Abstract

Trichilemmal carcinoma (TC) is a rare cutaneous neoplasm which is derived from adnexal keratinocytes, is histologically invasive, contains cytologically atypical clear cell neoplasm and is in continuity with the epidermis and/or follicular epithelium. However, the diagnostic criteria and even the existence of TC have been contentious. We report the case of a 92-year-old woman with TC of the head and neck region who presented with an unusually long history. She was treated successfully with wide local excision. Important aspects in presentation, differential diagnosis, including histopathological features and management are discussed.

Background

Trichilemmal carcinoma (TC) is a rare, cutaneous adnexal neoplasm that typically occurs in elderly patients on sun-exposed areas of the body.1 It is conventionally considered to be a neoplasm derived from adnexal keratinocytes with glycogenated clear cells and evidence of outer root sheath (ORS) or trichilemmal differentiation, and is the malignant counterpart of trichilemmoma.2–5 The diagnostic criteria for TC have been controversial, however, and even the existence of TC has been the subject of debate.1 5–7

We present a case of this rare lesion with an unusually protracted history.

Case presentation

A 92-year-old woman with a previous history of atrial fibrillation, congestive cardiac failure and a large retrosternal thyroid multinodular goitre with an element of tracheal compression was referred to the head and neck clinic with a large lesion on the right postero-lateral aspect of the skin of her neck (figure 1). The lesion had been present for approximately 12 years but had been treated conservatively because of her general frailty and comorbidities. For 2–3 months preceding referral the lesion had begun to increase in size rapidly, to the extent that neck movement was compromised significantly. There were several small ulcerated areas over the lesion and otherwise on clinical examination there was neither any cervical lymphadenopathy, nor synchronous skin lesions.

Figure 1.

Lesion prepped with Betadine prior to excision.

Investigations

Two fine needle aspiration biopsies were attempted to gain definitive diagnosis but on both occasions were inconclusive. Punch biopsy was performed, therefore, to obtain a histological diagnosis, which was strongly suggestive of TC. Wide local excision was subsequently arranged to confirm tissue diagnosis. During excision 6 mm margins were assessed and taken by the operating surgeon, as a decision was made not to undertake frozen section examination of margins so as to minimise anaesthetic time due to the patient's high anaesthetic risk. The excised specimen (figure 2) was polypoidal with three ulcerated areas on the surface and measured 100×60×60 mm. The resulting defect (figure 3) was closed using a combination of primary closure and a small spilt skin graft.

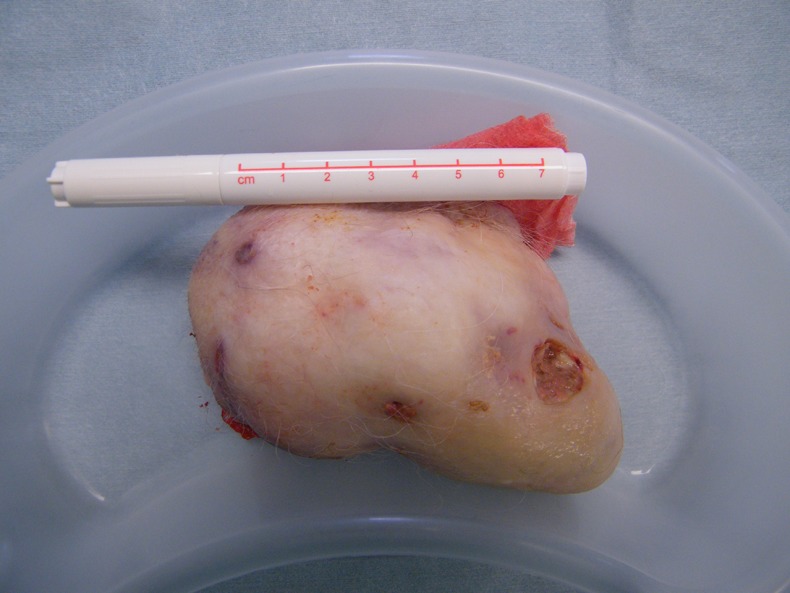

Figure 2.

Polypoidal excised specimen approximately 100×60×60 mm in dimension with several areas of superficial ulceration.

Figure 3.

Resultant defect with manual approximation of wound edges.

Specimen histology revealed extensive involvement of the superficial and deep dermis as well as the subcutaneous tissue with several features supporting a diagnosis of TC—predominantly clear cytoplasm within the tumour cells, moderate nuclear pleomorphism, numerous mitotic figures, abundant foci of trichilemmal type keratinisation, focal peripheral palisading, as well as areas of basement membrane thickening. The tumour reached the deep margin.

Differential diagnosis

TC is typically a solitary indolent lesion that is difficult to differentiate from other skin tumours on clinical grounds alone, and may be mistaken for squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), basal cell carcinoma, nodular melanoma, keratocanthoma or proliferating trichilemmal tumours.8

Histology is, therefore, invariably required to make a definitive diagnosis, although this in itself can be challenging as it is difficult to distinguish TC from clear-cell SCC or Bowen's disease.3

Treatment

Following wide local excision (as described above under investigations), the case was discussed at the regional skin multidisciplinary team meeting. In view of the fact that the deep margin was involved, further local excision was recommended. The patient, however, declined any further treatment.

Outcome and follow-up

At 6 months follow-up the wound had healed well, there were no signs of recurrence and the patient was delighted with her newfound freedom of movement in her neck for the first time in nearly 12 years.

Discussion

TC was first described by Headington9 in 1976 as ‘a histologically invasive, cytologically atypical clear cell neoplasm of adnexal keratinocytes that is in continuity with the epidermis and/or follicular epithelium’, and later during the early 1990s gained attention when several small series were published.1 6 7 TC is the malignant form of trichilemmoma and is distinct from proliferating trichilemmal tumours.2

In Headington's9 10 original description the tumour cells were glycogen rich; showed peripheral palisading; demonstrated a prominent periodic acid–Schiff-reactive and diastase-sensitive basement membrane; and showed trichilemmal keratinisation characterised by absent or minimal granular layer, abrupt single-cell keratinisation and formation of non-lamellar keratin. Headington10 subsequently re-emphasised these features in an invited editorial, but also acknowledged that immunohistochemical characterisation with monoclonal antibodies specific for hair-associated keratins and antigens of the ORS provided additional evidence of trichilemmal differentiation.

The specificity of many of Headington's criteria has been questioned, however, and diagnostic histopathological criteria of TC have varied among several series.1 6 7 Consequently, several investigators have argued that the tumours described by Headington and later reported by others as TC were in fact clear-cell SCCs, which share several histological characteristics of ORS epithelium but are not truly ORS derived.11 To this end, some posited that TC cannot be distinguished from clear-cell SCC with absolute certainty until a specific marker for ORS differentiation is identified, while others have contested the existence of TC altogether.3 5 More recent histopathological studies, however, have confirmed the existence of TC as a distinct entity but have also concluded that its description in the literature may have been overstated, with true TC being even rarer than reports suggest, often being mistaken for other conditions that mimic TC.3 5

TC usually occurs as a solitary lesion on sun-exposed areas, most commonly the head and neck region but also on the trunk or upper limbs.1 2 4 Lesions have typically been present for less than 1 year and exhibit a characteristic accelerated growth phase, prompting medical attention.7 There has been no gender predilection noted but TC typically affects elderly individuals.2 4 Macroscopically, the tumours have been described as exophytic, polypoid or nodular lesions which may be keratotic often with areas of superficial ulceration.1 4 7 9 Accordingly, our case fits with most aspects of this profile. In our patient, however, the lesion had been present for 12 years prior to the characteristic accelerated growth phase, a considerably longer latent phase than is typical and longer than any case reported previously. This supports the indolent nature of TC but also serves to heighten awareness of the variable presentation of the lesion, which may have diagnostic implications.

Interestingly, punch biopsy and surgical excision was required to obtain a histological diagnosis in our case as two fine needle aspiration biopsies were attempted but on both occasions were inconclusive. In a study of the cytological findings of primary palpable skin lesions located on the head and neck Garcia-Rojo et al12 reported cytohistological correlations of 84% and 100% for benign and malignant lesions respectively, with agreement of 100% for trichilemmal cysts. However, no TCs were included in the study. Indeed, there have been no studies investigating the role of fine needle aspiration in diagnosis of TC. Based on our case, fine needle aspiration appears to be unhelpful in the diagnostic work-up of TC with punch or wedge biopsy and surgical excision being required for tissue diagnosis.

Despite its cytologically malignant appearance, TC generally appears to run a non-aggressive course with only local damage and can be treated successfully with surgical excision alone, either wide local excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.1 2 4 6–9 Although there is no published guidance specific to TC regarding surgical margins, practice tends to follow that for cutaneous SCC—namely 4–6 mm margins.13 Accordingly, 6 mm margins were assessed by eye in our case given the size and position of the lesion.

Similarly, there is no published consensus on clinical follow-up for TC after initial treatment. In two of the largest published clinical series of TC neither recurrence nor metastasis was reported after follow-up periods of 11–92 months7 and 2–8 years14 following wide local excision, while Boscaino et al6 reported no recurrence within a 2 month to 4 year follow-up after excision in seven patients. In 1997 Billingsley et al4 reported the first use of Mohs micrographic surgery for TC with no recurrence at 20 months, and more recently Garrett et al2 reported no recurrence at 4 years in two immunocompromised patients following Mohs micrographic surgery. Furthermore, Jo et al15 reported a case where topical immunomodulatory therapy with imiquimod cream was used successfully to treat a histologically confirmed TC with no recurrence after 16 months. Some clinically aggressive examples of possible TC have, however, been reported. Allee et al16 and Kulahci et al17 reported cases of multiple tumour recurrence while Knoeller et al noted a case of lymphatic and skeletal metastasis.18 While these cases may well represent atypically aggressive cases of TC, it again raises questions over histopathological diagnostic accuracy. In view of the relatively small number of reported cases and the varied clinical course, making recommendations on safe follow-up is extremely difficult and decisions need to be made on a case-by-case basis taking account of individual risk. Clearly, in our case it seems prudent to adopt a cautious follow-up approach given the positive deep margin following excision and we intend to follow-up for a minimum of 5 years. Continued efforts to ensure the accurate diagnosis of TC will be important to characterise the precise clinicopathological behaviour of this disease to help guide future follow-up policies.

Learning points.

While atypical, trichilemmal carcinoma (TC) may remain latent for many years before enlarging rapidly and should still be considered in the differential diagnosis of skin lesions presenting as such.

Fine needle aspiration cytology appears unreliable in the diagnosis of TC, with histopathological examination of a tissue biopsy being required for a definitive diagnosis.

In view of the controversy surrounding the histopathological criteria for TC, diagnosis should be restricted to cases in which the majority of morphological findings are present and there is immunohistochemical corroboration to help characterise the precise clinicopathological behaviour of this disease.

TC typically runs a non-aggressive course and can be treated successfully with surgical excision alone, either wide local excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.

In view of the relatively small number of reported cases and the varied clinical course, making recommendations on safe follow-up is extremely difficult and decisions need to be made on a case-by-case basis.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Reis JP, Tellechea O, Cunha MF, et al. Trichilemmal carcinoma: a review of eight cases. J Cutan Pathol 1993;2013:44–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garrett AB, Azmi FH, Ogburia KS. Trichilemmal carcinoma: a rare cutaneous malignancy: a report of two cases. Dermatol Surg 2004;2013:113–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dalton SR, LeBoit PE. Squamous cell carcinoma with clear cells: how often is there evidence of tricholemmal differentiation? Am J Dermatopathol 2008;2013:333–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Billingsley EM, Davidowski TA, Maloney ME. Trichilemmal carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol 1997;2013:107–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Misago N, Toda S, Narisawa Y. Folliculocentric squamous cell carcinoma with tricholemmal differentiation: a reappraisal of tricholemmal carcinoma. Clin Exp Dermatol 2012;2013:484–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boscaino A, Terracciano LM, Donofrio V, et al. Tricholemmal carcinoma: a study of seven cases. J Cutan Pathol 1992;2013:94–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Swanson PE, Marrogi AJ, Williams DJ, et al. Tricholemmal carcinoma: clinicopathologic study of 10 cases. J Cutan Pathol 1992;2013:100–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan KO, Lim IJ, Baladas HG, et al. Multiple tumour presentation of trichilemmal carcinoma. Br J Plast Surg 1999;2013:665–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Headington JT. Tumors of the hair follicle: a review. Am J Pathol 1976;2013:479–514 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Headington JT. Tricholemmal carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol 1992;2013:83–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Misago N, Ackerman AB. New quandary: tricholemmal carcinoma? Dermatopathol Pract Conceptual 1999;2013:463–73 [Google Scholar]

- 12.García-Rojo B, García-Solano J, Sánchez-Sánchez C, et al. On the utility of fine-needle aspiration in the diagnosis of primary scalp lesions. Diagn Cytopathol 2001;2013:104–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gurudutt VV, Genden EM. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. J Skin Cancer 2011;2013:502723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong TY, Suster S. Tricholemmal carcinoma. A clinicopathologic study of 13 cases. Am J Dermatopathol 1994;2013:463–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jo JH, Ko HC, Jang HS, et al. Infiltrative trichilemmal carcinoma treated with 5% imiquimod cream. Dermatol Surg 2005;2013:973–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Allee JE, Cotsarelis G, Solky B, et al. Multiply recurrent trichilemmal carcinoma with perineural invasion and cytokeratin 17 positivity. Dermatol Surg 2003;2013:886–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kulahci Y, Oksuz S, Kucukodaci Z, et al. Multiple recurrence of trichilemmal carcinoma of the scalp in a young adult. Dermatol Surg 2010;2013:551–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knoeller SM, Haag M, Adler CP, et al. Skeletal metastasis in tricholemmal carcinoma. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2004;2013:213–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]