Background

Brugada syndrome is a rare condition associated with increased risk of ventricular tachyarrhythmias and sudden cardiac death.1 Given its potential consequences, emergency physicians, internists and cardiologists must be familiar with the electrocardiographic features of Brugada syndrome. The typical ECG features are recognised to fluctuate,2 and are known to be revealed by several precipitants including febrile illness.3 4 The appearance of a Brugada-type ECG with fever may indicate an elevated risk of arrhythmia or sudden cardiac death. The following case describes the incidental ECG finding of the Brugada pattern in a patient who presented with fever and cellulitis. These findings resolved with treatment of the precipitating medical illness.

Case presentation

We report a 74-year-old, white man who presented to the emergency department with a 4-day history of fever associated with lower left leg pain, swelling and erythema. Further review of systems was unremarkable. Specifically, the patient denied any history of chest pain, dyspnoea, palpitations, syncope or presyncope.

The patient's history included hypertension, dyslipidaemia and benign prostatic hyperplasia. The patient also endorsed an episode of cellulitis 7 years prior to the current presentation that was treated with oral antibiotics without complications. His medications were rosuvastatin, alfuzosin, a combination of diclofenac and misoprostol, and vitamin D supplements. He did not report any medication allergies. He denied any significant exposure to cigarettes, alcohol or illicit substances.

His family history was unremarkable. He did not report any prior history of sudden death in relatives.

On examination, the patient did not appear to be in distress. He was febrile (39.6°C) and tachycardic (heart rate 121 bpm). Remaining vital signs were within normal limits. On the lateral aspect of the lower left leg proximal to the ankle, there was a large, non-raised, tender area of erythema with poorly defined borders, consistent with cellulitis. Cardiovascular examination revealed normal heart sounds without any audible murmurs. Jugular venous pressure was within normal limits. The remainder of the physical examination was unremarkable.

Investigations

Laboratory investigations revealed a white cell count of 17.1 × 10−9/l (neutrophils 14.9 × 10−9/l). Electrolytes, creatine, and troponin values were within normal limits. Chest x-ray was unremarkable. Cultures of blood and urine did not reveal additional infectious sources of fever. A Doppler ultrasound of the left leg was negative for a proximal deep venous thrombosis (DVT).

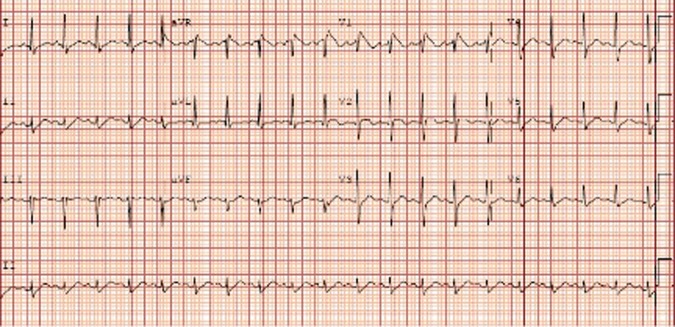

ECG revealed sinus tachycardia at 121 bpm. There was ST segment elevation with downsloping descent and T wave inversion in leads V1 and V2. Incomplete right bundle branch block QRS morphology (QRS duration 102 ms) was present (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Electrocardiogram obtained in the emergency department while the patient was febrile demonstrating downsloping ST segment elevation with T wave inversions in leads V1–V2.

Differential diagnosis

The finding of ST segment elevation raised the possibility of acutely life-threatening diagnoses, including an ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome. However, this patient did not have symptoms of myocardial ischaemia, and serial troponin values were not consistent with a myocardial infarction. The lack of suggestive symptoms and the localised nature of the ST elevation argued against acute pericarditis. As mentioned, the patient had a Doppler ultrasound that was negative for DVT and he did not have any specific risk factors for a pulmonary embolus. There was no history of blunt trauma.

No previous ECGs were available. It is unknown if the patient had a pre-existing right bundle branch block or early repolarisation.

Transthoracic echocardiography revealed only mild left ventricular hypertrophy. There was no abnormality of the right ventricle to suggest arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy.

Given the above findings, the patient's ECGs were believed to be most consistent with the Brugada pattern.

Treatment

The patient was admitted to hospital with a primary diagnosis of cellulitis. It was felt that that fever had unmasked the Brugada pattern seen on his ECGs.

He was treated with intravenous cefazolin. Acetaminophen 1000 mg was given every 6 h to reduce his temperature. The patient was placed on a continuous cardiac monitor. Consultation from the cardiac electrophysiology service was obtained.

Outcome and follow-up

Our patient's cellulitis initially progressed despite intravenous antibiotics. He was seen in consultation by the infectious diseases and plastic surgery services. Both suggested continuing intravenous cefazolin and supportive care. The area of erythema began to regress on day 6 of hospitalisation and the patient did not experience any fevers after the second day in hospital.

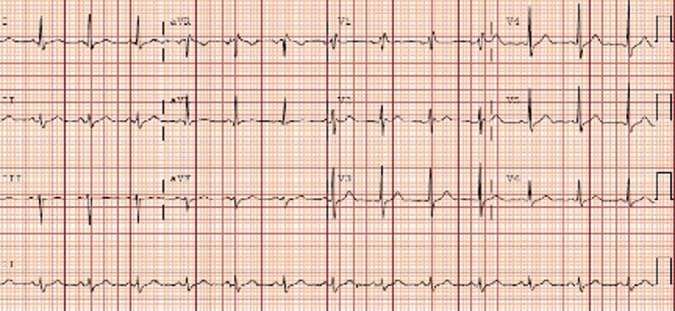

The patient was observed on remote continuous cardiac monitoring for 5 days, with no significant arrhythmias identified. ECGs were obtained and the Brugada pattern persisted for the first 2 days in hospital. On the third day in hospital once the patient was afebrile, the ST segment elevation had diminished, leaving an incomplete right bundle branch block (figure 2). His ECGs were unchanged for the remainder of his hospital stay.

Figure 2.

Electrocardiogram obtained on day X of hospital admission after resolution of fever. Previously seen ST segment elevation has resolved, with residual incomplete right bundle branch block.

Repeat questioning confirmed no prior episodes of syncope, presyncope or a family history of sudden cardiac death. He did not develop any cardiac symptoms during his admission and given the absence of clinical manifestations of Brugada syndrome, it was the opinion of the cardiac electrophysiology consultants that the patient had a low-risk phenotype and did not require prophylactic implantable cardiac defibrillator (ICD) during admission.

The patient was discharged home on day 11. Outpatient follow-up was arranged with the cardiac electrophysiology service for further assessment. He was given a prescription for oral cephalexin to complete 2 weeks of antibiotic therapy. When seen in follow-up by the electrophysiology service, the patient chose not to pursue further investigations including genetic testing, pharmacological provocation testing or cardiac MRI. Family screening of first-degree relatives for ECG findings of Brugada syndrome was unremarkable.

Discussion

Brugada syndrome is an arrhythmogenic disease responsible for sudden cardiac death in individuals with structurally normal hearts.1 Three ECG patterns of Brugada syndrome have been described. Type 1 features ≥2 mm of downsloping or coved shaped ST segment elevation followed by a negative T wave. Type 2 has ≥2 mm of ST elevation at the terminal portion of the ST segment, with a positive T wave that creates a saddleback appearance. Type 3 may have either coved shaped or saddleback ST-segment elevation with <1 mm magnitude of elevation at the terminal portion.

Definitive diagnosis of the Brugada syndrome requires the presence of a Type 1 ECG pattern, or conversion of a Type 2 or Type 3 pattern to Type 1 following provocation testing with a sodium channel blocker, plus one the following: documented ventricular fibrillation, self-terminating polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, family history of sudden cardiac death at age <45, rype 1 ECG pattern in a family member, electrophysiological induction of ventricular tachycardia, unexplained syncope felt consistent with a tachyarrhythmia or nocturnal agonal respirations.1

In total, 18–30% of cases of Brugada syndrome result from loss of function mutations in the SCN5A gene, which encodes a subunit of a cardiac sodium channel. Temperature-dependent gating changes in these sodium channels have been identified, suggesting a possible molecular mechanism for the appearance of the Brugada ECG patterns in febrile patients.5 Previous reports have documented Brugada ECG pattern arising in the context of a febrile illness such as pneumonia,6 bacteraemia,7 8 viral infections,8 9 gastrointestinal infections10 and mastitis.11

The approach to the management of Brugada syndrome has been outlined previously.1 However, there is a lack of guidance for physicians taking care of patients who develop the ECG findings of Brugada syndrome in the context of an acute febrile illness. It has been suggested that patients who present with a Brugada pattern ECG in the setting of an acute illness may be at very high risk for malignant arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death. In a retrospective study, 10 of 16 patients with Brugada pattern induced by fever developed ventricular tachyarrhythmia or syncope, including 4 patients who suffered sudden cardiac death.4 A retrospective case series of patients with known Brugada syndrome identified fever as a risk factor for cardiac arrest, and early use of acetaminophen was associated with a lower incidence of cardiac arrest.12

Non-pharmacological management of acute malignant arrhythmias or electrical storm in Brugada syndrome includes defibrillation/resuscitation if necessary, targeted treatment of fever, and cessation of arrhythmogenic drugs and substances (table 1). Pharmacological treatment includes intravenous isoproterenol/isoprenaline and/or quinidine.13 Enhancement of the ICa channels by isoproterenol/isoprenaline, and decreased outward potassium channel current by quinidine, stabilises cardiac sodium channels, which results in resolution of the ST-segment elevation in Brugada syndrome which has thought to be the precipitant of arrhythmias in Brugada syndrome.14

Table 1.

Drugs to be avoided in Brugada syndrome

| Cardiovascular | Antiarrhythmic agents/Sodium channel blocker |

| Class IA: ajmaline, cibenzoline, disopyramide, procainamide | |

| Class IC: flecainide, pilscainide, propafenone | |

| Beta-blocker: propranolol | |

| Calcium channel blocker: diltiazem, nifedipine | |

| Potassium channel blocker: nicorandil | |

| Nitrate: isosorbide dinitrate, nitroglycerine | |

| Psychiatric | Phenothiazine: cyamemazine, perphenazine |

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor: fluoxetine | |

| Tricyclic antidepressant: amitryptaline, nortryptaline, desipiramine, clomipramine | |

| Tetracyclic antidepressant: maprotiline | |

| Other | Dimenhydrinate, alcohol intoxication, cocaine intoxication |

Recommendations for ICD implantation in Brugada syndrome includes patients displaying the type 1 ECG pattern (either spontaneously or after sodium channel blockade) who present with aborted sudden death, and patients presenting with related symptoms such as syncope, seizure or nocturnal agonal respiration after non-cardiac causes of these symptoms have been ruled out.1 15 Asymptomatic patients displaying a type 1 ECG pattern (either spontaneously or after sodium channel blockade) should undergo electrophysiology studies. If inducible for ventricular arrhythmia, the patient should receive an ICD. If such electrophysiology studies are negative, the patient should be closely followed-up without prophylactic ICD implantation. Our patient was classified as low-risk phenotype as he was asymptomatic with spontaneous presentation of ECG findings of Brugada syndrome. Unfortunately, his decision not to pursue additional investigations prevented a definitive diagnosis of Brugada syndrome.

Learning points.

The Brugada syndrome can be revealed on ECG during a febrile illness.

Patients with an induced Brugada pattern on ECG may be at particularly high risk of malignant arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death. These patients should receive antipyretic medications and have their acute illness managed aggressively.

Follow-up with a specialist in cardiac electrophysiology and additional diagnostic testing after the acute illness has resolved is desired for any patient with an electrocardiographic Brugada pattern.

Footnotes

Correction notice: This article has been corrected since it was published online on 4 April 2013. The first author's name has been corrected.

Contributors: All authors were involved in the conception and design, acquisition of data and analysis, interpretation of data, drafting the article and final approval of the version published.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Antzelevitch C, Brugada P, Borggrefe M, et al. Brugada syndrome: report of the second consensus conference: endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society and the European Heart Rhythm Association. Circulation 2005;111:659–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Veltmann C, Schimpf R, Echternach C, et al. A prospective study on spontaneous fluctuations between diagnostic and non-diagnostic ECGs in Brugada syndrome: implications for correct phenotyping and risk stratification. Eur Heart J 2006;272544–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lamelas P, Labadet C, Spernanzoni F, et al. Brugada electrocardiographic pattern induced by fever. World J Cardiol 2012;4:84–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Junttila MJ, Gonzalez M, Lizotte E, et al. Induced Brugada-type electrocardiogram, a sign for imminent malignant arrhythmias. Circulation 2008;117:1890–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dumaine R, Towbin JA, Brugada P, et al. Ionic mechanisms responsible for the electrocardiographic phenotype of the Brugada syndrome are temperature dependent. Circ Res 1999;85:803–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sovari AA, Prasun MA, Kocheril AG, et al. Brugada syndrome unmasked by pneumonia. Tex Heart Inst J 2006;33:501–4 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singla A, Coats W, Flaker GC. A 46-year-old man with fever, ST-segment elevation. Cleve Clin J Med 2011;78:286–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baranchuk A, Simpson CS. Brugada syndrome coinciding with fever and pandemic (H1N1) influenza. CMAJ 2011;183:582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Serletis-Bizios A, Azevedo ER, Singh SM. Unmasking of Brugada syndrome during a febrile episode. Can J Cardiol 2009;25:239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Makaryus JN, Verbsky J, Schwartz S, et al. Fever associated with gastrointestinal shigellosis unmasks probable Brugada syndrome. Case Report Med 2009;2009:492031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ambardekar AV, Lewkowiez L, Krantz MJ. Mastitis unmasks Brugada syndrome. Int J Cardiol 2009;132:e94–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amin AS, Meregalli PG, Bardai A, et al. Fever increases the risk for cardiac arrest in the Brugada syndrome. Ann Intern Med 2008;149:216–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Postema PG, Wolpert C, Amin AS, et al. Drugs and Brugada syndrome patients: review of the literature, recommendations, and an up-to-date website (http://www.brugadadrugs.org). Heart Rhythm 2009;6:1335–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jongman JK, Jepkes-Bruin N, Ramdat Misier AR, et al. Electrical storms in Brugada syndrome successfully treated with isoproterenol infusion and quinidine orally. Neth Heart J 2007;15:151–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olde Nordkamp LR, Wilde AA, Tijssen JG, et al. The ICD for primary prevention in patients with inherited cardiac diseases: indications, use, and outcome: a comparison with secondary prevention. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2013;6:91–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]