Abstract

The intrinsic antileukemic effect of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) is dependent on genetic disparity between donor and recipient, intimately associated with graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), and mediated by lymphocytes contained in or derived from the donor hematopoietic cell graft. Three decades of intense effort have not identified clinical strategies that can reliably separate the graft-versus-leukemia (GVL) effect from the alloimmune reaction that drives clinical GVHD. For patients who require HCT and for whom two or more HLA-A, -B, -C, and -DRB1-matched donor candidates can be identified, consideration of donor and recipient genotype at additional genetic loci both within and outside the MHC may offer the possibility of selecting the donor (candidate[s]) that poses the lowest probability of GVHD and the highest probability of a potent GVL effect. Strategies for engineering conventional donor lymphocyte infusion also hold promise for prevention or improved treatment of posttransplant relapse. The brightest prospects for selectively enhancing the antileukemic efficacy of allogeneic HCT, however, are likely to be interventions that are designed to enhance specific antitumor immunity via vaccination or adoptive cell transfer, rather than those that attempt to exploit donor alloreactivity against the host. Adoptive transfer of donor-derived T cells genetically modified for tumor-specific reactivity, in particular, has the potential to transform the practice of allogeneic HCT by selectively enhancing antitumor immunity without causing GVHD.

Keywords: graft-versus-leukemia, graft-versus-host disease, conditioning regimen, adoptive immunotherapy

Introduction

At least three independent lines of evidence support the existence of a GVL effect that operates in allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. First, complete remission of malignant disease after withdrawal of immune suppression has occasionally been reported in allogeneic HCT patients whose cancers persisted or recurred posttransplant. Second, complete remission has frequently been observed in HCT patients who received posttransplant infusions of donor-derived lymphocytes for persistent or recurrent malignancy. Third, partial or complete regression of malignancy in patients who undergo allogeneic HCT with nonmyeloablative (low intensity) conditioning regimens that permit stable engraftment of donor hematopoietic cells but have little or no direct tumoricidal activity provides what is arguably the clearest and most compelling demonstration of the GVL effect. Cellular and molecular dissection of the GVL effect has been a major focus of many laboratories over the last two decades, and these collective efforts are facilitating the development of strategies for selectively enhancing the GVL effect without inducing or aggravating GVHD.

Defining characteristics of the GVL effect in human allogeneic HCT

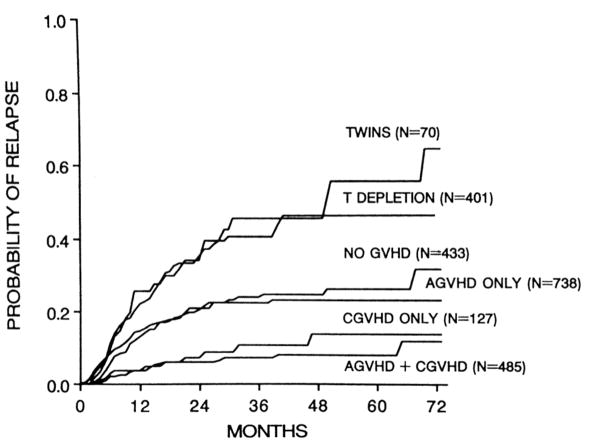

The essential characteristics of the GVL effect were first identified in retrospective analyses of relapse rates following HCT with bone marrow grafts from major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-identical sibling donors for early-stage or for advanced leukemia (1–3). Comparison of the relapse rates seen in patients who developed no GVHD, acute GVHD, chronic GVHD, or both acute and chronic GVHD, revealed that the GVL affect is strongly associated with the development of GVHD (Figure 1); a subsequent large study of transplants for chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) further suggested that the strength of the GVL effect was correlated with the incidence and severity of GVHD (4). Comparison of the relapse rate observed in MHC-matched allogeneic HCT recipients who did not develop acute or chronic GVHD with that observed in recipients of HCT from syngeneic donors demonstrated that there is an anti-leukemic effect of allogeneic HCT per se that is independent of clinically apparent GVHD. Finally, comparison of the relapse rate seen in MHC-matched allogeneic HCT recipients who received unmodified, T-replete bone marrow grafts with that observed in recipients of allogeneic grafts from which T cells had been depleted prior to infusion revealed that the antileukemic effect associated with allogeneic HCT is impaired by removal of T cells from the bone marrow graft.

Figure 1.

Actuarial probability of relapse among 2,254 recipients of allogeneic BMT from HLA-identical sibling donors transplanted for CML in first chronic phase, ALL in first remission, or AML in first remission, according to the type of graft and the development of acute or chronic GVHD. Reproduced with permission from Horowitz et al. (3).

Genetic determinants, effector cells, and target molecules of the GVL effect

The GVL effect requires genetic disparity between donor and recipient, and is mediated primarily by lymphocytes contained in or derived from the donor hematopoietic cell graft. Although a comprehensive mechanistic understanding of the GVL effect remains elusive, research in many labs over the past two decades has identified many of the critical genetic determinants, effector cells, and target molecules of the GVL effect. It is clear that the GVL effect is not a single, homogeneous phenomenon, and that the mechanisms that mediate GVL in any given transplant recipient are in large part determined by the degree and nature of genetic disparity between donor and recipient, the source, composition, and processing of the hematopoietic cell graft from the donor, and the recipient tumor type. As the range of malignant diseases for which allogeneic HCT is performed has steadily expanded from acute myelogenous leukemia (AML), acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), and CML – which essentially comprised the sole malignant indications for the procedure in the 1980s and 1990s – to a broader range of hematologic neoplasms that also includes myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), myeloproliferative disorders, chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma, multiple myeloma, and other disorders, it has become increasingly apparent that the extent to which GVL activity is associated with the incidence and severity of GVHD is not the same for all tumors. Indeed, a recent retrospective study of 48,111 first allogeneic transplants reported to the EBMT group between 1998 and 2007 (5) demonstrated that GVL activity – as inferred from posttransplant relapse rates – is most strongly associated with GVHD in patients with CML and ALL, less so in those with MDS and lymphoma, and is only weakly associated with GVHD in patients with AML and plasma cell disorders. These observations imply that the mechanisms that mediate GVL after allogeneic HCT do not completely overlap with those that mediate GVHD.

T lymphocytes and natural killer (NK) cells of donor origin are clearly the primary GVL effector cells in most allogeneic transplants. Donor CD4+ and CD8+ T cells recognizing peptide-MHC complexes on the surface of recipient cells are the central mediators of the GVL effect in HCT recipients who receive T-replete grafts from MHC-matched donors. Accumulating evidence, however, suggests that donor NK cells also play an important role in GVL in the T-replete, MHC-matched transplant setting. In contrast, donor NK cells carrying receptors for peptide-MHC molecules as well as other ligands on recipient target cells are the primary mediators of GVHD in recipients of grafts from human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-haploidentical and multiple HLA antigen-mismatched donors, settings in which extensive in vivo or in vitro T-cell depletion of the graft is required to prevent lethal GVHD.

GVL in multiple HLA antigen-mismatched and HLA-haploidentical HCT

Pioneering studies by the transplant group in Perugia suggested that eradication of leukemic cells in recipients of extensively T-depleted grafts from haploidentical or multiple HLA-mismatched donors was in large part due to alloreactive donor-derived NK cells (6). Functional analysis of donor NK cells from HLA-haploidentical HCT recipients revealed potent cytotoxicity against recipient lymphocytes, dendritic cells, and myeloid (but not lymphoid) leukemic blasts, with little if any recognition of recipient nonhematopoietic cells. Analysis of donor and recipient genotypes at the MHC and at the killer-cell immunoglobulin-like receptor (KIR) locus on chromosome 19q suggested that both the posttransplant eradication of leukemia and the in vitro NK cytotoxicity could be explained by a “missing self” model of NK alloreactivity in which the key variables were the MHC class I alleles expressed by the recipient but not the donor. The Perugia group’s initial clinical experience suggested that NK alloreactivity – and clinical GVL activity – predicted by the missing self model was not closely correlated with the development of clinically significant GVHD (6), but this conclusion was not supported by their subsequent experience (7). The critical contribution of donor NK alloreactivity to GVL activity in haploidentical HCT has been extensively confirmed by multiple subsequent studies, and has prompted the development of other models for more accurate prediction of donor NK alloreactivity. The most prominent alternative model, commonly referred to as the “missing ligand” model, uses as its primary variables both the MHC class I genotypes of the donor and recipient and the KIR haplotype and gene content of the donor. It is not yet clear which of the several proposed models for predicting donor NK alloreactivity in haploidentical HCT has the greatest accuracy.

Analysis of leukemic blasts obtained from patients with recurrent AML or MDS after haploidentical HCT has provided compelling additional support for the notion that donor lymphocytes with specificity for products of recipient MHC genes on the unshared haplotype are the primary mediators of GVL activity in the haploidentical setting. A seminal study of 17 patients who relapsed after haploidentical HCT followed by posttransplant infusion of donor T cells revealed that leukemic blasts obtained from 5 of the 17 patients at relapse had lost the entire recipient MHC haplotype not shared by the donor (8). The mechanism of MHC haplotype loss was felt to be mitotic recombination that created uniparental disomy for chromosome 6p. Similar observations were reported in a subsequent study that showed loss of the unshared recipient MHC haplotype on chromosome 6p, once again presumably via mitotic recombination creating uniparental disomy, in leukemic blasts obtained from 2 of 3 children with AML who had relapsed after HCT from HLA-haploidentical related donors (9).

GVL in T-replete MHC-identical or -closely matched HCT

The increased relapse rate observed in recipients of T-depleted hematopoietic cell grafts from MHC-identical related (3) or closely MHC-matched unrelated (10) donors demonstrated that T cells contained in or derived from the donor hematopoietic cell graft play a critical role in GVL activity after MHC-matched HCT. There is abundant evidence that both CD8+ (11–13) and CD4+ (14, 15) donor T cells can contribute to GVL in this setting. Accumulating evidence, however, most of it indirect and inferred from genotyping donor and recipient MHC and KIR loci, also suggests that alloreactive donor NK cells may contribute to GVL that occurs after HCT from MHC-matched related or unrelated donors, primarily in patients with myeloid leukemia. The current consensus holds that the contribution from donor T cells is both more potent and more important than the contribution from donor NK cells, but it is likely that the relative contributions of donor T and NK cells in any given patient are strongly influenced by the immunogenetic relationship of the donor and recipient, the source, processing, and other characteristics of the hematopoietic cell graft, the recipient’s conditioning regimen and GVHD prophylaxis, and the nature of the recipient’s malignancy.

Minor histocompatibility antigens as targets for GVL responses

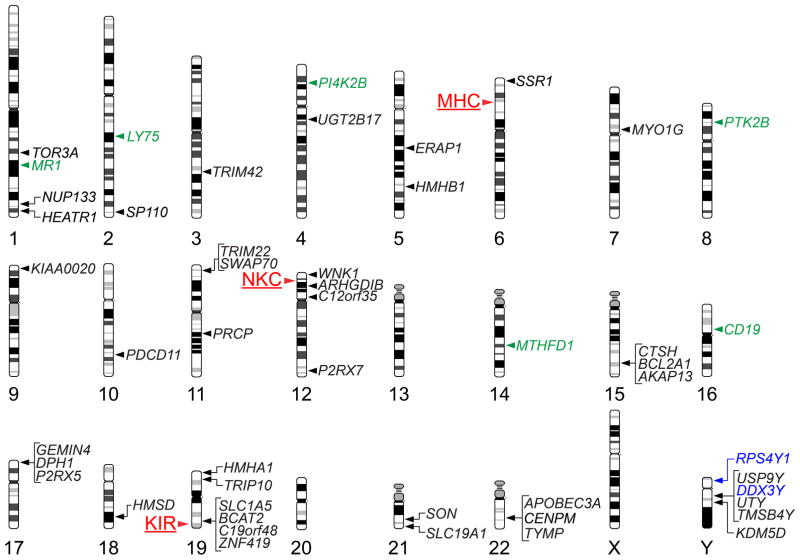

The initial, and likely primary, targets of the donor CD8+ and CD4+ T cell response in MHC-matched HCT are minor histocompatibility (H) antigens encoded by polymorphic genetic loci located outside the MHC that are presented by recipient MHC class I and II molecules respectively. Minor H antigens are created by the extensive sequence and structural variation that characterizes the human genome; as of late 2012, at least 49 different genes have been shown to encode minor H antigens recognized by either CD8+ or CD4+ T cells in recipients of MHC-matched HCT (Figure 2). The majority of these genes are autosomal, with almost every chromosome represented, but at least 6 different genes on the Y chromosome have been shown to encode male-specific minor H antigens that can elicit donor T cell responses in male recipients of female hematopoietic cell grafts. Abundant evidence demonstrates that T cell responses against both autosomal (12, 13) and Y chromosome-encoded (16) minor H antigens can contribute to GVL activity. It is widely assumed that T cell responses against minor H antigens such as HA-1 (17) that are selectively or exclusively expressed in hematopoietic cells, including malignant blood cells, will selectively contribute to GVL, and that responses against minor H antigens such as HA-8 (18) that are expressed on both hematopoietic and nonhematopoietic cells are likely to contribute to both GVL activity as well as GVHD. Although definitive experimental tests of this assumption may ultimately prove its veracity, the fact that broadly expressed minor H antigens far outnumber those with hematopoietic-specific expression suggests that clinical exploitation of this selectivity may be a challenge.

Figure 2.

(A) Map of genetic loci that can influence histocompatibility in the allogeneic HCT setting. The chromosomal location of the MHC, and of two other multigene clusters, the NKC and the KIR locus, are indicated by red labels and arrowheads to the left of the corresponding chromosomes. The chromosomal locations of genes that have been shown to encode T lymphocyte-defined minor histocompatibility antigens are indicated by labels and arrowheads to the right of the corresponding chromosomes; genes that encode class I MHC-restricted minor H antigens recognized by CD8+ T cells are indicated by black labels, those that encode class II MHC-restricted minor H antigens recognized by CD4+ T cells are indicated by green labels, and those that encode both class I- and class II MHC-restricted minor H antigens are indicated by blue labels.

Although a large number of distinct minor H antigens have already been characterized, it is likely that many more exist, due to the considerable sequence and structural variation that characterizes the human genome (19, 20). Indeed, most of the minor H antigens identified to date are created by nonsynonymous single nucleotide polymorphisms (nsSNPs) in the coding sequence of protein-encoding genes (20), and data from the pilot phase of the 1000 Genomes Project (19) demonstrate that any two unrelated individuals will likely differ from one another at 10,000 – 11,000 nsSNPs. There is also a large number of structurally variant coding regions in the human genome that could create minor H antigens like those encoded by the UGT2B17 gene (21) if they were homozygously absent from the donor genome but present in the recipient genome. The total number of human minor H antigens that could elicit T cell responses in an allogeneic HCT setting is therefore very large, and consequently it is likely that all allogeneic HCT donor/recipient pairs, regardless of their biologic relationship, will be mismatched for many minor H antigens.

Nonpolymorphic GVL targets

In addition to T cell responses against recipient minor H antigens, donor T cell responses against nonpolymorphic antigens encoded by genes that are over- or aberrantly expressed in myeloid and lymphoid leukemic cells can be detected in recipients of MHC-matched transplants and probably contribute to GVL activity. HLA-A*0201-restricted CD8+ T cells specific for a peptide, termed PR1, encoded by the proteinase-3 and neutrophil elastase genes were detected at increased frequency in the blood of many HLA-A*0201+ CML patients who achieved remission after MHC-matched HCT (22). Proteinase-3, also known as myeloblastin, and elastase are both major constituents of the primary azurophil granules of normal promyelocytes as well as AML and CML blasts. CD8+ T cell responses to peptides derived from the WT1 oncoprotein (23), and CD8+ and CD4+ responses to cancer-testis antigens such as NY-ESO-1 (24) and several members of the MAGE family (25), have also been detected after MHC-matched HCT for acute leukemia and multiple myeloma. Donor T-cell responses against tumor-specific antigens also develop in patients with solid tumors who undergo allogeneic HCT. A potent tumor-specific CD8+ T cell response directed against an antigenic peptide encoded by human endogenous retrovirus type E was detected in a patient with metastatic renal cell carcinoma who achieved a durable complete remission of the disease after nonmyeloablative MHC-matched HCT (26).

Contributions to GVL from NK and B cells

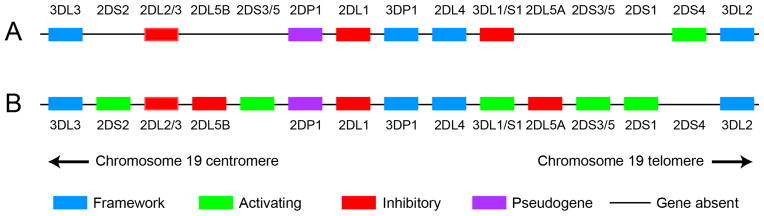

Although there is little direct evidence for a role of donor NK cells in GVL after MHC-matched HCT, several retrospective analyses have demonstrated provocative associations between the relapse rate of myeloid leukemias, donor and recipient MHC genotype, and donor KIR haplotype and gene content, in both related (27–29) and unrelated (30–34) HCT pairs. KIR genes encode transmembrane receptors that are expressed selectively or exclusively in NK cells and subsets of αβ or γδ T cells, bind to specific subsets of MHC class I alleles in a manner that is influenced by MHC-bound peptide (35–38), and participate in specific recognition of target cells by NK and T cells. The KIR genes are both polymorphic and highly homologous with one another, and their products are classified according to the length of their cytoplasmic tails – short or long – which are thought to have activating or inhibitory effects, respectively, on NK cytotoxicity and effector function. The gene content of the KIR locus on chromosome 19q is also polymorphic, and two basic types of KIR haplotypes – termed A and B – distinguished primarily by their content of genes for activating receptors have been identified (Figure 3). The largest and most compelling studies of MHC and KIR genotype and posttransplant relapse have shown significant associations between the presence in the donor of a type B KIR haplotype, or one or more components thereof – in particular the KIR2DS1 gene that encodes an activating NK receptor – and decreased rate of relapse in recipients undergoing unrelated HCT for AML and other myeloid neoplasms (32–34). High levels of donor NK chimerism in the early posttransplant period have also been significantly associated with a lower rate of relapse in recipients of nonmyeloablative HCT (39). Collectively, the results of these studies suggest that alloreactive donor NK cells can make an important contribution to GVL activity in patients with myeloid leukemias who receive grafts from closely HLA-matched related or unrelated donors.

Figure 3.

Basic organization and gene content of the human KIR locus on chromosome 19q. Two hypothetical haplotypes are illustrated: an A (top) and a B (bottom) haplotype. Framework genes (which can be coding genes or pseudogenes) are illustrated in blue; non-framework activating genes are in green, inhibitory genes in red, and pseudogenes in purple. Adapted from http://www.ebi.ac.uk/ipd/kir/sequenced_haplotypes.html.

Donor B lymphocytes may also contribute to GVL activity in selected HCT patients. Antibody responses to proteins expressed in recipient tumor cells have been detected in CML (40) and multiple myeloma (41) patients who relapsed after MHC-matched HCT and subsequently achieved complete remission after donor lymphocyte infusion (DLI). Although most of the proteins recognized by antibodies detected after DLI were intracellular and not expressed on the cell surface, antibodies to B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA), a transmembrane protein with an extracellular domain, were found only in post-DLI responder sera from patients with multiple myeloma (41). Serum containing anti-BCMA antibodies was able to induce complement-mediated lysis and antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity of a tumor cell line transfected with a BCMA cDNA, as well as primary myeloma cells expressing BCMA. These observations suggested that BCMA may be a target of the graft-versus-myeloma response initiated by DLI. Antibodies to tumor-specific antigens such as NY-ESO-1 that are associated with donor NY-ESO-1-specific CD8+ and CD4+ T cell responses have also been detected in myeloma patients after HCT (24); whether these antibodies contributed to posttransplant graft-versus-myeloma activity, or simply served as a marker for it, is unknown.

Strategies for enhancing GVL and preventing GHVD

The development of clinical strategies to enable selective manipulation of the antileukemic effect of allogeneic HCT without exacerbation of GVHD remains one of the highest priorities in HCT research. Much current effort is focused on enhancing the intrinsic GVL reaction, or preventing GVHD without impairing the GVL effect, through identification and utilization of optimal donors. Motivated by the recognition that the incidence and severity of GVHD are correlated with intensity of the pretransplant conditioning regimen, the design of optimal non-toxic conditioning regimens is another active area of investigation, as is the design of strategies for delivering more effective and less toxic posttransplant DLI to prevent or treat relapse. Without question, one of the most exciting areas in current transplant research is the development of tumor-specific immune therapy, based on vaccination or adoptive cell transfer, which does not rely on alloimmunity for its therapeutic efficacy.

Improved donor selection for enhanced GVL and less GVHD

Selection of unrelated hematopoietic cell donors for patients requiring allogeneic HCT is focused on identification of individuals who are identical with the intended recipient at a limited number of specific loci within the MHC, which spans > 3.3 megabases on the short arm of chromosome 6 and includes several hundred protein-coding genes. The National Marrow Donor Program currently recommends targeted sequencing of exons 2 and 3 of the HLA-A, -B, and -C genes as well as exon 2 of HLA-DRB1 (42) in patients and candidate donors. Studies from several large retrospective analyses have suggested, however, that donor/recipient matching at additional loci within the MHC – particularly at loci that encode the α and β chains of HLA-DP heterodimers (43–45) – could potentially lead to improved transplant outcome, in large part through lower rates of severe GVHD. In patients who are candidates for unrelated HCT and at high risk of posttransplant relapse, however, deliberate selection of a donor who is mismatched with the recipient at HLA-DP could prove to be beneficial, as such mismatches are also associated with a reduced risk of posttransplant relapse (44, 46, 47). The results of a recent randomized trial (48) have also suggested that the type of hematopoietic cell graft selected for patients with HLA-A, -B, -C, and -DRB1-matched unrelated donors will influence the risk of GVHD, the significance and clinical utility of which might differ for patients with early- and late-stage leukemia.

Consideration of donor and recipient genotype at loci outside the MHC might potentially enable selective exploitation of the GVL effect, particularly for patients with myeloid leukemias. The lower rates of relapse observed in patients with myeloid leukemias who receive grafts from donors carrying one or more type B KIR haplotypes (32, 33) – or KIR genes such as KIR2DS1 that characterize such haplotypes (34) – suggest that prospective donor KIR typing for patients with two or more HLA-A, -B, -C, and -DRB1-matched donor candidates might prove beneficial for the selection of the optimum donor. Better understanding the components of the donor type B haplotypes that are responsible for the lower relapse rate and superior outcome in myeloid leukemia patients is a high-priority research objective.

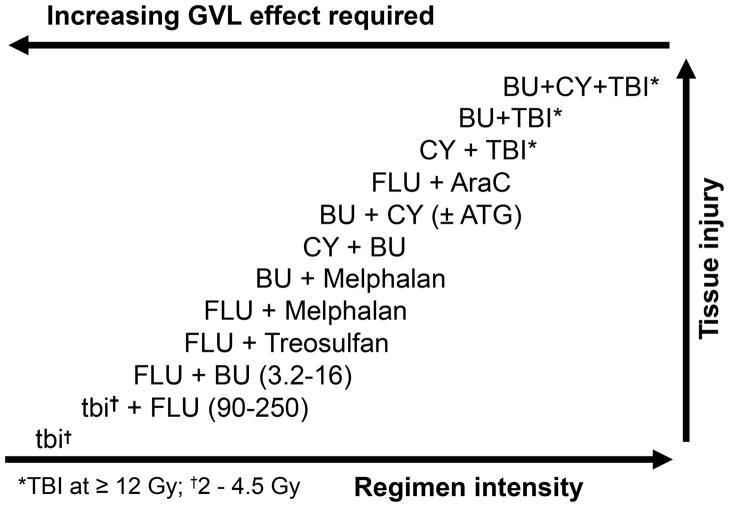

Lowering risk of GVHD through optimization of transplant conditioning

Any conditioning regimen administered to patients in preparation for HCT will alter the milieu into which donor cells are infused and thereby will affect the interaction of donor cells with the host. Various studies, including randomized trials, have shown that the incidence and severity of GVHD, certainly in its acute form, will increase with the intensity of the conditioning regimen, particularly those utilizing high dose total body irradiation (49, 50). This effect is related to tissue injury and the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which, together with signals derived from donor cells, will lead to what has been described as a “cytokine storm”. Inflammation, in addition to classical immunological interactions, contributes to the clinical manifestations of GVHD. A broad spectrum of conditioning regimens is currently utilized for allogeneic HCT (Figure 4), dependent upon the disease for which the HCT is carried out, the source of stem cells to be used, and the patient’s overall condition, among others. There is evidence that low intensity (non-myeloablative) regimens are associated with less severe, and possibly a lower incidence of, acute GVHD (51); however, GVHD may occur later than observed with high dose regimens, and the incidence of chronic GVHD does not appear to differ (51).

Figure 4.

Reciprocal relationship between the intensity of conditioning regimens that have been used for allogeneic HCT and the required antileukemic contribution from the GVL effect to achieve a comparable rate of posttransplant relapse. The relative degree of tissue injury typically observed with each regimen is also indicated. TBI and tbi: total body irradiation; BU: busulfan; CY: cyclophosphamide; FLU: fludarabine; AraC: cytarabine; ATG: anti-thymocyte globulin.

Intriguing is the recent observation that treatment of patients (pretransplant), donors (before stem cell donation), or both with statin-containing drugs (administered for dyslipidemia) was associated with a reduced incidence of GVHD (52, 53). In particular, donor pre-treatment significantly reduced the frequency of severe acute GVHD. Of note was the fact that a benefit was seen only in patients who received cyclosporine for GVHD prophylaxis, but not those given tacrolimus. Ongoing studies are aimed at confirming those retrospective data in prospective trials. Reduced frequencies of chronic GVHD were reported when anti-thymocyte globulin (thymoglobulin) was incorporated into the conditioning regimen (54), although recent data in patients prepared with non-myeloablative regimens are controversial (55).

It is unlikely that modifications of conditioning regimens by themselves will prevent GVHD. However, reducing conditioning-related toxicity is likely to reduce or eliminate factors that may set the stage for or aggravate GVHD.

Engineering DLI for improved antileukemic activity and less toxicity

DLI continues to be a common strategy for preventing or treating posttransplant relapse despite its limited antileukemic efficacy and frequent toxicity. A pilot study investigated the addition to DLI of immune checkpoint inhibition with a single dose of ipilimumab (a blocking antibody directed at CTLA4) to enhance its antileukemic potency (56). No aggravation of GVHD by ipilimumab was seen in 29 treated patients, although organ-specific immune adverse events were noted in 4 patients, and 3 objective clinical responses (2 CR, 1 PR) were observed. Treatment with ipilimumab was not associated with any significant change in the absolute number of CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ cells in the peripheral blood (57). Interruption of signaling through the PD-1/PD-L1 axis with blocking monoclonal antibodies was associated with durable regression of several different types of advanced solid tumors in recent trials (58, 59), and it is conceivable that interruption of PD-1/PD-L1 signaling with these agents might likewise enhance the antitumor efficacy of DLI. Depletion of CD4+CD25+ cells from DLI products, without or with lymphodepleting chemotherapy in the patient prior to infusion, was also investigated in a recent pilot trial (60), in which durable GVL activity accompanied by GVHD was observed in several patients who had not responded to unmodified DLI.

Tumor-specific immunotherapy with vaccination or adoptive cell transfer

Three decades of efforts to dissect the antileukemic component of the “intrinsic” graft-versus-host reaction have not yet led to the identification of interventions that can reliably separate it from clinical GVHD. Much current effort, consequently, is directed toward the development and application of therapeutic approaches that do not rely on manipulation of alloimmunity, but rather rely on enhancing immunity to tumor-associated or tumor-specific antigens. Indeed, many antigens that are currently being studied as targets for immunotherapy after allogeneic HCT have already undergone extensive evaluation as targets for vaccination or adoptive cell transfer in the autologous setting.

A variety of vaccine-based approaches to stimulate active tumor immunity after allogeneic HCT are currently under investigation. Most of these efforts involve immunization of the HCT recipient, as the safety of immunizing healthy donors against tumor-specific antigens has, in general, not yet been established. Notable exceptions, however, include several trials in which MHC-matched sibling donors of patients with multiple myeloma were vaccinated with purified idiotype protein from their respective siblings (61–63). No significant toxicity of vaccination with purified idiotype protein was reported in these studies, which also demonstrated cellular and humoral idiotype-specific immune responses in the donors as well as in the sibling recipients to whom they donated bone marrow, and, in one case, lymphocytes. Current vaccination studies, however, are primarily focused on eliciting immune responses to tumor-associated antigens that are shared by many patients, as opposed to being patient-specific. Vaccination with synthetic PR1 peptide (derived from proteinase 3 or neutrophil elastase) and peptides contained within the sequence of the WT1 or BCR-ABL proteins has been extensively evaluated in the nontransplant setting. Although vaccination with these peptides can elicit CD8+ and CD4+ T cell responses, the responses, particularly with PR1 vaccination, demonstrate relatively low avidity and are generally not durable. Not surprisingly, the clinical responses observed in these trials have not yet been sufficiently encouraging to warrant extensive evaluation of this approach in the more complicated setting of allogeneic HCT. Recent studies with a murine monoclonal antibody recognizing the PR1/HLA-A*0201 complex demonstrated that the complex is unequivocally present on the surface of normal hematopoietic stem cells, myeloblasts, and monocytes (64), which may explain the failure of PR1 peptide vaccination to generate high-avidity HLA-A*0201-restricted PR1-specific CD8+ T cell responses in HLA-A*0201+ individuals.

Patient-specific cellular vaccines have been administered to allogeneic HCT recipients and have been shown to be safe and immunogenic. Examples include a vaccine comprising irradiated autologous leukemic blasts admixed with skin fibroblasts transduced with the IL2 and CD40LG (CD40 ligand) genes (65), and one consisting of irradiated autologous leukemic blasts transduced with the CSF2 (GMCSF) gene (66). Although these vaccines were tested in single-arm, early-stage trials that were not designed to provide definitive assessment of vaccine contribution to GVL activity, the outcome of patients treated on both trials when compared with historical controls was encouraging. Further evaluation of these promising approaches to enhancing tumor-specific immunity after allogeneic HCT, thus, appears to be warranted.

Advances in two key areas of research – adoptive cellular therapy for the treatment of viral diseases after allogeneic HCT, and methodology for genetically modifying T cells to redirect their specificity – are collectively stimulating the development of a new generation of adoptive transfer strategies for enhancing both antiviral and antileukemic immunity after allogeneic HCT. Adoptive therapy with donor T cells after allogeneic HCT was pioneered two decades ago by investigators who administered donor-derived CMV- (67) and EBV- (68) specific T cells to prevent posttransplant CMV reactivation or to control EBV-related lymphoproliferative disease (EBV-LPD). Although the T cells administered in these studies were of donor origin, infusion of these virus-specific T cell products did not trigger or exacerbate GVHD in the recipients. Subsequent clinical experience with adoptive transfer of donor-derived polyclonal EBV-specific T cell lines demonstrated the remarkable safety and long-term efficacy of this procedure in the prophylaxis and treatment of posttransplant EBV-LPD, and confirmed that it did not cause or aggravate GVHD. More recently, methodology for the manufacture of cellular therapy products with specificity for multiple viruses – CMV, EBV, and adenovirus – from both adult peripheral blood (69) as well as cord blood (70) have been developed, and the safety and antiviral efficacy of these products has been confirmed by multiple groups.

Refinement of techniques for redirecting the antigenic specificity of T cells by genetic modification with T cell receptors (TCRs) or chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) is the second key development that is enabling a new generation of cellular therapy products for selectively enhancing GVL activity after allogeneic HCT. Genetic modification of virus-specific donor T cells with transgenic TCRs (71) or CARs (72, 73) specific for molecules that are selectively or exclusively expressed on the surface of leukemic cells should, in principle, create a population of effector cells with potent and specific antitumor activity, by virtue of their transgenic TCRs or CARs, which will not cause GVHD after adoptive transfer, because their native T cell receptors are specific for viral antigens rather than self antigens. Several CARs specific for CD19 have already been extensively tested in the autologous setting in patients with CD19+ B-lymphoid malignancies, with overall quite promising and some spectacular results (74–78). Donor-derived CD19-specific CAR-transduced T cells have also been administered to one patient with progressive CLL after allogeneic HCT who subsequently experienced dramatic disease regression (79). A promising alternative approach to minimizing the risk of GVHD associated with adoptive transfer of polyclonal TCR- or CAR-transduced donor T cells is based on the use of zinc finger nucleases to disrupt the endogenous TCR α and β chain loci in the T cells (80), which completely abrogates surface expression of their natively encoded TCRs without impairing the specificity or function of the transgenic receptor.

Conclusions

In the three decades that have elapsed since the GVL effect associated with allogeneic HCT was first identified in retrospective clinical studies, cellular and molecular studies have identified many of the genetic loci, effector cells, and target molecules that mediate this remarkably potent immune response – which, however, still remains frustratingly accompanied by the toxicities of GVHD. GVL activity in most patients is attributable to a diverse population of both T and NK cells, and quite possibly B cells as well, with broad antigenic specificity that is nonetheless primarily focused on recipient alloantigens. The considerable sequence and structural variation that characterizes the human genome – which is apparent even when the genomes of first-degree relatives are compared – implies that selectively exploiting the genetic disparity between donor and recipient that ultimately drives both GVL and GVHD to enhance the former without aggravating the latter will continue to be a challenge. Interventions that enhance specific antitumor immunity rather than alloimmunity after allogeneic HCT will likely have the greatest impact in the future on the outcome of allogeneic HCT.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health HL105914 and AI033484.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interests

The authors have declared no conflicting interests.

References

- 1.Weiden PL, Flournoy N, Thomas ED, et al. Antileukemic effect of graft-versus-host disease in human recipients of allogeneic-marrow grafts. N Engl J Med. 1979;300:1068–73. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197905103001902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weiden PL, Sullivan KM, Flournoy N, Storb R, Thomas ED. Antileukemic effect of chronic graft-versus-host disease: contribution to improved survival after allogeneic marrow transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1981;304:1529–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198106183042507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horowitz MM, Gale RP, Sondel PM, et al. Graft-versus-leukemia reactions after bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 1990;75:555–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gratwohl A, Brand R, Apperley J, et al. Graft-versus-host disease and outcome in HLA-identical sibling transplantations for chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2002;100:3877–86. doi: 10.1182/blood.V100.12.3877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stern M, de Wreede LC, Brand R, et al. Impact of graft-versus-host disease on relapse after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, an EBMT megafile study. ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts. 2012;120:469. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ruggeri L, Capanni M, Urbani E, et al. Effectiveness of donor natural killer cell alloreactivity in mismatched hematopoietic transplants. Science. 2002;295:2097–100. doi: 10.1126/science.1068440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ruggeri L, Mancusi A, Capanni M, et al. Donor natural killer cell allorecognition of missing self in haploidentical hematopoietic transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia: challenging its predictive value. Blood. 2007 doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-038687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vago L, Perna SK, Zanussi M, et al. Loss of mismatched HLA in leukemia after stem-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:478–88. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0811036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Villalobos IB, Takahashi Y, Akatsuka Y, et al. Relapse of leukemia with loss of mismatched HLA resulting from uniparental disomy after haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2010;115:3158–61. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-254284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wagner JE, Thompson JS, Carter SL, Kernan NA. Effect of graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis on 3-year disease-free survival in recipients of unrelated donor bone marrow (T-cell Depletion Trial): a multi-centre, randomised phase II-III trial. Lancet. 2005;366:733–41. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66996-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zorn E, Wang KS, Hochberg EP, et al. Infusion of CD4+ donor lymphocytes induces the expansion of CD8+ donor T cells with cytolytic activity directed against recipient hematopoietic cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:2052–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kircher B, Stevanovic S, Urbanek M, et al. Induction of HA-1-specific cytotoxic T-cell clones parallels the therapeutic effect of donor lymphocyte infusion. Br J Haematol. 2002;117:935–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marijt WA, Heemskerk MH, Kloosterboer FM, et al. Hematopoiesis-restricted minor histocompatibility antigens HA-1- or HA-2-specific T cells can induce complete remissions of relapsed leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:2742–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0530192100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giralt S, Hester J, Huh Y, et al. CD8-depleted donor lymphocyte infusion as treatment for relapsed chronic myelogenous leukemia after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 1995;86:4337–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alyea EP, Soiffer RJ, Canning C, et al. Toxicity and efficacy of defined doses of CD4(+) donor lymphocytes for treatment of relapse after allogeneic bone marrow transplant. Blood. 1998;91:3671–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takami A, Sugimori C, Feng X, et al. Expansion and activation of minor histocompatibility antigen HY-specific T cells associated with graft-versus-leukemia response. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2004;34:703–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.den Haan JM, Meadows LM, Wang W, et al. The minor histocompatibility antigen HA-1: a diallelic gene with a single amino acid polymorphism. Science. 1998;279:1054–7. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5353.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brickner AG, Warren EH, Caldwell JA, et al. The immunogenicity of a new human minor histocompatibility antigen results from differential antigen processing. J Exp Med. 2001;193:195–206. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.2.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.A map of human genome variation from population-scale sequencing. Nature. 2010;467:1061–73. doi: 10.1038/nature09534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Warren EH, Zhang XC, Li S, et al. Effect of MHC and non-MHC donor/recipient genetic disparity on the outcome of allogeneic HCT. Blood. 2012;120:2796–806. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-04-347286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murata M, Warren EH, Riddell SR. A human minor histocompatibility antigen resulting from differential expression due to a gene deletion. J Exp Med. 2003;197:1279–89. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Molldrem JJ, Lee PP, Wang C, et al. Evidence that specific T lymphocytes may participate in the elimination of chronic myelogenous leukemia. Nat Med. 2000;6:1018–23. doi: 10.1038/79526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rezvani K, Yong AS, Savani BN, et al. Graft-versus-leukemia effects associated with detectable Wilms tumor-1 specific T lymphocytes following allogeneic stem cell transplantation for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) Blood. 2007 doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-076844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Atanackovic D, Arfsten J, Cao Y, et al. Cancer-testis antigens are commonly expressed in multiple myeloma and induce systemic immunity following allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2007;109:1103–12. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-014480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McLarnon A, Piper KP, Goodyear OC, et al. CD8(+) T-cell immunity against cancer-testis antigens develops following allogeneic stem cell transplantation and reveals a potential mechanism for the graft-versus-leukemia effect. Haematologica. 2010;95:1572–8. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.019539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takahashi Y, Harashima N, Kajigaya S, et al. Regression of human kidney cancer following allogeneic stem cell transplantation is associated with recognition of an HERV-E antigen by T cells. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:1099–109. doi: 10.1172/JCI34409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Verheyden S, Schots R, Duquet W, Demanet C. A defined donor activating natural killer cell receptor genotype protects against leukemic relapse after related HLA-identical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Leukemia. 2005;19:1446–51. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hsu KC, Keever-Taylor CA, Wilton A, et al. Improved outcome in HLA-identical sibling hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation for acute myelogenous leukemia predicted by KIR and HLA genotypes. Blood. 2005;105:4878–84. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-12-4825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stringaris K, Adams S, Uribe M, et al. Donor KIR Genes 2DL5A, 2DS1 and 3DS1 are associated with a reduced rate of leukemia relapse after HLA-identical sibling stem cell transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia but not other hematologic malignancies. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16:1257–64. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hsu KC, Gooley T, Malkki M, et al. KIR ligands and prediction of relapse after unrelated donor hematopoietic cell transplantation for hematologic malignancy. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2006;12:828–36. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller JS, Cooley S, Parham P, et al. Missing KIR ligands are associated with less relapse and increased graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) following unrelated donor allogeneic HCT. Blood. 2007;109:5058–61. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-065383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cooley S, Trachtenberg E, Bergemann TL, et al. Donors with group B KIR haplotypes improve relapse-free survival after unrelated hematopoietic cell transplantation for acute myelogenous leukemia. Blood. 2009;113:726–32. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-171926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cooley S, Weisdorf DJ, Guethlein LA, et al. Donor selection for natural killer cell receptor genes leads to superior survival after unrelated transplantation for acute myelogenous leukemia. Blood. 2010;116:2411–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-05-283051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Venstrom JM, Pittari G, Gooley TA, et al. HLA-C-dependent prevention of leukemia relapse by donor activating KIR2DS1. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:805–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peruzzi M, Wagtmann N, Long EO. A p70 killer cell inhibitory receptor specific for several HLA-B allotypes discriminates among peptides bound to HLA-B*2705. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1585–90. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.4.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rajagopalan S, Long EO. The direct binding of a p58 killer cell inhibitory receptor to human histocompatibility leukocyte antigen (HLA)-Cw4 exhibits peptide selectivity. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1523–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.8.1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boyington JC, Motyka SA, Schuck P, Brooks AG, Sun PD. Crystal structure of an NK cell immunoglobulin-like receptor in complex with its class I MHC ligand. Nature. 2000;405:537–43. doi: 10.1038/35014520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fan QR, Long EO, Wiley DC. Crystal structure of the human natural killer cell inhibitory receptor KIR2DL1-HLA-Cw4 complex. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:452–60. doi: 10.1038/87766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baron F, Petersdorf EW, Gooley T, et al. What is the role for donor natural killer cells after nonmyeloablative conditioning? Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15:580–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu CJ, Yang XF, McLaughlin S, et al. Detection of a potent humoral response associated with immune-induced remission of chronic myelogenous leukemia. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:705–14. doi: 10.1172/JCI10196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bellucci R, Alyea EP, Chiaretti S, et al. Graft-versus-tumor response in patients with multiple myeloma is associated with antibody response to BCMA, a plasma-cell membrane receptor. Blood. 2005;105:3945–50. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-11-4463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bray RA, Hurley CK, Kamani NR, et al. National marrow donor program HLA matching guidelines for unrelated adult donor hematopoietic cell transplants. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008;14:45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kawase T, Morishima Y, Matsuo K, et al. High-risk HLA allele mismatch combinations responsible for severe acute graft-versus-host disease and implication for its molecular mechanism. Blood. 2007;110:2235–41. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-072405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shaw BE, Gooley TA, Malkki M, et al. The importance of HLA-DPB1 in unrelated donor hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 2007;110:4560–6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-095265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fleischhauer K, Shaw BE, Gooley T, et al. Effect of T-cell-epitope matching at HLA-DPB1 in recipients of unrelated-donor haemopoietic-cell transplantation: a retrospective study. Lancet Oncology. 2012;13:366–74. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70004-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kawase T, Matsuo K, Kashiwase K, et al. HLA mismatch combinations associated with decreased risk of relapse: implications for the molecular mechanism. Blood. 2009;113:2851–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-08-171934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shaw BE, Mayor NP, Russell NH, et al. Diverging effects of HLA-DPB1 matching status on outcome following unrelated donor transplantation depending on disease stage and the degree of matching for other HLA alleles. Leukemia. 2010;24:58–65. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Anasetti C, Logan BR, Lee SJ, et al. Peripheral-blood stem cells versus bone marrow from unrelated donors. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1487–96. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1203517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Deeg HJ, Spitzer TR, Cottler-Fox M, Cahill R, Pickle LW. Conditioning-related toxicity and acute graft-versus-host disease in patients given methotrexate/cyclosporine prophylaxis. Bone marrow transplantation. 1991;7:193–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Clift RA, Buckner CD, Appelbaum FR, et al. Allogeneic marrow transplantation in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in the chronic phase: a randomized trial of two irradiation regimens. Blood. 1991;77:1660–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mielcarek M, Martin PJ, Leisenring W, et al. Graft-versus-host disease after nonmyeloablative versus conventional hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2003;102:756–62. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-08-2628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rotta M, Storer BE, Storb R, et al. Impact of recipient statin treatment on graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16:1463–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rotta M, Storer BE, Storb RF, et al. Donor statin treatment protects against severe acute graft-versus-host disease after related allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 2010;115:1288–95. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-240358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Deeg HJ, Storer BE, Boeckh M, et al. Reduced incidence of acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease with the addition of thymoglobulin to a targeted busulfan/cyclophosphamide regimen. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2006;12:573–84. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Soiffer RJ, Lerademacher J, Ho V, et al. Impact of immune modulation with anti-T-cell antibodies on the outcome of reduced-intensity allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for hematologic malignancies. Blood. 2011;117:6963–70. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-332007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bashey A, Medina B, Corringham S, et al. CTLA4 blockade with ipilimumab to treat relapse of malignancy after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 2009;113:1581–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-168468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhou J, Bashey A, Zhong R, et al. CTLA-4 blockade following relapse of malignancy after allogeneic stem cell transplantation is associated with T cell activation but not with increased levels of T regulatory cells. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2011;17:682–92. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2443–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Brahmer JR, Tykodi SS, Chow LQ, et al. Safety and activity of anti-PD-L1 antibody in patients with advanced cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2455–65. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Maury S, Lemoine FM, Hicheri Y, et al. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cell depletion improves the graft-versus-tumor effect of donor lymphocytes after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:41ra52. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kwak LW, Taub DD, Duffey PL, et al. Transfer of myeloma idiotype-specific immunity from an actively immunised marrow donor. Lancet. 1995;345:1016–20. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90757-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cabrera R, Diaz-Espada F, Barrios Y, et al. Infusion of lymphocytes obtained from a donor immunised with the paraprotein idiotype as a treatment in a relapsed myeloma. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2000;25:1105–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Neelapu SS, Munshi NC, Jagannath S, et al. Tumor antigen immunization of sibling stem cell transplant donors in multiple myeloma. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2005;36:315–23. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sergeeva A, Alatrash G, He H, et al. An anti-PR1/HLA-A2 T-cell receptor-like antibody mediates complement-dependent cytotoxicity against acute myeloid leukemia progenitor cells. Blood. 2011;117:4262–72. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-07-299248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rousseau RF, Biagi E, Dutour A, et al. Immunotherapy of high-risk acute leukemia with a recipient (autologous) vaccine expressing transgenic human CD40L and IL-2 after chemotherapy and allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2006;107:1332–41. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ho VT, Vanneman M, Kim H, et al. Biologic activity of irradiated, autologous, GM-CSF-secreting leukemia cell vaccines early after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:15825–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908358106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Riddell SR, Watanabe KS, Goodrich JM, Li CR, Agha ME, Greenberg PD. Restoration of viral immunity in immunodeficient humans by the adoptive transfer of T cell clones. Science. 1992;257:238–41. doi: 10.1126/science.1352912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rooney CM, Smith CA, Ng CY, et al. Use of gene-modified virus-specific T lymphocytes to control Epstein-Barr-virus-related lymphoproliferation. Lancet. 1995;345:9–13. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91150-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Leen AM, Myers GD, Sili U, et al. Monoculture-derived T lymphocytes specific for multiple viruses expand and produce clinically relevant effects in immunocompromised individuals. Nature medicine. 2006;12:1160–6. doi: 10.1038/nm1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hanley PJ, Cruz CR, Savoldo B, et al. Functionally active virus-specific T cells that target CMV, adenovirus, and EBV can be expanded from naive T-cell populations in cord blood and will target a range of viral epitopes. Blood. 2009;114:1958–67. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-213256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Heemskerk MH, Hoogeboom M, Hagedoorn R, Kester MG, Willemze R, Falkenburg JH. Reprogramming of virus-specific T cells into leukemia-reactive T cells using T cell receptor gene transfer. J Exp Med. 2004;199:885–94. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cooper LJ, Al-Kadhimi Z, Serrano LM, et al. Enhanced antilymphoma efficacy of CD19-redirected influenza MP1-specific CTLs by cotransfer of T cells modified to present influenza MP1. Blood. 2005;105:1622–31. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Micklethwaite KP, Savoldo B, Hanley PJ, et al. Derivation of human T lymphocytes from cord blood and peripheral blood with antiviral and antileukemic specificity from a single culture as protection against infection and relapse after stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2010;115:2695–703. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-09-242263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kochenderfer JN, Wilson WH, Janik JE, et al. Eradication of B-lineage cells and regression of lymphoma in a patient treated with autologous T cells genetically engineered to recognize CD19. Blood. 2010;116:4099–102. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-281931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Savoldo B, Ramos CA, Liu E, et al. CD28 costimulation improves expansion and persistence of chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells in lymphoma patients. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:1822–6. doi: 10.1172/JCI46110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Porter DL, Levine BL, Kalos M, Bagg A, June CH. Chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells in chronic lymphoid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:725–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Brentjens RJ, Riviere I, Park JH, et al. Safety and persistence of adoptively transferred autologous CD19-targeted T cells in patients with relapsed or chemotherapy refractory B-cell leukemias. Blood. 2011;118:4817–28. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-04-348540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kochenderfer JN, Dudley ME, Feldman SA, et al. B-cell depletion and remissions of malignancy along with cytokine-associated toxicity in a clinical trial of anti-CD19 chimeric-antigen-receptor-transduced T cells. Blood. 2012;119:2709–20. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-10-384388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kochenderfer JN, Dudley ME, Maric I, et al. Dramatic Regression of Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia in the First Patient Treated With Donor-Derived Genetically-Engineered Anti-CD19-Chimeric-Antigen-Receptor-Expressing T Cells After Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2011;17:S158. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Provasi E, Genovese P, Lombardo A, et al. Editing T cell specificity towards leukemia by zinc finger nucleases and lentiviral gene transfer. Nat Med. 2012;18:807–15. doi: 10.1038/nm.2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]