Abstract

Neurokinin 1 (NK1) encodes full-length (NK1-FL) and truncated (NK1-Tr) receptors, with distinct 3′ UTR. NK1-Tr exerts oncogenic functions and is increased in breast cancer (BC). Enhanced transcription of NK1 resulted in higher level of NK1-Tr. The 3′ UTR of these two transcripts are distinct with NK1-Tr terminating at a premature stop codon. NK1-Tr mRNA gained an advantage over NK1-FL with regards to translation. This is due to the ability of miR519B to interact with sequences within the 3′ UTR of NK1-FL, but not NK1-Tr since the corresponding region is omitted. MiR519b suppressed the translation of NK1-FL in T47D and MDA-MB-231 resulting increased NK1-Tr protein. Cytokines can induce the transcription of NK1. However, our studies indicated that translation appeared to be independent of cytokine production by the BC cells (BCCs). This suggested that transcription and translation of NK1 might be independent. The findings were validated in vivo. MiR-519b suppressed the growth of MDA-MB-231 in 7/10 nude BALB/c. In total, increased NK1-Tr in BCCs is due to enhanced transcription and suppressed translation of NK1-FL by miR-519b to reduced tumor growth. In summary, we report on miRNA as a method to further regulate the expression of a spiced variant to promote oncogenesis. In addition, the findings have implications for therapy with NK1 antagonists. The oncogenic effect of NK1-Tr must be considered to improve the efficacy of current drugs to NK1.

Keywords: Neurokinin-1, miR519b, breast cancer, translation, transcription

Introduction

Despite early detection programs and increased awareness, breast cancer (BC) remains a clinical dilemma [1]. The neurokinin-1 (NK1) receptor and one of the genes that encodes its ligands, TAC1, have been showed to exert oncogenic functions [2–6]. NK1-Tr facilitated the aggressiveness of tumors and seems to be a biomarker of transformation in colitis [5,7].

A single NK1 gene generates a full length (NK1-FL) and a truncated (NK1-Tr) receptor [8]. NK1-Tr lacks 100 residues in the carboxyl/intracytoplasmic end of the molecule [8]. The 3′UTR of the two NK1 subtypes are distinct (Fig. S1). NK1-Tr is formed by a failed splicing between Exons 4 and 5, resulting in termination at a premature stop codon at the beginning of Exon 5 [9].

NK1 subtypes are 7-transmembrane, G-protein coupled receptors that interact with different binding affinities to the tachykinin family of peptides [10,11]. The major tachykinin peptide, substance P, has binding preference for NK1-FL and reduced binding affinity for NK1-Tr [8]. These differences correlated with distinct intracellular signaling by the NK subtypes [12]. NK1-Tr activation is generally prolonged. It is possible that the prolonged activation might be due to inefficient receptor internalization. This could occur because the missing cytoplasmic region of NK1-Tr is unavailable to interact with β-arrestin, which facilitates internalization [13].

NK1-Tr induces the production of cytokines in BC cells (BCCs) [5]. The cytokines can stimulate the BCCs through autocrine and paracrine mechanisms to activate NFκB activation increase the transcription of NK1, [14,15]. Our previous ex vivo studies with stable transfectants of NK1 subtypes in non-tumorigenic breast epithelial cells validated an oncogenic role for NK1-Tr [5]. This led to the present studies to examine the mechanism by which NK1 subtypes are expressed at the transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels. This study reported on the generation of NK1-Tr and NK1-FL when transcription is increased. Despite the presence of both transcripts, only NK1-Tr was highly expressed at the level of protein. This was explained by the differences in the 3′ UTR of the two transcripts. The omitted 3′ UTR of NK1-Tr could not interact with microRNA (miR-519b) to suppress its translation whereas NK1-FL was suppressed by miR519b.

This study used a modified non-radioactive method to analyze the transcriptional rate of NK1 and then studied the roles of the oncomirs, miR-519b and miR-609, on the translation of NK1 subtypes [16,17]. Since NK1 antagonists are widely available and show promise as anticancer therapy [18] this report opens up a discussion on the efficacy of the antagonists if tumor is mediated by the truncated form. A model system was applied to understand the role of transcription. This was followed by studies on translational control in BCCs. We reported on miR-519b-mediated suppression of NK1-FL. These findings were validated in vivo and are discussed in the context of miR-519b acting as an anti-proliferative agent through its ability to bind the RNA-binding protein HuR [19]. The role of miR519b in suppressing a spliced variant to promote oncogenesis is discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

See supplemental section.

Cell Lines

Fibroblast 1502 and breast cancer cell (BCC) lines, T47D and MDA-MB-231, were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA) and expanded as per manufacturer’s instructions.

BM Stromal Cells

Stromal cells were cultured from BM aspirates of healthy individuals as described previously [20]. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey-Newark Campus. At confluence, the adherent cells were passaged five times in α-MEM (Sigma). The cells, at passage 5 were >99% for anti-smooth muscle actin (Carpinteria, CA).

NK1 probes

The expression vector (pSG5-NK1) with the full-length coding region (1.2 kb) of NK1 was previously described [5]. The 1.2 kb fragment served as a template to prepare DNA fragments to detect NK1-FL and NK1-Tr mRNAs. We first excised the coding region with EcoR1 and then digested with Alu1 to acquire 0.9 Kb and 0.3 Kb fragments (Fig. S2A). The 0.3 Kb fragment detected NK1-FL (Fig. S2B). The 0.9 Kb fragment (Fig. S2A) was further digested with BmpII into 0.6 and 0.3 Kb fragments. The latter detected total NK1 by its ability to hybrize with both NK1 subtypes (Fig. S2B).

Non-radioactive nuclear run-on assay

Nuclei were isolated from unstimulated BCCs and fibroblast 1502, stimulated with 10 ng/mL of IL-1 α for 6, 12 and 16 h or vehicle (PBS). New transcripts were collected from the nuclei as described [21]. The transcripts were quantified for NK1 subtypes in a fluorometric method as described [16]. Equal amounts (50 ng) of mRNA and cDNA probes in 20 μL were annealed for 10 min at 37°C. After this, 50 μL YoYo-1 solution, at 1/1000 dilution in 10 mM Tris/1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0, was added to the mix. After 5 min at room temperature, the samples were analyzed for incorporated YoYo-1 on a Victor 3V multiwall plate reader fluorometer (Perkin Elmer, Watham, MA). Since the probe for NK1-Tr detected total transcripts, its level was calculated by subtracting the fluorescence intensity of NK1-FL from the intensity of NK1-Tr (Fig. S2B).

Real-time RT-PCR for miRNAs

The levels of miRNA-519b and -609 were analyzed by real-time RT-PCR, as described [22]. Total miRNA was extracted with a miRNA isolation kit from Invitrogen. The miRNA was reverse-transcribed and then amplified with the mirVana qRT-PCR miRNA Detection Kit (Invitrogen). The primers were purchased from Ambion. PCRs were presented in reference to the internal control, U6. The relative expression was calculated by determining the ΔCt, which was obtaining by subtracting the Ct value of the gene of reference from the Ct of the internal control and then presented as 2ΔCt.

Real-time PCR for NK1 subtypes

RNA was extracted with the RNeasy Mini Kit from (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and then analyzed as in real-time PCR 200 ng cDNA on the 7300 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The analyses were performed with an initial incubation of 50°C for 2 min followed by 95°C for 2 min. After this, the cycling conditions were as follows: 94°C for 15 sec and 60°C for 45 sec, for 40 cycles. Primer sequences were specific for NK1-Tr and NK1-FL: NK1-Tr, (F) 5'-AAC CCC ATG AGC TCT CC-3', (R) 5'-CCA TTC CTG GAT GGT GAT-3'; NK1-FL, (F) 5'-ACC CTC ATG CTG TGT GAC 3', (R) 5'-GGC TCC AGG AAA ATG AGT-3'

Vectors

Nested PCR cloned the 3′ UTR of NK1 (Accession no. M84425), which was ligated downstream of the luciferase gene in pMIR-REPORT (Ambion, Austin, Tx). The template was prepared by extracting total RNA from T47D. The outer forward (F1) and reverse (R1) primers were 5′-GAC TCC AAG ACC ATG ACA GAG AGC-3′ and 5′-CAT CCT GAA ATG AGC ACT CGC ATG-3′, respectively. The inner forward (F2) primer contains a SpeI linker: 5′-GTA CTA GTG CCA CAG GGC CTT TGG CAG GTG CAG CCC CCA C-3′. The reverse primer (R2) contains a HindIII linker: 5′-GCA AGC TTC ATC CTG AAA TGA GCA CTC GCA TGC AGC CAA AG-3′. PCR product from the amplification of F2/R2 was cloned into pCR2.1 (Invitrogen) and then sequenced at the Molecular Core Facility at New Jersey Medical School (Newark, NJ). The DNA insert was excised with SpeI and HindIII and then subcloned into pMIR-REPORT, hereafter referred as pMIR/NK1-SR. The insert was sequenced to ensure accuracy.

Transfection and Reporter Gene Assay

The 3′ UTR of NK1 mRNA was analyzed for candidate miRNAs with miRanda target prediction software (www.microrna.org). Mir-609 and mir-519b was predicted as candidate miRs for the 3′ UTR of NK1 transcripts. These two miRNAs were validated by co-transfecting the pre-miRs or negative control vector and pMIR/NK1-UTR-SR reporter gene vector (described above). The negative control pre-miR, pre-mir-609 and pre-mir-519b were purchased from Ambion.

T47D and MDA-MB-231, at 50% confluence, were co-transfected with pMIR-R/NK1-SR and pre-miR-609, pre-miR-519b or negative control pre-miR. Normalization was achieved by co-transfecting with pMIR-β-gal (Ambion). After 48 h lysates were prepared as for described [23] and then quantitated for total protein with the DC protein assay kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Extracts were analyzed for luciferase activity using the Luciferase Assay System (Promega, Madison, WI) and for β-gal with the detection kit II (BD Clontech, Palo Alto, CA).

Western blot

Cytokine microarray

MDA-MB-231 was transfected with control pre-miR or pre-miR-519b. At 24 h after transfection the culture media were analyzed with human cytokine protein array 3 (Ray Biotech, Inc., Norcross, GA), as described [5]. Briefly, membranes were incubated for 1 h with culture supernatants and then incubated consecutively with biotin-conjugated anti-cytokines and HRP-streptavidin followed by chemiluminescence detection. Background was subtracted in analyses with fresh culture media.

Animal

The use of animals was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, Newark Campus. Female nude BALB/c (4 weeks) were obtained from Harlan Laboratories (Indianapolis, IN) and housed in the barrier room at an AAALAC-accredited facility. After two weeks, 106 MDA-MB-231, untransfected or, transfected with control anti-miR or anti-miR-519 sequences, were resuspended with equal volumes of matrigel in 0.2 mL, subcutaneously in the dorsal flanks of mice. At 3-day intervals, beginning at day 7 the mice were examined for tumor growth and detectable tumors were measured in two dimensions with a caliper. Tumor volume was calculated using the following formula: V = πr2h, where r = radius and h = height.

Statistical analyses

Data were analyzed using analysis of variance and Tukey-Kramer multiple comparisons test. A p value <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Optimization of induced NK1 subtypes in healthy fibroblasts

We first determined if the differences in NK1 subtypes could be explained at the level of transcription and, if an increase in transcription could produce NK1-Tr. Transcriptional rate was studied with nuclear run-on assays. The findings were compared with steady state mRNA by real time RT-PCR using primers specific for each NK1 subtype (Fig. S1).

We optimized the non-radioactive nuclear run-on method with Fibroblast 1502 to prevent confounds that could occur in malignant cells in the transcriptional rate of NK1. The basis for non-transformation of fibroblast 1502 is the cell line’s ability stop proliferation upon contact with each other and with no evidence of foci formation. Since the expression of NK1 in non-transformed cells requires stimulation, we induced its transcription with IL-1α in the fibroblast [14]. The level of NK1-Tr was obtained by subtracting the value of NK1-FL from the total (NK1-FL+NK1-Tr) (Figure S2). Dose-response and time-course studies indicated 10 ng/mL IL-1α and 16 h as optimal in the generation of NK1-Tr (Fig. S3). Using the optimal conditions, fibroblasts containing vehicle showed low to undetectable transcripts (Fig. 1A) whereas IL-1α caused significant (p<0.001) increases for both NK1 types (Fig. 1A). However, there was significantly (p<0.001) more NK1-Tr than NK1-FL (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1. Nuclear run-on and Real-time RT-PCR for NK1 subtypes.

(A) A non-radioactive method quantitated NK1-FL and NK-Tr. Fibroblast 1502 was stimulated with 10 ng/mL IL-1α or vehicle for 8 h. Nuclei were isolated and total RNA collected within a 24 h period for hybridization with cDNA probes and fluorochrome YoYo-1. The incorporated YoYo-1 was detected with a fluorometer. The results are presented as fluorescence intensity, mean±SD, n=7. (B) Real time was performed with primers that can discriminate NK1-FL and NK1-Tr with cDNA from IL-1α-stimulated fibroblasts. Control contained vehicle (PBS). The lowest value was normalized as 1 and the other experimental points were presented as relative fold change (mean±SD, n=4) as described [22].

* p<0.05 vs. IL-1α stimulated cells; ** p<0.05 vs. NK1-Tr; *** p<0.05 vs. NK1-Tr

In order to study steady state NK1 mRNA, we repeated the stimulation in Fig. 1A and then analyzed the cells for NK1-FL and NK1-Tr mRNA by real-time PCR. The lowest values were assigned 1 and the other experimental points were presented as the relative fold change as described [22]. NK1-FL was significantly (p<0.01) increased as compared to NK1-Tr (Fig. 1B). In summary, this section showed an increase in NK1-Tr when transcription was enhanced. However, at the level of steady state mRNA, NK1-FL was increased. The disparity between NK1 transcription and the level of steady state mRNA is discussed, second to last paragraph in the respective section.

IL-1α stimulation led to an increase in NK1-Tr (Fig. 1), which has been shown to have oncogenic property [5,7]. We therefore asked if IL-1 stimulation during the experimental condition of 16 h transformed the fibroblasts. Since the studies in Figure 1 used a cell line, which is immortalized, the line cannot be truly normal. We therefore used primary BM stroma, which are fibroblasts and then repeated the stimulation as above. After 16 h, we removed the IL-1α by repeated washes and then reincubated for one week. At this time, the stroma showed contact-dependent proliferation and failed to form foci, indicating no evidence of transformation. It is possible that the relatively short time period of IL-1α exposure was insufficient to induce transformation.

Transcriptional rate and steady state mRNA for NK1 subtypes in BCCs

The high expression of NK1-Tr in MDA-MB-231 and T47D mediated their proliferation [5]. Non-tumorigenic mammary epithelial cells do not express NK1 unless induced, similar to what was observed for Fibroblast 1502 (Fig. 1). Thus, this study will not compare the BCCs with non-transformed cells since the purpose of the study was to understand why BCCs have higher levels of NK1-Tr and to determine the level at which the regulation occurred: transcription vs. post-transcription.

Transcriptional rate was studied with T47D and MDA-MB-231 using nuclear run-on studies as for Fig. 1A. There was significantly (p<0.05) higher levels of NK-1Tr as compared to NK1-FL (Fig. 2A). This correlated with an increase in NK1-Tr protein, by western blots and whole cell extracts. The anti-NK1 detected both subtypes (Fig. 2B). The normalized band densities showed significant increase in NK1-Tr (Fig. 2C). In summary, this section describes studies showing higher levels of NK1-Tr mRNA and its corresponding protein in BCCs. These increases appeared to be caused by an increase in NK1 transcription.

Fig. 2. Nuclear run-on, real-time RT-PCR and western blots for NK1 subtypes in BCCs.

(A) Unstimulated T47D and MDA-MB-231 were studied for NK1-FL and NK1-Tr using the nuclear run-on assay as for Fig. 1A. The results are presented as the mean fluorescence intensity±SD, n=4. (B) Total cell extracts from T47D and MDA-MB-231 were studied for NK1 subtypes by western blots. (C) Normalized band densities for NK1-FL and NK1-Tr, n=3±SD. (D) Real-time was performed for NK1-FL and NK1-Tr as for Figure 1B. The lowest value was normalized as 1 and the other experimental points were presented as relative fold change (mean±SD, n=4) as for Fig. 1D.

* p<0.05 vs. NK1-FL

Since NK1 is constitutively expressed in BCCs [5], we determined if the steady state levels of NK1 subtypes correlated with transcription. Real-time RT-PCR with total RNA from T47D and MDA-MB-231 showed a significant (p<0.05) increase in NK1-FL as compared to NK1-Tr (Fig. 2D). The results were unexpected as they contrasted the levels at transcription (Fig. 2A). In summary, this section showed an accumulation of NK1-FL in BCCs whereas there was higher production of NK1-Tr transcripts. As for Fig. 1, the similar disparity between NK1 transcription and the level of steady state mRNA is discussed, second to last paragraph in the respective section.

Levels of miR-609 and miR-519b in BCCs

Despite higher level of steady state NK1-FL mRNA, there was an increase in NK1-Tr protein (Figs 2B and 2C). We therefore asked if this could be explained by translational repression of NK1-FL. We focused on miRNAs due to their role in repressing translation. Computer analyses (miRanda alogorithm) of the 3′ UTR of NK1 identified miR-609 and miR-519b as potential candidates for binding to the 3′UTR of NK1-FL but not NK1-Tr because the regions were omitted in its 3′UTR (Figs 3A and S1). Additional support for examining these two miRNAs was conservation among species, highest scores in the analyses and multiple predicted sites. The relative expression of the normalized gene in real-time RT-PCR for miR519b and miR-609 in MDA-MB-231 and T47D indicated higher levels of miR-519b but undetectable miR-609 (Ct>40) (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3. MiR519b and miR609 levels in BCCs.

(A) Shown are the 3′ UTR of NK1 (Tr and Fl) and the relative positions of miR519 and miR609. (B) Real-time PCR was performed for miR-519b and miR-609 with cDNA from T47D and MDA-MB-231. The data are presented as the relative fold change (mean±SD, n=5).

Effects of miR-609 and miR-519b on reporter gene activity with NK1 3′UTR

Despite undetectable miR-609 in BCCs (Fig. 3B), we studied its function with a heterologous reporter gene system containing the 3′UTR of NK1 (pMIR-NK1-SR, Fig. S4). The vector was previously described [22]. MDA-MB-231 and T47D were co-transfected with pMIR-NK1-SR and, pre-miR-609, pre-miR-519b or control pre-miRs. After 48 h, the cell extracts were analyzed for luciferase level. In both cell lines, transfection with each pre-miR showed significant (p<0.05) decreases in luciferase levels; with no evidence of additive or synergistic effect (Figs 4A and 4B). Parallel transfections with control pre-miR were similar to untransfected cells and the values were therefore plotted on the same experimental point (open bar).

Fig. 4. Effects on reporter gene activity by pre-miR-519b and -miR609.

MDA-MB-231 and T47D were co-transfected with pMIR/NK1-SR (Figure S4) and pre-miR-519b (A) or pre-miR-609 (B). After 48 h luciferase activities were quantitated with whole cell extracts and the results are presented as the mean±SD, n=6. * p<0.05 vs. pre-miR-transfectants. (C) BCCs were transfected with pre-miR519b and/or anti-miR519b. Controls were transfected with control pre-miR. After 48 h, real-time PCR was performed for pre-miR519b and the data presented as fold change (mean±SD, n=4) of the lowest value, which was assigned a value of 1. (D) The studies in A and B were repeated, except with co-transfection with pre- and/or anti-miR519b. Parallel cultures were transfected with control pre-miR. After 48 h, luciferase activities were quantitated and the results are presented as for A and B’ (mean±SD, n=4).

Since miR519b level was increased in BCCs (Fig. 3B), its ability to suppress luciferase indicated its functional significance in suppressing the 3′UTR of NK1-FL (Figs 4A and 4B). We next verified that the effect of transfected pre-miR519b on luciferase level was not due to degradation of the pre-miR. We transfected BCCs with pre-miR519b and after 48 h, we performed real time PCR for miR519b. The Ct values were normalized to the control U6. The lowest value was assigned 1 and the other values were calculated as fold change. The level of miR519b was ~15 fold increase in the transfectants (Fig. 4C, open bar). This value was reduced by 50% when the pre-miR was co-transfected with anti-miR519b (Fig. 4C, left diagonal bar), indicating that the transfected pre-miRs were not degraded. We next evaluated the specificity of miR-519b by co-transfecting the reporter gene with pre- and anti-miR519b. Anti-miR519b significantly (p<0.05) blunted the ability of pre-miR519b to suppress luciferase activity (Fig. 4D), supporting the specificity of miR-519b to suppress the translation of luciferase.

Effects of miR-609 and miR-519b on the translation of NK1 subtypes

Despite undetectable miR-609 in BCCs (Fig. 3B), it was functionally, based on its ability to suppress luciferase (Figs 4A and 4B). We therefore asked if miR-609 and miR519b can suppress the translation of endogenous NK1-FL. The studies used MDA-MB-231 since both NK1-FL and NK1-Tr were co-expressed in these cells (Fig. 2B). MDA-MB-231 was transfected with different amounts of pre-miR-609, pre-miR-519b or control pre-miR and then analyzed for NK1 subtypes by western blots with whole cell extracts. The results are shown for 10 nM of control and the pre-miR. Control pre-miR showed bands for NK1-FL and NK1-Tr (Fig. 5A). The results of the control were similar to the transfectants, showing no significant different (p>0.05) (Fig. 5A). The normalized densities of the bands were presented as the ratio of NK1-Tr/NK1-FL. Pre-miR519b showed no significant (p<0.05) increase in NK1-Tr:NK1-FL ratio as compared to the control pre-miR (Fig. 5B). We attributed these results to the already increase in miR-519b in the BCC (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 5. MiRNAs in the expression of NK1 subtypes.

(A) MDA-MB-231 was transfected with pre-miR609, -miR519b or control pre-miR. After 24 h, whole cell extracts were studied for NK1 subtypes by western blots. The membranes were stripped and reprobed with anti-β-actin. (B) The band densities in `A’ were normalized and the data from three different western blots are presented as the ratio of NK1-Tr/NK1-FL, mean±SD. MDA-MB-231 and T47D were transfected with anti-miR519b and then analyzed as for `A’. (C) MDA-MB-231 and T47D were transfected with anti-miR519b and then analyzed as for `A’. (D) The band densities in `B’ were normalized and the data from three different western blots are presented as for `B’.

* p>0.05 vs. control; *** p<0.01 vs. anti-miR519

To validated a role for pre-miR519b in a corollary experiment in which we knockdown miR-519b in MDA-MB-231 with anti-miR-519b or control anti-miR. Dose-response studies indicated 10 nM pre-miR as optimum. Western blot indicated that knockdown of miR-519b promoted the translation of NK1-FL (Figs 5C). The normalized band density indicated significant (p<0.01) decrease in the ratio of NK1-Tr/NK1-FL (Fig. 5D). Together, this section describes a suppressive role for miR-519b in the translation of NK1-FL.

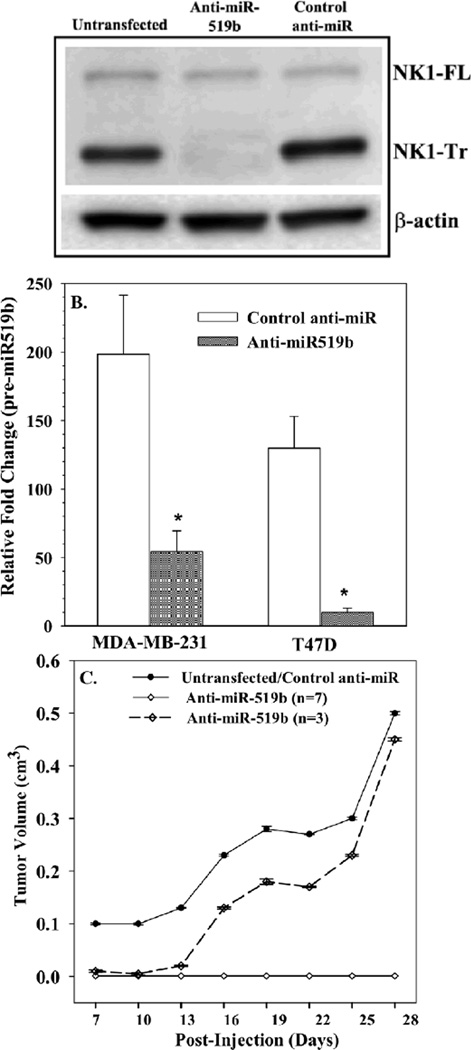

Effects of anti-miR519 on tumor formation in nude BALB/c

NK1-Tr has been reported to increase BCC proliferation [5]. Since miR-519b can suppress the translation of NK1-FL to increase NK1-Tr (Fig. 5), we asked if, increasing NK1-FL through knockdown of miR-519b, could reduce the growth of MDA-MB-231, in vivo. MDAMB-231 (106) was untransfected or, transfected with control anti-miR or anti-miR-519b. The transfection efficiency was determined after 48 h by western blot for NK1 subtypes and by real time PCR for pre-miR-519b (Figs 6A and 6B). Although the band for NK1-FL was less dense (Fig. 6A) than the corresponding studies (Fig. 5C), the final outcome was comparable with predominance of NK1-FL with the ratios of NK1-Tr/NK1-FL as ~5. The transfectants were injected subcutaneously in the dorsal flank of female nude BALB/c, as described [24].

Fig. 6. Effects of anti-miR-519b on tumor growth.

MDA-MB-231 cells were transfected with anti-miR519b or control anti-miR. The transfectants were validated by western blot for NK1-Tr (A) and real-time PCR for pre-miR519b (B). (C) Nude BALB/c (n=10) were injected with 106 cells, subcutaneously in the dorsal flank. The tumor volumes, presented as mean±SD. The experimental group (anti-miR519b) were plotted as those with no palpable tumor (n=7) and those with tumor growth (n=3).

*p<0.05 vs. control anti-miR

Beginning at day 7, the tumor volumes were increased in 10/10 mice with untransfected cells, 9/10 with control anti-miR and 3/10 mice with anti-miR-519b. The tumor volumes were plotted as a function of days, post-injection (Fig. 6C). Non-transfectants and control anti-miR transfectants showed similar tumor growth and were plotted together. Since 3/10 mice, transfected with anti-miR519, we plotted these findings together (Fig. 6C) and combined the 7/10 mice that showed no tumor growth in a separate plot. At ~0.5 cm3 the experiment was stopped due to humane end point. There was significant (p<0.05) reduction by anti-miR-519. In summary, knockdown of miR-519 reduced the growth of MDA-MB-231 in vivo.

Cytokine production in anti-miR519b transfectants

Since knockdown of miR-519b caused a reduction in tumor growth (Fig. 6), we asked if this could be explained by a decrease in cytokine production. Decrease in cytokine production would have an impact on the transcriptional rate of NK1 and this might account for reduced tumor growth [14]. We therefore transfected MDA-MB-231 with control anti-miR or anti-miR-519b and after 24 h, the cell culture media were analyzed with cytokine protein arrays (Fig. S5). As expected, control miR showed high expression of multiple cytokines [5]. There was no change in anti-miR-519b transfectants (Fig. S5).

The data are presented as images of the membranes, which showed no change in the 42 cytokines, excluding the controls. Since NK1 has been shown to be induced by cytokines with a key role for NFκB, it was important to determine if miR-519B alter cytokine production because if miR519b changed the production of cytokines this would indicate that miR does not only suppress the translation of NK1-FL but also affect its transcription. Since there was no change in the cytokines, this indicated that miR-519b acts at the level of translation and likely does not affect transcription.

DISCUSSION

Here we report on mechanisms that partly explain the predominance of NK1-Tr in BCCs. An increase in the transcriptional rate of NK1 resulted in both NK1-FL and NK1-Tr mRNA but higher levels of NK1-Tr (Fig. 1). At the level of protein both NK1 subtypes are expressed in BCCs [5]. This study confirmed that the rate of transcription produces higher levels of NK1-Tr (Figs 1A and 2A). Although both subtypes are translated, this study showed significant suppression in the translation of NK1-FL by miR-519b (Fig. 5). We deduced that this can be partly explained by the 300 nt sequence within the 3′ UTR in NK1-FL, which is absent in the 3′ UTR of NK1-Tr (Fig. 3A). MiR-519b can bind to the 3′ UTR of NK1-FL to suppress its translation, resulting in higher level of NK1-Tr protein.

The NK1-Tr transcript was offered an advantage due to the ability of miR-519b to suppress the translation of only NK1-FL (Figs 3–6). Since NK1-Tr is associated with BCCs and colitis-associated cancer [5,7], the premature stop codon in NK1-Tr transcript could be added to the list of cancers with premature stop codon for diagnosis and prognosis [25]. Although this study did not prove that NK1-Tr is directly responsible for the seeming premature halting of transcription, the nuclear run-on assay suggested this to be the case. Answer to this question requires follow-up studies to prove that transcriptional increases use the premature stop codon to produce NK1-Tr transcripts. If decreasing the transcriptional rate can reduce NK1-Tr this could be a method of therapeutic intervention. Indeed, cytokines can increase NK1 transcription [14,15]. More importantly, BCCs produce substance P, which is the ligand for NK1 [6]. Furthermore, substance P can induce the production of cytokines to regulate NK1 expression [5]. Since NK1 antagonists are available, these drugs could be used to slow the transcriptional rate of NK1 as a method of BC treatment [18,26]. The findings in this report might not be limited to BC since NK1 has been linked to the development of various cancers [18,27–30].

The reports on NK1 in cancer lack studies that dissect NK1-FL and NK1-Tr. It is necessary to determine how the antagonists affect each subtype of receptor for preclinical studies. It would be important to examine how the antagonist affect each subtype of NK1 receptors because they exert different effects on tumor proliferation [5]. The findings in this study, combined with others [5], indicate that an efficient small molecule of NK1 antagonist will be one that blocks the function of NK1-Tr rather than NK1-FL.

Although the data indicate that miR519b acts directly on the 3′UTR of NK1, other mechanisms could be involved. MiR-519b can suppress the translation of the RNA-binding protein HuR [19]. A decrease in HuR will induce instability of NK1-FL, thereby providing an advantage to NK1-Tr, which has a relatively short 3′ UTR. These arguments are important to clarify how steady state mRNA for NK1 subtypes are regulated. Unlike transcriptional rate where NK1-Tr levels are increased, it is reduced at the steady state level (Figs 1B and 2D).

Cytokines can induce the transcription of the NK1 gene [14] as seen in this report with IL-1α (Fig. 1A). We have reported on an increase in NK1-Tr by cytokines in BCCs, through autocrine stimulation [5]. In this study, miR-519b appears to be limited to translational control because its knockdown in MDA-MB-231 did change the cytokine profile (Fig. 7A). We therefore deduce that transcriptional and translational controls are independent and that miR-519b does not require a change in cytokine production to suppress the translation of NK1-Tr.

Fig. 7. Overall summary.

Shown is an overall summary with other studies showing cytokine-mediated transcription of NK1 (*[14]). Cytokine production in BCCs, via autocrine stimulation, can induce NK1 transcription (*[5,15]) to produce NK1-FL and NK1-Tr. Mir-519b interact with NK1-FL to suppress its translation, thereby allowing for increased NK1-Tr. Since miR-519b can suppress the RNA-binding protein, HuR (**[19]), perhaps there is another mechanism in the suppression of NK1-FL translation.

The in vitro studies were validated with nude BALB/c mice (Fig. 6). The knockdown of miR-519b prevented tumor formation (Fig. 6). Among 10 mice in which anti-miR519b were knockdown, tumor grew in three mice. We plotted these studies separately because it is unclear if this was due to the loss of the anti-miR in the tumor. At the time of injection, NK1-Tr was knockdown and only NK1-FL was expressed (Fig. 7A). Since the anti-miR prevented long-term growth of the tumor cells this brings into question the role of NK1-FL, which would be increased. It is likely that if the tumor is blocked from growing during the first week, the individual cells will undergo cell death. This premise is due to undetectable tumor at the end of the studies when the mice were euthanized. Overall, the studies are exciting and open avenues for future studies to determine if miR-519b could be utilized as a switch from dormancy to resurgence of BC. MiR-519b is undetectable in BCCs following gap junctional intercellular communication with stroma [31], supporting miR519b with a more aggressive form of BCCs.

The 3′UTR of NK1-Tr is different from that of NK1-FL (Fig. S1). While NK1-Tr showed no binding site for miR519b, similar sites were detected within the 3′ UTR of NK1-FL. Knockdown of miR519b showed no significant (p>0.05) change in the ratio of NK1-Tr (Fig. 5D). However, future studies are required to clone the 3′ UTR of NK1-Tr into the reporter vector to be sure that miR519b does not alter the translation of NK1-Tr. Also, since there are multiple sites for the miRNAs within the 3′UTR of NK1 (Fig. 4A) there was technical issues to mutate all of the sites. We are currently conducting studies in target-protection studies in other in vivo studies for a metastatic role of NK1-Tr.

An interesting observation are the different ratios of NK1-FL/NK1-Tr at transcription (nuclear run-on studies) and steady state (real-time PCR) (Figs 1B and 1D). At this time we do not have an explanation for this observation. However, is clear that there might be a rapid turnover of NK1-Tr since its level is decreased relative to NK1-FL after transcription. Another significant observation is the different ratio of NK1-Tr:NK1-FL between T47D and MDA-MB231 (Fig. 2B). Since MDA-MB-231 is a more aggressive cell line, we can only assume that there is higher transcription in these cells as compared to the lesser metastatic T47D.

The studies with transfected pre-miR519b showed no difference in NK1-Tr (Fig. 5A). This is expected since there was endogenous increase in miR519b, as indicated by real-time PCR (Fig. 3B). However, this study did not follow the transition of cancer cells from the time of epithlelial mesenchymal transition, or the stem cell fraction, to the highly aggressive cells that replicate rapidly. Other studies have shown the change in NK1-Tr with transformation in colitis associated cancer [7]. Thus, future studies are needed with different cancer cell subsets to determine if the change in miR519b in cancer cells would correlate with NK1-Tr and the aggressiveness of the cancer cell.

A summary of the findings (Fig. 7B) shows an increase in NK1 transcription by cytokines to produce high levels of NK1-Tr [5]. MiR-519b can suppress the translation of NK1-FL resulting in an advantage by NK1-Tr with regards to translation. Since miR519 can also reduce HuR, this could also destabilize NK1-FL to reduce its mRNA [19]. Of note are the relative differences in the ratios of NK1-FL to NK1-Tr protein in T47D and MDA-MB-231 (Figs 2B and 2C). Since MDA-MB-231 is a triple negative aggressive form of BC, it is possible that NK1-Tr might not be limited to an increase in cell growth but to increased metastasis. The studies also begin to address an evolving question on the role of miRNA in regulating specific spliced variants of genes [32]. Although this method of regulation was suggested based on bioinformatics studies, this study used molecular and functional studies to show a role for miRNA in suppressing a specific spliced variant, in this case, NK1-FL to facilitate oncogenesis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the Department of Defense, #W81XWH-10-1-0413

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E. Cancer Statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;61:133–134. doi: 10.3322/caac.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Munoz M, Rosso M, Covenas R. A new frontier in the treatment of cancer: NK-1 receptor antagonists. Curr Med Chem. 2010;17:504–516. doi: 10.2174/092986710790416308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brener S, Gonzalez-Moles MA, Tostes D, Esteban F, Gil-Montoya JA, Ruiz-Avila I, Bravo M, Munoz M. A role for the substance P/NK-1 receptor complex in cell proliferation in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2009;29:2323–2329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reddy BY, Greco SJ, Patel PS, Trzaska KA, Rameshwar P. RE-1-silencing transcription factor shows tumor-suppressor functions and negatively regulates the oncogenic TAC1 in breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2009;106:4408–4413. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809130106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patel HJ, Ramkissoon SH, Patel PS, Rameshwar P. Transformation of breast cells by truncated neurokinin-1 receptor is secondary to activation by preprotachykinin-A peptides. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2005;102:17436–17441. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506351102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rao G, Patel PS, Idler SP, Maloof P, Gascon P, Potian JA, Rameshwar P. Facilitating Role of Preprotachykinin-I Gene in the Integration of Breast Cancer Cells within the Stromal Compartment of the Bone Marrow. Cancer Res. 2004;64:2874–2881. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gillespie E, Leeman SE, Watts LA, Coukos JA, O'Brien MJ, Cerda SR, Farraye FA, Stucchi AF, Becker JM. Truncated neurokinin-1 receptor is increased in colonic epithelial cells from patients with colitis-associated cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2011;108:17420–17425. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114275108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fong TM, Anderson SA, Yu H, Huang RR, Strader CD. Differential activation of intracellular effector by two isoforms of human neurokinin-1 receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 1992;41:24–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Page NM. New challenges in the study of the mammalian tachykinins. Peptides. 2005;26:1356–1368. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2005.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klassert TE, Patel SA, Rameshwar P. Tachykinins and Neurokinin Receptors in Bone Marrow Functions: Neural-Hematopoietic Link. J Receptor Ligand Channel Res. 2010;2010:51–61. doi: 10.2147/jrlcr.s6509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pennefather JN, Lecci A, Candenas ML, Patak E, Pinto FM, Maggi CA. Tachykinins and tachykinin receptors: a growing family. Life Sci. 2004;74:1445–1463. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2003.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tuluc F, Lai JP, Kilpatrick LE, Evans DL, Douglas SD. Neurokinin 1 receptor isoforms and the control of innate immunity. Trends Immunol. 2009;30:271–276. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McConalogue K, Corvera CU, Gamp PD, Grady EF, Bunnett NW. Desensitization of the Neurokinin-1 Receptor (NK1-R) in Neurons: Effects of Substance P on the Distribution of NK1-R, Galpha q/11, G-Protein Receptor Kinase-2/3, and beta-Arrestin-1/2. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:2305–2324. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.8.2305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bandari PS, Qian J, Yehia G, Seegopaul HP, Harrison JS, Gascon P, Fernandes H, Rameshwar P. Differences in the expression of neurokinin receptor in neural and bone marrow mesenchymal cells: implications for neuronal expansion from bone marrow cells. Neuropeptides. 2002;36:13–21. doi: 10.1054/npep.2002.0869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramkissoon SH, Patel PS, Taborga M, Rameshwar P. Nuclear Factor-kB Is Central to the Expression of Truncated Neurokinin-1 Receptor in Breast Cancer: Implication for Breast Cancer Cell Quiescence within Bone Marrow Stroma. Cancer Res. 2007;67:1653–1659. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okamoto T, Mitsuhashi M, Kikkawa Y. Fluorometric Nuclear Run-On Assay with Oligonucleotide Probe Immobilized on Plastic Plates. Analy Biochem. 1994;221:202–204. doi: 10.1006/abio.1994.1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chaudhuri AA, So AY-L, Mehta A, Minisandram A, Sinha N, Jonsson VD, Rao DS, O'Connell RM, Baltimore D. Oncomir miR-125b regulates hematopoiesis by targeting the gene Lin28A. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2012;109:4233–4238. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200677109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Munoz M, Covenas R. Neurokinin-1 receptor: a new promising target in the treatment of cancer. Discov Med. 2010;10:305–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abdelmohsen K, Srikantan S, Kuwano Y, Gorospe M. miR-519 reduces cell proliferation by lowering RNA-binding protein HuR levels. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2008;105:20297–20302. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809376106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oh HS, Moharita A, Potian JG, Whitehead IP, Livingston JC, Castro TA, Patel PS, Rameshwar P. Bone Marrow Stroma Influences Transforming Growth Factor-beta Production in Breast Cancer Cells to Regulate c-myc Activation of the Preprotachykinin-I Gene in Breast Cancer Cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6327–6336. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rameshwar P, Gascon P. Induction of negative hematopoietic regulators by neurokinin-A in bone marrow stroma. Blood. 1996;88:98–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greco SJ, Rameshwar P. MicroRNAs regulate synthesis of the neurotransmitter substance P in human mesenchymal stem cell-derived neuronal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2007;104:15484–15489. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703037104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qian J, Yehia G, Molina CA, Fernandes A, Donnelly RJ, Anjaria DJ, Gascon P, Rameshwar P. Cloning of Human Preprotachykinin-I Promoter and the Role of Cyclic Adenosine 5'-Monophosphate Response Elements in Its Expression by IL-1 and Stem Cell Factor. J Immunol. 2001;166:2553–2561. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.4.2553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greco SJ, Patel SA, Bryan M, Pliner LF, Banerjee D, Rameshwar P. AMD3100-mediated production of interleukin-1 from mesenchymal stem cells is key to chemosensitivity of breast cancer cells. Am J Cancer Res. 2011;1:701–715. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Real S, Marzese D, Gomez L, Mayorga L, Roque M. Development of a Premature Stop Codon-detection method based on a bacterial two-hybrid system. BMC Biotechnology. 2006;6:38. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-6-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang WQ, Wang JG, Chen L, Wei HJ, Chen H. SR140333 counteracts NK-1 mediated cell proliferation in human breast cancer cell line T47D. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2010;29:55. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-29-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosso M, Robles-Frias MJ, Covenas R, Salinas-Martin MV, Munoz M. The NK-1 receptor is expressed in human primary gastric and colon adenocarcinomas and is involved in the antitumor action of L-733,060 and the mitogenic action of substance P on human gastrointestinal cancer cell lines. Tumour Biol. 2008;29:245–254. doi: 10.1159/000152942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frucht H, Gazdar AF, Park JA, Oie H, Jensen RT. Characterization of Functional Receptors for Gastrointestinal Hormones on Human Colon Cancer Cells. Cancer Res. 1992;52:1114–1122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gonzalez Moles MA, Mosqueda-Taylor A, Esteban F, Gil-Montoya JA, Diaz-Franco MA, Delgado M, Munoz M. Cell proliferation associated with actions of the substance P/NK-1 receptor complex in keratocystic odontogenic tumours. Oral Oncol. 2008;44:1127–1133. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2008.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Munoz M, Rosso M, Robles-Frias MJ, Salinas-Martin MV, Rosso R, Gonzalez-Ortega A, Covenas R. The NK-1 receptor is expressed in human melanoma and is involved in the antitumor action of the NK-1 receptor antagonist aprepitant on melanoma cell lines. Lab Invest. 2010;90:1259–1269. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2010.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lim PK, Bliss SA, Patel SA, Taborga M, Dave MA, Gregory LA, Greco SJ, Bryan M, Patel PS, Rameshwar P. Gap Junction-Mediated Import of MicroRNA from Bone Marrow Stromal Cells Can Elicit Cell Cycle Quiescence in Breast Cancer Cells. Cancer Res. 2011;71:1550–1560. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martignetti L, Zinovyev A, Barillot E. Identification of shortened 3' untranslated regions from expression arrays. J Bioinform Comput Biol. 2012;10:1241001. doi: 10.1142/S0219720012410016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.