Abstract

Paraneoplastic neurological disorders are relatively rare conditions posing both diagnostic as well as therapeutic challenges. A previously fit 66-year-old woman presented with subtle cerebellar symptoms which progressed rapidly over the course of days. Chest x-ray and routine blood tests were unremarkable. CT of the head with contrast showed no abnormality. Lumbar puncture showed no evidence of infection or oligoclonal bands. She was transferred to a neurological centre from a remote and rural setting. Subsequent MRI was reported to be normal as well. Tumour markers were negative but the paraneoplastic anti-Yo antibody was positive. A whole body CT scan revealed a spiculated left breast lesion which turned out to be malignant on fine needle aspiration. She underwent left mastectomy, had plasmapharesis and received high-dose intravenous Ig for her paraneoplastic neurological symptoms. She remained neurologically stable and underwent rehabilitation in her local hospital before getting discharged home.

Background

Neurological manifestations of a cancer are common and often disabling. Paraneoplastic neurological disorders (PNDs) are much less common than the direct, metastatic or treatment-related complications of a cancer. Nevertheless, they are important because they cause severe neurological morbidity and mortality and frequently present to a neurologist or a physician without a known malignancy. They are often a diagnostic as well as a management challenge. There are always increased risks of misdiagnosing these cases as something else, such as, cerebrovascular disease, labyrinthitis, etc if careful thought is not given. At the same time, owing to the relative rarity of PND, neurological dysfunction should only be regarded as paraneoplastic after explicitly ruling out other conditions. This case presented in a remote and rural hospital. After preliminary investigations, she was referred to a specialist centre for further investigations and management, with PND as one of the differential diagnoses.

Case presentation

A 66-year-old woman presented with a 3-day history of sudden onset of unsteadiness with walking, and slurring of speech which worsened rapidly. Initially, she noticed herself to be staggering to the right and felt her speech to be slurred and thick. Soon she felt her walking was ‘all over the place’ as if she was ‘drunk’. There were no other neurological symptoms reported and systemic enquiry was unremarkable. She had a history of hypertension for which she had been on indapamide modified release 1.5 mg once daily; she was also taking omeprazole 20 mg daily for dyspeptic symptoms. She did not smoke but drank a glass of red wine with her evening meals. There was no relevant family history of any neurological disorder.

On examination, she looked well and had normal mental status. Her vital signs, including respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, temperature, blood pressure and pulse rate, were within normal range. Neurological examination revealed bilateral finger–nose ataxia, dysdiadochokinesia, bilateral heel-shin ataxia and a slightly broad-based ataxic gait. She also had mildly slurred speech. There was no nystagmus, motor weakness or sensory disturbance and the cranial nerves were intact. Other system examinations were unremarkable.

Investigations

Her routine blood tests were within normal range and tumour markers were negative.

ECG, chest x-ray and CT scan of the brain were unremarkable. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination results were within normal range. Apart from an elevated protein level at 0.94 g/l (0.2–0.4 g/l), there was no oligoclonal band detected.

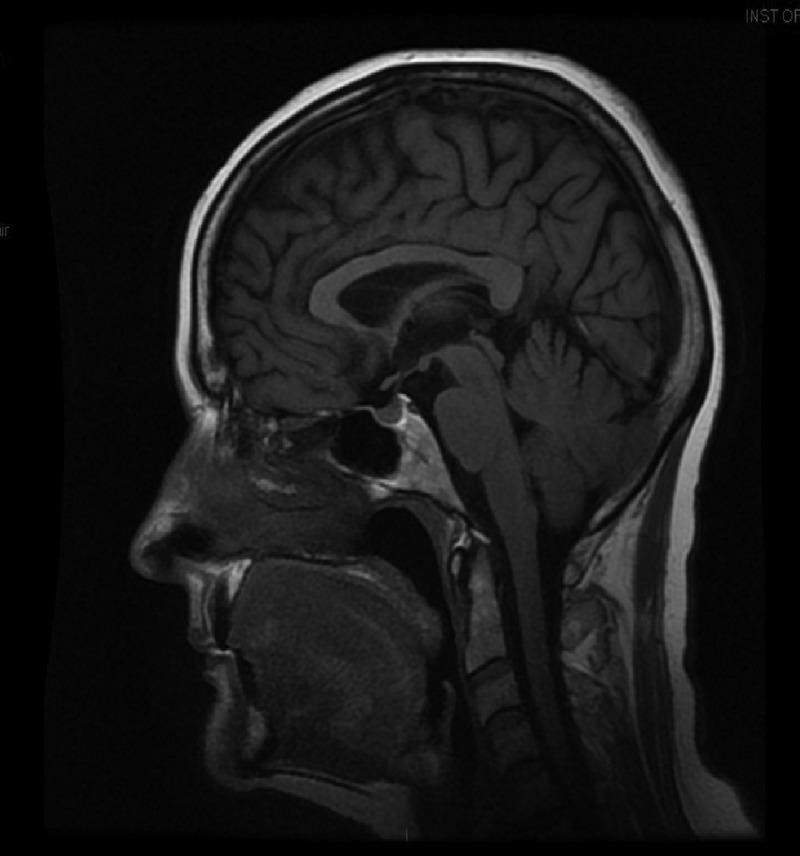

MRI of the brain and cervical spine (figure 1) did not reveal any lesions or demyelination and was reported as normal. A whole body CT scan showed a 19 mm spiculated-enhancing lesion in her left breast, but there was no evidence of metastatic disease. She subsequently underwent a mammogram (figure 2A,B) and an ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration. The histopathology result confirmed the lesion to be a triple negative (oestrogen receptor, progesterone receptor and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)), moderately differentiated ductal carcinoma of the breast. Her further CSF test results for antineuronal antibodies came back positive for an anti-Yo antibody (anti-Purkinje cell antibody 1) at titres 1:640.

Figure 1.

MRI of the brain and cervical spine did not reveal any lesions or demyelination.

Figure 2.

(A) Mammogram, (B) mammogram—magnified view.

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnosis of her subacute presentation of cerebellar manifestations initially included multiple sclerosis and posterior circulation stroke, possibly due to a vertebral artery dissection causing bilateral cerebellar infarcts, a space-occupying lesion in the posterior fossa, PNDs, toxins including alcohol and prion disease. The CSF findings and MRI of the brain and cervical spine excluded the possibility of demyelinating disease. Also, the MRI of the brain did not show any cerebrovascular abnormality or any space-occupying lesion. Alcohol and toxins were excluded by history and examination.

The differentials were then narrowed to PND or prion disease. But the paraneoplastic anti-Yo antibodies were positive, confirming the diagnosis of PND and pointing strongly to paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration (PCD). The whole body CT scan confirmed the presence of a breast lesion. The initial physical examination was unrevealing for ovarian mass or breast lesion, and thus a whole body CT scan was arranged. Subsequently, a histopathological examination confirmed the breast lesion to be a moderately differentiated triple negative (oestrogen receptor, progesterone receptor and HER2) ductal carcinoma of the breast, which was obviously the cause of her PND (PCD in particular).

Treatment

She underwent left mastectomy with axillary clearance; the lymph nodes showed no evidence of local invasion, but unfortunately she was not fit enough for adjuvant chemo-radiation. She had five courses of plasma exchange and was also given high-dose intravenous Ig 0.4 g/kg for 5 consecutive days within 3 weeks of onset of her neurological symptoms. By this time, there was gross deterioration in her neurological condition with marked cerebellar ataxia with inability to sit out in the chair and gross disturbance of speech with typical ‘staccato’ quality. However, she remained stable over the next few weeks and her condition appeared to have reached a plateau. She was transferred back to her local hospital where she underwent multidisciplinary rehabilitation with small improvements in her functional abilities. The psychological impact of the disease had been no lesser than the physical impact. She was very emotionally labile and had shown signs of depression for which she received psychiatric input.

Outcome and follow-up

The primary tumour responsible for this woman's PND became obvious on whole body CT examination during the course of extensive investigations. She underwent surgical removal of the breast tumour along with plasma exchange and high-dose Ig therapy. Her condition plateaued and there was no further neurological deterioration.

The patient showed very slow functional improvement with rehabilitation in the local hospital. She was able to sit on a supported chair and was also able to feed herself with some help. She stood up with the help of two persons and took a few steps with the help of one and a Zimmer frame. Her speech remained very slurred; she was cognitively sound but emotionally labile. Her progress plateaued after 12 weeks of therapy and she was discharged home with a care package and with her husband's support.

Discussion

Neurological manifestations of cancer are common and are often disabling. PNDs are much less common than the direct, metastatic and treatment-related complications of cancer, but are nevertheless important because they cause severe neurological morbidity and mortality and frequently present without a known malignancy.1

PNDs are strongly believed to be immune-mediated and the main targets of the immune responses are neurons and peripheral nerves, although any part of the central, peripheral or autonomic nervous system, including the retina and muscle, can be involved.2

There are several forms of PNDs described in the literature—those affecting the central nervous system include paraneoplastic encephalomyelitis/sensory neuronopathy, PCD, paraneoplastic opsoclonus–myoclonus, paraneoplastic retinal degeneration, acute necrotising myelopathy, stiff person syndrome and motor neurone syndromes. Also, PNDs affecting the peripheral nervous system like dorsal root ganglionitis, Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome (LEMS), myasthenia gravis and polymyositis/dermatomyositis are described. Our case was that of PCD.

Not many studies have been carried out regarding the prevalence and incidence of PNDs. In one study, they found that 4% of women with breast cancer, 16% of men with lung cancer and 6.6% of patients with all cancers had evidence of a PND compared with 1–2% of age-matched controls,3 whereas other studies have shown the incidence to be less than 0.1%.1 LEMS is thought to be the commonest form of PND occurring in about 1% of patients with cancer.4

A finding of specific antineuronal antibodies in these cases of PNDs can be of great help and lead to an early and specific diagnosis, while other investigations are usually negative or non-specific.5 Although the presence of an antineuronal antibody has been described, it is an uncommon finding in PCD owing to breast carcinoma.6 Paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration usually progresses rapidly within days or even hours to affect all limbs and the trunk, resulting in severe disability. As in our case, the neurological manifestations progressed within days from the onset. The most commonly associated tumours are small cell lung cancer, breast and ovarian cancer and Hodgkin's lymphoma.7 The first goal of therapy for PNDs is the treatment of primary tumour because this tends to offer the best chance for neurological stabilisation or improvement.8 9 Treatment of PCD is often unsuccessful, although there are reports of improvement with tumour treatment and immunotherapy if patients are treated while symptoms are still progressing.10 11

Learning points.

Paraneoplastic neurological disorders (PNDs) are relatively rare and pose a diagnostic as well as a therapeutic challenge.

One should have a high index of suspicion for diagnosis.

Once an acute or a subacute cerebellar syndrome has been recognised and a structural lesion in the cerebellum (eg, a tumour and a demyelinating disease) has been excluded, the differential diagnosis is limited to, for example, prion diseases, toxins (including alcohol) or paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration.

Identification and treatment of tumour causing PND offer the best chance for neurological stabilisation or improvement.

PNDs respond better to plasmapharesis or intravenous Ig if the treatment is started early while the symptoms are still progressing.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Rees JH. Paraneoplastic syndromes: when to suspect, how to confirm, and how to manage. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2004;2013(Suppl II):ii43–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bataller L, Dalmau JO. Paraneoplastic disorders of the central nervous system: update on diagnostic criteria and treatment. Semin Neurol 2004;2013:461–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Croft P, Wilkinson M. The incidence of carcinomatous neuromyopathy in patients with various types of carcinomas. Brain 1965;2013:427–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Honnorat J, Antoine JC. Paraneoplastic neurological syndromes. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2007;2013:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moll JWB, Henzen-Logmans SC, Splinter TAW, et al. Diagnostic value of anti-neuronal antibodies for paraneoplastic disorders of the nervous system. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1990;2013:940–3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderson NE, Rosenblum MK, Posner JB. Paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration: clinical-immunological correlations. Ann Neurol 1988;2013:559–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shams'ili S, Grefkens J, De Leeuw B, et al. Paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration associated with antineuronal antibodies: analysis of 50 patients. Brain 2003;2013:1409–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graus F, Keime-Guibert F, Rene R, et al. Anti-Hu associated paraneoplastic encephalomyelitis: analysis of 200 patients. Brain 2001;2013:1138–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vedeler CA, Antoine JC, Giometto B, et al. Management of paraneoplastic neurological syndromes: report of an EFNS task force. Eur J Neurol 2006;2013:682–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blaes F, Strittmatter M, Merkelbach S, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulins in the therapy of paraneoplastic neurological disorders. J Neurol 1999;2013:299–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.David YB, Warner E, Levitan M, et al. Autoimmune paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration in ovarian carcinoma patients treated with plasmapheresis and immunoglobulin. A case report. Cancer 1996;2013:2153–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]