Abstract

College and university science departments are increasingly taking an active role in improving science education. Perhaps as a result, a new type of specialized science faculty position within science departments is emerging—referred to here as science faculty with education specialties (SFES)—where individual scientists focus their professional efforts on strengthening undergraduate science education, improving kindergarten-through-12th grade science education, and conducting discipline-based education research. Numerous assertions, assumptions, and questions about SFES exist, yet no national studies have been published. Here, we present findings from a large-scale study of US SFES, who are widespread and increasing in numbers. Contrary to many assumptions, SFES were indeed found across the nation, across science disciplines, and, most notably, across primarily undergraduate, master of science-granting, and PhD-granting institutions. Data also reveal unexpected variations among SFES by institution type. Among respondents, SFES at master of science-granting institutions were almost twice as likely to have formal training in science education compared with other SFES. In addition, SFES at PhD-granting institutions were much more likely to have obtained science education funding. Surprisingly, formal training in science education provided no advantage in obtaining science education funding. Our findings show that the SFES phenomenon is likely more complex and diverse than anticipated, with differences being more evident across institution types than across science disciplines. These findings raise questions about the origins of differences among SFES and are useful to science departments interested in hiring SFES, scientific trainees preparing for SFES careers, and agencies awarding science education funding.

Keywords: science faculty roles, higher education, science workforce, science education reform, faculty development

Leadership from university-level scientists with expertise in science disciplines is critical to national efforts in the United States in three arenas of science education: kindergarten-through-12th grade (K–12) science education (1), discipline-based education research `(2), and undergraduate science education reform (3). One mechanism for advancing these three science education arenas is the presence of science faculty with education specialties (SFES) in university science departments. SFES are scientists who take on specialized roles in science education within their discipline (4, 5). Although these hybrid professionals have existed for decades, few studies have assessed the structure, characteristics, and success of the SFES approach to improving science education from within science departments, and these publications have examined mainly undergraduate and master of science (MS)-granting public institutions located in one state (4, 5).

Here, we report data on SFES across the United States and across science departments at public and private universities classified as PhD-granting, MS-granting, and primarily undergraduate institutions (PUIs). Three key findings about the SFES phenomenon emerged. First, our data show that the SFES phenomenon is indeed widespread and growing, with more SFES hired in the last decade than in all previous years combined. SFES respondents were from across the United States, across science disciplines, and across multiple institutions types. Second, although US SFES share common characteristics previously observed (4, 5), we discovered striking differences between SFES at different institution types, including the likelihood they are in tenure-track positions, the extent to which they are engaged in teaching versus research, their level of formal science education training, and their success in obtaining science education funding. Finally, we found that formal training in science education surprisingly gave no apparent advantage to SFES in obtaining funding to support their science education efforts. These key findings have important implications for integrating SFES into college and university science departments and maximizing their efforts to strengthen science education broadly. Each key finding is described in more detail below, as well as supported in further detail in SI Appendix and Tables S1–S9.

Results

Key Finding 1: SFES Are a National, Widespread, and Growing Phenomenon.

SFES in our study represented all major types of US institutions of higher education, including private (26.3%) and public universities (72.7%), community colleges (2.4%), PUIs (22.8%; PUI SFES), MS-granting institutions (22.1%; MS SFES), PhD-granting institutions (50.2%; PhD SFES), and other institution types (2.4%; SI Appendix, Materials and Methods 3 and Additional Analyses 1). SFES in our study were found in 45 states, Washington, DC, and Puerto Rico.

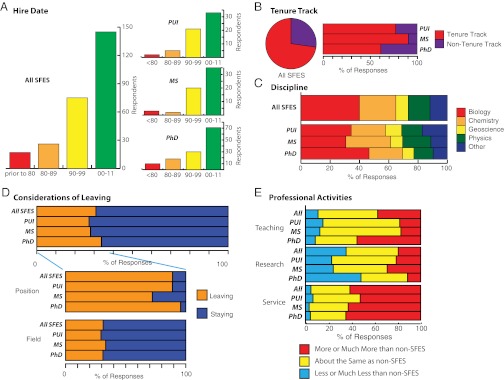

SFES respondents had hire dates from 1966 to 2011 and were predominately recent hires (2000–2011) across institution types (Fig. 1A). SFES were distributed across four science disciplines [biology (39.4%), chemistry (23.9%), geosciences (8.3%), and physics (14.2%)], as well as other science (12.1%) (Fig. 1C and SI Appendix, Materials and Methods 3). In our study, 52.9% of SFES were female, 95.5% were white, and a range of faculty ranks was represented (18.2% assistant, 32.9% associate, and 28.3% full professors). Most SFES (72.7%) were in tenured/tenure-track positions (Fig. 1B), and most SFES (85.1%) did not have tenure before adopting SFES roles.

Fig. 1.

US SFES characteristics across institution types: hiring history, tenure-track positions, representation across disciplines, considerations of leaving, and professional activities. (A) The distribution of SFES hire dates is shown on the Left for all SFES (n = 263) and for only PUI SFES (n = 61, Top), only MS SFES (n = 60, Middle), and only PhD SFES (n = 129, Bottom). (B) The pie chart shows the percentage of all SFES (n = 289) who asserted their position is tenured/tenure-track, and the bars on the Right show these proportions for PUI SFES (n = 66), MS SFES (n = 64), and PhD SFES (n = 145). (C) The proportion of survey respondents affiliated with biology, chemistry, geosciences, physics, or other science departments is shown for all SFES (n = 283), PUI SFES (n = 64), MS SFES (n = 62), and PhD SFES (n = 144). (D) The percentage of SFES who reported seriously considering leaving their job is shown for all SFES (n = 289), PUI SFES (n = 66), MS SFES (n = 64), and PhD SFES (n = 145). Of those seriously considering leaving, their inclination to leave the position and the field is disaggregated below. (E) SFES perceptions of time spent on teaching, research, and service relative to non-SFES departmental peers for all SFES (n = 289), PUI SFES (n = 66), MS SFES (n = 64), and PhD SFES (n = 141) are shown.

SFES across different institution types shared common characteristics that have been previously reported (4, 5). SFES respondents were trained extensively as researchers in basic science (94.8%; Fig. 2A). However, only 43.3% of SFES respondents had formal training in science education (Fig. 2A). Formal training in basic science was defined as postbaccalaureate training by way of a postdoctoral position and/or PhD or MS degree. Formal training in science education was defined as postbaccalaureate training in science education by way of a postdoctoral position, PhD or MS degree, K–12 teaching credential, and/or National Science Foundation graduate fellowship in science education.

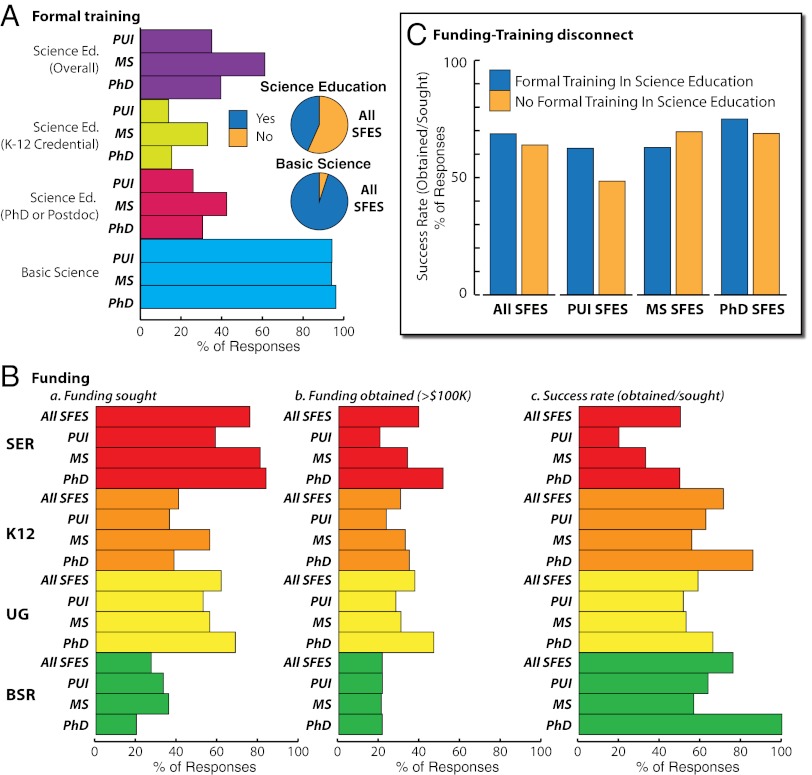

Fig. 2.

Divergence in US SFES characteristics across institution types: formal postbaccalaureate training in science education and basic science; perceptions of funding; funding sought, obtained, and success rate; and funding–training disconnect. (A) On the Left, the percentage of SFES who reported formal training in science education overall (any combination of a K–12 credential, a science education PhD, and/or a science education postdoctoral fellowship), a K–12 credential, a science education PhD or postdoctoral fellowship, and basic science is shown for PUI SFES (n = 66), MS SFES (n = 64), and PhD SFES (n = 145). Pie chart insets represent the proportion of all SFES (n = 289) with formal training in science education (Upper) and basic science (Lower). (B) The percentage of SFES who reported seeking funding for their scholarly work (a, Left), having obtained more than $100,000 in funding (b, Center), and their calculated funding success rates (c, Right) are shown for all SFES (n = 289), PUI SFES (n = 66), MS SFES (n = 66), and PhD SFES (n = 145). (C) The percentage of SFES who both applied for funding in any science education arena and reported obtaining more than $100,000 is disaggregated by formal training in science education for all SFES (n = 153), PUI SFES (n = 26), MS SFES (n = 38), and PhD SFES (n = 89).

For their professional activities (Fig. 1E), SFES were engaged in teaching, research, and service, with the majority of SFES across all institution types (61.5%) perceiving that they spend more time on service than non-SFES. About one-half (52.1%) of SFES reported being the only SFES in their department. Last, some SFES were “seriously considering leaving” their current jobs (30.4%; Fig. 1D). Of these, the vast majority indicated they were considering leaving their position (89.4%) and/or institution (96.5%), rather than the field of science education (31.3%; McNemar’s test χ2 = 44.0, df = 1, P < 0.001).

In summary, common characteristics among SFES included extensive training in basic science research, engagement in both teaching and research, a higher reported service load than non-SFES peers, and a proportion of SFES considering leaving their positions that was similar to previous reports (4, 5).

Key Finding 2: SFES Differed Significantly by Institution Type.

Our data suggest, however, that the SFES phenomenon is more complex and diverse than anticipated. Contrary to common assumptions, SFES differences were more pronounced between SFES at different institution types than in different science disciplines. The analyses presented below focused on three subpopulations: SFES at PhD-granting, MS-granting, and primarily undergraduate institutions, labeled as PhD SFES, MS SFES, and PUI SFES, respectively. These terms signify only the institution type of the SFES, not the level or type of training held by individual SFES. The differences observed were mainly between MS SFES and PhD SFES, with PUI SFES sometimes more similar to one or the other. Four of the most striking and statistically significant differences between SFES at different institution types are detailed below.

SFES Respondents at PhD Institutions Were Less Likely to Occupy Tenure-Track Positions.

Our first striking difference between SFES at different institution types was the significant difference in the structure of SFES positions, in terms of tenure status and rank. Although SFES occupied all faculty ranks, we observed a trend in which PhD-granting institutions had the lowest proportion of full professors compared with MS-granting institutions and PUIs. In addition, a higher combined percentage of instructor/lecturer and “other” ranks were found at PhD-granting institutions, compared with MS-granting institutions and PUIs (P = 0.003). Notably, PhD-granting institutions had the lowest proportion of tenured/tenure-track SFES, compared with MS-granting institutions and PUIs (P < 0.001; Fig. 1B).

These findings suggest that PhD institutions may be more often structuring some SFES positions as non–tenure-track positions compared with other institution types. However, these data appear to be in conflict with the strong tradition of tenure-track, discipline-based education research faculty in physics and chemistry departments. Our results may reflect the large proportion of SFES respondents in biology, although no statistical differences were detected between science disciplines on the measures described above. These data may also support the conclusion that there are subtypes of PhD SFES, for example tenure-track PhD SFES with more emphasis on research versus non–tenure-track PhD SFES with a greater emphasis on teaching.

SFES Respondents at PhD Institutions Report Spending More Time on Teaching and Less Time on Research than Their Non-SFES Peers.

A second striking difference among SFES at different institution types was that they reported different profiles of what their SFES faculty position entailed. When asked about time spent on professional activities compared with non-SFES peers, the profiles of PhD SFES compared with MS and PUI SFES diverged for both teaching and research. PhD SFES had the highest proportion (Fig. 1E) reporting they teach more than non-SFES, whereas only low proportions of MS SFES and PUI SFES reported this (P < 0.001). In addition, PhD SFES had the highest proportion reporting spending less time on research than non-SFES peers, which is about double that for MS SFES and PUI SFES (P < 0.001; Fig. 1E). When directly probed about their conceptualizations of SFES positions across the United States more generally, the majority of SFES characterized SFES positions as a combination of teaching, service, and research, with MS SFES having the highest proportion reporting so, compared with PhD SFES and PUI SFES (P = 0.039). Regardless of institution type, only 13.9% of SFES asserted that SFES positions are primarily teaching positions.

These differences in perceived time spent on teaching and research may be related to the higher proportion of non–tenure-track PhD SFES described above, who may also be in faculty positions with greater emphasis on teaching. Alternatively, primarily undergraduate and MS-granting institutions may be actively constructing SFES positions to be quite similar to non-SFES peers, with similar time spent on teaching versus research, but with a scholarly focus on science education. Regardless of the origins, similarities or differences between SFES and their departmental peers have significant implications for the enfranchisement of SFES in departmental decision making, the extent to which their science education efforts are integrated into the culture of the department, and the likely longevity of these SFES positions.

SFES Respondents at MS Institutions Were More Likely to Have Formal Science Education Training.

A third striking difference among SFES across institution types was whether or not they had formal science education training and the nature of that training (Fig. 2A and SI Appendix, Additional Analyses 2). A significantly higher proportion of MS SFES (60.9%) had formal training in science education than did PhD SFES (39.3%) or PUI SFES (34.8%; χ2 = 11.0, df = 2, P = 0.004). These findings suggest that MS-granting institutions may be more actively hiring and retaining SFES with formal training in science education than are other institution types. This concentration of science education-trained SFES at MS-granting institutions is intriguing, and its origins are unclear.

SFES Respondents at PhD Institutions Were More Likely to Have Obtained Science Education Funding.

Finally, the fourth striking difference among SFES at different institution types was multiple significant differences among PhD, MS, and PUI SFES in obtaining science education funding (Fig. 2B). Funding sought, obtained, and success rate by SFES were examined for the three key science education arenas—K–12 science education, discipline-based education research, and undergraduate science education reform, as well as basic science research (SI Appendix, Additional Analyses 2). SFES across all institution types reported applying for funding in all three arenas of science education (Fig. 2A). In terms of those who applied for and obtained funding, the success rate for PhD SFES was significantly higher than for MS and PUI SFES in all three science education arenas: undergraduate science education (P = 0.013), K–12 science education (P = 0.026), and discipline-based science education (P < 0.001; Fig. 2Bc). Over 80% of SFES in our study reported seeking funding in at least one of these science education arenas, and only 24.2% reported seeking funding in all three (Fig. 2Ba). Within each institution type, the highest proportion of SFES sought funding for science education research, whereas the lowest proportion sought funding for basic science research.

These data suggest that, as a group, PhD SFES respondents were most likely to have obtained science education funding, even though PhD SFES as a group are least likely to have formal science education training and least likely to be in a tenure-track, higher rank faculty position. That said, if there are subtypes of SFES at PhD-granting institutions, it may be primarily a subset of PhD SFES—perhaps those who have formal training in science education, are in tenure-track positions, and have job expectations that emphasize research—who are obtaining science education funding.

Key Finding 3: Formal Training in Science Education Is Not Associated with Success in Obtaining Science Education Funding.

To test the hypothesis presented above that a subset of PhD SFES may be driving statistically higher rates of funding success, we examined the relationship between science education funding success and formal science education training among all SFES. For the purpose of this analysis, we have defined funding success as cumulatively obtaining $100,000 or more in their current position. Surprisingly, we found that SFES with formal training in science education had no apparent advantage in obtaining funding in science education. For SFES who applied for science education funding in any of the three arenas, formal training in science education appeared to have no impact on obtaining funding over $100,000 (Fig. 2C). Among all SFES, 68.7% of those with formal science education training successfully obtained funding, compared with 63.9% of those without formal science education training (Fig. 2C; P = 0.547), regardless of institution type.

To investigate which characteristics of SFES were predictors of science education funding success, we performed logistic regression analysis (SI Appendix, Additional Analyses 3). The following six predictive factors were tested: (i) applied versus did not apply for science education funding, (ii) formally trained versus not formally trained in science education, (iii) tenure-track versus non–tenure-track position, (iv) disciplinary field (biology, chemistry, geology, physics, other science), (v) institution type (PhD, MS, PUI), and (vi) prior success versus lack of success in obtaining basic science research funding. We found four factors that were statistically related to science education funding success. These factors were that an SFES (i) had applied for science education funding (P < 0.001), (ii) was in a tenure-track position (P = 0.017), (iii) was at a PhD-granting institution (P = 0.008), and (iv) had obtained basic science research funding (P = 0.022). We were unable to detect significant effects due to disciplinary field (P = 0.582), and quite strikingly, formal training in science education (P = 0.302).

These data support the conclusion that formal science education training currently provides no advantage for SFES in obtaining science education funding. Rather, funding success is most closely associated with SFES in tenure-track positions at PhD institutions who have also obtained basic science research funding. Because these characteristics are not associated with PhD SFES respondents as a group, our data may support the conclusion that only a particular subset of PhD SFES in unique SFES positions may be experiencing science education funding success among PhD SFES more generally. Finally, the disconnect between formal science education training and science education funding success would suggest that funding is perhaps being awarded to SFES regardless of training, which has significant implications for the impact of these science education funding efforts.

Discussion

Understanding the Growing SFES Phenomenon.

The widespread and growing occurrence of SFES across the United States confirms that the SFES phenomenon is robust, extensive, and expanding. What is driving this growth, and are national policy agencies providing explicit direction and support? What has been the impact of SFES on science education, and what factors promote SFES success? Perhaps individual institutions and/or science departments are engaging in science education by hiring, in most cases as shown by the data, a single SFES within a department to promulgate the transformation across a department. How effective is this model, and are there other models that bear emulating (e.g., hiring a cohort of SFES)? Also, contrary to some beliefs, SFES respondents as a group do not hold primarily teaching positions or primarily discipline-based education research positions, and it is important that science education stakeholders realize and acknowledge these areas of expertise are not the same. Increasing the number of SFES positions may not result in improvements in science education if those positions suffer from misalignment between SFES expertise and the expectations for the position.

Exploring the Origins of SFES Differences by Institution Type.

Unexpected differences in SFES profiles across institution types in our sample indicate that the SFES phenomenon may be context dependent, with the contrasts between MS SFES and PhD SFES being most strongly evident, whereas PUI SFES were typically similar to one or the other. Variation in SFES characteristics by institution type raises questions about the origins of these differences. SFES at MS-granting institutions show the highest proportions of SFES who are tenured/tenure-track, higher ranked, trained in science education, and report professional expectations being similar to non-SFES peers at their institutions. Perhaps MS-granting institutions are constructing SFES positions to be typical tenure-track, science faculty positions and explicitly envisioning SFES as providing expertise in an area of specialization (education) analogous to specialization in other areas (e.g., ecology or organic chemistry).

PhD SFES respondents show lower proportions of SFES who are tenured/tenure-track and have training in science education and higher proportions of SFES reporting teaching more and engaging in less scholarly activity than non-SFES peers. Despite examples to the contrary among discipline-based education researchers, one wonders if there are a subset of PhD SFES positions that are being constructed as non–tenure-track, primarily teaching positions? Perhaps PhD SFES are simply a more heterogeneous population than SFES at other institution types. If so, what are the implications stemming from the greater frequency of funding being awarded to SFES at PhD institutions? Perhaps science education funding is being directed toward PhD SFES who are driving science education reform, such as transforming undergraduate science curriculum. However, if such funding is being directed toward academic climates in which PhD SFES occupy less enfranchised roles within PhD science departments, then the resources may not substantially improve science education at these institutions.

PUI SFES respondents show the lowest proportion of Hired-SFES (SI Appendix, Materials and Methods 3), which may indicate that the SFES phenomenon is only recently emerging in this context. However, PUI SFES, along with MS SFES, have the highest proportion reporting professional expectations being similar to non-SFES peers. Perhaps PUI science faculty generally view science education as integral to their occupation, and little distinction exists between SFES and non-SFES at PUIs.

It may well be that variation in SFES profiles is being driven by intentional decision making and leadership at the institutional, college, and/or department level. However, individuals with specific characteristics may be gravitating toward institution types based on personal choice, although the structure of the position and culture of the institution may be influencing that choice. Future research, both within a single institution and across multiple institutions, that investigates a wider range of stakeholder perspectives (SFES, administrators, and non-SFES peers) is needed to understand what may be driving these institution-type differences in SFES positions and how institutional culture may be supporting or limiting science education efforts.

Examining SFES Training and Funding for Advancing Science Education.

Surprisingly, formal training in science education provided no advantage in obtaining science education funding among our respondents. This finding raises significant questions about the SFES phenomenon and major concerns for national efforts to improve science education. If training is not a benefit in seeking funding to support SFES science education efforts, then what are the reasons? Perhaps current science education training pathways are insufficient and need to be strengthened, more formalized, and/or more extensive. National policy makers and science education agencies could evaluate and/or develop realistic training models that are more effective than current pathways. If SFES with training are no more successful in obtaining funding for their scholarly efforts than those without training, then possibly fewer trained SFES have the ability to meet tenure and promotion criteria. More significantly, fewer trained SFES are directing the funding resources for science education.

Interestingly, obtaining science education funding was associated with three meaningful SFES characteristics: tenured/tenure-track position, at a PhD institution, and previous funding for basic science research. PhD SFES in our sample, however, have the most individuals who are in non–tenure-track, primarily teaching positions. Potentially the vast majority of funding is being channeled toward academic climates that are less likely to support SFES with the status to transform a science department. As a result, current funding efforts to advance science education may be achieving limited success.

In summary, specialized faculty positions focused on science education within science departments are widespread and growing, but with unexpected variations at different institution types and no clear advantage of having formal science education training in obtaining science education funding. These data suggest multiple hypotheses about SFES to be tested in future interview-based and randomized sample survey studies. Clearly, these national findings have implications for the role and impact of SFES at institutions of higher education, especially in terms of determining SFES training and hiring criteria, formulating national science education policy regarding higher education efforts to improve science education, and examining the impact of the current distribution of science education funding.

Methods

Sample and Data Collection.

Due to a lack of a sampling frame for SFES in the United States, a nationwide outreach was launched between September 2009 and March 2011 to build a pool of SFES for this study. Extensive announcements through e-mail broadcasts and flyers were sent to a dozen professional societies in the sciences and multiple science education societies. A total of 973 individuals registered in our online registry. Of these registrants, individuals who self-identified that they were not SFES (n = 102), who were located outside of the United States (n = 22), or who were identified as high school educators (n = 8) were excluded from the subject pool. The remaining 841 SFES in the United States were invited by e-mail to complete a 95-question, face-validated, anonymous, online survey (SI Appendix, Survey Instrument) and also asked to recruit additional likely SFES in the United States to participate. No compensation was provided to either the participants or their referrals. Between March and June 2011, a total of 427 individuals participated in the online survey, producing an effective sample of 289. The rest (n = 138) were not included in the analysis because their questionnaires were incomplete or they did not qualify for our definition of SFES (SI Appendix, Materials and Methods 1). These individuals participated without compensation and remained anonymous throughout data collection and analysis. Completion of data collection was based on the rationale that, upon survey closure, the initial participant population of 427 provided a sufficiently large sample to discern effect sizes greater than 17% at the P < 0.05 level, for comparisons within the respondent population. Although this was a convenience sample, our subjects reflected a purposefully broad spectrum of our target population (SI Appendix, Materials and Methods 1).

Analyses presented here are based on data from 289 individuals with n values for responding SFES varying per question; surveys from an additional 138 respondents were not usable because they did not meet the study inclusion criteria (SI Appendix, Materials and Methods 1). For operational definitions of categories, see SI Appendix, Materials and Methods 3. For additional analyses and data tables, see SI Appendix, Additional Analyses and Tables S1–S9.

Statistical Analyses.

We completed Pearson’s χ2 and McNemar’s (6) tests to compare SFES subpopulations at the P < 0.05 level. Pearson χ2 tests of independence were used to assess whether paired observations, e.g., responses of SFES from different institution types, were independent of each other. McNemar's test was used to compare paired proportions, such as comparing SFES from different institution types and disciplines who were “seriously considering leaving” their “position” or “field.” Logistic regression analysis was used to test for factors associated with funding success in science education (SI Appendix, Materials and Methods 2). Probability values less than 0.05 were used to reject the null hypothesis for all statistical tests. To describe a more complete picture of SFES at each institution type, non-tenured/tenure-track SFES were included in the descriptive and statistical analyses. Inclusion of non-tenured/tenure-track SFES did not change statistical significance at the P < 0.05 level. Resulting statistical differences represented comparisons among SFES respondents with different characteristics, which may or may not generalize to all US SFES.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Sheldon Zhang for survey methodology support, and Andrew Shaffner for statistical analyses support. M.T.S. thanks the Scholarly Activities Committee of the College of Science and Health at Utah Valley University for funding. The authors acknowledge the National Science Foundation's support [Division of Undergraduate Education (DUE)-1228657]. Finally, we thank all SFES who participated in this research and our families for their ongoing patience and support.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1218821110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1. Achieve, Inc. (2012) Next Generation Science Standards. Available at www.nextgenscience.org/. Accessed May 28, 2012.

- 2.Singer SR, Nielsen NR, Schweingruber HA, editors. Discipline-based education research: Understanding and improving learning in undergraduate science and engineering. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, National Research Council; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3.President's Council of Advisors for Science and Technology 2012. Engage to Excel: Producing One Million Additional College Graduates with Degrees in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics. Available at www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/microsites/ostp/pcast-engage-to-excel-final_2-25-12.pdf. Accessed March 28, 2013.

- 4.Bush SD, et al. Science faculty with education specialties. Science. 2008;322(5909):1795–1796. doi: 10.1126/science.1162072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bush SD, et al. Investigation of science faculty with education specialties within the largest university system in the United States. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2011;10(1):25–42. doi: 10.1187/cbe.10-08-0106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McNemar Q. Note on the sampling error of the difference between correlated proportions or percentages. Psychometrika. 1947;12(2):153–157. doi: 10.1007/BF02295996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.