Abstract

Resiniferatoxin (RTX) is a potent agonist of TRPV1, which possesses unique properties that can be utilized to treat certain modalities of pain. In the present study, systemic intraperitoneal (i.p.) administration of RTX resulted in a significant decrease in acute thermal pain sensitivity, whereas localized intrathecal (i.t.) administration had no effect on acute thermal pain sensitivity. Both i.p. and i.t. administration of RTX prevented TRPV1-induced nocifensive behavior and inflammatory thermal hypersensitivity. There were no alterations in mechanical sensitivity either by i.p. of i.t. administration of RTX. In spinal dorsal horn (L4-L6), TRPV1 and substance P immunoreactivity were abolished following i.p. and i.t. administration of RTX. In dorsal root ganglia (DRG), TRPV1 immunoreactivity was diminished following i.p. administration, but was unaffected following i.t. administration of RTX. Following i.p. administration, basal and evoked CGRP release was reduced both in the spinal cord and peripheral tissues. However, following i.t. administration, basal and evoked CGRP release was reduced in spinal cord (L4-L6), but was unaffected in peripheral tissues. Both i.p. and i.t. RTX administration lowered the body temperature acutely, but this effect reversed with time. Targeting TRPV1 expressing nerve terminals at the spinal cord can selectively abolish inflammatory thermal hypersensitivity without affecting acute thermal sensitivity and can preserve the efferent functions of DRG neurons at the peripheral nerve terminals. I.t. administration of RTX can be considered as a strategy for treating certain chronic and debilitating pain conditions.

Keywords: Pain, inflammatory thermal hypersensitivity, neuropeptides, RTX, TRPV1

Introduction

Transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) is a nonselective cation channel with high calcium permeability and is predominantly expressed in a population of small-diameter sensory neurons.8 TRPV1 is involved in the transduction of noxious chemical stimuli and inflammatory thermal hypersensitivity during tissue damage therefore, targeting TRPV1 is a logical approach to treat certain modalities of pain.7,5,3 Both TRPV1 agonists and antagonists have been shown to be effective in alleviating inflammatory thermal hypersensitivity acting through different mechanisms. TRPV1 agonists can cause calcium-induced desensitization of the receptor at the peripheral or central nerve terminals and prevent generation of action potentials leading to their ability to thwart pain transmission.18, 29, 34, 36, 46 Analgesic effects of localized application of resiniferatoxin (RTX), a potent TRPV1 agonist can be explained by its ability to cause depolarization block of the peripheral or central terminals in the short-term and nerve terminal ablation in the long-term.18,22, 41 Earlier studies have shown that administration of intrathecal and intraganglionic administration of RTX induced long-lasting analgesia, suggesting the possibility of nerve terminal ablation.6,18, 22, 27, 28,34, 50 In DRG-DH neuronal co-cultures and in acute spinal cord or caudal spinal trigeminal nucleus slice preparations, RTX enhanced frequency of spontaneous and miniature excitatory post synaptic currents (EPSCs), without affecting their amplitude.18, 41 However, evoked synaptic currents were inhibited due to slow and sustained activation of presynaptic TRPV1 leading to depolarization block of Na+ channels at the sensory nerve terminals.18

Several TRPV1 antagonists have been synthesized and some of them have entered clinical trials 4, 34, 35, 47. TRPV1 antagonists bring about analgesia by a generalized blockade of the receptor. But a serious limitation that has come to light is that TRPV1 antagonists induce significant increases in the body temperature either by a peripheral or a central mechanism.1, 4, 38 Further, majority of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) and substance P (SP) expressing fibers co-express TRPV1.24 Lack of TRPV1-mediated release of CGRP and SP may affect efferent functions in gastrointestinal, cardiovascular and urinary systems.4 Hence, more focused approach of localized i.t. administration of RTX may be a useful strategy. In fact, intrathecal administration of RTX is in clinical trials for treating pain associated with certain cancers (Study: NCT00804154; Sponsor: National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) and collaborator: National Institutes of Health Clinical Center (CC).

In this study, we intend to demonstrate that localized i.t. administration of RTX selectively affects TRPV1 expressing nerve terminals without affecting the DRG, thereby maintaining the efferent functions of CGRP and SP release. This approach could also limit the side effect of hyperthermia associated with systemic administration of TRPV1 antagonists. Here, we have compared the effects of systemic (i.p.) and localized (i.t.) administration of RTX by studying acute thermal sensitivity, inflammatory thermal and mechanical sensitivities, release of CGRP from peripheral and central nerve terminals, and the changes in body temperatures. The effects of i.p. administration of RTX-induced effects were consistent with the loss of whole DRG neuron. However, localized i.t. administration of RTX only affected TRPV1-mediated afferent sensory functions, but the TRPV1-mediated efferent functions were unaffected.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Experiments were conducted on male Sprague Dawley (250-270 g, n=85) rats purchased from Harlan laboratories, Indianapolis, IN, USA. The animals were housed under standard laboratory conditions, maintained on a normal light-dark cycle and free access to food and water. The experimental procedures used, especially in reference to experimental animals not experiencing unnecessary discomfort, distress, pain or injury have been approved by the Southern Illinois University School of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use committee review panel in accordance with the Panel of Euthanasia of American Veterinary Medical Association. RTX was obtained from Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA and was dissolved in 100% ethanol to make the stock solution (concentration 1mg/ml) which was further diluted in respective solvents. Each rat in i.t. RTX group received intrathecal (L4/L5 intraspinal space) injection of 3.8 μg/kg of RTX in 20 μl of saline.26 Each rat in i.p. RTX group, received intraperitoneal injection of 200 μg/kg/ml of RTX (dissolved in a mixture of 10 % Tween 80 and 10 % ethanol in normal saline.32 Control group received the corresponding vehicle of either treatment group. Animals received RTX injections under isoflurane anesthesia (2% oxygen). Doses for RTX treatment were selected on the basis of previous studies in our (i.t.)18 and other laboratories (i.p.).10,32 All the experiments (capsaicin-/carrageenan-induced nocifensive behavior/inflammatory thermal hypersensitivity, CGRP-release and immunohistochemistry) other than thermal and mechanical pain sensitivities were performed 5 weeks after the treatment with i.t. or i.p. administration of RTX. All the rats were acclimatized to the test conditions 1 hour/day for 5 days before starting the experiments. All the experiments involving behavioral studies were performed by the experimenter who was unaware of treatments. Basal body temperature was recorded daily for all the experimental rats after subcutaneous implantation of temperature sensor (Implantable electronic ID and temperature transponders, Bio Medic data systems, Inc. Delaware, USA).

Behavioral assays

Measurement of thermal sensitivity

Thermal nociceptive responses were determined using a plantar test instrument (Ugo Basile, Camerio, Italy). The rats were habituated (15 minutes acclimation period) to the apparatus that consisted of three individual Perspex boxes on a glass table. A mobile radiant heat source was located under the table and focused onto the desired paw. Paw withdrawal latencies (PWLs) were recorded three times for each hind paw and the average was taken. A timer was automatically activated with the light source, and response latency was defined as the time required for the paw to show an abrupt withdrawal. The apparatus has been calibrated to give a PWL between 9-12 s in untreated control rats. In order to prevent tissue damage a cut-off at 20 s was used.

Measurement of mechanical sensitivity

Mechanical nociceptive responses were assessed using a dynamic plantar anesthesiometer instrument using von Frey hairs (Ugo Basile, Camerio, Italy). Each rat was placed in a chamber with a metal mesh floor and was habituated (15 minutes acclimation period) to the apparatus. A 0.5 mm diameter von Frey probe was applied to the plantar surface of the rat hind paw with pressure increasing by 0.05 Newtons/s and the pressure at which a paw withdrawal occurred was recorded and this was taken as Paw Withdrawal Threshold (PWT). For each hind paw, the procedure was repeated 3 times and the mean pressure to cause withdrawal was calculated. Successive stimuli were applied to alternating paws at 5 min intervals.

Capsaicin-induced nocifensive behavior

Capsaicin-evoked nocifensive behavior in rats was defined as lifting (guarding), licking and shaking of the injected paw following intraplantar capsaicin administration. The number of guarding and licking exhibited by rats was counted and the total duration of this behavior was measured over 5 min immediately after intraplantar administration of capsaicin (2 mM in 20 μl).

Capsaicin-induced thermal hyperalgesia

Capsaicin-induced inflammatory thermal hypersensitivity was determined by intraplantar injection of 100 μM in 100 μl of capsaicin to rat left hind paw. PWLs were determined 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 24 and 48 h after capsaicin injection.

Carrageenan-induced thermal hyperalgesia

After obtaining mean baseline values of PWL to radiant heat, the animals received an intraplantar injection of carrageenan lambda (2%, 100 μl) into the left hind paw. PWLs were determined 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 24 and 48 h after carrageenan injection.

Immunostaining of TRPV1 receptors

Immunofluorescence labeling of TRPV1 receptors in dorsal root ganglia (DRG) neurons and the spinal dorsal horn was performed on three vehicle, three i.t. RTX and three i.p. RTX treated rats to determine the effect of i.t. and i.p. administration of RTX on TRPV1 receptors located on primary afferent neurons and central terminals. Rats were deeply anesthetized with i.p. injection of ketamine (85 mg/kg) and xylazine (5 mg/kg) and perfused intracardially with 100 ml ice-cold normal saline followed by 150 ml 4 % paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.4). The lumbar segment of the spinal cord and corresponding DRG were quickly removed and postfixed for 2 hr in the same fixative solution and cryoprotected in 20% sucrose in 0.1 M PBS for 24 hr at 4°C. Following cryoprotection, 15 μm sections were cut for both spinal cord and DRG using a microtome (Leica CM 1850, North Central Instruments Inc, Plymouth MN-55447).

For TRPV1 receptor immunofluorescence labeling, the sections were rinsed in 0.1 M PBS, permeated with 1% triton X in PBS for 30 minutes. The sections were then blocked in 10% normal donkey serum in PBS for another 30 minutes. The sections were then incubated overnight with the primary antibody (Guinea pig anti-TRPV1 N terminal (dilution 1:1000) Neuromics, Minneapolis, MN, USA and guinea pig anti-SP (dilution 1:200), Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) diluted in PBS containing 1% normal donkey serum, 0.1% triton X-100. Subsequently, sections were rinsed in PBS and incubated (1 hour) with the secondary antibody (Rhodamine donkey anti-guinea pig IgG, Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, Inc. dilution 1:50) diluted in PBS containing 1% normal donkey serum, 0.1% triton X-100. Sections were washed and fixed. A fluorescence microscope was used to view the sections, and areas of interest were photo documented and quantified.18 Three to five sections from each animal were analyzed. For the specificity of TRPV1 primary antibody, we used a peptide raised against the binding epitope of the antibody (Neuromics, Edina, MN, USA). We incubated tissue sections in the presence of primary polyclonal antibody or in the presence of mixture of primary antibody and the peptide. There was no TRPV1 staining when incubated with the peptide, suggesting the specificity of the antibody.

Neuropeptide release assays

Tissue preparation

Paw skin preparation

Three vehicles, three i.t. RTX- and three i.p. RTX-treated rats were anesthetized using isoflurane (5%) and oxygen and animals were sacrificed using CO2. Paw skin was subcutaneously excised obtaining three skin flaps from each rat of a mean weight of 0.30 g (range 0.25–0.40 g). The isolated skin was washed for 30 min in synthetic interstitial fluid (SIF]5 consisting of 107.8 mM NaCl, 26.2 mM NaCO3, 9.64 mM Na-gluconate, 7.6 mM sucrose, 5.05 mM glucose, 3.48 mM KCl, 1.67 mM NaH2PO4, 1.53 mM CaCl2, 0.69 MgSO4, gassed with 95% oxygen and 5% carbon dioxide at 32°C for 30 min.

Spinal cord preparation

Spinal cord was dissected quickly by hydraulic method. Lumbar and cervical portion of spinal cord were collected and were washed for 30 min in SIF gassed with 95% oxygen and 5% carbon dioxide at 32°C for 30 min. Three segments each of 0.10 g (range 0.05–0.15 g) from cervical and lumbar spinal cords of each animal were taken for further elution studies.

Bladder and colon preparations

Urinary bladder (range 0.25–0.50 g) and colon (range 0.25–0.50 g) were quickly dissected and stored at −80° C.

Elution procedures and stimulation

A series of 3 glass tubes were filled with 0.5 ml SIF each and positioned in a temperature controlled shaking bath (32°C). The rel ease experiment was started by transferring the mounted skin flap, spinal cord segment, and stored tissue (bladder and colon) into the first tube. After 5 min incubation, skin flap and spinal cord segments were forwarded to the second tube for another 5 min and thus moved on to third for 5 minutes. After two control samples, stimulation was performed in the third tube with capsaicin (10−5 M, (8-methyl-N-vanillyl-6-nonenamide, Sigma), or anandamide (10−5 M) or inflammatory soup (mixture of bradykinin (10−5 M), histamine (10−5 M) and serotonin (10−5 M) with anandamide (10−5 M) added to normal solution for skin flaps. Only capsaicin (10−5 M) induced stimulation was performed for spinal cord segments. Drugs were prepared as stock solutions in ethanol (100 mM for capsaicin, anandamide, and bradykinin) and diluted to desired concentrations using physiological solution prior to the experiments. The control experiments were performed with the equivalent amounts of the solvent. All the solutions were freshly made before the experiments. For bladder and colon, only basal release of neuropeptides was studied.

Enzyme immunoassays

For CGRP release assay, 200 and 50 μl of elutes were taken from each tube from paw skin and spinal cord samples respectively. Spinal cord elutes were further centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 10 minutes. Samples were mixed immediately after the incubation with 50 μl (paw skin) or 200 μl (spinal cord) of commercial CGRP EIA buffer containing several protease inhibitors. The CGRP content was determined immediately after the end of the experiment using commercially available enzyme immunoassays (CGRP: Bertin Pharma (formerly SPlbio), France, limit of detection= 0.7 pg/ml, range= upto 500 pg/ml). All EIA plates were determined photometrically using a microplate reader.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Student T test was used to compare capsaicin induced nocifensive behaviors in vehicle and RTX treated animals. Descriptive one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare PWL and PWT at given time point for vehicle and RTX-treated animals. Descriptive one way ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey’s HSD was used to compare more than 2 groups. A p value of <0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Behavioral experiments

Thermal and mechanical sensitivities

In order to study the systemic and localized effects, RTX was injected to rats by i.p. or i.t. routes. The effects of i.p. administration have been shown to be as a result of TRPV1 activation and eventually leading to degeneration of the whole DRG neuron.12, 32 However, in this study, we tested the hypothesis that i.t. administration of RTX can selectively affect TRPV1 expressing central terminals in the spinal cord and prevent nociceptive transmission without causing degeneration of the whole neuron. This approach could preserve the DRG cell bodies and the peripheral nerve terminals and maintain efferent functions of sensory neurons. For i.p. administration, a bolus dose of 200 μg/kg/ml of RTX was injected into the peritoneal cavity, and for i.t. administration 3.8 μg/kg/20μl of RTX was slowly injected in the lumbar (L4/L5) intraspinal space under anesthesia. The animals were allowed to recover and there were no significant changes in the general behavior of the animals in both routes of administration.

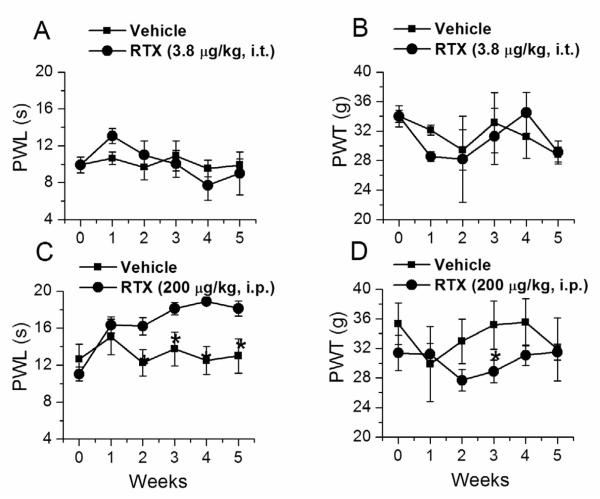

In order to determine changes in thermal pain sensitivity, PWL to a radiant heat source was determined once a week for five weeks. I.t. RTX-administrated animals did not show any significant change in PWL over the period of 5 weeks (vehicle, 10.9±1.61s; i.t. RTX, 10.04±1.4s, n=6) (Fig. 1A). Similarly, we determined PWL in i.p. RTX-administered rats. I.p. RTX-treated animals exhibited increased PWL within one week of RTX administration as compared to vehicle injected controls and became significant at week 2, and remained so over the observed period of 5 weeks (vehicle, 12.5±1.49s; i.p. RTX, 18.9±0.41s, n=6, p < 0.05) (Fig.1C). These experiments suggest that ablation of whole TRPV1 expressing neurons (i.p. administration) results in the loss of thermal pain sensitivity, whereas ablation of only central terminals (i.t. administration) has no effect on thermal pain sensitivity.

Figure 1.

Acute thermal and mechanical sensitivities after i.t. and i.p. RTX-treatment. A. B. Time course of the PWL to noxious heat and PWT to von Frey filament test following i.t. RTX treatment. C. D. Time course of the PWL to noxious heat and PWT to von Frey filament test following i.p. RTX administration. * denotes p<0.05 as compared to vehicle-treated group at respective time points.

Next, mechanical sensitivity was tested by measuring PWT using single filament von Frey test. The PWT was not significantly altered either in i.t. RTX-treated animals (vehicle, 33.13±4.1g; i.t. RTX, 31.27±3.8g, n=6) (Fig. 1B) or in i.p. RTX-treated animals (vehicle, 35.54±3.18g; i.p. RTX, 31.08±1.38g, n=6) (Fig. 1D). This is consistent with the results from other studies that TRPV1 does not mediate mechanical sensitivity.18, 27

Capsaicin-induced nocifensive behavior

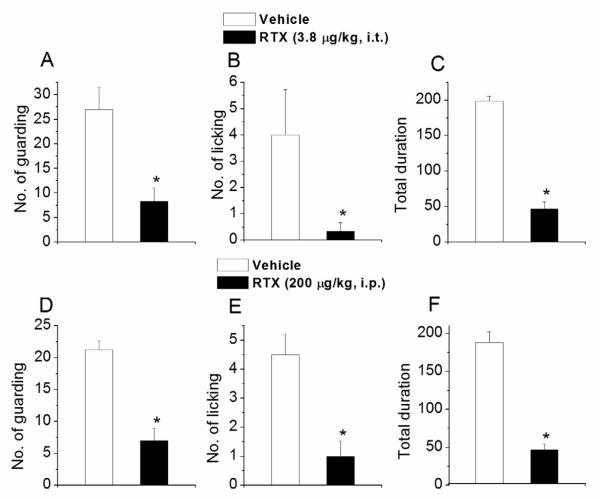

Activation of TRPV1 by intraplantar injection of capsaicin (2 mM in 20 μl) and the resulting characteristic nocifensive behavior (guarding and licking) was used as a test to understand the differences in i.t. and i.p. RTX administration. I.t. RTX administration caused a significant reduction in the number of guarding (vehicle, 27±4.51; i.t. RTX, 8.33±2.73, n=4, p < 0.01) (Fig. 2A) and licking (vehicle, 4±1.73; i.t. RTX, 0.33±0.33, n=4, p < 0.05) (Fig. 2B) behavior. The total duration of the nocifensive behavior was also significantly decreased (vehicle, 198.66 ± 6.96s; i.t. RTX, 47±9.64s, n=4, p < 0.01) (Fig. 2C). Similarly, i.p. administration of RTX significantly reduced the number of guarding (vehicle, 21.25±1.44; i.p. RTX, 7±1.93, n=5, p < 0.01) (Fig. 2D) and licking (vehicle, 4.5±0.7; i.p. RTX, 1±0.53, n=5, p < 0.02) (Fig. 2E) behavior. The total duration of the nocifensive behavior was also significantly reduced (vehicle, 188.25±13.7s; i.p. RTX, 46.87±7.73s, n=5, p < 0.01) (Fig. 2F). These experiments suggest that the effects mediated by TRPV1 activation can be specifically affected by both i.p. and i.t. routes of RTX administration.

Figure 2.

Effect of i.t. and i.p. RTX administration on capsaicin-induced nocifensive behavior. A. B. C. Intraplantar capsaicin-induced guarding, licking and the total duration of nocifensive behavior after i.t. administration of RTX. D. E. F. Capsaicin-induced guarding, licking and the total duration of nocifensive behavior after i.p. administration of RTX. * denotes p< 0.05 as compared to vehicle-treated group.

Capsaicin-induced inflammatory thermal hypersensitivity

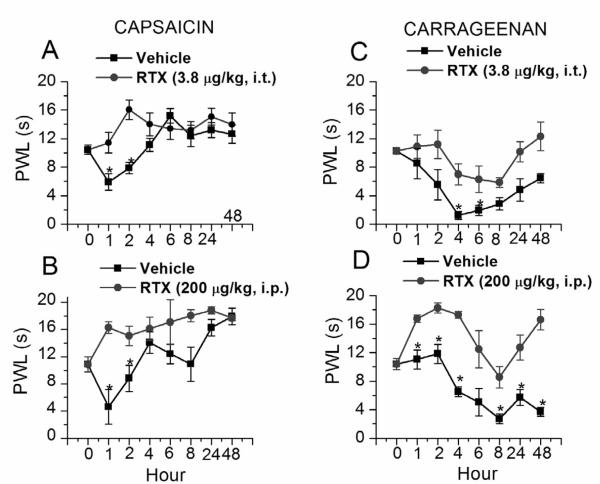

Intraplantar injection of capsaicin (100 μM, 100μl) induced thermal hypersensitivity after 1 h (RTX i.t. vehicle pretreatment, 10.42±0.66s vs. 1h, 5.91±1.16s, n=6, p< 0.05 (Fig.3A); RTX i.p. vehicle pretreatment, 10.88±1.11s vs. 1h, 4.61±2.56s, n=6, p<0.05 (Fig. 3C) due to selective activation of TRPV1. Thermal hypersensitivity started reversing at 2 h, completely reversed at 4 h and remained so up to 48 h (RTX i.t. vehicle 1h, 10.42±0.66s; 48h, 12.63±1.26s, n=6 (Fig.3A); RTX i.p. vehicle 1h, 10.88±1.11s vs. 48h, 17.94±1.23s, n=6, p< 0.05 (Fig. 3C). This may be due to prolonged activation of TRPV1 and resultant increase in intracellular Ca2+ levels leading to desensitization of TRPV1 or due Ca2+ induced TRPV1 expressing nerve terminal loss. Pretreatment with RTX significantly prevented capsaicin-induced thermal hypersensitivity (vehicle 1h, 5.91±1.16s vs. RTX i.t. 1h, 11.41±1.43s, n=6, p< 0.03; vehicle 1h, 4.61±2.56s vs. RTX i.p. 1h, 16.78±0.53s, n=6, p< 0.03 (Fig. 3 A and C). The PWL was also significantly higher in RTX-treated groups at 2h (vehicle 2h, 7.87±0.81s vs. RTX i.t. 2h, 16.05±1.39s, n=6, p< 0.03; vehicle 2h, 8.81±1.94s vs. RTX i.p. 2h, 15.08±1.45s, n=6, p< 0.05 (Fig. 3 A and C). After 2 h up to 48 h there was no significant difference in PWLs of vehicle and RTX-treated animals (vehicle 48h, 12.63± 1.26s vs. RTX i.t. 1h, 13.97±1.62s, n=6; vehicle 48h, 17.94±1.23s vs. RTX i.p. 48h, 17.69±0.37s, n=6 (Fig. 3 A and C). These experiments suggest that capsaicin-induced inflammatory thermal hypersensitivity can be blocked by i.t. or i.p. administration of RTX.

Figure 3.

Effect of i.t. and i.p. RTX administration on inflammatory thermal pain sensitivity. A. B. Capsaicin-induced thermal hypersensitivity following i.t. and i.p. RTX administration. C. D. Carrageenan-induced inflammatory thermal hypersensitivity following i.t and i.p. RTX administration. * denotes p < 0.05 as compared to vehicle-treated group at respective time point.

Carrageenan-induced inflammatory thermal hypersensitivity

Intraplantar injection of carrageenan (1%, 100 μl) produced inflammatory thermal hypersensitivity after 4h (RTX i.t. vehicle pretreatment, 10.25±0.40s vs. 4h, 1.24±0.55s, n=6, p< 0.01; RTX i.p. vehicle pretreatment, 11.40±0.78s vs. 4h, 6.53±0.69s, n=6, p<0.05). Even after 48 h, inflammatory thermal hypersensitivity was quite evident (RTX i.t. vehicle pretreatment,10.25±0.40s vs. 48 h, 6.46±0.64s, n=6, p< 0.05; RTX i.p. control pretreatment, 11.40±0.78s vs. 48h, 3.68±0.63s, n=6, p< 0.01) (Fig. 3 B and D). Pretreatment with RTX significantly reduced carrageenan-induced inflammatory thermal hypersensitivity in rats at 4h (vehicle, 1.24±0.55s vs. RTX i.t., 6.97±1.50s, n=6, p< 0.05; vehicle, 6.53±0.69s vs. RTX i.p., 17.28±0.48s, n=6, p< 0.01) as well as at 48 h (vehicle, 6.46±0.64s vs. RTX i.t.,12.31±2.0s, n=6, p< 0.03; vehicle, 3.68±0.63s vs. RTX i.p.,16.63±1.43s, n=6, p< 0.01) (Fig. 3 C and D). Although, RTX significantly reduced carrageenan-induced thermal hypersensitivity, it did not completely prevent it, suggesting the involvement of other receptors and mechanisms in carrageenan-induced inflammatory hypersensitivity.

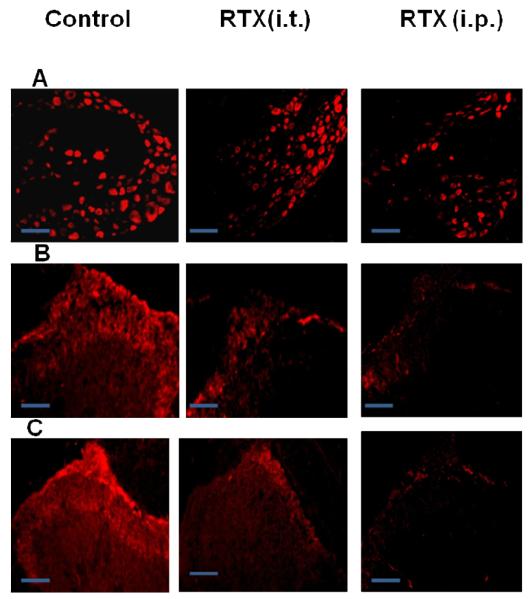

Expression levels of TRPV1 by Immunohistochemistry

Following i.p. administration of RTX, the intensity of staining and the number of TRPV1 expressing DRG neurons were significantly reduced (vehicle, 32.2±4.2%, n=6 from 3 rats; i.p. RTX treated, 15.4±1.6%, n=6 from 3 rats, p< 0.05) (Fig. 4A). Similarly, in the spinal cord sections, TRPV1 expression that was observed only in the sensory nerve terminals (laminae I and II) was abolished (Fig. 4B). However, following i.t. administration of RTX, the intensity of staining and the number of DRG neurons expressing TRPV1 were unaffected (vehicle, 32.2±4.2%, n=6 from 3 rats, i.t. RTX treated, 36.4±3.6%, n=6 from 3 rats) (Fig. 4A). But there was a significant loss of TRPV1 staining in the sensory nerve terminals of the spinal cord (Fig. 4B). This is a significant finding that suggests i.p. administration of RTX ablates the whole neuron, whereas i.t. administration of RTX selectively affects only the central terminals, sparing the neuronal cell bodies. Further, in a separate set of experiments, i.t. and i.p. RTX-treated animals showed significant decrease in SP immunoreactivity in central terminals of afferent neurons in spinal dorsal horn as compared to vehicle-treated animals (Fig. 4C). As SP and TRPV1 are co-expressed, this observation suggests the decrease in TRPV1 immunoreactivity after i.p. RTX and i.t. RTX administration is due to loss of nerve terminals.

Figure 4.

TRPV1 immunostaining 5 weeks after a single administration of i.t. and i.p. RTX. A. TRPV1 staining in lumbar DRG following vehicle, i.t. and i.p. RTX administration in rats. B. TRPV1 staining in dorsal horn of lumbar spinal cord sections following vehicle, i.t., and i.p. RTX administration in rats. C. SP staining in dorsal horn of lumbar spinal cord segment following vehicle, i.t. and i.p. RTX administration in rats.(Scale bar in Fig. 5A :50 μm; Scale bar in Fig. 5B and 5C: 200 μm)

Functional assays of measuring TRPV1-mediated CGRP release

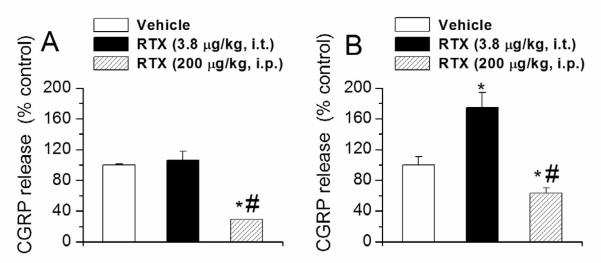

TRPV1 function in the central terminals after RTX administration

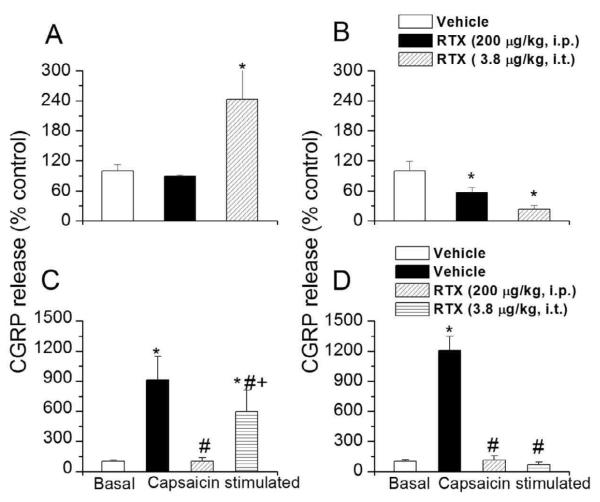

Mean CGRP release in the cervical and the lumbar spinal cord segment of vehicle treated animals were 3081.95 ± 278.91 and 4091.34 ± 179.65 pg/g tissue/5 min, respectively which are consistent with previous studies.44 These values were taken as 100% for further quantification of data. Pretreatment with both i.p. and i.t. RTX significantly decreased basal CGRP release in spinal lumbar region (vehicle, 100±19.2%; i.p. RTX, 57.14±10.1%; i.t. RTX, 22.7±8.6%, n=3, p< 0.05) (Fig. 5 B). Pretreatment with i.p. RTX, although there was a clear trend, did not cause a significant change in basal CGRP release in cervical spinal region (vehicle, 100±12.6 %; i.p. RTX, 89.1±3.1% n=3). However, i.t. RTX did cause a significant increase (vehicle, 100±12.6 %; i.t. RTX, 243.4±61.2%, n=3, p<0.05) (Fig. 5 A). We have no clear explanation for the increase in the cervical region. It is possible that the cervical region may have been exposed to lower concentrations of RTX via the CSF causing an up-regulation of TRPV1 or other receptor function, resulting in enhanced basal CGRP release.

Figure 5.

Effect of i.t. and i.p. RTX administration on basal and evoked CGRP release from spinal cord segments. A. C. Basal (A) and capsaicin-evoked (C) CGRP release from cervical spinal cord segments following i.t and i.p. RTX administration. B. D. Basal (B) and capsaicin-evoked (D) CGRP release from lumbar spinal cord segments following i.t and i.p. RTX administration. * denotes p < 0.05 as compared to vehicle treated group. # denotes p< 0.05 as compared to capsaicin stimulated vehicle. + denotes p< 0.05 as compared to capsaicin-stimulated i.p.-RTX group.

Then, segments were incubated with vehicle or capsaicin (10 μM) to determine TRPV1-mediated CGRP release. Capsaicin-evoked CGRP release in vehicle treated animals was significantly increased in cervical (100±12.6% vs. 913.0±234.6%, n=3, p<0.01) and lumbar (100±19.2% vs. 1209±139.8%, n=3, p< 0.01) (Fig. 5 C and D) regions of the spinal cord. Capsaicin-evoked CGRP release in cervical spinal cord was significantly reduced in i.p. RTX treated animals (vehicle, 913.0±234.6% vs. i.p. RTX, 102±35.4%, n=3, p< 0.02) but not significantly different in i.t. RTX-treated animals (vehicle, 913.0±234.6% vs. i.t. RTX, 596±216.3%, n=3) (Fig. 5C). However, capsaicin-stimulated release of CGRP was significantly reduced in the lumbar region both i.t. (68.68±24.9%, n=3, p < 0.01) and i.p. RTX-treated animals (112±46.3%, n=3, p < 0.01) as compared to vehicle-treated animals (1209±139.8%) (Fig. 5 D).

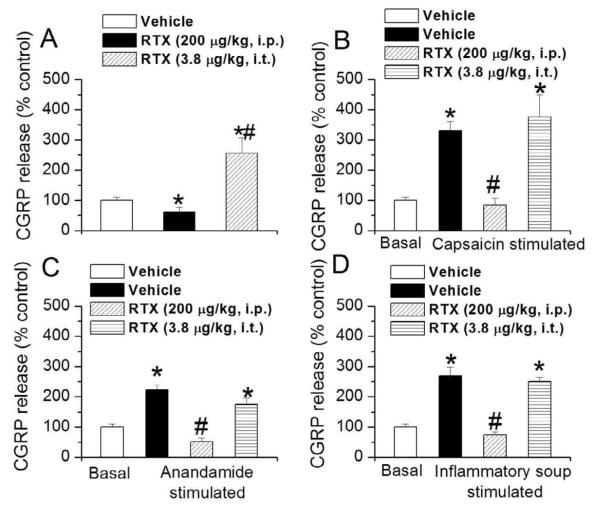

TRPV1 function in the peripheral terminals after RTX administration

Mean CGRP release in the paw skin of vehicle treated animals was 96.65 ± 7.62 pg/g tissue/5 min, which is consistent with previous reports.13, 33 These values were taken as 100% for further quantification of data. Pretreatment with i.p. RTX significantly decreased basal CGRP release in paw skin (vehicle, 100±10.4% vs. i.p. RTX, 60.78±15.6%, n=3, p<0.05), whereas pretreatment with i.t. RTX significantly increased basal CGRP release from the paw skin (vehicle, 100±10.4% vs. i.t. RTX, 255.34±51.0%, n=3, p<0.03) (Fig. 6A). TRPV1 activators/sensitizers significantly (p<0.02) increased CGRP release (capsaicin, 330.7±29.6% (n=3); anandamide, 223.17±17.18% (n=3); and inflammatory soup 269.88±28.3% (n=3), suggesting the role played by TRPV1 in the peripheral terminals. In i.p RTX-treated animals, there was a significant (p<0.05) decrease in capsaicin (84.8±22.5% (n=3)-, anandamide (51.9±11.1% (n=3) -, and inflammatory soup (74.2±10.2%(n=3))-evoked CGRP release in the paw skin, but the release was unaffected in i.t. RTX-treated animals (capsaicin (376.58±73.7% (n=3)-, anandamide (173.42±21.8%(n=3)-, and inflammatory soup (250.15±26.1%(n=3) (Fig. 6 B, C, D). This suggests that affecting TRPV1-expressing central terminals in the spinal cord has no effect on peripheral sensory neuronal functions. Next, we determined CGRP release in other organs innervated by peripheral sensory nerve terminals. Mean CGRP release in bladder and colon of vehicle-treated animals was 3090.34± 52.6 and 1184.73± 127.5 pg/g tissue/5 min respectively. These values were taken as 100% for further quantification of data. I.p. RTX-treated animals exhibited significant decrease in CGRP release from bladder (vehicle, 100±1.69% vs. i.p. RTX, 29±0.34%, n=3, p<0.01) (Fig. 7A) and colon (vehicle, 100±10.70% vs. i.p. RTX, 63.1±6.91%, n=3) (Fig. 7B). As observed with the paw skin tissue, i.t. RTX-treated animals did not exhibit any change in CGRP release in bladder (vehicle, 100±1.69% vs. i.t. RTX, 106±11.80%, n=3) (Fig. 7A), but significantly increased release from colon (vehicle, 100±10.70% vs. i.t. RTX, 175±18.89%, p<0.02) (Fig. 7B). These findings suggest that selective targeting of central terminals does not interfere with the functions of the peripheral terminals, although there was an increase in CGRP release in certain organs, possibly due to increased synthesis and transport of receptors including TRPV1.

Figure 6.

Effect of i.t. and i.p. RTX administration on basal and evoked CGRP release from paw skin tissue (peripheral) following i.p. and i.t. RTX treatment. A. Basal CGRP release in paw skin following i.t and i.p. RTX administration. * denotes p<0.05 as compared to vehicle treated group. # denotes p<0.05 as compared to i.p. RTX-treated group. B. C. D. Capsaicin (B), anandamide (C) and inflammatory soup(D)-evoked CGRP release from paw skin tissue following i.t and i.p. RTX administration. * denotes p<0.05 as compared to vehicle treated group. # denotes p<0.05 as compared to capsaicin- or anandamide- or inflammatory soup-treated tissue.

Figure 7.

Effect of i.t. and i.p. RTX administration on basal CGRP release from urinary bladder and colon tissue following i.t. and i.p. RTX administration. A. CGRP release from urinary bladder tissue. B. CGRP release from colon tissue. * denotes p<0.05 as compared to vehicle treated group. # denotes p<0.05 as compared to i.t. RTX treated group.

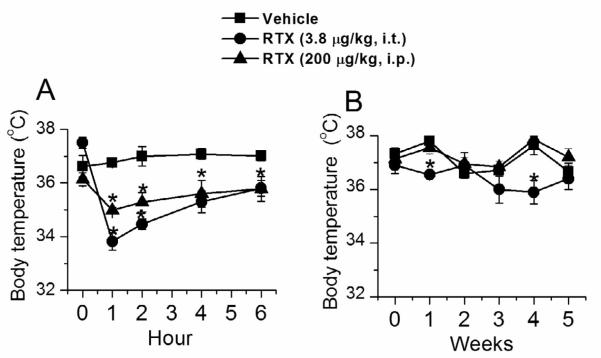

Changes in body temperatures

In both i.p. and i.t. RTX-pretreated animals, there was a significant (p<0.05) decline within 1-2 h after RTX administration (vehicle, 36.76±0.16°C, n=10; i.p. RTX, 33.82±0.2°C n=6 °C; i.t. RTX, 34.98±0.12°C, n=6), which recovered over a period of 6 h (vehicle, 37.01±0.18°C, n=10; i.p. RTX, 35.80±0.3°C, n=6; i.t. RTX, 35.78±0.46°C, n=6) (Fig. 8A). However, in the long-term there was no consistent significant change noted in vehicle, i.p. or i.t. RTX treated animals over the period of 5 weeks (Fig. 8B).

Figure 8.

Changes in body temperature following i.t. and i.p. RTX administration. A. B. Acute (A) and chronic (B) body temperature measurement in rats treated with vehicle, i.t. and i.p. RTX treated rats. * denotes p<0.05 as compared to vehicle treated group. # denotes p<0.05 as compared to i.t. RTX-treated group.

Discussion

In this study, we compared the differential effects of systemic (i.p.) and localized (i.t.) administration of RTX. I.p. administration of RTX ablated TRPV1 expressing neurons as indicated by immunohistochemical staining of dorsal horn of the spinal cord and DRG neurons, whereas i.t. administration only selectively ablated TRPV1 expressing nerve terminals at the dorsal horn without affecting the cell bodies in DRG. The present study also demonstrated that i.t. RTX administration in lumbar region of spinal cord had efficacy similar to i.p. administration against capsaicin-induced nocifensive behavior and thermal inflammatory hypersensitivity, but had no effect on acute thermal and mechanical sensitivities. I.t. and i.p. administration of RTX differentially affected the peripheral (paw skin, colon, and bladder) and central (different segments of spinal cord) terminals; in that TRPV1-mediated release of CGRP at the peripheral terminals was not affected after i.t. administration. Furthermore, no other untoward effects were observed even after administration of 200 μg/kg, i.p., supporting the safety profile of RTX. From these studies, we propose that targeting TRPV1 expressing central terminals is a useful approach to relieve certain modalities of pain, but at the same time preserves peripheral efferent functions of DRG neurons. The present study is in line with an earlier study that intracisternal administration of capsaicin could degenerate central axon terminal and inhibit nociceptive transmission but at the same time retain their specific peripheral functions 16.

Intraplantar administration of TRPV1 agonists elicits a nociceptive response. Initial responses include irritation and burning pain, which can be attributed to binding and activation of TRPV1.46, 52 The proposed mechanism of TRPV1 agonists-induced analgesia is due to receptor desensitization. From our earlier studies, it is clear that RTX selectively activates TRPV1 in a sustained manner.18, 36 The rate of activation of TRPV1 by RTX is slower as compared to capsaicin and protons.36 We have also shown that RTX administration caused a sustained increase in the frequency of spontaneous EPSCs as compared to capsaicin, which induced a desensitizing response. But both RTX and capsaicin caused synaptic failures when evoked EPSCs were recorded due to depolarization block.18,41 Following i.p. administration, the neuronal cell bodies are exposed to RTX resulting in the degeneration of the whole neuron. On the other hand, by i.t. administration only TRPV1 expressing nerve terminals are selectively affected. RTX-induced degeneration of TRPV1 expressing neurons is attributed to constant influx of Ca2+ through the open channels leading to Ca2+-induced cell death.19 However, it is not clear whether the same mechanisms are involved in nerve terminal ablation. We propose that if the dose is well-adjusted, transient nociceptive response could be avoided by slow depolarization of the membrane preventing the generation of action potentials.36 It has been shown that RTX can lead to long-term analgesia in a number of animal models and via different routes of administration: intra-corneal2, intrathecal, 6, 11, 27 epidural 45, intra ganglionic 49, peri-neural 28, intra vesical 23, inter costal 40, and intra-articular.21

In this study, pretreatment of i.p. and i.t. RTX significantly attenuated capsaicin-induced nocifensive behavior, which is expected because of the selectivity of capsaicin towards TRPV1. Further, intraplantar administration of lower concentration of capsaicin induced inflammation and thermal hypersensitivity due to reduced activation threshold. Both i.p. and i.t. RTX administration prevented initial thermal hypersensitivity to capsaicin. Both i.p. and i.t. routes of administration significantly reduced, but not completely abolished carrageenan-induced inflammatory thermal hypersensitivity, suggesting a role of TRPV1 at the same time revealing the involvement of other mechanisms.

Interestingly, i.p. and i.t. RTX administration showed differential effects on acute pain. It is apparent that elimination of TRPV1 expressing nerve terminals affects acute pain. The idea of different modalities of pain carried by different subset of neurons at the levels of peripheral and spinal cord is intriguing. Recently, it has been shown that itch sensation is carried by a subset of neurons at the spinal dorsal horn level.43 It has been shown that distinct subsets of unmyelinated primary sensory fibres mediate behavioral responses to thermal and mechanical stimuli.9 Further, activation of μ-opiod receptors, which are expressed in non-myelinated neurons affects only thermal hypersensitivity, whereas activation of δ-opiod receptors expressed in myelinated sensory neurons affects mechanical hypersensitivity. 34, 39 A possible explanation for our observations is that a subset of sensory nerve terminals that do not express TRPV1 may carry acute pain sensation at the spinal cord level. Further, following i.p. RTX treatment, a small percentage of DRG is still stained for TRPV1 suggesting the minimum requirement of TRPV1 expressing neurons for pain transmission. The preservation of acute pain could not be due to incomplete dosing because in our previous studies, we have determined the effective dose (from 0.045 to 1.9 μg/kg) and found that 1.9 μg/kg is sufficient to cause complete loss of TRPV1 staining.18 Therefore, following i.t. administration of RTX, the acute pain needed for survival can be preserved. Although i.p. administration of RTX significantly alleviated inflammatory thermal hypersensitivity, the mechanical pain sensitivity was not affected. However, Pan et al 32 have reported enhanced mechanical sensitivity after i.p. RTX treatment, but other studies have not confirmed these findings. 30, 48, 49

Using immunostaining studies, we were able to show that i.t. administration of RTX only ablates the central terminals of the primary afferent neurons, but the DRG neuronal cell bodies and the peripheral terminals were preserved, suggesting that sensory efferent functions mediated by TRPV1 would be intact.18 TRPV1 mediates CGRP and SP release at the peripheral nerve terminals, maintains microvascular circulation, and regulates insulin secretion. 15, 37, 47 Further, it has been shown that in long-standing diabetes, TRPV1 expression and functions are downregulated.31 Decreased TRPV1 expression in the heart leads to the inability to carry ischemic pain resulting in an increased incidence of silent myocardial ischemia in patients with diabetes. In studies involving animal models and humans, use of capsaicin and RTX has revealed the importance of TRPV1 expressing sensory neurons in bladder functions.3 TRPV1 also modulates enteric neurotransmission and is involved in early protective mechanisms against colonic inflammation.14, 25 Using TRPV1 knockout mice, it has been demonstrated that CGRP release from the heart is exclusively mediated by TRPV1.42 Lack of TRPV1-mediated CGRP release may affect cardiovascular functions.4,51 In this study, we determined the release of TRPV1-mediated CGRP release in peripheral tissues (paw skin, bladder and colon). Capsaicin-induced CGRP release is used as a measure of TRPV1-mediated functions. I.p. administration of RTX reduced the basal release of CGRP from these peripheral tissues. In contrast, i.t administration of RTX had no effect on basal release; in some experiments an increase was evident. This may be due to an increase in receptor expression as a compensatory mechanism for central terminal loss. There was a complete lack of CGRP release induced by capsaicin, anandamide and inflammatory mediators after i.p. RTX administration, whereas, i.t. administration preserved stimulated CGRP release.

Recent studies have shown the presence of TRPV1 in different brain regions and it has been implicated in CNS functions.20 Therefore, localized administration of TRPV1 agonists or antagonists may affect CNS-related effects. We have studied the basal and TRPV1-mediated neuropeptide release at the lumbar and cervical regions of the spinal cord after i.p. and i.t. administration of RTX at the lumbar region (L4-L6). Basal as well as capsaicin-stimulated release of CGRP was reduced in i.p. RTX-treated animals at both the sites, whereas after i.t administration, CGRP release was significantly lower at the lumbar region, but not in cervical region suggesting that RTX effect is localized to the site of injection.

TRPV1 is also involved in regulation of body temperature. Subcutaneous injection of capsaicin decreased body temperature by 2-3° C and reduced the capacity of rats to withstand a hot environment.17, 46 TRPV1 antagonists increased the body temperature to the same extent.38 This remarkable side effect in clinical trials has led to the abandonment of TRPV1 antagonists as analgesics. In the present study, we recorded acute and chronic changes in body temperature after i.p. and i.t. RTX administration. In both routes of administration, there was an initial decrease in body temperature upto 2 hours (activation of TRPV1) and then returned to control levels. In the chronic 5 week study, there was no significant change in body temperature following both routes of administration. This further underscores the possibility of using i.t. administration of RTX that has no long-term effect in body temperature.

In conclusion, i.p. and i.t. administration of RTX differentially affected acute thermal pain without affecting mechanical pain. Both routes of administration alleviated the inflammatory thermal hypersensitivity. Furthermore, following i.t. administration of RTX, the DRG and the peripheral terminals were intact and the peripheral efferent function of neuropeptide release was unaffected. Localized administration of RTX at different levels of the spinal cord could be a useful strategy in lieu of morphine that causes severe side effects to treat chronic debilitating pain that arises from cancers of the bone and internal organs.

Perspective.

Localized administration of RTX in spinal cord could be a useful strategy to treat chronic debilitating pain arising from certain conditions such as cancer and at the same time could maintain normal physiological peripheral efferent functions mediated by TRPV1.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from National Institutes of Health (DA028017) and EAM award from SIUSOM.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES: There is no conflict of interest among authors.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ayoub SS, Hunter JC, Simmons DL. Answering the burning question of how transient receptor potential vanilloid-1 channel antagonists cause unwanted hyperthermia. Pharmacol Rev. 2009;61:225–7. doi: 10.1124/pr.109.001875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bates BD, Mitchell K, Keller JM, Chan CC, Swaim WD, Yaskovich R, Mannes AJ, Iadarola MJ. Prolonged analgesic response of cornea to topical resiniferatoxin a potent TRPV1 agonist. Pain. 2010;149:522–528. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Birder LA. TRPs in bladder diseases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1772:879–884. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bishnoi M, Premkumar LS. Possible Consequences of Blocking Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid 1. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2010 doi: 10.2174/138920111793937907. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bretag A. Synthetic interstitial fluid for isolated mammalian tissue. Life Sci. 1969;8:319–329. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(69)90283-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown DC, Iadarola MJ, Perkowski SZ, Erin H, Shofer F, Laszlo KJ, Olah Z, Mannes AJ. Physiologic and antinociceptive effects of intrathecal resiniferatoxin in a canine bone cancer model. Anesthesiology. 2005;103:1052–1059. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200511000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caterina MJ, Leffler A, Malmberg AB, Martin WJ, Trafton J, Petersen-Zeitz KR, Koltzenburg M, Basbaum AI, Julius D. Impaired nociception and pain sensation in mice lacking the capsaicin receptor. Science. 2000;288:306–313. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5464.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caterina MJ, Schumacher MA, Tominaga M, Rosen TA, Levine JD, Julius D. The capsaicin receptor: a heat-activated ion channel in the pain pathway. Nature. 1997;389:816–824. doi: 10.1038/39807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cavanaugh DJ, Lee H, Lo L, Shields SD, Zylka MJ, Basbaum AI, Anderson DJ. Distinct subsets of unmyelinated primary sensory fibers mediate behavioral responses to noxious thermal and mechanical stimuli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:9075–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901507106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen SR, Pan HL. Loss of TRPV1-expressing sensory neurons reduce spinal mu opioid receptors but paradoxically potentiate opioid analgesia. J Neurophysiol. 2006;95:3086–3096. doi: 10.1152/jn.01343.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cruz CD, Charrua A, Vieira E, Valente J, Avelino A, Cruz F. Intrathecal delivery of resiniferatoxin (RTX) reduces detrusor overactivity and spinal expression of TRPV1 in spinal cord injured animals. Exp Neurol. 2008;214:301–308. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dogan MD, Patel S, Rudaya AY, Steiner AA, Székely M, Romanovsky AA. Lipopolysaccharide fever is initiated via a capsaicin-sensitive mechanism independent of the subtype-1 vanilloid receptor. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;143:1023–32. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fuchs D, Birklein F, Reeh PW, Sauer SK. Sensitized peripheral nociception in experimental diabetes of the rat. Pain. 2010;151:496–505. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holzer P. Vanilloid receptor TRPV1: hot on the tongue and inflaming the colon. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2004;16:697–699. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2004.00598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Immke DC, Gavva NR. The TRPV1 receptor and nociception. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2006;17:582–591. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jancsó G. Intracisternal capsaicin: selective degeneration of chemosensitive primary sensory afferents in the adult rat. Neurosci Lett. 1981;27:41–45. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(81)90203-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jancsó G, Pupezin J, Van Hook WA. Vapour Pressure of H2 (18)O ice (I) (-17 degrees C to 0 degrees C) and H2(18)O water (0 degrees C to 16 degrees C) Nature. 1970;225:723. doi: 10.1038/225723a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jeffry JA, Yu SQ, Sikand P, Parihar A, Evans MS, Premkumar LS. Selective targeting of TRPV1 expressing sensory nerve terminals in the spinal cord for long lasting analgesia. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7021. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karai L, Brown DC, Mannes AJ, Connelly ST, Brown J, Gandal M, Wellisch OM, Neubert JK, Olah Z, Iadarola MJ. Deletion of vanilloid receptor 1-expressing primary afferent neurons for pain control. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1344–1352. doi: 10.1172/JCI20449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kauer JA, Gibson HE. Hot flash: TRPV channels in the brain. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32:215–224. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kissin EY, Freitas CF, Kissin I. The effects of intra-articular resiniferatoxin in experimental knee-joint arthritis. Anesth Analg. 2005;101:1433–1439. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000180998.29890.B0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kissin I. Vanilloid-induced conduction analgesia: selective, dose-dependent, long-lasting, with a low level of potential neurotoxicity. Anesth Analg. 2008;107:271–281. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e318162cfa3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Komura M, Kuroiwa M, Numazawa K, Yamada T, Hoka S. Anesthetic management of patients with interstitial cystitis during intravesical resiniferatoxin therapy. Masui. 2005;54:149–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lundberg JM, Franco-Cereceda A, Alving K, Delay-Goyet P, Lou YP. Release of calcitonin gene-related peptide from sensory neurons. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1992;657:187–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb22767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Massa F, Sibaev A, Marsicano G, Blaudzun H, Storr M, Lutz B. Vanilloid receptor (TRPV1)-deficient mice show increased susceptibility to dinitrobenzene sulfonic acid-induced colitis. J Mol Med. 2006;84:142–146. doi: 10.1007/s00109-005-0016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mestre C, Pélissier T, Fialip J, Wilcox G, Eschalier A. A method to perform direct transcutaneous intrathecal injection in rats. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 1994;32:197–200. doi: 10.1016/1056-8719(94)90087-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mishra SK, Hoon MA. Ablation of TrpV1 neurons reveal their selective role in thermal pain sensation. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2010;43:157–163. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neubert JK, Mannes AJ, Karai LJ, Jenkins AC, Zawatski L, Abu-Asab M, Iadarola MJ. Perineural resiniferatoxin selectively inhibits inflammatory hyperalgesia. Mol Pain. 2008;4:3. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-4-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Olah Z, Szabo T, Karai L, Hough C, Fields RD, Caudle RM, Blumberg PM, Iadarola MJ. Ligand-induced dynamic membrane changes and cell deletion conferred by vanilloid receptor 1. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:11021–11030. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008392200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ossipov MH, Bian D, Malan TP, Jr, Lai J, Porreca F. Lack of involvement of capsaicin-sensitive primary afferents in nerve-ligation injury induced tactile allodynia in rats. Pain. 1999;79:127–33. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(98)00187-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pabbidi RM, Cao DS, Parihar A, Pauza ME, Premkumar LS. Direct role of streptozotocin in inducing thermal hyperalgesia by enhanced expression of transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 in sensory neurons. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;73:995–1004. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.041707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pan HL, Khan GM, Alloway KD, Chen SR. Resiniferatoxin induces paradoxical changes in thermal and mechanical sensitivities in rats: mechanism of action. J Neurosci. 2003;123:2911–2919. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-07-02911.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pethö G, Izydorczyk I, Reeh PW. Effects of TRPV1 receptor antagonists on stimulated iCGRP release from isolated skin of rats and TRPV1 mutant mice. Pain. 2004;109:284–90. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Premkumar LS. Targeting TRPV1 as an alternative approach to narcotic analgesics to treat chronic pain conditions. AAPS J. 2010;12:361–370. doi: 10.1208/s12248-010-9196-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Premkumar LS, Sikand P. TRPV1: a target for next generation analgesics. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2008;6:151–163. doi: 10.2174/157015908784533888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Raisinghani M, Pabbidi RM, Premkumar LS. Activation of transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) by resiniferatoxin. J Physiol. 2005;567:771–786. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.087874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Razavi V, Chan Y, Afifiyan FN, Liu XJ, Wan X, Yantha J, Tsui H, Tang L, Tsai S, Santamaria P, Driver JP, Serreze D, Salter MW, Dosch HM. TRPV1+ sensory neurons control beta cell stress and islet inflammation in autoimmune diabetes. Cell. 2006;127:1123–1135. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Romanovsky AA, Almeida MC, Garami A, Steiner AA, Norman MH, Morrison SF, Nakamura K, Burmeister JJ, Nucci TB. The transient receptor potential vanilloid-1 channel in thermoregulation: a thermosensor it is not. Pharmacol Rev. 2009;61:228–261. doi: 10.1124/pr.109.001263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scherrer G, Imamachi N, Cao YQ, Contet C, Mennicken F, O’Donnell D, Kieffer BL, Basbaum AI. Dissociation of the opioid receptor mechanisms that control mechanical and heat pain. Cell. 2009;137:1148–1159. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shin JW, Pancaro C, Wang CF, Gerner P. The effects of resiniferatoxin in an experimental rat thoracotomy model. Anesth Analg. 2010;1110:228–232. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181c5c89a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sikand P, Premkumar LS. Potentiation of glutamatergic synaptic transmission by protein kinase C-mediated sensitization of TRPV1 at the first sensory synapse. J Physiol. 2007;1581:631–647. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.118620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Strecker T, Messlinger K, Weyand M, Reeh PW. Role of different proton-sensitive channels in releasing calcitonin gene-related peptide from isolated hearts of mutant mice. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;65:405–410. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sun YG, Zhao ZQ, Meng XL, Yin J, Liu XY, Chen ZF. Cellular basis of itch sensation. Science. 2009;325(5947):1531–1534. doi: 10.1126/science.1174868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sun W, Guo J, Tang Y, Wang X. Alteration of capsaicin and endotoxin-induced calcitonin gene-related peptide release from mesenteric arterial bed and spinal cord slice in 18-month-old rats. J Neurosci Res. 1998;53:385–92. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19980801)53:3<385::AID-JNR13>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Szabo T, Olah Z, Iadarola MJ, Blumberg PM. Epidural resiniferatoxin induced prolonged regional analgesia to pain. Brain Res. 1999;4840:92–98. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01763-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Szallasi A, Blumberg PM. Vanilloid (Capsaicin) receptors and mechanisms. Pharmacol Rev. 1999;51:159–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Szallasi A, Cortright DN, Blum CA, Eid SR. The vanilloid receptor TRPV1: 10 years from channel cloning to antagonist proof-of-concept. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:357–372. doi: 10.1038/nrd2280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tanaka N, Yamaga M, Tateyama S, Uno T, Tsuneyoshi I, Takasaki M. The Effect of Pulsed Radiofrequency Current on Mechanical Allodynia Induced with Resiniferatoxin in Rats. Anesth Analg. 2010;111:784–90. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181e9f62f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tender GC, Li YY, Cui JG. Vanilloid receptor 1-positive neurons mediate thermal hyperalgesia and tactile allodynia. Spine J. 2008;8:351–8. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tender GC, Walbridge S, Olah Z, Karai L, Iadarola M, Oldfield EH, Lonser RR. Selective ablation of nociceptive neurons for elimination of hyperalgesia and neurogenic inflammation. J Neurosurg. 2005;102:522–5. doi: 10.3171/jns.2005.102.3.0522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang Y, Wang DH. Neural control of blood pressure: focusing on capsaicin-sensitive sensory nerves. Cardiovasc Hematol Disord Drug Targets. 2007;7:37–46. doi: 10.2174/187152907780059100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Winter J, Dray A, Wood JN, Yeats JC, Bevan S. Cellular mechanism of action of resiniferatoxin: a potent sensory neuron excitotoxin. Brain Res. 1990;18520:131–140. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)91698-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wong GY, Gavva NR. Therapeutic potential of vanilloid receptor TRPV1 agonists and antagonists as analgesics: Recent advances and setbacks. Brain Res Rev. 2009;60:267–277. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]