Summary

Ghana successfully passed a Mental Health Act law in March 2012. The passing of the Act was a culmination of a lot of work by various individuals and institutions spanning several decades. Finally there is a raised prospect of the delivery of a better quality mental healthcare and also the protection of human rights of people with mental disorders in Ghana. This paper identifies and describes clusters of related potential problems referred to as ‘challenges’ involving different aspects of service delivery, which are anticipated to be encountered during the implementation of the law. Finally, it cautions against the risk of allowing the new mental health law to add a new ‘legal’ burden to a list of perennial ‘burdens’ including underfunding, serious levels of understaffing and plummeting staff morale, which bisected earlier attempts at implementing a similar law that laid fallow for forty years.

General Introduction

According to the World Health Organisation, mental health disorders accounted for 12% of the global disease burden in 2000. This figure is estimated to rise to 15% in 2020, when unipolar depression is predicted to rise from being the fourth to the second most disabling health condition in the world.1

Estimates of Prevalence and Burden of Mental Disorders in Ghana

Data on the epidemiology of mental disorders in Ghana is inadequate and outdated thereby limiting the ability to compute the burden of these disorders. 2 A population-based epidemiological study in 1984 estimated the prevalence of schizophrenia to be 2/1000.3 There are no hard figures on the epidemiology of mental illness in Ghana. The convention then is to use the WHO epidemiological formula for the estimation of psychiatric problems in any given population. By this formula, 10% of any given population suffers from neuropsychiatric conditions and 1% from severe mental illness at any one time.4 Using that formula, and assumption based on the census5 that Ghana's population is 24 million, it is estimated that approximately 240,000 people do suffer from severe mental disorders and 2,400,000 suffer from some form of mental disorder. But in 2008 there were only 10 psychiatrists in Ghana compared to a 13074 doctors to Ghana's population of 24,252,438 population.6

The current Mental Health Act

The passage of the Mental Health Act 2012 by parliament in March 2012 is a major milestone in addressing mental health as a public health issue and also in the protection of the human rights of people with mental disorders in Ghana. The last major revision of mental health law was undertaken in the late 1960s, culminating in the enactment of the Mental Health Decree, NRCD 30, in 1972.7

Unfortunately over the forty years of its existence, the Mental Health Decree (NRCD 30), was not implemented. Rather, since the early 1990s several unsuccessful attempts were made to enact a new mental health law. Before 2004, The Law Reform Commission (LRC) was involved in revisions of the 1972 Decree. It is surprising however that these earlier revisions including the Mental Health Law, 1990, 8 were not enacted, not even during periods of constitutional rule.

The process that culminated in the passage of the Mental Health Act by Parliament in March 2012 was initiated in 2003. From 2004, financial and technical support was given by the Mental Health Department of the World Health Organization (WHO).

Over the last 8 years, the process of formulating and revising the legislation has involved a series of consultations with a wide variety of international and local stakeholders. The role of the LRC in the recent process of formulating the 2012 Act is uncertain.

Deliberations in Parliament

The report of the Select Committee on health was to a very large extent adopted by the House save some few provisions which needed a little modification.

However, provisions deemed of grave importance and which often involved serious debates resulted in such provisions being stood down to enable further consultation to be made. One of the issues was in whom to vest the powers of appointment of the Hospital Director and Clinical Coordinator.

The house decided to vest the power to appoint the Hospital Director and Clinical coordinator psychiatric hospitals, in the Board of the Mental Health Authority rather than the President of the Republic.

Clause 58(4) (seclusion and restraint) was withdrawn for reasons of practical impossibilities and the need not to legislate practice. It was the opinion of the House that personnel of the facility should be given some discretion to enable them assess each situation and apply the best procedure for any given situation.

Clause 63(2) (Employment rights) was also amended to clearly state the role of employers in assistance required of them when they have reasonable cause to believe and is suffering from mental illness.

Of particular importance is the inclusion of a new clause that seeks to establish a Mental Health Fund which is tasked with the responsibility of managing all funds and raising additional funds through a number of stated avenues. The object of the Fund is to provide financial resources for the care and management of persons suffering from mental disorders.

The UN Convention for the Rights of Persons with Disability (UNCRPD) a piece of International legislation which has huge implications for community rehabilitation in mental health care was not even discussed in the parliamentary debate leading to the Bill.

Given that the select committee on ESW has the primary responsibility for disability issues, it needed to have been explicitly involved as an entity, but was not.

Congratulations are due to the leadership within the Mental Health Unit of the Ghana Health Service and various research projects which supported the process and mental health advocates and activists, the media, NGOs civil society and service users The members of the parliamentary select committee for health and other legislators who supported the passage of the Act, equally deserve commendation.

Post Mental Health Act enactment advocacy on the UNCRPD

The advocacy by various groups and individuals towards the ratification of the UNCRPD by the Government of Ghana, was indeed timely. Ghana ratified the UNCRPD in July, 2012. The UNCRPD makes community treatment and rehabilitation for persons with mental disability mandatory and binding.9 The implications of the UNCRPD for the mental health Act and mental healthcare delivery in Africa have been outlined by Bartlett10 and specific recommendations to make the Mental Health Act compliant with the UNCRPD by Ssengooba.11

We foresee six main challenges to the Health and Social Services in Ghana posed by the new Mental Health Act. These are organizational, human resource, social services, legal and judicial, role of the Commission for Human Rights and Administrative Justice (CHRAJ) and information systems which are examined in turn.

Health System Organizational Challenge

The Mental Health Services have, by and large, remained attached to their historical origins within the curative health framework.12 The extension of psychiatric facilities to units within Regional and District Hospitals is consistent with the curative paradigm. Community psychiatry is viewed within this framework as ‘outreach’ services from psychiatric facilities. The application of public health principles to mental health services has not been tried.

The Mental Health Unit (MHU) is organizationally placed within the Institutional Care Division (ICD) of the Ghana Health Service. The offices are located in the Accra Psychiatric Hospital. From this location the MHU governs the three state psychiatric hospitals and operates a national community psychiatric nursing service.13 Oversight for the regional psychiatric units is provided by their respective regional health administrations. Community psychiatric nurses are paid and supervised by their respective district health administrations. There is no operational link between the Directorate of Public Health in the Ghana Health Service (GHS) and the Mental Health Unit.14 There is no organizational or structural representation of the MHU within the Ministry of Health hierarchy.

The low morale and dissatisfaction of mental health professionals and their perceived negative treatment within the Ghana Health Service over the years may have been a motivating factor in the formulation of the original version of this Act, which proposed a Mental Health Service separate from the Ghana Health Service. This observation might have informed a view reported to have been expressed by a prominent psychiatrist that mental health professionals were ‘misfits’ in the Ghana Health Service (GHS).15 However the idea of a Mental Health Service separate from the Ghana Health Service was not adopted.

The parliamentary select committee on health took a different view, and proposed the establishment of a Mental Health Authority (MHA) within the existing Ministry of Health (MOH) and GHS organizational framework, citing duplication of roles and functions as potential disadvantages of a parallel mental health service. 16 The actual location of the proposed MHA within the MOH and the organisational relationships between the MHA and the GHS Council and GHS were not prescribed by parliament. 16 However the Mental Health Service along with the National Ambulance Service, Teaching Hospitals Authority, Hospitals, Health Stations, Health Centres of Security Service, etc. are excluded from the General Health Bill. 17 Several scenarios of the location of the MHA within the MOH and GHS have been proposed.

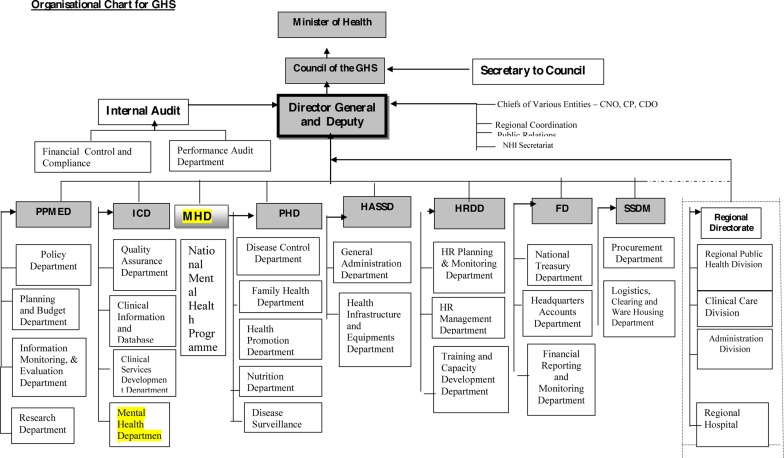

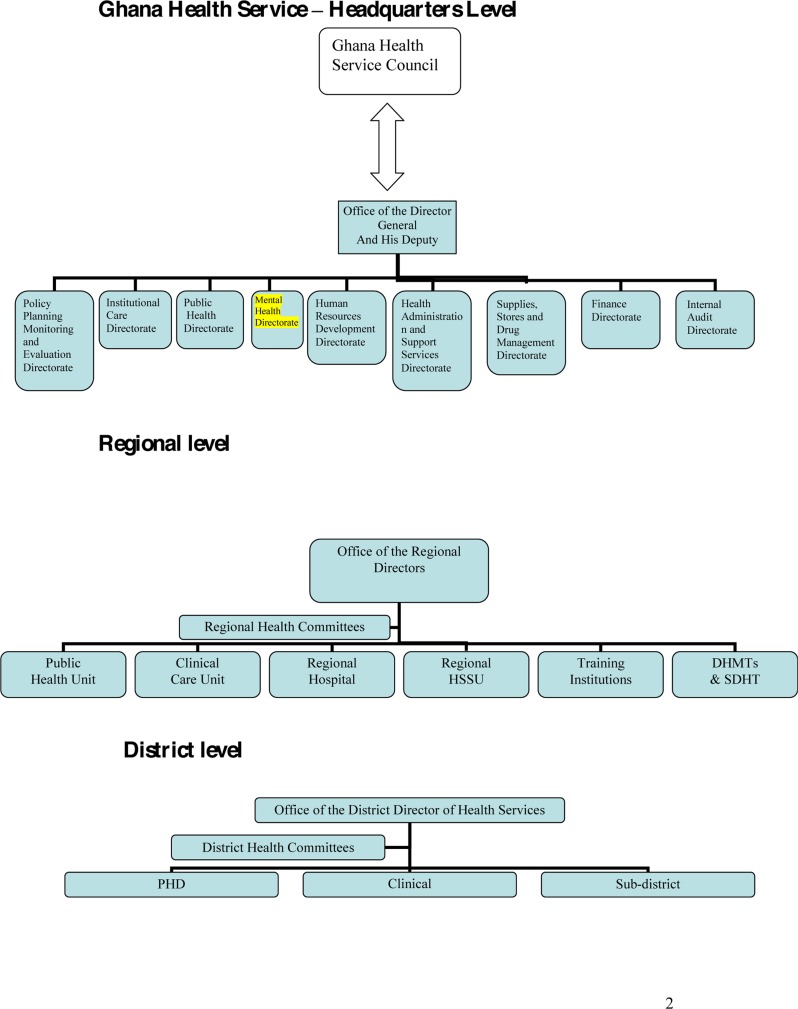

If the principles underpinning the health sector reforms in the early 1990s are to be adhered to (i.e. the principle of policy/service-provision divide), the MHA would be responsible for the policy formulation, regulation and enforcement whilst a mental health programme within the GHS would be responsible for implementation of public mental health services. The WHO espouses the principles of decentralization and integration of mental health within general health services. In relation to the current Act in Ghana, various scenarios of the location of the MHA and a mental health programme in the GHS are illustrated in the organograms attached in the appendix. In the organograms, Organogram 1 deals with the policy formulation, regulation and enforcement. Organogram 2 shows the current position of the Mental Health Unit under the Institutional Care Division and the proposed Mental Health Division with a national mental health programme; both are highlighted in Yellow. Organogram 2 deals with the framework for service provision in the GHS.

Three scenarios are considered under the former. Firstly, the MHA might be conceptualized as a regulatory body operating on the same basis as the Ghana Medical and Dental Council. Secondly, the MHA might be modeled after the National Health Insurance Authority in terms of its direct access to the Minister of Health. Finally the MHA might be placed as a directorate under the purview of the Chief Director of the MOH. In terms of service provision, a national mental health programme fully integrated into a decentralized general health care will support equitable geographic access to mental health care provision.

Mental Health Human Resource Challenge

A fully operational Mental Health Act depends on, among others, the availability and involvement of an adequate number of well-trained multidisciplinary professional mental health workforce (psychologists, mental health social workers, occupational therapists, nurses and doctors), supported by mental health act administrators and interested and well-motivated legal practitioners. Historically, the discussion on human resource limitations in mental health has focussed on the shortage of psychiatrists and psychiatric nurses to the neglect of attention for the need for psychiatric social workers who are internationally recognised as the advocates for the protection of the human rights of people with mental disorders. In a broader sense, social workers ensure that people with mental disorders get what society has stipulated is their due. But the supply of and the role of psychiatric social workers in the implementation of the Act, has not been explicitly addressed.

Some sub-specialties of mental health: Forensic, child and adolescent, learning disability and addiction psychiatry, are all lacking in the country. For example, forensic mental health services where mental health services interface with the justice system may require special attention without which the full realisation of the potential of the mental health act may be severely compromised. At the moment, there is no forensic psychiatrist in the country to provide that specialist input.

The Ghana Human Resource for Health Country profile does not adequately capture issues on the mental health workforce.18 A human resource strategy which systematically addresses recruitment, retention and professional development of mental health workforce (within and outside the health sector) is urgently required

Social Services Challenge

The present workforce situation and conditions of service of general social services in Ghana do not hold out much hope regarding the ability of the social services to provide adequate numbers of social workers well-skilled in mental health to support the implementation of the Mental Health Act.19

Under the Act, psychiatric rehabilitation is not considered as a clinical issue for psychiatric services, but rather the duty of the Minister responsible for Social Welfare. The community-based rehabilitation programme in Ghana is mainly restricted to the needs of the physically disabled without acknowledgement of the provision for community rehabilitation needs of people with mental disability. Although the definition of disability as defined in the Persons with Disability Act includes people with mental disorders, mental disability is not addressed within the disability framework in Ghana.

Therefore, there is a need to address this apparent anomaly and integrate mental health into the community-based rehabilitation within social services in Ghana.

At a higher organisational level, cross or reciprocal representation between the National Council of Persons with Disability (NCPD) and the Board of the proposed Mental Health Authority might be mutually beneficial in advancing social care provision and community rehabilitation needs for people with mental disability.

Legal and Judicial challenge

The availability of a legal forum where people can go to seek enforcement or redress to the breach of their rights, trained health professionals and administrators, advocates to assist people in their representations, are necessary conditions for the implementation of the mental health act. These facilities will need to be put in place in Ghana as soon as possible. Indeed the congestion of the state psychiatric hospitals and consequent violation of the human rights of patients can be attributed in part to the failure of successive health administrators to implement the Mental Health Tribunal Procedures.

A few prominent human rights lawyers and NGOs, notably the Human Rights Advocacy Centre, are the visible advocates for the rights of persons with mental illness whose human rights have been breached. 20 HelpLaw Ghana, is another NGO/Charity established with the sole purpose to provide free services to the poor and less privileged in Ghana.

But the extent of their involvement with patients in psychiatric facilities remains uncertain.21

The law faculties of the University of Ghana and Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, do not offer elective courses of study in health law hence lawyers trained in Ghana qualify without exposure to health law training, let alone mental health law. Without lawyers who are trained in health law to help interpret, advocate and enforce the mental health act, to protect patients' rights and implementation of the Act the risk of non-fulfilment or breach of patients' rights will be real. The Act stipulates that the Mental Health Review Tribunals (MHRTs) are presided over by senior lawyers. In the earlier drafts of the Act, it was envisaged that the Mental Health Authority would be responsible for the regulation of the MHRTs. It has been suggested that as the MHRTs are quasi-judiciary in nature, their regulation should be from the Judicial Services and not by the Mental Health Authority. This arrangement if put in place would guarantee a higher level of independence and impartiality of the MHRTs. In the Mental Health Decree, NRCD 30 1972, no provision was made for receiving and investigating complaints from detained patients. It might be reasonably assumed that the appeals process would take complaints into account or that the hospitals might have a robust grievance and complaints procedure. The Mental Health Act, which clearly places more emphasis on the patient, is more explicit in this regard and makes provision for complaints from detained patients to be heard and investigated. A high turnover of complaints should therefore be anticipated and prepared for.

A review of enactments relevant to the mental healthcare needs to be undertaken to bring them in line with the mental health Act. This might result in consequential amendments. For example the decriminalization of suicide requires amendment the Criminal code, 1960, Act 29.

The Role of CHRAJ

It is common knowledge that the Commission for Human Rights and Administrative Justice (CHRAJ) receives and investigates complaints from and on behalf of patients who suffer from mental illness, particularly those on admission to various psychiatric hospitals. In this regard it is not unreasonable to assume that in respect of receiving and investigating complaints, that CHRAJ is the de facto Mental Health Review Tribunal.

In recent times, CHRAJ has undertaken an advocacy role in respect of Persons with Disability and the calls for the implementation of the legislative instrument for the Persons with Disability Act, 2006 (Act 715). A strong link between clause 72 of the Mental Health Act, (which requires the Minister responsible for Social Welfare to make provision for the psychosocial rehabilitation and after-care services of mental health patients, including supervision, rehabilitation and vocational training), and clause 15 of the Persons with Disability Act, (which requires that, as far as practicable, persons with disability shall be rehabilitated in their communities to foster their integration), would ensure that people with mental illness who become psychosocially disabled as a result of their mental disorder, will benefit from the provisions of this enactment. Equally the Rights of Persons with disability (clauses 1–15 of the Ghana Disability Act 2006) might be applicable to a proportion of the mentally ill who suffer psychosocial disabilities during the course of illness. It is not certain that the CHRAJ curriculum on the Human Rights includes the Rights of Persons with Mental Illness.

Finally, could the roles and functions of the Visiting Committees enshrined in the Mental Health Act be delegated to an independent and decentralized organization such as CHRAJ? We suggest it may be useful to explore that possibility.

Mental Health Information System Challenge

Another challenge for the health and social services is the need to develop an information system to support mental health service delivery. This would include a mental health act administration information systems as well as a general mental health information system integrated right through to the district level.

Healthcare delivery in general is an information-intensive undertaking and is particularly so in mental healthcare. Decentralisation of mental health services to the district and emphasis on community-based mental healthcare delivery means more demands will be made on the existing information system which is mostly paper-based. The fact that the Mental Health Act prescribes certain mandatory sequence of activities such as Mental Health Review Tribunals taking place during a maximum set period after a patient is admitted under the Act, means the existing Mental Health Information System (MHIS), no matter how flawed, has to support such imposed legal requirements under the Act. There will be serious implications, for example, to tell the lawyer of a detained patient, whose case is waiting to be heard by the tribunal that his/her psychiatric case notes could not be found. But under the current system, lost case notes are so common that they tend to be accepted as normal. Therefore, implementation of the Act requires a major overhaul or complete re-design of the current MHIS to support efficient mental healthcare delivery under the new stricter regime of the Act.

This then calls for the consideration of an introduction of (the more efficient) ICT-based Mental Health Information System to operate in tandem with the current paper-based system and eventually replace it altogether. There exists the beginnings of a partially computerised Mental Health Information System, set up as part of the Mental Health & Poverty Project (MHaPP) in the three state psychiatric hospitals.22 This MHIS enables a uniformity of data collection across the three hospitals and also opens up the potential for extending the range of mental health-related indicators on the Director General's Dashboard of health indicators.23 There are plans by the GHS to extend this to other districts.

Although the MHIS is a major leap forward by comparison, it is designed mainly to support administrative functions within the institutional care rather than a patient-centred Electronic Healthcare Record System (EHCR) that supports community-based mental healthcare delivery. An EHCR now needs to be developed with a view of scaling up to a national scale platform, interfacing with the general healthcare system at various levels. Such a platform will greatly assist practitioners in the provision of more effective clinical care based on present and past documented information. Above all, it will minimise the risk of community mental health staff carrying psychiatric case notes wherever they go in the community.

Fortunately, with the current high penetration of mobile phones, it is now possible to have a mobile-based tele-psychiatry platform that can support community-based clinical care including e-prescriptions, laboratory and radiological investigations etc. using all available mobile devices. The data can then be aggregated, anonymised and analysed data from these clinical databases. Setting up such a platform and getting it to interphase with the general healthcare system at the regional and district levels may be another practical hurdle. A careful transition from the current MHIS will be needed to avoid a potential tragic information systems failure that may add to the anticipated costs.24–26

Financial Challenge

The organisational, human resource and legal challenges discussed above require reasonable resource investment if they are to be surmounted. Mental Health financing needs to be re-examined systematically from a broad variety of viewpoints. A proposed policy and legal framework for such an exercise is outlined in the table attached in the appendix. It is not feasible for the health sector alone to bear the burden of mental healthcare costs. This expectation is also unrealistic given the constraints on the health budget. Careful mapping of potential sources of funding is the first step in ensuring that mental health care is not underfunded.

The Mental Health Act seeks to introduce several new components to mental healthcare delivery which would require an augmentation of the sector's financial base if it is to be workable. To this effect the Act proposes the establishment of a Mental Health Authority with a governing board and several departments to perform roles that are parallel to the Ghana Health Service. It also proposes the setting up of visiting committees in all ten regions to conduct periodic inspection of mental health facilities. If all these administrative bodies are to be adequately catered for, the meagre fiscal arrangement that currently exists may not be able to sustain the new regime, and may increase the resource going to the top management rather than the actual frontline patient care. This will burden the already overstretched national budget to work against the spirit of the Act.

Extending the mandate of some existing institutions and strengthening their capacity to deal with mental health related matters could curtail the financial burden, which might result from the creation of these new institutions. For instance, the role that the proposed visiting committees are to perform can in the interim be performed by CHRAJ conveniently performed in the short to medium term, by the Commission on Human Rights and Administrative Justice (CHRAJ), which is the de facto Mental Health Tribunal, through its existing decentralised regional and district offices. This would go a long way to reduce the cost of implementing the objectives of the Mental Health law.

Also the logistical improvements that might be required to build the capacity of CHRAJ to undertake its new mandate might also improve the capacity of CHRAJ to perform its existing mandate.27 And importantly, CHRAJ will provide informed, independent and objective oversight which an oversight body may lack, at least, in the first two areas.

Although the Mental Health Act proposes the setting up of a mental health fund, it is unclear how this fund is to be sourced and sustained. The government in its 2012 budget intimated that the total amount allocated to the health sector took into consideration the intention to pass the mental health bill. An interesting question is: Did the drafters of the proposed bill project the cost implications of implementing the Act? If so, how much of the national budget on health was factored in the budget for the implementation of the Act?

Furthermore, a critical analysis of the Act, would reveal that the problem of mental health is not just a ‘health matter’, but has ‘social’ implications as well. In this regard, the financing of mental health care should not be the sole responsibility of the Ministry of Health. There should be some collaboration between the Ministries of Employment and Social Welfare, Finance and Economic Planning and Local Government since they have or ought to have some responsibility and interest in the matter. The ministries of Employment and Social Welfare and Local Government are expected under the Act to work towards the rehabilitation of persons suffering from mental disorder. It is expected that the mental health budget would initiate the creation and maintenance of rehabilitation centres.27

The Act proposes the setting up of a fund. It is not clear how much funding would be required to run an effective and efficient mental health service. The health sector budget allocation for mental health is just over 2.2% versus the WHO-recommended 15%, a disproportionately small allocation even by the standards of a resource-constrained country.28

This has resulted in the psychiatric hospitals being to some extent supported by charitable donations from churches and individuals.

The additional human resources (including mental health tribunal judges, lawyers representing patients with legal aid, etc.) and logistics required to run what is essentially a ‘mini legal system’ within the mental health services cannot be run with this level of funding if rampant miscarriages of justice and costs due to compensation for such miscarriages are to be avoided. Community-based care for people with mental disorders deceptively appears to be cheap but evidently not. Expansion of mental health services from psychiatric hospitals based in the south of Ghana to a wide range of regional and district hospitals with ambulatory services led by district nurses may require substantial investment in setting up, operation and maintenance. But chronic underfunding over the years has resulted in the current poor state of the mental health service in Ghana. Under the National Health Insurance regulation 2004, mental health care services are provided free of charge at the point of delivery. The extent to which this provision of free service will be successfully implemented within hospitals and in the community without further deterioration in the quality of present levels is unclear. It also does not give hope to expect that the minimum standard of quality of care required under law may be met given that it requires a comparatively higher level of funding.

Given the resource-demanding uncertainties discussed above, we entreat the future drafters of the mental health act legislative instrument (LI) to provide clarification for the sources of financing to remove the uncertainties without which any meaningful planning becomes illusive. Also because the following domains, namely, Decentralization policy, Health policy and legislation, Social protection, disability and access to justice and the various acts underpinning them, oblige them to contribute to mental health care, we propose that the LI stipulates in financial terms their contribution to the proposed mental health fund. (See Appendix, Policy and Legal framework for financing mental healthcare in Ghana)

Conclusion

Ghana waited anxiously for the Mental Health Act to be passed into law but the preparations undertaken at the political, organisational and structural level towards its implementation appear slow. The law makes new demands on the Ministry of Health, the Social Services, the legal and judicial systems and the education services. With these fresh challenges, the question is: How willing and able are these institutions in meeting the challenges presented?

We hailed the passing of the Act as the ‘new dawn’ for mental health, but now Ghanaians are waiting in hope that this law will not lie fallow for forty years as befell its predecessor.

Dedication

We wish to dedicate this paper to the memory or Professor Samuel Nii Ayi Turkson, former head of Department of psychiatry, University of Ghana Medical School, who passed away on 27 October 2011.

Appendix I. Policy and Legal Framework for financing mental healthcare in Ghana

| POLICY/LEGAL FRAMEWORK | EXAMPLES |

| ECONOMIC POLICY AND BUDGET | Budget allocation to

|

| GHANA SHARED GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT AGENDA (GSGDA) COSTING FRAMEWORK |

|

| DECENTRALIZATION POLICY |

|

| HEALTH POLICIES AND LEGISLATION |

|

| SOCIAL PROTECTION |

|

| DISABILITY |

|

| ACCESS TO JUSTICE |

|

Figure 1.

Organogram Scenario 1

Figure 2.

Organogram scenario 2

References

- 1.World Health Organization, author. Mental Health: A Call to Action by World Ministers. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Read U, Doku V. Mental Health Research in Ghana: A Literature Review. Ghana Medical Journal. 2012 Jun;46(2 Supplement) 2012. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sikanartey T, Eaton WW. Prevalence of schizophrenia in the Labadi district of Ghana. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1984;69:156–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1984.tb02481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization, author. The World Health Report 2001: Mental Health, New Understanding, New Hope. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghana Statistical Service, author. 2010 Population and Housing Census-Summary report of final results. 2012. May, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghana Health Service, author. The Health Sector in Ghana-Facts and Figures. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forster EB. Forensic attitudes in the delivery of mental health care in Ghana. Ghana Medical Journal. 1971;10(1):52–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Law Reform Commission, author. Mental Health Law. Ghana: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 9.United Nations, author. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, General Assembly A/61/611. 2006. Dec 6, [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bartlett P, Jenkins R, Kiima D. Mental health law in the community: thinking about Africa. International Journal of Mental Health Systems. 2011;5(1):21. doi: 10.1186/1752-4458-5-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ssengooba M. Like a Death Sentence: Abuses Against Persons with Mental Disabilities in Ghana. 2012. Oct 2nd, [Google Scholar]

- 12.Forster EB. A historical survey of psychiatric practice in Ghana. Ghana Medical Journal. 1962;1:25–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ofori-Atta A, Read U, Lund C. A situation analysis of mental health services and legislation in Ghana: challenges for transformation. African Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;13(2) doi: 10.4314/ajpsy.v13i2.54353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Asare JB. Mental Health in Ghana. Ghana Medical Journal. 2001;35(3):105. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Public Agenda, author. Mental Health Practioners Kick Against Ghana Health Service. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Report of the Committee on Health on the Mental Health Bill. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17.General Health Services Bill. Ghana: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghana Health Workforce Observatory, author. Ghana Human Resources for Health Profile. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laird SE. African Social Services in Peril, A Study of the Department of Social Welfare in Ghana under the Highly Idebted Poor Countries Initiative. Journal of Social Work. 2008;8(4) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Human Rights Advocacy Centre, author. Human Rights Cases in Ghana. [15 November 2012.]. www.hracghana.org/headlines/hrcases-made-simple/

- 21.HelpLaw Ghana. 2012. [15 November 2012]. http://www.help-law.org/?

- 22.Mental Health and Poverty Project, author. A new mental health information system for Ghana. 2010. [22 November 2012]. http://www.health.uct.ac.za/usr/health/research/gro upings/mhapp/impact_case_studies/Ghana.pdf.

- 23.Ofori-Atta A, Lund C, Mirzoev T, Omar M. Mental Health Information System in Ghana. 2010. [14 January 2013]. http://www.dfid.gov.uk/R4D/PDF/Outputs/MentalHealth_RPC/MHPB16.pdf.

- 24.Heeks R. Health information systems: failure, success and improvisation. International journal of medical informatics. 2006 Feb;75(2):125–137. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2005.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lederman RM, Parkes C. Systems failure in hospitals--using Reason's model to predict problems in a prescribing information system. Journal of medical systems. 2005;29(1):33–43. doi: 10.1007/s10916-005-1102-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bourn M, Davies CA. A prodigious information systems failure. Topics in Health Information Management. 1996;17(2):34–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Akondo N. Rethinking Mental Health Bill: Some Thoughts On Financial Implications. 2011. [15 November 2012]. http://opinion.myjoyonline.com/pages/feature/201 203/82400.php.

- 28.Antwi-Bekoe T, Oheneba M. Financing Mental Health Care in Ghana. 2009. [14 January 2013]. http://www.basicneeds.org/download/PUB%20%20Financing%20Mental%20Health%20Care%2 0in%20Ghana%20%20BasicNeeds%20Ghana%202009.pdf.