Abstract

Oncology nurses are experts in pain management, and pain is the hallmark of sickle cell disease (SCD). Because individuals with cancer and individuals with SCD often receive care from hematologists or oncologists and are admitted to the same nursing units, oncology nurses need to have an understanding of SCD and the challenges that these individuals face.

Oncology nurses most often care for patients who are admitted for oncologic or malignant hematologic disorders. As a result of the disorder and treatment, pain is a significant symptom for many of these patients. Oncology nurses are experts in pain assessment and pain management. For that reason, other populations that experience pain as a significant symptom of their disease may benefit from the pain management skills of oncology nurses. One such population is individuals with sickle cell disease (SCD), a noncancerous hematologic disorder.

Pain is the hallmark symptom of SCD. Individuals with cancer and those living with SCD often receive care from hematologists and oncologists and may be admitted to the same unit. Therefore, oncology nurses need to have an understanding of the care of individuals with SCD and the challenges they face with a chronic disease. The purposes of this article are to provide a brief overview of SCD, compare the pain of SCD and cancer, and provide suggestions on the role oncology nurses can have in the management of hospitalized individuals with SCD.

Overview of Sickle Cell Disease

SCD refers to a group of inherited conditions in which a gene mutation causes the hemoglobin to assume a sickle shape, promoting vaso-occlusion and leading to both acute and chronic vascular inflammation (Ballas et al., 2012). The hallmark of the disease is pain caused by vaso-occlusion, reperfusion injury, and hypoxemia (Rees, Williams, & Gladwin, 2010). SCD affects about 1 in 500 African Americans and Hassell (2010) noted a U.S. SCD population estimate of 72,000–98,000 when corrected for early mortality. As a result of newborn screening, prophylactic penicillin treatment in childhood, and other aggressive treatments for pain and disease complications, Platt et al. (1994) reported that the median age of death was 42 years for males with homozygous HbSS disease or SCD-SS and 48 years for females with SCD-SS, whereas in individuals with heterozygous or SCD-SC, the median ages of death were 60 and 68 years for males and females, respectively. Although advances have been made in the diagnosis and treatment of SCD, it remains a difficult, chronic medical condition with acute painful exacerbations. Mousa et al. (2010) noted that an acute painful crisis is characterized by a sudden onset of pain that might start in any part of the body, including the back, long bones, and chest; the pain ranges from mild to severe or even excruciating and has been described as deep, gnawing, and throbbing.

Pain episodes or crises can last hours or days, and individuals with SCD may have episodes once or many times a year. In a study of 232 individuals with SCD aged 16 years and older, Smith et al. (2008) found that pain was reported on about 55% of 31,017 analyzed diary days, and about 29% of the patients reported pain on more than 95% of these days; only 14% reported pain on 5% or fewer days. Smith, Jordan, and Hassell (2011) concluded that in adults with SCD, pain often is the rule rather than the exception, and is far more prevalent and severe than previous studies have suggested.

Transition in the Delivery of Care

Introduced in 1996, hospitalists are physicians, nurse practitioners, or physician assistants who specialize in delivering comprehensive medical care to hospitalized patients and have become one of the dominant groups of healthcare providers of inpatient care in North American hospitals (Kuo & Goodwin, 2011). Patients who are defined as unattached or who have primary physicians who do not provide inpatient services are transferred to the care of a hospitalist on admission. Smith et al. (2011) reported that hospitalists are increasingly more likely to manage inpatient admissions of adults with SCD. Hospitalists most often admit patients to medical-surgical nursing units; thus, medical-surgical nurses are seeing more inpatients with SCD and need to be able to access resources to manage their pain. Oncology nurses may be an important resource for medical-surgical nurses; therefore, understanding similarities and differences of cancer pain and the pain of SCD is important.

Cancer Pain and Pain of Sickle Cell Disease

Pain is the most common reason individuals seek care (Fox, Berger, & Fine, 2000), and is the hallmark of SCD. Opioid analgesics have a significant role in pain management of both diseases. In the case of SCD, Solomon (2010) found that opioid administration often was not in compliance with recommendations, resulting in delayed pain control and premature decisions on disposition, leading to early return visits and possibly avoidable hospitalizations. Although similarities exist, significant differences also can be found when comparing cancer pain and the pain of SCD. Ballas (1998) stated that the most important difference between cancer pain and the pain of SCD is their underlying pathophysiology.

Pathophysiology

Cancer pain

The etiology of cancer pain is well documented and most often is caused by direct tumor involvement, nerve compression or infiltration, hollow viscus involvement, or metastatic bone disease (Ballas, 1998). Cancer pain most often is described as chronic, can be somatic or visceral, and usually is localized (Ballas, 1998). Pain experienced by individuals with cancer may be related to stage and type of cancer or even the delayed effects of treatment such as radiation therapy or chemotherapy.

Sickle cell disease pain

In contrast, the etiology of SCD pain is not as well understood. For many years, pain was thought to be caused by ischemia from sickled red blood cells disrupting perfusion. Recently, inflammation was found to play a significant role in the pathophysiologic complications of SCD (Ballas et al., 2012). On presentation, no objective clinical characteristics exist that can support the individual’s subjective reports of pain in SCD.

Smith and Alsalman (in press) offered other important differences in cancer pain and SCD pain. They described cancer pain as predictable, not questioned, and having many objective correlates. In contrast, the pain of SCD is described as unpredictable, questioned by healthcare providers, and having few objective correlates. Significant pain in a patient with cancer can indicate progression of the disease and perhaps a terminal event. However, experiencing pain throughout their lifetime is not uncommon for individuals with SCD. Additional differences include that patients with cancer receive longitudinal specialty care with few to no visits to emergency departments, whereas individuals with SCD, particularly adults, tend to receive episodic care and frequent emergency department visits (Smith & Alsalman, in press). When individuals with SCD present to emergency departments, healthcare providers, including nurses, often are apprehensive about their pain management needs. That apprehension about the validity of pain often continues during inpatient admission.

Role of the Oncology Nurse

Nurses are integral in assisting individuals with cancer and SCD in managing their pain. Individuals with cancer most often experience some degree of pain during and after treatment, and oncology nurses have experience with managing this pain. Oncology nurses can have two significant roles to improve the pain management experience of individuals with SCD, patient advocate and educator.

Patient Advocate

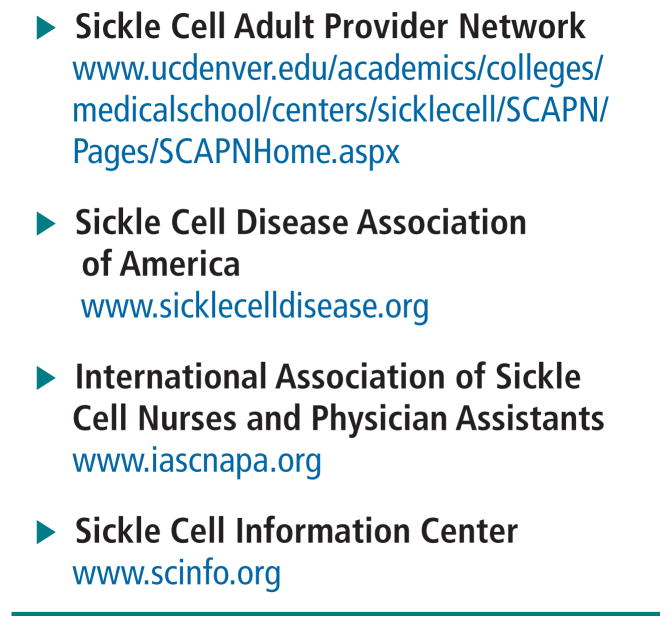

At times of acute pain, particularly when no objective correlates exist, patients with SCD may not be able to advocate for themselves. Although McCaffery and Pasero (1999) defined pain as “whatever the experiencing person says it is, existing whenever he/she says it does” (p. 17), the validity of pain reports of individuals with SCD often are questioned. In addition to delivering medications and treatments, nurses are responsible for communicating ongoing patient needs to other members of the healthcare team. Resources that may improve the knowledge base of oncology nurses about SCD and their pain management needs can be found in Figure 1. Those SCD-specific resources compliment organizations such as the Oncology Nursing Society, American Pain Society, and National Comprehensive Cancer Network, which offer a variety of guidelines and educational materials on care of individuals with acute and chronic pain. Oncology nurses are in a key role for advocating for appropriate, adequate pain management for all individuals, including those with hematologic disorders such as SCD.

FIGURE 1.

Sickle Cell Resources for Nurses and Patients

Educator

The role of educator is foundational to the profession of nursing. In the care of patients with SCD, oncology nurses can help to educate two important populations—other nurse providers and individuals with SCD and their families. By educating others, oncology nurses can enhance the pain management experience of individuals with SCD.

One specific group of nurses that may benefit from the pain management experience of oncology nurses are medical-surgical nurses. The experiences of oncology nurses with pain management may provide insight into the uniquely complex pain management needs of individuals with SCD.

Oncology nurses also can play an important role in educating patients and families living with SCD. Jenerette and Brewer (2011) suggested teaching individuals with SCD who frequent the emergency department to use the SBAR (situation, background, assessment, recommendation) strategy to communicate when they seek care in the emergency department; pilot intervention data are still being collected. The SBAR strategy also could be taught to inpatients with SCD, as well as other populations with chronic pain conditions. Being able to adequately communicate needs is an important first step in having pain management needs met by healthcare providers.

Conclusion

Care of individuals with SCD is directed toward collaborative care with foci on alleviating pain and other symptoms associated with discomfort. Ongoing teaching and support is important in caring for individuals with complex, acute, and chronic symptomatology. Pain assessment and management require innovative, collaborative nursing interventions that will improve the quality of care and life of these individuals. Oncology nurses are well positioned to make positive contributions to the health outcomes of individuals with SCD, particularly in the area of pain management.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded, in part, through a National Institute of Nursing Research grant (K23NR011061) to Jenerette and a National Cancer Institute grant (5R25CA116339) to Leak. The authors take full responsibility for the content of the article. The authors did not receive honoraria for this work.

Footnotes

No financial relationships relevant to the content of this article have been disclosed by the editorial staff.

Contributor Information

Coretta Jenerette, School of Nursing, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Ashley Leak, Health Policy and Management in the Gillings School of Global Public Health and an adjunct assistant professor in the School of Nursing, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

References

- Ballas SK. Sickle cell pain: Progress in pain research and management. Vol. 11. Seattle, WA: International Association for the Study of Pain; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ballas SK, Kesen MR, Goldberg MF, Lutty GA, Dampier C, Osunkwo I, Mulak P. Beyond the definitions of the phenotypic complications of sickle cell disease: An update on management. Scientific World Journals. 2012:949535. doi: 10.1100/2012/949535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox C, Berger D, Fine P. Pain assessment and treatment in the managed care environment: A position statement from the American Pain Society. Case Manager. 2000;11(5):50–53. doi: 10.1067/mcm.2000.110313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassell KL. Population estimates of sickle cell disease in the U.S. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2010;38(4 Suppl):S512–S521. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenerette C, Brewer C. Situation, background, assessment, and recommendation (SBAR) may benefit individuals who frequent emergency departments: Adults with sickle cell disease. Journal of Emergency Nursing. 2011;37:559–561. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2011.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo YF, Goodwin JS. Association of hospitalist care with medical utilization after discharge: Evidence of cost shift from a cohort study. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2011;155:152–159. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-155-3-201108020-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaffery M, Pasero C. Pain: Clinical manual. 2. St Louis, MO: Mosby; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Mousa SA, Al Momen A, Al Sayegh F, Al Jaouni S, Nasrullah Z, Al Saeed H, Qari M. Management of painful vaso-occlusive crisis of sickle-cell anemia: Consensus opinion. Clinical and Applied Thrombosis/Hemostasis. 2010;16:365–376. doi: 10.1177/1076029609352661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platt OS, Brambilla DJ, Rosse WF, Milner PF, Castro O, Steinberg MH, Klug PP. Mortality in sickle cell disease—Life expectancy and risk factors for early death. New England Journal of Medicine. 1994;330:1639–1644. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199406093302303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees DC, Williams TN, Gladwin MT. Sickle-cell disease. Lancet. 2010;376:2018–2031. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61029-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith WR, Alsalman AJ. Methadone prescribing in the sickle cell patient. In: Cruciani R, Knotkova H, editors. Handbook of methadone prescribing and buprenorphine therapy. New York, NY: Springer Science and Business Media; (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Smith WR, Jordan LB, Hassell KL. Frequently asked questions by hospitalists managing pain in adults with sickle cell disease. Journal of Hospital Medicine. 2011;6:297–303. doi: 10.1002/jhm.933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith WR, Penberthy LT, Bovbjerg VE, McClish DK, Roberts JD, Dahman B, Roseff SD. Daily assessment of pain in adults with sickle cell disease. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2008;148:94–101. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-2-200801150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon LR. Pain management in adults with sickle cell disease in a medical emergency department. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2010;102:1025–1032. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30729-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]