Abstract

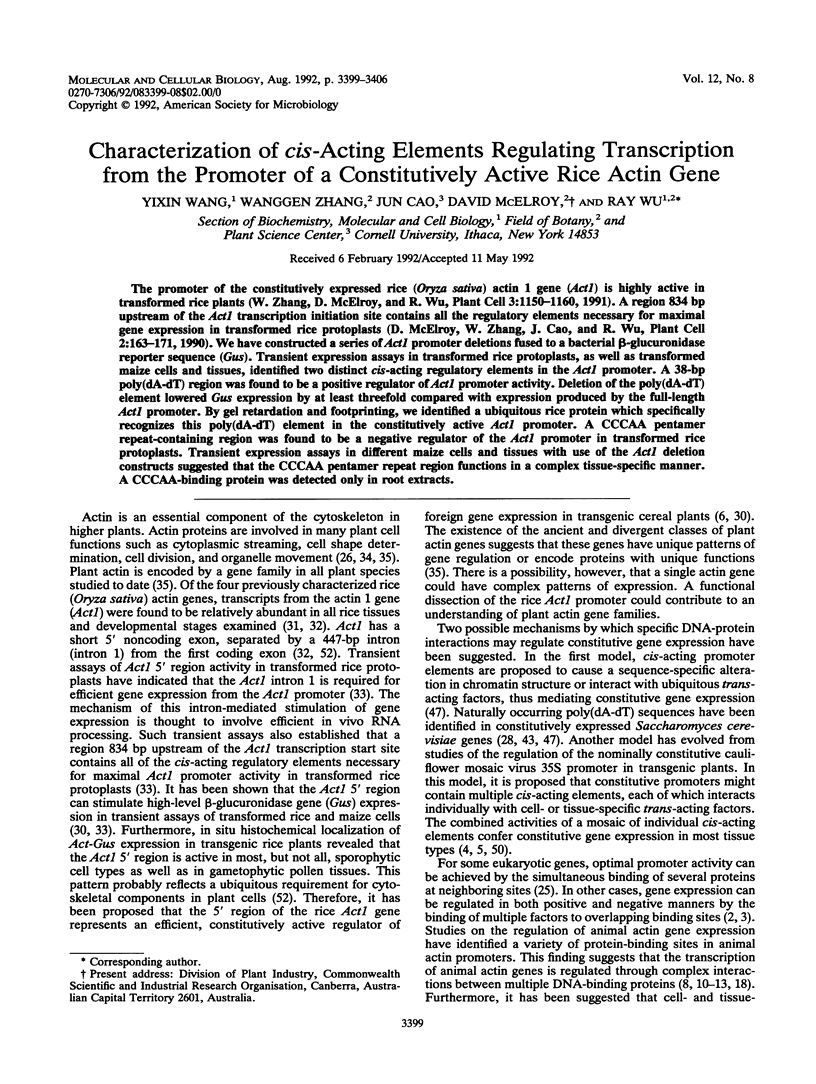

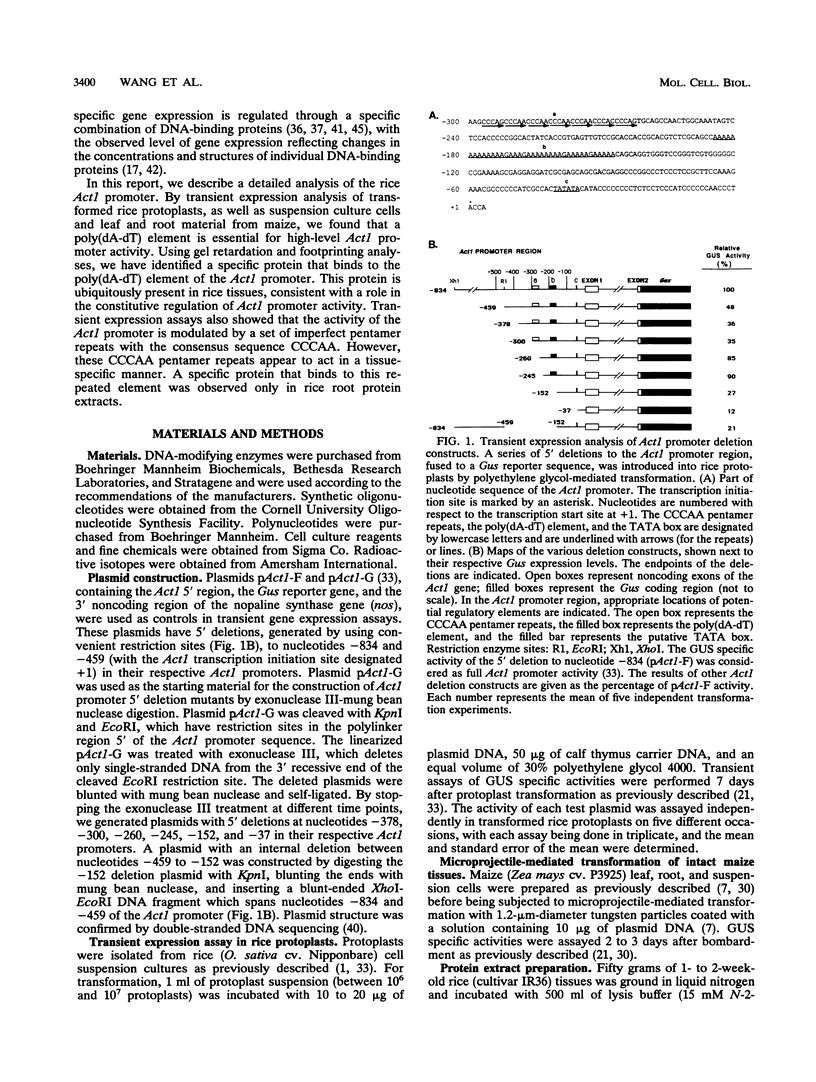

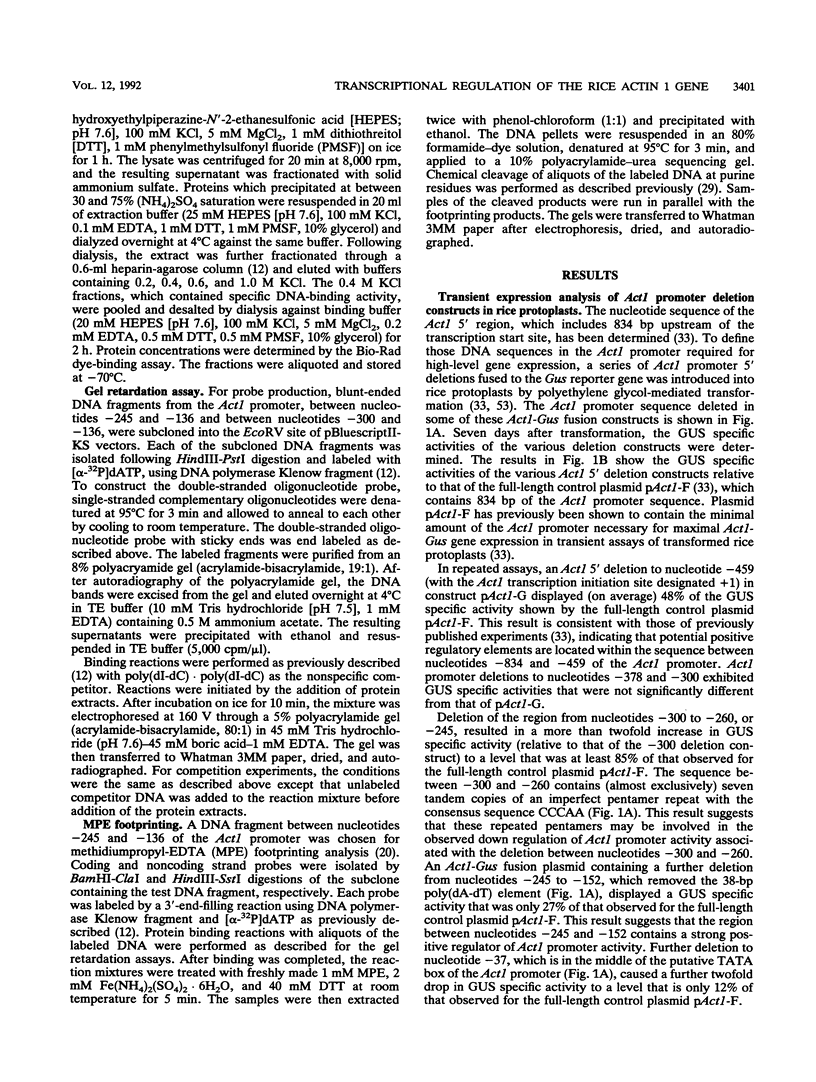

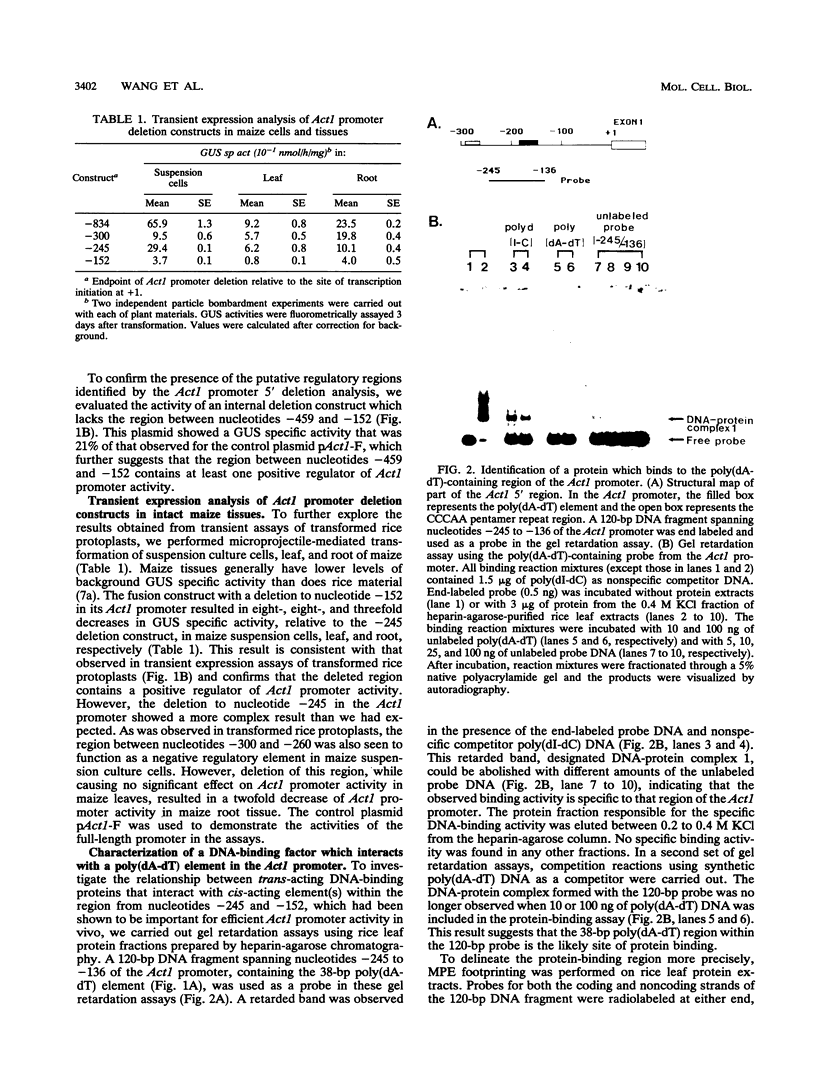

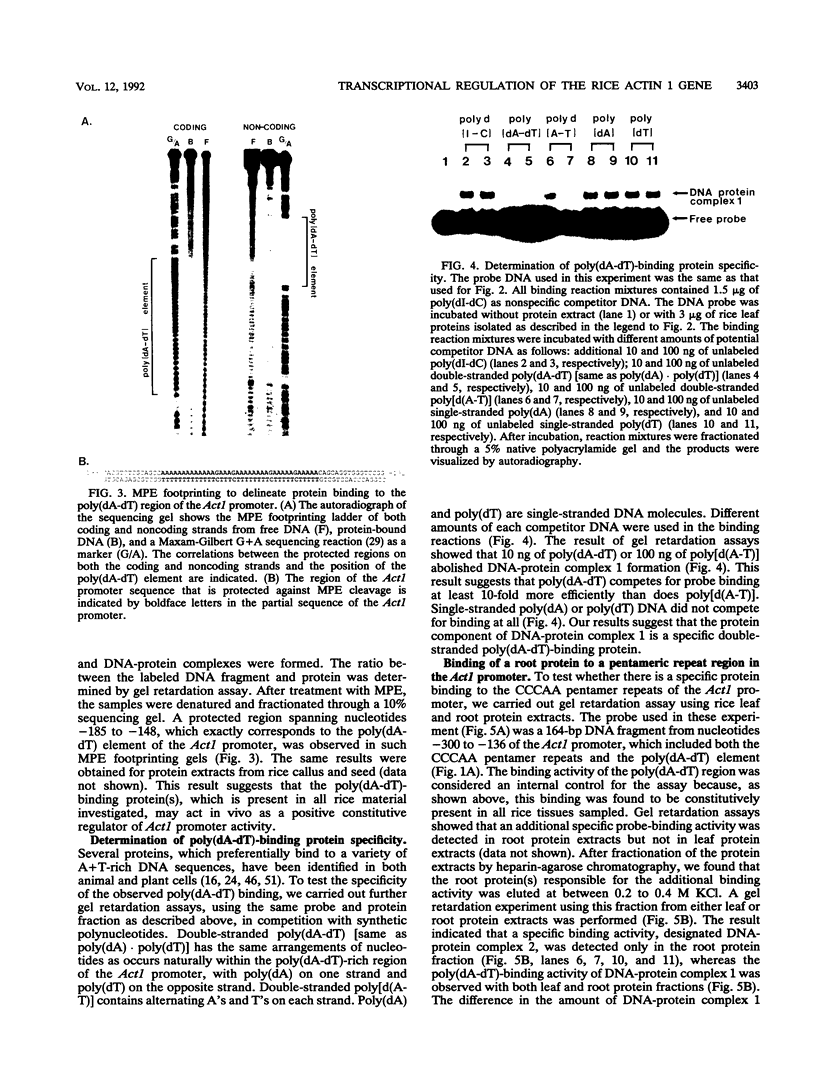

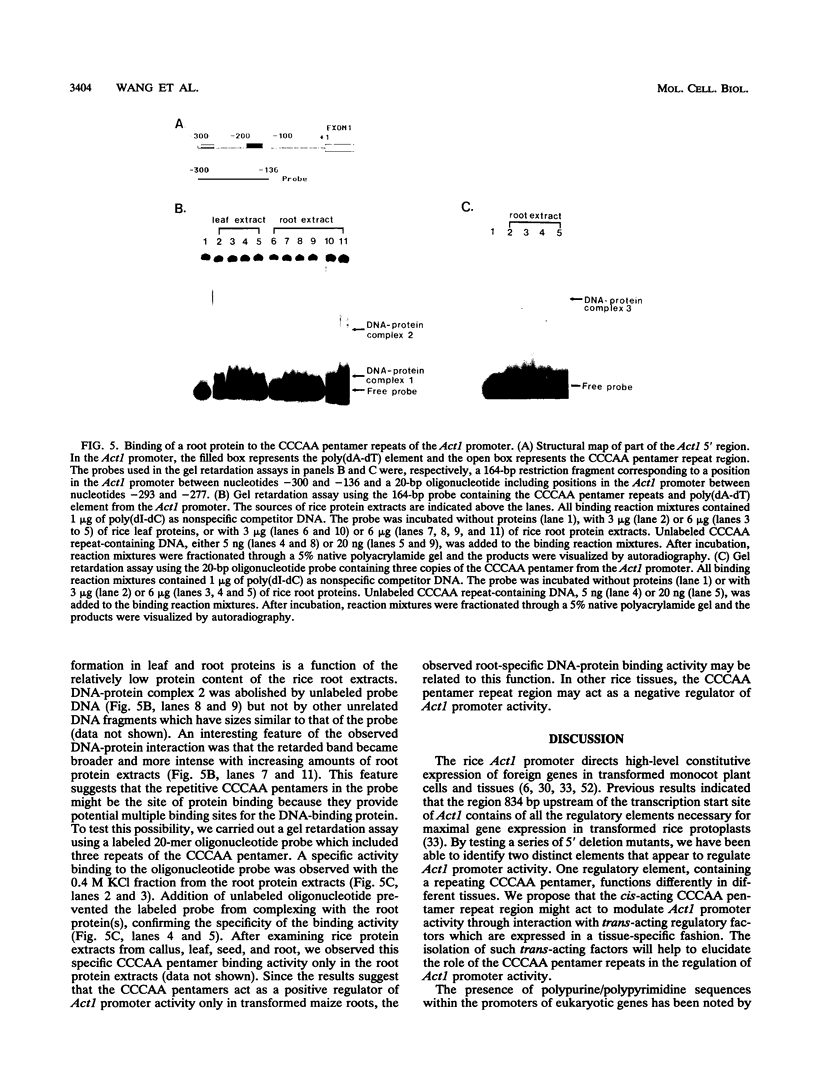

The promoter of the constitutively expressed rice (Oryza sativa) actin 1 gene (Act1) is highly active in transformed rice plants (W. Zhang, D. McElroy, and R. Wu, Plant Cell 3:1150-1160, 1991). A region 834 bp upstream of the Act1 transcription initiation site contains all the regulatory elements necessary for maximal gene expression in transformed rice protoplasts (D. McElroy, W. Zhang, J. Cao, and R. Wu, Plant Cell 2:163-171, 1990). We have constructed a series of Act1 promoter deletions fused to a bacterial beta-glucuronidase reporter sequence (Gus). Transient expression assays in transformed rice protoplasts, as well as transformed maize cells and tissues, identified two distinct cis-acting regulatory elements in the Act1 promoter. A 38-bp poly(dA-dT) region was found to be a positive regulator of Act1 promoter activity. Deletion of the poly(dA-dT) element lowered Gus expression by at least threefold compared with expression produced by the full-length Act1 promoter. By gel retardation and footprinting, we identified a ubiquitous rice protein which specifically recognizes this poly(dA-dT) element in the constitutively active Act1 promoter. A CCCAA pentamer repeat-containing region was found to be a negative regulator of the Act1 promoter in transformed rice protoplasts. Transient expression assays in different maize cells and tissues with use of the Act1 deletion constructs suggested that the CCCAA pentamer repeat region functions in a complex tissue-specific manner. A CCCAA-binding protein was detected only in root extracts.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Baldwin A. S., Jr, Sharp P. A. Two transcription factors, NF-kappa B and H2TF1, interact with a single regulatory sequence in the class I major histocompatibility complex promoter. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988 Feb;85(3):723–727. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.3.723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barberis A., Superti-Furga G., Busslinger M. Mutually exclusive interaction of the CCAAT-binding factor and of a displacement protein with overlapping sequences of a histone gene promoter. Cell. 1987 Jul 31;50(3):347–359. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90489-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benfey P. N., Chua N. H. The Cauliflower Mosaic Virus 35S Promoter: Combinatorial Regulation of Transcription in Plants. Science. 1990 Nov 16;250(4983):959–966. doi: 10.1126/science.250.4983.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benfey P. N., Ren L., Chua N. H. The CaMV 35S enhancer contains at least two domains which can confer different developmental and tissue-specific expression patterns. EMBO J. 1989 Aug;8(8):2195–2202. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08342.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll S. L., Bergsma D. J., Schwartz R. J. A 29-nucleotide DNA segment containing an evolutionarily conserved motif is required in cis for cell-type-restricted repression of the chicken alpha-smooth muscle actin gene core promoter. Mol Cell Biol. 1988 Jan;8(1):241–250. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.1.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W., Tabor S., Struhl K. Distinguishing between mechanisms of eukaryotic transcriptional activation with bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase. Cell. 1987 Sep 25;50(7):1047–1055. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90171-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow K. L., Hogan M. E., Schwartz R. J. Phased cis-acting promoter elements interact at short distances to direct avian skeletal alpha-actin gene transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991 Feb 15;88(4):1301–1305. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.4.1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow K. L., Schwartz R. J. A combination of closely associated positive and negative cis-acting promoter elements regulates transcription of the skeletal alpha-actin gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1990 Feb;10(2):528–538. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.2.528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung Y. T., Keller E. B. Regulatory elements mediating transcription from the Drosophila melanogaster actin 5C proximal promoter. Mol Cell Biol. 1990 Jan;10(1):206–216. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.1.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fascher K. D., Schmitz J., Hörz W. Role of trans-activating proteins in the generation of active chromatin at the PHO5 promoter in S. cerevisiae. EMBO J. 1990 Aug;9(8):2523–2528. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07432.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forde B. G., Freeman J., Oliver J. E., Pineda M. Nuclear factors interact with conserved A/T-rich elements upstream of a nodule-enhanced glutamine synthetase gene from French bean. Plant Cell. 1990 Sep;2(9):925–939. doi: 10.1105/tpc.2.9.925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankel A. D., Kim P. S. Modular structure of transcription factors: implications for gene regulation. Cell. 1991 May 31;65(5):717–719. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90378-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson T. A., Kedes L. Identification of multiple proteins that interact with functional regions of the human cardiac alpha-actin promoter. Mol Cell Biol. 1989 Aug;9(8):3269–3283. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.8.3269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagerman P. J. Sequence-directed curvature of DNA. Annu Rev Biochem. 1990;59:755–781. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.59.070190.003543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertzberg R. P., Dervan P. B. Cleavage of DNA with methidiumpropyl-EDTA-iron(II): reaction conditions and product analyses. Biochemistry. 1984 Aug 14;23(17):3934–3945. doi: 10.1021/bi00312a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson R. A., Kavanagh T. A., Bevan M. W. GUS fusions: beta-glucuronidase as a sensitive and versatile gene fusion marker in higher plants. EMBO J. 1987 Dec 20;6(13):3901–3907. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02730.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamakaka R. T., Thomas J. O. Chromatin structure of transcriptionally competent and repressed genes. EMBO J. 1990 Dec;9(12):3997–4006. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07621.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamoto T., Makino K., Orita S., Nakata A., Kakunaga T. DNA bending and binding factors of the human beta-actin promoter. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989 Jan 25;17(2):523–537. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.2.523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelleher R. J., 3rd, Flanagan P. M., Kornberg R. D. A novel mediator between activator proteins and the RNA polymerase II transcription apparatus. Cell. 1990 Jun 29;61(7):1209–1215. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90685-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee W., Haslinger A., Karin M., Tjian R. Activation of transcription by two factors that bind promoter and enhancer sequences of the human metallothionein gene and SV40. Nature. 1987 Jan 22;325(6102):368–372. doi: 10.1038/325368a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losa R., Omari S., Thoma F. Poly(dA).poly(dT) rich sequences are not sufficient to exclude nucleosome formation in a constitutive yeast promoter. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990 Jun 25;18(12):3495–3502. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.12.3495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lue N. F., Buchman A. R., Kornberg R. D. Activation of yeast RNA polymerase II transcription by a thymidine-rich upstream element in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989 Jan;86(2):486–490. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.2.486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxam A. M., Gilbert W. Sequencing end-labeled DNA with base-specific chemical cleavages. Methods Enzymol. 1980;65(1):499–560. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(80)65059-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElroy D., Blowers A. D., Jenes B., Wu R. Construction of expression vectors based on the rice actin 1 (Act1) 5' region for use in monocot transformation. Mol Gen Genet. 1991 Dec;231(1):150–160. doi: 10.1007/BF00293832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElroy D., Rothenberg M., Reece K. S., Wu R. Characterization of the rice (Oryza sativa) actin gene family. Plant Mol Biol. 1990 Aug;15(2):257–268. doi: 10.1007/BF00036912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElroy D., Rothenberg M., Wu R. Structural characterization of a rice actin gene. Plant Mol Biol. 1990 Feb;14(2):163–171. doi: 10.1007/BF00018557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElroy D., Zhang W., Cao J., Wu R. Isolation of an efficient actin promoter for use in rice transformation. Plant Cell. 1990 Feb;2(2):163–171. doi: 10.1105/tpc.2.2.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean B. G., Eubanks S., Meagher R. B. Tissue-specific expression of divergent actins in soybean root. Plant Cell. 1990 Apr;2(4):335–344. doi: 10.1105/tpc.2.4.335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meagher R. B. Divergence and differential expression of actin gene families in higher plants. Int Rev Cytol. 1991;125:139–163. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)61218-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miwa T., Kedes L. Duplicated CArG box domains have positive and mutually dependent regulatory roles in expression of the human alpha-cardiac actin gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1987 Aug;7(8):2803–2813. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.8.2803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muscat G. E., Gustafson T. A., Kedes L. A common factor regulates skeletal and cardiac alpha-actin gene transcription in muscle. Mol Cell Biol. 1988 Oct;8(10):4120–4133. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.10.4120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nairn C. J., Winesett L., Ferl R. J. Nucleotide sequence of an actin gene from Arabidopsis thaliana. Gene. 1988 May 30;65(2):247–257. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90461-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson L., Meagher R. B. Diverse soybean actin transcripts contain a large intron in the 5' untranslated leader: structural similarity to vertebrate muscle actin genes. Plant Mol Biol. 1990 Apr;14(4):513–526. doi: 10.1007/BF00027497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanger F., Nicklen S., Coulson A. R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1977 Dec;74(12):5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartorelli V., Webster K. A., Kedes L. Muscle-specific expression of the cardiac alpha-actin gene requires MyoD1, CArG-box binding factor, and Sp1. Genes Dev. 1990 Oct;4(10):1811–1822. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.10.1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauer F., Jäckle H. Concentration-dependent transcriptional activation or repression by Krüppel from a single binding site. Nature. 1991 Oct 10;353(6344):563–566. doi: 10.1038/353563a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlapp T., Rödel G. Transcription of two divergently transcribed yeast genes initiates at a common oligo(dA-dT) tract. Mol Gen Genet. 1990 Sep;223(3):438–442. doi: 10.1007/BF00264451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultes N. P., Szostak J. W. A poly(dA.dT) tract is a component of the recombination initiation site at the ARG4 locus in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1991 Jan;11(1):322–328. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.1.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen R. A., Goswami S. K., Mascareno E., Kumar A., Siddiqui M. A. Tissue-specific transcription of the cardiac myosin light-chain 2 gene is regulated by an upstream repressor element. Mol Cell Biol. 1991 Mar;11(3):1676–1685. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.3.1676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon M. J., Strauss F., Varshavsky A. A mammalian high mobility group protein recognizes any stretch of six A.T base pairs in duplex DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986 Mar;83(5):1276–1280. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.5.1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struhl K. Naturally occurring poly(dA-dT) sequences are upstream promoter elements for constitutive transcription in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985 Dec;82(24):8419–8423. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.24.8419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiry-Blaise L. M., Loppes R. Deletion analysis of the ARG4 promoter of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: a poly(dAdT) stretch involved in gene transcription. Mol Gen Genet. 1990 Sep;223(3):474–480. doi: 10.1007/BF00264456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster K. A., Kedes L. The c-fos cyclic AMP-responsive element conveys constitutive expression to a tissue-specific promoter. Mol Cell Biol. 1990 May;10(5):2402–2406. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.5.2402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter E., Varshavsky A. A DNA binding protein that recognizes oligo(dA).oligo(dT) tracts. EMBO J. 1989 Jun;8(6):1867–1877. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03583.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W., McElroy D., Wu R. Analysis of rice Act1 5' region activity in transgenic rice plants. Plant Cell. 1991 Nov;3(11):1155–1165. doi: 10.1105/tpc.3.11.1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Kries J. P., Buhrmester H., Strätling W. H. A matrix/scaffold attachment region binding protein: identification, purification, and mode of binding. Cell. 1991 Jan 11;64(1):123–135. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90214-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]