Abstract

Objective

While many patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) experience psychological problems, such as depression, benefit-finding is commonly reported. Using the Broaden-and-Build Model of positive emotions (Fredrickson, 2001) and the Expectancy-Value Model of optimism (Carver & Scheier, 1998) as two related, yet, distinct conceptual frameworks, this study examined positive affect and optimism as mediators of the relationship between improved depression and enhanced benefit-finding.

Design

MS patients (N = 127), who participated in a larger, randomized clinical trial comparing two types of telephone psychotherapy for depression, were assessed at baseline, midtherapy (8 weeks), end of therapy (16 weeks), and 6- and 12-month posttherapy.

Main Outcome Measures

Depression was measured with a telephone administered version of the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; Positive Affect was measured with the Positive Affect Subscale from the Positive and Negative Affect Scale; Optimism was measured with the Life Orientation Test—Revised; Benefit-Finding was measured with the revised version of the Stress-Related Growth Scale.

Results

Data were analyzed with multilevel random-effects models, controlling for time since MS diagnosis and type of treatment. Improved depression was associated with increased benefit-finding over time. The relationship between improved depression and benefit-finding was significantly mediated by both increased optimism and increased positive affect.

Conclusion

Findings provide support to both theoretical models. Positivity appears to promote benefit-finding in MS.

Keywords: multiple sclerosis, benefit-finding, depression, optimism, positive affect

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a degenerative neurological disease that can severely impair patients' physical functioning, cognition, activity, and energy levels. Depression is common in MS and affects anywhere from 15% to 47% of patients (Chwastiak et al., 2002; Patten, Beck, Williams, Barbui, & Metz, 2003), with lifetime prevalence estimates at 50% (Sadovnick, 1991). Twenty-five percent of MS patients are reported to have unrecognized and untreated depression (McGuigan & Hutchinson, 2006). A shortcoming of psychosocial research on MS patients is that it has largely examined only the negative consequences of MS, focusing on the pain and suffering brought about by the disease. While it is clear that many MS patients do experience depression and disability, patients also frequently report finding benefits in having MS. Benefit-finding, both for MS patients as well as other chronically ill individuals, is considered a marker of successful adaptation to the disease.

Mohr and colleagues (Mohr et al., 1999) were the first to publish that MS patients frequently report benefit-finding, defined as the positive changes brought about by MS. Similarly, Pakenham (2005a) found that MS patients as well as their caregivers (2005b) commonly found benefits in the MS experience, such as feeling closer to their families and gaining an enhanced appreciation of life. Many studies have been published on depression and psychological distress in MS (e.g., Janssens et al., 2004; Solari, Ferrari, & Radice, 2006); however, data are less abundant on benefit-finding in MS. Given the scant data on benefit-finding in MS, we examined the growing literature on benefit-finding in chronic illness.

Although depression and benefit-finding appear to be common in chronic-illness, their empirical relationship to each other has not been well-understood due to inconsistent findings in the extant literature. A recent meta-analytic review of the relationship between benefit-finding and mental health indices reported greater benefit-finding was significantly related to lower levels of depression but was unrelated to measures of global distress (Helgeson, Reynolds, & Tomich, 2006). The authors suggested that measures of global distress do not distinguish well among indices of negative mood, such as depression, and that researchers should focus on benefit-finding with specific mental health outcomes. While several studies do show a relationship between benefit-finding and depression (see Helgeson et al., 2006, for a review), little research has examined the relationship between these two variables where depression was manipulated, such as in a psychotherapy trial. One study (Antoni et al., 2001; McGregor et al., 2004) reported that a 10-week cognitive–behavioral stress management (CBSM) group produced greater benefit-finding among women who were recently treated for early stage breast cancer, compared to a no-therapy control-group. Women who received CBSM also reported lower depression scores than the control condition. While that intervention was designed to help women cope with breast cancer-related issues and not specifically to decrease depression or increase benefit-finding, the findings suggest that treatment for depression may enhance benefit-finding.

We considered two related but conceptually distinct theoretical models of psychological adaptation—the Broaden-and-Build Model and the Expectancy-Value Model—to elucidate the relationship between depression and benefit-finding in chronic illness. First, we examined Barbara Fredrickson's Broaden-and-Build Model (Fredrickson, 2001). According to the Broaden-and-Build Model, positivity (e.g., positive affect, hope, curiosity) promotes resilience in the face of adversity. Negative emotions, such as depression, serve to restrict one's ability to grow; positivity serves to promote approach and exploration and to “broaden” one's mindset and perspectives. Therefore, the theory would lead to the hypothesis that improvements in depression are likely to lead to increased positivity, which should encourage subsequent psychological growth.

Within the Broaden-and-Build framework, positive affect may be one mechanism by which depression affects benefit-finding. While Fredrickson has not yet empirically examined benefit-finding as an outcome of positive emotions, her theory generalizes well to benefit-finding in chronic illness. Researchers have documented that positive affect is predictive of higher levels of benefit finding in MS patients (Pakenham, 2005a), breast cancer patients (Antoni et al., 2001; Sears, Stanton, & Danoff-Burg, 2003), and lupus patients (Katz, Flasher, Cacciapaglia, & Nelson, 2001). Furthermore, our own research has shown that improvements in depression after psychotherapy are associated with improved positive affect in MS patients (Hart, Fonareva, Merluzzi, & Mohr, 2005; Mohr et al., 2005). Therefore, we were interested whether increased positive affect mediated the relationship between improved depression and greater levels of benefit-finding in MS patients treated for depression.

The second model of psychological adaptation we examined was the Expectancy-Value Model (Carver & Scheier, 1998, 2003). In the context of the Expectancy-Value Model, optimism is a key cognitive mechanism by which individuals structure their behavior to achieve their goals (Scheier & Carver, 1992). Optimism has been defined as “the global expectation that good things will be plentiful in the future and bad things, scarce” (Peterson, 2000). These global positive expectancies are considered a major determinant of whether people continue to pursue valued life goals against the backdrop of chronic illness. An important component of benefit-finding is engaging in goals to overcome adversity (Siegel & Schrimshaw, 2000). However, a deficiency of positive expectancies, perhaps brought on by depression, may thwart efforts to find benefit in MS patients. This idea is supported by the larger literature on optimism, which advocates the idea that as depression improves, optimism increases (Seligman et al., 1988). Therefore, we posited that increased optimism would mediate the relationship between improved depression and greater benefit-finding in MS patients treated for depression.

Previous research has found benefit-finding and optimism to be positively related in cancer patients (Antoni et al., 2001; Sears et al., 2003; Urcuyo, Carver, & Antoni, 2005) and HIV/AIDS patients (Davis, Nolen-Hoesksema, & Larson, 1998; Milam, 2004). In Antoni and colleagues (2001) CBSM study, women lower in optimism (vs. higher) were more likely to report significantly higher levels of benefit-finding postintervention. While the relationship between benefit-finding and depression was not examined, women lower in optimism were also more likely to meet criterion for depression at baseline. These findings suggest that a psychotherapeutic intervention has the potential to increase benefit-finding, and one important link may be through decreasing depression and increasing optimism. However, this idea has yet to be empirically tested.

The main goal of this study was to examine the application of the Broaden-and-Build and Expectancy-Value models to the relationship of depression and benefit-finding in MS. We hypothesized that treatment for depression would lead to increases in both positive emotions (i.e., positive affect) and positive cognitions (i.e., optimistic expectancies), that would, in turn, enhance benefit-finding. Therefore, these theories, while conceptually distinct, are complementary to one another and were anticipated to facilitate understanding of at least two of the mechanisms by which improved depression is associated with increased benefit-finding after telephone-administered therapy for depression in MS patients.

Method

This study presents data obtained from a larger randomized clinical trial, which compared the efficacy of two telephone-administered psychotherapies in the treatment of depression in MS patients. The main outcome analyses showed both telephone-administered cognitive– behavioral therapy (T-CBT) and telephone-administered supportive emotion-focused therapy (T-SEFT) produced clinically significant decreases in depression, as reported in Mohr et al. (2005). In addition to demonstrating the efficacy of telephone-administered psychotherapy for treating depression, we have conducted a meta-analysis of psychotherapy administered over the telephone to treat depression (Mohr, Vella, Hart, Heckman, & Simon, in press). Our meta-analysis showed a pretreatment to posttreatment effect size of 0.82 for telephone-administered psychotherapy, which compares favorably with meta-analyses of face-to-face psychotherapy for depression.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

To be included in the study, patients were required to have (1) a MS diagnosis confirmed by the treating neurologist, (2) a functional impairment resulting in activity limitations as measured by a score of at least three out of a total possible score of six (indicating marked impact on activity) on one or more areas of functioning on Guy's Neurological Disability Scale (Sharrack & Hughes, 1999), (3) a score of 16 or above on the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and 14 or above on the Hamilton Rating Scale of Depression (HRSD), and (4) an ability to speak and read English, and (5) an age over 18 years. Patients were excluded if they (1) met criteria for dementia; (2) were currently in psychotherapy; (3) showed severe psychopathology including psychosis, current substance abuse, plan and intent to commit suicide; 4) were currently experiencing a MS exacerbation, (5) reported physical impairments preventing study participation, such as an inability to speak, read, or write; and (6) reported using medications that affect mood (e.g., steroidal anti-inflammatories). Use of antidepressant medications was not exclusionary.

Recruitment

Patients were recruited through Kaiser Permanente Medical Care Group of Northern California (KP) and regional chapters of the National Multiple Sclerosis Society (NMSS). Within KP, patients with MS were identified through the KP database. Subsequent to approval by their neurologists, letters were sent to patients inviting them to participate and asking that they return a stamped postcard if they did not wish to be contacted further. Patients who did not return the postcards after 10 days were contacted with a follow-up phone call. Interested patients received a description of the study and a brief telephone screen, assessing the level of depression symptoms and several exclusion criteria, was conducted. Patients who met the initial screening inclusion criteria qualified for a longer eligibility assessment, which evaluated all study inclusion and exclusion criteria. The consent process, approved by the UCSF and KP Human Subjects Review Committees, included initial verbal consent conducted by telephone. Following the verbal consent procedures, written consent was also obtained from the patient via U.S. mail.

Recruitment through regional NMSS chapters was initiated via announcements in NMSS chapter newsletters. Interested patients phoned a toll-free number and received a description of the study and the brief telephone screen as described above. The consent procedures were identical to those for KP patients, but the patient was also mailed a release of medical information. After the signed consent and release of medical information were received, study staff members confirmed the MS diagnosis with the patient's neurologist.

Assessments

All self-report materials were mailed to participants with stamped, addressed return envelopes. Interview assessments were conducted over the telephone. Participants were asked to complete self-report measures on the same day as the telephone assessment. Participants were paid $10.00 to $50.00 per assessment, depending on the time point and the length of the assessment. Telephone interview assessments were all audiotaped and conducted by trained clinical evaluators, who were blinded to treatment assignment. To calibrate and maintain reliability on the interview measures, each evaluator corated a tape once monthly. Assessments occurred at baseline, midtreatment (week 8), posttreatment (week 16), 6-month posttreatment (week 40), and 1-year posttreatment (week 64).

Measures

Patients completed all measures by self-report, with the exception of the HRSD, which was conducted by telephone interview.

Optimism

Generalized optimism was measured by the Life Orientation Test—Revised (LOT-R, Scheier, Carver, & Bridges, 1994). The LOT-R is comprised of six items, such as “In uncertain times, I expect the best,” and is rated on a 4-item Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (I agree a lot) to 4 (I disagree a lot). Internal consistencies were good across the course of the study (α = .83-.89)

Positive affect

Positive affect was measured with the 10-item positive affect scale from the Positive and Negative Affect Scale (PANAS; Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988). Each item is rated on a 5-item Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). Internal consistencies were excellent over the course of the study (α = .84-.92)

Benefit-finding

Benefit-finding was measured with the revised version of the Stress Related Growth Scale (Armeli, Gunthert, & Cohen, 2001). The 20-item measure asks participants, “To what extent has each of the following changed as a result of having MS?” Items include “My belief in how strong I am,” “treating others nicely,” and “being myself and not what others want me to be.” Each item is rated on 7-item Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (greatly decreased) to 7 (greatly increased). We conducted a principal-components analysis followed by an oblique rotation on all items. The factor analysis and corresponding scree plot suggested two significant factors; one consistent with “general benefit-finding” and the other consistent with “negative affect regulation.” The “negative affect regulation scale” had only three items, which had an unacceptably low internal consistency of α = .53. Therefore, we retained the unidimensional scale, which demonstrated excellent internal consistencies over the course of the study (α = .88–.94).

Depression

Depression was assessed with a telephone administered version of the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (Hamilton, 1960). The telephone version of the HRSD was developed and validated for use with the Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) version of the HRSD (Potts, Daniels, Burnam, & Wells, 1990). HRSD raters received training that involved listening to and rating previous tapes and engaging in mock interviews. Interrater reliability from monthly reliability checks, using interclass correlations, averaged 0.89 (range = 0.75–0.97). Internal consistencies across the course of the study were acceptable (α = .76–.78). While patients also completed the BDI at each study assessment, we selected the HRSD for use in the current study as it provided a more conservative estimate of depression.

Treatments and Clinicians

Participants were randomized to one of two 16-week telephone administered psychotherapies, T-CBT or T-SEFT. Individual sessions were conducted by Ph.D. level psychologists, who spoke to participants for 50-min each week. Randomization was stratified based upon whether the participant had a current DSM–IV diagnosis of major depression and current use of antidepressant medication.

T-CBT

T-CBT is a structured cognitive–behavioral therapy based on standard CBT for depression (Beck, 1995). We have developed a patient workbook that guides treatment (Mohr, Boudewyn, Goodkin, Bostrom, & Epstein, 2001; Mohr et al., 2000). The goal of T-CBT is to teach participants skills to manage their depressive cognitions and behaviors, as well as their life stressors and MS symptoms.

T-SEFT

T-SEFT is an adaptation of Greenberg, Rice and Elliott's manual for process-experiential psychotherapy (Greenberg, 2002). The goal of T-SEFT was to increase participants' level of experience of their internal world versus specific CBT skills management. The specific components of each therapy modality and therapist adherence to treatment models have been described previously (Mohr et al., 2005).

Data Analysis

All analyses were conducted on intent to treat basis. Initial analysis compared baseline demographics between treatment groups, using t tests for continuous data and chi-square (χ2) analyses for categorical data. All hypotheses were tested using multilevel random coefficient modeling, using restricted maximum likelihood methods, which has the advantage of handling participants with some degree of nonrandom missing time points. Each model contained the intercept as a random effect and utilized the unstructured covariance structure, as it was determined to provide the best fit of the possible within-participant error covariance structures. All multilevel random coefficient models were estimated using PROC MIXED in SAS, version 8.2 (SAS, 2001).

To establish mediation, the strength of the relationship between the predictor variable and outcome variable must be less when the mediator is entered in the model, compared to the strength of the relationship between the predictor and outcome variable without the mediator (Baron & Kenny, 1986; Kraemer, Stice, Kazdin, Offord, & Kupfer, 2001). To evaluate further the significance of the indirect (i.e., mediator) effects, we used a bootstrap procedure (Mallinckrodt, Abraham, Wei, & Russell, 2006) instead of the Sobel test (Sobel, 1982) described in Baron and Kenny (1986), which computes a Z statistic to test the significance of the indirect effect. The Sobel test tends to lack power with smaller effect sizes and is limited by the assumption of a normally distributed indirect effect and standard error, while the bootstrap approach has been shown to perform better across varying sample sizes and effect sizes (MacKinnon, Lockwood, & Williams, 2004).

The bootstrap procedure provides an estimate of the indirect effect and calculates a confidence interval for the point estimate (Mallinckrodt et al., 2006). The approach draws a large number of random samples with continuous replacement and computes the indirect effect a parameter for each sample. As suggested by Mallinckrodt et al. (2006), we calculated the estimate of the indirect effect based on 10000 bootstrap iterations by running an SPSS macro created by Preacher and Hayes (2004). In short, the point estimate is the mean indirect effect computed over 10000 samples, and the estimated standard error is the standard deviation of the 10000 estimates. A 95% confidence interval (CI) is calculated for the point estimate.

To analyze mediated relationships, lagged associations between depression and benefit-finding were examined. Depression, optimism, positive affect, and benefit-finding were each measured five times over the course of the study: baseline, 8 weeks, 16 weeks (end of therapy), 40 weeks (6 months after end of therapy), and 64 weeks (1 year after end of therapy). Each multilevel model contained two nested models. The first model entered effects for the intercept, time the covariates of time since MS diagnosis and type of therapy received (T-CBT vs. T-SEFT), and the lagged effect for depression. The second model then added the lagged mediators for optimism and positive affect.

Results

Sample

Of the 748 patients who completed the initial telephone screening, 223 met preliminary inclusion criteria for a full eligibility assessment. Of those, 150 were found eligible for randomization. Twenty-three of the 150 (15.3%) refused randomization. Sixty-two patients of the remaining 127 were randomized to T-CBT, and 65 patients were randomized to T-SEFT.

Table 1 displays descriptive statistics for the sample demographic and medical variables. As none of the baseline demographic or medical variables were significantly associated with treatment assignment (see Mohr et al., 2005), we have presented descriptive information for the sample as a whole. With the exception of greater time since receiving a MS diagnosis, none of the baseline demographic or medical variables showed a significant bivariate relationship with benefit-finding at any of the follow-up assessments.

Table 1. Sample Demographics and Medical Characteristics at Baseline (N = 127).

| Variable | Percent | M (years) | SD (years) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 48.0 | 9.8 | |

| Education | 15.4 | 2.6 | |

| Time since MS diagnosis | 11.2 | 10.0 | |

| Type of MS | |||

| Relapsing type | 89.0 | ||

| Nonrelapsing type | 10.2 | ||

| Gender | |||

| Male | 22.7 | ||

| Female | 77.3 | ||

| Marital status | |||

| Married/partnered | 61.8 | ||

| Single | 11.7 | ||

| Separated/divorced | 21.9 | ||

| Widowed | 4.7 | ||

| Ethnicity | |||

| Caucasian | 89.1 | ||

| African American | 4.7 | ||

| Latino/a | 2.3 | ||

| Native American | 1.6 | ||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0.8 | ||

| Other | 1.6 |

Attrition

Seven participants did not complete the 16 weeks of treatment (5.5%; 3 T-CBT and 4 T-SEFT). Of these, five agreed to continue with follow-up assessments (2 T-CBT and 3 T-SEFT), while two dropped out of both treatment and assessments (1 T-CBT and 1 T-SEFT, 1.6%). No significant differences were found on any of the demographic or key study variables for completers versus noncompleters of the treatment.

Preliminary Analyses

Table 2 presents the fixed effects for time over the course of the study (from baseline to 1-year posttreatment) for benefit-finding, depression, optimism, and positive affect. Random-effect models showed that benefit-finding, optimism, positive affect all increased significantly from baseline to the final study assessment point. Furthermore, baseline values of depression significantly decreased over the course of the study.

Table 2. Fixed Effects for Time on Key Study Variables, Adjusted for Years Since MS Diagnosis and Type of Therapy Received.

| Variable | Intercept | SE | Estimate for time | SE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benefit-finding | 73.40* | 2.46 | 0.20* | 0.03 |

| Depression | 19.64* | 0.70 | −0.11* | 0.01 |

| Optimism | 16.27* | 0.68 | 0.03* | 0.01 |

| Positive affect | 22.66* | 0.96 | 0.06* | 0.01 |

p < .0001.

Depression and Benefit-Finding

We initially sought to examine the relationship between depression, the mediators (positive affect and optimism) and benefit-finding with each lagged in time. First, the data were structured such that depression at weeks 0, 8, and 16 predicted the mediators at weeks 8, 16, and 40, respectively and benefit-finding at weeks 16, 40, and 64, respectively. In this circumstance, depression is lagged two time points from the outcome of benefit-finding. While no significant effect was found for depression lagged two time points from benefit-finding, there was a statistically significant effect for depression lagged one time point from benefit-finding. As a result, all subsequent models were analyzed with both predictors and mediators lagged one time point from the outcome.

Random-effect models, after entry of covariates, confirmed that lagged depression significantly predicted benefit-finding at the next time point (estimate = −0.58, SE = 0.13, df = 425, t = −4.58, p < .0001), such that greater improvement in depression following treatment predicted increased benefit-finding over the course of the study.

Depression, Optimism, and Positive Affect

Random-effect models, after entry of covariates, confirmed that depression significantly predicted optimism (estimate = −0.20, SE = 0.03, df = 406, t = −7.26, p < .0001) and positive affect (estimate = −0.50, SE = 0.04, df = 435, t = −11.20, p < .0001), such that greater improvement in depression predicted increased optimism and positive affect.

Optimism, Positive Affect, and Benefit-Finding

Random-effect models, after entry of covariates, confirmed that both lagged optimism (estimate = 0.87, SE = 0.21, df = 395, t = 4.13, p < .0001) and lagged positive affect (estimate = 0.24, SE = 0.12, df = 438, t = 3.41, p < .001) predicted benefit-finding, such that greater optimism and positive affect predicted enhanced benefit-finding later in time.

Relationship Between Depression and Benefit-Finding Across Treatments

Our prior analyses showed no differences between the two types of therapy on depression or positive affect one year after treatment (Mohr et al., 2005). Nevertheless, we examined whether T-CBT (vs. T-SEFT) showed a stronger effect on benefit-finding through greater improvements in depression. We conducted an identical model to the ones described above predicting benefit-finding, but included an interaction term for Therapy × Depression. As we found no significant interaction of our intervention with depression, treatment modality interactions were not pursued in further analyses.

Testing the Indirect Effect of Positive Affect and Optimism

Because the first three of Baron and Kenny's (1986) criteria for testing mediation were met, the final set of multilevel random-effect models examined positive affect and optimism as mediators of the relationship between improvements in depression and increased benefit-finding. As shown in Table 3, lagged optimism and lagged positive affect both met criteria for complete mediation. In the final model, improved depression no longer significantly predicted benefit-finding once optimism was added to the model, thereby meeting Baron and Kenny criteria for mediation. Additionally, results of the bootstrap procedure showed the indirect effects of optimism (coeff = −0.28, SE = 0.07, 95% CI: −0.43, −0.16) and of positive affect (coeff = −0.38, SE = 0.08, 95% CI: −0.54, −0.22) were both statistically significant.

Table 3. Parameter Estimates for Positive Affect and Optimism as Mediators of the Relationship Between Depression and Benefit-Finding.

| Effect | Estimate | SE | t |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | |||

| Intercept | 90.51 | 3.80 | 23.85** |

| Time | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.24 |

| Time since diagnosis | 0.25 | 0.14 | 1.80 |

| Therapy type | 0.92 | 2.76 | 0.34 |

| Depression | −0.58 | 0.13 | −4.58** |

| Model 2 | |||

| Intercept | 61.62 | 6.25 | 9.85** |

| Time | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.15 |

| Time since diagnosis | 0.23 | 0.12 | 1.89 |

| Therapy type | 1.57 | 2.41 | 0.65 |

| Depression | −0.20 | 0.15 | − 1.39 |

| Positive affect | 0.36 | 0.14 | 2.59* |

| Optimism | 0.82 | 0.21 | 3.84** |

Note. All longitudinally collected predictors and mediators were lagged one time interval.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Testing of Alternative Temporal Models

While we had specifically hypothesized a temporal relationship between depression, the mediators of positive affect and optimism, and benefit-finding as the outcome, we examined alternative temporal models as a further test of our hypotheses. Permuting the variables (e.g., making predictors or mediators outcomes, making outcomes mediators or predictors, etc.) resulted in nine potential models, each of which we tested. Two main findings emerged from these exploratory analyses. First, we did not find any support for an alternative temporal model for positive affect. However, the relationships among depression, optimism, and benefit-finding were more temporally interchangeable.

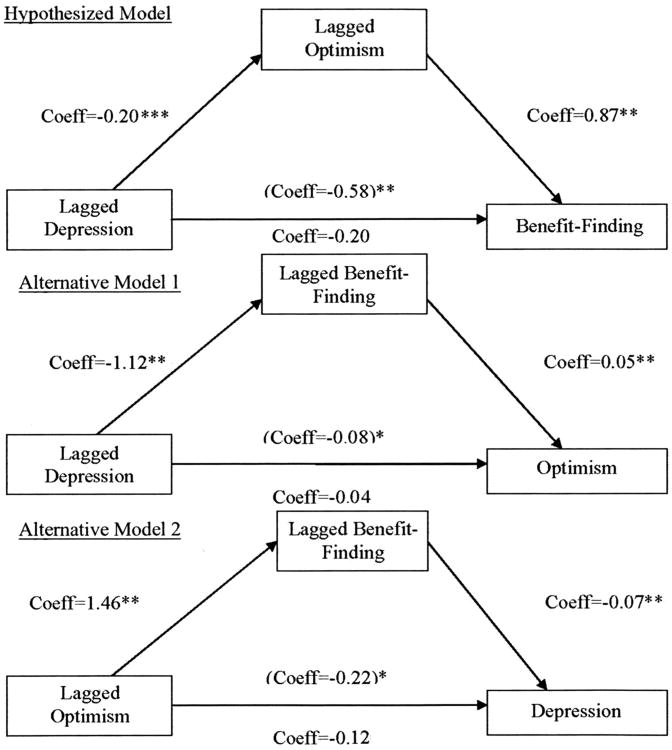

Figure 1 displays the three statistically significant mediational models for depression, optimism, and benefit-finding, each adjusted for time since diagnosis and therapy type. The first is our hypothesized model, which was empirically supported by our multilevel models described earlier. The second and third multilevel random-effects models, both presented in Figure 1, also met full criteria for mediation. The second model shows that benefit-finding completely mediated the relationship between lagged depression and optimism. Results of the bootstrap procedure showed the indirect effects of benefit-finding (coeff = − 0.12, SE = 0.01, 95% CI: −0.17, −0.09) was statistically significant. Finally, the third model shows that benefit-finding also completely mediated the relationship between lagged optimism predicting later depression. In addition, results of the bootstrap procedure showed the indirect effects of benefit-finding (coeff = −0.08, SE = 0.03, 95% CI: −0.15, −0.03) was statistically significant.

Figure 1.

Significant mediational models for the relationships among depression, optimism, and benefit-finding. The coefficient in parentheses is from the model that did not include the mediator. *p < .01; **p < .0001.

Discussion

Our prospective, longitudinal study examined whether reductions in depression were associated with increased levels of benefit-finding among patients diagnosed with MS. In addition, we examined whether positive affect and optimism mediated the relationship between depression and benefit-finding. Three main findings were obtained. First, we found that improving depression led to subsequent increases in benefit-finding over the course of 1 year. Second, the relationship between improved depression and enhanced benefit-finding were completely mediated by increased positive affect and optimism. Third, the relationship of depression, optimism, and benefit-finding is not solely unidirectional; examination of alternative temporal models revealed that benefit-finding also mediated the relationship between depression and optimism over time.

An important finding of this study is that a psychotherapeutic intervention was associated with an increase in benefit-finding for MS patients, and both T-CBT and T-SEFT were equally effective in doing so. This finding contrasts with those of Antoni et al. (2001), who found that their CBSM-group intervention produced greater reductions in depression and increases in benefit-finding. However, it is difficult to directly compare findings from this study to those of Antoni et al., as the latter employed a no-treatment control-group, while both of our therapy arms were active therapy conditions.

Although we were not able to examine directly the specific therapeutic interventions that promoted benefit-finding, both positive affect and optimism appear to bear significant longitudinal relationships to benefit-finding after the completion of therapy. Our data also support the application of the Broaden-and-Build and Expectancy-Value models in understanding the relationship between improved depression and enhanced benefit-finding, as both models provide related, yet, unique explanations for this relationship. For the Broaden-and-Build model, our findings support the idea that improving depression is associated with a subsequent “broadening” response of increased positive affect. The broadening effect is thought to lead to greater life opportunities and, thus, more resilience. In this study, we were able to establish empirically that improvements in positive affect were associated with enhanced benefit-finding in MS.

Our results regarding the significant indirect effect of optimism also provide empirical support to the Expectancy-Value Model (Carver & Scheier, 1998, 2003). According to the Expectancy-Value Model, optimism assists individuals in pursuing their valued life goals, even in the face of hardship. Furthermore, optimistic individuals would be expected to seek opportunities to alter their illness experiences and thrive under adverse conditions. The two theoretical models examined in this study complement one another in that positive affect and optimistic cognitions both may lead to resiliency. Data from the current study confirm that positive expectancies can be increased through treating depression and, importantly, increased optimism is one mechanism by which MS patients appear to enhance their benefit-finding over time.

Interestingly, our exploratory analyses suggest that benefit-finding may also be a mechanism that accounts for the relationship between depression and optimism. While this was not an a priori hypothesis, the findings fit well into the Expectancy-Value Model. Engaging in goals or behaviors to overcome adversity would likely give rise to greater positive expectancies and vice versa, as we have shown, which may then improve depression. Furthermore, improving depression may motivate individuals to engage in benefit-finding, leading them to feel more optimistic over time.

One limitation of our study lies in our benefit-finding measure. According to expectancy value theory (Scheier, Carver, & Bridges, 1994), people holding positive expectancies should be more likely to engage in their goals to overcome difficult life circumstances. While it may be tempting to conclude optimism leads to a greater capacity for making positive changes, our benefit-finding measure does not necessarily reflect the actual attainment of those goals. For example, it is equally as likely increased benefit-finding is simply a sign of wishful thinking or positive illusions. Future research needs to replicate these findings with a benefit-finding measure that identifies actual goal attainment as well as self-perceived changes in one's behaviors and attitudes over time (see Frazier & Kaler, 2006, for a discussion).

Another limitation lies in the timing of our assessments, which may have affected our ability to model relationships over time. Contrary to our expectations, we were not able to show a significant effect for depression lagged two time points from benefit-finding, which affected our ability to test mediation in the traditional sense, where the predictors precede the mediators, which then precede the outcomes. This may have been due to the length of the lags; two time points resulted in lags of 4 to 6 months. Consequently, we may have missed the more immediate effects on benefit-finding over time, as the mechanisms by which these variables influence one another may operate on a much shorter time interval. Weekly or even daily assessments of these variables in the context of depression treatment would be useful in the future.

There are also limitations to the generalizability of our study sample. Our sample had been diagnosed with MS for an average of seven years. Because MS affect Caucasians primarily, the sample was fairly racially homogenous. Furthermore, we recruited patients who had moderate to severe levels of depression and moderate levels of disability. Our sample of MS patients differs from the larger population of people diagnosed with MS in that they were more depressed and more physically disabled than the average MS patient. These findings may not apply to patients who have been recently diagnosed with MS. Furthermore, our methods of specifically recruiting patients with clinical levels of depression differ from the recruitment strategies of most studies of chronically ill patients, such as cancer, and therefore may not generalize well to other populations. Despite these limitations, our methods allowed us to access a more chronically disabled, distressed population than has been previously represented in the literature.

These data suggest that both positive cognitions and positive affect appear to promote resilience in MS. Taken together, our findings may have significant clinical implications, both for MS patients specifically, as well as for depressed populations more generally. Our research suggests that psychotherapy for patients with clinical levels of depression has both a direct and indirect effect on benefit-finding. Importantly, positive affect and optimism are direct mechanisms by which benefit-finding improves. While not examined in this study, benefit-finding appears to confer positive health outcomes for chronically ill individuals, such as improved immune functioning (Bower, Kemeny, Taylor, & Fahey, 1998; Cruess et al., 2000; McGregor et al., 2004; Milam, 2006), reduced number of medical visits (Stanton et al., 2002), and better physical functioning (Danoff-Burg & Revenson, 2005). Future research should continue to examine benefit-finding, both as a parameter of positive psychological adjustment to illness and as a predictor of physical health in chronically ill individuals.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health R01 MH59708 and K08 MH068257.

References

- Antoni MH, Lehman JM, Kilbourn KM, Boyers AE, Culver JL, Alferi SM, et al. Cognitive-behavioral stress management intervention decreases the prevalence of depression and enhances benefit finding among women under treatment for early-stage breast cancer. Health Psychology. 2001;20:20–32. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.20.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armeli S, Gunthert KC, Cohen LH. Stressor appraisals, coping, and post-event outcomes: The dimensionality and antecedents of stress-related growth. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2001;20:366–395. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck JS. Cognitive therapy: Basics and beyond. xiv. New York: Guilford Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bower JE, Kemeny ME, Taylor SE, Fahey JL. Cognitive processing, discovery of meaning, CD4 decline, and AIDS-related mortality among bereaved HIV-seropositive men. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:979–986. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.6.979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Scheier MF. On the self-regulation of behavior. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Carver C, Scheier MF. Optimism. In: Lopez SJ, Snyder CR, editors. Positive psychological assessment: A handbook of models and measures. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2003. pp. 75–89. [Google Scholar]

- Chwastiak L, Ehde DM, Gibbons LE, Sullivan M, Bowen JD, Kraft GH. Depressive symptoms and severity of illness in multiple sclerosis: Epidemiologic study of a large community sample. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:1862–1868. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.11.1862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruess DG, Antoni MH, McGregor BA, Kilbourn KM, Boyers AE, Alferi SM, et al. Cognitive-behavioral stress management reduces serum cortisol by enhancing benefit finding among women being treated for early stage breast cancer. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2000;62:304–308. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200005000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danoff-Burg S, Revenson TA. Benefit-finding among patients with rheumatoid arthritis: Positive effects on interpersonal relationships. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2005;28:91–103. doi: 10.1007/s10865-005-2720-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis CG, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Larson J. Making sense of loss and benefiting from the experience: Two construals of meaning. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;75:561–574. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.75.2.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazier PA, Kaler ME. Assessing the validity of self-reported stress-related growth. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:859–869. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.5.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist. 2001;56:218–226. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.56.3.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg LS. Integrating an emotion-focused approach to treatment into psychotherapy integration. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration. 2002;12:154–189. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart S, Fonareva I, Merluzzi N, Mohr DC. Treatment for depression and its relationship to improvement in quality of life and psychological well-being in multiple sclerosis patients. Quality of Life Research. 2005;14:695–703. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-1364-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helgeson VS, Reynolds KA, Tomich PL. A meta-analytic review of benefit-finding and growth. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:797–816. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.5.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssens A, van Doorn PA, de Boer JB, van der Meche FG, Passchier J, Hintzen RQ. Perception of prognostic risk in patients with multiple sclerosis: The relationship with anxiety, depression, and disease-related distress. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2004;57:180–186. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(03)00260-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz RC, Flasher L, Cacciapaglia H, Nelson S. The psychosocial impact of cancer and lupus: A cross validation study that extends the generality of “benefit-finding” in patients with chronic disease. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2001;24:561–571. doi: 10.1023/a:1012939310459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer HC, Stice E, Kazdin A, Offord D, Kupfer D. How do risk factors work together? Mediators, moderators and independent, overlapping, and proxy risk factors. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:848–856. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.6.848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2004;30:41–62. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallinckrodt B, Abraham WT, Wei M, Russell DW. Advances in testing the statistical significance of mediation effects. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2006;53:372–378. [Google Scholar]

- McGregor BA, Antoni MH, Boyers A, Alferi SM, Blomberg BB, Carver CS. Cognitive-behavioral stress management increases benefit finding and immune function among women with early stage breast cancer. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2004;56:1–8. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00036-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuigan C, Hutchinson M. Unrecognised symptoms of depression in a community-based population with multiple sclerosis. Journal of Neurology. 2006;252:219–223. doi: 10.1007/s00415-005-0963-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milam JE. Posttraumatic growth among HIV/AIDS patients. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2004;34:2353–2376. [Google Scholar]

- Milam JE. Posttraumatic growth and HIV disease progression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:817–827. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.5.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr DC, Boudewyn AC, Goodkin DE, Bostrom A, Epstein L. Comparative outcomes for individual cognitive-behavior therapy, supportive-expressive group psychotherapy, and sertraline for the treatment of depression in multiple sclerosis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:942–949. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr DC, Dick LP, Russo D, Pinn J, Boudewyn AC, Likosky W, et al. The psychosocial impact of multiple sclerosis: Exploring the patient's perspective. Health Psychology. 1999;18:376–382. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.18.4.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr DC, Hart SL, Julian L, Catledge C, Honos-Webb L, Vella L, et al. Telephone-administered psychotherapy for depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:1007–1014. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.9.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr DC, Likosky W, Bertagnolli A, Goodkin DE, Van Der Wende J, Dwyer P, et al. Telephone-administered cognitive-behavioral therapy for the treatment of depressive symptoms in multiple sclerosis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:356–361. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.2.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr DC, Vella L, Hart SL, Heckman T, Simon GE. The effect of telephone-administered psychotherapy on symptoms of depression and attrition: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2008.00134.x. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pakenham K. Benefit finding in multiple sclerosis and associations with positive and negative outcomes. Health Psychology. 2005a;24:123–132. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.2.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pakenham K. Relations between coping and positive and negative outcomes in careers of persons with multiple sclerosis (MS) Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings. 2005b;12(1):25–38. [Google Scholar]

- Patten SB, Beck CA, Williams JV, Barbui C, Metz LM. Major depression in multiple sclerosis: A population-based perspective. Neurology. 2003;61:1524–1527. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000095964.34294.b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson C. The future of optimism. American Psychologist. 2000;55:44–55. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potts MK, Daniels M, Burnam MA, Wells KB. A structured interview version of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale: Evidence of reliability and versatility of administration. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1990;24:335–350. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(90)90005-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers. 2004;36:717–731. doi: 10.3758/bf03206553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadovnick AD, Eisen K, Ebers GC, Paty DW. Cause of death in patients attending multiple sclerosis clinics. Neurology. 1991;41:1193–1196. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.8.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute Inc. SAS Version 8.02. Cary, NC: Author; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Scheier MF, Carver CS, Bridges MW. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): A reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67:1063–1078. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.67.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheier MF, Carver CS. Effects of optimism on psychological and physical well-being: Theoretical overview and empirical update. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1992;16:201–228. [Google Scholar]

- Sears SR, Stanton AL, Danoff-Burg S. The yellow brick road and the emerald city: Benefit-finding, positive reappraisal coping, and posttraumatic growth in women with early stage breast cancer. Health Psychology. 2003;22:487–497. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.22.5.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seligman ME, Castellon C, Cacciola J, Schulman P, Luborsky L, Ollove M, et al. Explanatory style change during cognitive therapy for unipolar depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1988;97:13–18. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.97.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharrack B, Hughes RAC. The Guy's Neurological Disability Scale (GNDS): A new disability measure for multiple sclerosis. Multiple Sclerosis. 1999;5:223–233. doi: 10.1177/135245859900500406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel K, Schrimshaw EW. Perceiving benefits in adversity: Stress-related growth in women living with HIV/AIDS. Social Science & Medicine. 2000;51:1543–1554. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00144-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME. Asymptotic intervals for indirect effects in structural equations models. In: Leinhardt S, editor. Sociological methodology. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1982. pp. 290–312. [Google Scholar]

- Solari A, Ferrari G, Radice D. A longitudinal survey of self-assessed health trends in a community cohort of people with multiple sclerosis and their significant others. Journal of Neurological Sciences. 2006;243:13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton AL, Danoff-Burg S, Sworowski LA, Collins CA, Branstetter A, Rodriguez-Hanley A, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of written emotional expression and benefit finding in breast cancer patients. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2002;20:4160–4168. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.08.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urcuyo KR, Boyers AE, Carver CS, Antoni MH. Finding benefit in breast cancer: Relations with personality, coping, and concurrent well-being. Psychology & Health. 2005;20:175–192. [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54:1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]