Abstract

AIM: To evaluate short- and long-term efficacy of endoscopic balloon dilation in a cohort of consecutive patients with symptomatic Crohn’s disease (CD)-related strictures.

METHODS: Twenty-six CD patients (11 men; median age 36.8 year, range 11-65 years) with 27 symptomatic strictures underwent endoscopic balloon dilation (EBD). Both naive and post-operative strictures, of any length and diameter, with or without associated fistula were included. After a clinical and radiological assessment, EBD was performed with a Microvasive Rigiflex through the scope balloon system. The procedure was considered successful if no symptom reoccurred in the following 6 mo. The long-term clinical outcome was to avoid surgery.

RESULTS: The mean follow-up time was 40.7 ± 5.7 mo (range 10-94 mo). In this period, forty-six EBD were performed with a technical success of 100%. No procedure-related complication was reported. Surgery was avoided in 92.6% of the patients during the entire follow-up. Two patients, both presenting ileocecal strictures associated with fistula, failed to respond to the treatment and underwent surgical strictures resection. Of the 24 patients who did not undergo surgery, 11 patients received 1 EBD, and 13 required further dilations over time for the treatment of relapsing strictures (7 patients underwent 2 dilations, 5 patients 3 dilations, and 1 patient 4 dilations). Overall, the EBD success rate after the first dilation was 81.5%. No difference was observed between the EBD success rate for naive (n = 12) and post-operative (n = 15) CD related strictures (P > 0.05).

CONCLUSION: EBD appears to be a safe and effective procedure in the therapeutic management of CD-related strictures of any origin and dimension in order to prevent surgery.

Keywords: Endoscopic balloon dilation, Crohn’s disease, Strictures, Endoscopy, Gastrointestinal surgery

INTRODUCTION

In the last two decades, the medical therapy for Crohn’s disease (CD) has remarkably improved and the introduction of biological therapies has dramatically changed the therapeutic approach in both adults and children[1,2]. However, CD still displays an unpredictable clinical course with high incidence of recurrence frequently leading to complications such as strictures, fistulas and abscesses[3]. At the time of diagnosis, intestinal strictures may occur throughout the gastrointestinal tract in about 5% of patients, whereas up to one third of the patients develop an intestinal strictures within 10 years of disease activity, with majority of them occurring at the terminal ileum, ileo-colonic, and colonic level[2,4,5].

CD-related strictures is defined as a constant luminal narrowing, which can remain clinically silent or manifest with prestenotic dilatation and obstructive symptoms, such as abdominal bloating, distention, and pain. As the result of the continuous healing response to the chronic inflammation within the intestinal walls, the intestinal stricture induces a progressive narrowing of the lumen and an increased pressure gradient around the stricture, which might ultimately result into the development of internal fistula proximately to the obstruction[6]. Stricture-associated fistulas contribute to increase the disease severity and worsen the clinical management.

CD strictures generally show a poor response to medical therapies, and surgical bowel resection or surgical strictureplasty are often required[5,7,8]. In patients with CD, intestinal surgery is needed for as many as 80% of CD patients, and a permanent stoma is required in more than 10% of CD patients[3]. However, high rate of relapse (defined by recurrence of clinical symptoms) is also observed after surgical resection: 40% at 4 years after bowel resection[9,10], and 50% at 10 to 15 years after ileocecal resection[11,12]. Strictureplasty has also been associated with a risk of stricture relapse in 34% of the cases at 7.5 years[13]. This implies that up to one third of CD patients will undergo more than one surgery in their life course[14-16]. Patients with an early onset disease have an increased risk of surgical relapse and need of repeated resections, which in turn may result in a short bowel syndrome[13,17-20].

Endoscopic balloon dilation (EBD) is a minimally invasive technique that can reduce or delay the need of surgery in patients with CD-related strictures[21,22]. With the new generation of double or single endoscopic balloon enteroscopy, this procedure can be performed at almost any level of the gastrointestinal tract. Moreover, the EBD in CD strictures appears to be a safe technique with a low complication rate (0% to 10%)[22-24]. It has been shown that the technical success rate of the endoscopic balloon dilation is 95%[25-27], with up to 47% of CD patients showing a long-term global benefit, i.e., a surgery-free period at 3 year follow-up[22,24].

In this prospective study, we aimed to assess the effectiveness and safety of the EBD in a cohort of consecutive CD patients with symptomatic intestinal strictures.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study cohort

Twenty-six consecutive CD patients (11 males, 15 females), presenting 27 symptomatic strictures (one patient was treated for two strictures), and complaining up to two intestinal symptomatic obstructive episodes as suspected by plain abdominal X-rays or contrast study in the preceding 6 mo, were prospectively enrolled into the trial between March 2004 and March 2011. Diagnosis of CD in both adult and children was based on widely agreed endoscopic and histological criteria[28,29], and disease classification was done according to the Montreal criteria for adults and Paris criteria for children[30,31]. A detailed personal and family history was obtained from each patient. The clinical assessment of the patients was performed through the pediatric Crohn’s disease activity index (PCDAI) in children, and through the Crohn’s disease activity index (CDAI) in adult[32,33]. An PCDAI ≤ 10 and a CDAI ≤ 150 indicate inactive disease.

Prior to the endoscopic procedure, all patients underwent radiological assessment by abdominal ultrasound with eco-color doppler of mesenteric and the ileocecal region, and magnetic resonance imaging with contrast enhancement to confirm the suspected stricture and to investigate the presence of concomitant fistula or abscess. No exclusion criterion was applied in the selection of strictures to be treated with EBD. Naive and post-surgical strictures, strictures associated with fistula or abscess, and strictures of any length and diameter were included in the study. In all patients surgery was considered for treatment.

EBD technique

Before the endoscopic procedure, all patients underwent the following tests and medications: standard laboratory blood tests including coagulation tests; mechanical intestinal bowel preparation (approximately 36 h before); and liquid diet (starting at least 12 h before).

The endoscopic dilations were performed under unconscious sedation, obtained by administering IV midazolam +/- meperidine or propofol, under constant monitoring of the vital parameters. All procedures were performed by the same endoscopist (de’Angelis GL), and lasted approximately 1 h. The EBD was carried out using Olympus PCF 140 (Olympus, Germany) and Olympus Ileoscopy single balloon SIF 180 (Olympus, Germany) (according to the stricture site).

The EBD was carried out with a hydrostatic Microvasive Rigiflex through the scope balloon system (Microvasive Endoscopic, Boston Scientific Corporation®, Natick, Massachusetts, United States), with a diameter of 15-18 mm. The correct insertion and positioning of the balloon was checked by fluoroscopic control. After reaching the optimal placement through the stricture, the balloon was gradually inflated with water and gastrografin up to 15 mm of diameter, held for 90 s and then deflated. A second inflation up to 18 mm diameter for 90 s was always performed. In case of resilient strictures, the process of inflation was repeated up to 6 times in the same session, reaching progressively larger balloon diameters. Once the balloon dilation was accomplished, a combination of metilprednisolone (40 mg) diluted in 5 mL of normal salin solution were injected intra-lesionally with Olympus single use injector 0, 5 mm (Olympus, Japan). The ultimate step of the procedure consisted in examining the proximal bowel (30 cm above the stricture) in order to detect others possible lesions that were undetected by the pre-procedural assessing imaging.

In combination with underlying treatment, after EBD each patient was treated by administering prednisolone with a dosing scheme determined by body weight: 1.5 mg/kg daily (maximum allowed dose 60 mg daily) for 2 wk, followed by a 4 wk tapering course.

Clinical outcomes

The technical success of the procedure was defined as the passage of the endoscope through the stricture, reaching a diameter of approximately 15 mm. Procedure-related complications were defined as intestinal perforation, and active bleeding requiring surgery or blood transfusions. The long-term clinical success was defined as surgery was avoided all long the follow-up period by obtaining symptom relief with repeated EBD procedures. The short-term clinical success was defined as 6 mo symptom-free period after the EBD. The need of re-dilation was determined based on clinical and imaging criteria in association with persistence or reoccurrence of obstructive symptoms. Surgery was reserved for strictures that did not respond to the medical and the endoscopic therapy.

Ethical considerations

The work carried out was in accordance with the principles laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki for biomedical research involving humans. All adult patients included in the study gave their consent for the use of their clinical data. For children, written consent was obtained from both parents and those older than 12 year signed a statement of assent.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed by using SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 17.0.0 for Macintosh, Chicago, IL, United States). Kaplan-Meier analysis was performed for periods free of surgery and free of endoscopic re-dilation. Regression statistics were used to relate the clinical and demographic variables to the main outcome (i.e., need of surgery). P value ≤ 0.05 was considered significant. Data are expressed as median and range, or mean ± SE, unless otherwise stated.

RESULTS

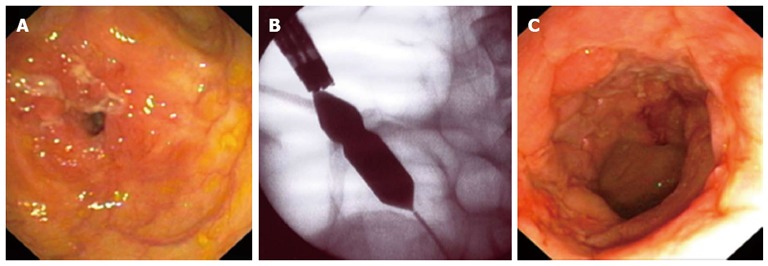

The patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics, and the stricture characteristics are summarized in Tables 1 and 2 respectively. Forty-six EBD were performed for 27 symptomatic strictures occurred in the 26 CD patients. Of these, 15 patients had post-surgical strictures and 11 had naive strictures. The technical success of the endoscopic procedure was achieved in all patients without any endoscopic related complication (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the study cohort

| Clinical characteristics of the study cohort (n = 26) | Data |

| Gender distribution (n) | |

| Male | 11 |

| Female | 15 |

| Pediatric/adult patients distribution (n) | |

| Pediatric | 3 |

| Adult | 23 |

| CD indexes of activity (mean ± SE) | |

| PCDAI (n = 3) | 38 ± 7.2 |

| CDAI (n = 23) | 365 ± 75 |

| Ongoing medical therapy (n) | |

| Azathioprine | 20 |

| Azathioprine + Infliximab | 6 |

| Mean age at the time of the CD diagnosis (yr) | 22.9 ± 2.8 |

| [mean ± SE (range)] | (2-50) |

| Mean age at the time of the occurrence of the first stricture (yr) | 36.8 ± 3.6 |

| [mean ± SE (range)] | (11-65) |

CD: Crohn’s disease; PCDAI: Pediatric Crohn’s disease activity index; CDAI: Crohn’s disease activity index.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of Crohn’s disease-related strictures

| Stricture characteristics (n = 27) | Data |

| Nature of the stricture (n) | |

| Naive | 12 |

| Post-surgical | 15 |

| Location of the stricture (n) | |

| Upper gastrointestinal | 1 |

| Small intestine | 2 |

| Ileo-colonic | 14 |

| Colonic | 10 |

| Mean length (cm) [mean ± SE (range)] | 4.6 ± 0.4 (2-12) |

| ≤ 4 cm (n) | 15 |

| > 4 cm (n) | 12 |

| Mean diameter (mm) [mean ± SE (range)] | 2.5 ± 0.2 (1-6) |

| ≤ 5 mm (n) | 26 |

| > 5 mm (n) | 1 |

| Stricture associated fistula (n) | |

| Yes | 5 |

| No | 22 |

Figure 1.

Images of Crohn’s disease-related stricture in one patient. A: Direct visualization of the ileal stricture; B: Inflation of the endoscopic balloon under fluoroscopic control; C: Direct visualization of the bowel site after the endoscopic balloon dilation.

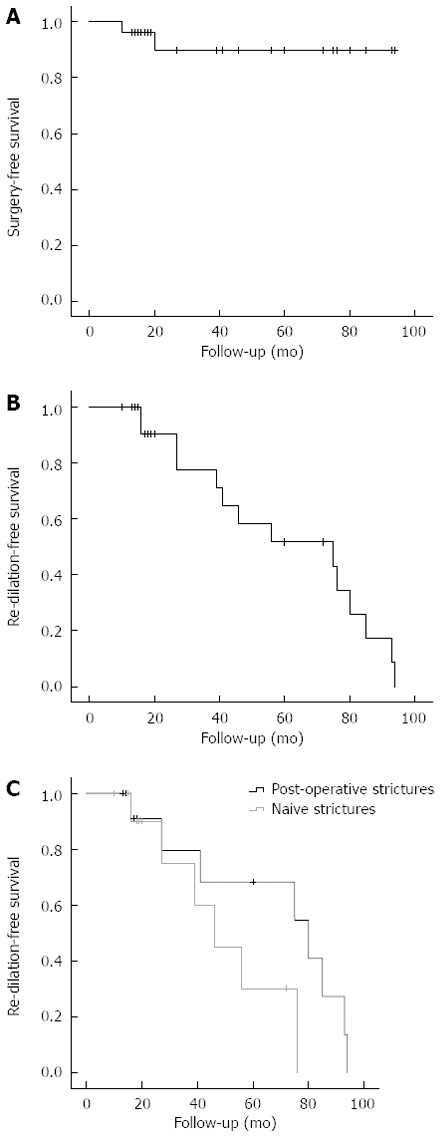

The mean follow-up time of the cohort was 40.7 ± 5.7 mo (range 10-94 mo). All patients survived during the follow-up period. Of the 26 CD patients that were treated with EBD, only two failed to respond to the treatment and underwent elective surgical laparoscopic stricture resection. Both patients requiring surgery presented ileocecal strictures associated with fistula. The overall long-term clinical success rate was 92.6% (24/26 patients remained free of surgery) (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves for intervals free of surgery or endoscopic dilation. A: Kaplan-Meier curve for interval free of surgery after endoscopic balloon dilation or re-dilation; B: Kaplan-Meier curve for interval free of re-dilation during the follow-up period; C: Kaplan-Meier curve for the interval free of re-dilation over the follow-up period for patients with naive (in gray) and post-operative (in black) strictures.

Of the 24 patients who did not undergo surgery all long the follow-up period, 11 patients received only 1 EBD, and 13 required further dilations over time for the treatment of relapsing strictures (7 patients underwent 2 dilations, 5 patients 3 dilations, and 1 patient 4 dilations). The mean time free of re-dilation between the first and the second EBD was 21.2 ± 5 mo. The cumulative percentages of patients free of re-dilation over the entire follow-up period are shown in Figure 2B.

Throughout the study population, the short-term clinical success rate was 81.5% (2 patients required surgery; 3 patients did not have symptom-free 6 mo) after the first EBD. After the second EBD, the clinical success rate was 92.3% (12/13 patients); after the third EBD, the clinical success rate was 83.3% (5/6 patients). Only one patient underwent a fourth EBD showing a clinical success. The subgroup analysis dividing the study population into two groups based on the nature of the strictures, i.e. naive vs post-operative, showed no statistical difference between groups in term of clinical success after repeated EBD. Indeed, after the first dilation, short-term clinical success was obtained in 93.3% of the post-operative strictures and 66.7% of the naive strictures [not significant (NS)]; after the second EBD, success was obtained in 100% of the post-operative strictures and in 80% of the naive ones (NS); after the third EBD, success was observed in 100% of the post-operative strictures and 66.7% of the naive strictures (NS). The cumulative percentages of patients free of re-dilation over the entire follow-up period for both naive and post-operative strictures are shown in Figure 2C.

Of the variables evaluated, the presence of stricture-associated fistula and the stricture location at the ileocecal level resulted significant predictive factors on the long-term negative clinical outcome, i.e., the need of surgery (both P = 0.002). In fact, the 2 strictures that required surgery after the first EBD due to the failure of the endoscopic procedure (i.e., persistency of subocclusion symptoms) were sited at the ileocecal level and were associated with fistula. On the contrary, the sex and age of the patient, the nature of the strictures (naive vs post-surgical), the severity of CD activity, the dimension of the strictures (lengths and diameters), and the medical therapy did not influence the long-term clinical outcomes (Table 3).

Table 3.

Analyses of the influence of the clinical variables on the occurrence of surgery

| Variables | No surgery (n) | Surgery (n) | P value |

| Male sex | 10 | 1 | NS |

| Adult patients | 21 | 2 | NS |

| Naive strictures | 10 | 2 | NS |

| Moderate disease activity | 12 | 2 | NS |

| Strictures length > 4 cm | 11 | 1 | NS |

| Strictures diameters ≤ 5 mm | 24 | 2 | NS |

| Strictures with fistula | 3 | 2 | 0.002 |

| Strictures at the ileocecal level | 3 | 2 | 0.002 |

| Pharmacological therapy (azathioprine) | 18 | 2 | NS |

NS: Not significant.

DISCUSSION

The present study describes the clinical follow-up of a cohort of 26 CD patients presenting with symptomatic strictures and treated with EBD. The EBD appeared to be a safe technique that prevented the need of surgery in 92.6% of the patients during our follow-up period. The endoscopic treatment associated with the medical therapy influenced the natural history of the disease and thus it can be considered an effective strategy in the management of symptomatic strictures in CD patients.

EBD has become more and more used in the treatment of CD strictures since it demonstrated to be a safe and minimally invasive technique, while conserving the intestinal length. At the same time, the medical therapy is largely applied to manage the clinical course of this inflammatory disease and to control its clinical evolution. A combined medical and endoscopic therapy has shown to be effective in the treatment of CD-related strictures[22,34]. However, standardized clinical guidelines and protocols are missing.

Our cohort study presents some points of strength and novelty. In fact, to describe the effectiveness of EBD and its influence of the natural history of the disease, we decided to recruit in the study consecutive CD patients without any strictures related exclusion criterion. Conversely to the other studies[21,22,34,35], we considered strictures of any nature and lengths (up to 12 cm), with and without associated fistula. The objective was to analyze a population that is the most often seen in the everyday clinical practice compared to the highly selected cohorts of patients that are usually described in the literature. Our results demonstrated that the EBD can be effectively used also in CD related strictures longer than 4 cm in order to avoid or postpone surgery. The lengths of the strictures did not appear to be a contraindication for performing EBD as a first line treatment in contrast to previous studies[24,34]. The EBD overall long-term success rate in our study is higher than the values of Hassan et al[34] in a recent systematic review, which reported a cumulative mean success rate of 67% (ranging from 41% to 100%) over an average follow-up time very close to one in the present study. In order to avoid surgery, EBD was repeated-up up to 4 times during the follow with a high short-term clinical success rate after each procedure and a technical success rate of 100% with no procedure-associated complication. This result may be also related to the high-volume endoscopy center in which EBD were performed.

Based on these findings and in accordance with other studies[22,24,34,35], EBD appeared to be a safe procedure with a very low complication rate when an endoscopist experienced in the management of bowel stricture performs it. In our study, we showed that EBD is safe and feasible even in a non-selected sample of CD patients. Moreover, the safety of the procedure may be related to the diameters of the endoscopic balloon used. In our study the 18 mm balloon was the largest applied, for not more than 90 s inflations and no more than 6 dilations per session. If prudency is respected in the selection of balloon dimensions, number of dilations, and progressive inflations, the intra-operative complications may be minimized[22,23,36]. The procedural safety is essential in consideration of the need of frequent re-dilations over time in the same patient in order to obtain and maintain symptomatic relief.

EBD can be considered a valuable and safe alternative of surgical resection, but EBD and surgery must not be seen as mutually exclusive solutions for CD strictures. Rather EBD may be a complementary procedure that should be considered in both adult and pediatric patients in order to reach a symptom-free condition with a low risk associated.

As previously reported, we found that the stricture location at the ileocecal level appeared to be a significant negative predictor on the long-term clinical outcome, i.e., the need of surgery[24]. In our study, also the presence of fistula was associated with the occurrence of surgery. Notwithstanding, three patients with fistulizing phenotype (2 located at the colo-rectal anastomosis and 1 in the sigma), showed good clinical short and long-term outcomes after EBD, suggesting that the analysis results may represent a type II error and that larger groups could provide different results. Studies on EBD in CD patients presenting strictures associated with fistula are scarce in the literature, since the majority of the previously published case series considered the presence of fistula as a patient’s exclusion criterion[21,27,35,37]. Although the paucity of data, in a similar clinical scenario the EBD should not be excluded a priori. Furthermore, it could be used, together with the medical therapy, as an option to bridge the patient to surgery in better performance conditions (e.g., nutrition, inflammatory status), shifting from an emergency to an elective surgery. It is noteworthy that in patients with an adequate nutrition status in which the intestinal obstructive condition has been endoscopically managed (even if suboptimally), the response to surgery and the post-surgical complication rate (e.g., anastomotic leakage) are generally improved[38,39]. The other examined variables seem to not affect the clinical outcomes. However, we were not able to detect which variables are associated with clinical success after only one EBD, and which can predict the need of further dilations. These aspects should be studied in a larger sample of patients.

In our cohort, both naive and post-surgical strictures responded to the EBD treatment, without significant difference on the clinical outcomes as seen by other authors[24,25]. Thus, EBD can be considered a valuable strategy in the management of both naive and post-surgical CD related strictures. In parallel, EBD resulted equally effective in adult and pediatric CD patients. It must be emphasized that the endoscopic management of CD strictures is cardinal in pediatrics because of the long life expectancy of these patients, who would more probably develop a short bowel syndrome if repeated surgical resections are performed. Moreover, many clinical concerns are related to the malnutrition and subsequent failure to thrive that will follow the obstructive condition in children if this is not immediately managed[40].

Interestingly, all our patients were still medically both before and after the endoscopic treatment, mainly with azathioprine and/or biological therapy. Factors determining the development of strictures are not fully understood, but chronic and trans-mural inflammation probably plays a major role[41-43]. Although the lack of data in the literature, azathioprine has been shown to reverse the inflammatory changes at the anastomotic site and to maintaining remission in CD patients[44,45]. Conversely, because of reports of complete obstruction after infliximab in patients with or without initial stricture, its use has been contra-indicated in stenotic forms of CD[46]. Theoretically, the rapid tissue healing induced by infliximab administration may result in marked architectural changes in the intestinal wall, which may lead to wall stricturing. However, strictures do not occur without inflammation, and chronic inflammation per se may lead to strictures. In fact, a long-term inflammatory process sustained by increased cytokine production leads to an excess of fibrotic response. On the other hand, substantial thickening of the mesenchymal layers is observed during mucosal repair. The control of chronic inflammation to prevent fibrosis and stenosis seems more important than the risk of fibrosis induced by treatment, thus justifying infliximab infusions[41]. However, the role of biological therapy in case of CD strictures remains controversial[47,48]. In our cohort, we were not able to define the role and support of the two medical therapies on the clinical outcomes evaluated. With this objective, multicenter, randomized, controlled, blind clinical trials should be performed. The use of EBD is supported not only by the clinical risk/benefit ratio, but also by the costs associated to this procedure. In Italy, the entire EBD procedure (pre-endoscopy exams; hospitalization; medications; balloon dilation kit) is comprised between 1000 and 1200 Euros (reimbursed by the National Health System).

In conclusion, the EBD is not just an attractive treatment option in the management of CD-related strictures. The available literature provides quite enough evidence to support its use. However, clinical guidelines, especially on the combined medical and endoscopical therapy, are still lacking. Time has come to investigate EBD clinical benefits and success in large clinical studies in order to define and standardize the protocol of use.

COMMENTS

Background

Crohn’s disease (CD)-related strictures are scarcely responsive to medical therapy and thus they are mainly treated surgically. Recently, endoscopic balloon dilation has been increasingly used in the treatment of CD-related strictures.

Innovations and breakthroughs

The present study evaluated the efficacy of endoscopic balloon dilation (EBD) in CD-related strictures of any length (up to 12 cm), both naive and post-operative, with or without associated fistula, and in both adult and pediatric patients. Strictures located in both upper and lower gastrointestinal were successfully treated using gastroscope, colonscope or ileoscope according to the stricture site. Their results confirmed that over a mean follow-up period of 40.7 mo multiple endoscopic balloon dilations were safe and effective to manage CD-related strictures.

Applications

The present study supports EBD as a valuable option in the treatment of symptomatic CD patients. Moreover, EBD demonstrated as a safe technique, which can be repeated over time in order to avoid surgery, since it can be performed successfully also in relapsing patients who were previously endoscopically dilated. The associated complications are very rare (none in this study).

Terminology

EBD is an operative endoscopy procedure used to dilate intestinal strictures in unconscious patients. The dilation is carried out with a hydrostatic through the scope balloon system, which, once inserted and positioned through the stricture, is gradually inflated with water, held for 90 s and then deflated to obtain stricture dilation.

Peer review

de’Angelis et al report an interesting series of EBD of strictures in CD. The inclusion of both naive and postoperative strictures with or without associated fistula reflects the usual clinical scenario in CD strictures. Although the number of the cases included in the study is not so large, the conclusions are well presented and discussed. I agree with the authors that until clinical guidelines are available EBD would be a treatment option before surgery in this kind of patients.

Footnotes

P- Reviewers Tsuyoshi K, Sreenivasan S, Di Martino N, Santiago V S- Editor Jiang L L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN

References

- 1.Hanauer SB, Dassopoulos T. Evolving treatment strategies for inflammatory bowel disease. Annu Rev Med. 2001;52:299–318. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.52.1.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Louis E, Collard A, Oger AF, Degroote E, Aboul Nasr El Yafi FA, Belaiche J. Behaviour of Crohn's disease according to the Vienna classification: changing pattern over the course of the disease. Gut. 2001;49:777–782. doi: 10.1136/gut.49.6.777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cosnes J, Gower-Rousseau C, Seksik P, Cortot A. Epidemiology and natural history of inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1785–1794. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.01.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wibmer AG, Kroesen AJ, Gröne J, Buhr HJ, Ritz JP. Comparison of strictureplasty and endoscopic balloon dilatation for stricturing Crohn's disease--review of the literature. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2010;25:1149–1157. doi: 10.1007/s00384-010-1010-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cosnes J, Cattan S, Blain A, Beaugerie L, Carbonnel F, Parc R, Gendre JP. Long-term evolution of disease behavior of Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2002;8:244–250. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200207000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Assche G, Geboes K, Rutgeerts P. Medical therapy for Crohn's disease strictures. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2004;10:55–60. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200401000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Travis SP, Stange EF, Lémann M, Oresland T, Chowers Y, Forbes A, D'Haens G, Kitis G, Cortot A, Prantera C, et al. European evidence based consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn's disease: current management. Gut. 2006;55 Suppl 1:i16–i35. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.081950b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coelho J, Soyer P, Pautrat K, Boudiaf M, Vahedi K, Reignier S, Valleur P, Marteau P. [Management of ileal stenosis in patients with Crohn's disease] Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2009;33:F75–F81. doi: 10.1016/j.gcb.2009.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rutgeerts P, Geboes K, Vantrappen G, Kerremans R, Coenegrachts JL, Coremans G. Natural history of recurrent Crohn's disease at the ileocolonic anastomosis after curative surgery. Gut. 1984;25:665–672. doi: 10.1136/gut.25.6.665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rutgeerts P, Geboes K, Vantrappen G, Beyls J, Kerremans R, Hiele M. Predictability of the postoperative course of Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 1990;99:956–963. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)90613-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sampietro GM, Cristaldi M, Porretta T, Montecamozzo G, Danelli P, Taschieri AM. Early perioperative results and surgical recurrence after strictureplasty and miniresection for complicated Crohn's disease. Dig Surg. 2000;17:261–267. doi: 10.1159/000018845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shore G, Gonzalez QH, Bondora A, Vickers SM. Laparoscopic vs conventional ileocolectomy for primary Crohn disease. Arch Surg. 2003;138:76–79. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.138.1.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dietz DW, Laureti S, Strong SA, Hull TL, Church J, Remzi FH, Lavery IC, Fazio VW. Safety and longterm efficacy of strictureplasty in 314 patients with obstructing small bowel Crohn's disease. J Am Coll Surg. 2001;192:330–37; discussion 330-37;. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(01)00775-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bernell O, Lapidus A, Hellers G. Risk factors for surgery and postoperative recurrence in Crohn's disease. Ann Surg. 2000;231:38–45. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200001000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Michelassi F, Balestracci T, Chappell R, Block GE. Primary and recurrent Crohn's disease. Experience with 1379 patients. Ann Surg. 1991;214:230–28; discussion 230-28;. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199109000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Renna S, Cammà C, Modesto I, Cabibbo G, Scimeca D, Civitavecchia G, Mocciaro F, Orlando A, Enea M, Cottone M. Meta-analysis of the placebo rates of clinical relapse and severe endoscopic recurrence in postoperative Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1500–1509. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.07.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Post S, Herfarth C, Böhm E, Timmermanns G, Schumacher H, Schürmann G, Golling M. The impact of disease pattern, surgical management, and individual surgeons on the risk for relaparotomy for recurrent Crohn's disease. Ann Surg. 1996;223:253–260. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199603000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ryan WR, Allan RN, Yamamoto T, Keighley MR. Crohn's disease patients who quit smoking have a reduced risk of reoperation for recurrence. Am J Surg. 2004;187:219–225. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2003.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scarpa M, Angriman I, Barollo M, Polese L, Ruffolo C, Bertin M, Pagano D, D'Amico DF. Risk factors for recurrence of stenosis in Crohn's disease. Acta Biomed. 2003;74 Suppl 2:80–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krupnick AS, Morris JB. The long-term results of resection and multiple resections in Crohn's disease. Semin Gastrointest Dis. 2000;11:41–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stienecker K, Gleichmann D, Neumayer U, Glaser HJ, Tonus C. Long-term results of endoscopic balloon dilatation of lower gastrointestinal tract strictures in Crohn's disease: a prospective study. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:2623–2627. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.2623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scimeca D, Mocciaro F, Cottone M, Montalbano LM, D'Amico G, Olivo M, Orlando R, Orlando A. Efficacy and safety of endoscopic balloon dilation of symptomatic intestinal Crohn's disease strictures. Dig Liver Dis. 2011;43:121–125. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Couckuyt H, Gevers AM, Coremans G, Hiele M, Rutgeerts P. Efficacy and safety of hydrostatic balloon dilatation of ileocolonic Crohn's strictures: a prospective longterm analysis. Gut. 1995;36:577–580. doi: 10.1136/gut.36.4.577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mueller T, Rieder B, Bechtner G, Pfeiffer A. The response of Crohn's strictures to endoscopic balloon dilation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31:634–639. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blomberg B, Rolny P, Järnerot G. Endoscopic treatment of anastomotic strictures in Crohn's disease. Endoscopy. 1991;23:195–198. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1010654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dear KL, Hunter JO. Colonoscopic hydrostatic balloon dilatation of Crohn's strictures. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;33:315–318. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200110000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thomas-Gibson S, Brooker JC, Hayward CM, Shah SG, Williams CB, Saunders BP. Colonoscopic balloon dilation of Crohn's strictures: a review of long-term outcomes. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;15:485–488. doi: 10.1097/01.meg.0000059110.41030.bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bousvaros A, Antonioli DA, Colletti RB, Dubinsky MC, Glickman JN, Gold BD, Griffiths AM, Jevon GP, Higuchi LM, Hyams JS, et al. Differentiating ulcerative colitis from Crohn disease in children and young adults: report of a working group of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition and the Crohn's and Colitis Foundation of America. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;44:653–674. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31805563f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Assche G, Dignass A, Reinisch W, van der Woude CJ, Sturm A, De Vos M, Guslandi M, Oldenburg B, Dotan I, Marteau P, et al. The second European evidence-based Consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn's disease: Special situations. J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4:63–101. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levine A, Griffiths A, Markowitz J, Wilson DC, Turner D, Russell RK, Fell J, Ruemmele FM, Walters T, Sherlock M, et al. Pediatric modification of the Montreal classification for inflammatory bowel disease: the Paris classification. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:1314–1321. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Satsangi J, Silverberg MS, Vermeire S, Colombel JF. The Montreal classification of inflammatory bowel disease: controversies, consensus, and implications. Gut. 2006;55:749–753. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.082909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hyams JS, Ferry GD, Mandel FS, Gryboski JD, Kibort PM, Kirschner BS, Griffiths AM, Katz AJ, Grand RJ, Boyle JT. Development and validation of a pediatric Crohn's disease activity index. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1991;12:439–447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Friedman S. General principles of medical therapy of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2004;33:191–208, viii. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hassan C, Zullo A, De Francesco V, Ierardi E, Giustini M, Pitidis A, Taggi F, Winn S, Morini S. Systematic review: Endoscopic dilatation in Crohn's disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:1457–1464. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Di Nardo G, Oliva S, Passariello M, Pallotta N, Civitelli F, Frediani S, Gualdi G, Gandullia P, Mallardo S, Cucchiara S. Intralesional steroid injection after endoscopic balloon dilation in pediatric Crohn's disease with stricture: a prospective, randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:1201–1208. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Foster EN, Quiros JA, Prindiville TP. Long-term follow-up of the endoscopic treatment of strictures in pediatric and adult patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:880–885. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181354440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Erkelens GW, van Deventer SJ. Endoscopic treatment of strictures in Crohn's disease. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;18:201–207. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2003.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yamamoto T, Allan RN, Keighley MR. Risk factors for intra-abdominal sepsis after surgery in Crohn's disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:1141–1145. doi: 10.1007/BF02236563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Iesalnieks I, Kilger A, Glass H, Müller-Wille R, Klebl F, Ott C, Strauch U, Piso P, Schlitt HJ, Agha A. Intraabdominal septic complications following bowel resection for Crohn's disease: detrimental influence on long-term outcome. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008;23:1167–1174. doi: 10.1007/s00384-008-0534-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grossman AB, Baldassano RN. Specific considerations in the treatment of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;2:105–124. doi: 10.1586/17474124.2.1.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pelletier AL, Kalisazan B, Wienckiewicz J, Bouarioua N, Soulé JC. Infliximab treatment for symptomatic Crohn's disease strictures. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:279–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brenmoehl J, Falk W, Göke M, Schölmerich J, Rogler G. Inflammation modulates fibronectin isoform expression in colonic lamina propria fibroblasts (CLPF) Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008;23:947–955. doi: 10.1007/s00384-008-0523-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Quinn PG, Binion DG, Connors PJ. The role of endoscopy in inflammatory bowel disease. Med Clin North Am. 1994;78:1331–1352. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(16)30104-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.D'Haens G, Geboes K, Ponette E, Penninckx F, Rutgeerts P. Healing of severe recurrent ileitis with azathioprine therapy in patients with Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1475–1481. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70027-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Riello L, Talbotec C, Garnier-Lengliné H, Pigneur B, Svahn J, Canioni D, Goulet O, Schmitz J, Ruemmele FM. Tolerance and efficacy of azathioprine in pediatric Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:2138–2143. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Louis E, Boverie J, Dewit O, Baert F, De Vos M, D'Haens G. Treatment of small bowel subocclusive Crohn's disease with infliximab: an open pilot study. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2007;70:15–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Samimi R, Flasar MH, Kavic S, Tracy K, Cross RK. Outcome of medical treatment of stricturing and penetrating Crohn's disease: a retrospective study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:1187–1194. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lichtenstein GR, Olson A, Travers S, Diamond RH, Chen DM, Pritchard ML, Feagan BG, Cohen RD, Salzberg BA, Hanauer SB, et al. Factors associated with the development of intestinal strictures or obstructions in patients with Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1030–1038. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]