Abstract

BACKGROUND

The development of water-soluble nanodevices extends the potential use of compounds developed for other purposes (e.g. antifungal drugs or antibiotics) for applications in agriculture. For example, the broad-spectrum, water-insoluble, macrolide polyene antibiotic amphotericin B(AMB) could be used to inhibit phytopathogenic fungi. A new formulation embedding AMB in nanodisks (NDs) enhances antibiotic solubility and confers protection against environmental damage. In the present study, AMB-NDs were tested for efficacy against several phytopathogenic fungi in vitro and on infected living plants (chickpea and wheat).

RESULTS

Compared with AMB in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO), AMB-NDs increased the sensitivity of several fungal species to this antimycotic in vitro. Sensitivity varied with fungal species as well as with the forma specialis. Phytophthora cinnamomi, previously reported as insensitive to other polyene antimycotics, remained unaffected at the doses examined. Some effect against disease symptoms were obtained with AMB-NDs against fusarium wilt in chickpea, whereas the results were highly variable in wheat, depending on both the species and treatment regimen.

CONCLUSION

The results confirm that formulation of AMB into ND increases its effectiveness against phytopathogenic fungi in vitro, opening the possibility for its use on infected plants in the field.

Keywords: nanodisks, amphotericin B, drug delivery, plant fungal diseases, chickpea, wheat

1 INTRODUCTION

Developing nanodevices for agricultural or plant research applications has become a highly topical subject in recent years.1 The agrochemical world is being revolutionised by nanotechnology in a way similar to that of pharmacology. Nanoencapsulation can improve solubility, application ease and enhance penetration through cuticles and tissues, allowing slow and constant release of active substances.2–4 These properties permit the use of lower doses of active compounds, creating less ecotoxicity and better management.5 In addition, chemicals used to date for other purposes (e.g. antifungal drugs or antibiotics) could be adapted to applications in the field.6

Amphotericin B (AMB) is an antifungal drug with a mechanism of action that involves interaction with membrane sterols, such as ergosterol. The interaction results in membrane pore formation, ion leakage and, ultimately, cell death.7,8 AMB belongs to the family of macrolide polyene antimycotics, produced by Streptomyces spp. and widely used for treatment of opportunistic fungal infections (for example, those caused by Aspergillus, Fusarium or Candida).9 Additionally, other compounds from the same family, such as pimaricin/natamycin, are used in the food industry in order to prevent fungal contamination.10,11 However, members of this family of compunds have inherent low solubility in aqueous media and a highsusceptibilitytooxidationandlight-induceddamage,thereby affecting their biological activity and functional utility.12 Recently, a new formulation of AMB was reported in which phospholipid, apolipoprotein A-I (apoA-I) and AMB were combined to form non-covalent ternary assemblies referred to as nanodisks (NDs). This formulation significantly increased AMB solubility and conferred protection against ultra violet light and oxidation-induced damage.6,13

In the present work, the effectiveness of AMB-NDs for the treatment of fungal diseases affecting crops was examined. Several fungi were exposed in vitro to different concentrations of AMB-NDs, free AMB or empty NDs, and the effective dose required to inhibit fungal growth by 50% (ED50) was determined. Furthermore, the effect of AMB-NDs on plants inoculated with aerial or systemic fungi was evaluated using wheat (Triticum aestivum, T. turgidum var. durum) and chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.).

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Fungal species and plant material

The following fungal species were used for in vitro experiments in petri dishes:

Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. melonis, attacking muskmelon (Cucumis melo) (from the Spanish Type Culture Collection, reference CECT 20474);

F.oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici, attacking tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) (from the Spanish Type Culture Collection, reference CECT 2866);

Phytophthora cinnamomi, attacking avocado (Persea americana) (from the Spanish Type Culture Collection, reference CECT 20186);

Verticillium dahliae, attacking muskmelon (C. melo) (from the Spanish Type Culture Collection, reference CECT 2884);

V. albo-atrum, attacking tomato (L. esculentum) (from the Spanish Type Culture Collection, reference CECT 2693);

Colletotrichum acutatum, attacking strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa) (from the Spanish Type Culture Collection, reference CECT 20411);

F.oxysporum f. sp. ciceris race 5, attacking chickpea (C.arietinum) (kindly provided by Dr Chen, Washington State University, Pullman, WA);

Botritis fabae, attacking faba bean (Vicia faba) (from the IFAPA Alameda del Obispo collection);

Ascochyta fabae, attacking faba bean (V. faba) (from the IFAPA Alameda del Obispo collection).

In addition, Puccinia triticina (wheat leaf rust) attacking wheat (from the IFAPA Alameda del Obispo collection) and F. oxysporum f. sp. ciceris were used for in planta experiments.

Commercial cultivars of bread and durum wheat (T.aestivum var. ‘Califa Sur’ and T.turgidum var. durum var. ‘Meridiano’ respectively) and chickpea (C. arietinum genotype JG62) were used for pot experiments in growth chambers.

2.2 AMB-ND preparation

Recombinant apoA-I was produced as previously described.14 Amphotericin B lipid complex (ABLC) and AMB deoxycholate were obtained from the In-patient Pharmacy at the Children's Hospital and Research Center, Oakland. AMB deoxycholate was reconstituted in sterile deionised water according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Unless otherwise indicated, AMB-NDs were prepared as described by Tufteland et al.15 Briefly, ABLC was gently agitated to disperse the settled mixture. Quantities of 1 mL of ABLC suspension (5 mg of phospholipid, 5 mg of AMB) and 0.4 mL of apoA-I (5 mg mL–1) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 20 mM of sodium phosphate, pH 7.4, 150 mM of sodium chloride) were combined, and the vessel was flushed with nitrogen gas, capped and subjected to bath sonication at 22 °C for 40 min. The resulting solution was sterile filtered (0.22 μm) and stored at 4 °C until use. Empty NDs lacking AMB were prepared according to Oda et al.13

2.3 Fungal in vitro studies

AMB-ND fungal growth inhibition assays were conducted using a solid agar medium, specifically potato dextrose agar (PDA), except for A. fabae, in which case V8 medium was used. AMB-NDs, free AMB [in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) as solubilisation vehicle] or empty NDs from stock solutions were added to the medium to obtain final concentrations of 0.1, 0.5, 1.0 and 2.0 μg mL–1. Negative controls adding sterile distilled water were included. The amended medium was poured in petri dishes (90 mm diameter) and after solidification was inoculated with a 5 mm diameter mycelial disc cut from the edge of an actively growing culture of the tested fungi. Radial growth of the mycelium was measured after 8 days of incubation at 24 °C in darkness (under a 12 h light photoperiod for A. fabae).

2.4 Inoculated plant studies

2.4.1 F. oxysporum in chickpea

Growth and inoculation of chickpea plants with F. oxysporum f. sp. ciceris were performed according to Iruela et al.16 Colonised filter paper cultures of F. oxysporum race 5 were cultured in potato dextrose broth (PDB) (24 g L–1) at 25 °C with light for 1 week to produce liquid cultures of the pathogen. The liquid cultures were filtered through cheesecloth to remove mycelia. The spore suspension was then pelleted by centrifugation at low speed (3000 rpm) for 3 min. After the supernatant was discarded, conidia were diluted with sterile water to obtain a concentration of 106 spores mL–1. Chickpea seedlings at the 3–4-node stages (23 days old) were inoculated as described by Tullu et al.17 Inoculated plants were grown in perlite in a growth room with a temperature regime of 25 and 22 °C (12 : 12 h day : night photoperiod). The plants were watered daily and supplied with nutrient solution once a week after inoculation.

Four different treatments were applied on the plants:

preventive foliar treatment;

curative foliar treatment;

preventive irrigation treatment;

curative irrigation treatment.

Preventive treatments were applied once, 24 h before inoculation with the fungus, and curative treatments were applied once, 24 h after fungal inoculation. Foliar treatments consisted of spray application (20 mL per plant) to plant leaves, and irrigation treatments consisted of application of solution (30 mL per plant) through the soil. Three different concentrations of AMB-NDs were used: 0.1, 1.0 and 10.0 mg L–1.

A qualitative scale was used to evaluate fusarium wilt incidence, depicting healthy plants (no symptoms), plants showing wilt symptoms (symptoms) and dead plants (dead). Data were collected 15, 18, 19 and 21 days after inoculation (DAI).

2.4.2 P. triticina in wheat

Plants were grown in 200 mL plastic pots filled with a 1 : 1 mixture of sand and peat. Twenty-day-old seedlings were inoculated by dusting freshly collected wheat leaf rust spores (2 mg of spores per plant) diluted in pure talc (1 : 10) of the P. triticina isolate, using a spore-settling tower.18 Inoculated plants were incubated for 24 h in an incubation chamber at 20 °C in complete darkness at 100% relative humidity, and then transferred to a growth chamber at 20 °C with a 14 : 10 h day : night photoperiod.

The treatments and concentrations were the same as those described above for F. oxysporum in chickpea.

Disease severity (DS) was assessed by visual estimation of the leaf area covered with rust pustules, indicating the percentage of leaf area affected by the fungus (ranging from 0 to 100%). Data were collected 7 and 12 DAI.

2.5 Statistical analysis

For the fungal in vitro assays, every treatment and concentration for each of the nine isolates were replicated 3 times. The entire experiment was conducted using a randomised experimental design. ED50 was calculated using probit analysis. For the pot experiments with inoculated plants, seven replicates per treatment and concentration were used in a randomised design. ANOVA was calculated using Statistix 8.0 for Windows.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Fungal sensitivity to AMB-NDs

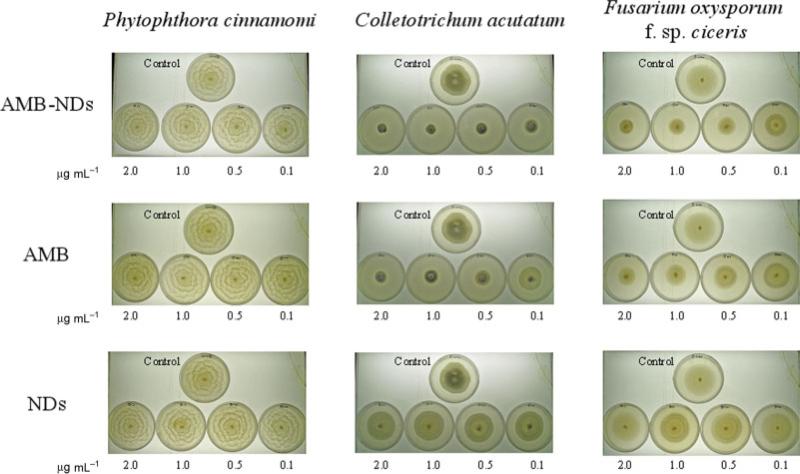

There was great variation in the response to different concentrations of AMB-NDs and AMB in DMSO, depending on the fungal species (Table 1, Fig. 1). Nearly half of the tested fungal species were highly sensitive to treatment with AMB-NDs, showing an ED50 lower than 0.1 μg mL–1 (V. dahliae, V. albo-atrum, C. acutatum and B. fabae). Two more species (F. oxysporum f. sp. ciceris and A. fabae) showed good sensitivity, with an ED50 lower than 1.5 μg mL–1. The other two isolates of F. oxysporum (f. sp. melonis and f. sp. lycopersici) showed reduced sensitivity to the antifungal, with ED50 values above the tested concentration (17.8 and 6.3 μg mL–1 respectively). P. cinnamomi was unaffected by any formulation of AMB.

Table 1.

Sensitivity of several fungal plant pathogens to different concentrations of AMB-NDs, AMB and empty NDs. ED50 is the effective dose reducing the fungal growth by 50 (± SE)

| Diameter of the colony (mm)a |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | Concentration (μg mL–1) | Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. melonis | F. oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici | Phytophthora cinnamomi | Verticillium dahliae | V. albo-atrum | Colletotrichum acutatum | F. oxysporum f. sp. ciceris | Ascochyta fabae | Botritis fabae |

| Control | 0.0 | 73 a | 74 a | 81 a | 34 a | 24 b | 57 a | 62 ab | 37 abc | 75 a |

| AMB-NDs | 2.0 | 53 e | 47 f | 80 a | 11 f | 5 d | 19 e | 29 g | 17 g | 5 e |

| 1.0 | 53 e | 50 ef | 81 a | 13 ef | 5 d | 19 de | 31 g | 20 fg | 7 e | |

| 0.5 | 56 e | 52 e | 81 a | 12 f | 7 cd | 22 de | 36 f | 21 fg | 8 de | |

| 0.1 | 66 cd | 64 c | 80 a | 15 def | 8 cd | 27 c | 47 d | 27 de | 24 c | |

| ED50 | (μg mL–1) | 17.8 (±0.7) | 6.3 (±0.3) | >1000 | 0.01 (±5.7) | 0.01 (±1.5) | 0.06 (±0.2) | 1.3 (±0.2) | 1.4 (±1.2) | 0.02 (±0.3) |

| AMB | 2.0 | 62 d | 54 e | 80 a | 14 def | 6 cd | 22 d | 37 f | 21 efg | 11 de |

| 1.0 | 62 d | 60 d | 81 a | 16 cde | 7 cd | 26 c | 41 e | 23 efg | 14 d | |

| 0.5 | 64 d | 64 cd | 80 a | 18 cd | 6 cd | 29 c | 49 d | 24 ef | 22 c | |

| 0.1 | 67 bcd | 68 bc | 81 a | 19 c | 9 c | 44 b | 56 c | 31 cd | 65 b | |

| ED50 | (μg mL–1) | >1000 | 25.8 (±0.2) | >1000 | 0.6 (±5.4) | 0.01 (±1.4) | 0.7 (±0.2) | 3.8 (±0.2) | 2.3 (±2.0) | 0.4 (±0.2) |

| NDs | 2.0 | 72 ab | 72 ab | 81 a | 31 ab | 26 b | 57 a | 59 bc | 39 ab | 82 a |

| 1.0 | 73 a | 70 ab | 81 a | 32 ab | 25 b | 58 a | 60 ab | 38 ab | 82 a | |

| 0.5 | 73 a | 69 b | 81 a | 30 b | 30 a | 58 a | 60 ab | 41 a | 80 a | |

| 0.1 | 71 abc | 72 ab | 82 a | 30 ab | 24 b | 59 a | 63 a | 33 bcd | 82 a | |

Data within a column with the same letter are not significantly different (LSD, P < 0.05).

Figure 1.

Petri dishes showing the growth of some of the tested fungi under different treatment conditions.

Regarding the formulation of AMB, in general, greater growth inhibition was observed when AMB was presented as NDs compared with AMB in DMSO. A higher concentration of AMB in DMSO (reflected in a higher ED50) was needed to achieve a reduction in the diameter of the colony compared with AMBNDs. Only in two cases were no significant differences found: with P. cinnamomi, remaining unaffected, and with V. albo-atrum, showing a similar sensitivity with free AMB and AMB-NDs (ED50 lower than 0.1 μg mL–1 in both cases).

Empty NDs had no effect on fungal growth, and no differences were observed with respect to the negative controls.

3.2 Effectiveness against F. oxysporum in chickpea

The results showed some effect in preventive treatments compared with untreated control plants (Fig. 2). Usually, 100% of untreated control plants were dead 18 DAI. However, following preventive irrigation treatment at a concentration of 0.1 mg L–1, nearly 60% of the plants were alive 21 DAI (and 100% alive 15 DAI) (Fig. 2D). In addition, this treatment delayed the development of wilt symptoms, and 30% of the plants were asymptomatic at the end of the experiment (21 DAI). Nevertheless, higher concentrations failed to control the disease, in spite of some good results 15 DAI.

Figure 2.

Effect of AMB-ND treatment on the development of fusarium wilt disease in chickpea.

Some effect was also achieved with preventive foliar treatment at 0.1 mg L–1, with nearly 60% of the plants surviving 15 DAI (Fig. 2B). However, the protective effect was lost with time, and only 15% of the plants survived 21 DAI and showed wilt symptoms.

The remaining treatments did not show a significant effect compared with infected control plants.

3.3 Effectiveness against P. triticina in wheat

Different behaviour was observed, depending on the wheat species. The effect of treatment was almost negligible in the case of bread wheat (Fig. 3A). Only the curative foliar treatment at 10.0 mg L–1 had a significant effect on the percentage of affected leaf area 7 DAI. On the other hand, it reached the same level as the untreated control by 12 DAI.

Figure 3.

Effect of AMB-ND treatment on P. triticina disease severity on wheat plants.

In the case of durum wheat, positive and negative effects were observed, depending on the treatment (Fig. 3B). Preventive foliar treatment at 10.0 mg L–1 was effective, limiting affected leaf area to 25% at 7 and 12 DAI (compared with 31 and 51% from the untreated control respectively). The same effect and levels were achieved by the curative foliar treatment (1.0 mg L–1). On the other hand, irrigation treatments had no effect or a negative effect. Preventive irrigation at all the tested concentrations had a negative synergistic effect on fungal infection, and the percentage of affected leaf area reached higher values than the respective controls. The same happened with the preventive foliar treatment at the lower concentrations (0.1 and 1.0 mg L–1).

4 DISCUSSION

Since its isolation in 1959, AMB has been a preferred antimycotic choice against systemic infection in humans with Candida albicans or Aspergillus fumigatus.9 In addition, it is also an effective antiparasitic agent commonly used to treat infection with protozoal parasites of the genus Leishmania,19 and has been used to control infections in in vitro culture of plant protoplasts.20 The development of nanodevices carrying this drug provides new opportunities for its use against plant pathogens in agriculture and the food industry.6,13 To that end, it is necessary to test AMB effectiveness against different plant pathogenic fungi, because, in spite of its broad spectrum of activity, some cases of resistance have been reported.21

Results from in vitro experiments with nine different isolates of phytopathogenic fungi belonging to six different genera show that susceptibility to AMB is highly dependent not only on the species but also on the forma specialis (f. sp.). In addition, it is highly remarkable that formulation of AMB in NDs can greatly influence the effectiveness of the drug, increasing susceptibility of fungi in most cases. Lower doses of AMB are required (lower ED50) to inhibit growth of most of the tested fungi when the antibiotic is formulated into NDs. The most logical explanation is that NDs protect AMB from degradation by external agents, as shown previously.6 This may be particularly true in cases such as A. fabae, whose growth takes place in the presence of light, a condition in which AMB is susceptible to UV damage. Furthermore, oxidation can adversely affect AMB integrity, and phytopathogenic fungi are known to produce reactive oxygen species (ROS).22 NDs protect against such a possibility by providing a hydrophobic milieu to sequester the antibiotic.6 In the case of F. oxysporum f. sp. melonis, the fungus is insensitive to free AMB, while some effect is seen with AMB-NDs. It may be concluded that formulation of AMB into ND increases the effectiveness of the drug against fungi. At the same time a new question arises: is the increased effectiveness due solely to the protective effect of NDs or are additional factors involved? While answering such a question requires more research, a hypothesis could be suggested: because AMB is embedded in the ND lipidic bilayer, this structure could help the mode of action of the drug. AMB forms complexes with sterols, creating pores in the cell membrane,7,8,19 so the lipidic nature of the NDs could enhance penetration of AMB into the cell membrane, facilitating its interaction with sterols.

The absolute growth insensitivity of P. cinnamomi to AMB, regardless of formulation, is not entirely unexpected. Polyene antimycotics such as piramicin have been extensively used for years in selective media for pythiaceous fungi such as Phytophthora and Pythium spp.23 In fact, AMB has no effect on the growth of Pythium periplocum (except at very high doses), in spite of its ability to inhibit oospore formation.24 AMB has a binding preference for ergosterol, whereupon it forms complexes that lead to pore formation,19 and resistance to this drug has been correlated with a lower content of ergosterol in the fungal membrane.19,21 The simplest explanation, then, would be that ergosterol is absent from cell membranes of P. cinnamomi. However, AMB also binds other sterols, including cholesterol and analogues with a side chain containing more than five carbon atoms.25 Thus, the composition of P. cinnamomi cell membranes may possess unique properties, as this fungus shows no signs of sensitivity to AMB. Or perhaps another mechanism of action of AMB is still pending for clarification, as suggested by Hendrix and Lauder several years ago.24

Regarding the effect of AMB-NDs on fungi infecting living plants, the data show some promising results depending on the pathogen and the plant species. In the case of fusarium wilt in chickpea, the most effective treatment was a preventive dose applied by irrigation (0.1 mg L–1), whereas, for wheat leaf rust, only foliar treatments led to inhibition. The application method is important in both cases, because F. oxysporum f. sp. ciceris is a systemic pathogen that penetrates the roots, so application through irrigation secures direct and rapid contact of AMB-NDs with the fungus. On the other hand, P. triticina is an aerial fungus that develops on plant leaves, and foliar treatments are the best way to administer antimycotic agents to the pathogen. Against fusarium wilt, only preventive treatments had an effect (either foliar or irrigation), whereas wheat rust was affected by preventive or curative treatments provided application was through the leaves and not by irrigation. Fusarium wilt is difficult to control in chickpea using fungicides, and the doses reported in the literature range from 50–250 mg L–1 with strobilurins26,27 to 0.1–0.3% (1000–3000 mg L–1) with fungicides such as benomyl, captan, carbendazim or thiram.28,29 In this respect, if smaller doses (0.1 mg L–1) with AMB-NDs have an effect controlling the disease, treatment with such antimycotic alone or combined with other fungicides could greatly improve fusarium wilt control. In the case of P. triticina, effective treatments have been achieved with 4–25 mg L–1 of strobilurins30 and 0.5–6 mg L–1 of different fungicide combinations such as tebuconazole, triadimenol, carbendazim, etc.31 Because the most effective treatments with AMB-NDs fall within such ranges (1–10 mg L–1), it is possible that it may be used against leaf wheat rust, at least in durum wheat.

Surprisingly, the response of wheat leaf rust to various treatments was highly dependent on the wheat species. Rust infection in bread wheat was nearly unaffected, except for a slight reduction in disease severity 7 DAI with curative foliar treatment at maximum concentration. By contrast, development of rust in durum wheat was affected by treatment either in a negative or positive way. All preventive irrigation treatments, and also the preventive foliar treatment at 1.0 mg L–1, increased disease severity above values observed in control groups. The only reasonable explanation is that, at the concentrations used, AMB is toxic to the plants, making them more susceptible to the fungal attack. There are some reports about negative effects of AMB on photosynthetic proccesses via effects on chloroplasts.32,33 However, in such cases the foliar treatments should have a more negative (and not positive) effect than irrigation treatments. The most suitable explanation, then, is that AMB-NDs affect the wheat plants in another way. AMB can trigger defensive responses and defence gene activation in plant cells that are similar to effects seen by inducers of systemic acquired resistance (SAR).34,35 Such triggering is accomplished by means of stimulation of ion fluxes across plant cell membranes. In this way, inducers of SAR have been shown negatively to affect plants when applied through irrigation,36 probably because of allocation cost.37 AMB-NDs applied as preventive treatment could be affecting the health status of durum wheat plants, making them more sensitive to fungal attack. When applied as preventive treatment and through the roots, AMB-NDs can interact only with the plant cells because the fungus is absent, increasing the possibility of a negative effect. However, when the fungus is present (curative foliar treatment), a certain concentration seems to be optimal for reducing disease severity. Additionally, the highest concentration applied as preventive foliar treatment lowered disease severity to the same extent as the previous one. This could be explained by the possibility that, although some negative effect on the plant is possible, sufficient AMB-NDs are retained in the wheat tissues at the initial stages of infection to maintain SAR activation.

The fact that bread wheat is scarcely affected by AMB-NDs, through either reduction in rust infection or negative effects on the plants, supports the hypothesis that AMB-NDs could be acting as SAR inducers through ion fluxes. The slight reduction in disease severity with the highest concentration of the curative foliar treatment might be explained by the direct effect of AMB-NDs on the fungi. Nevertheless, if no induction of SAR takes places in this case, no effect is observed some days later. With a lower concentration of AMB-NDs, toxic effects are not observed.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by the projects granted by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (MICINN) AGL2008-01467 and EUI2008-00114 and a grant from the US National Institutes of Health (AI 061354).

REFERENCES

- 1.Robinson DKR, Salejova-Zadrazilova G. [11 November 2010];Observatory NANO (2010) Nanotechnologies for Nutrient and Biocide Delivery in Agricultural Production. [Online]. Working Paper Version (April 2010). Available: http://www.observatorynano.eu/project/filesystem/files/Controlled%20delivery.pdf.

- 2.Wang L, Li X, Zhang G, Dong J, Eastoe J. Oil-in-water nanoemulsions for pesticide formulations. J Coll Int Sci. 2007;314:230–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2007.04.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pérez-de-Luque A, Rubiales D. Nanotechnology for parasitic plant control. Pest Manag Sci. 2009;65:540–545. doi: 10.1002/ps.1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nair R, Varghese SH, Nair BG, Maekawa T, Yoshida Y, Kumar DS. Nanoparticulate material delivery to plants. Plant Sci. 2010;179:154–163. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsuji K. Microencapsulation of pesticides and their improved handling safety. J Microencapsul. 2001;18:137–147. doi: 10.1080/026520401750063856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tufteland ML, Selitrennikoff CP, Ryan RO. Nanodiscs protect amphotericin B from ultraviolet light and oxidation-induced damage. Pest Manag Sci. 2009;65:624–628. doi: 10.1002/ps.1712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brajtburg J, Powderly WG, Kobayashi GS, Medoff G. Amphotericin B: current understanding of mechanisms of action. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:183–188. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.2.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamilton-Miller JM. Fungal sterols and the mode of action of the polyene antibiotics. Adv Appl Microbiol. 1974;17:109–134. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2164(08)70556-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Idemyor V. Emerging opportunistic fungal infections: where are we heading? J Natl Med Assoc. 2003;95:1211–1215. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koontz JL, Marcy JE. Formation of natamycin : cyclodextrin inclusion complexes and their characterization. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51:7106–7110. doi: 10.1021/jf030332y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Delves-Broughton J, Thomas LV, Williams G. Natamycin as an antimycotic preservative on cheese and fermented sausages. Food Australia. 2006;58:19–21. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Windholz M, Budavari S, Stroumtsos LY, Fertig MN, editors. TheMerck Index: an Encyclopedia of Chemicals and Drugs. 9th edition. Merk & Co.; Whitehouse Station, NJ: 1996. entry 623. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oda MN, Hargreaves P, Beckstead JA, Redmond KA, van Antwerpen R, Ryan RO. Reconstituted high-density lipoprotein enriched with the polyene antibiotic amphotericin B. J Lipid Res. 2006;47:260–267. doi: 10.1194/jlr.D500033-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ryan RO, Forte TM, Oda MN. Optimized bacterial expression of human apolipoprotein A-I. Protein Exp Purif. 2003;27:98–103. doi: 10.1016/s1046-5928(02)00568-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tufteland M, Ren G, Ryan RO. Nanodisks derived from amphotericin B lipid complex. J Pharm Sci. 2008;97:4425–4432. doi: 10.1002/jps.21325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iruela M, Castro P, Rubio J, Cubero JI, Jacinto C, Millán T, et al. Validation of a QTL for resistance to ascochyta blight linked to resistance to fusarium wilt race 5 in chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.). Eur J Plant Pathol. 2007;119:29–37. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tullu A, Muehlbauer FJ, Simon CJ, Mayer MS, Kumar J, Kaiser WJ, et al. Inheritance and linkage of a gene for resistance to race 4 of fusarium wilt and RAPD markers in chickpea. Euphytica. 1998;102:227–232. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martínez F, Sillero JC, Rubiales D. Resistance to leaf rust in cultivars of bread wheat and durum wheat grown in Spain. Plant Breeding. 2007;126:13–18. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lemke A, Kiderlen AF, Kayser O. Amphotericin B. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2005;68:151–162. doi: 10.1007/s00253-005-1955-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Watts JW, King JM. The use of antibiotics in the culture of non-sterile plant protoplasts. Planta. 1973;113:271–277. doi: 10.1007/BF00390514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ellis D. Amphotericin B: spectrum and resistance. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2002;49:7–10. doi: 10.1093/jac/49.suppl_1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Egan MJ, Wang ZY, Jones MA, Smirnoff N, Talbot NJ. Generation of reactive oxygen species by fungal NADPH oxidases is required for rice blast disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2007;104:11 772–11 777. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700574104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsao PH, Ocana G. Selective isolation of species of Phytophthora from natural soils on an improved antibiotic medium. Nature. 1969;223:636–638. doi: 10.1038/223636a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hendrix JW, Lauder DK. Effects of polyene antibiotics on growth and sterol-induction of oospore formation by Pythium periplocum. J Gen Microbiol. 1966;44:115–120. doi: 10.1099/00221287-44-1-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakamura T, Nishikawa M, Inque K, Nojima S, Akiyama T, Sankawa U. Phosphatidylcholine liposomes containing cholesterol analogues with side chains of various lengths. Chem Phys Lipids. 1980;26:101–110. doi: 10.1016/0009-3084(80)90014-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gullino ML, Minuto A, Gilardi G, Garibaldi A. Efficacy of azoxystrobin and other strobilurins against Fusarium wilts of carnation, cyclamen and Paris daisy. Crop Prot. 2002;21:57–61. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang W, Zhao PL, Liu CL, Chen Q, Liu ZM, Yang GF. Design, synthesis, and fungicidal activities of new strobilurin derivatives. J Agric Food Chem. 2007;55:3004–3010. doi: 10.1021/jf0632987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mukhtar I. Comparison of phytochemical and chemical control of Fusarium oxysporium f. sp. ciceri. Mycopath. 2007;5:107–110. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nikam PS, Jagtap GP, Sontakke PL. Management of chickpea wilt caused by Fusarium oxysporium f. sp. ciceri. Afr J Agr Res. 2007;2:692–697. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cotter HT, May LF, Reichert G, Sieverding E. Fungicidal mixtures. 2003 EP0988790B1.

- 31.Füzi I. Control of leaf rust of winter wheat, Triticum aestivum, in Hungary. Pestic Sci. 1997;49:397–399. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nolan WG, Bishop DG. The site of inhibition of photosynthetic electron transfer by amphotericin B. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1975;166:323–329. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(75)90394-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nolan WG, Bishop DG. Effect of amphotericin b on membrane-associated photosynthetic reactions in maize chloroplasts. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1978;190:473–482. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(78)90301-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jabs T, Tschöpe M, Colling C, Hahlbrock K, Scheel D. Elicitor-stimulated ion fluxes and O2− from the oxidative burst are essential components in triggering defense gene activation and phytoalexin synthesis in parsley. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1997;94:4800–4805. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Katz V, Fuchs A, Conrath U. Pretreatment with salicylic acid primes parsley cells for enhanced ion transport following elicitation. FEBS Lett. 2002;520:53–57. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02759-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pérez-de-Luque A, Jorrín JV, Rubiales D. Crenate broomrape control in pea by foliar application of benzothiadiazole (BTH). Phytoparasitica. 2004;32:21–29. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heil M, Hilpert A, Kaiser W, Linsenmair KE. Reduced growth and seed set following chemical induction of pathogen defence: does systemic acquired resistance (SAR) incur allocation costs? J Ecol. 2000;88:645–654. [Google Scholar]