Abstract

Great progress has been made in understanding how immune cells detect microbial pathogens. An area that has received particular attention is nucleic acid sensing where RNA and DNA sensing machineries have been uncovered. For DNA, TLR9 in endosomes and numerous cytoplasmic DNA binding proteins have been identified. Several of these have been proposed to couple DNA recognition to induction of type I IFNs, pro-inflammatory cytokines and/or caspase-1 activation. Given the ubiquitous expression of many of these DNA binding proteins and the significant potential for endogenous DNA to engage these molecules, it is important that DNA recognition is tightly regulated. A better understanding of DNA recognition pathways can provide new insights into infectious, inflammatory and autoimmune diseases.

Introduction

The innate immune system discriminates between self, non-self and altered self [1]. Families of germline-encoded receptors monitor cellular compartments for non-self or altered self-molecules resulting from microbial infection or altered cellular homeostasis. These sensor systems (of which there are now many) collectively activate responses that contribute to the elimination of infectious pathogens. Sensors on the surface of cells such as Toll like receptor-4 (TLR-4) detect extracellular microbial products, while nucleic acid sensing TLRs sample microbial genomes exposed in the destructive acidic environment of the phagolysosomal compartment. Many pathogens, particularly those that replicate in the cytosol never encounter endosomal TLRs and as a consequence intracellular sensors have evolved to detect these pathogens. In this context, nucleic acid recognition systems, especially those that recognize DNA are at the forefront of cytoplasmic immune surveillance.

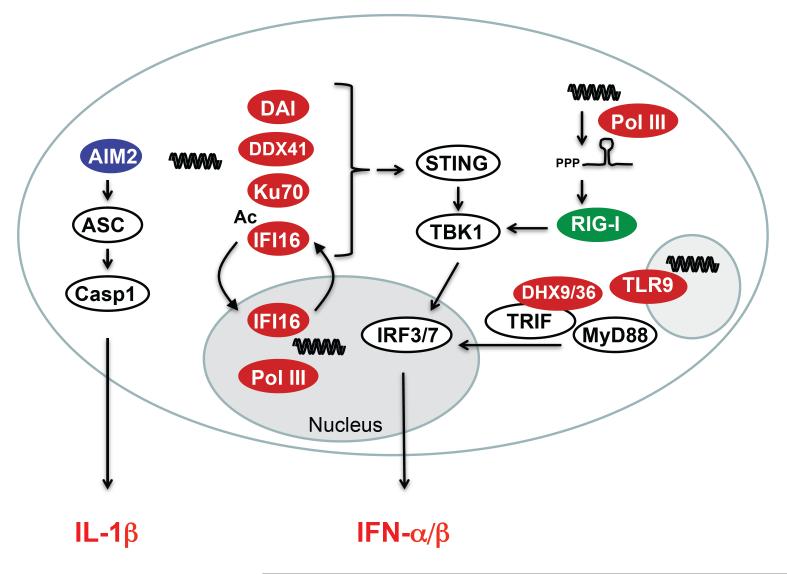

Normally DNA is packaged in the nucleus or mitochondria of eukaryotic cells. During infection or in response to a variety of stress signals, DNA may be exposed within the endosomal or cytoplasmic compartment where it leads to the induction of type I interferons (IFN), inflammatory cytokines and activation of caspase-1 [2,3] (Figure 1). The cytoplasmic location of DNA in this case serves as a danger signal to alert the innate immune system to the presence of the infectious agent [4,5]. The molecular mechanisms involved in the recognition of foreign DNA are being studied extensively. A number of DNA binding proteins have been identified and in some cases linked to aspects of the DNA driven inflammatory response (see below). In broad terms, the downstream responses activated by cytoplasmic DNA can be divided into two major pathways: activation of caspase-1 and activation of STING dependent signaling. Although progress in this area has been rapid, many aspects of the DNA dependent response are only beginning to be worked out.

Figure 1.

DNA is targeted in cytosolic, nucleic, and endosomal compartments with subsequent secretion of type I IFNs and pro-inflammatory cytokines. IFN responses are regulated through activation of the transcription factors IRF3 and -7. IRF3 is constitutively expressed in most cell types, whereas IRF7 is constitutively expressed only in pDCs. TLR9 depends on the adaptor MyD88, while DHX9 and DHX36 use MyD88 and TRIF as their adaptors. The cytosolic DNA sensors depend on the adaptor STING, which forms signaling platforms with TBK1 and possibly other signaling molecules, to activate IRF3/7. Secretion of the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1β depends on assembly of the multiprotein complex known as the inflammasome. Ligation of the cytosolic DNA sensor AIM2 leads to inflammasome activation with proteolytic cleavage of Casp1 and subsequent cleavage of pro-IL-1β into the highly inflammatory IL-1β.

Caspase-1 activation in response to cytoplasmic DNA and nuclear sensing of viral DNA

The best characterized DNA sensing pathway results in activation of caspase-1. Work from several labs including our own has shown that cytoplasmic DNA activates casapse-1, which in turn leads to the proteolytic processing of the inactive zymogens, pro-IL-1β and pro-IL18 [6-9*]. These cytokines act in a number of ways to enhance anti-microbial immunity. Cytoplasmic DNA activates caspase-1 via a multiprotein complex known as the inflammasome which catalyzes the conversion of pro-caspase 1 to active caspase 1 [10]. There are distinct types of inflammasomes, differentiated by their protein constituents, activators, and effectors. The best-studied DNA activated inflammasome contains AIM2, a member of a larger family of DNA binding proteins. Recent structural studies have shown that non-sequence-specific DNA recognition is accomplished through electrostatic attraction between positively charged HIN domain residues and the dsDNA sugar-phosphate backbone [11]. Normally, an intramolecular complex of the AIM2 Pyrin and HIN domain maintains AIM2 in an autoinhibited state. Cytoplasmic DNA liberates the Pyrin domain to engage with the adapter molecule ASC to form an inflammasome. AIM2 appears to be the predominant mechanism by which cytoplasmic DNA activates caspase-1, since cells from AIM2-deficient mice are largely unable to activate caspase-1 and control IL-1β and IL-18 production [10,12]. As a consequence AIM2-deficient mice are unable to control certain DNA viruses and cytoplasmic bacterial pathogens [10,12]. In addition to AIM2, the AIM2-related protein IFN-inducible protein 16 (IFI16), both of which are members of a larger family of DNA binding proteins also forms an inflammasome complex in the nucleus of Kaposi-sarcoma associated herpes virus (KSHV) infected endothelial cells. IFI16 and ASC associate within the nucleus and subsequently translocate to a perinuclear area to engage caspase-1[13].

Mitochondrial DNA which consists of a double-stranded 16.5 kb circular molecule attached to the inner mitochondrial membrane also activates caspase-1. MtDNA can be released into the cytosol in situations where mitophagy is impaired or dysfunctional. Damaged mitochondria accumulate and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) translocates to the cytosol [14,15]. Caspase-1 activation in this case is not dependent on AIM2, but instead is dependent on the NLRP3 inflammasome. Mitochondrial DNA is particularly prone to oxidative damage and oxidized mitochondrial DNA binds to NLRP3 directly [15].

STING: a central player in the cellular response to DNA

The second major pathway induced upon cytoplasmic DNA exposure results in transcriptional regulation of the type I IFNs, IFNα/β and IFN stimulated genes. IRF3 is critical for this transcriptional response. Although less well studied, NFκB and MAPKs are also activated upon cytoplasmic DNA signaling leading to transcription of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNFα. One molecule of key importance for this DNA-stimulated IFN and cytokine response is stimulator of IFN genes (STING) (also called Tmem173, MPYS, MITA) [16,17]. STING is a multi membrane-spanning protein that is located in the endoplasmic reticulum (and possibly the mitochondria). A hallmark of STING activation involves its movement from the endoplasmic reticulum (and possibly the mitochondria) to perinuclear punctate structures that are still poorly characterized. The C-terminal domain of STING, which protrudes into the cytoplasm provides a platform that directs TBK1 to phosphorylate and activate IRF3 [17,18]. STING also couples DNA recognition to NFκB and MAPK signaling, although the mediators involved have yet to be defined in detail. The importance of STING in DNA sensing is underscored by the finding that DNA induced responses are dramatically impaired in cells from STING-/- mice. STING is also critical for IFN production following infection with DNA viruses, cytosolic bacteria such as Listeria monocytogenes and the malaria-causing parasite Plasmodium falciparum [2,18,19]. STING-deficient mice are also highly susceptible to herpesvirus infections in vivo [16].

The discovery of new DNA binding proteins has attemplted to clarify the STING signaling pathway. ZBP1 (also called DAI [20]), IFI16 [21], a member of the AIM2 family and DDX41 [22], a member of a larger family of DDX molecules have all been identified as candidate DNA sensors. Of these, IFI16 and DDX41 have been shown to engage STING. DDX41 is expressed basally and localized in the cytosol. RNAi studies have shown that DDX41 controls DNA induced IFN signalling in DCs, while IFI16 a type I or type II IFN inducible gene has been linked to DNA signaling in macrophages and fibroblasts. IFI16 is predominantly nuclear in most cell types, however a small pool of IFI16 also exists in the cytoplasm of macrophages where it co-localizes with HSV DNA [21]. RNAi knockdown of IFI16 or of Ifi204, a member of the murine AIM2 like receptor (or PYHIN family) in murine macrophages both result in impaired IFN responses to HSV DNA and HSV-1 virus. Macrophages are not permissive to herpesviruses such as HSV1. In permissive cells such as fibroblasts, the HSV1 genome is delivered to the nucleus where it is detected by nuclear IFI16 [23,24]. Sensing of HSV1 in these cells is dependent on nuclear localized IFI16 and on cytoplasmic STING. STING-deficiency as well as siRNA knockdown of Ifi204 in vivo impair early control of corneal HSV-1 infection [25]. An additional compelling argument for the involvement of IFI16 in STING signaling during HSV-1 infection is the observation that ICP0, an immediate early HSV gene product with E3 ubuiquitin ligase activity targets IFI16 and Ifi204 for degradation by the proteasome [23].

Despite great progress in understanding the role of DDX41, IFI16 and STING, a unifying picture of how DNA signaling is initiated by these molecules and their importance in vivo is still lacking. The development of knockout mice for these type I IFN-inducing DNA sensors will likely clarify some of the outstanding issues. However, this may be more complex than has been observed for other PRRs, since DNA sensing pathways may differ in human and mouse cells. Mice have 14 ALR genes while human cells have only four [26,27] indicating that there may be considerable redundancy in these pathways in murine cells.

Additional roles of STING

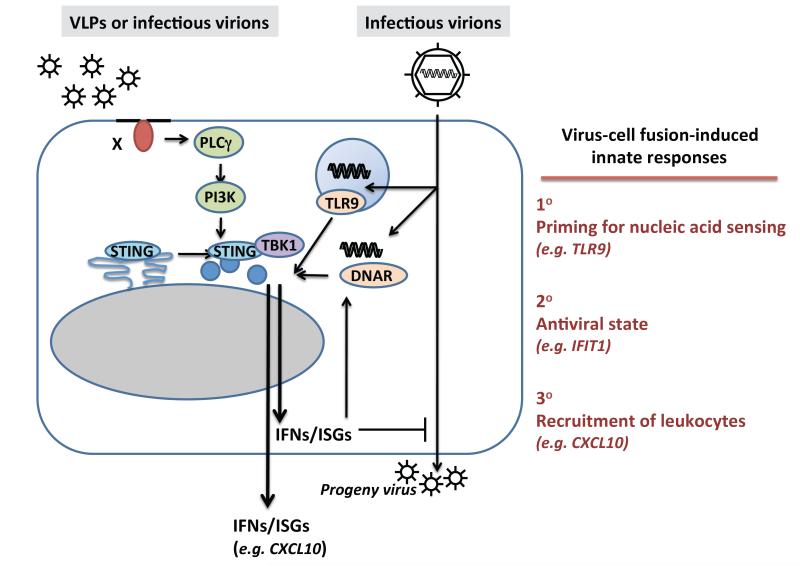

It is important to point out that STING has also been linked to some aspects of RNA sensing via RIG-I [17]. STING controls STAT-6 signaling and transcription of STAT6 dependent chemokines in both RNA and DNA sensing pathways [28]. Most recently, STING has been shown to act as a direct immune sensor for cyclic dinucleotides, bacterial second messengers that regulate bacterial motility and biofilm formation [29]. In this case, cyclic di-nucleotides bind to STING directly at the interphase between two monomers in the STING dimer [19,30-34]. This latter fuction of STING appears to be independent of “upstream DNA sensing molecules”. In addition to these functions of STING, antiviral responses evoked by membrane disturbance during virus-cell membrane fusion also requires STING [35] (Figure 2). Disturbance of cellular membranes upon virus-cell fusion induces re-localization of STING to signaling competent STING-TBK1 complexes in order to potentiate DNA sensing [35](Figure 2). This latter function of STING highlights additional roles for STING and cross-talk at the level of STING in multiple anti-viral immune pathways. Finally, additional studies have linked STING to MHC class II sigaling [36]. MHC class II-mediated cell death signaling requires STING-dependent activation of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase signaling pathway [16]. It is important therefore to consider these roles of STING when examining STING-deficient cells and animals.

Figure 2.

Disturbance of cellular membranes primes the cell to enhance DNA sensing. Fusion between viral envelopes and cellular membranes is sufficient to rearrange intracellular signaling molecules such as STING and TBK1 and to induce low-grade type I IFN responses and secretion of CXCL10. Detection of this disturbance of the cellular membrane primes the cell to improve the detection of incoming virus. In fact, priming of cells by fusion increases the sensitivity to DNA. The priming might therefore improve immunity to infection by 1) Improving sensing of incoming PRR ligands, 2) Inducing an anti-viral state in the targeted cell, and 3) Initiating the recruitment of nearby leukocytes.

DNA recognition and disease

Given the apparent ubiquitous presence of nucleic acid receptors, and their potential for causing inflammation, it is not surprising that a number of DNases, localized to various cellular compartments, effectively limit the activation of these receptors by endogenous ligands. Their importance has become increasingly apparent as defects in DNase I, II and III have all been linked to the pathogenesis of a variety of autoimmune diseases. Defects in DNaseI are associated with SLE [37] [38], while those in DNase II result in lethal anemia and a progressive polyarthritis. Defects in DNaseIII (also called TREX1) are linked to Aicardi Goutieres syndrome and Chilbain lupus in humans [39,40]. Trex1 prevents the accumulation of cytoplasmic DNA derived from endogenous retroelements and Trex-1-deficient mice develope myocarditis [41,42]. Although the sensor for cytosolic DNA in Trex1-deficient cells has not been identified, it was recently reported that myocarditis in Trex1-/- mice was prevented in Trex1-/-STING-/- DKO mice. These observations indicate that Trex1 is a negative regulator of STING signaling. It will be interesting to learn which DNA sensors recognize Trex1-degradable DNA and also whether this system interacts with other innate systems to amplify and precipitate disease in individuals lacking Trex1 function.

Conclusion

Clearly great progress has been made in understanding how DNA induces inflammatory responses, studies that have provided new insights into infectious and autoimmune diseases. Characterization of these DNA sensing pathways and the counter regulatory mechanisms that prevent their uncontrolled activation continue to help us build a framework for understanding host-defenses and the molecular basis of self/non-self discrimination. Future discoveries in this area will likely unveil new opportunities for therapeutic interventions in infectious and autoimmune disease.

Highlights: Current Opinion in Immunology.

DNA recognition in health and disease.

DNA sensing is a major means of pathogen detection.

TLR9 and multiple cytoplasmic proteins detect DNA.

DNA activates caspase-1 activating inflammasome.

STING signaling is a major hub of DNA sensing.

DNase limit activation of DNA sensors by endogenous ligands.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by grants from the NIH (AI067497 and AI093752) to K.A.Ffrom the Danish Medical Research Council (09-072636 and 12-124330), the Novo Nordisk Foundation, The Velux Foundation, The Lundbeck Foundation (R34-3855 and R83-A7598), Elvira og Rasmus Riisforts almenvelgørende Fond and Fonden til Lægevidenskabens Fremme (all S.R.P).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Takeuchi O, Akira S. Innate immunity to virus infection. Immunol Rev. 2009;227:75–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00737.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharma S, DeOliveira RB, Kalantari P, Parroche P, Goutagny N, Jiang Z, Chan J, Bartholomeu DC, Lauw F, Hall JP, et al. Innate immune recognition of an AT-rich stem-loop DNA motif in the Plasmodium falciparum genome. Immunity. 2011;35:194–207. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sharma S, Fitzgerald KA. Innate immune sensing of DNA. PLoS pathogens. 2011;7:e1001310. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stetson DB, Medzhitov R. Recognition of cytosolic DNA activates an IRF3-dependent innate immune response. Immunity. 2006;24:93–103. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ishii KJ, Coban C, Kato H, Takahashi K, Torii Y, Takeshita F, Ludwig H, Sutter G, Suzuki K, Hemmi H, et al. A Toll-like receptor-independent antiviral response induced by double-stranded B-form DNA. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:40–48. doi: 10.1038/ni1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6*.References 6-9 are of particular interest: (These studies identified the PYHIN protein AIM2 as a critical sensor for cytoplasmic DNA that couples DNA recognition to caspase-1 activation). Hornung V, Ablasser A, Charrel-Dennis M, Bauernfeind F, Horvath G, Caffrey DR, Latz E, Fitzgerald KA. AIM2 recognizes cytosolic dsDNA and forms a caspase-1-activating inflammasome with ASC. Nature. 2009;458:514–518. doi: 10.1038/nature07725.

- 7*.Fernandes-Alnemri T, Yu JW, Datta P, Wu J, Alnemri ES. AIM2 activates the inflammasome and cell death in response to cytoplasmic DNA. Nature. 2009 doi: 10.1038/nature07710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8*.Burckstummer T, Baumann C, Bluml S, Dixit E, Durnberger G, Jahn H, Planyavsky M, Bilban M, Colinge J, Bennett KL, et al. An orthogonal proteomic-genomic screen identifies AIM2 as a cytoplasmic DNA sensor for the inflammasome. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:266–272. doi: 10.1038/ni.1702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9*.Roberts TL, Idris A, Dunn JA, Kelly GM, Burnton CM, Hodgson S, Hardy LL, Garceau V, Sweet MJ, Ross IL, et al. HIN-200 proteins regulate caspase activation in response to foreign cytoplasmic DNA. Science. 2009;323:1057–1060. doi: 10.1126/science.1169841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rathinam VA, Jiang Z, Waggoner SN, Sharma S, Cole LE, Waggoner L, Vanaja SK, Monks BG, Ganesan S, Latz E, et al. The AIM2 inflammasome is essential for host defense against cytosolic bacteria and DNA viruses. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:395–402. doi: 10.1038/ni.1864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11*.References 11 is of particular interest: (this study demonstrated that AIM2 and IFI16 bind dsDNA in a sequence independent manner through electrostatic interactions). Jin T, Perry A, Jiang J, Smith P, Curry JA, Unterholzner L, Jiang Z, Horvath G, Rathinam VA, Johnstone RW, et al. Structures of the HIN domain:DNA complexes reveal ligand binding and activation mechanisms of the AIM2 inflammasome and IFI16 receptor. Immunity. 2012;36:561–571. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.02.014.

- 12.Fernandes-Alnemri T, Yu JW, Juliana C, Solorzano L, Kang S, Wu J, Datta P, McCormick M, Huang L, McDermott E, et al. The AIM2 inflammasome is critical for innate immunity to Francisella tularensis. Nature immunology. 2010;11:385–393. doi: 10.1038/ni.1859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kerur N, Veettil MV, Sharma-Walia N, Bottero V, Sadagopan S, Otageri P, Chandran B. IFI16 acts as a nuclear pathogen sensor to induce the inflammasome in response to Kaposi Sarcoma-associated herpesvirus infection. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;9:363–375. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14*.References 14 and 15 are of particular interest: (These references demonstrated that autophagy normally curbs inflammasome activation by removal of damaged mitochondria which release DNA leading to activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome). Nakahira K, Haspel JA, Rathinam VA, Lee SJ, Dolinay T, Lam HC, Englert JA, Rabinovitch M, Cernadas M, Kim HP, et al. Autophagy proteins regulate innate immune responses by inhibiting the release of mitochondrial DNA mediated by the NALP3 inflammasome. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:222–230. doi: 10.1038/ni.1980.

- 15*.Shimada K, Crother TR, Karlin J, Dagvadorj J, Chiba N, Chen S, Ramanujan VK, Wolf AJ, Vergnes L, Ojcius DM, et al. Oxidized mitochondrial DNA activates the NLRP3 inflammasome during apoptosis. Immunity. 2012;36:401–414. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16*.References 16-19 are of particular interest: (These studies identified STING as a critical mediator of DNA signaling and an important component of the host-response to herpesviruses and cytosolic bacteria). Ishikawa H, Ma Z, Barber GN. STING regulates intracellular DNA-mediated, type I interferon-dependent innate immunity. Nature. 2009;461:788–792. doi: 10.1038/nature08476.

- 17*.Ishikawa H, Barber GN. STING is an endoplasmic reticulum adaptor that facilitates innate immune signalling. Nature. 2008;455:674–678. doi: 10.1038/nature07317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ishikawa H, Barber GN. The STING pathway and regulation of innate immune signaling in response to DNA pathogens. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0605-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19*.Sauer JD, Sotelo-Troha K, von Moltke J, Monroe KM, Rae CS, Brubaker SW, Hyodo M, Hayakawa Y, Woodward JJ, Portnoy DA, et al. The N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea-induced Goldenticket mouse mutant reveals an essential function of Sting in the in vivo interferon response to Listeria monocytogenes and cyclic dinucleotides. Infect Immun. 2011;79:688–694. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00999-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takaoka A, Wang Z, Choi MK, Yanai H, Negishi H, Ban T, Lu Y, Miyagishi M, Kodama T, Honda K, et al. DAI (DLM-1/ZBP1) is a cytosolic DNA sensor and an activator of innate immune response. Nature. 2007;448:501–505. doi: 10.1038/nature06013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21*.References 21022 are of particular interest: (These references identified IFI16 and DDX41 as DNA PRRs). Unterholzner L, Keating SE, Baran M, Horan KA, Jensen SB, Sharma S, Sirois CM, Jin T, Latz E, Xiao TS, et al. IFI16 is an innate immune sensor for intracellular DNA. Nat Immunol. 2010 doi: 10.1038/ni.1932.

- 22*.Zhang Z, Yuan B, Bao M, Lu N, Kim T, Liu YJ. The helicase DDX41 senses intracellular DNA mediated by the adaptor STING in dendritic cells. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:959–965. doi: 10.1038/ni.2091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Orzalli MH, Deluca NA, Knipe DM. Nuclear IFI16 induction of IRF-3 signaling during herpesviral infection and degradation of IFI16 by the viral ICP0 protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211302109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li T, Diner BA, Chen J, Cristea IM. Acetylation modulates cellular distribution and DNA sensing ability of interferon-inducible protein IFI16. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:10558–10563. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203447109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Conrady CD, Zheng M, Fitzgerald KA, Liu C, Carr DJ. Resistance to HSV-1 infection in the epithelium resides with the novel innate sensor, IFI-16. Mucosal Immunol. 2012;5:173–183. doi: 10.1038/mi.2011.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schattgen SA, Fitzgerald KA. The PYHIN protein family as mediators of host defenses. Immunol Rev. 2011;243:109–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cridland JA, Curley EZ, Wykes MN, Schroder K, Sweet MJ, Roberts TL, Ragan MA, Kassahn KS, Stacey KJ. The mammalian PYHIN gene family: Phylogeny, evolution and expression. BMC Evol Biol. 2012;12:140. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-12-140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen H, Sun H, You F, Sun W, Zhou X, Chen L, Yang J, Wang Y, Tang H, Guan Y, et al. Activation of STAT6 by STING is critical for antiviral innate immunity. Cell. 2011;147:436–446. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.References 29-34 are of particular interest: (they demonstrated that bacterial second messengers bind directly to STING to activate downstream signaling, establishing STING as not only an adapter molecule but also a sensor in its own right). Burdette DL, Monroe KM, Sotelo-Troha K, Iwig JS, Eckert B, Hyodo M, Hayakawa Y, Vance RE. STING is a direct innate immune sensor of cyclic di-GMP. Nature. 2011;478:515–518. doi: 10.1038/nature10429.

- 30.Shang G, Zhu D, Li N, Zhang J, Zhu C, Lu D, Liu C, Yu Q, Zhao Y, Xu S, et al. Crystal structures of STING protein reveal basis for recognition of cyclic di-GMP. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19:725–727. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ouyang S, Song X, Wang Y, Ru H, Shaw N, Jiang Y, Niu F, Zhu Y, Qiu W, Parvatiyar K, et al. Structural analysis of the STING adaptor protein reveals a hydrophobic dimer interface and mode of cyclic di-GMP binding. Immunity. 2012;36:1073–1086. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shu C, Yi G, Watts T, Kao CC, Li P. Structure of STING bound to cyclic di-GMP reveals the mechanism of cyclic dinucleotide recognition by the immune system. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19:722–724. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Su YC, Tu ZL, Yang CY, Chin KH, Chuah ML, Liang ZX, Chou SH. Crystallization studies of the murine c-di-GMP sensor protein STING. Acta Crystallogr Sect F Struct Biol Cryst Commun. 2012;68:906–910. doi: 10.1107/S1744309112024372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yin Q, Tian Y, Kabaleeswaran V, Jiang X, Tu D, Eck MJ, Chen ZJ, Wu H. Cyclic di-GMP sensing via the innate immune signaling protein STING. Mol Cell. 2012;46:735–745. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.05.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.References 35 is of particular interest: (This study demonstrated that STING can also function in DNA-independent signaling pathways to prime the anti-viral response). Holm CK, Jensen SB, Jakobsen MR, Cheshenko N, Horan KA, Moeller HB, Gonzalez-Dosal R, Rasmussen SB, Christensen MH, Yarovinsky TO, et al. Virus-cell fusion as a trigger of innate immunity dependent on the adaptor STING. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:737–743. doi: 10.1038/ni.2350.

- 36.Jin L, Waterman PM, Jonscher KR, Short CM, Reisdorph NA, Cambier JC. MPYS, a novel membrane tetraspanner, is associated with major histocompatibility complex class II and mediates transduction of apoptotic signals. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:5014–5026. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00640-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tao K, Yasutomo K. [SLE caused by DNase 1 gene mutation] Nihon Rinsho. 2005;63(Suppl 5):205–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Napirei M, Gultekin A, Kloeckl T, Moroy T, Frostegard J, Mannherz HG. Systemic lupuserythematosus: deoxyribonuclease 1 in necrotic chromatin disposal. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2006;38:297–306. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Crow YJ, Rehwinkel J. Aicardi-Goutieres syndrome and related phenotypes: linking nucleic acid metabolism with autoimmunity. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:R130–136. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Crow YJ, Hayward BE, Parmar R, Robins P, Leitch A, Ali M, Black DN, van Bokhoven H, Brunner HG, Hamel BC, et al. Mutations in the gene encoding the 3′-5′ DNA exonuclease TREX1 cause Aicardi-Goutieres syndrome at the AGS1 locus. Nat Genet. 2006;38:917–920. doi: 10.1038/ng1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gall A, Treuting P, Elkon KB, Loo YM, Gale M, Jr., Barber GN, Stetson DB. Autoimmunity initiates in nonhematopoietic cells and progresses via lymphocytes in an interferon-dependent autoimmune disease. Immunity. 2012;36:120–131. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42*.References 42 is of particular interest: (It demonstrated that accumulation of DNA from endogenous retroelements could activate cytosolic inflammatory pathways leading to autoimmunity). Stetson DB, Ko JS, Heidmann T, Medzhitov R. Trex1 prevents cell-intrinsic initiation of autoimmunity. Cell. 2008;134:587–598. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.032.