Abstract

Distraction osteogenesis (DO) has been established as a useful technique in the correction of skeletal anomalies of the long bones for several decades. However, the use of DO in the management of craniofacial deformities has been evolving over the past 20 years, with initial experience in the mandible, followed by the mid-face and subsequently, the cranium. This review aims to provide an overview of the current role of DO in the treatment of patients with craniofacial anomalies.

Keywords: Airway obstruction, craniofacial, distraction, mid-face, mandible

INTRODUCTION

Cranial distraction osteogenesis

In a major review, Swennen, et al.[1] described the experience of distraction osteogenesis (DO) in 96 patients with craniofacial syndromes in a review of the clinical literature. They were noted to have had cranial distraction or combined mid-face and cranial distraction, mainly in patients with Apert, Crouzon, Pfeiffer syndrome, and cleft lip and palate. The technique was carried out predominantly in younger patients with monobloc and Le Fort III osteotomies being the most common procedures. Children under the age of 4 years underwent monobloc distraction for respiratory obstruction and severe exophthalmos with the use of internal distractors in 86.5% of the cases.

Cranial DO has also been applied to various forms of craniosynostosis whether for single or multiple sutural involvement.[2,3] Wiberg, et al.[4] reported the use of posterior calvarial distraction in cases of multiple suture craniosynostosis to expand the cranial volume to treat raised intracranial pressure (ICP). In a case series of 10 syndromic craniosynostoses, a mean posterior advancement of 19.7 mm was achieved and all cases were successful in relieving raised ICP. Only minor complications were reported and consisted of minor dural tears and superficial activation arm infections. Potential advantages cited were reduced blood loss and lower morbidity by maintaining a dura-cranium connection thus reducing dead space. Ko, et al.[5] described the three-dimensional changes after fronto-facial monobloc DO in five syndromic patients. After distraction of the supraorbital ridge, it was advanced 15.3 mm, which resulted in an increase of 11% in cranial volume. More significantly, it was noted that the upper airway volume increased by 85% and globe protrusion was also reduced by 3.7 mm on average.

Komuro, et al.[6] described the treatment of four cases of sagittal synostosis with a combination of distraction and contraction techniques. Mean operating time was 227 minutes and mean blood loss was 277 ml suggesting that DO techniques had the advantage of shortening operating time and reducing the blood loss over total calvarial remodeling. The 1-year follow-up computed tomography (CT) scan also showed that there was complete bony regeneration at the osteotomy sites.

Other advantages of distraction include a reduction in surgical dissection and bone resorption. However, there are a few significant disadvantages compared with traditional cranial vault remodeling by fronto-orbital repositioning. It is usually not possible to achieve complex three-dimensional movements with unidirectional distractors and a second procedure is required for the removal of the distraction devices.

Currently the role of DO in cases of craniosynostosis that require cranial remodeling remains unclear without long-term and larger case series. However, there seems to be growing body of support for DO techniques when combining cranial distraction with mid-facial advancement. Posterior vault distraction is also gaining popularity for raised ICP and Chiari malformations due to the reduced morbidity of expansion compared with traditional techniques.[7]

Midfacial distraction osteogenesis

Cohen, et al. were first to describe mid-facial distraction.[8] Since then, there have been numerous reports of DO at this level. There has also been an exponential growth in the experience and technology related to this approach.

The main indication emerging for DO of the mid-face is in cases of syndromic craniosynostosis where the maxilla, nasal complex, and zygomatic body are hypoplastic and the orbits are shallow. These deformities lead to gross morphological distortions and functional problems that may include airway obstruction, exorbitism with corneal ulceration, and lid dislocation. There has been an increasing awareness of the incidence of upper airway obstruction and undiagnosed obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) in patients with syndromic craniosynostosis with the suggestion that up to 50% of these patients may have undiagnosed OSA.[9] An early mid-facial distraction may also facilitate earlier decannulation of tracheostomy tubes with a consequent improvement in the quality of life [Figure 1]. Other functional problems associated with raised ICP include papilloedema with the threat of reduced visual acuity and neurodevelopmental delay.

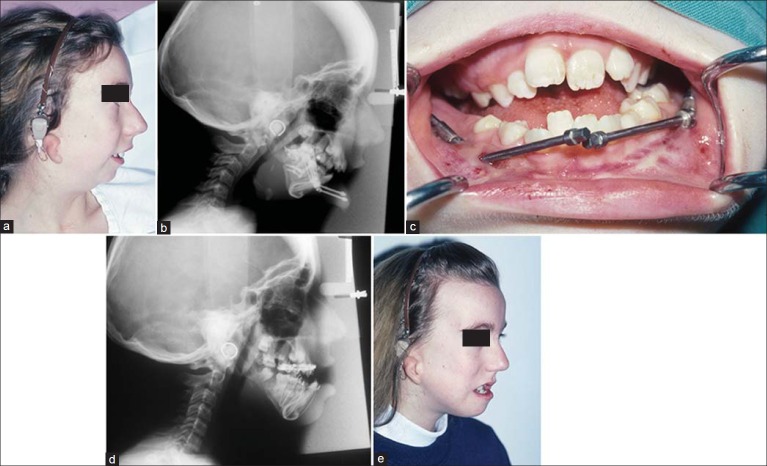

Figure 1.

Crouzon patient with upper airway obstruction for early Le Fort III distraction (a) Preoperative oblique facial view, (b) Post-distraction during consolidation phase, note both cheek and intranasal/pyriform fixation points for distraction and vector control

Patients with these anomalies usually have a major Class III skeletal malocclusion, often with a marked anterior open bite. The definitive correction of the malocclusion is delayed until skeletal maturity. However, the initial earlier correction of the mid-facial hypoplasia at the Le Fort III level has a major impact on facial aesthetics and reduces, and sometimes overcorrects, the occlusal deformity thus helping in the psychological development of the patient.[10] Hence, a monobloc distraction may be considered in the first 2 years of life in the presence of severe OSA and marked exophthalmos but, in our Institution, a Le Fort III distraction is undertaken at age 6-10 years when the facial skeleton is easier to mobilize with a reduced risk to the dentition and an attempt can be made to position the orbital margins at the ideal relationship to the globes.

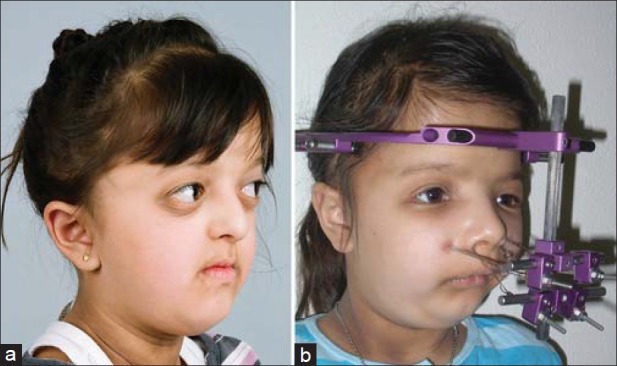

The advantages and disadvantages of DO to conventional mid-facial advancement procedures such as the monobloc or Le Fort III immediate repositioning have been reported extensively in the literature[11–15] with several reported advantages of DO. Larger advancements are possible with distraction as extensive bone grafting is not required and thus avoids secondary donor site morbidity[16] [Figure 2]. Holmes, et al. reported a mean advancement of 18 mm at the Le Fort III level[17] and there is the added advantage of gradual expansion of the soft tissue envelope (histiogenesis) that is also speculated to be the reason for lower rates of relapse in distracted cases.[18]

Figure 2.

Apert syndrome patient treated by internal Le Fort III distraction (Modular internal device) (a) Preoperative lateral facial view, (b) Postdistraction lateral cephalometric radiograph, (c) Postoperative lateral facial view

The use of distraction in monobloc segment advancement enables a reduction in frontal dead space that previously occurred with traditional repositioning as incremental advancement of the fronto-orbital complex allows sufficient time for dural expansion. Previously, the frontal/extradural dead space was noted to be persistent for up to 4 weeks postoperatively and therefore posed a risk of infection.[19] Distraction techniques have also been shown to reduce operating time and to reduce blood loss[6] and this, in turn, can translate into shorter hospital stays and reduced costs.

The disadvantages of distraction in the mid-facial region are similar to those elsewhere in the craniofacial skeleton. There is a need for a high degree of patient/family compliance to assist with device activation, a second procedure to remove the distractors is required and, in general, the treatment times are also longer. As mid-facial distraction involves a one-piece segment, it is not possible to perform separate level procedures such as a Le Fort I repositioning simultaneously.

Distractors for mid-facial advancement have been the focus of multiple designs and differing methods of applying forces. There are both internal and external appliances that provide the option to “push” or “pull” the mid-face, respectively. The external devices require a halo frame that is attached to the skull (e.g., rigid external distractor (RED) system, KLS Martin, Tuttlingen, Germany). Polley, et al. described the use of the RED device in a series of patients with severe mid-facial hypoplasia and demonstrated that a greater advancement of the mid-face was achieved than with conventional repositioning methods.[20]

The major advantage of external distraction is the ability to control and modify the vectors and forces during activation. In addition, the external devices are easier to apply and simpler to remove. The RED system is stabilized with cranial pin fixation and the wires fixed to the facial skeleton via a range of plates and techniques and are adjustable to permit multidirectional vectors. Intraoral splints have been used but newer innovations of internal fixation plates at the paranasal rims and infraorbital regions are also in use. The main disadvantage of the external halo device is its bulk that can result in physical and psychosocial discomfort for the patient.

Internal distractors are bone-borne and manufactured with customized or standardized plates that are extendable along a unidirectional track for distraction. Other internal distractors have been manufactured with resorbable plates that, following the distraction period, can be left in situ to dissolve after detachment of the activation arms. Cohen, et al. described the use of resorbable distractors in Le Fort III cases.[21] However, access for removal of the screws was still required. Burstein, et al. described a one stage resorbable system, that did not require secondary surgery.[22] This system was constructed from a combination polymer (Lactosorb – Walter Lorenz Surgical, Jacksonville, FL). However, resorbable systems are bulky by nature, and in order to provide sufficient strength, lack the malleability for close adaption to the bone surface. There have also been reports of foreign body granulomas of the covering skin.[22] Currently, there are no long-term follow-up studies on the use of internal resorbable distractors in the mid-face.

The bone-borne internal distractors have the advantage of being smaller in size with better patient acceptance and function independently of the upper dental arch as opposed to the early RED system that used cemented dental splints. The major disadvantage of this system is the need for a second procedure to remove the distractors. Moreover, unless customized, there is difficulty in setting the correct bilateral vectors to be parallel for symmetrical distraction. In addition, once the plates have been placed, it is not possible to modify the vectors.

Meling, et al. recently reported on 20 patients that were treated with mid-facial distraction where they compared 12 patients who had internal distraction and 8 patients with external distraction.[23] The patients underwent either a monobloc advancement or Le Fort III advancement and it was concluded that external devices required a shorter operating time but there was no significant difference in blood loss nor complications. However, it was noted that the external device provided better 3-dimensional control of the vectors.[21]

The long-term stability reports for metallic distractors have recently started appearing in the literature. Le Fort III distraction is now regarded as a relatively stable procedure. Nadjmi, et al. reported on 20 patients who underwent mid-facial distraction[24] with a follow-up period of 13-65 months. Using lateral cephalometric analyses to assess stability, they concluded that up to 5 years post-distraction, long-term stability was demonstrated.

Lee, et al. reported on the stability of a “dual method” mid-facial distraction in six patients with Crouzon syndrome.[25] They placed concurrent internal and external devices in the mid-face and following the distraction period, the consolidation period was 6 months. They evaluated the long-term stability with a mean follow-up of 4.5 years, and reported both stable facial contour changes and occlusal stability.

In a comprehensive follow-up study of 40 syndromic craniosynostosis patients who underwent a Le Fort III distraction with the RED device, 20 patients were followed for over 10 years post-distraction.[26] Follow-up CT scans demonstrated excellent ossification at the osteotomy sites. They concluded that with further growth of these patients, Class III malocclusions did not recur but mild exorbitism and mid-facial deficiency reappeared to some degree.

Hence, in the growing patient, mid-facial DO has become the procedure of choice in many units as a valuable and stable procedure, particularly in the management of children with airway problems and severe mid-facial retrusion. The greater amount of mid-facial advancement which can be achieved with gradual distraction has many advantages over traditional repositioning procedures.

MANDIBLE DISTRACTION OSTEOGENESIS

Craniofacial microsomia

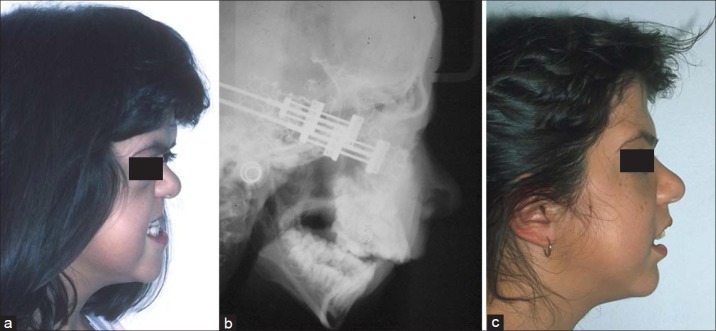

The role of DO in the management of hemifacial microsomia and associated conditions such as Goldenhar syndrome has been the subject of considerable controversy.[27] There is, as yet, no firm consensus on the role of distraction in these conditions. Protocols vary between units, with some centres confining distraction techniques to the milder forms of mandibular deformity whilst other seek to distract grossly hypoplastic structures.[28,29] However, there is an emerging consensus that there is little or no indication for the use of DO in patients with mild to moderate mandibular deformities (Type I or Type IIA Kaban modification of the Pruzansky classification).[30] In these patients, traditional orthognathic repositioning results is preferred unless airway obstruction is diagnosed at an earlier age requiring mandibular lengthening [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Bilateral craniofacial microsomia patient with upper airway obstruction treated successfully by internal mandibular distraction. (a) Preoperative lateral facial view, (b) Lateral cephalogram immediately following insertion of distractor, (c) Intraoral distractor in situ, (d) Lateral cephalogram post-distraction, (e) Postoperative lateral facial view

In the more severe mandibular deformities (Type IIB and III), the role of DO remains controversial. This is, in part, due to the discussion regarding whether hemifacial microsomia should be considered a progressive deformity or one that simply grows to scale. A progressive canting of the pyriform rims and occlusal plane was demonstrated by Kaban, et al.,[30] whereas Polley, et al. showed that in un-operated patients, the asymmetry did not progress and that the growth on the affected side matched the unaffected side.[31] However, it is our opinion that there is a spectrum between the two hypotheses. As facial growth continues in the postpubertal period, the complete absence of a condylar growth centre in severe cases will appear to progressively worsen with significantly less ability to match the normal side, whereas in cases with a mild hypoplastic condyle/ramus unit, the mandible will appear to grow more to scale.

The main objective of using DO in craniofacial microsomia patients has been to vertically lengthen the ramus with the intention of stretching the soft tissue envelope and thus overcome the propensity for relapse. In the absence of a well-developed condylar/ramus unit, the process of DO is of doubtful value as a definitive posterior stop for the proximal component is lacking, with a tendency for the fragment to be displaced posteriorly and superiorly.[32] For this reason, DO for the majority of craniofacial microsomia cases was abandoned by our Unit a decade ago, as the need for conventional techniques remain and the interim improvements appear not to be stable.

Recently, Meazzini, et al. reported on a long-term follow-up of 14 patients who were treated early with DO (mean age 5.9 years) compared with an untreated sample of 8 patients.[33] Both samples were followed up until the completion of growth. The results of this study showed that after the episode of DO, the vertical asymmetry was corrected with a ratio of the affected side to the unaffected side of 1:1. There was then a relapse of 16% in the first year noted and thereafter, there was a continued loss of the relative height of the ramus with a return toward the original ratio. This study highlighted that early DO intervention did not maintain the initial correction during growth.

In a critical review of literature to assess the effectiveness of DO in craniofacial microsomia patients, Mommaerts et al.[27] found that DO appeared to correct mandibular asymmetry for only a relatively short period of time and that there was no evidence that vertical height of the ramus was maintained. Hence, there is currently no definitive evidence that DO results in a more favorable outcome than the conventional treatment approach of reconstruction of the temporomandibular joint with autogenous costo-chondral bone grafting and adjunctive soft tissue augmentation techniques.

Distraction osteogenesis and traditional orthognathic surgery

Several studies have evaluated DO as a definitive mandibular advancement technique. Vos, et al. assessed mandibular stability after conventional bilateral sagittal split (BSSO) advancement and distraction techniques.[34] The mean advancement for both samples was 7 mm and there was no difference in the stability after 1 year of follow-up between the two techniques. Further follow-up at 4 years with the same sample of patients was reported by Baas, et al.,[35] who found no difference in stability between the techniques. Similar results were confirmed by Ow, et al.,[36] who demonstrated that advancements of between 6 and 10 mm resulted in no significant differences in stability after 1 year of follow-up.

With the enthusiasm of successful results using mid-facial and mandibular distraction, it has been asserted that the introduction of DO techniques would result in the elimination of traditional orthoganthic surgery.[37] However, this has not proved to be the case. In patients with syndromic craniosynostoses, DO can be applied at strategic times as part of a staged surgical treatment plan for the management of severe skeletal discrepancies. Distraction may be regarded as a useful additional technique to minimize skeletal deformities, but definitive orthognathic surgery remains the treatment of choice to enable accurate occlusal correction and good facial balance.

Distraction osteogenesis and management of upper airway obstruction

Infants and young children with syndromic craniosynostoses such as Crouzon and Apert syndromes often present with upper airway obstruction secondary to severe mid-facial deficiency where the retro-positioned complex restricts the dimension of the postnasal space and oropharynx. The high percentage of these patients with documented sleep studies indicating severe OSA suggests that this condition has been under-diagnosed and a cause of failure to thrive with the potential for the long-term sequelae of cor pulmonale and cardiac compromise.

Patients with micrognathia as a prominent feature, such as Pierre Robin Sequence, Treacher Collins syndrome, craniofacial microsomia, and Nager Syndrome, also often present with upper airway obstruction but this group has been recognized for many years with the diagnosis being evident in many during the neonatal period. Most paediatric units have employed a multi-disciplinary approach to the management of upper airway obstruction in these patients with team members including neonatologists, respiratory physicians, otolaryngologists, and craniomaxillofacial surgeons.

The methods of treating upper airway obstruction in the presence of micrognathia have included a range of nonsurgical and surgical techniques. Nonsurgical approaches commence with prone positioning and progress to nasopharyngeal intubation and continuous positive airway pressure with nasal tongs or a mask, if indicated. Long-term nasopharyngeal airways have also been advocated but with a notable failure rate and suboptimal oxygen saturation in a significant percentage.[38] Surgical methods have included glossopexy and tongue-lip adhesion[39] but when unsuccessful, tracheostomy has traditionally been the gold standard. However, tracheostomy can result in significant morbidity and mortality associated with the procedure.[40] Wetmore, et al. reviewed 450 cases of pediatric tracheostomies and noted a 19% complication rate in the first week after the tracheostomy, a 58% late complication rate, and a 0.5% mortality rate.[41] When used as the definitive management for upper airway obstruction, tracheostomy is a long-term requirement for at least 1-2 years and has a significant social impact on family life. In addition, this critical period for speech and language development is compromised.[42]

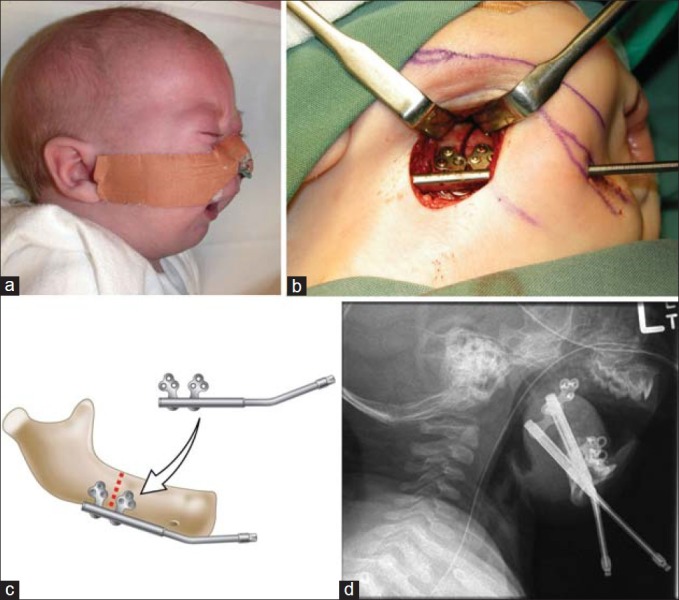

Over the past decade, mandibular distraction has been adopted as an additional modality in resolving upper airway obstruction due to micrognathia and has been a valuable substitute for tracheostomy in many cases, particularly in Pierre Robin Sequence. The use of mandibular distraction in neonates and infants with upper airway obstruction has been documented in a number of studies using both external and internal devices.[43–45] In our institution, infants with severe upper airway obstruction are initially managed by nasopharyngeal intubation (NPT). A trial of extubation is then undertaken on at least two separate occasions over a 2-4 week period. If the infant fails extubation with repeated obstruction and desaturation, then internal mandibular distraction is considered providing there is adequate bone to accommodate the appliances. The internal distraction devices are inserted via a submandibular approach and bilateral osteotomies are performed as posteriorly as possible from the retromolar region to the angle of the mandible to accommodate the device. The activation arms emerge below the auricles and distraction is performed at 1.5 mm per day for 10 days followed by a consolidation period of 6-8 weeks [Figure 4]. Most infants are predictably extubated at days 4-5 postoperatively with complete resolution of obstruction and are usually discharged approximately 2 weeks following the procedure.

Figure 4.

Nasopharyngeal-dependent infant with Pierre Robin sequence and micrognathia for mandibular distraction. (a) Preoperative lateral facial view, (b) Submandibular access for osteotomy, (c) Schematic diagram of distractor position, (d) Post-distraction lateral mandibular radiograph

Further supporting evidence for this technique in the management of upper airway obstruction continues to emerge. Miloro et al. reported on 35 syndromic patients who underwent DO for upper airway obstruction.[46] None of the patients required a tracheostomy post-distraction and those with a preexisting tracheostomy were successfully decannulated. Radiographic imaging revealed a mean increase in the posterior airway space of 12 mm. Tibesar et al. reported a long-term follow up of patients who underwent DO with a mean follow up of 7.6 years.[47] Of 32 patients, only 4 patients remained tracheotomy-dependent and improved feeding was noted, with no need of gastrostomy tube placement. Anatomical changes post-distraction using CT scans have also been shown to increase the distance between the base of tongue and posterior pharyngeal wall by a mean of 141%.[48]

CONCLUSIONS

In patients with craniofacial syndromes, the skeletal deficiencies may result in serious functional deficits and aesthetic compromise. Traditional orthognathic surgery is limited in being able to correct the anatomical anomalies at a young age and distraction of the craniofacial skeleton, as part of a staged approach, has been a most beneficial additional option for managing craniofacial deformities. To produce stable and aesthetic results, distraction in combination with traditional orthognathic surgery, remains the best approach in skeletal correction to achieve a functional occlusion and good facial balance.

The increasing recognition of upper airway obstruction in craniofacial syndromes has also focused attention on the potential for early correction using distraction techniques, particularly in the mid-face for the syndromic craniosynostoses and in patients with micrognathia, such as Pierre Robin sequence and related conditions.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: No.

REFERENCES

- 1.Swennen G, Schliephake H, Dempf R, Schierle H, Malevez C. Craniofacial distraction osteogenesis: A review of literature: Part 1: Clinical studies. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;30:89–103. doi: 10.1054/ijom.2000.0033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matsumoto K, Nakanishi H, Seike T, Shinno K, Hirabayashi S. Application of distraction technique to scaphocephaly. J Craniofac Surg. 2000;11:172–6. doi: 10.1097/00001665-200011020-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cho BC, Hwang SK, Uhm KL. Distraction osteogenesis of the cranial vault for the treatment of craniofacial synostosis. J Craniofac Surg. 2004;15:135–44. doi: 10.1097/00001665-200401000-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wiberg A, Magdum S, Richards PG, Jayamohan J, Wall SA, Johnson D. Posterior calvarial distraction in craniosynostosis- An evolving technique. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2012;40:799–806. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2012.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ko EW, Chen PK, Tai IC, Huang CS. Fronto-facial monobloc distraction in syndromic craniosynostosis.Three-dimensional evaluation of treatment outcome and facial growth. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;41:20–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2011.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Komuro Y, Yanai A, Hayashi A, Nakanishi H, Miyajima M, Arai H. Cranial reshaping employing distraction and contraction in the treatment of sagittal synostosis. Br J Plast Surg. 2005;58:196–201. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2004.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.White N, Evans M, Dover MS, Noons P, Solanki G, Nishikawa H. Posterior calvarial vault expansion using distraction osteogenesis. Childs Nerv Syst. 2009;25:231–6. doi: 10.1007/s00381-008-0758-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen SR, Rutrick RE, Burnstein FD. Distraction osteogenesis of the human craniofacial skeleton: Initial experience with new distraction system. J Craniofac Surg. 1995;6:368–74. doi: 10.1097/00001665-199509000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pijpers M, Poels PJ, Vaandrager JM, de Hoog M, van den Berg S, Hoeve HJ, et al. Undiagnosed obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in children with syndromal craniofacial synostosis. J Craniofac Surg. 2004;15:670–4. doi: 10.1097/00001665-200407000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barden RC, Ford ME, Jensen AG, Rogers-Salyer M, Salyer KE. Effects of craniofacial deformity in infancy on the quality of mother- infant interactions. Child Dev. 1989;60:819–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1989.tb03513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shand JM, Smith KS, Heggie AA. The role of distraction osteogenesis in the management of craniofacial syndromes. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2004;16:525–40. doi: 10.1016/j.coms.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nout E, Cesteleyn LL, van der Wal KG, van Adrichen LN, Mathijssen IM, Wolvius EB. Advancement of the midface, from conventional Le Fort III osteotomy to Le Fort III distraction: Review of the literature. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;37:781–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fearon JA. Halo distraction of the Le Fort III in syndromic craniosynostosis: A long-term assessment. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115:1524–36. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000160271.08827.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu JC, Fearon J, Havlik RJ, Buchman SR, Polley JW. Distraction osteogenesis of the craniofacial skeleton. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114:1E–20E. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000128965.52013.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fearon JA. The Le Fort III osteotomy: To distract or not to distract? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107:1091–103. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200104150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cedars MG, Linck DL, Chin M, Toth BA. Advancement of the midface using distraction techniques. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;103:429–41. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199902000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holmes AD, Wright GW, Meara JG, Heggie AA, Probert TC. Le Fort III internal distraction in syndromic craniosynostosis. J Craniofac Surg. 2002;13:262–72. doi: 10.1097/00001665-200203000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iannetti G, Fadda T, Agrillo A, Poladas G, Filiaci F. LeFort III advancement with and without osteogenesis distraction. J Craniofac Surg. 2006;17:536–43. doi: 10.1097/00001665-200605000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moore MH, Abbott AH. Extradural deadspace after infant fronto- orbital advancement in Apert syndrome. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 1996;33:202–5. doi: 10.1597/1545-1569_1996_033_0202_edaifo_2.3.co_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Polley JW, Figueroa AA. Management of severe maxillary deficiency in childhood and adolescence through distraction osteogenesis with an external, rigid distraction device. J Craniofac Surg. 1997;8:181–5. doi: 10.1097/00001665-199705000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohen SR, Holmes RE. Internal Le Fort III distraction with biodegradable devices. J Craniofac Surg. 2001;12:264–72. doi: 10.1097/00001665-200105000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burstein FD, Williams JK, Hudgins R, Graham L, Teague G, Paschal M, et al. Single- stage craniofacial distraction using resorbable devices. J Craniofac Surg. 2002;13:776–82. doi: 10.1097/00001665-200211000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meling TR, Hogevold HE, Due-Tonnessen BJ, Skjelbred P. Midface distraction osteogenesis: Internal vs. external devices. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;40:139–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2010.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nadjmi N, Schutyser F, Van Erum R. Trans-sinusal maxillary distraction for correction of midfacial hypoplasia: Long-term clinical results. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;35:885–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2006.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee DW, Ham KW, Kwon SM, Lew DH, Cho EJ. Dual midfacial distraction osteogenesis for Crouzon syndrome: Long-term follow-up study for relapse and growth. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;70:e242–51. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2011.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meazzini MC, Allevia F, Mazzoleni F, Ferrari L, Pagnoni M, Iannetti G, et al. Long-term follow-up of syndromic craniosynostosis after Le Fort III halo distraction: A cephalometric and CT evaluation. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2012;65:464–72. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2011.09.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mommaerts MY, Nagy K. Is early osteodistraction a solution for the ascending ramus compartment in hemifacial microsomia? A literature study. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2002;30:201–7. doi: 10.1054/jcms.2002.0314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Posnick JC. Surgical correction of mandibular hypoplasia in hemifacial microsomia: A personal perspective. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1998;56:639–50. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(98)90466-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaban LB, Padwa BL, Mulliken JB. Surgical correction of mandibular hypoplasia in hemifacial microsomia: The case for treatment in early childhood. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1998;56:628–38. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(98)90465-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaban LB, Mulliken JB, Murray JE. Three-dimensional approach to analysis and treatment of hemifacial microsomia. Cleft Palate J. 1981;18:90–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Polley JW, Figueroa AA, Liou EJ, Cohen M. Longitudinal analysis of mandibular asymmetry in hemifacial microsomia. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;99:328–39. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199702000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Padwa BL, Zaragoza SM, Sonis AL. Proximal segment displacement in mandibular distraction osteogenesis. J Craniofac Surg. 2002;13:293–6. doi: 10.1097/00001665-200203000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meazzini MC, Mazzoleni F, Bozzetti A, Brusati R. Comparison of mandibular vertical growth in hemifacial microsomia patients treated with early distraction or not treated: Follow up till the completion of growth. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2012;40:105–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vos MD, Baas EM, de Lange J, Bierenbroodspot F. Stability of mandibular advancement procedures: Bilateral sagittal split osteotomy versus distraction osteogenesis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;38:7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2008.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baas EM, Pijpe J, de Lange J. Long term stability of mandibular advancement procedures: Bilateral sagittal split osteotomy versus distraction osteogenesis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;41:137–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2011.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ow A, Cheung LK. Bilateral sagittal split osteotomies and mandibular distraction osteogenesis: A randomized controlled trial comparing skeletal stability. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2010;109:17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Molina F, Monasterio FO. Mandibular elongation and remodeling by distraction: A farewell to major osteotomies. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;96:825–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abel F, Bajaj Y, Wyatt M, Wallis C. The successful use of the nasopharyngeal airway in Pierre Robin sequence: An 11-year experience. Arch Dis Child. 2012;97:331–4. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2011-301134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Allen GC. Mandibular distraction osteogenesis for neonatal airway obstruction. Operative Techniques in Otolaryngology. 2005;16:187–93. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Steinberg B, Fattahi T. Distraction osteogenesis in management of pediatric airway: Evidence to support its use. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;63:1206–8. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2005.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wetmore RF, Marsh RR, Thompson ME, Tom LW. Pediatric tracheostomy: A changing procedure? Ann Otol Rhniol Laryngol. 1999;108:695–9. doi: 10.1177/000348949910800714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jiang D, Morrison GA. The influence of long-term tracheostomy on speech and language development in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2003;67:S217–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2003.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Denny AD, Talisman R, Hanson PR, Recinos RF. Mandibular distraction osteogenesis in very young patients to correct airway obstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108:302–11. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200108000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Denny A, Kalantarian B. Mandibular distraction in neonates: A strategy to avoid tracheostomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109:896–904. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200203000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Perlyn CA, Schmelzer RE, Sutera SP, Kane AA, Govier D, Marsh JL. Effect of distraction osteogenesis of the mandible on the upper airway volume and resistance in children with micrognathia. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109:1809–18. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200205000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miloro M. Mandibular distraction osteogenesis for pediatric airway management. J Oral Maxillfac Surg. 2010;68:1512–23. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.09.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tibesar RJ, Scott AR, McNamara C, Sampson D, Lander TA, Sidman JD. Distraction osteogenesis of the mandible for airway obstruction in children: Long-term results. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;143:90–6. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2010.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mohamed AM, Bishri AA, Mohamed AH. Distraction osteogenesis as followed by CT scan in Pierre Robin sequence. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2011;39:412–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2010.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]