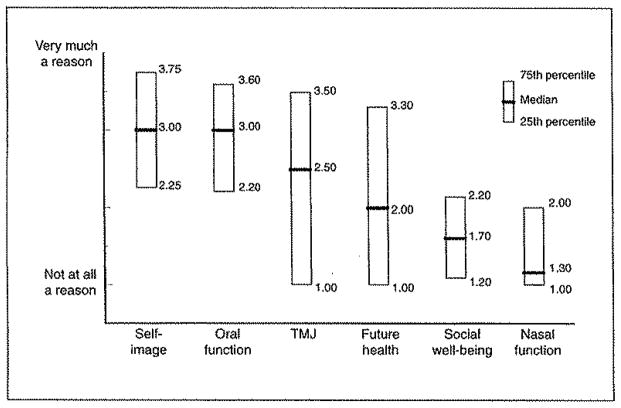

Overall, both self-image and oral function dimensions had median scores of 3.0. Thus, these constructs were strong motivations for 50% of the patients seeking a diagnostic consultation (Fig 1). Sixteen percent of the patients had primarily a self-image motivation for seeking a diagnostic consultation (Table 3); ie, the self-image score was 3.0 or more, but all of the other dimension average scores were less than 3.0. Only 4% had primarily an oral function motivation. Another 17% had strong dual motivations. These patients had dimension scores of 3.0 or greater on two dimensions but not on any other dimension (Table 3). Seventeen percent of the patients did not have an overall strong motivation on any of the dimensions although individual items were rated as “very much a reason.” Of these patients, 56% were female, and 52% accepted the surgical treatment plan. Ninety percent of these patients were referred by a dental health professional.

Fig 1.

Descriptive statistics for the six Motives dimensions for all subjects.

Table 3.

Percentage of subjects with certain patterns of dimensions as motivations for seeking a diagnostic consultation

| No strong* motive dimensions | 17% |

| Single strong dimension | |

| Self-image | 16% |

| Oral function | 4% |

| Dual strong dimensions | |

| Self-image and oral function | 6% |

| Oral function and TMJ | 5% |

| Self-image and TMJ | 6% |

| All dimensions strong | 2% |

Forty-four percent of the patients averaged a score of 3.0 on at least three of the six dimensions.

Strong = an average score of 3.0 or higher calculated from the responses chosen for the items associated with each dimension.

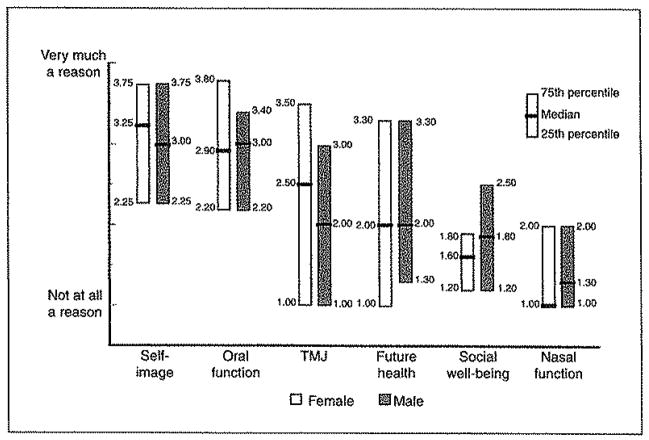

The distribution by gender of the subjects’ dimension scores on the Motives questionnaire are illustrated in Fig 2. No statistically significant differences between males and females were observed for self-image, oral function, nasal function, or future health dimensions. The distribution of scores for social well-being and TMJ dimensions were significantly different for males and females (P = .009 and .03, respectively). Males, on average, had stronger social well-being motivations than did females, while females had stronger TMJ concerns.

Fig 2.

Descriptive statistics for the six Motives dimensions by gender.

Table 4 depicts the proportion of subjects with strong motivations for each dimension by age, gender, and choice of treatment. Although only 18% of the males had a social well-being dimension score of 3.0 or greater, this was 4.5 times the proportion of females. Twenty-six percent of the males cited TMJ concerns while 46% of the females reported such concerns.

Table 4.

Percentage of subjects with a strong* motivation for each dimension

| Agecenter | Gendercenter | Treatment decisioncenter | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤ 25 | >25 | Females | Males | Accepted | Declined | |

| Self-image | 61.0 | 57.1 | 60.3 | 57.9 | 66.7 | 43.2 |

| Oral function | 41.7 | 61.9 | 50.0 | 52.6 | 57.0 | 35.1 |

| TMJ | 27.8 | 49.2 | 46.2 | 26.3 | 43.0 | 24.3 |

| Future health | 27.8 | 47.6 | 38.5 | 35.1 | 43.0 | 24.3 |

| Social well-being | 12.5 | 6.4 | 3.9 | 17.5 | 9.7 | 8.1 |

| Nasal function | 8.3 | 12.7 | 9.0 | 12.0 | 12.9 | 2.7 |

Strong = an average score of 3.0 or higher calculated from the responses chosen for the items associated with each dimension.

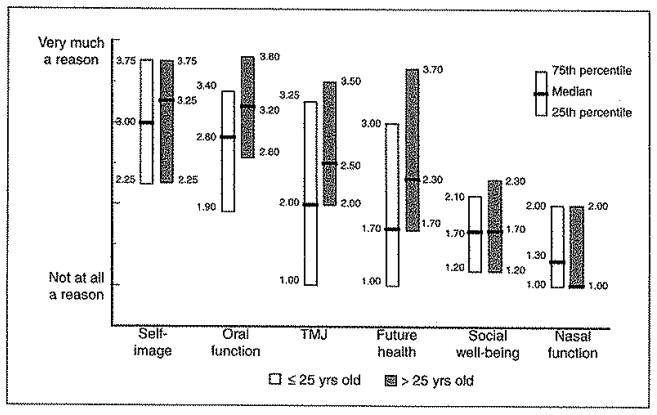

The patients older than 25 years had, on average, statistically significantly different distributions than did the younger patients on the oral function, future health, and TMJ dimensions (P = .001, .008, and .009, respectively) (Fig 3). For all three dimensions, the older patients, on average, had higher scores, and a significantly higher proportion (P = .02, .02, and .01, respectively) had an overall dimension score of 3.0 (see Table 4).

Fig 3.

Descriptive statistics the for the six Motives dimension by age.

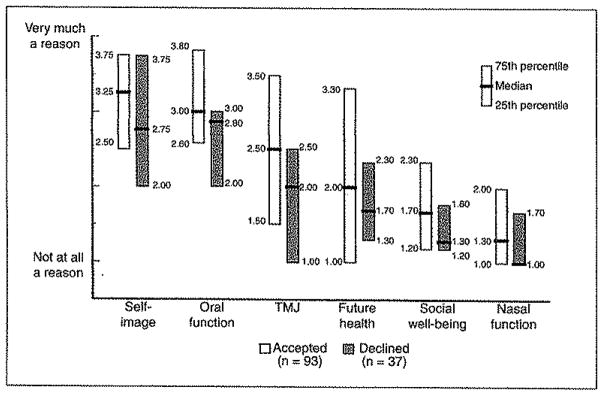

Patients who elected to proceed with the recommended surgical treatment plan within 6 months of the presentation appointment had statistically significantly different distributions with higher scores (Fig 4) on oral function (P = .002), nasal function (P = .03), and TMJ (P = .03) dimensions. Approximately 1.5 times as many patients who elected surgery scored an average of 3.0 on the self-image (P = .02) and oral function (P= .03) dimensions (see Table 4).

Fig 4.

Descriptive the statistics for the six Motives dimensions by treatment decision

Those who elected to proceed with surgery were similar in age and gender to those who did not elect surgery, but a significantly (P = .02) higher proportion (approximately 90%) had medical insurance. Of the 10% who did not have insurance, 75% were male, and 75% scored above 3.0 on the self-image and oral function dimensions. Only 70% of those who did not choose the surgery plan had medical insurance at the time of the initial consultation.

Discussion

Scant current data exist regarding treatment motivations of subjects who seek a diagnostic consultation for dentofacial disharmony. An earlier study of Kiyak et al3 focused on orthognathic surgery patients who were in the midst of the presurgery orthodontic phase. Others reported patient postsurgical recollections of their presurgery motivations2 or data from chart audits.4 Our findings reflect the responses from a self-administered, reliable instrument of a current cohort of patients seeking consultation at an academic center. The lack of standardized, prospective data from different practice settings makes it difficult to assess whether any biases exist in the composition of the patient pool. Although the Dentofacial Program at the University of North Carolina (UNC) draws from the surrounding community as well as the university campus, the majority of these patients were referred by a dental health practitioner. Therefore, even though patients completed Motives for Treatment prior to any contact with UNC staff, the impact of patients’ previous discussions with other health care providers cannot be assessed. It is possible that the motivational profiles in this study sample are different from what would be obtained from patients in their first contact with a dental health professional.

Older and younger patients appear to be equally concerned about appearance and social and interpersonal issues. Older patients, however, were more concerned about functional problems and future health than the younger patients. Such findings are in agreement with developmental theory.

Kiyak et al,3 using a shorter version of the present questionnaire, did not observe any statistically significant differences in the motive patterns between males and females in their study of 74 presurgery patients in the 1970s. Among the present cohort of patients, the distributions for the self-image dimension were quite similar for males and females. However, on average, males rated social well-being more strongly than did females, and a significantly higher proportion of the males had a strong social well-being motivation. Although both males and females desire a change in appearance, it may be that males more than females expect the change in appearance to translate into a social and interpersonal gain. This finding is consistent with the finding that males undergoing rhinoplasty more often believed that surgery would improve career prospects and would aid achievement, while females focused on improved appearance as its own reward.8 Our findings are also consistent with a study of social interaction patterns in college students,9 which found that relative unattractiveness was associated with less male-female socializing among males but not among females.

Although the most frequently reported specific motivation item is related to oral function, the importance of appearance as a motivation for seeking diagnostic evaluation is extremely noteworthy. The median scores on the self-image and oral function dimensions were the same, but a higher percentage of patients had self-image concerns as the single strong motivation factor.

The relative importance of appearance is understandable given the positive attributes associated with attractiveness. As Jacobson10 wrote in 1984, “fairy tale princesses are beautiful, princes and heroes always handsome, where as witches, demons and villains are depicted as bestial, mean and ugly.” Indeed, there is a large and compelling literature suggesting that physical attractiveness is associated with socially desirable qualities and that unattractiveness is associated with undesirable attributes.11–13 The present data suggest that some patients may have internalized the stereotypes associated with unattractiveness, perhaps resulting in the desire for facial change.

Surprisingly, the scores for the socially related motives for treatment were less strong overall than for appearance motives, although there was a moderately strong association between social well-being and self-image (r = .61; P = .0001). This result is puzzling in light of laboratory-based data that suggest that the positive effect of attractiveness is strongest for social competence and interpersonal ease,11 which may lead to a hypothesis that subjects who have a strong desire for an appearance change would also have a strong social motive. However, our finding is consistent with field-based data9,13,14 that suggest a far more complex picture of the effects of attractiveness on social functioning. One review of the attractiveness literature concluded that unattractiveness may primarily be a social handicap in initial interactions and in still photographs but not for long-term relationships.9 Another author14 has suggested that relatively less attractive persons learn valuable interpersonal skills that compensate for their unattractiveness, resulting in satisfying close social relationships. Finally, Bull and Rumsey13 have concluded that no relationship between marital satisfaction and facial attractiveness has been found and that equal numbers of attractive and unattractive individuals form long-term partnerships. It may be that the patients in the present study, overall, do not rate social motives for treatment as highly as appearance motives because they believe that satisfying social relationships are the product of a variety of variables, hence the common wisdom, “looks are only skin deep.” Patients who rate social motives as “very much a reason” for seeking treatment should be carefully questioned and counseled about these motivations.

Although a higher proportion of those who elected to proceed with the surgery plan had medical insurance, many of those who elected no treatment responded “No treatment now … maybe sometime in the future.” Overall, the decision to accept a surgical treatment plan appears to relate to the individual’s internalization of social interactions; cultural, family, and peer values; and the perceived impact on the quality of life. In this study, a larger proportion of those who accepted the surgical treatment plan had strong appearance and/or oral function motivations. This supports Mayo et al’s4 earlier report that patients who believed their disharmony had an effect on their life were more highly motivated for surgery.

Evaluating a patient’s reasons for seeking diagnostic consultation for a dentofacial disharmony is an essential part of an initial interview, and the completion of a standardized, self-administered questionnaire such as Motives for Treatment prior to the patient-parent conference can aid the health professional in several important ways. First, a self-administered questionnaire decreases the likelihood that questions will be phrased differently depending on the clinician’s available time and diagnostic assessment of the patient’s problems. It also decreases the likelihood of a patient responding to an open-ended question in a way that the patient believes the clinician expects or wants. Second, informed consent, as it is now interpreted by bioethicists and the jurisprudence system, requires a dialogue between the health professional and the patient or parent so that the patient becomes a co–decision maker in the treatment decision.15 This patient-practitioner dialogue can be greatly enhanced when the practitioner has clear, uniform information on why the patient is seeking treatment.

A questionnaire like Motives for Treatment can also aid the practitioner in the identification of unrealistic treatment expectations. For example, a patient who rates pain relief as a primary concern may be greatly disappointed if treatment fails to alleviate pain. Thus, a thorough understanding of motives can help practitioners discuss how the treatment options will or will not address the patient’s concerns. Finally, a questionnaire like Motives for Treatment can identify any interdisciplinary consults that may be warranted. For example, a patient whose primary reason for seeking treatment is nasal function might require an otolaryngology consultation, or a patient whose primary motivations relate to social and interpersonal concerns might be referred to a psychologist.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Debora Price and Charlotte Peterson for their help in collecting and analyzing data. This project was supported by NIH DE 10028 and NIH DE 05215.

Contributor Information

Ceib Phillips, Department of Orthodontics, University of North Carolina, School of Dentistry, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

Hillary L. Broder, Division of Behavioral Sciences, University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, Newark, New Jersey.

M. Elizabeth Bennett, Department of Orthodontics, University of North Carolina, School of Dentistry, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

References

- 1.Proffit WR, Phillips C, Dann C., IV Who seeks surgical-orthodontic treatment? Int J Adult Orthod Orthognath Surg. 1990;5:153–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flanary CM, Barnwell GM, Jr, Alexander JM. Patient perceptions of orthognathic surgery. Am J Orthod. 1985;88:137–145. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(85)90238-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kiyak HA, Hohl T, Sherrick P, West RA, McNeill RW, Bucher F. Sex differences in motives for and outcomes of orthognathic surgery. J Oral Surg. 1981;39:757–764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mayo KH, Vig KD, Vig PS, Kowalski CJ. Attitude variables of dentofacial deformity patients: Demographic characteristics and associations. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1991;49:594–602. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(91)90341-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laskin DM. What it takes to make a pretty face [editorial] J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1990;48:1139. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(90)90527-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hatcher L. A step by step approach to using the SAS System for factor analysis and structural equation modeling. Cary NC: SAS Institute; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cronbach U. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychomitrika. 1951;16:297–334. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hay GG. Psychiatric aspects of cosmetic nasal operations. Br J Psychiatry. 1970;116:85–93. doi: 10.1192/bjp.116.530.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reis HT, Hodgins H. Reactions to craniofacial disfigurement: Lessons from the physical attractiveness and stigma literature. In: Eder R, editor. Developmental Perspectives on Craniofacial Disfigurement. New York: Plenum; 1995. pp. 177–201. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacobson A. Psychological aspects of dentofacial esthetics and orthognathic surgery. Angle Orthod. 1984;54:18–35. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1984)054<0018:PAODEA>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eagly AH, Ashmore RD, Makhijani MG, Longo LC. What is beautiful is good, but A meta-analytic review of research on the physical attractiveness stereotype. Psych Bull. 1991;110:109–128. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patzer G. The physical attractiveness phenomena. New York: Plenum; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bull R, Rumsey N. The social psychology of facial appearance. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berscheid E. The question of the importance of physical attractiveness. In: Herman C, Zanna M, Higgins E, editors. Physical Appearance, Stigma, and Social Behavior. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1986. pp. 291–298. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ackerman JL, Proffit WR. Communication in orthodontic treatment planning: Bioethical and informed consent issues. Angle Orthod. 1995;65:253–262. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1995)065<0253:CIOTPB>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]