Abstract

Giant basal cell carcinomas (GBCC) are rare, accounting for <1% of BCCs. Those occurring on the anterior chest wall are a very rare subset that brings particular reconstructive challenges. We describe a 75-year-old man whose 13.5 cm diameter ulcerating GBCC on his left anterior chest came to medical attention following a fall. The lesion was resected en-bloc with adjacent ribs, and reconstructed with an omental flap, superiorly pedicled vertical rectus abdominus myocutaneous (VRAM) flap and split skin grafting. While the myriad reasons for delayed presentation of giant cutaneous malignancies are well documented, the complex nature of reconstruction and requirement for an integrated multidisciplinary approach are less so. It is of importance to note that the cicatricial nature of these lesions may result in a much larger defect requiring reconstruction than appreciated prior to resection. Documented cases of anterior chest wall GBCC and the treatment strategies employed are reviewed.

Background

Basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) >5 cm diameter (T3 BCCs) have been described as ‘giant’ BCCs (GBCCs) and account for <1% of all BCCs.1 These lesions often demonstrate locally aggressive behaviour, with infiltration of adjacent structures, appreciable rates of metastasis, high rates of local recurrence and poor prognosis.2 Indeed, some have suggested that such tumours, when observed with locally destructive behaviour, metastasis or recurrence despite multiple excision attempts, may be referred to as ‘horrifying’ BCCs.3

Risk factors for the development of GBCC include delayed presentation, patient neglect, recurrence after previous treatment, aggressive histological subtypes (morpheaform, micronodular and metatypical) or a history of radiation exposure.1 The most comprehensive systemic review of GBCC reveals that this is principally a disease of men in their seventh decade, and that lesions have typically been present for 14.5 years and sited on the back, face or upper extremity. Anterior thoracic lesions are very rare. Significantly, in their review of 51 cases, metastasis was seen in 17.6% at presentation (in contrast to 0.1% incidence for all BCCs) and 12% of patients developed recurrence despite wide local excision±adjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy.2 Their overall reported ‘cure’ rate was 61.7% at 2 years.2 Others report that the incidence of metastasis or fatal outcome is 45% for GBCC >10 cm diameter.4

GBCCs are often regarded as pathognomonic of neglect, with causes for delay to presentation including fear, old age, psychiatric comorbidity, low social class and inadequate hygiene.5 The fact that patients have not sought medical attention earlier often heralds untreated comorbidities that conspire to make treatment of the skin malignancy a multidisciplinary affair. On account of their rarity there are no established guidelines for GBCC treatment. Recommendations are derived from at best level 4 evidence. Single modality treatment by radiotherapy or chemotherapy appears to offer only palliative benefit and the mainstay of treatment is by resection. What constitutes an ‘adequate’ margin is unknown, although one paper suggests that up to 3 cm may be necessary.2 The resultant defect may necessitate reconstruction on a scale infrequently encountered by skin cancer teams. Multimodal treatment with photodynamic therapy followed by imiquimod may reduce tumour size by up to 40% prior to resection6 and ameliorate the reconstructive challenge by enabling the use of local flaps or smaller areas of split skin grafting.

Case presentation

We present the case of a 75-year-old man who presented to the emergency department following a mechanical fall at home. Examination revealed a 13.5 cm diameter ulcerating tumour on the left lower anterior thoracic wall (figure 1), a 6.5 cm diameter fungating tumour on the dorsum of the left foot, and a 3 cm diameter fungating tumour overlying the right scapula. There was no palpable lymphadenopathy. Initial investigations revealed an haemoglobin (Hb) of 4.5 g/dl with profoundly microcytic hypochromic cells. The chest wall lesion was actively bleeding, albeit at a slow rate and the patient revealed that it had done so for several months. The chest wall and pedal lesion had been present for at least 10 years, and the scapula lesion for perhaps 5 years. The patient led a reclusive lifestyle, acting as the main carer for his wife with dementia and had not sought any medical attention for approximately 30 years.

Figure 1.

Giant chest wall basal cell carcinoma at initial presentation.

Investigations

Staging CT chest/abdomen/pelvis revealed no lymphadenopathy or metastatic disease. MRI with gadolinium contrast demonstrated erosion to costal cartilage and periosteum with extension into the left external oblique and superior left rectus abdominus but no penetration through the abdominal wall or mediastinal extension.

Incisional biopsies were taken of all lesions. Histology demonstrated a nodular/infiltrative BCC of the left anterior chest, moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (at least Clark level IV) on the left foot, and nodular BCC overlying the right scapula.

Treatment

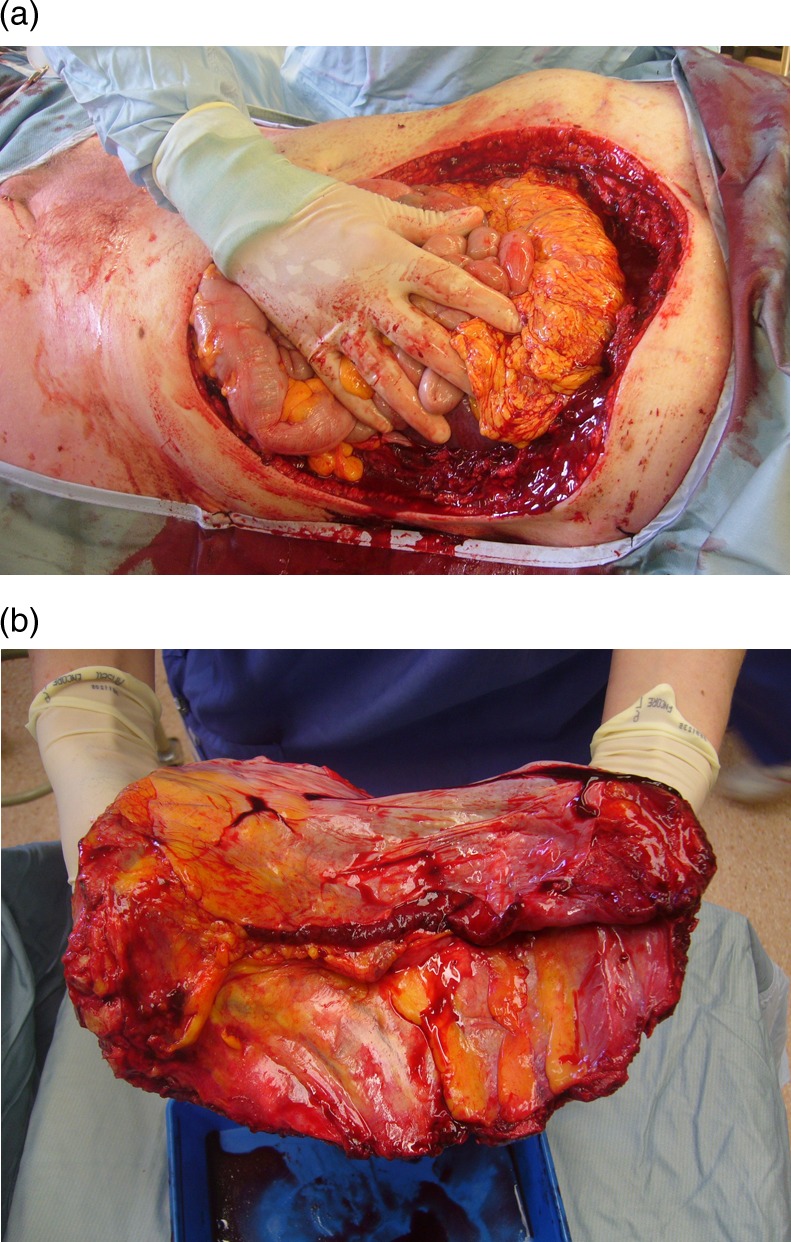

The chest wall BCC was excised with a 3 cm margin in conjunction with a cardiothoracic consultant, including several ribs, partial diaphragm and involved abdominal musculature in the resection specimen (figure 2). Intraoperative frozen section was used to guide resection margins. Prolene mesh was laid over the pericardium to prevent cardiac compression. Porcine acellular dermis (Collamed) overlaid both the chest and peritoneal defects. The diaphragm was reattached to the newly created costal margin. Over this an omental flap was placed to cover the superior 2/3 of the defect, and a superiorly pedicled vertical rectus abdominus myocutaneous (VRAM) flap was used to cover the inferior 1/3 of the defect. Split skin graft was placed over the omental flap (figure 3).

Figure 2.

(A) Extent of the defect requiring reconstruction following excision; (B) excision specimen (posterior view).

Figure 3.

Immediate postoperative appearance of pedicled vertical rectus abdominus myocutaneous and split skin grafting to omental flap.

The pedal SCC was excised and split skin grafted during the same procedure. The back BCC was excised and the defect closed primarily under local anaesthetic at a second operation.

All lesions were completely excised, with peripheral and deep margins of 15 and 10 mm, respectively, for the chest wall BCC.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit for routine monitoring in the perioperative period. On returning to the ward he underwent a month of intensive physiotherapy, occupational therapy and nutritional supplementation prior to discharge home. There were no significant postoperative medical or wound healing complications.

Discussion

Our patient's presentation is not atypical of other GBCC. He was clearly aware of the sinister nature of the chest wall lesion and of the pain and maladour that it caused, but chose not to seek medical attention due to a combination of fear and prioritisation of his wife's care. Others have noted that external events, such as our patient's fall, are often the catalyst that finally impels them to seek medical advice.5 Synchronous lesions are not uncommon.7

GBCCs of the anterior thorax are a very rare subset (see table 1). Of the six described cases that we are aware of, only one was judged unsuitable for either surgery or radiotherapy on account of mediastinal infiltration and occlusion of the left brachiocephalic vein.8 All other cases were treated by surgical excision with or without neoadjuvant or adjuvant therapy. A chest wall reconstruction is only reported in one case of primary chest wall GBCC9 and one case of recurrent disease.10 We wish to highlight how the cicatricial nature of these GBCCs distorts local anatomy and can result in much larger postexcisional defects than may have been appreciated preoperatively (figure 2). This is apparent from the images in Vallely and Stern's paper9 but not explicitly stated in any of the cases.

Table 1.

Published cases of anterior thoracic giant basal cell carcinoma

| Authors | Patient age | Gender | Histology | Size (cm) | Duration (years) | Mets? | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lorenzini et al8 | 81 | M | Infiltrative | 6×2 | 4 months | No | None |

| Lackey et al7 | 43 | M | ? | 16 | ? | ? | Excise+TRAM |

| Madan et al6 | 62 | F | Nodular/superficial | 8×5 | 30 years | No | PDT+imiquimod+local flap |

| Archontaki et al2 | 63 | M | Nodular | 20×15 | ? | No | Excise+flap+radiotherapy |

| Varga et al5 | 84 | M | ? | ? | 1 year | No | Excise+SSG |

| Vallely and Stern9 | 58 | M | ? | ? | ? | ? | Excise+Gore-Tex patch+LD flap+SSG |

? indicates where data was unavailable in the cited paper.

Furthermore, our case demonstrates the multidisciplinary approach that must be adopted when planning treatment for GBCC. Our patient did not undergo resection until 5 weeks after admission, by which time he had been medically and nutritionally optimised and also been reviewed by physiotherapy. Surgery was undertaken by both an experienced sarcoma plastic surgeon and cardiothoracic surgeon familiar with chest wall reconstruction. Single stage excision and reconstruction of these large tumours is challenging,7 but results in considerable increase in quality of life. At 2 months postsurgery our patient's wounds have healed well (figure 4). Given the high documented rates of recurrence2 he will be kept under close secondary care follow-up.

Figure 4.

Appearances 8 weeks postreconstruction.

Learning points.

Rates of metastasis and recurrence postresection are appreciably higher for ‘giant’ (>5 cm diameter) basal cell carcinomas than for non-giant tumours.

The cicatricial nature of these lesions can result in much larger postexcisional defects requiring reconstruction than appreciated preoperatively.

The milieu of factors contributing to delayed presentation of these tumours necessitates a multidisciplinary approach to treatment, and surgery may have to be delayed until patients are appropriately investigated and medically optimised.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors have made substantial contributions conception, drafting, review and approval of the final draft of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Randle HW, Roenigk RK, Brodland DG. Giant basal cell carcinoma (T3): who is at risk? Cancer 1993;2013:1624–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Archontaki M, Stavrianos SP, Korkolis DP, et al. Giant basal cell carcinoma: clinicopathological analysis of 51 cases and review of the literature. Anticancer Res 2009;2013:2655–64 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horlock N, Wilson GD, Daley FM, et al. Cellular proliferation characteristics do not account for the behaviour of horrifying basal cell carcinoma. A comparison of the growth fraction of horrifying and non-horrifying tumours. Br J Plast Surg 1998;2013:59–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Snow SN, Sahl W, Lo JS, et al. Metastatic basal cell carcinoma. Cancer 1994;2013:328–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Varga E, Korom I, Raskó Z, et al. Neglected basal cell carcinomas in the 21st Century. J Skin Cancer 2011;2011:10.1155/2011/392151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Madan V, West CA, Murphy JV, et al. Sequential treatment of giant basal cell carcinomas. J Plast Reconstruct Aesthet Surg 2009;2013:e368–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lackey PL, Sargent LA, Wong L, et al. Giant basal cell carcinoma surgical management and reconstructive challenges. Ann Plast Surg 2007;2013:250–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lorenzini M, Gatti S, Giannitrapani A. Giant basal cell carcinoma of the thoracic wall: a case report and review of the literature. Br J Plast Surg 2005;2013:1007–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vallely MP, Stern HS. Giant anterior chest wall basal cell carcinoma. Eur J Cardiothoracic Surg 2011;2013:793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cunnick GH, Sayer RE. Chest wall resection and reconstruction for metastatic basal cell carcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol 1997;2013:189–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]