Abstract

Despite major advances in our understanding of many aspects of human papillomavirus (HPV) biology, HPV entry is poorly understood. To identify cellular genes required for HPV entry, we conducted a genome-wide screen for siRNAs that inhibited infection of HeLa cells by HPV16 pseudovirus. Many retrograde transport factors were required for efficient infection, including multiple subunits of the retromer, which initiates retrograde transport from the endosome to the trans-Golgi network (TGN). The retromer has not been previously implicated in virus entry. Furthermore, HPV16 capsid proteins arrive in the TGN/Golgi in a retromer-dependent fashion during entry, and incoming HPV proteins form a stable complex with retromer subunits. We propose that HPV16 directly engages the retromer at the early or late endosome and traffics to the TGN/Golgi via the retrograde pathway during cell entry. These results provide important insights into HPV entry, identify numerous potential antiviral targets, and suggest that the role of the retromer in infection by other viruses should be assessed.

Keywords: cervical cancer, tumor virus, RNA interference, intracellular trafficking

Infectious entry of many nonenveloped viruses is poorly understood. These viruses cannot use membrane fusion to penetrate the plasma membrane or escape endocytic compartments and have instead evolved entry strategies involving interactions between viral capsid proteins and cell factors that carry out cellular functions (1). Thus, studies of virus entry will not only elucidate an essential step in virus infection, but also provide insight into important cellular processes.

Papillomaviruses are small, nonenveloped, DNA viruses that infect epithelial cells. High-risk human papillomaviruses (HPVs) such as HPV16 are associated with 5% of all human cancers (2, 3). Although prophylactic vaccines that target certain HPV types have been deployed, high-risk HPV will remain responsible for substantial disease burden for decades because of poor vaccine utilization and limited vaccine efficacy in people who are already infected by HPV. Understanding HPV entry will suggest novel strategies for blocking HPV infection and provide important new insights into the cellular machinery involved in this complex process.

Many aspects of productive HPV replication are obscure. HPV capsids are composed of 72 pentamers of the major capsid protein L1, as well as at least 12 molecules of the minor capsid protein L2, which is largely buried in the intact capsid (4). After an initial association of L1 with heparan sulfate proteoglycans, capsids undergo conformational changes, and proteolytic cleavage occurs in L2 (5-7). HPV is then thought to be transferred to an as-yet-unidentified cell-surface receptor, followed by endocytosis and intracellular trafficking (8–15). Cyclophilin B and the proteases furin and γ-secretase play essential but not clearly understood roles during HPV entry (16–19). After HPV is internalized, capsid disassembly is initiated in the endosome by acidification (11, 15, 20). HPV is then thought to escape into the cytoplasm and travel by an unknown, microtubule-dependent route to the nucleus where virus replication occurs (12, 19). One study concluded that HPV16 traffics through the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (11). The L2 protein appears to be important for proper intracellular trafficking, as does binding of sorting nexin 17 to an internal segment of L2 (21–23).

In all cells, newly synthesized proteins must be transported to their site of action, but the transport pathway that conveys cargo from the Golgi apparatus to the endosome and cell surface depletes Golgi factors required to maintain the flow of traffic. Therefore, cells use vesicular retrograde transport pathways to replenish the stores of these required trafficking factors. An important component of the retrograde pathway is the retromer, a multisubunit cytoplasmic machine that initiates vesicular transport of proteins from the endosome to the trans-Golgi network (TGN) to replenish factors depleted during anterograde trafficking (24–28). In many cases, the retromer engages substrates by binding to a segment of the cargo that protrudes into the cytoplasm from the lumen of the endosome (29–31). The retromer then recruits additional factors to induce the budding off of smaller vesicles, which are transported to the TGN in a microtubule-dependent fashion and fuse with the TGN membrane to deliver cargo. The retromer has not been previously implicated in productive infection by any virus.

Here, we conducted a genome-wide siRNA screen to identify cellular factors required for HPV16 infection of cultured epithelial cells. Our experiments revealed that HPV entry requires multiple cellular proteins acting in the endosome-to-Golgi retrograde transport pathway. Notably, the retromer is required for efficient HPV infection and trafficking of incoming virus to a Golgi-like compartment, and viral capsid proteins form a stable complex with the retromer during cell entry. Thus, the retromer constitutes a “missing link” in HPV entry, after endosome acidification but prior to arrival in the nucleus.

Results

Genome-Wide siRNA Screen for Human Genes Required for HPV16 Infection.

To identify cellular factors required for infection of epithelial cells by HPV16, we conducted a genome-wide siRNA screen in HeLa-S3 cervical carcinoma cells, which are highly susceptible to infection with HPV16 pseudovirions (PsVs). Because the carcinogenic process in these cells was initiated by infection with HPV18, they presumably retain much of the cellular machinery that mediates normal HPV entry.

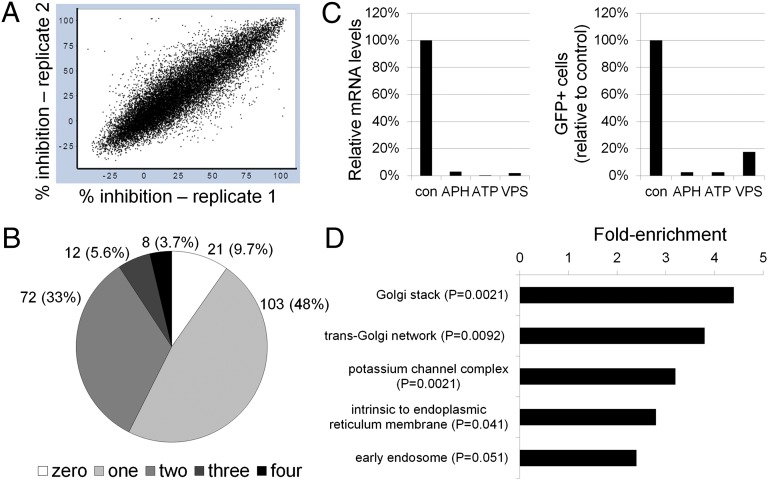

We designed a high-throughput cell-based assay to score the early phase of HPV infection with replication-deficient PsVs containing a reporter plasmid expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP) packaged in an L1 + L2 HPV16 capsid (HPV16-GFP) (32). For the screen, we used the Dharmacon SmartPool human siRNA library, consisting of 18,119 siRNA pools targeting almost all human genes. HeLa-S3 cells were reverse transfected with pools of four siRNAs targeting each gene for 48 h in 384-well plates, infected with HPV16-GFP for an additional 48 h, and then assayed for GFP fluorescence by using a high-content optical imaging system (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). Each plate contained GFP and RNA-induced silencing complex-free (RISC-free) siRNAs as positive and negative controls, respectively. For each well, the GFP intensity per cell was calculated, and an intensity threshold was set to identify infected cells. The final readout was the percent of GFP-positive cells per well. The complete screen was run in triplicate and achieved superior statistical metrics, namely an average Z′ factor of 0.71 and Pearson correlation coefficients between replicates of 0.8–0.9 (Fig. 1A). We selected hits based on a calculated score [the modified activity score (MAS1)] that incorporated percent inhibition of infection and cellular toxicity (as assessed by DNA staining) for each siRNA pool, where a higher score indicates more inhibition of infection with less toxicity. We defined the 1,000 siRNAs with the highest average MAS1 scores as primary hits in the screen (SI Appendix, Table S1). We also identified siRNAs that potentiated infection, which will be described separately.

Fig. 1.

Genome-wide RNA interference screen for human genes required for HPV16 infection. (A) Scatter plot showing percent inhibition of HPV16-GFP infection for two different replicates of the genome-wide screen. Each spot represents a single siRNA pool. (B) Pie chart of 216 hits tested for HPV16-GFP inhibition in the confirmation screen, showing the number (and percentage) of active siRNAs for each hit. (C) HeLa-S3 cells were transfected with a control RISC-free siRNA (con) or siRNAs against APH1A (a γ-secretase subunit), ATP6AP2 (a V-ATPase subunit), or VPS29 (a retromer subunit). (Left) Knock-down efficiency of the targeted mRNA was assayed by qRT-PCR 48 h after transfection, and mRNA levels in knock-down cells were normalized to the cognate mRNA in control cells. (Right) Knock-down cells were infected with HPV16-GFP, and GFP expression was assayed 2 d later by flow cytometry. The fraction of GFP positive cells was normalized to the fraction of GFP positive cells in cells transfected with control siRNA. The results of an experiment performed in triplicate are shown; similar results were obtained in multiple independent experiments. (D) DAVID software was used to classify the 1,000 highest-ranked primary hits according to cellular compartment, and fold-enrichment of each category in the hit list compared with the complete siRNA library was calculated. Only gene categories enriched by more than twofold are shown. qRT-PCR, quantitative reverse transcriptase-PCR.

The vast majority of genes whose knock-down inhibited infection were not previously linked to papillomavirus infection. However, some of the hits—furin, the γ-secretase complex, and the vacuolar ATPase complex (which causes endosome acidification)—were reported by others to be required for HPV infection or are consistent with our prior understanding of this process (17–20). The identification of these genes validated our screen design and suggested that our findings were relevant to HPV16 infection.

Confirmation and Validation of Primary Screen.

To assess the reliability of the screen, we rescreened individual siRNAs from 216 high-ranking siRNA pools (SI Appendix, Table S2). HPV16-GFP infection was reproducibly inhibited by two or more siRNAs for almost half of the primary hits tested, and less than 10% of the hits were not validated by any of the four siRNAs (Fig. 1B). The identification of multiple active siRNAs for many genes suggested that these hits represented genes required for efficient HPV16 infection and did not reflect off-target effects. We also tested the siRNAs from 100 of these 216 hits against a replication-defective recombinant adenovirus encoding GFP (Ad5-GFP). There was minimal correlation between siRNAs that inhibited HPV16 or adenovirus infection (SI Appendix, Table S2). Thus, inhibition of HPV16-GFP infection was not due to general anti-viral effects or anti-GFP effects.

To validate these results we obtained single siRNAs for a number of genes, transfected them into HeLa-S3 cells, and measured target gene knock-down. Messenger RNA levels of the examined genes were decreased by more than 20-fold (examples shown in Fig. 1C). We also infected the knock-down cells with HPV16-GFP and, after 48 h, assayed GFP expression by flow cytometry. These siRNAs strongly inhibited HPV infection (Fig. 1C), but did not inhibit adenovirus (SI Appendix, Table S2).

Retrograde Transport Is Required for HPV Infection.

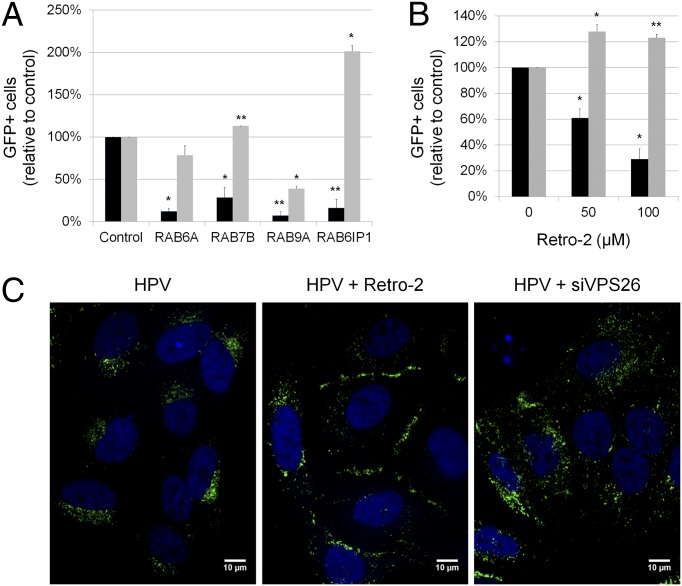

We used the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) to analyze all 1,000 primary hits to identify overrepresented gene categories. Classification of the hits by the gene ontology term “cellular compartment” showed that the top two enriched categories were Golgi stack and TGN (Fig. 1D). The enrichment of Golgi genes in our screen raised the possibility that HPV16 undergoes vesicular transport by the retrograde pathway from the endosome to the Golgi apparatus. Consistent with this hypothesis, the top 1,000 hits included VPS29 (Fig. 1C), a component of the retromer, which initiates retrograde transport of cargo from the endosome to the TGN, and a number of Rab GTPases and related proteins, including Rab6a, Rab6IP1, Rab7b, and Rab9 (SI Appendix, Table S1), which regulate retrograde movement of cellular cargo from the endosome to the TGN (33–35). We obtained individual siRNAs for these retrograde transport factors and confirmed that they repressed expression of their target mRNAs. As shown in Fig. 2A, siRNA-mediated knock-down of these genes reduced HPV16 infection efficiency by ∼70% or more but had relatively little effect on adenovirus infection. These genetic results strongly suggested that the retrograde pathway is important in HPV16 entry.

Fig. 2.

Retrograde transport is required for HPV infection. (A) Rab knock-down specifically inhibits HPV16-GFP infection. Effect of siRNAs on infection efficiency was assayed as described in the legend to Fig. 1C, Right. Black bars, HPV16-GFP infection; gray bars, Ad5-GFP infection. Results are the average (±SD) of multiple independent experiments. Statistical significance relative to cells transfected with control siRNA was determined by a paired two-tailed t test: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. (B) HeLa cells were infected with HPV16-GFP (black bars) or Ad5-GFP (gray bars) and treated with the indicated concentrations of Retro-2 at the time of infection. GFP expression was assayed by flow cytometry 40 h postinfection, and the fraction of GFP-positive cells was normalized to the fraction of GFP-positive cells in untreated sample. Results are displayed as described in A. (C) HeLa cells were transfected with RISC-free siRNA (Left and Center) or VPS26 siRNA (Right). Forty-eight hours later, cells were infected with HPV16-GFP at an MOI of 100. Cells in the Center panel were treated with 100 μM Retro-2 at the time of infection. Twenty hours postinfection, cells were immunostained with the polyclonal L1 antiserum and visualized by immunofluorescence microscopy. A single confocal slice is shown in each panel.

Retro-2 is a small molecule that inhibits retrograde transport of ricin toxin from the early endosome to the TGN (36). We tested here whether Retro-2 inhibited HPV16 infection. HeLa cells were pretreated with Retro-2 for 2 h, infected with HPV16-GFP or Ad5-GFP, and assayed by flow cytometry for GFP expression 2 d later. Adenovirus infection was not inhibited by Retro-2 treatment, but Retro-2 caused a dose-dependent inhibition of HPV16 infection (Fig. 2B), consistent with a role of retrograde transport in HPV infection. Retro-2 inhibited infection even if it was added several hours after HPV16-GFP addition (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). Localization of HPV components in the early endosome is readily apparent by 4 h after infection, when the Retro-2 is still effective. This timing suggests that Retro-2 acts at a postinternalization step.

We also performed confocal microscopy of HeLa cells infected with HPV16-GFP. Incoming virus was detected with a polyclonal antiserum that recognized the HPV16 L1 protein. By 20 h after infection, L1 was distributed throughout the cell, with concentration at discrete perinuclear sites (Fig. 2C). Treating HeLa cells with Retro-2 at the time of infection induced a dramatic relocalization of L1 to the cell periphery, demonstrating that retrograde transport was required for the perinuclear localization of L1, as well as for infectivity. Retro-2 treatment did not disrupt Golgi morphology (SI Appendix, Fig. S3).

HPV Traffics to a Golgi-Like Compartment.

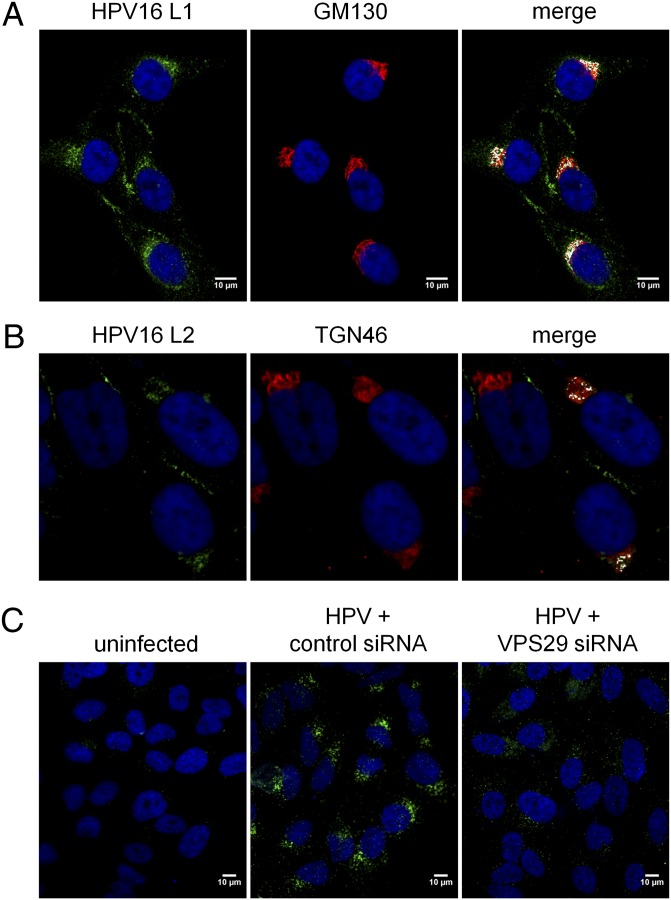

The evidence presented above indicated that retrograde transport is required for efficient HPV infection. To determine whether HPV16 itself traffics to the Golgi complex, we tested whether L1 colocalized with markers for Golgi and TGN compartments. By 16 h after infection, although most L1 staining was adjacent to the Golgi apparatus or the TGN, we also observed colocalization of L1 with the Golgi marker, GM130, and the TGN marker, TGN46, at discrete perinuclear sites “capping” the nucleus (white signals in Fig. 3A and SI Appendix, Fig. S4). Colocalization of L2 and TGN46 was also observed in infected cells (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

HPV localizes to a Golgi-like compartment. (A) HeLa cells were infected with HPV16-GFP for 16 h at an MOI of 50 and immunostained with polyclonal antiserum against L1 (green) and monoclonal antibody against GM130 (red). Areas of strongest overlap are pseudocolored white in the Right panel using an ImageJ colocalization plugin. The same confocal slice is shown in all three panels. (B) Samples were processed as in A except cells were stained with anti-L2 (RG1) and TGN46. (C) HeLa cells were transfected with a RISC-free siRNA (Left and Center) or VPS29 siRNA (Right). Forty-eight hours later, cells were mock-infected (Left) or infected with HPV16-GFP at an MOI of 100 (Center and Right). Sixteen hours postinfection, the cells were reacted with antibodies against L1 and GM130 and processed for PLA. A single confocal slice is shown in each panel.

To confirm transport of viral components to the Golgi, we used the proximity ligation assay (PLA), an immune-based method that generates a signal only when two proteins of interest are located within 40 nm of each other. HeLa cells were infected with HPV16-GFP for 15 h, stained with primary antibodies against L1 and GM130, and assayed by PLA. In cells infected with HPV16-GFP, but not in uninfected cells, many bright signals were observed with a discrete perinuclear localization (Fig. 3C, Center). Similar results were obtained when a different Golgi (golgin97) or a TGN (TGN46) antibody was used for PLA. This result indicated that at least some of the major capsid protein and Golgi markers are in close apposition in a perinuclear compartment. We designate the compartment containing HPV components and TGN/Golgi markers as the Golgi-like compartment (GLC). Taken together, these data demonstrated that components of the virus are transported by the retrograde pathway to the Golgi complex during entry.

Retromer Is Required for HPV16 Infection and Golgi Trafficking.

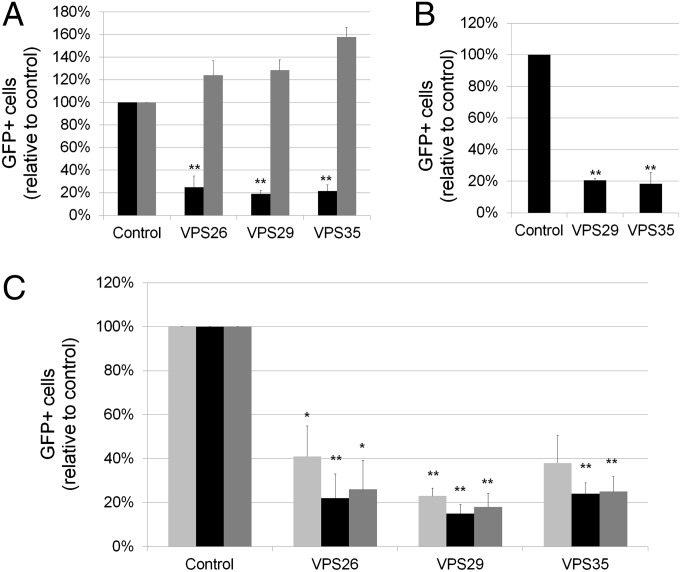

The cargo recognition core of the retromer is composed of three subunits: VPS26, VPS29, and VPS35. The VPS29 gene was a top hit in our screen with four positive siRNAs (SI Appendix, Table S2). To confirm that the retromer is required for HPV16 entry, we transfected HeLa cells with siRNAs against VPS26, VPS29, or VPS35, confirmed target gene knock-down, and infected the cells with HPV16-GFP or Ad5-GFP. HPV16 infection was strongly inhibited by multiple siRNAs to all three retromer subunits, but adenovirus infection was not inhibited (Fig. 4A). Retromer knock-down also inhibited HPV16-GFP infection of immortalized human cervical keratinocytes, a natural host cell for genital HPV infection (Fig. 4B). Efficient infection by HPV5 and HPV18 PsVs also depended on retromer function (Fig. 4C). Thus, the retromer is required for entry by multiple HPV types in various host cells. Notably, the retromer has not been previously implicated in virus entry.

Fig. 4.

The retromer is required for HPV infection. (A) HeLa-S3 cells were transfected with a RISC-free siRNA (control), or siRNAs against VPS26, VPS29, or VPS35. Knock-down cells were infected 48 h later with HPV16-GFP (black bars) or Ad5-GFP (gray bars). Infection efficiency was assayed as described in the legend to Fig. 1C, Right. Results are displayed as in Fig. 2A. (B) The ability of HPV16-GFP to infect human cervical keratinocytes was analyzed and displayed as in A. (C) HeLa cells were transfected with a RISC-free siRNA (control), or siRNAs against VPS26, VPS29, or VPS35. Knock-down cells were infected 48 h later with HPV16-GFP (black bars), HPV18-GFP (dark gray bars), or HPV5-GFP (light gray bars). Infection efficiency was assayed as described in the legend to Fig. 1C, Right. Results are displayed as in Fig. 2A.

As shown in Fig. 2C, Right, VPS26 knock-down caused L1 to lose its perinuclear localization and adopt a heterogeneous distribution, scattered over large areas within most cells, even though this treatment did not disrupt Golgi morphology (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). This phenotype is similar to the effects of retromer inactivation on cellular retromer cargoes (27). Exposure of hidden capsid epitopes or viral DNA was not affected by retromer knock-down, indicating that the retromer is not required for the initiation of capsid disassembly (SI Appendix, Fig. S5).

If the retromer is required for transport of HPV16 to the TGN, then knocking-down retromer function should impair localization of HPV components to the GLC. To examine this possibility, we infected control and VPS29 knock-down HeLa cells with HPV16 and, after 16 h, used PLA for L1 and GM130 to assess GLC localization. There was a dramatic reduction in both the number and intensity of PLA signals in VPS29 knock-down cells compared with control cells (Fig. 3C). Confocal image analysis with the Blobfinder software (Center for Image Analysis, Uppsala University) showed a fivefold reduction in the total fluorescence intensity of PLA signals in VPS29 knock-down cells. Thus, the retromer is required for trafficking of HPV16 to a GLC.

HPV16 Proteins Are Present in a Physical Complex with the Retromer.

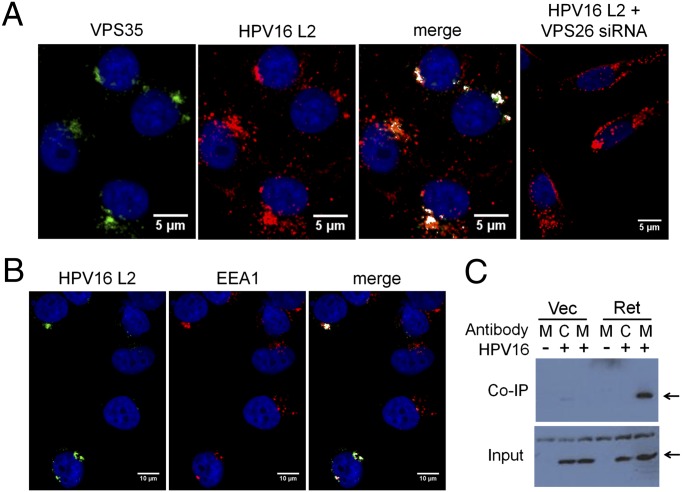

To test whether retromer components associated with incoming virions at the endosome, HeLa cells were transfected with a control or VPS26 siRNA and 48 h later infected with HPV16.L2HA-GFP, which expresses HA-tagged L2. After 12 h, cells were immunostained with antibodies against VPS35 and HA and examined by confocal microscopy. As shown in Fig. 5A, there was striking colocalization between VPS35 and L2 in infected cells, suggesting that there may be a physical association between the retromer and L2 in partially disassembled capsids. As expected, VPS35 expression and colocalization were abolished by VPS26 knockdown, which destabilizes all three retromer subunits (35) (Fig. 5A, Right). L2 and retromer also colocalized with the early endosomal marker EEA1 (Fig. 5B), suggesting that some L2 in capsids undergoing disassembly was in the vicinity of the retromer in the early endosome, consistent with the known role of retromer in initiating endosome-to-TGN trafficking.

Fig. 5.

The retromer forms a complex with incoming HPV16 capsids. (A) HeLa-sen2 cells were transfected with RISC-free siRNA (Left three panels) or VPS26 siRNA (Right). After 48 h, cells were infected with HPV16-GFP.L2-HA at an MOI of 200. Twelve hours postinfection, cells were immunostained with antibodies recognizing HA (red) or VPS35 (green). Areas of strongest overlap are pseudocolored white in the two Right panels by using an ImageJ colocalization plug-in. The same confocal slice is shown in the Left three panels. A single confocal slice is shown in the Right panel. (B) HeLa-sen2 cells were infected with HPV16-GFP L2-HA at an MOI of 200. Twelve hours postinfection, cells were immunostained with antibodies recognizing HA (green, HPV16 L2) or EEA1 (red). Areas of strongest overlap are pseudocolored white in the Right panel as in A. The same confocal slice is shown in all three panels. (C) 293T cells were transfected with genes encoding myc-tagged retromer subunits VPS26, VPS29, and VPS35 (Ret) or with an empty vector (Vec). As indicated, cells were then mock-infected (−) or infected with HPV16-GFP.L2-HA at an MOI of 50 for 8 h (+). Cells were then harvested in Nonidet P-40 buffer and precipitated with a myc (M) or an isotype- and species-matched control (C) antibody. Samples were analyzed by SDS/PAGE and immunoblotting with an HA antibody. Arrows indicate HA-tagged L2. Upper shows immunoprecipitated material; Lower shows 5% of total extract.

We next used coimmunoprecipitation to determine whether the retromer was present in a physical complex with incoming HPV16 capsids. We were not able to detect complex formation between endogenous retromer subunits and HPV components. Therefore, we analyzed cells expressing all three retromer subunits exogenously, which is a common approach to detect association between the retromer and its cargoes (31, 37). We transfected genes encoding myc-tagged VPS26, VPS29, and VPS35 into 293T cells. Thirty hours later, the cells were infected with HPV16.L2HA-GFP at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 50 for 8 h, lysed in detergent, and precipitated with an antibody against the myc tag. Complexes were analyzed by SDS/PAGE and Western blotting with an antibody against the HA epitope on L2. Strikingly, L2 protein was coimmunoprecipitated from extracts of infected cells expressing the myc-tagged retromer trimer, but not from infected cells transfected with an empty vector or from uninfected cells (Fig. 5C). An isotype-matched control antibody did not coprecipitate L2. The L1 protein also specifically coimmunoprecipitated with the retromer (SI Appendix, Fig. S6A). In contrast, when transfected cells were infected with SV40, we observed no specific coprecipitation of retromer and the SV40 major capsid protein, VP1 (SI Appendix, Fig. S6B). These experiments indicated that HPV16 capsid components are in a physical complex with the retromer during entry.

Discussion

In this report, we conducted a genome-wide siRNA screen to identify cellular proteins required for entry of HPV16-GFP pseudovirus into cervical carcinoma cells. Our experiments showed that HPV entry was strongly inhibited by siRNAs targeting several retrograde transport factors, including all three subunits of the retromer recognition core. Similar results were obtained in human cervical keratinocytes and for different HPV types, demonstrating that the retromer is required for entry by a variety of papillomaviruses into their normal host cells. Because the retromer has not been previously implicated in virus entry, our results show that HPV uses a previously undescribed mechanism of cell entry. Furthermore, retromer knock-down inhibited trafficking of HPV to a Golgi-like compartment, and incoming HPV16 is present in a physical complex with exogenously expressed retromer. Taken together, these results implied that HPV16 itself (or an infectious component of the virus) is transported by the retromer and retrograde machinery to the Golgi. The tools and approaches used here may reveal that other viruses also use this trafficking pathway. After this work was completed, another laboratory also implicated the TGN in HPV16 entry (38).

HPV undergoes a number of binding events, conformational changes, and proteolytic cleavage during entry, but the exact sequence of these steps and the mechanism of capsid disassembly and endosome escape are still matters of considerable controversy. Other laboratories showed that L1 dissociates from L2 during HPV entry and is sorted to the lysosome for degradation (39). We found that some L1, like L2, remains physically associated with the retromer and traffics to a Golgi-like compartment. It is possible that most molecules of L1 dissociate from L2, but that some L1 molecules persist in a remnant of the capsid responsible for productive infection. The PLA assay, which focuses on only those L1 molecules that arrive in the Golgi complex, may be more sensitive in this regard than standard immunostaining. Inhibition of retrograde transport typically reduced infection by about 80%, implying that retromer-mediated retrograde transport is the predominant but not necessarily the exclusive mode of intracellular trafficking for HPV16 in HeLa cells and cervical keratinocytes. Alternative entry pathways may assume increased importance in other cells, with other HPV types, or under certain infection conditions. For example, HPV31 infectious entry is independent of Rab7 in HaCaT cells, a skin keratinocyte cell line (20).

Taken together, our results support a model of HPV16 infection in which the retromer interacts with disassembling viral capsids at the endosome membrane. However, the retromer is in the cytoplasm whereas the incoming virus is initially in the lumen of the endosome. We speculate either that the virus “piggybacks” a ride with a cellular retromer cargo or adapter protein [such as sorting nexin 17 (22, 40)], which extends across the endosomal membrane, or that conformational changes in the capsid during disassembly in the endosome lumen expose a hydrophobic segment of L1 or L2, which can embed in the endosomal membrane and protrude into the cytoplasm where it can bind to the retromer. A transmembrane domain exists in the N terminus of L2 (41), and escape of HPV from the endosome and subsequent transport to the nucleus requires a hydrophobic C-terminal segment of the L2 protein, which can disrupt membranes and target proteins to membranes (21). It is possible that one or both of these segments span the endosomal membrane and engage the retromer. Our data suggest that the escape of HPV16 from the endosome involves retromer-mediated extraction of the virus into a vesicle, which is then routed to the TGN, rather than mechanical disruption of the endosomal membrane and transfer into the cytoplasm. However, L2 may mediate such a membrane-disrupting event after delivery to the TGN. Sequestration of infecting capsids within a vesicle may protect it from cytoplasmic anti-viral innate immune attack or ensure its delivery to other vesicular sites that contain cellular machinery required for subsequent disassembly or trafficking events. Presumably, analysis of additional hits from our screen will provide insight into entry events after TGN arrival. For example, the enrichment of ER factors in the hits from our screen (Fig. 1D) suggests that the viral genome may traffic from the Golgi to the ER during entry. It was previously reported that HPV16 infection was inhibited by Brefeldin A, which affects several trafficking steps including ER entry and by knock-down of protein disulfide isomerases that are primarily localized in the ER (11, 42). The enrichment of potassium channels in our list of hits suggests that the channels themselves or ion fluxes play a role in infection.

In summary, we have demonstrated a direct role for the retromer and retrograde trafficking during infectious entry by HPV16. The hits we identified, as well as other factors required for retrograde transport, represent potential antiviral targets. Our results also suggest that HPV can be used to analyze cellular retrograde transport pathways and reveal unexpected complexity to retrograde trafficking in this system. For example, both retromer and Rab9 are required for efficient HPV16 infection yet are thought to act in parallel pathways during retrograde transport. Indeed, we have in essence conducted a genome-wide screen for retrograde transport factors because hits that interfere with HPV infection are candidates for such factors. Because perturbations of the retromer have been implicated in numerous diseases (43), further studies of HPV entry may have broad impact on our understanding of virology, basic cell biology, and disease pathophysiology.

Materials and Methods

Detailed experimental methods are presented in SI Appendix.

siRNA Screening.

HPV pseudovirus was generated in 293TT cells with p16-shell, expressing L1 and L2, and pCIneo-GFP, expressing GFP (32). Pseudovirus was titered by flow cytometry of infected HeLa-S3 cells for GFP fluorescence. The genome-wide screen was run in triplicate using the siGENOME SMARTpool collection (Dharmacon) consisting of 18,119 pools, each containing four different siRNAs targeting each transcript. Each plate contained RISC-free and GFP siRNA as negative and positive controls, respectively. siRNA was delivered by reverse transfection with RNAiMax (Invitrogen). After 48 h, HPV16-GFP was added at an MOI of 2, and cells were incubated for an additional 48 h. Cells were fixed in 4% (vol/vol) paraformaldehyde, and nuclei were stained with Hoescht dye 33342. All reagent addition and wash steps were carried out robotically. Images were acquired and analyzed using the Opera Confocal Imager (Perkin-Elmer) and the Acapella software package (Perkin-Elmer). Nuclear GFP intensities per cell were calculated, and an intensity threshold was used to determine the percentage of GFP-positive cells per well. To identify highly active but nontoxic siRNA pools, a modified activity score was used. Statistical analysis was carried out using ActivityBase (IDBS). The 1,000 siRNA pools with the highest scores were defined as primary hits and analyzed with the DAVID database. For the confirmation screen, unpooled siRNAs for 216 of the top hits were tested in duplicate as above.

Retro-2 Experiments.

HeLa cells were infected with HPV16-GFP or Ad5-GFP at an MOI of 0.5 and cotreated with Retro-2 (36). Two days after infection, fluorescence intensity was assayed by flow cytometry.

Proximity Ligation Assay.

HeLa cells on glass coverslips were infected with HPV16-GFP at an MOI of 100. Twelve to 16 h later, cells were fixed in 4% formaldehyde and stained with rabbit polyclonal antiserum against L1 (1:1,000) and mouse monoclonal antibody against GM130 (BD Transduction Laboratories) (1:250). PLA probes and reagents were used according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Olink Biosciences).

Retromer Immunoprecipitation.

The 293T cells were transfected with genes encoding myc-tagged VPS26, VPS29, and VPS35, or an empty vector (44). Thirty hours later, cells were infected with HPV16.L2HA-GFP at an MOI of 50 for 8 h and then lysed in buffer containing 1% Nonidet P-40. Extracts were immunoprecipitated with 1 μg of control or myc antibody (Millipore) and analyzed by immunoblotting.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Chris Buck, Jae Jung, Nam-Hyuk Cho, Richard Roden, Pat Day, and Martin Sapp for essential reagents; Lynn Cooley for use of her confocal microscope; Chris Burd for helpful discussions; and Jan Zulkeski for assistance in preparing the manuscript. A.L. was supported in part by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Predoctoral Training Grant T32 AI07019, A.P. was supported by a Leslie Warner Postdoctoral Fellowship from the Yale Cancer Center, and C.D.S.N. was supported by Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award F32 NS070687. The D.D. laboratory was supported by National Cancer Institute Grant P01 CA016038 and a pilot grant from the Yale Center for Molecular Discovery. The W.J.A. laboratory was supported by NIH Grants R01 CA071878 and P01 NS065719 and by a Johnson & Johnson Translational Innovation Partnership Award.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

A preliminary version of this study, reporting the presence of HPV components in the Golgi/TGN, was presented at The DNA Tumour Virus Meeting, Montreal, July 2012.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1302164110/-/DCSupplemental.

See Commentary on page 7116.

References

- 1.Inoue T, Moore P, Tsai B. How viruses and toxins disassemble to enter host cells. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2011;65:287–305. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-090110-102855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chaturvedi AK, et al. Human papillomavirus and rising oropharyngeal cancer incidence in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(32):4294–4301. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.4596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parkin DM, Bray F. Chapter 2: The burden of HPV-related cancers. Vaccine. 2006;24(Suppl 3):S11–S25. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.05.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Modis Y, Trus BL, Harrison SC. Atomic model of the papillomavirus capsid. EMBO J. 2002;21(18):4754–4762. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giroglou T, Florin L, Schäfer F, Streeck RE, Sapp M. Human papillomavirus infection requires cell surface heparan sulfate. J Virol. 2001;75(3):1565–1570. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.3.1565-1570.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joyce JG, et al. The L1 major capsid protein of human papillomavirus type 11 recombinant virus-like particles interacts with heparin and cell-surface glycosaminoglycans on human keratinocytes. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(9):5810–5822. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.9.5810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Selinka HC, Giroglou T, Nowak T, Christensen ND, Sapp M. Further evidence that papillomavirus capsids exist in two distinct conformations. J Virol. 2003;77(24):12961–12967. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.24.12961-12967.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abban CY, Bradbury NA, Meneses PI. HPV16 and BPV1 infection can be blocked by the dynamin inhibitor dynasore. Am J Ther. 2008;15(4):304–311. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0b013e3181754134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Day PM, Gambhira R, Roden RB, Lowy DR, Schiller JT. Mechanisms of human papillomavirus type 16 neutralization by l2 cross-neutralizing and l1 type-specific antibodies. J Virol. 2008;82(9):4638–4646. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00143-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Day PM, Lowy DR, Schiller JT. Papillomaviruses infect cells via a clathrin-dependent pathway. Virology. 2003;307(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(02)00143-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laniosz V, Dabydeen SA, Havens MA, Meneses PI. Human papillomavirus type 16 infection of human keratinocytes requires clathrin and caveolin-1 and is brefeldin a sensitive. J Virol. 2009;83(16):8221–8232. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00576-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sapp M, Bienkowska-Haba M. Viral entry mechanisms: Human papillomavirus and a long journey from extracellular matrix to the nucleus. FEBS J. 2009;276(24):7206–7216. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07400.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schelhaas M, et al. Human papillomavirus type 16 entry: Retrograde cell surface transport along actin-rich protrusions. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4(9):e1000148. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schelhaas M, et al. Entry of human papillomavirus type 16 by actin-dependent, clathrin- and lipid raft-independent endocytosis. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8(4):e1002657. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schiller JT, Day PM, Kines RC. Current understanding of the mechanism of HPV infection. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;118(1) Suppl:S12–S17. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bienkowska-Haba M, Patel HD, Sapp M. Target cell cyclophilins facilitate human papillomavirus type 16 infection. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5(7):e1000524. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang HS, Buck CB, Lambert PF. Inhibition of gamma secretase blocks HPV infection. Virology. 2010;407(2):391–396. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karanam B, et al. Papillomavirus infection requires gamma secretase. J Virol. 2010;84(20):10661–10670. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01081-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Richards RM, Lowy DR, Schiller JT, Day PM. Cleavage of the papillomavirus minor capsid protein, L2, at a furin consensus site is necessary for infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(5):1522–1527. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508815103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith JL, Campos SK, Wandinger-Ness A, Ozbun MA. Caveolin-1-dependent infectious entry of human papillomavirus type 31 in human keratinocytes proceeds to the endosomal pathway for pH-dependent uncoating. J Virol. 2008;82(19):9505–9512. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01014-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kämper N, et al. A membrane-destabilizing peptide in capsid protein L2 is required for egress of papillomavirus genomes from endosomes. J Virol. 2006;80(2):759–768. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.2.759-768.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bergant Marušič M, Ozbun MA, Campos SK, Myers MP, Banks L. Human papillomavirus L2 facilitates viral escape from late endosomes via sorting nexin 17. Traffic. 2012;13(3):455–467. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2011.01320.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pereira R, Hitzeroth II, Rybicki EP. Insights into the role and function of L2, the minor capsid protein of papillomaviruses. Arch Virol. 2009;154(2):187–197. doi: 10.1007/s00705-009-0310-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Attar N, Cullen PJ. The retromer complex. Adv Enzyme Regul. 2010;50(1):216–236. doi: 10.1016/j.advenzreg.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bonifacino JS, Hierro A. Transport according to GARP: Receiving retrograde cargo at the trans-Golgi network. Trends Cell Biol. 2011;21(3):159–167. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burd CG. Physiology and pathology of endosome-to-Golgi retrograde sorting. Traffic. 2011;12(8):948–955. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2011.01188.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seaman MN. Cargo-selective endosomal sorting for retrieval to the Golgi requires retromer. J Cell Biol. 2004;165(1):111–122. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200312034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Strochlic TI, Schmiedekamp BC, Lee J, Katzmann DJ, Burd CG. Opposing activities of the Snx3-retromer complex and ESCRT proteins mediate regulated cargo sorting at a common endosome. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19(11):4694–4706. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-03-0296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nothwehr SF, Ha SA, Bruinsma P. Sorting of yeast membrane proteins into an endosome-to-Golgi pathway involves direct interaction of their cytosolic domains with Vps35p. J Cell Biol. 2000;151(2):297–310. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.2.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rojas R, et al. Regulation of retromer recruitment to endosomes by sequential action of Rab5 and Rab7. J Cell Biol. 2008;183(3):513–526. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200804048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tabuchi M, Yanatori I, Kawai Y, Kishi F. Retromer-mediated direct sorting is required for proper endosomal recycling of the mammalian iron transporter DMT1. J Cell Sci. 2010;123(Pt 5):756–766. doi: 10.1242/jcs.060574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buck CB, Pastrana DV, Lowy DR, Schiller JT. Generation of HPV pseudovirions using transfection and their use in neutralization assays. Methods Mol Med. 2005;119:445–462. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-982-6:445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu TT, Gomez TS, Sackey BK, Billadeau DD, Burd CG. Rab GTPase regulation of retromer-mediated cargo export during endosome maturation. Mol Biol Cell. 2012;23(13):2505–2515. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-11-0915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Progida C, et al. Rab7b controls trafficking from endosomes to the TGN. J Cell Sci. 2010;123(Pt 9):1480–1491. doi: 10.1242/jcs.051474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seaman MN, Harbour ME, Tattersall D, Read E, Bright N. Membrane recruitment of the cargo-selective retromer subcomplex is catalysed by the small GTPase Rab7 and inhibited by the Rab-GAP TBC1D5. J Cell Sci. 2009;122(Pt 14):2371–2382. doi: 10.1242/jcs.048686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stechmann B, et al. Inhibition of retrograde transport protects mice from lethal ricin challenge. Cell. 2010;141(2):231–242. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Feinstein TN, et al. Retromer terminates the generation of cAMP by internalized PTH receptors. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7(5):278–284. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Day PM, Thompson CD, Schowalter RM, Lowy DR, Schiller JT. Identification of a role for the trans-Golgi network in HPV16 pseudovirus infection. J Virol. 2013;87(7):3862–3870. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03222-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bienkowska-Haba M, Williams C, Kim SM, Garcea RL, Sapp M. Cyclophilins facilitate dissociation of the human papillomavirus type 16 capsid protein L1 from the L2/DNA complex following virus entry. J Virol. 2012;86(18):9875–9887. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00980-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yin W, et al. SNX17 regulates Notch pathway and pancreas development through the retromer-dependent recycling of Jag1. Cell Regen. 2012;1(4):1–10. doi: 10.1186/2045-9769-1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bronnimann MP, Chapman JA, Park CK, Campos SK. A transmembrane domain and GxxxG motifs within L2 are essential for papillomavirus infection. J Virol. 2013;87(1):464–473. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01539-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Campos SK, Chapman JA, Deymier MJ, Bronnimann MP, Ozbun MA. Opposing effects of bacitracin on human papillomavirus type 16 infection: Enhancement of binding and entry and inhibition of endosomal penetration. J Virol. 2012;86(8):4169–4181. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05493-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McGough IJ, Cullen PJ. Recent advances in retromer biology. Traffic. 2011;12(8):963–971. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2011.01201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kingston D, et al. Inhibition of retromer activity by herpesvirus saimiri tip leads to CD4 downregulation and efficient T cell transformation. J Virol. 2011;85(20):10627–10638. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00757-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.