Abstract

Kaposi’s sarcoma associated herpesvirus (KSHV) is the human oncovirus which causes Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS), a highly vascularised tumour originating from lymphatic endothelial cells. Amongst others, the dimeric complex formed by the KSHV virion envelope glycoproteins H and L (gH/gL) is required for entry of herpesviruses into the host cell. We show that the Ephrin receptor tyrosine kinase A2 (EphA2) is a cellular receptor for KSHV gH/gL. EphA2 co-precipitated with both gH/gL and KSHV virions. KSHV infection rates were increased upon over-expression of EphA2. In contrast, antibodies against EphA2 and siRNAs directed against EphA2 inhibited KSHV infection of lymphatic endothelial cells. Pretreatment of KSHV virions with soluble EphA2 resulted in a dose-dependent inhibition of KSHV infection by up to 90%. Similarly, pretreating cells with the soluble EphA2 ligand EphrinA4 but not with EphA2 itself impaired KSHV infection. Notably, deletion of the EphA2 gene essentially abolished KSHV infection of murine vascular endothelial cells. Binding of gH/gL to EphA2 triggered EphA2 phosphorylation and endocytosis, a major pathway of KSHV entry. Quantitative RT-PCR and situ histochemistry revealed a close correlation between KSHV infection and EphA2 expression both in cultured cells derived from KS or lymphatic endothelium and in KS specimens, respectively. Taken together, these results identify EphA2, a tyrosine kinase with known functions in neo-vascularisation and oncogenesis, as receptor for KSHV gH/gL and implicate an important role for EphA2 in KSHV infection especially of endothelial cells and in KS.

Introduction

Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) is the causative agent of Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS) and of two lymphoid malignancies 1–3. Entry of herpesviruses into host cells is seen as a multistep process that involves at least four viral glycoproteins and several cellular receptors 4, reviewed in 5. For the first step - attachment to the cytoplasma membrane - the ubiquitous cell surface heparan sulphate (HS) is utilised by KSHV glycoproteins gpK8.1 6, 7, gB 8, gH 9 and ORF4 10. However, many B-cells do not express HS at sufficient levels 11. It has been reported that KSHV binding to B-cells, macrophages and dendritic cells is mediated by DC-SIGN (CD209), instead of HS 12, 13. Binding of virion envelope glycoproteins to cell surface receptors is followed by the induction of cellular signalling pathways and entry of the virion into the cell reviewed in 5. For both steps, the interaction of KSHV gB with several integrins (α3β1, αVβ3, αVβ5) has been shown to play an important role 14–17. By binding to integrins, KSHV induces focal adhesion kinase FAK) phosphorylation which is followed by the activation of downstream molecules like Src, PI-3K and Akt 16, 18. The latter all play a role in triggering endocytosis, the main pathway of KSHV-entry into a variety of cells including endothelial cells 19, 20. As KSHV seems to enter most cells via endocytosis, release of the capsid by lipid membrane fusion takes place after internalization. Initially, the cysteine transporter xCT was identified as a potent fusion receptor for KSHV 21. However, the viral glycoproteins responsible for interactions with xCT, if any, have not been identified. In the case of KSHV, gB and gH/gL seem to comprise the minimal fusion machinery 22. Only few data exist on the function of gH and gL in KSHV entry. We reported that gH and the complex gH/gL bind to an unknown receptor on HS-negative sog9 cells 9. We now show that this protein is the Ephrin receptor A2 (EphA2), a tyrosine kinase contributing to neo-vascularisation and oncogenesis23,24–26, and demonstrate that EphA2 plays a pivotal role for KSHV infection of cells of endothelial origin.

RESULTS

KSHV envelope glycoproteins gH/gL bind to EphA2

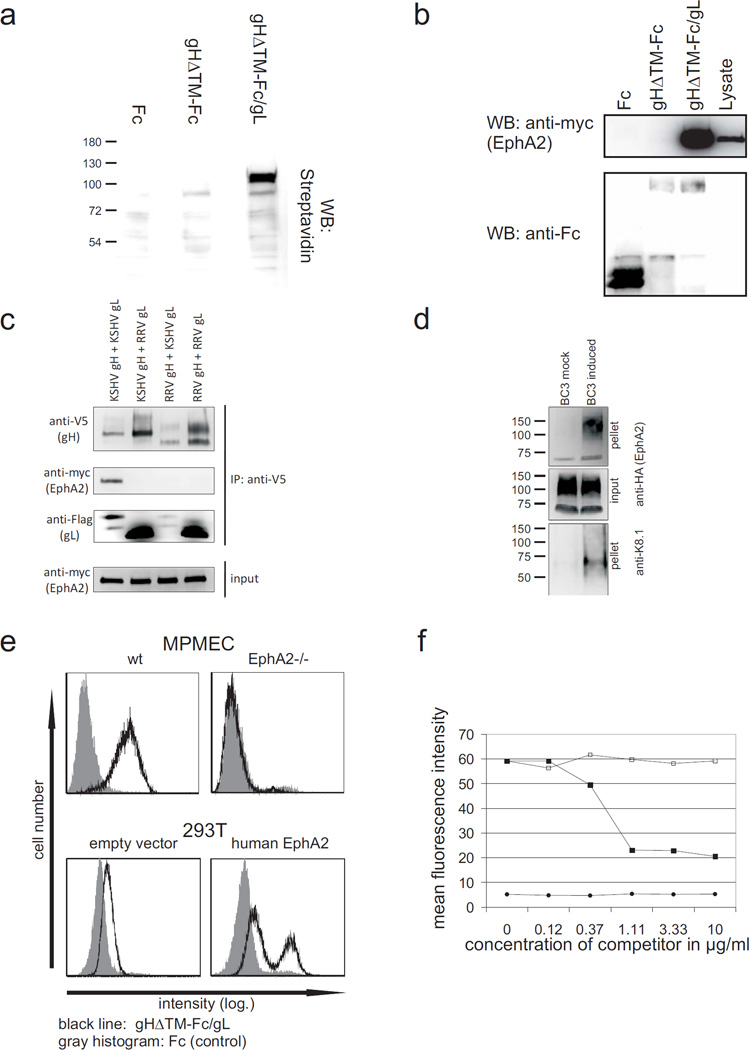

To identify the cellular receptor for gH/gL, sog9 cells 27 were surface biotinylated followed by immunoprecipitation using soluble gH lacking both the cytoplasmic and transmembrane regions fused to the Fc part of human IgG co-expressed with gL (gHΔTM-Fc/gL). A cellular membrane protein with an apparent molecular weight of 110 kDa was precipitated with the gH/gL complex, but not with gH alone (Fig. 1a). Mass spectrometry analysis including peptide sequencing unequivocally identified murine Ephrin receptor tyrosin kinase A2 (EphA2, Swissprot: Q03145) as the interacting protein (supplementary table). Immunoprecipitation with gHΔTM-Fc/gL from 293T cells transfected with an expression plasmid for myc-tagged soluble human EphA2 (pEphA2ΔICmychis) confirmed the interaction with human EphA2 (Fig. 1b). To further confirm the specificity of EphA2 binding for KSHV gH/gL and to exclude any influence of the Fc-part, similar immunoprecipitation experiments were performed using recombinant gH labelled with the short (14 aa) V5 tag. In addition, expression plasmids for gH and gL from the closely related rhesus monkey rhadinovirus (RRV) were included as controls. Although KSHV gL bound comparably well to both KSHV and RRV gH and vice versa (Fig. 1c, 3rd panel), only the complex formed by KSHV glycoproteins was able to precipitate EphA2 (Fig. 1c, 2nd panel). Thus, cellular EphA2 is efficiently and specifically precipitated by the KSHV glycoprotein complex gH/gL, but not by KSHV gH alone or by KSHV gH complexed with the closely related gL from RRV. In theory, gH/gL could be associated with other viral glycoproteins in the virion envelope such that the EphA2 binding site is not accessible. Thus, co-sedimentation experiments were performed using KSHV virions concentrated from the supernatant of the KSHV-positive PEL cell line BC3. The recombinantly expressed HA-tagged ectodomain of EphA2 was incubated with pre-cleared supernatant from BC3 cells that were either induced to produce KSHV virions or left uninduced (mock). KSHV virions were then pelleted by centrifugation and subjected to western blot analysis. The virion envelope protein gpK8.1 does not bind directly to EphA2 (data not shown). Therefore, cosedimentation of gpK8.1 and EphA2 demonstrates that both proteins are associated with viral particles (Fig 1d, right). Having shown that soluble EphA2 is able to bind to both isolated gH/gL (Fig. 1b and 1c: co-immunoprecipitation, Suppl. Fig. 1: FACS) as well as KSHV (Fig. 1d) we next examined whether gH/gL is able to bind to membrane-bound EphA2. Murine pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells (MPMEC) from either an EphA2 knock out mouse 28 or the parental mouse strain (wt) were incubated with gHΔTM-Fc/gL in the presence of heparin (Fig. 1e, top, black line). FITC labelled antihuman IgG was used to detect binding of gHΔTM-Fc/gL to the cells by FACS. Fc protein served as a negative control (Fig 1e, grey histogram). Whereas binding of gHΔTM-Fc/gL to wt MPMECs was clearly detectable, MPMEC from the EphA2 knock-out mouse were completely negative for binding (Fig. 1e, top right panel). The human cell lines examined in the context of this study expressed detectable levels of EphA2, albeit to a very variable extent (not shown and Suppl. Fig. 6). Thus, the same FACS analysis was performed using the human cell line 293T transfected with either an expression construct for full-length EphA2 or empty vector (Fig. 1e, bottom). Transfection of the EphA2 expression plasmid greatly increased binding of gHΔTM-Fc/gL to the surface of transfected cells (Fig. 1e, bottom right). Furthermore, competition with soluble EphA2-Fc was able to reduce the interaction of gHΔTM-Fc/gL with the cell surface in a dose-dependent manner up to threefold (Fig. 1f). This finding is particularly remarkable since both gH alone as well as the gH/gL complex bind to cell surface heparan sulphates with high affinity 9.

Fig. 1. KSHV gH/gL binds to human EphA2.

(a) KSHV gH/gL precipitates a membrane protein of approximately 110 kDa. Membrane proteins of sog9 mouse fibroblasts were biotinylated and precipitated with the denoted proteins bound to protein-A sepharose. Horseradish peroxidase coupled to streptavidin was used to detect precipitated membrane proteins. (b, c) KSHV gH/gL precipitates EphA2. 293T cells were transfected with an expression plasmid for myc-tagged human EphA2. The cells were lysed and precipitated with (b) protein-A-immobilized Fc, gHΔTM-Fc or gHΔTM-Fc/gL or (c) V5 tagged KSHV or RRV 26–95 gH in combination with KSHV or RRV 26–95 gL (Flag tag) immoblised to protein-G via anti-V5 antibodies. Precipitates were washed and subjected to Western blot analysis. (d) EphA2 co-sediments with KSHV. Pre-cleared and 10× concentrated supernatant from either lytically induced or mock-treated BC3 cells was incubated with supernatant from 293T cells expressing the HA-tagged soluble ectodomain of EphA2. KSHV virions were then pelleted by centrifugation, washed twice with PBS and subjected to PAGE and immunoblot with either anti-HA to detect EphA2 or anti-K8.1 to detect KSHV. (e) KSHV gH/gL binding to cells is mediated by EphA2. Cells were incubated with either Fc-protein (grey histogram) or gHΔTM-Fc/gL (black line). Heparin was added at 100 units/ml to inhibit binding of gH/gL to heparan sulphate. Anti-human IgG coupled to FITC was used as a secondary antibody and detected by FACS. Upper panel: MPMECs from EphA2−/− mice or the parental strain (wt) that were detached by brief treatment with trypsin. lower panel: 293T cells either transfected with an EphA2 expression construct (right) or empty vector (left). (f) Binding of soluble gHΔTM-Fc/gL to 293T cells was blocked with soluble EphA2-Fc. 293T cells were incubated with supernatants from cells expressing either soluble gHΔTM-FcStrep/gL (squares) or FcStrep-protein (circles). Either solEphA2-Fc (filled symbols) or Fc (unfilled squares) was added to the protein solutions in increasing concentration 30 min before incubation with 293T cells. Binding of the Strep-tagged proteins was determined by FACS.

Dose-dependent inhibition of KSHV infection by soluble EphA2

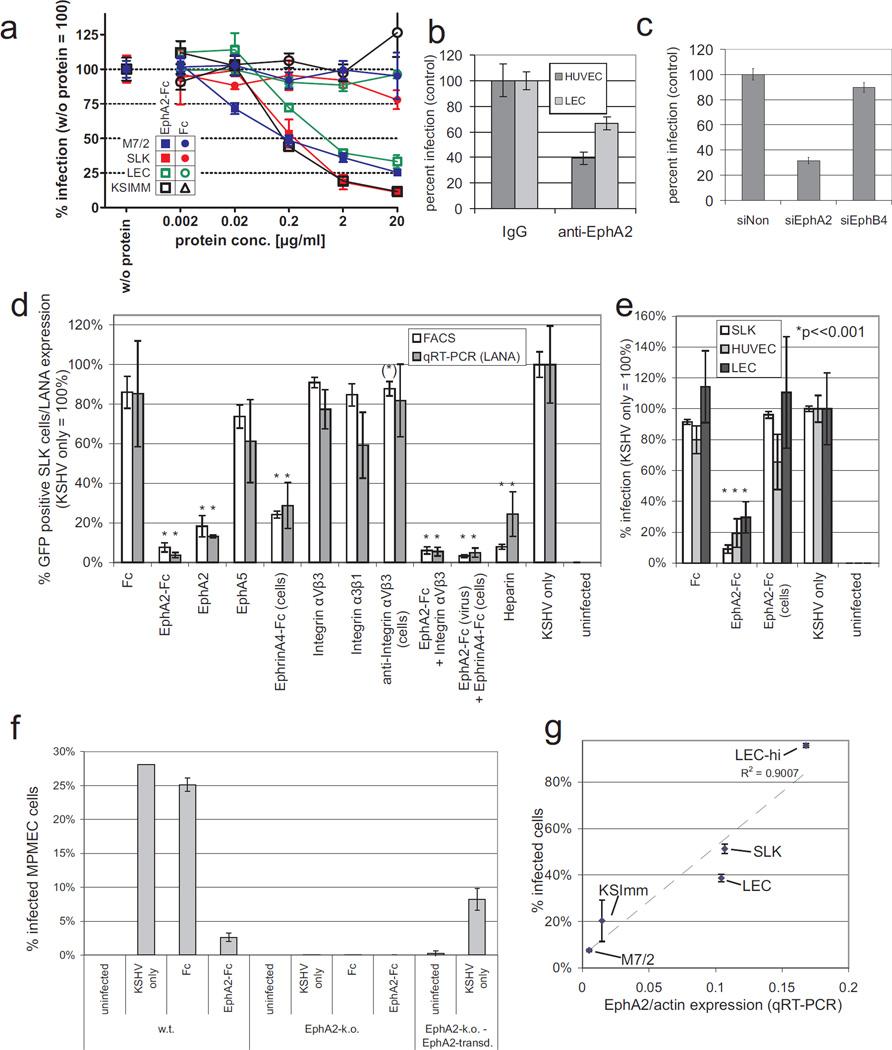

This raised the question whether EphA2 influences susceptibility to KSHV infection. Endothelial cells are considered natural targets of KSHV infection especially in KS lesions and have been reported to express EphA2 both in KS and in unafflicted tissues 29. In an experimental ‘loss-of-function’ setting, rKSHV.219 30 preparations were incubated with increasing amounts of soluble EphA2 (EphA2-Fc) prior to infection of human lymphatic endothelial cells (LEC), primary KS spindle cell cultures (M7/2 31) and two established KS cell lines (KSIMM 32, SLK 33). KSHV infection of these cell types is generally latent and non-productive. As rKSHV.219 carries the gene for green fluorescent protein (GFP) under the control of a constitutively active promoter, latent infection could be monitored by GFP expression. Notably, solEphA2-Fc inhibited KSHV infection dose dependently by up to 97%. Results from FACS-analysis of 6 (SLK) or 3 (M7/2, KSIMM, LEC) independent experiments per cell type are given in figure 2a. Fluorescence microscopy of one representative experiment using SLK cells is shown in supplementary figure 2. Half-maximal inhibition of KSHV infection was achieved at a concentration of less than 0.2 µg/ml which corresponds to approximately 1 nM of dimeric EphA2-Fc (Fig. 2a). Pre-incubation with soluble Fc alone (Fig. 2a, open squares) did not influence KSHV infection. Similar data as shown for cells of endothelial origin in Fig. 2a were obtained with the epithelial cell line 293T: 80% inhibition of KSHV infection were achieved by solEphA2-Fc at a concentration of 2µg/ml. Fc-protein alone (Suppl. Fig 3a) or gHΔTM-Fc (data not shown) did not influence KSHV infection. A GFP-expressing recombinant herpesvirus saimiri clone (HVS M45) was used as a control. Permissiveness of 293T cells for HVS infection was not affected by soluble EphA2 (Suppl. Fig. 3a).

Fig. 2. Permissiveness for KSHV infection correlates with EphA2 expression in cell culture.

(a) Dose-dependent inhibition of KSHV infection by soluble EphA2. Primary LEC (green), two cell lines derived from KS (SLK:red, KSImm:black) and spindle cells derived from a KS biopsy (M7/2: blue) were infected with KSHV.219 at an SLK-MOI of 0.5 (SLK, KSImm, M7/2) or 0.2 (LEC). Prior to infection, each virus was incubated with either solEphA2-Fc (squares) or Fc (control, circles) for 30 min at the indicated concentrations. GFP-positive cells were detected by FACS 3 days after infection. The infection rate achieved in the absence of either protein (solEphA2-Fc or Fc) was set to 100 which corresponded to approx 15% - 40% infected cells depending on cell type (n=6 for SLK and KSImm, n=3 for LEC and M7/2, error bars represent sd). (b) Antibodies to EphA2 inhibit KSHV infection in primary HUVEC and LEC. HUVEC (dark grey) and LEC (light grey) cells were incubated with antibody to EphA2 or rabbit IgG at 1 mg/ml and infected as described in (b) (n=7, error bars represent sem). (c) siRNAs against EphA2 inhibit KSHV infection of LECs. LECs were transfected with either a non-targeting siRNA (siNon), an siRNA pool against EphA2 (siEphA2) or against the related EphB4 (siEphB4) two days prior to infection with rKSHV.219. The relative percentage of GFP-expressing cells is shown (siNon = 100%, n=4, error bars represent sem). (d) Effect of soluble proteins and heparin on KSHV infection of SLK cells. SLK cells were infected with KSHV.219 at an MOI of 0.5. Prior to infection, virus or – where indicated – the cells were incubated with the indicated protein(s). A concentration of 2 µg/ml was used except for integrins and anti-integrin αVβ3 (10µg/ml). Heparin was used at a concentration of 166 IU/ml. KSHV infection was determined on day 3 p.i. by both FACS for GFP-positive cells and qRT-PCR for LANA expression normalized to GAPDH. Values achieved in the presence of KSHV only were set to 100 % (infection rate by FACS: 44.3%). Mean and sd from 6 (FACS) or 3 (qPCR) independent experiments are shown. Error bars represent sd, asterisks indicate statistically significant differences to KSHV only (*:p < 0.001; (*): p < 0.01). (e) Inhibition of KSHV by EphA2 requires contact of EphA2 with the virus. Cells of endothelial origin (SLK, HUVEC, LEC) were infected with KSHV.219 at an SLK-MOI of 0.5. Prior to infection, either the viral inoculum or the cells were incubated with EphA2-Fc (2 µg/ml, 30 min, 37°C) or left untreated. Fc-protein was used as a control. KSHV infection was determined on day 3 by FACS. Mean and sd of relative infection (KSHV only = 100%) from 3 independent experiments are shown. Error bars represent sd, asterisks indicate statistically significant differences to KSHV only (p < 0.001). (f) Loss of EphA2 expression renders MPMEC resistant to KSHV infection. MPMEC cells from either wild type (w.t) or an EphA2 knock-out (EphA2-k.o.) mouse were infected with KSHV (SLK-MOI: 2). EphA2-k.o. cells transduced with a retroviral vector expressing murine EphA2 were infected as a control (right). Where indicated, KSHV was incubated with EphA2-Fc or control protein prior to infection (2 µg/ml, 30min). Mean and sd from 3 independent experiments are shown. (g) Susceptibility for KSHV infection correlates with EphA2 expression in KS cells and lymphatic endothelium. Human cells and cell lines derived from KS (M7/2, KSImm, SLK) or two different batches of human lymphatic endothelial cells (LEC, LEC-hi) were infected with KSHV at constant cell/virus ratio corresponding to an MOI of approx. 0.5 on SLK cells. Cells were harvested 2 days p.i., infection was determined by FACS and both EphA2 and actin mRNA were quantified by qRT-PCR. The quotient of mRNA expressions (EphA2/actin) is plotted on the x-axis against the percentage of KSHV infected cells on the y-axis (R2 = square correlation coefficient, n=6 for SLK and KSImm, 3 for LEC, LEC-hi and M7/2).

KSHV infection is inhibited by antibodies against EphA2 and knock-down of EphA2 expression

In addition to blocking the EphA2 binding site(s) on KSHV virions with soluble EphA2-Fc, a polyclonal antibody against EphA2 was used to block intrinsically expressed EphA2 on HUVEC and LEC cells prior to KSHV infection. It resulted in a significant reduction of KSHV infection (Fig. 2b, p < 0.05). Infection of 293T cells with KSHV but not HVS could also be inhibited by pre-incubation of the cells with a polyclonal antibody against EphA2 (Suppl. Fig. 3b), and overexpression of EphA2 in two human cell lines resulted in increased KSHV infection (Suppl. Fig. 4). The functional relevance of EphA2 in infection of endothelial cells could be confirmed by RNA-interference (Fig. 2c). A pool of four siRNAs (Dharmacon) was used to efficiently knock-down EphA2 expression in LECs. Silencing of EphA2 was verified by FACS analysis (Suppl. Fig. 5), which confirms both the specificity of our polyclonal antibody and the efficacy of the siRNA pool. The siRNA pool against EphA2, but not the siRNA pool against the related EphB4 receptor or a non-targeting siRNA, reduced the susceptibility of LEC to KSHV infection by approximately 70% (siNon vs. siEphA2, student’s t-test, p < 0.05). In summary, both soluble EphA2-Fc, an antibody against EphA2 and knock-down of EphA2 expression resulted in a marked reduction of KSHV infection in endothelial cells and cell lines.

Inhibition of KSHV infection is specific for EphA2 and requires interaction with the virion

To further elucidate the specificity of these effects for EphA2/virion interaction, additional experiments were performed using 1) soluble EphA2 without the Fc tag to exclude that the observed effect was all or in part due to binding of the Fc part, 2) the closely related protein EphA5, 3) the soluble ligand EphA4-Fc which induces EphA2 signalling, 4) pre-incubation of the cells instead of KSHV with EphA2 and 5) soluble integrins and heparin for comparison. The results are summarized in figures 2d and 2e. SLK cells were infected with KSHV.219 at an MOI of 0.5. Infection rates were determined both by FACS analysis for GFP-expression and by quantitative real time-PCR (qRT-PCR) for the latently expressed LANA-1 transcript. Relative values from 6 (GFP) or 3 (qRT-PCR) independent experiments are shown with values from KSHV infected cells without blocking agent set to 100%. As in figure 2a, pre-incubation of KSHV with EphA2-Fc (2 µg/ml) resulted in a marked reduction of infection (approx. 90%) which was comparable to the known attachment-blocker heparin. This effect was also observed when soluble EphA2 was used instead of soluble EphA2-Fc. However, the closely related EphA5 did not significantly reduce KSHV infection. In contrast, pre-incubation of the cells with the soluble ligand EphrinA4-Fc did also block infection, albeit to a lesser extent than EphA2-Fc. Simultaneous pre-treatment of KSHV with EphA2-Fc and of the cells with EphrinA4-Fc did not result in enhanced reduction compared to EphA2-Fc pre-treatment only. Surprisingly, pre-incubation of KSHV with integrin-α3β1 or -αVβ3 did not result in a statistically significant reduction of infection. Only pre-treatment of SLK cells with the blocking antibody LM609 directed against integrin αVβ3 resulted in a moderately significant reduction of KSHV infection when determined by FACS-analysis. In summary, the data show that the observed inhibition of KSHV infection is specific for EphA2. However, it remained to be shown that this inhibitory effect is mediated by the interaction of EphA2-Fc with the KSHV virion and not the cell. Thus, either KSHV or the cells were incubated with EphA2-Fc 30 min prior to infection. Soluble Fc was used as a control. Compared to both Fc pre-treatment or the buffer control (KSHV only), only pre-treatment of the viral inoculum with EphA2-Fc at 2 µg/ml resulted in a statistically significant reduction of KSHV infection. In contrast to the EphA2 ligand EphrinA4-Fc, soluble EphA2-Fc did not result in reduced infection when added to the cells (Fig. 2e). This shows that inhibition of infection by EphA2 requires the interaction of EphA2 with the KSHV virion. The EphA2 or EphA2-Fc competition experiments shown hiterhto resulted in a reduction of KSHV infection by approximately 70% to 95%, depending on cell type. This incomplete block of infection could be due to the fact that infection pathways independent from the interaction of gH/gL with EphA2 or putative alternative ligands exist. However, it could also be due to incomplete or reversible binding of EphA2 to KSHV. The data shown in figure 2a argue against an incomplete saturation of EphA2 binding sites after 30 min of incubation at room temperature, as increasing the EphA2-Fc concentration to 20 µg was barely accompanied by a further decrease of KSHV infection. As soluble EphA2 did not significantly inhibit attachment of KSHV to the cell (data not shown), partial release of EphA2 from EphA2-blocked KSHV particles attached to the cytoplasma membrane will inevitably occur, as the binding of EphA2 to gH/gL is certainly non-covalent. As a result, binding sites for intrinsic EphA2 will become available again on KHSV. Thus, the relevance of EphA2 for the infection is likely to be underestimated by the ‘loss of function’ experiments shown here with human cells.

EphA2 is crucial for KSHV infection of endothelial cells

Experiments using cells completely lacking EphA2 expression would certainly provide more robust data on the relevance of EphA2 for KSHV infection. However, only murine EphA2 knock-out cells are available. KSHV is able to infect rodent cells albeit with a lower efficacy 34. As we showed initially that KSHV gH/gL binds to both human and murine EphA2, we first tested whether soluble EphA2-Fc interferes with the infection of murine cells, too. Murine pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells (MPMEC) were infected with KSHV.219 at an infectious particle per cell ratio of 3. Infection was measured via FACS analysis for GFP-expression 3 days later. About 25% of the MPMEC cells were positive for GFP expression. Incubation of the viral inoculum with soluble EphA2-Fc at 2 µg/ml for 30 min prior to infection reduced the infection by about 90% (Fig. 2f). Pre-incubation with soluble Fc did not significantly alter KSHV infection. Notably, MPMECs from an EphA2 knock-out mouse were almost completely resistant to KSHV infection (Fig. 2f, middle). As a control, MPMEC from the EphA2 −/− mouse were transduced with a retroviral vector expressing murine EphA2. Although these transduced cells expressed EphA2 at a low level not exceeding 5 – 10% of the EphA2 expressed from w.t. MPMEC (data not shown), they regained permissiveness for KSHV infection (Fig. 2f, right).

Although many cell lines can be infected by KSHV, their permissiveness for KSHV entry and infection varies considerably 35 as does the expression of EphA2. EphA2 RNA expression levels were measured by quantitative RT-PCR in 10 different human cells and cell lines and normalized to actin mRNA levels. All cells were infected at a constant MOI (0.5 on SLK cells). Soluble EphA2-Fc at a concentration of 2 µg/ml diminished KSHV infection in all 10 cell types examined by at least 50% (Suppl. Fig. 6). Plotting the EphA2/actin mRNA ratio against the percentage of infected cells revealed a linear correlation (RPearson = 0.95, p = 0.014) for all cells derived from lymphatic endothelium, i.e. primary LEC and cells or cell lines derived from KS (Fig. 2g). Most notably, the permissiveness of two different batches of LECs varied about 2-fold (LEC and LEC-hi) which was reflected by different EphA2 mRNA levels.

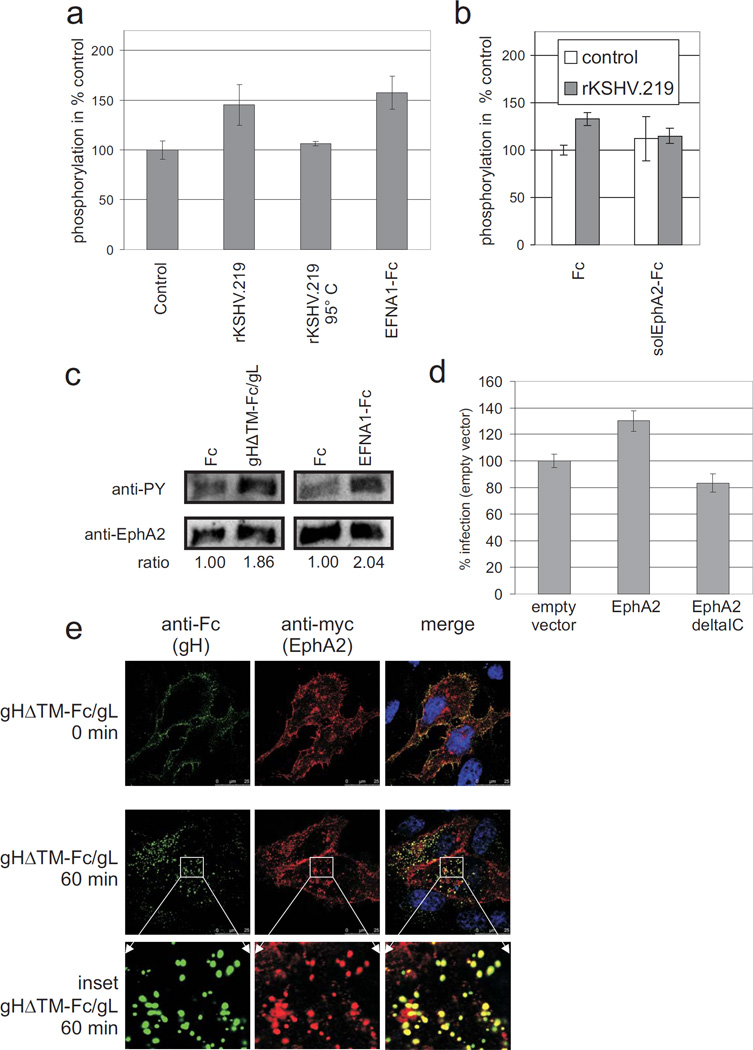

Binding of gH/gL to EphA2 triggers EphA2 phosphorylation and endocytosis

Binding of Ephrin receptors to their ligands induces receptor clustering, autophosphorylation and activation of kinase activity (reviewed in 36). This raised the question whether KSHV binding also results in increased autophosphorylation of EphA2. 293T cells were incubated with concentrated supernatants either from 293 cells producing recombinant KSHV strain rKSHV.219 or from uninfected 293 cells. Using a phospho-EphA2 ELISA (R&D Systems), increased autophosphorylation was detectable within 10 minutes of incubation with rKSHV.219 (Fig. 3a). Interestingly, stimulation with soluble EphrinA1 (EFNA1-Fc), a natural ligand of EphA2, was barely more effective than stimulation with KSHV (Fig. 3a). This effect was specifically reverted by addition of soluble EphA2-Fc protein, but not by addition of Fc control protein (Fig. 3b). Next, soluble gHΔTM-Fc/gL was used to stimulate EphA2 phosphorylation. This revealed that crosslinking of gHΔTM-Fc/gL through an anti-Fc antibody was required for activation of EphA2. Cross-linking mimics the higher-order clustering of envelope glycoproteins on intact virions. Stimulation of serum starved cells with cross-linked soluble gHΔTM-Fc/gL or EFNA1-Fc resulted in an approximately 2-fold increase of EphA2 phosphorylation as detected by Western blot (Fig. 3c). To determine whether these effects are of biological significance for KSHV entry, we transiently overexpressed either full-length EphA2 or EphA2 without the intracellular kinase domain in 293T cells. Similar surface expression was verified by FACS analysis (not shown). Only EphA2 with intact kinase domain enhanced KSHV infection (Fig. 3d).

Fig. 3. KSHV or gH/gL trigger tyrosine phosphorylation and endocytosis of EphA2.

(a,b) KSHV triggers tyrosine phosphorylation of EphA2. (a) 293T cells were incubated for 10 min with concentrated rKSHV.219 (n = 5), heat-inactivated rKSHV.219 (5 min 95°C, n = 2) or a negative control prepared identically from the supernatant of KSHV-negative 293 cells (n = 5). EFNA1-Fc at a final concentration of 5 µg/ml served as a positive control (n = 5). EphA2 phosphorylation was determined by phospho-EphA2 ELISA (R&D Systems). Optical densities obtained after incubation with the KSHV-negative control preparation were set to 100%. Arithmetic mean and standard deviation are shown. Only the differences between control and rKSHV.219 (p < 0.005) or EFNA1-Fc (p < 0.005) were statistically significant (Student’s t-test). (b) 293T cells were stimulated with either rKSHV.219 (grey bars) or a KSHV-negative control preparation (white bars) as in (a). In addition, Fc or solEphA2-Fc were added to the preparations at a final concentration of 5 µg/ml 30 min prior to incubation with the cells. EphA2 phosphorylation was determined by ELISA. Relative mean values (control preparation with Fc-protein = 100%) and standard deviation from three independent experiments are shown. Differences in EphA2 phosphorylation between control and rKSHV.219 were significant for Fc (p < 0.005), but not for solEphA2-Fc (p = 0.85). Reduction of KSHV-induced EphA2 phosphorylation by pre-incubation of KSHV with solEphA2-Fc was significant (p < 0.05). (c) gH/gL triggers tyrosine phosphorylation of EphA2. Serum starved 293T cells were stimulated for 10 min with gHΔTM-Fc/gL or Fc (1.5 µg/ml) cross-linked via anti-Fc monoclonal antibody. EphA2 was immunoprecipitated and assayed for tyrosine phosphorylation by western blotting and detection with anti-phosphotyrosine monoclonal antibody followed by detection of EphA2 for normalization. (d) The intracellular domain of EphA2 is required to enhance KSHV infection of 293T cells. 293T cells were transiently transfected with either empty vector, an expression plasmid for EphA2 or an EphA2 variant lacking the intracellular domain (EphA2deltaIC). The cells were then infected with rKSHV.219 and the rate of infection was quantified and normalized to empty vector control (n=3, error bars represent sd). (e) gH/gL and EphA2 colocalise after endocytosis. gHΔTM-Fc/gL was first preincubated and crosslinked for 30 min with anti-human-Fc-Alexa488 antibody. HELA cells that were transfected with an EphA2myc expression plasmid two days before were then incubated with the crosslinked gHΔTM-Fc/gL for 1h at 4°C, then washed, shifted to 37°C and fixed with 3% PFA after 0 min (first row) or 60 min at 37°C (2nd row, enlarged insets are shown in row 3). EphA2myc was detected with primary monoclonal 9E10 anti-myc-epitope antibody and anti-mouse-Cy3 secondary antibody. Cells were visualized by sequential confocal laser scanning microscopy.

The mechanism through which EphA2 contributes to KSHV infection might be – apart from providing a high affinity cellular binding receptor and the initiation of signaling - triggering of endocytosis and thus viral entry. To ascertain whether EphA2 is able to mediate uptake of gHΔTM-Fc/gL, myc-epitope tagged EphA2 was transiently expressed in Hela cells. The cells where then incubated with cross-linked gHΔTM-Fc/gL at 4°C before analysing the localization of both proteins by immunofluorescence via either the Fc-part (gHΔTM-Fc/gL) or the myc-tag (EphA2). Directly after incubation at 4°C, EphA2 and gHΔTM-Fc/gL colocalized at the membrane (Fig. 3e, top panel), whereas after a shift to 37°C for 60 min gHΔTM-Fc/gL and EphA2 colocalized at vesicular structures within the cell (Fig. 3e, middle panel and enlarged insets, bottom panel). Additional experiments were performed to confirm that gHΔTM-Fc/gL enters the cell via endocytosis. Cross-linked gHΔTM-Fc/gL, EFNA1-Fc or Fc were allowed to bind to heparan sulphate deficient sog9 cells for 1 hour at 4°C. Shifting the temperature to 37°C was followed by efficient uptake of both EFNA1-Fc (Suppl. Fig. 7, top panel) and gHΔTM-Fc/gL (Suppl. Fig. 7, middle panel), but not Fc (Suppl. Fig. 7, bottom panel). The observed relocalization from the plasma membrane to a perinuclear area could be inhibited by addition of the endocytosis inhibitor phenylarsine oxide (PAO, Suppl. Fig. 7, right).

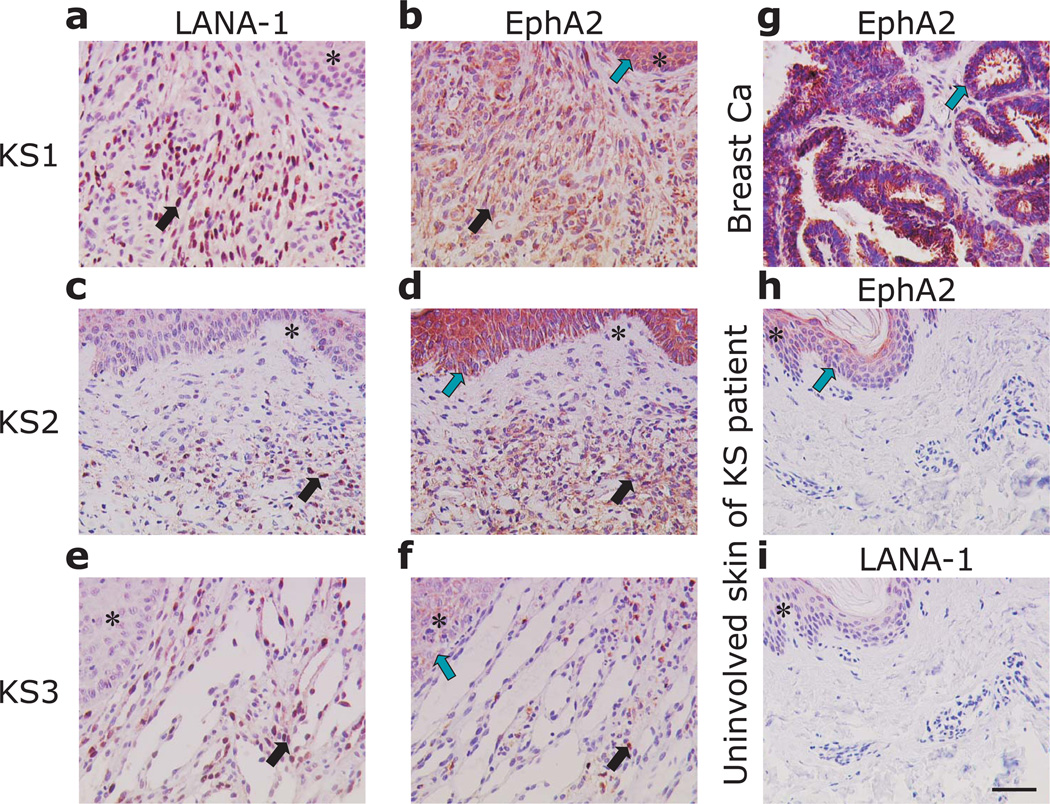

EphA2 is highly expressed in KS lesions but not in uninvolved skin

The close correlation between EphA2 expression and susceptibility to KSHV infection that we observed for cells and cell lines derived from lymphatic endothelium (Fig. 2g) led us to examine the expression of EphA2 and KSHV infection in tissue sections from KS by immunohistochemistry. LANA-1 and EphA2 were stained in consecutive sections of 15 AIDS-KS tissues of the skin (n = 14) and the lung (n = 1) (Fig. 4, a – f). In all KS tissues LANA-1 and EphA2 were expressed in the KS spindle cells (Fig. 4, a – f, black arrows). KS skin tissues showed increased numbers of KSHV positive cells (Fig. 4, a, c) and increased EphA2 staining was detected in the respective consecutive sections (Fig. 4, b, d). Numerous KSHV infected cells were also detected in lung KS (Fig. 4, e). In this tissue EphA2 staining resembled the distribution of LANA-1 positive cells, but was less homogeneously distributed as compared to the skin KS (Fig. 4, f). Breast carcinoma tissue was used as a positive control for EphA2 detection showing robust staining in the tumour cells (Fig. 4, g). Uninvolved skin tissues of the KS patients were negative for LANA-1 (Fig. 4, i) and stained only slightly positive for EphA2 in the epithelial cells of the epidermis (Fig. 4, h). In contrast, the epidermal cells of the skin overlaying KS tissue were strongly positive for EphA2 indicating an induction of EphA2 expression in the KS associated micromilieu. (fig. 4, b, d, green arrows)

Fig. 4. EphA2 is expressed in KSHV-infected spindle cells of Kaposi’s sarcoma.

(a – f) Immunohistochemical detection of LANA-1 and EphA2 in two different KS skin lesions (KS1, KS2) and one lung KS (KS3). (g) EphA2 expression in breast cancer was used as a positive control. (h, i) EphA2 and LNA-1 expression in uninvolved tissue sections of the skin of a KS patient. Similar tissue areas of consecutive sections are indicated by asterisks. Areas with KS spindle cells, exhibiting prominent nuclear LNA-1 staining and cytoplasmic EphA2 staining in consecutive sections are indicated by black arrows. Green arrows indicate EphA2 expression in the epidermis overlaying KS (b, d), in the tumour cells of breast cancer (g) or the epidermal layer of uninvolved skin (h), respectively. The magnification bar in panel e is 50 µm and is identical for all other panels.

Discussion

This study has shown that EphA2 directly interacts with glycoproteins H and L of KSHV. Moreover, interference with this interaction either by antibodies against EphA2, by soluble EphA2 ligands, by siRNA mediated knock-down of EphA2 or by competition with soluble EphA2 but not by closely related proteins unequivocally inhibited KSHV infection, whereas overexpression of EphA2 enhanced it. As far as KS and KS-derived cells are concerned, EphA2 expression and KSHV infection were strongly correlated both in cultured cells and KS tissues (Fig. 2g and 4, respectively). Knock-out of both EphA2 alleles essentially abrogated KSHV infection of murine endothelial cells (Fig. 2f). These findings identify EphA2 as a novel factor crucial for the infection of endothelial cells which are central to the pathogenesis of KS.

EphA2 is a member of a large family of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), the Ephrin receptors, comprising at least 14 members. The eight ephrins are their membrane-bound ligands. Although Ephrin receptors are widely expressed, they have not been implicated in herpesviral infections until today. The eight ephrins and their 15 receptors have important functions in cell division, angiogenesis, and cell migration. One ligand of this family, namely EphrinB2, has been identified as receptor for Nipah virus 37. However, EphrinB2 is not homologous to EphA2 on the amino acid level. Recently, EphA2 has been identified as a cellular co-factor for hepatitis C virus entry 38. In the case of HCV, the function for EphA2 is seen mostly in organizing other receptors on the cell surface in a fashion suitable for entry. A direct interaction of HCV virions or any viral protein with EphA2 has not been reported. Thus, the role for EphA2 in HCV infection is mechanistically different from our findings where EphA2 is a receptor for the viral glycoprotein complex gH/gL. Several lines of evidence show that EphA2 is a membrane receptor important for the infection especially of – but not limited to – cells of the endothelial lineage. First, EphA2 directly and specifically interacted with KSHV gH/gL, both when soluble (Fig. 1b, c) and membrane bound (Suppl. Fig. 1). It co-sedimented also with complete KSHV virions (Fig. 1d). Infection of adherent cells and cell lines was efficiently blocked by pre-incubation of the virus – but not the cells – with soluble EphA2 (Fig. 2e). Infection-inhibition was highly specific for EphA2 and not observed with the closely related EphA5 (Fig. 2d), which corresponds with the binding properties of KSHV gH/gL in immunoprecipitation (Suppl. table). However, engagement of the EphA2 receptor on the cells by soluble EphrinA4-Fc, a known inducer of EphA2 autophosphorylation, either 30 min before KSHV infection (Fig. 2d) or simultaneously in competition with KSHV did also reduce KSHV infection. Thus, activation of signal transduction from EphA2 is not sufficient to support KSHV infection. Direct interaction of EphA2 with the virion is required. Of course, phosphorylation of EphA2 by gH/gL (Fig. 3a – c) may still contribute to KSHV entry by membrane-organizing effects similar to those described for HCV 38. The data shown in figure 3d point into this direction. In summary, EphA2 is a receptor for KSHV mediating infection by binding the gH/gL protein complex on the virion envelope.

The role of gH/gL in herpesvirus entry is still poorly understood. At least in Herpes simplex virus, the gH/gL complex is usually thought to execute fusion after binding of other glycoproteins to the cellular receptor(s) 4 and KSHV gH/gL have also been shown to be required in fusion assays 22. EBV gH/gL has been implicated in fusion with epithelial cells after binding to several αV-integrins 39, 40. Further work will be required to determine more precisely the step(s) in the entry pathway dependent on KSHV gH/gL and EphA2. At least for heparan sulphate positive cells, EphA2 is not involved in attachment of KSHV to the cytoplasma membrane (data not shown). Following attachment, KSHV enters some cells by direct fusion with the cytoplasmic membrane 21. However, endocytosis has been reported to be the major pathway of entry for both fibroblasts and endothelial cells 19, 20. One of the best characterized effects of EphA2 ligand binding is receptor clustering and endocytosis 41, 42. Cross-linking of soluble gH/gL on both human and murine cells by an antibody resulted in efficient internalisation of the viral glycoproteins (Fig. 3d and Suppl. Fig. 7), comparable to that observed with the dimerized natural ligand EFNA1-Fc. Thus, KSHV mimics natural ligand-induced activation and might conceivably profit from this endocytotic stimulus. To date, integrins and focal adhesion kinase (FAK) have been implicated in KSHV entry via endocytosis 14, 17, 18, 43, 44. Interestingly, EphA2 is known to be physically and functionally associated with both integrins and FAK 45.

The relevance of several integrins in KSHV infection is a generally accepted notion reviewed in 5. Amongst others, two groups unequivocally identified integrin αVβ3 as a receptor for KSHV gB that is involved in the infection of monocytic 43 and fibroblastic 14 cells. In addition, soluble integrins αVβ3, αVβ5, or α3β1 inhibited KSHV infection of human microvascular endothelial cells, fibroblasts and kidney epithelium cells by approximately 30 to 60% 15, 17. When we used purified integrin α3β1, αVβ3 or a function blocking-antibody against this molecule under the same conditions that we used for soluble EphA2, inhibition was barely statistically significant (Fig. 2d). This does by no means negate the functional relevance for integrins in KSHV infection. Herpes viruses often use different receptors and entry pathways to infect different cell types. Whereas soluble integrins or antibodies against integrins have been found to block KSHV infection of monocytes, epithelial cells and human microvascular endothelial cells 15, 43, the data shown in figure 2d were obtained using a cell line derived from lymphatic endothelium. We are not aware of other work examining the role of integrins in the KSHV infection of cells derived from lymphatic endothelium or KS.

Silencing of EphA2 expression by RNA-interference reduced infection of primary lymphatic endothelial cells by up to 80% (Fig. 2c). As RNA-interference rarely is able to fully abrogate expression of a target gene, this dramatic drop emphasises that the interaction of gH/gL with EphA2 can be seen as crucial for the infection of LEC. This is underlined by the almost complete abrogation of KSHV susceptibility through EphA2 knockout in murine pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells and the close correlation between EphA2 infection and KSHV permissiveness of human cells derived from lymphatic endothelium (Fig. 2g). KS is thought to be derived from lymphatic endothelial cells. We show here that EphA2 is highly expressed in KS tissue sections, but only few cells of uninvolved skin from the same patients stained positive for EphA2. Notably, the areas highly positive for EphA2 clearly overlapped with areas of KSHV infection.

EphA2 is overexpressed in numerous malignancies (reviewed in 26) and deregulated EphA2 signalling is a feature of many solid tumours. EphA2 expression is also associated with tumour progression 46. Currently, data on the functional consequences of EphA2 phosphorylation for oncogenesis are controversial. On the one hand, activation of EphA2 by ligand binding may result in endocytosis, degradation, and thus diminished activity of EphA2 41. On the other hand, EphA2 phosphorylation and kinase activity have been shown to promote tumour growth and metastasis 47. Thus, the functional role of EphA2 activation in solid tumours in general remains to be elucidated. However, the role of EphA2 in KS is far clearer. EphA2 is known to be expressed and phosphorylated in KS tissues 29, and EphA2 stimulation enhances endothelial cell migration and angiogenesis 25. Neo-vascularisation is a hallmark of KS, and many studies point at a pivotal role of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in KS pathogenesis 48. However, neoangiogenesis via VEGF and its receptor also depends on activation of EphA2, which is thus a key player in angiogenesis 25, 29. VEGF-induced angiogenesis and tumour progression could be blocked efficiently with soluble EphA2-Fc both in vitro and in vivo24, 25 and soluble EphA2 is therefore under investigation as an anti-tumour agent 49.

Our study now identifies soluble EphA2 as a potent antiviral agent that inhibits KSHV infection. Both lytic KSHV replication and latency contribute to KS pathogenesis. Chronic, ongoing KSHV infection and neo-vascularisation are the key features of KS. EphA2 plays a crucial role in both of these processes. Synergies between inhibiting viral entry and blocking angiogenesis with soluble EphA2 or antibodies against EphA2 are likely. In summary, our results identify EphA2 as KSHV receptor and possible new target to combat KS, as EphA2 is highly expressed in KS tissues, plays a critical role in KSHV infection of endothelial cells and is known to be involved in angiogenesis.

Methods

Cells, virus, plasmids, transfection, and recombinant protein production

Adherent cell lines were cultivated in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and Gentamycin at 37°C, 7% CO2, at 80% humidity. Human LEC and murine 28 endothelial cells were cultivated in EGM-2 MV (Lonza). Lung microvascular endothelial cells were isolated from wild-type and EphA2 knockout mice as described before 28. Transduction with LZRS retrovirus expressing wild-type EphA2 has been described earlier 28. Human LEC were purchased from Lonza. HUVEC were purchased from Promocell and maintained in ECGM (Promocell). KSImm cells were kindly provided by Adriana Albini, SLK 33 cells were obtained from the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent program. KS cells M7/2 have been described before 31. rKSHV.219 30 virus preparation and infection assays were carried out essentially as described previously 50. Tangential flow filtration (TFF) followed by diafiltration against PBS was used as the first step to concentrate and purify KSHV virions from the supernatant of lytically induced cells modified from 51. Briefly, the minimate system (PALL Life Sciences) and TFF capsules with a cutoff of 300 kDa were used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A transmembrane pressure of 1 bar was used at a flow rate of 80 ml/min. Further virus purification was performed by centrifugation on Opti-Prep (iodixanol) gradients 14. For KSHV infections at low titer, supernatant from KSHV.219 producing 293 cells was concentrated by centrifugation as previously described 9. HVS-M45 was generated by recombination of five overlapping cosmids 52. Here, the HVS oncogenes stpC and tip were deleted by digestion of cosmid331EGFP 53 with Bst1107I, followed by religation, yielding cosmid331EGFP-deltaStpC/Tip. Blocking of infection with soluble receptor was assayed by a 30 min pre-incubation of the virus dilution at room temperature with the indicated concentrations of the solEphA2-Fc or Fc and subsequent infection. Recombinant Fc-fusion proteins were prepared as described previously 6. Strep-tagged proteins were purified under native conditions by Streptactin chromatography and elution with 3 mM biotin in PBS. solEphA2-Fc comprises amino acids 25 to 534 of human EphA2 in the pAB61 Fc-fusion backbone vector. EFNA1-Fc comprises amino acids 19 to 188 of human EphrinA1 (EFNA1) in the pAB61 Fc-fusion backbone vector. Expression plasmids pEphA2mychis (full length, ref|NP_004422.2|), pEphA2ΔICmychis (aa 1–560), and pmuEphA2ΔICmychis (aa 1–560) were generated by PCR amplification of the respective fragments from EphA2 cDNA. The resulting amplicons were inserted into the pcDNA4a backbone. An antiserum against EphA2 was raised in rabbits using recombinant soluble EphA2. Whole antibodies were purified from this serum using protein A sepharose.

Transfection was carried out as described previously 9. Stably transfected cell populations were generated by selection with 100 µg/ml Zeocin (Invitrogen). Integrin α3β1 (cat. no. CC1029), αVβ3 (cat. no. CC1020), anti EphA2 monoclonal antibody D7 (cat. no. 05-480) and anti-integrin αVβ3 clone LM609 (cat. no. MAB1976) were purchased from Chemicon/Millipore. Recombinant human EphA2, EphA5 and EphrinA4-Fc were purchased from R&D, recombinant EphA4 was purchased from Biomol.

Surface biotinylation, immunoprecipitation, and mass spectrometry

Biotinylation of cellular membrane proteins was performed with EZ-link Sulfo-NHS-Biotin (Pierce) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For immunoprecipitation, cells were lysed in 1% NP40 150 mM NaCl 2.5 mM EDTA/EGTA 20 mM HEPES pH 7.4. The lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 20000 × g and supernatants were immunoprecipitated with Fc-fusion proteins coupled to Protein-A-sepharose (GE Healthcare). Coupling of proteins was achieved by pre-adsorbing 1 ml of protein containing supernatant per sample to the Protein-A-sepharose beads. For mass spectrometry analysis, 3 densely confluent 10 cm culture dishes of sog9 mouse fibroblasts were used per immunoprecipitation sample. For small–scale immunoprecipitation, approximately two million transfected 293T cells were lysed. Samples were washed three times with lysis buffer, separated on 8–16% PAA gradient gels (Invitrogen), and stained with colloidal Coomassie blue or subjected to Western blot analysis. Bands were excised from the gel and prepared for mass spectrometric identification as described earlier 54. Briefly, the protein was digested in the gel using trypsin. The peptides were extracted and desalted for MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry MALDImicro MX; Waters Corp.). In addition, the extract was applied to nanoLC-MS/MS using UPLC and Q-TOF Premier (Waters Corp.). Both methods independently identified Ephrin type A receptor 2 (supplementary table).

FACS binding assays

Protein-containing supernatants from transfected 293T cells were assayed by Western blot for comparable protein expression levels. Further purification was omitted in order not to damage the non-covalent gH/gL interaction. These supernatants were buffered by addition of HEPES at a final concentration of 25 mM and used for binding studies which were carried out as described previously 9. Cells were incubated with the protein-containing supernatants for 1 h, washed, and then incubated with anti-human-Fc-FITC (Dako) for 1 h, washed again, and analysed on a Becton-Dickinson FACSCalibur. All steps were performed at 4°C or on ice. For competition of gHΔTM-FcStrep/gL binding to cell surfaces by soluble receptor, gHΔTM-FcStrep/gL containing supernatants were pre-incubated for 30 min at room temperature with solEphA2-Fc or Fc at the indicated concentrations. The binding assays themselves were carried out as described above except that Streptactin-PE (IBA) was used for secondary detection.

siRNA transfection

LEC cells were seeded in 12 well plates and transfected at app. 70% confluency with siRNA pools from Dharmacon either targeting EphA2 (siGENOME SMARTpool siRNA D-003116-06), EphB4 (siGENOME SMARTpool M-003124-02-0005) or non-targeting siRNA pool (siGENOME Non-Targeting siRNA Pool #2 D-001206-14-05). For one well, 50 nmol of each pool were diluted in 25 µl H2O and 25 µl Optimem (Gibco). 1 µl Dharmafect-1 (Dharmacon) pre-diluted in 50 µl Optimem was added followed by mixing and 5 min of incubation. 400 µl of EGM-2 MV growth medium was added and the whole mixture was applied to the cells. Medium was exchanged after 24 h.

RNA extraction and quantitative reverse-transcription PCR

Total cellular RNA was extracted from cultured cells using the Nucleospin RNA III kit (Machery&Nagel) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Simultaneous quantitative reverse-transcription PCR for KSHV LANA-1 and GAPDH transcripts was performed using Quantitect Multiplex RT-PCR kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Oligonucleotides qRT-LANA-Fw (5`-TCC GGC TGA CTT ATA AAC AAC CAG ATT TC-3`), qRTLANA-Rev (5`-TCC CGA CCT CAG GCG CA-3`), qRT-GAPDH-Fw (5`-GCC TCA AGA TCA TCA GCA ATG CC-3`), qRT-GAPDH-Rev (5`-CCA CGA TCA CAA AGT TGT CAT GGA-3`) and labelled probes for LANA-1 (5`-FAM-CGA GGA TGG CGC CCC CGG GA –BHQ-1-3`) and GAPDH (5`-Yakima-Yellow-CCT GCA CCA CCA ACT GCT TAG CAC C –BHQ-1-3`) for the simultaneous detection of LANA-1 and GAPDH transcripts. PCR efficiency was determined and used to calculate relative transcript levels using the delta-delta Ct method. Quantitation of EphA2 and actin transcripts was done with a two-step RT-PCR and SYBR-green labelling as described before (oligonucleotides: EphA2-RT-1830-Fw: 5`-ATC CTG TGT CAC TCG GCA GAA G-3`; EphA2-RT-2038-Rev: 5`-CCT CTA GGC GGA TGA TGT TGT G-3`; Aktin-Fw: 5`-CCA TCT ACG AGG GGT ATG-3`; Aktin-Rev: 5`-CGT GGC CAT CTC TTG CTC-3`)55. Absolute quantitation was done using a standard curve obtained from diluted plasmid DNA.

Detection of EphA2 phosphorylation

EphA2 phosphorylation in 293T cells was measured with ‘DuoSet® IC Human Phospho-EphA2’ ELISA (R&D Systems). Stimulation was achieved by inoculating the cells for 10 min with rKSHV.219 or an identically prepared control preparation from the supernatant of chemically induced KSHV-negative 293 cells. Alternatively, 293T cells were stimulated with purified proteins and lysed in 1% NP40 150 mM NaCl 2.5 mM EDTA/EGTA 20 mM HEPES pH 7.4 with addition of 5 mM sodium orthovanadate and 1 mM PMSF. EphA2 was precipitated with protein A sepharose preadsorbed with 50µl of anti-EphA2 rabbit serum, followed by western blotting against phospho-tyrosine (4G10 mouse hybridoma supernatant) and EphA2 (Sigma, anti-EphA2 6F8 from mouse).

Immunofluorescence and endocytosis assay

gHΔTM-FcStrep/gL, EFNA1-Fc or Fc proteins were pre-incubated for 30 min at room temperature with the indicated antihuman-Fc secondary antibodies (1:100) for cross-linking. The proteins were then incubated with cells on coverslips for 1h at 4° C. After a brief wash the cells were shifted to 37° C and subjected to immunofluorescence analysis at the indicated time points. The cells were briefly rinsed with PBS three times and fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde in PBS, followed by quenching with 0.1 M glycine and permeabilisation with 0.1% NP40 in PBS for 5 min. After blocking with 2% BSA and 5% FBS in PBS, the cells were incubated with the respective antibodies where indicated for 1 h at room temperature and mounted with ProLong Gold mounting medium (Invitrogen). Images were acquired on a Leica TCS SP5 confocal laser scanning microscope in sequential scanning mode to eliminate crosstalk.

Immunohistochemistry

KS tissues were obtained from 15 HIV-1 infected patients (skin KS, n = 14; lung KS, n = 1). Stainings of paraformaldehyde-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections for EphA2 and LNA-1 were performed as previously described 56. A rabbit anti-human EphA2 polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz, sc-924, diluted 1:100) and a rat anti-LNA-1 monoclonal antibody (Tebu-bio, cat. no. 13-210-100, diluted 1:250) were used as primary antibodies. Primary antibody binding was detected using the respective Vectastain Elite ABC Kits (Vector Laboratories). For both antibodies the citrate buffer pH 6.0 (DakoCytomation) was used for the antigen retrieval. The sections were then developed using NovaRed Substrate (Vector Laboratories) and counterstained with Hematoxylin Gill III (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). Stained cells were photographed using an Aristoplan microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) equipped with a 10× and 25× objective and a 3CCD Exwave HAD color camera (Sony, Berlin, Germany). Control staining was performed without primary antibody and yielded negative results (data not shown).

Statistical analysis

All results are expressed as arithmetic means. Error bars represent either +/− s.e.m or s.d. Data were analyzed with unpaired two-tailed t tests (SPSS 16, GraphPad Prism 5).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Akademie der Wissenschaften und der Literatur (Mainz), the European Community research project TargetHerpes, Deutsche Forschungsgemein-schaft, SFB 643 and graduate school 1071 “viruses of the immune system”. M. Stürzl and E. N. were sponsored by a grants from the interdisciplinary center for clinical research (IZKF) of the University of Erlangen and the German Cancer Aid. We thank Laura Wall for experimental assistance an Ronald C. Desrosiers for helpful discussions and critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary information is available on the Nature Medicine website.

Author contributions

A. Hahn and F. N designed the study. A. Hahn, J. K., E. W. performed the key experiments. J. I., K. S., M. Schmidt. and A. Holzer. performed real-time PCR experiments, cell culture and infection assays. S. K. performed mass spectrometry and analysed the data. J. C., A. E., J. M., D. G. and N. H. B. contributed key reagents. E. N. and M. Stürzl helped with endothelial cell cultures and performed immunohistochemistry experiments. A. Hahn and F. N. wrote the manuscript. B. F. contributed expertise and helped to write the paper.

Competing financial interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Chang Y, et al. Identification of herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in AIDS-associated Kaposi's sarcoma. Science. 1994;266:1865–1869. doi: 10.1126/science.7997879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cesarman E, Chang Y, Moore PS, Said JW, Knowles DM. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in AIDS-related body-cavity-based lymphomas. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995;332:1186–1191. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199505043321802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soulier J, et al. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in multicentric Castleman's disease. Blood. 1995;86:1276–1280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campadelli-Fiume G, et al. The multipartite system that mediates entry of herpes simplex virus into the cell. Rev. Med. Virol. 2007 doi: 10.1002/rmv.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chandran B. Early Events in Kaposi's Sarcoma-Associated Herpesvirus Infection of Target Cells. J. Virol. 2010;84:2188–2199. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01334-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Birkmann A, et al. Cell Surface Heparan Sulfate Is a Receptor for Human Herpesvirus 8 and Interacts with Envelope Glycoprotein K8.1. J Virol. 2001;75:11583–11593. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.23.11583-11593.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang FZ, Akula SM, Pramod NP, Zeng L, Chandran B. Human herpesvirus 8 envelope glycoprotein K8.1A interaction with the target cells involves heparan sulfate. J Virol. 2001;75:7517–7527. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.16.7517-7527.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akula SM, Pramod NP, Wang FZ, Chandran B. Human herpesvirus 8 envelope-associated glycoprotein B interacts with heparan sulfate-like moieties. Virology. 2001;284:235–249. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.0921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hahn A, et al. Kaposi's Sarcoma-Associated Herpesvirus gH/gL: Glycoprotein Export and Interaction with Cellular Receptors. J. Virol. 2009;83:396–407. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01170-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mark L, Lee WH, Spiller OB, Villoutreix BO, Blom AM. The Ka-posi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus complement control protein (KCP) binds to heparin and cell surfaces via positively charged amino acids in CCP1-2. Mol. Immunol. 2006;43:1665–1675. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2005.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jarousse N, Chandran B, Coscoy L. Lack of heparan sulfate expression in B-cell lines: implications for Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus and murine gammaherpesvirus 68 infections. J. Virol. 2008;82:12591–12597. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01167-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rappocciolo G, et al. DC-SIGN Is a Receptor for Human Herpesvirus 8 on Dendritic Cells and Macrophages. J Immunol. 2006;176:1741–1749. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.3.1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rappocciolo G, et al. Human Herpesvirus 8 Infects and Replicates in Primary Cultures of Activated B Lymphocytes through DC-SIGN. J. Virol. 2008;82:4793–4806. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01587-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garrigues HJ, Rubinchikova YE, DiPersio CM, Rose TM. Integrin {alpha}V 3 Binds to the RGD Motif of Glycoprotein B of Kaposi's Sarcoma-Associated Herpesvirus and Functions as an RGD-Dependent Entry Receptor. J. Virol. 2008;82:1570–1580. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01673-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Veettil MV, et al. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus forms a mul-timolecular complex of integrins (alphaVbeta5, alphaVbeta3, and alpha3beta1) and CD98-xCT during infection of human dermal microvascular endothelial cells, and CD98-xCT is essential for the postentry stage of infection. J. Virol. 2008;82:12126–12144. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01146-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Naranatt PP, Akula SM, Zien CA, Krishnan HH, Chandran B. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus induces the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-PKC-zeta-MEK-ERK signaling pathway in target cells early during infection: implications for infectivity. J. Virol. 2003;77:1524–1539. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.2.1524-1539.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Akula SM, Pramod NP, Wang FZ, Chandran B. Integrin alpha3beta1 (CD 49c/29) is a cellular receptor for Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV/HHV-8) entry into the target cells. Cell. 2002;108:407–419. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00628-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharma-Walia N, Naranatt PP, Krishnan HH, Zeng L, Chandran B. Kaposi's Sarcoma-Associated Herpesvirus/Human Herpesvirus 8 Envelope Glycoprotein gB Induces the Integrin-Dependent Focal Adhesion Kinase-Src-Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase-Rho GTPase Signal Pathways and Cytoskeletal Rearrangements. J. Virol. 2004;78:4207–4223. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.8.4207-4223.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raghu H, Sharma-Walia N, Veettil MV, Sadagopan S, Chandran B. Kaposi's Sarcoma-Associated Herpesvirus Utilizes an Actin Polymerization-Dependent Macropinocytic Pathway To Enter Human Dermal Microvascular Endothelial and Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells. J. Virol. 2009;83:4895–4911. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02498-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Akula SM, et al. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (human herpesvirus 8) infection of human fibroblast cells occurs through endocytosis. J. Virol. 2003;77:7978–7990. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.14.7978-7990.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaleeba JAR, Berger EA. Kaposi's Sarcoma-Associated Herpesvirus Fusion-Entry Receptor: Cystine Transporter xCT. Science. 2006;311:1921–1924. doi: 10.1126/science.1120878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pertel PE. Human Herpesvirus 8 Glycoprotein B (gB), gH, and gL Can Mediate Cell Fusion. J. Virol. 2002;76:4390–4400. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.9.4390-4400.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walker-Daniels J, Hess AR, Hendrix MJC, Kinch MS. Differential Regulation of EphA2 in Normal and Malignant Cells. Am J Pathol. 2003;162:1037–1042. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63899-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brantley DM, et al. Soluble Eph A receptors inhibit tumor angiogenesis and progression in vivo. Oncogene. 2002;21:7011–7026. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheng N, et al. Blockade of EphA receptor tyrosine kinase activation inhibits vascular endothelial cell growth factor-induced angiogenesis. Mol. Cancer Res. 2002;1:2–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wykosky J, Debinski W. The EphA2 Receptor and EphrinA1 Ligand in Solid Tumors: Function and Therapeutic Targeting. Mol Cancer Res. 2008;6:1795–1806. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Banfield BW, Leduc Y, Esford L, Schubert K, Tufaro F. Sequential isolation of proteoglycan synthesis mutants by using herpes simplex virus as a selective agent: evidence for a proteoglycan-independent virus entry pathway. J. Virol. 1995;69:3290–3298. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.6.3290-3298.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brantley-Sieders DM, et al. EphA2 receptor tyrosine kinase regulates endothelial cell migration and vascular assembly through phosphoinositide 3-kinase-mediated Rac1 GTPase activation. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:2037–2049. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ogawa K, et al. The ephrin-A1 ligand and its receptor, EphA2, are expressed during tumor neovascularization. Oncogene. 2000;19:6043–6052. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vieira J, O'Hearn PM. Use of the red fluorescent protein as a marker of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus lytic gene expression. Virology. 2004;325:225–240. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stürzl M, et al. Identification of interleukin-1 and platelet-derived growth factor-B as major mitogens for the spindle cells of Kaposi's sarcoma: a combined in vitro and in vivo analysis. Oncogene. 1995;10:2007–2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Albini A, et al. The beta-core fragment of human chorionic gonadotrophin inhibits growth of Kaposi's sarcoma-derived cells and a new immortalized Kaposi's sarcoma cell line. AIDS. 1997;11:713–721. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199706000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Herndier BG, et al. Characterization of a human Kaposi's sarcoma cell line that induces angiogenic tumors in animals. AIDS. 1994;8 doi: 10.1097/00002030-199405000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bechtel JT, Liang Y, Hvidding J, Ganem D. Host range of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus in cultured cells. J. Virol. 2003;77:6474–6481. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.11.6474-6481.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaleeba JAR, Berger EA. Broad target cell selectivity of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus glycoprotein-mediated cell fusion and virion entry. Virology. 2006;354:7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kullander K, Klein R. Mechanisms and functions of eph and ephrin signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:475–486. doi: 10.1038/nrm856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Negrete OA, et al. EphrinB2 is the entry receptor for Nipah virus, an emergent deadly paramyxovirus. Nature. 2005;436:401–405. doi: 10.1038/nature03838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lupberger J, et al. EGFR and EphA2 are host factors for hepatitis C virus entry and possible targets for antiviral therapy. Nat. Med. 2011;17:589–595. doi: 10.1038/nm.2341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chesnokova LS, Nishimura SL, Hutt-Fletcher LM. Fusion of epithelial cells by Epstein-Barr virus proteins is triggered by binding of viral glycoproteins gHgL to integrins alphavbeta6 or alphavbeta8. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:20464–20469. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907508106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chesnokova LS, Hutt-Fletcher LM. Fusion of EBV with epithelial cells can be triggered by {alpha}v{beta}5 in addition to {alpha}v{beta}6 and {alpha}v{beta}8 and integrin binding triggers a conformational change in gHgL. J. Virol. 2011 doi: 10.1128/JVI.05580-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walker-Daniels J, Riese DJ, Kinch MS. c-Cbl-dependent EphA2 pro-tein degradation is induced by ligand binding. Mol. Cancer Res. 2002;1:79–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhuang G, Hunter S, Hwang Y, Chen J. Regulation of EphA2 Receptor Endocytosis by SHIP2 Lipid Phosphatase via Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinasedependent Rac1 Activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:2683–2694. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608509200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kerur N, et al. Characterization of entry and infection of monocytic THP-1 cells by Kaposi's sarcoma associated herpesvirus (KSHV): Role of heparan sulfate, DC-SIGN, integrins and signaling. Virology. 2010;406:103–116. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Krishnan HH, Sharma-Walia N, Streblow DN, Naranatt PP, Chandran B. Focal Adhesion Kinase Is Critical for Entry of Kaposi's Sarcoma-Associated Herpesvirus into Target Cells. J. Virol. 2006;80:1167–1180. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.3.1167-1180.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Parri M, et al. EphrinA1 Activates a Src/Focal Adhesion Kinase-mediated Motility Response Leading to Rho-dependent Actino/Myosin Contractility. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:19619–19628. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701319200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thaker PH, et al. EphA2 expression is associated with aggressive features in ovarian carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2004;10:5145–5150. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fang WB, Brantley-Sieders DM, Parker MA, Reith AD, Chen J. A kinase-dependent role for EphA2 receptor in promoting tumor growth and metastasis. Oncogene. 2005;24:7859–7868. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang BT, et al. Transgenic expression of the chemokine receptor encoded by human herpesvirus 8 induces an angioproliferative disease resembling Kaposi's sarcoma. J. Exp. Med. 2000;191:445–454. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.3.445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dobrzanski P, et al. Antiangiogenic and antitumor efficacy of EphA2 receptor antagonist. Cancer Res. 2004;64:910–919. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-3430-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Myoung J, Ganem D. Generation of a doxycycline-inducible KSHV producer cell line of endothelial origin: Maintenance of tight latency with efficient reactivation upon induction. Journal of Virological Methods. 2011;174:12–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2011.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wickramasinghe SR, Kalbfuss B, Zimmermann A, Thom V, Reichl U. Tangential flow microfiltration and ultrafiltration for human influenza A virus concentration and purification. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2005;92:199–208. doi: 10.1002/bit.20599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ensser A, Pfinder A, Muller-Fleckenstein I, Fleckenstein B. The URNA genes of herpesvirus saimiri (strain C488) are dispensable for transformation of human T cells in vitro. J. Virol. 1999;73:10551–10555. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.12.10551-10555.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Glykofrydes D, et al. Herpesvirus saimiri vFLIP provides an antiapoptotic function but is not essential for viral replication, transformation, or pathogenicity. J. Virol. 2000;74:11919–11927. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.24.11919-11927.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.König S, et al. Sodium dodecyl sulfate versus acid-labile surfactant gel electrophoresis: comparative proteomic studies on rat retina and mouse brain. Electrophoresis. 2003;24:751–756. doi: 10.1002/elps.200390090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schmidt K, Wies E, Neipel F. Kaposi's Sarcoma-Associated Herpesvirus Viral Interferon Regulatory Factor 3 Inhibits Gamma Interferon and Major Histocompatibility Complex Class II Expression. J. Virol. 2011;85:4530–4537. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02123-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Naschberger E, et al. Angiostatic immune reaction in colorectal carcinoma: Impact on survival and perspectives for antiangiogenic therapy. Int. J. Cancer. 2008;123:2120–2129. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.