Abstract

East Chicago, Indiana is a heavily-industrialized community bisected by the Indiana Harbor and Ship Canal, which volatilizes ~7.5 kg/yr polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs). In contrast, the rural Columbus Junction, Iowa area has no known current or past PCB industrial sources. Blood from children and their mothers from these communities were collected April 2008-January 2009 (n=177). Sera were analyzed for all 209 PCBs and 4 hydroxylated PCBs (OH-PCBs). Sum PCBs ranged from non-detect to 658 ng/g lw (median = 33.5 ng/g lw). Sum OH-PCBs ranged from non-detect to 1.2 ng/g fw (median = 0.07 ng/g fw). These concentrations are similar to those reported in other populations without high dietary PCB intake. Differences between the two communities were subtle. PCBs were detected in more East Chicago mothers and children than Columbus Junction mothers and children, and children from East Chicago were enriched in lower-molecular weight PCBs. East Chicago and Columbus Junction residents had similar levels of total and individual PCBs and OH-PCBs in their blood. Concentrations of parent PCBs correlated with concentrations of OH-PCBs. This is the first temporally- and methodologically-consistent study to evaluate all 209 PCBs and major metabolites in two generations of people living in urban and rural areas of the United States.

INTRODUCTION

Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) are anthropogenic persistent organic pollutants historically used in a variety of applications including capacitors, transformers, lubricants, plastics, adhesives, and carbonless copy paper.1 Despite discontinued production in the United States in 1977, PCBs persist in the environment and in humans. A major metabolic pathway for PCBs in humans is hydroxylation via the Cytochrome P450 enzyme system, with direct insertion of the OH group or an intermediate epoxide formation followed by a 1,2-hydride shift (NIH shift).2 A large body of literature indicates that PCBs and their metabolites cause negative health effects including carcinogenicity3 and endocrine disruption.4 Children’s exposure to PCBs is particularly concerning because PCBs cause neurotoxicity and developmental disorders.5–7

PCB accumulation in humans is a function of an array of exposures including diet, dermal, inhalation, and direct transfer in breast milk from mothers to infants. Because PCBs are anthropogenic, it is commonly assumed that living in a community with PCB contamination will result in higher PCB body burdens. The overall research question we address here is ‘how does environment affect PCB body burden?’

Previous studies offer strong evidence that differing environments yield different PCB body burdens. DeCaprio et al. observed serum PCB profiles in some participants that were similar to the air profile above a nearby PCB-contaminated water body.8 Choi et al. found that babies born after dredging of the contaminated New Bedford Harbor had significantly lower PCB body burdens than babies born before and during the dredging.9 Costopoulou et al. discovered PCB concentrations were different in people living in urban compared to rural Greece.10 McGraw and Waller found evidence for airborne exposure to PCBs in a cohort of pregnant African-American women living in Chicago.11 Dirtu et al. found differences in levels of OH-PCBs, but not PCBs, in residents of two differently-contaminated European cities.12

Although several studies demonstrate the possibility of contributions to body burden from sources other than diet, few studies have been conducted on a large scale that compare two communities in a temporally- and methodologically-consistent manner. Few studies compare PCB accumulation in humans as a function of local industrialization or control for known predictors of PCBs in humans such as age, sex, and demographics. Our study uniquely includes the following three aspects: 1) we sampled blood in residents of two communities in the United States with similar demographics, one industrial and one rural; 2) our cohort includes adolescent children and their mothers; and 3) we analyzed for all 209 PCBs and major metabolites (OH-PCBs). We hypothesized that the concentrations and distribution of PCBs and OH-PCBs in blood would differ between the two communities and age groups. We further hypothesized that mothers would have higher concentrations than their children and that PCB concentration would correlate with OH-PCB concentration.

Study subjects from Indiana live in the urban community of East Chicago. It is a highly industrialized community of 32,400 people bisected by the Indiana Harbor and Ship Canal (IHSC) on the southern shore of Lake Michigan. Major industries in the area include a steel manufacturer (Mittal Steel USA, Inc.) and a gas refinery (BP Products North America, Inc.). The International Joint Commission designated IHSC as an Area of Concern due to extensive contamination with heavy metals, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, and PCBs.13 PCBs are particularly interesting to this community because of plans for a navigational dredge of IHSC. IHSC flows within 0.5 km of the junior and senior high schools and is a known source of airborne PCBs. Martinez et al. found that ~7.5 kg/yr PCBs volatilize from IHSC,14 and sediment core profiles show that dredging may increase this release by exposing highly contaminated deep sediments.15 It is unknown whether there are other sources of airborne PCBs in the community.

In contrast, the Columbus Community School District in Iowa is a rural community of 3000 people with no known current or historical PCB sources. The town of Columbus Junction was incorporated in 1893 and was historically a small railroad and steel community situated in a rural and agricultural setting. Residents of both East Chicago and the Columbus Junction area have lower median household incomes and are mostly Hispanic or African-American. Most students receive free or discounted school lunch.

In this paper we compare the levels of PCBs and OH-PCBs between residents in the two locations, compare mother and child body burdens, and investigate the metabolic relationship between PCBs and OH-PCBs in participants.

EXPERIMENTAL

Sample Collection

Serum samples were collected from junior high school-aged students and their mothers who were enrolled in the Airborne Exposures to Semi-volatile Organic Pollutants (AESOP) Study, a community-based participatory exposure assessment cohort study, between April 2008 and January 2009. In the first year of the study, serum was available for analysis from 41 mothers and their 44 children participating in East Chicago, and from 44 mothers and their 48 children in the Columbus Junction area. More than one child was enrolled from 6 participating families.

Blood and questionnaire data were collected from enrolled AESOP subjects who gave informed consent and assent under an established Institutional Review Board protocol. A standard veinapuncture procedure was used. Blood was drawn into empty glass Vacutainer tubes and allowed to clot for 30 minutes. The blood was centrifuged to fully separate the serum from cells. Serum was transferred from the Vacutainer tubes into glass vials with Teflon caps and kept frozen at −20 °C until extraction. Two serum samples were removed from the sample set after being accidentally stored in plastic vials instead of glass vials. Cholesterol and triglyceride concentrations were measured by the University of Iowa Diagnostic Laboratories, Iowa City, IA, USA.

Analytical

Extraction

The extraction, separation, derivatization, and cleanup methods employed are a modification of Hovander et al.16 Briefly, serum (4 g) was spiked with 5 ng of each surrogate standard PCB 14 (3,5-dichlorobiphenyl, AccuStandard, New Haven, CT, USA), deuterated-PCB 65 (2,3,5,6-tetrachlorobiphenyl-d5, Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Inc., Andover, MA, USA), PCB 166 (2,3,4,4′,5,6-hexachlorobiphenyl, AccuStandard) and 4′OH-PCB 159 (4-hydroxy-2′,3,3′,4′,5,5′-hexachlorobiphenyl, AccuStandard), denatured with hydrochloric acid (HCl) and 2-propanol, and extracted with 1:1 hexane:methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE). The extract was washed with 1% potassium chloride (KCl) and separated into PCB and OH-PCB fractions by liquid-liquid partitioning with potassium hydroxide (KOH) and hexane. The OH-PCBs were re-protonated with HCl (2 M) and extracted using 9:1 hexane:MTBE. OH-PCBs were derivatized to the methoxylated form (MeO-PCBs) using diazomethane. Lipids and interferences were removed from each fraction, first by mixing with concentrated sulfuric acid and then by passing the extract through a sulfuric acid-activated silica gel column. PCBs were eluted from the silica column with hexane, and MeO-PCBs were eluted with dichloromethane (DCM). All solvents were pesticide residue analysis quality and the reagent water for aqueous solutions was Optima quality (ThermoFisher Scientific).

Analysis and Quantification

The sample extracts containing PCBs were spiked with 5 ng each of internal standard PCB 204 (2,2′,3,4,4′,5,6,6′-octachlorobiphenyl, AccuStandard) and deuterated-PCB 30 (2,4,6-trichlorinatedbiphenyl-d5, Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Inc.) immediately prior to analysis. The PCB instrumental method applied is a modification of US EPA Method 1668.17 A gas chromatograph with tandem mass spectrometer (GC-MS/MS, Agilent 6890N Quattro Micro™ GC, Waters Micromass MS Technologies) in multiple reaction monitoring mode was employed to analyze samples for all 209 PCBs as 160 individual or co-eluting congener peaks. Concentrations are reported for 202 PCBs after standards and congeners that co-elute with the standards were removed from the data set. Additional details are in the Supporting Information.

The sample extracts containing MeO-PCBs were spiked with 5 ng internal standard PCB 209 (2,2′,3,3′,4,4′,5,5′,6,6′-decachlorobiphenyl, AccuStandard) immediately prior to analysis using gas chromatography with electron capture detection (GC-ECD, Agilent 6890N).

There are 837 possible monohydroxylated –PCBs,18 and while commercial standards are available for all 209 PCBs, they are not available for most monohydroxylated-PCBs. The extracts were analyzed for four OH-PCBs as MeO-PCBs: 4-MeO PCB 107 (2,3,3′,4′,5-pentachloro-4-methoxybiphenyl), 3-MeO PCB 138 (2,2′,3′,4,4′,5-hexachloro-3-methoxybiphenyl), 4-MeO PCB 146 (2,2′,3,4′,5,5′-hexachloro-4-methoxybiphenyl), and 4-MeO PCB 187 (2,2′,3,4′,5,5′,6-heptachloro-4-methoxybiphenyl). These congeners were selected because they are commonly reported hydroxylated metabolites in humans.19 MeO-PCB standards were purchased from Wellington Laboratories (Guelph, ON, Canada).

Congener mass calculation was performed by applying a relative response factor obtained from the calibration curve for each congener. Surrogate standards were used to adjust final concentrations to percent recovery on a per sample basis, where recovery of surrogate standard PCB 14 was used for mono-tri chlorinated biphenyls, d-PCB 65 was used for tetra-penta chlorinated biphenyls, PCB 166 was used for hexa-deca chlorinated biphenyls, and OH-PCB 159 was used for all OH-PCBs. PCB concentration is reported as per lipid weight (lw, Table S6) and fresh weight (fw, Table S7), where total lipids were determined from measured cholesterol and triglyceride values using an empirical equation from Bernert et al.20 OH-PCB concentrations are reported as per fresh weight (Table S6).

Quality Control

In this study, a full suite of QC was assessed using surrogate standards, field and instrument blanks, method blanks, and replicates of laboratory reference material (LRM) and Standard Reference Material (SRM) from National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST SRM 1589a: PCBs, Pesticides, PBDEs, and Dioxins/Furans in Human Serum).

A field blank study was undertaken to determine any PCB mass inadvertently contributed to the blood samples. Field staff used phlebotomy tubing and needle sets to puncture combusted glass vial reservoirs filled with 4% KCl (the same matrix used for method blanks) and dispensed the solution into blood collection tubes. Mimicking serum transfer, field staff pipetted the field blank solution from the tubes into glass vials equipped with Teflon-lined caps and returned them to the laboratory as is done for samples. After undergoing the same extraction and analysis methods as samples, it was determined that there was no significant mass contribution to serum samples from the field.

Instrument blanks consisting of vials of hexane were analyzed before and after the calibration standard and at the beginning and end of each sample batch. PCBs and OH-PCBs detected in instrument blanks were always below the limit of quantification (LOQ). The LRM consisted of homogenized archived human serum purchased from a Chicago blood bank and was analyzed for three target PCBs with every batch of samples to evaluate reproducibility. Analysis of congeners PCB 138, PCB 153, and PCB 180 in the LRM resulted in an average relative standard deviation of 16%. Replicates of NIST SRM 1589a were analyzed to evaluate accuracy and resulted in an average difference of 9% between our laboratory measurements and NIST certified and reference values. Detailed QC results are included in the Supporting Information.

Statistical Analysis

Limit of Quantification

Sum PCBs and OH-PCBs in the method blanks ranged from 0.47 ng to 3.5 ng per sample (2.3 ng per sample average) in the 6 batches used to determine the PCB LOQ and 0.030 to 0.14 ng per sample (0.092 ng per sample average) in the 9 batches used to determine the OH-PCB LOQ. Most PCB and all OH-PCB congeners were detected in the method blank as consistently low background noise, and the congener-specific LOQ was determined as the 95% confidence interval (mean + 2*SD) of the normally-distributed method blank data. Most of these congener LOQs were below 0.05 ng per sample (0.01 ng/g fw) but ranged as high as 0.13 ng per sample (0.03 ng/g fw) for PCBs 110+115 and 0.16 ng per sample (0.04 ng/g fw) for 4-OH-PCB 107. Congener-specific LOQs are shown in Tables S2–S3.

Variable levels of 10 PCB congeners as 5 chromatographic peaks (11, 52, 61+70+74+76, 90+101+113, and 95) were detected in the method blanks above background noise. The average relative standard deviation was much greater between batches (59–123%) than within (4–22%). For these congeners, masses detected in the blanks were subtracted from measured values in the samples. Then a separate 95% confidence interval (mean + 2*SD) was applied where mean was the value measured in the blank, and standard deviation was determined for each of the 5 congener groups from the separate analysis of multiple blanks in one batch. The separate blank analysis confirmed that although there was high batch-to-batch variation for these congeners in the blanks, within a batch each sample was affected similarly by contamination. Sample values for these congeners are reported as detect/non-detect only to reflect the increased likelihood of reporting false detections with blank subtraction.21 These congeners were not included in ΣPCB determination and reporting. Techniques for handling of data below the LOQ were explored, including imputation of LOQ/2 and LOQ/√2. Data were found to be significantly affected by these substitutions in a misleading way; therefore data below the LOQ were given a most conservative value of 0 for calculation of summary statistics and presentation of the data.

Statistical Tests

The concentration was first dichotomized at the threshold of the congener-specific LOQ (Tables S2–S3). Then the non-parametric Fisher’s exact test, Wilcoxon Signed Ranks test, and Wilcoxon Rank Sum test (α= 0.05) were applied to data from Columbus Junction and East Chicago separately. Mantel-Haenszel tests (α= 0.05) were employed for a combined analysis of these two cohorts. A parametric Tobit regression analysis was also employed. Instead of imputing the unknown values below LOQ, this method models the probability a value is below LOQ under the normality assumption. Since each subset of data appears to be skewed to the right, log transformation was applied to the data. This method was employed to determine statistically significant differences between concentrations of the 5 congeners detected in at least 30% of samples (83, 118, 129+137+138+163+164, 153+168, 180+193).22

RESULTS

Ninety-two PCB congeners as 62 unique chromatographic peaks and all 4 OH-PCB congeners were detected in the samples (Figure 1, Tables S6–S7) including commonly-detected congeners: 118, 138+129+137+163+164, 153+168, and 180+193 and dioxin-like congeners: 105, 118, 126, 156+157, 167, and 169. We also report the detection of PCB congeners 11 and 83, which to our knowledge have not been previously reported in human blood. PCBs 156+157, 187, 11, 113+90+101, and 95 were detected more frequently in East Chicago children than in Columbus Junction children, and PCBs 11 and 95 were detected more frequently in East Chicago mothers than Columbus Junction mothers (p<0.05). Considering all congeners together the total frequency of detections was statistically significantly higher in East Chicago than Columbus Junction in both mothers and children (p<0.05 and p<0.01, respectively).

Figure 1.

Detection frequency of each PCB and OH-PCB congener in our sample set of East Chicago and Columbus Junction residents (n=177). See Tables S6 and S7 for congener-specific data.

East Chicago and Columbus Junction residents had similar concentrations of total PCBs (Tables S6–S7, p = 0.6 and p = 0.3 for mothers and children, respectively) and OH-PCBs (Table S6, p = 0.3 and p = 0.8 for mothers and children, respectively). PCB concentrations in the overall sample set ranged from below detection to 210 ng/g lw with an outlier at 625 ng/g lw (a Columbus Junction mother). OH-PCB concentrations in the overall sample set ranged from below detection to 0.3 ng/g fw with an outlier at 1.2 ng/g fw (the same Columbus Junction mother). East Chicago and Columbus Junction residents also have similar levels of individual congeners in their serum (Table S6–S7).

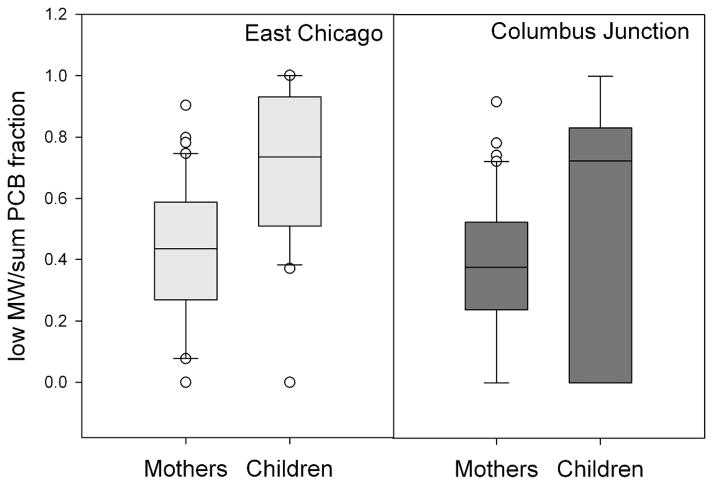

Mothers had higher levels of ΣPCBs (p<0.01) and ΣOH-PCBs (p<0.01) than their children, with the difference more pronounced for PCBs than OH-PCBs. The proportion of low- molecular weight PCBs was calculated for each individual as sum PCBs from homolog groups 1 through 5 divided by the sum of all PCBs. Interestingly, East Chicago children had a higher proportion of less chlorinated PCBs compared to their mothers (Figure 2, p < 0.01) than Columbus Junction children and their mothers.

Figure 2.

Fraction of low-molecular weight PCBs, defined as mono-penta CBs divided by total PCBs in mothers and children from East Chicago (left) and Columbus Junction (right). Data are plotted as box plots with the median indicated by the bold horizontal line, the two middle quartiles shown as polyhedrons above and below the median and the 95th percentiles shown as the horizontal lines connected by the dashed line. Outlier points are indicated by open circles.

Concentrations of OH-PCBs and their parent PCBs in each individual were compared to investigate whether a metabolic relationship exists. Grouping all participants together, sum OH-PCBs had a strong positive relationship with the sum of their parent PCBs (Figure 3). Investigating specific congeners (Figure 4), 4-OH-PCB 146 correlated with parent PCB 146 more strongly than parent PCBs 138 and 153, and 4-OH-PCB 187 correlated with parent PCB 187 more strongly than parent PCB 183, indicating possible preference for direct insertion. No such relationship was determined for 3′-OH-PCB 138. A relationship could not be tested for 4-OH-PCB 107 because PCB 107 was only detected in one participant.

Figure 3.

Fresh weight concentrations of sum OH-PCBs and sum of their precursor PCBs display a linear trend (R2 = 0.62, p < 0.0001). Each data point represents one participant. One leverage point, a mother with much higher concentrations than the other participants, was excluded. Participants with values <LOQ were excluded.

Figure 4.

Best fitting linear regressions between specific PCB parents and their OH-PCB metabolites in mothers and children: (a) 4-OH-PCB 107 with PCB 105 (R2 = 0.02) and PCB 118 (R2 = 0.11, p = 0.024); (b) 3′-OH-PCB 138 with PCB 138 (R2 = 0.13), and PCB 157 (R2 = 0.18); (c) 4-OH-PCB 146 with PCB 138 (R2 = 0.26, p < 0.0001), PCB 146 (R2 = 0.75, p = 0.0025), and PCB 153 (R2 = 0.39, p < 0.0001); (d) 4-OH-PCB 187 with PCB 183 (R2 = 0.27, p = 0.070) and PCB 187 (R2 = 0.47, p < 0.0001). One leverage point, a mother with much higher concentrations than the other participants, was removed from all 4 graphs. An outlier, a mother with a very high concentration of 4-OH-PCB 146 compared to the other metabolites was also removed from graph (c). Participants with values <LOQ were excluded; it was therefore not possible to determine correlations between PCB 107 and PCB 130 and their respective metabolites.

DISCUSSION

In this study we measured serum samples for all 209 PCBs and their 4 major metabolites. Congener-specific analysis is necessary for elucidating the role of environment on levels of PCBs in the blood as well as understanding the role of metabolism.

Sum PCB and sum OH-PCB levels measured in this study are similar to those found in populations not targeted for high dietary PCB consumption (Figures S2–S4). PCB levels measured in this study are similar to levels detected in serum from the U.S. general population23 and teachers in PCB-containing schools24 but are lower than in samples from Hudson River communities collected 2000–200225 and samples collected 1994–1999 from African-American women in Chicago.11 PCB levels measured here are also similar to Polish26 and Japanese27 mothers and women from Russia living in the vicinity of a chemical plant28 but are somewhat lower than levels measured in Belgium and Romania.12 PCB levels measured in this study are much lower than levels detected in populations consuming seafood29, 30 or food grown near a former PCB-producing plant in Eastern Slovakia.31 This result is likely because the participants eat very little seafood and food grown near PCB-contaminated IHSC.

OH-PCB levels measured in this study are similar to those detected in California mothers sampled before the PCB ban,32 Belgium and Romanian adults,12 Slovakian women living near a former PCB-producing plant,33 and Japanese breast cancer patients34 but are much lower than levels detected in populations consuming high amounts of seafood.29, 35, 36 It is interesting that the California and Slovakian cohorts had somewhat higher levels of PCBs but similar levels of OH-PCBs to this study’s participants. This result is probably because OH-PCBs can be excreted more readily than PCBs, and seafood was not a major part of the diets of this study’s participants.

The PCB 28, 105, and 153 concentrations reported in this study are compared to other studies (Figure 5). These three congeners were chosen for comparison because they are more commonly reported and they represent a range of low- to high-molecular weight congeners. PCB 28 is a lighter, more volatile congener, 105 is a dioxin-like congener, and PCB 153 is commonly associated with dietary PCB intake. For all three congeners, serum concentrations measured in subjects from East Chicago and Columbus Junction fall within the same range as the U.S. general population.23 Compared with older men and women living near the PCB-contaminated Hudson River,25 East Chicago and Columbus Junction subjects’ blood contained similar levels of PCB 28 and 105 but lower levels of PCB 153. Participants from East Chicago and Columbus Junction had similar blood levels of PCB 28, lower levels of PCB 105, and much lower levels of PCB 153 compared to men and women in the Russian arctic consuming high amounts of marine mammals.35 These congener-specific comparisons support the idea that PCB 153 in serum is an indicator of dietary PCB intake. Similar levels of PCBs 28 and 105 across the different cohort studies may reflect similar exposure to those PCBs, faster metabolism than higher-chlorinated PCBs, or a combination.

Figure 5.

Comparison of PCBs 28, PCB 105, and PCB 153 levels in units of nanogram per gram lipid weight in populations around the world, including this study. Population demographics and sample collection years are indicated in the figure. The published reports did not all use consistent measures of central tendency or range. These differences are indicated a–c, where a = min, median, max; b = mean & standard deviation; c = median. (ref 1),35 (ref 2),25 (ref 3).23 These references were chosen for comparison because they provided lipid weight concentration data for all three congeners and represented a variety of target populations.

Concentrations of individual OH-PCBs measured in this study were comparable with concentrations measured in other studies (Figure 6) including those from California mothers pre-PCB ban,32 Canadian Inuit,36 pregnant women near a former PCB-producing plant in Eastern Slovakia,33 Japanese breast cancer patients,34 and adults in Belgium and Romania.12 Pregnant women in the Faroe Islands with high blubber consumption had much higher levels of OH-PCBs in their blood than participants in this study.29 Differences among individual OH-PCB levels in the various cohorts are most obvious in 4-OH-PCB 187, the highest-chlorinated OH-PCB measured in this study, and least obvious in 3′-OH-PCB 138. This result may reflect different PCB exposures, different OH-PCB excretion rates, or a combination.

Figure 6.

Comparison of OH-PCB levels in units of nanogram per gram fresh weight in populations around the world, including this study. Population demographics and sample collection years are indicated in the figure. The published reports did not all use consistent measures of central tendency or range. These differences are indicated a–c, where a = median; b = min, median, max; c = 5%, median, 95%. (ref 1),29 (ref 2),32 (ref 3),34 (ref 4),33 (ref 5).12 These references were chosen for comparison because they provided data for all four congeners and represented a variety of target populations.

It is commonly believed that lifetime body burdens reflect the accumulation due to dietary exposure, yet the focus in the United States has recently shifted to include environmental exposures, particularly those arising from indoor air. Despite the expectation of a large environmental exposure difference, East Chicago and Columbus Junction participants in our study had only subtle differences in their PCB and OH-PCB blood levels. PCBs were detected in more East Chicago mothers and children than Columbus Junction mothers and children, and children from East Chicago were enriched in lower-molecular weight PCBs, but concentrations measured were similar between the two locations. Our findings of similar levels of PCBs in East Chicago and Columbus Junction residents are consistent with recently published studies from Fitzgerald et al. that measured PCBs in the serum from older residents living near General Electric facilities along the Hudson River. These residents had serum concentrations similar to residents living upstream of the contamination even though the ambient air concentrations varied significantly by proximity to PCB-contaminated areas.37 Their findings suggest that indoor air had a larger influence than ambient air on PCB serum concentrations. Further investigation found significant associations between PCB blood levels and indoor air levels, where duration of exposure was an important factor.25 Also highlighting the significance of PCBs in indoor air to PCB body burden, a pilot study from Herrick et al. of 18 teachers in PCB-containing schools found higher blood PCB concentrations than referent populations.24 Further research to clarify the role of inhalation exposure, particularly inhalation of indoor air, in our participants’ PCB blood levels is underway.

Our detection of PCB 11 in more than 60% of participants is important when considering environment as a source of PCB exposure. A volatile low-molecular weight PCB present in only a very small amount in one Aroclor,38 PCB 11 was recently determined to be an inadvertent byproduct of paint production and was measured in a wide variety of organic paint pigments from multiple manufacturers39 and in air.40 PCB 11 is neurotoxic.41

In contrast to PCB 11, PCB 83 was a minor component of Aroclors 1232, 1242, 1248, and 1254 and was not measured in paint pigment but was frequently detected in our participants. It is neither dioxin-like, nor considered a neurotoxin. PCB 118, another abundant congener in our participants, is a mono-ortho substituted dioxin-like congener that is both an AhR agonist42 and neurotoxic.41 Other abundant PCBs 28, 52, 95, 101, 138, 51, 180, and 187 have neurotoxic effects.41

Many studies have found correlation between age and PCBs in the blood,23, 34, 43 yet few studies have made observations about age and types of congeners. DeCaprio et al. found that the presence of patterns of low-persistence congeners was most apparent in younger individuals and was negatively correlated with age. Further, the pattern observed in serum that was most similar to a recently-measured air profile was more common in younger individuals.8 We discovered that East Chicago children are enriched in lower-molecular weight PCBs compared to their mothers. It is likely that children have not yet accumulated the upper-molecular weight PCBs, commonly associated with dietary PCB intake, that were measured in higher concentrations in their mothers. This evidence highlights the importance of environmental exposure to children’s blood PCB levels.

We found a strong relationship between levels of metabolites and their possible parent PCBs in the East Chicago and Columbus Junction participants (R2 = 0.62, p < 0.0001). A correlation was also shown by Dirtu et al. in samples from adults living in Belgium and Romania,12 Nomiyama et al. in samples from Japanese breast cancer patients,34 and Park et al. in samples from pregnant women from eastern Slovakia.33 Examining specific metabolites, our results indicate preference for direct insertion in the formation of 4-OH-PCB 146 and 4-OH-PCB 187 with no preference for the formation of 3′-OH-PCB 138. Nomiyama et al.34 found preference for direct insertion in the formation of 4-OH-PCB 187 and for NIH shift in the formation of 4-OH-PCB 107, 3′-OH-PCB 138, and 4-OH-PCB 146. In contrast, Dirtu et al.12 found no clear preference for one mechanism over the other, whereas Park et al.33 found preference for the NIH shift in formation of the metabolite 4-OH-PCB 146. The mixed findings from the small number of published studies measuring both OH-PCBs and their parent compounds points to the need for further investigation of PCB metabolism in humans.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the residents of East Chicago and the Columbus Junction area for their participation in the study. We thank Collin Just, Craig Just, Hans-Joachim Lehmler, Barb Mendenhall, Nancy Morales, A. Karin Norström, David Osterberg, and Carmen Owens for their contributions to participant enrollment, sample collection, and analysis. This study is supported by NIH P42 ES013661 and P30 ES005605, and a GAANN fellowship from the Department of Education (P200A09035011).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Method details, tables of congener-specific lipid weight and fresh weight PCB and OH-PCB concentrations, literature comparison figures. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Erickson MD, Kaley RG. Applications of polychlorinated biphenyls. Environ Sci Pollut R. 2011;18(2):135–151. doi: 10.1007/s11356-010-0392-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Letcher RJ, Klasson-Wehler E, Bergman A. Methyl sulfone and hydroxylated metabolites of polychlorinated biphenyls. In: Paasivirta J, editor. New Types of Persistent Halogenated Compounds. Vol. 3. Springer-Verlag: Berlin-Heidelberg; 2000. pp. 315–359. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robertson LW, Ludewig G. Polychlorinated Biphenyl (PCB) carcinogenicity with special emphasis on airborne PCBs. Gefahrst Reinhalt L. 2011;71(1–2):25–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boas M, Feldt-Rasmussen U, Main KM. Thyroid effects of endocrine disrupting chemicals. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2012;355(2):240–248. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2011.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grandjean P, Landrigan PJ. Developmental neurotoxicity of industrial chemicals. Lancet. 2006;368(9553):2167–2178. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69665-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pessah IN, Cherednichenko G, Lein PJ. Minding the calcium store: Ryanodine receptor activation as a convergent mechanism of PCB toxicity. Pharmacol Therapeut. 2010;125(2):260–285. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schantz SL, Widholm JJ, Rice DC. Effects of PCB exposure on neuropsychological function in children. Environ Health Persp. 2003;111(3):357–376. doi: 10.1289/ehp.5461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeCaprio AP, Johnson GW, Tarbell AM, Carpenter DO, Chiarenzelli JR, Morse GS, Santiago-Rivera AL, Schymura MJ, Environment ATF. Polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) exposure assessment by multivariate statistical analysis of serum congener profiles in an adult Native American population. Environ Res. 2005;98(3):284–302. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi AL, Levy JI, Dockery DW, Ryan LM, Tolbert PE, Altshul LM, Korrick SA. Does living near a superfund site contribute to higher polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) exposure? Environ Health Persp. 2006;114(7):1092–1098. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Costopoulou D, Vassiliadou I, Papadopoulos A, Makropoulos V, Leondiadis L. Levels of dioxins, furans and PCBs in human serum and milk of people living in Greece. Chemosphere. 2006;65(9):1462–1469. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2006.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGraw JE, Waller DP. Fish ingestion and congener specific polychlorinated biphenyl and p,p ′-dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene serum concentrations in a great lakes cohort of pregnant African American women. Environ Int. 2009;35(3):557–565. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dirtu AC, Jaspers VLB, Cernat R, Neels H, Covaci A. Distribution of PCBs, their hydroxylated metabolites, and other phenolic contaminants in human serum from two European countries. Environ Sci Technol. 2010;44(8):2876–2883. doi: 10.1021/es902149b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Status of restoration activities in Great Lakes areas of concern: A special report. International Joint Commission; 2003. http://www.ijc.org/php/publications/html/aoc_rep/english/report/pdfs/aoc_report-e.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martinez A, Wang K, Hornbuckle KC. Fate of PCB congeners in an industrial harbor of Lake Michigan. Environ Sci Technol. 2010;44(8):2803–2808. doi: 10.1021/es902911a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martinez A, Hornbuckle KC. Record of PCB congeners, sorbents and potential toxicity in core samples in Indiana Harbor and Ship Canal. Chemosphere. 2011;85(3):542–547. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2011.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hovander L, Athanasiadou M, Asplund L, Jensen S, Wehler EK. Extraction and cleanup methods for analysis of phenolic and neutral organohalogens in plasma. J Anal Toxicol. 2000;24(8):696–703. doi: 10.1093/jat/24.8.696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Method 1668C chlorinated biphenyl congeners in water, soil, sediment, biosolids, and tissue by HRGC/HRMS; EPA-820-R-10-005. US EPA; Washington, DC: 2010. http://water.epa.gov/scitech/methods/cwa/upload/M1668C_11June10-PCB_Congeners.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ueno D, Darling C, Alaee M, Campbell L, Pacepavicius G, Teixeira C, Muir D. Detection of hydroxylated polychlorinated biphenyls (OH-PCBs) in the abiotic environment: Surface water and precipitation from Ontario, Canada. Environ Sci Technol. 2007;41(6):1841–1848. doi: 10.1021/es061539l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bergman A, Klasson-Wehler E, Kuroki H. Selective retention of hydroxylated PCB metabolites in blood. Environ Health Persp. 1994;102(5):464–469. doi: 10.1289/ehp.94102464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bernert JT, Turner WE, Patterson DG, Needham LL. Calculation of serum “total lipid” concentrations for the adjustment of persistent organohalogen toxicant measurements in human samples. Chemosphere. 2007;68(5):824–831. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2007.02.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brodsky A. Exact calculation of probabilities of false positives and false negatives for low background counting. Health Phys. 1992;63:198–204. doi: 10.1097/00004032-199208000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lubin JH, Colt JS, Camann D, Davis S, Cerhan JR, Severson RK, Bernstein L, Hartge P. Epidemiologic evaluation of measurement data in the presence of detection limits. Environ Health Persp. 2004;112(17):1691–1696. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patterson DG, Wong LY, Turner WE, Caudill SP, Dipietro ES, McClure PC, Cash TP, Osterloh JD, Pirkle JL, Sampson EJ, Needham LL. Levels in the US population of those persistent organic pollutants (2003–2004) included in the Stockholm Convention or in other long-range transboundary air pollution agreements. Environ Sci Technol. 2009;43(4):1211–1218. doi: 10.1021/es801966w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herrick RF, Meeker JD, Altshul L. Serum PCB levels and congener profiles among teachers in PCB-containing schools: a pilot study. Environ Health. 2011;10 doi: 10.1186/1476-069x-10-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fitzgerald EF, Shrestha S, Palmer PM, Wilson LR, Belanger EE, Gomez MI, Cayo MR, Hwang SA. Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) in indoor air and in serum among older residents of upper Hudson River communities. Chemosphere. 2011;85(2):225–231. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2011.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jaraczewska K, Lulek J, Covaci A, Voorspoels S, Kaluba-Skotarczak A, Drews K, Schepens P. Distribution of polychlorinated biphenyls, organochlorine pesticides and polybrominated diphenyl ethers in human umbilical cord serum, maternal serum and milk from Wielkopolska region, Poland. Sci Total Environ. 2006;372(1):20–31. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2006.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Inoue K, Harada K, Takenaka K, Uehara S, Kono M, Shimizu T, Takasuga T, Senthilkumar K, Yamashita F, Koizumi A. Levels and concentration ratios of polychlorinated biphenyls and polybrominated diphenyl ethers in serum and breast milk in Japanese mothers. Environ Health Persp. 2006;114(8):1179–1185. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Humblet O, Sergeyev O, Altshul L, Korrick SA, Williams PL, Emond C, Birnbaum LS, Burns JS, Lee MM, Revich B, Shelepchikov A, Feshin D, Hauser R. Temporal trends in serum concentrations of polychlorinated dioxins, furans, and PCBs among adult women living in Chapaevsk, Russia: a longitudinal study from 2000 to 2009. Environ Health. 2011;10 doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-10-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fangstrom B, Athanasiadou M, Grandjean P, Weihe P, Bergman A. Hydroxylated PCB metabolites and PCBs in serum from pregnant Faroese women. Environ Health Persp. 2002;110(9):895–899. doi: 10.1289/ehp.110-1240989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sjodin A, Hagmar L, Klasson-Wehler E, Bjork J, Bergman A. Influence of the consumption of fatty Baltic Sea fish on plasma levels of halogenated environmental contaminants in Latvian and Swedish men. Environ Health Persp. 2000;108(11):1035–1041. doi: 10.1289/ehp.108-1240159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Petrik J, Drobna B, Pavuk M, Jursa S, Wimmerova S, Chovancova J. Serum PCBs and organochlorine pesticides in Slovakia: Age, gender, and residence as determinants of organochlorine concentrations. Chemosphere. 2006;65(3):410–418. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park JS, Petreas M, Cohn BA, Cirillo PM, Factor-Litvak P. Hydroxylated PCB metabolites (OH-PCBs) in archived serum from 1950–60s California mothers: A pilot study. Environ Int. 2009;35(6):937–942. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Park JS, Linderholm L, Charles MJ, Athanasiadou M, Petrik J, Kocan A, Drobna B, Trnovec T, Bergman A, Hertz-Picciotto I. Polychlorinated biphenyls and their hydroxylated metabolites (OH-PCBs) in pregnant women from eastern Slovakia. Environ Health Persp. 2007;115(1):20–27. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nomiyama K, Yonehara T, Yonemura S, Yamamoto M, Koriyama C, Akiba S, Shinohara R, Koga M. Determination and characterization of hydroxylated polychlorinated biphenyls (OH-PCBs) in serum and adipose tissue of Japanese women diagnosed with breast cancer. Environ Sci Technol. 2010;44(8):2890–2896. doi: 10.1021/es9012432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sandanger TM, Dumas P, Berger U, Burkow IC. Analysis of HO-PCBs and PCP in blood plasma from individuals with high PCB exposure living on the Chukotka Peninsula in the Russian Arctic. J Environ Monit. 2004;6(9):758–765. doi: 10.1039/b401999g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sandau CD, Ayotte P, Dewailly E, Duffe J, Norstrom RJ. Analysis of hydroxylated metabolites of PCBs (OH-PCBs) and other chlorinated phenolic compounds in whole blood from Canadian Inuit. Environ Health Persp. 2000;108(7):611–616. doi: 10.1289/ehp.00108611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fitzgerald EF, Belanger EE, Gomez MI, Hwang SA, Jansing RL, Hicks HE. Environmental exposures to polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) among older residents of upper Hudson River communities. Environ Res. 2007;104(3):352–360. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2007.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Frame GM, Cochran JW, Bowadt SS. Complete PCB congener distributions for 17 aroclor mixtures determined by 3 HRGC systems optimized for comprehensive, quantitative, congener-specific analysis. J High Res Chrom. 1996;19(12):657–668. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hu DF, Hornbuckle KC. Inadvertent polychlorinated biphenyls in commercial paint pigments. Environ Sci Technol. 2010;44(8):2822–2827. doi: 10.1021/es902413k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hu DF, Lehmler HJ, Martinez A, Wang K, Hornbuckle KC. Atmospheric PCB congeners across Chicago. Atmos Environ. 2010;44(12):1550–1557. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Simon T, Britt JK, James RC. Development of a neurotoxic equivalence scheme of relative potency for assessing the risk of PCB mixtures. Regul Toxicol Pharm. 2007;48(2):148–170. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van den Berg M, Birnbaum LS, Denison M, De Vito M, Farland W, Feeley M, Fiedler H, Hakansson H, Hanberg A, Haws L, Rose M, Safe S, Schrenk D, Tohyama C, Tritscher A, Tuomisto J, Tysklind M, Walker N, Peterson RE. The 2005 World Health Organization reevaluation of human and mammalian toxic equivalency factors for dioxins and dioxin-like compounds. Toxicol Sci. 2006;93(2):223–241. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfl055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Humblet O, Williams PL, Korrick SA, Sergeyev O, Emond C, Birnbaum LS, Burns JS, Altshul L, Patterson DG, Turner WE, Lee MM, Revich B, Hauser R. Predictors of serum dioxin, furan, and PCB concentrations among women from Chapaevsk, Russia. Environ Sci Technol. 2010;44(14):5633–5640. doi: 10.1021/es100976j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.