Abstract

Cell polarization requires increased cellular energy and metabolic output, but how these energetic demands are met by polarizing cells is unclear. To address these issues, we investigated the roles of mitochondrial bioenergetics and autophagy during cell polarization of hepatocytes cultured in a collagen sandwich system. We found that as the hepatocytes begin to polarize, they use oxidative phosphorylation to raise their ATP levels, and this energy production is required for polarization. After the cells are polarized, the hepatocytes shift to become more dependent on glycolysis to produce ATP. Along with this central reliance on oxidative phosphorylation as the main source of ATP production in polarizing cultures, several other metabolic processes are reprogrammed during the time course of polarization. As the cells polarize, mitochondria elongate and mitochondrial membrane potential increases. In addition, lipid droplet abundance decreases over time. These findings suggest that polarizing cells are reliant on fatty acid oxidation, which is supported by pharmacologic inhibition of β-oxidation by etomoxir. Finally, autophagy is up-regulated during cell polarization, with inhibition of autophagy retarding cell polarization. Taken together, our results describe a metabolic shift involving a number of coordinated metabolic pathways that ultimately serve to increase energy production during cell polarization.

Keywords: energy metabolism, AMPK, mitochondrial fusion

A defining feature of metazoans is the existence of polarized cell layers or epithelium, which give rise to the 3D shapes of different body parts and types (1). The formation and maintenance of polarized epithelium is multifaceted, requiring specific cell–cell adhesion molecules, cytoskeletal factors, and intracellular trafficking components (2–4). These give rise to apical and basolateral membrane surface domains that permit directional absorption and secretion of proteins and other solutes. The ability of cells to polarize and maintain their polarity is energy-dependent (5); surprisingly, however, it is under conditions of low energy, including under nutrient starvation and stress, that cells most often initiate polarization (5). For example, cell populations grown in tissue culture usually require nutrient deprivation to initiate polarization into an epithelium. Likewise, single amoeboid Dictyostellum cells transition to a highly polarized, multicellular form (i.e., fruiting body) only when starved (6, 7). These observations suggest that low energy availability, such as occurs after acute cell stress, somehow acts to trigger a signaling cascade that boosts the energy production required for cell polarization.

During nutrient depletion and stress conditions, the master cellular metabolic sensor, AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), is activated (5, 8). AMPK inhibits ATP-consuming pathways that are not crucial for survival (e.g., mammalian target of rapamycin) and stimulates catabolic processes, including autophagy, which degrades cellular components through fusion of autophagosomes to generate nutrients (5, 9). The amino acids, lipids, and cellular components derived from autophagy provide fuel for starved/stressed cells (9–11). AMPK activation also turns on transcriptional pathways for mitochondrial gene expression (5, 12, 13). This enhances mitochondrial catabolic activities (including fatty acid β-oxidation, which provides fuel for driving the tricarboxylate acid cycle) and also increases mitochondrial bioenergetics, whose respiratory oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) mechanism is more efficient in generating cellular ATP compared with glycolysis (14, 15). Thus, by switching on pathways that can mobilize energy and cause cell growth, AMPK allows cells to overcome nutrient deprivation and stress conditions (16).

AMPK becomes active during cell polarization (17–19), and its activity is required for this process (17). Indeed, AMPK activators accelerate polarization, whereas AMPK inhibition (by overexpression of a dominant-negative form) blocks polarization (17, 18). Suggested roles of AMPK during polarization include helping switch on ATP-requiring components of conserved polarization machinery, including tight junctions (18, 20), recycling endosomes (4), and dynamic microtubules (21); however, AMPK also may function to activate signaling networks to boost ATP and nutrient levels (13). With this second function in mind, we explored the roles of mitochondria and autophagy during cell polarization, testing whether changes in their activity are necessary for cells to mobilize metabolic resources to meet the increased energy demands of polarization. Our results show that this is indeed the case, with polarizing cells initiating a regulatory cascade that switches on pathways leading to increased mitochondrial bioenergetics and autophagy.

Results

ATP Levels Increase Progressively in Parallel with Hepatocyte Polarization.

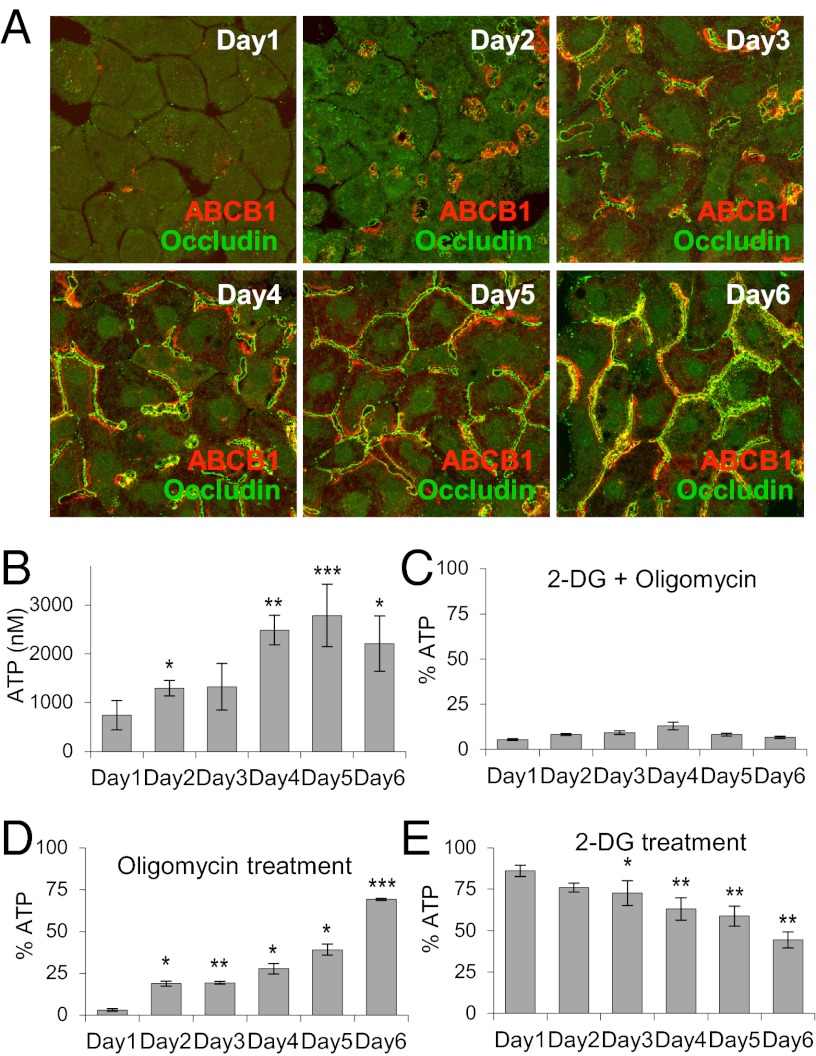

Polarized hepatocytes have apical and basolateral membranes separated by tight junctions. The apical membranes of adjacent hepatocytes form the bile canaliculus, the smallest branch of the biliary system into which bile acids and other substances are secreted (22). Hepatocytes isolated from liver have been shown to repolarize and generate bile canaliculi when cultured in a collagen sandwich system (17). We used such a system to investigate potential roles of mitochondrial bioenergetics and autophagy during cell polarization. We began by monitoring the time course of hepatocyte polarization (i.e., the appearance of bile canaliculi) in the sandwich culture system over a 6-d period. Immunofluorescence analysis of apical protein ATP-binding cassette B1 (ABCB1) and tight junctional protein occludin in day 1 cultures revealed few canaliculi and showed that the cells were not polarized. In day 2 cultures, canaliculi increased in number and appeared small and round. In day 3 and 4 cultures, canaliculi became more elongated and interconnected, indicative of a polarizing system. By day 5–6, canaliculi formed a network resembling the fully polarized morphology observed in intact liver (Fig. 1A). The cells maintained this functional organization for approximately 2 wk. Throughout this period, the cells remained nondividing, similar to polarizing hepatocytes observed in vivo. These results indicate that hepatocytes transform from nonpolarized to fully polarized within 4–5 d of culturing.

Fig. 1.

ATP levels and OXPHOS during hepatocyte polarization. (A) Immunofluorescence analysis of occludin (green) and ABCB1 (red) are performed to study canalicular structure. Merged projection images are from Z-serials of confocal images. (B) ATP levels in day 1–6 cells. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 compared with day 1. (C) Percentage of ATP in cells treated with 100 mM 2-DG and 10 μg/mL oligomycin for 4 h. (D) Percentage of ATP in day 1–6 cells treated with 10 μg/mL oligomycin for 4 h. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 compared with day 1. (E) Percentage of ATP in day 1–6 cells treated with 100 mM 2-DG for 4 h. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 compared with day 1. In C, D, and E, ATP levels were normalized to respective controls at each time points. Data are from three individual experiments.

We next monitored ATP levels during polarization. ATP levels within cells are normally maintained in the low millimolar range owing to cellular mechanisms that balance energy-consuming and -producing processes (8). Once hepatocytes were isolated after collagenase perfusion and plated in collagen sandwich cultures, ATP levels plummeted, possibly due to release of ATP by membrane damage. At day 1, cultures still had very low ATP levels (Fig. 1B, day 1). ATP levels began to rise by day 2, and reached maximal levels by day 4–6, when cells had polarized (Fig. 1B, days 2–6). These results indicate that cellular ATP levels are initially low when cells are nonpolarized and increase progressively in parallel with polarization. Thus, cells undergoing polarization have mechanisms for boosting their energy production.

Polarizing Hepatocytes Use OXPHOS Rather than Glycolysis as a Primary Energy Source.

Cells use two principle sources of cellular ATP production: glycolysis and OXPHOS (23). To examine which source is used during polarization, we measured ATP levels after treating day 1–6 cultures with oligomycin, an inhibitor of mitochondrial ATP synthase, to block OXPHOS and/or with 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG), an inhibitor of glycolysis. When cultures were treated with a combination of 10 μg/mL oligomycin and 100 mM 2-DG for 4 h on different days, ATP levels decreased to <10% of normal (Fig. 1C), indicating that energy production required glycolysis and/or OXPHOS. We next added oligomycin alone for 4 h, to test what fraction of the energy produced at different days was from OXPHOS. Of note, >90% of the ATP produced by day 1 cultures was sensitive to oligomycin (Fig. 1D), indicating that nonpolarized cells use OXPHOS as their primary energy source on day 1. On days 2–3, when cells first began to polarize, up to 80% of ATP production was still sensitive to oligomycin. Once cells became fully polarized by day 5–6, less of the ATP that they produced was oligomycin-sensitive (declining from 72% at day 4 to 30% at day 6) (Fig. 1D).

A reverse scenario was observed in treatment with 100 mM 2-DG alone for 4 h. In day 1 cultures, only ∼10% of the ATP produced was sensitive to 2-DG. This increased to ∼25% in day 2–3 cultures and continued to increase progressively thereafter, reaching >55% in day 6 cultures (Fig. 1E). These results suggest that during early stages of polarization, cells rely principally on OXPHOS to boost ATP to normal levels, and that once cells are fully polarized, they shift to a more glycolytic mode of energy metabolism with less reliance on OXPHOS.

Energy Production by OXPHOS Is Essential for Polarization of Hepatocytes.

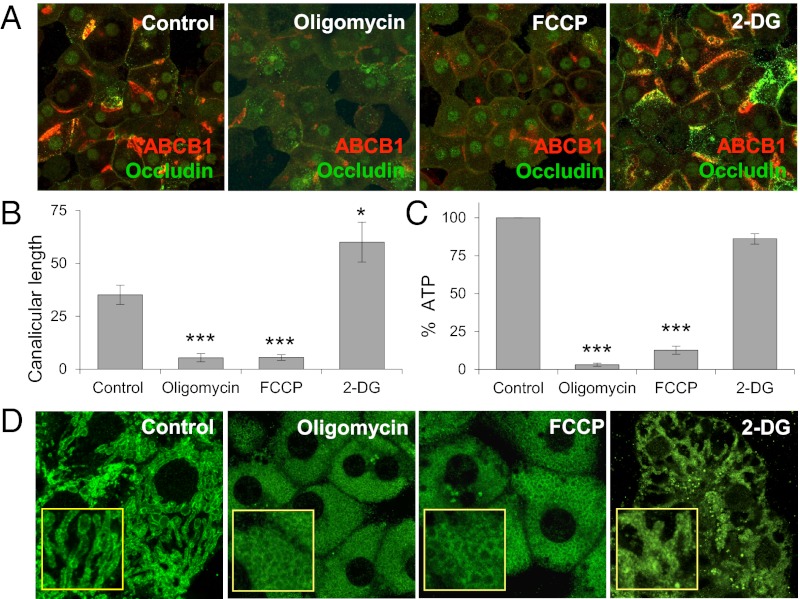

To determine whether the energy produced by OXPHOS is required for polarization of hepatocyte sandwich cultures, we treated day 1 cultures with oligomycin and evaluated cell polarization 24 h later. Oligomycin dramatically inhibited cell polarization (Fig. 2 A and B). Apical and tight junctional markers (i.e., ABCB1 and occludin) were dispersed, and canalicular length was significantly shorter compared with control cultures (Fig. 2 A and B). Similarly inhibited polarization was observed in cultures treated with Carbonyl cyanide 4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylhydrazone (FCCP), which uncouples OXPHOS by disrupting mitochondrial membrane potential (Fig. 2 A and B). This was observed when FCCP was added to either day 1 or day 2 cultures and monitored 24 h later (Fig. 2 A and B and Fig. S1). Both oligomycin and FCCP significantly decreased cellular ATP production (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Energy production by OXPHOS is essential for hepatocyte polarization. (A) Immunofluorescence analysis of occludin (green) and ABCB1 (red) in day 1 cells treated with 0.1 μg/mL oligomycin, 1,600 nM FCCP, or 100 mM 2-DG for 24 h. Merged projection images are from Z-serials of confocal images. (B) Canalicular lengths from three individual experiments. *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001 compared with control. (C) Percentage of ATP after treatment of day 1 cells with 10 μg/mL oligomycin, 1,600 nM FCCP, or 100 mM 2-DG for 4 h, normalized to control. ***P < 0.001 compared with control. Data are from three individual experiments. (D) Immunofluorescence analysis of mitochondrial outer membrane protein Tom20 in day 1 cells treated with 10 μg/mL oligomycin, 1,600 nM FCCP, or 100 mM 2-DG for 24 h. Insets show zoomed-in views.

In contrast to the effects of oligomycin and FCCP, treatment with 2-DG had the opposite effect, stimulating hepatocyte polarization, resulting in increased canalicular length compared with controls (Fig. 2 A and B). In these experiments, 2-DG was added to cultures on day 1, and the effects on polarization were evaluated 24 h later. Little change in total ATP production was seen, in contrast to the effects of oligomycin or FCCP (Fig. 2C). These results suggest that hepatocytes preferentially use OXPHOS over glycolysis to meet their ATP needs during polarization. Moreover, unless hepatocytes can make this glyoxylate shift (i.e., switch to OXPHOS), they do not polarize.

Examination of mitochondrial morphology in day 2 cultures revealed that mitochondria were highly tubulated in control or 2-DG treatment conditions, but highly fragmented under oligomycin or FCCP treatment (Fig. 2D). Because increased aerobic respiration correlates with mitochondrial fusion (24, 25), these results suggest that mitochondrial morphology might play a role in the cellular glyoxylate shift during polarization.

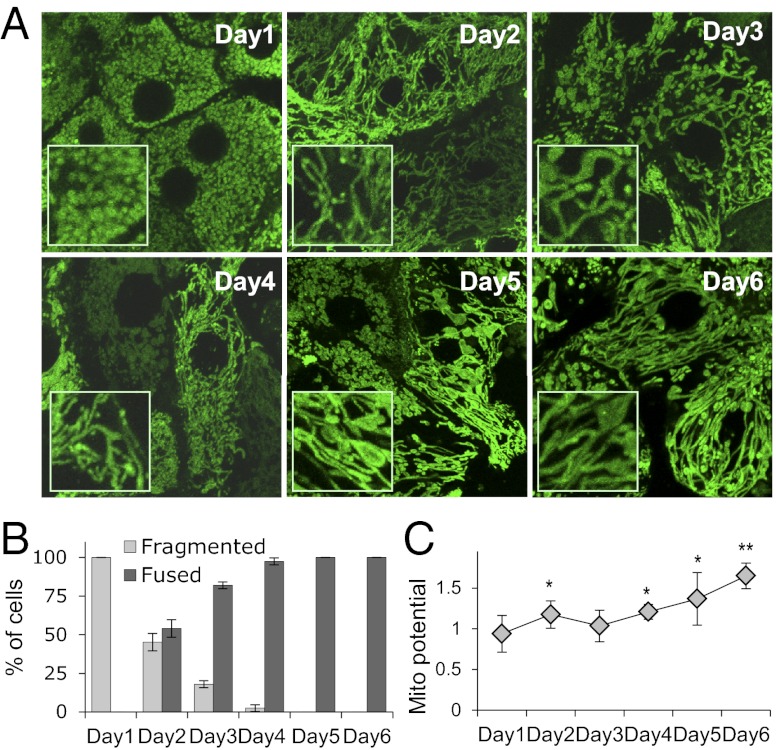

Mitochondria Fuse and Membrane Potential Increases During Polarization.

To address whether changes in mitochondrial shape accompany cell polarization, we sequentially examined mitochondrial morphology. The markers used for visualizing mitochondria included MitoTracker Green (Invitrogen), a green fluorescent dye that stains mitochondrial inner membranes (26), and antibodies to translocase of outer mitochondrial membranes 20 kDa (Tom20), a component of the outer mitochondrial membrane (27). In day 1 cultures, mitochondria appeared as hundreds of small, roundish elements of similar size dispersed throughout the cytoplasm (Fig. 3 A and B and Fig. S2, day 1). Because small, highly dispersed mitochondrial elements are inefficient ATP generators (24, 25, 28), the fragmented appearance of mitochondria in day 1 cultures might explain the extremely low ATP levels in these cells (Fig. 1B). The highly fragmented mitochondrial pattern seen in day 1 cultures was changed dramatically by day 2, with mitochondria appearing highly tubular and fused. By day 2, roughly 54% of cells exhibited a highly fused tubular mitochondrial network, and this pattern increased progressively until virtually all cells had fused mitochondria with enlarged vacuolar elements after day 4 (Fig. 3 A and B and Fig. S2). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of cells obtained on different days confirmed these mitochondrial size and shape changes during cell polarization (Fig. S3).

Fig. 3.

Mitochondria fuse and mitochondrial membrane potential increases as hepatocytes polarize. (A) Confocal microscopy images of mitochondria stained with MitoTracker Green in day 1–6 cells. Insets show zoomed-in views. (B) Percentage of cells with different mitochondrial shapes in day 1–6 cells. (C) Mitochondrial potential in day 1–6 cells from three individual experiments. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 compared with day 1.

Highly fused mitochondria are more metabolically active, exhibiting increased membrane potential in addition to boosted OXPHOS (24, 29). To test whether the shift of mitochondria to a highly fused state in polarizing cultures correlates with increased membrane potential, we measured mitochondrial membrane potential in day 1–6 cultures. Cultures were coincubated with tetramethylrhodamine ethylamine (TMRE), a red fluorescent dye that enriches in mitochondrial inner membranes based on their membrane potential, and MitoTracker Green, which stains mitochondria regardless of their membrane potential. Comparing the ratio of TMRE to MitoTracker Green labeling in mitochondria allowed us to monitor changes in mitochondrial membrane potential, which increased in parallel with mitochondrial tubulation and hepatocyte polarization from day 1 to day 6 (Fig. 3C and Fig. S4). Thus, the glyoxylate shift observed during polarization is correlated with increased fusion and electrical coupling of mitochondrial membranes.

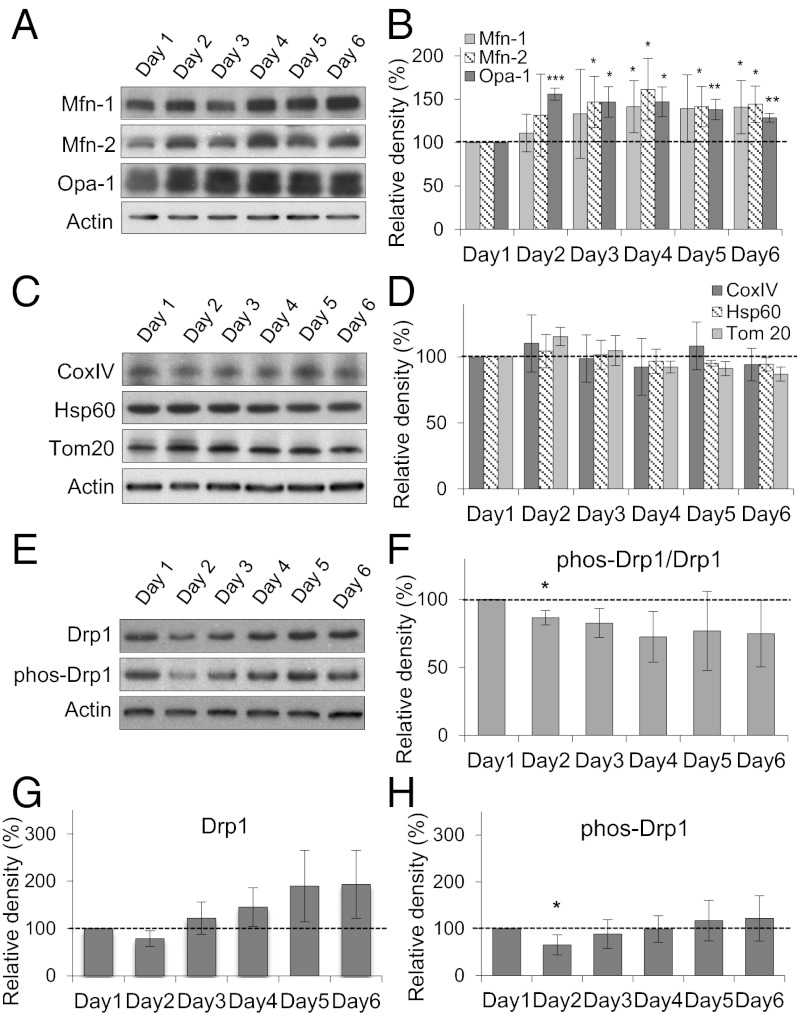

Mitochondrial Fusion Proteins Are Up-Regulated as Cells Polarize.

We next investigated possible mechanisms controlling the morphological change in mitochondria from fragmented to highly fused forms with polarization of hepatocytes. To do so, we performed Western blot analysis of proteins that regulate mitochondrial fusion and fission, including Optic atrophy 1 (Opa-1; associated with mitochondrial inner membranes) and mitofusin 1 and 2 (Mfn-1 and Mfn-2; associated with mitochondrial outer membranes), which control mitochondrial fusion, and dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1), which controls mitochondrial fission (14, 15, 30). Fusion proteins underwent up-regulation as cells polarized, with Opa-1 and Mfn-2 increasing by day 2–3 and Mfn-1 increasing by around day 4 (Fig. 4 A and B). Expression of mitochondrial structural proteins Tom20, Heat shock protein 60 (Hsp60), and Cytochrome c oxidase IV (CoxIV) were unchanged from day 1 to day 6 cultures (Fig. 4 C and D), indicating that the changes were specific.

Fig. 4.

Expression of mitochondrial fusion and fission proteins during hepatocyte polarization. (A) Expression of fusion proteins Mfn-1, Mfn-2, and Opa-1. (B) Densitometry analysis of the proteins in A. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 compared with day 1 cells. (C) Expression of mitochondrial structural proteins CoxIV, Tom20, and Hsp60. (D) Densitometry analysis of the proteins in C. (E) Expression of fission proteins Drp1 and phospho-Drp1 (ser 616). (F) Densitometry analysis of phospho-Drp1/Drp1. *P < 0.05. (G) Densitometry analysis of Drp1 only. (H) Densitometry analysis of phospho-Drp1 (ser 616) only. *P < 0.05. Data are from three individual experiments.

The mitochondrial fission protein Drp1 shows changes in expression level during cell polarization. Both Drp1 and its serine 616 phosphorylated form, which stimulates mitochondrial fission (15), were examined (Fig. 4 E–H). The ratio of the phosphorylated form to total Drp1 decreased on day 2 (Fig. 4F), corresponding to the time at which mitochondria first became highly fused (Fig. 3A). Because mitochondrial morphology is determined by a balance of fission/fusion events (28), these changes in fusion and fission protein levels, together with other factors, may favor a highly fused mitochondrial system during hepatocyte polarization.

AMPK Activity Is Not Correlated with Tubular Mitochondrial Morphology During Polarization.

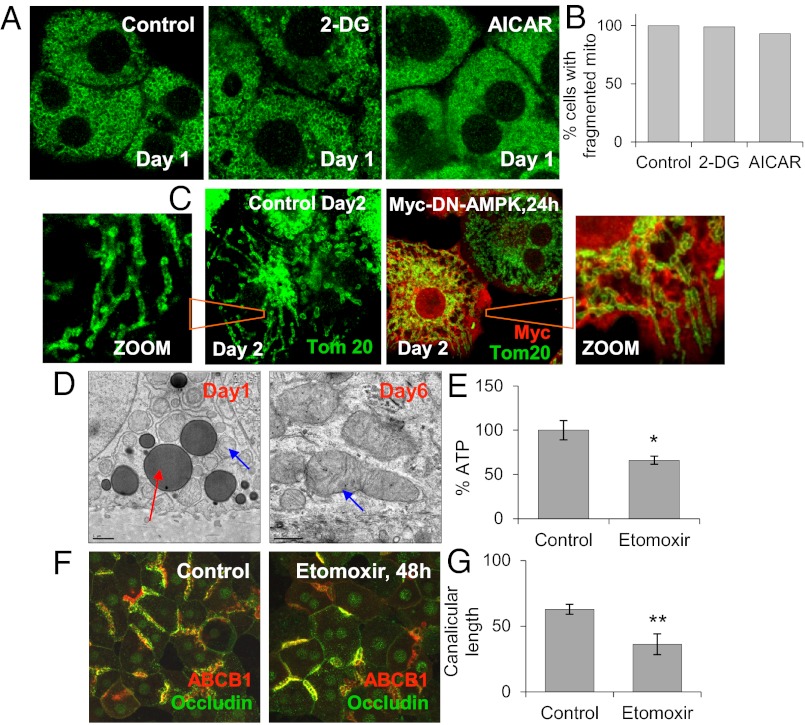

We investigated the relationship between AMPK activation and the mitochondrial fusion phenotype occurring in polarizing cells. The addition of 2-DG or 5-Aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide 1-β-D-ribofuranoside (AICAR) to day 0 or day 1 hepatocytes activated AMPK and accelerated polarization (Fig. S5 A–C) (17); however, mitochondria remained fragmented after day 0 in cells treated with 2-DG or AICAR (Fig. 5 A and B). Infection of day 1 cells with Myc-tagged dominant-negative AMPK (Myc-DN-AMPK) adenovirus aborted polarization, as reported previously (17); however, mitochondria were still fused and formed tubular structures in cells overexpressing Myc-DN-AMPK at 24, 48, and 72 h postinfection (Fig. 5C and Fig. S6 A and B). These results indicate that AMPK, which is required for polarization, may not participate in mitochondrial fusion despite its established role in mitochondrial biogenesis (5, 13).

Fig. 5.

AMPK activation is not correlated with mitochondrial fusion. (A) Immunofluorescence analysis of mitochondrial outer membrane protein Tom20 in day 0 cells treated with AMPK activator 100 mM 2-DG and 250 μM AICAR for 24 h. (B) Percentage of cells with fragmented mitochondria, normalized to control. (C) Immunofluorescence analysis for Tom20 (green) or Myc (red) in day 1 cells infected with Myc-DN-AMPK adenovirus, at 24 h postinfection. (D) TEM image of lipid droplets in day 1 and day 6 cells (red arrow, lipid droplets; blue arrow, mitochondria). (E) Percentage of ATP after treatment of day 1 cells with 100 μM etomoxir for 48 h. Data are from three individual experiments. *P < 0.05 compared with control. (F) Immunofluorescence of occludin (green) and ABCB1 (red) in day 1 cells treated with 100 μM etomoxir for 48 h. Merged projection images were from Z-serials of confocal images. (G) Canalicular lengths from three individual experiments. **P < 0.01 compared with control.

Lipid Droplets and β-Oxidation of Fatty Acids Play Roles in Polarization.

We next examined the nutrient source used by mitochondria to drive energy production during polarization. Hepatocytes depolarize after cell isolation, and thus many surface receptors and transporters, including glucose transporter type 4 (GLUT4), are likely internalized (4). Because these cells are unable to use external nutrients for ATP synthesis, the only alternative energy supply is from endogenous sources, such as lipid droplets. These cytoplasmic structures are composed of stored fatty acids, which can be used by mitochondria to drive OXPHOS through β-oxidation pathways (31). The idea that hepatocytes use lipid droplets as an energy source during polarization was suggested from TEM images showing their abundance in day 1 and day 2 cultures and disappearance thereafter (Fig. 5D).

We then examined whether lipid droplets are consumed by polarizing cells via β-oxidation pathways. Day 1 cultures were incubated with etoxomir, which inhibits β-oxidation (32), and cultures were examined 48 h later. Decreases in both ATP production and polarization were observed (Fig. 5 E–G). Thus, lipid droplet consumption and β-oxidation of fatty acids appear to be important in supplying substrates to mitochondria for OXPHOS as hepatocytes polarize.

Hepatocyte Polarization Requires Autophagy.

By itself, the boosted ATP production by OXPHOS is unlikely to be sufficient for cell polarization. This is because polarization also requires biosynthetic activities, including synthesis of lipids for generating polarized plasma membrane domains and production of specialized cytoskeletal and membrane trafficking components for regulated delivery of receptors and transporters (2, 3, 33). To accomplish these biosynthetic functions, polarizing cells need a source of amino acid, lipids, and carbohydrates. Autophagy recycles biosynthetic precursors through lysosomal degradation of sequestered cytoplasmic components (9, 34); thus, we tested whether autophagy provides the biosynthetic precursors required by polarizing cells.

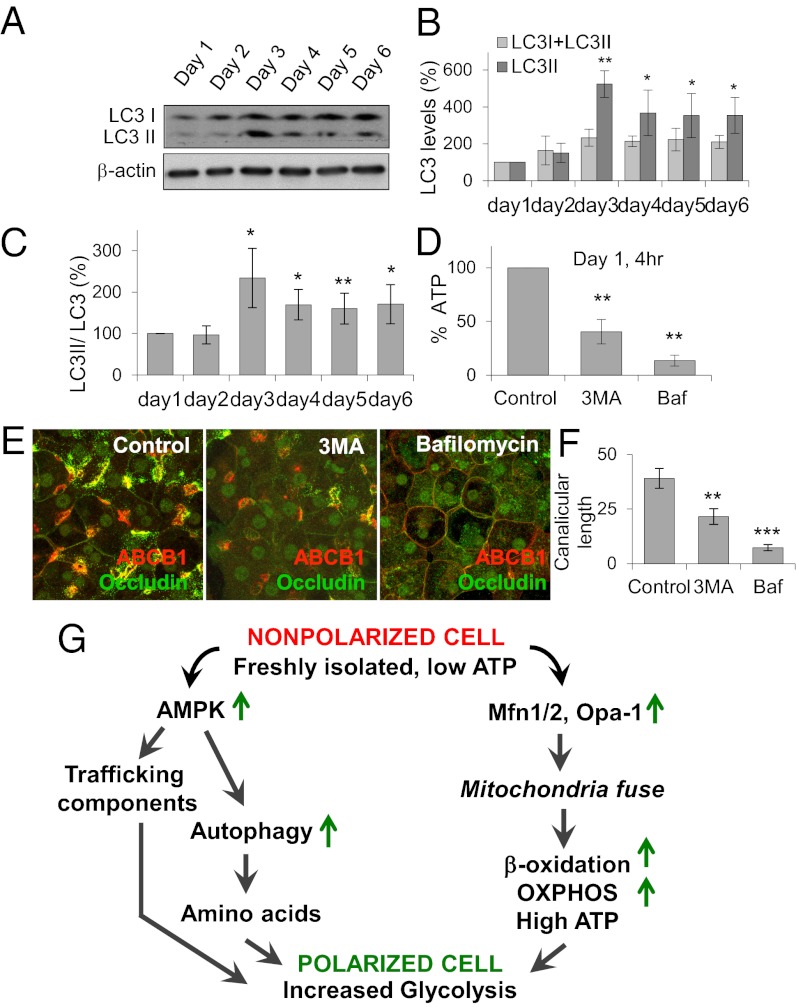

Autophagy was monitored in day 1–6 cultures by immunoblotting of cell lysates using antibodies to microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 (LC3), a canonical autophagic marker (35, 36). Association of LC3 with autophagosomal membranes coincides with its lipidation, which converts LC3 to a slightly lower molecular form, microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 II (LC3II). Total LC3 and LC3II levels were increased in day 2–6 cultures compared with day 1 cultures (Fig. 6 A–C), suggesting that autophagy is up-regulated during cell polarization. To determine whether autophagy is required for cell polarization, we tested the effect of inhibiting autophagy. We treated day 1 cells with either 3-methyladenine (3MA), which blocks autophagosome formation (37), or bafilomycin, which blocks fusion of autophagosomes to lysosomes (38) (Fig. S7). With both treatments, cellular ATP levels decreased by 60–80% (Fig. 6D), and hepatocyte polarization was inhibited (Fig. 6 E and F), indicating that autophagy is both up-regulated and necessary during polarization.

Fig. 6.

Hepatocyte polarization requires autophagy. (A) Expression of autophagy protein in day 1–6 cells. (B) Densitometry for total LC3 and LC3II. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 compared with day 1. (C) Densitometry for the ratio of LC3II to total LC3. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 compared with day 1. (D) Relative ATP levels in day 1 cells treated with 5 mM 3MA or 500 nM bafilomycin for 24 h. **P < 0.01 compared with control. (E) Immunofluorescence analysis of occludin (green) and ABCB1 (red) in day 1 cells treated with 5 mM 3MA or 500 nM bafilomycin for 24 h. Merged projection images are from Z-serials of confocal images. (F) Canalicular lengths. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 compared with control. Data are from three individual experiments. (G) Pathway for the contribution of mitochondrial OXPHOS and autophagy in hepatocyte polarization.

Discussion

The present study demonstrates that after isolation from liver, hepatocytes repolarize by shifting their metabolism to one involving coordinated elevation of mitochondrial OXPHOS and autophagy (Fig. 6G). This change in metabolism is similar to that occurring when cells are stressed or starved, but has the consequence of inducing polarization in the 3D collagen culture system. Our findings provide clues to explaining this similarity, offer an explanation for why polarizing cells require such a metabolic shift, and have implications for studies of liver disease, dysfunction, and regeneration.

Cells that are stressed/starved produce low levels of ATP, which leads to the activation of AMPK, the master cell energy sensor that shifts cellular metabolism to a more efficient pathway relying on mitochondrial ATP production (i.e., OXPHOS) and nutrients derived from autophagy. Freshly isolated hepatocytes have very low levels of ATP when first cultured, presumably owing to the stress of cell isolation, which causes cell depolarization and induces AMPK activation (17). Once activated, AMPK phosphorylates and activates key polarizing proteins, including tight junctional proteins and trafficking machinery, which are required for cell polarization (4, 18). However, AMPK activation also likely leads to another major effect: the boosting of cell energy and nutrient levels through NAD+-mediated downstream effects on mitochondria (13) and autophagy. Our findings support this energy-inducing role of AMPK during cell polarization. Soon after hepatocytes were cultured, their ATP levels rose in parallel with polarization, coinciding with AMPK activation (17). The rise in ATP was mediated almost entirely by OXPHOS, with little or no contribution from glycolysis. Indeed, the cells failed to polarize when OXPHOS was blocked with oligomycin, whereas they continued to polarize when glycolysis was blocked. This suggests that polarizing cells shift from glycolysis to OXPHOS to meet the energy demands of polarization, and that cells do not polarize unless this occurs.

This shift to OXPHOS in polarizing cells was correlated with mitochondria becoming highly fused with increased membrane potential, characteristics of highly energetic mitochondria. The importance of this change in mitochondrial morphology for energy production in polarizing hepatocytes is suggested by our finding that inhibition of mitochondrial function by FCCP or oligomycin decreased cellular ATP and impaired mitochondrial fusion. The change in mitochondria to a highly fused state occurred early during cell polarization (i.e., by day 2 in culture), concurrent with increased levels of mitochondrial fusion proteins Mfn-1/2 and Opa-1 and decreased activation of the fission protein Drp1 on day 2. Considering previous studies showing that Mfn-1 and Opa-1 are activated in stressed mouse embryonic fibroblasts (with highly fused mitochondria) (39), and that a cAMP-protein kinase A-Drp1 pathway is switched on in starved HeLa or mouse embryonic fibroblasts (which also have fused mitochondria) (40), it is possible that polarizing cells modulate their mitochondrial structure via similar pathways. AMPK activation did not correlate with mitochondria becoming fused in highly polarized cells. Further studies are needed to define the relation between AMPK activation and mitochondrial fusion and biogenesis.

Mitochondrial energy production during polarization was correlated with lipid droplet disappearance from cells, suggesting that fatty acids from lipid droplets are broken down by β-oxidation and then used by mitochondria as fuel. Inhibition of β-oxidation by etomoxir in day 1 cultures decreased cellular ATP and inhibited polarization, supporting a role of β-oxidation in mitochondrial ATP production and hepatocyte polarization.

Polarizing cells also require substrates for synthesizing new components essential for polarization, such as cadherin-catenin proteins involved in cell–cell adhesion and actin contractile bundles (41). Our findings that autophagy increases as cells polarize and that blocking autophagy inhibits polarization suggest that autophagy provides substrates for such biosynthesis. Increased autophagy in polarizing cells is likely triggered by AMPK activation (5). Autophagic degradation of mitochondria, known as mitophagy, is likely minimized in polarizing cells, given that highly tubular mitochondria are resistant to mitophagy (40, 42).

Our findings regarding the relative contributions of mitochondrial fusion, OXPHOS, lipid droplet consumption, β-oxidation, and autophagy to cell polarization have implications for treating liver disease and facilitating regeneration. Loss of cell polarity is likely a common denominator in liver failure associated with cancer, drug toxicity, alcoholism, and viral infections; thus, understanding how liver cells repolarize in response to these conditions could be of critical importance in directing research of these conditions. The roles of mitochondria and autophagy in repolarization make these processes of particular interest for developing drugs to block liver failure and for understanding how hepatocytes repair and restore normal morphology after infection and other stresses.

Although we have reported the changes in hepatocytes undergoing polarization, our findings are also likely relevant for other systems in which cells are polarized. A polarized epithelium is the first tissue formed during animal development, and body plans at all stages of development are constructed largely from epithelial tissues. We predict that the repair and regeneration of all of these epithelia require the metabolic shift involving mitochondria, lipid droplets, and autophagy described in this paper. Such a metabolic shift would reduce unnecessary energy-consuming processes (i.e., DNA replication) and also redirect energy use toward reorganizing cytoskeleton and membrane-bound transporters, tight junction assembly, and other polarization components for optimal uptake of nutrients and secretion of potential toxic products of cellular injury.

Materials and Methods

Reagents and Collagen Sandwich Culture of Rat Hepatocytes.

Reagents and the protocol for hepatocyte culture are described in SI Materials and Methods.

Immunofluorescence.

Details are provided in SI Materials and Methods.

Cellular ATP Measurement.

The protocol for cellular ATP measurement is specified in SI Materials and Methods.

Mitochondrial Staining and Mitochondrial Potential Assay.

Details are provided in SI Materials and Methods.

TEM.

The TEM procedure is described in detail in SI Materials and Methods.

Western Blot Analysis.

Western blot analysis was performed to measure protein expression. Details are provided in SI Materials and Methods.

Confocal Microscopy.

Confocal images were obtained with a Zeiss 710 confocal microscope and Zen 2010 program. Images were analyzed using ImageJ.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1304285110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Gibson WT, Gibson MC. Cell topology, geometry, and morphogenesis in proliferating epithelia. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2009;89:87–114. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(09)89004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bryant DM, Mostov KE. From cells to organs: Building polarized tissue. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9(11):887–901. doi: 10.1038/nrm2523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodriguez-Boulan E, Kreitzer G, Müsch A. Organization of vesicular trafficking in epithelia. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6(3):233–247. doi: 10.1038/nrm1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wakabayashi Y, Dutt P, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Arias IM. Rab11a and myosin Vb are required for bile canalicular formation in WIF-B9 cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(42):15087–15092. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503702102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hardie DG. AMP-activated protein kinase: An energy sensor that regulates all aspects of cell function. Genes Dev. 2011;25(18):1895–1908. doi: 10.1101/gad.17420111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weijer CJ. Dictyostelium morphogenesis. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2004;14(4):392–398. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsujioka M. Cell migration in multicellular environments. Dev Growth Differ. 2011;53(4):528–537. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2011.01268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hardie DG, Ross FA, Hawley SA. AMPK: A nutrient and energy sensor that maintains energy homeostasis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13(4):251–262. doi: 10.1038/nrm3311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mizushima N, Levine B. Autophagy in mammalian development and differentiation. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12(9):823–830. doi: 10.1038/ncb0910-823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang Z, Klionsky DJ. Eaten alive: A history of macroautophagy. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12(9):814–822. doi: 10.1038/ncb0910-814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mizushima N, Komatsu M. Autophagy: Renovation of cells and tissues. Cell. 2011;147(4):728–741. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Timmers S, et al. Calorie restriction-like effects of 30 days of resveratrol supplementation on energy metabolism and metabolic profile in obese humans. Cell Metab. 2011;14(5):612–622. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cantó C, et al. AMPK regulates energy expenditure by modulating NAD+ metabolism and SIRT1 activity. Nature. 2009;458(7241):1056–1060. doi: 10.1038/nature07813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nunnari J, Suomalainen A. Mitochondria: In sickness and in health. Cell. 2012;148(6):1145–1159. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Westermann B. Mitochondrial fusion and fission in cell life and death. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11(12):872–884. doi: 10.1038/nrm3013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mihaylova MM, Shaw RJ. The AMPK signalling pathway coordinates cell growth, autophagy and metabolism. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13(9):1016–1023. doi: 10.1038/ncb2329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fu D, Wakabayashi Y, Ido Y, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Arias IM. Regulation of bile canalicular network formation and maintenance by AMP-activated protein kinase and LKB1. J Cell Sci. 2010;123(Pt 19):3294–3302. doi: 10.1242/jcs.068098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zheng B, Cantley LC. Regulation of epithelial tight junction assembly and disassembly by AMP-activated protein kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(3):819–822. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610157104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fu D, Wakabayashi Y, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Arias IM. Bile acid stimulates hepatocyte polarization through a cAMP-Epac-MEK-LKB1-AMPK pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(4):1403–1408. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018376108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang L, Li J, Young LH, Caplan MJ. AMP-activated protein kinase regulates the assembly of epithelial tight junctions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(46):17272–17277. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608531103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakano A, et al. AMPK controls the speed of microtubule polymerization and directional cell migration through CLIP-170 phosphorylation. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12(6):583–590. doi: 10.1038/ncb2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kipp H, Arias IM. Trafficking of canalicular ABC transporters in hepatocytes. Annu Rev Physiol. 2002;64:595–608. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.64.081501.155793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Newmeyer DD, Ferguson-Miller S. Mitochondria: Releasing power for life and unleashing the machineries of death. Cell. 2003;112(4):481–490. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00116-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mitra K, Wunder C, Roysam B, Lin G, Lippincott-Schwartz J. A hyperfused mitochondrial state achieved at G1-S regulates cyclin E buildup and entry into S phase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(29):11960–11965. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904875106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Westermann B. Bioenergetic role of mitochondrial fusion and fission. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1817(10):1833–1838. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2012.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mitra K, Lippincott-Schwartz J. Analysis of mitochondrial dynamics and functions using imaging approaches. Curr Protoc Cell Biol. 2010;Chapter 4:Unit 4.25.1-21. doi: 10.1002/0471143030.cb0425s46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yano M, Terada K, Mori M. AIP is a mitochondrial import mediator that binds to both import receptor Tom20 and preproteins. J Cell Biol. 2003;163(1):45–56. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200305051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Otera H, Mihara K. Molecular mechanisms and physiologic functions of mitochondrial dynamics. J Biochem. 2011;149(3):241–251. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvr002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Song Z, Chen H, Fiket M, Alexander C, Chan DC. OPA1 processing controls mitochondrial fusion and is regulated by mRNA splicing, membrane potential, and Yme1L. J Cell Biol. 2007;178(5):749–755. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200704110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hyde BB, Twig G, Shirihai OS. Organellar vs cellular control of mitochondrial dynamics. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2010;21(6):575–581. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ducharme NA, Bickel PE. Lipid droplets in lipogenesis and lipolysis. Endocrinology. 2008;149(3):942–949. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spurway TD, Pogson CI, Sherratt HS, Agius L. Etomoxir, sodium 2-[6-(4-chlorophenoxy)hexyl] oxirane-2-carboxylate, inhibits triacylglycerol depletion in hepatocytes and lipolysis in adipocytes. FEBS Lett. 1997;404(1):111–114. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00103-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fu D, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Arias IM. Cellular mechanism of bile acid-accelerated hepatocyte polarity. Small GTPases. 2011;2(6):314–317. doi: 10.4161/sgtp.18087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zechner R, Madeo F. Cell biology: Another way to get rid of fat. Nature. 2009;458(7242):1118–1119. doi: 10.1038/4581118a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mizushima N, Yoshimori T. How to interpret LC3 immunoblotting. Autophagy. 2007;3(6):542–545. doi: 10.4161/auto.4600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barth S, Glick D, Macleod KF. Autophagy: Assays and artifacts. J Pathol. 2010;221(2):117–124. doi: 10.1002/path.2694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller S, et al. Shaping development of autophagy inhibitors with the structure of the lipid kinase Vps34. Science. 2010;327(5973):1638–1642. doi: 10.1126/science.1184429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shacka JJ, Klocke BJ, Roth KA. Autophagy, bafilomycin and cell death: The “a-B-cs” of plecomacrolide-induced neuroprotection. Autophagy. 2006;2(3):228–230. doi: 10.4161/auto.2703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tondera D, et al. SLP-2 is required for stress-induced mitochondrial hyperfusion. EMBO J. 2009;28(11):1589–1600. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gomes LC, Di Benedetto G, Scorrano L. During autophagy mitochondria elongate, are spared from degradation and sustain cell viability. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13(5):589–598. doi: 10.1038/ncb2220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yamada S, Pokutta S, Drees F, Weis WI, Nelson WJ. Deconstructing the cadherin-catenin-actin complex. Cell. 2005;123(5):889–901. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rambold AS, Kostelecky B, Elia N, Lippincott-Schwartz J. Tubular network formation protects mitochondria from autophagosomal degradation during nutrient starvation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(25):10190–10195. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107402108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.