Abstract

Genotype imputation has become a standard option for researchers to expand their genotype datasets to improve signal precision and power in tests of genetic association with disease. In imputations for family-based studies however, subjects are often treated as unrelated individuals: currently, only BEAGLE allows for simultaneous imputation for trios of parents and offspring; however, only the most likely genotype calls are returned, not estimated genotype probabilities. For population-based SNP association studies, it has been shown that incorporating genotype uncertainty can be more powerful than using hard genotype calls. We here investigate this issue in the context of case-parent family data. We present the statistical framework for the genotypic transmission-disequilibrium test (gTDT) using observed genotype calls and imputed genotype probabilities, derive an extension to assess gene-environment interactions for binary environmental variables, and illustrate the performance of our method on a set of trios from the International Cleft Consortium. In contrast to population-based studies, however, utilizing the genotype probabilities in this framework (derived by treating the family members as unrelated) can result in biases of the test statistics toward protectiveness for the minor allele, particularly for markers with lower minor allele frequencies and lower imputation quality. We further compare the results between ignoring relatedness in the imputation and taking family structure into account, based on hard genotype calls. We find that by far the least biased results are obtained when family structure is taken into account and currently recommend this approach in spite of its intense computational requirements.

Keywords: imputation, transmission disequilibrium test, case-parent trios, probabilistic genotypes

INTRODUCTION

The availability of large and dense public reference genotype datasets has given researchers the opportunity to substantially expand their own genotype datasets through insilico imputation methods [Li et al., 2009]. Using reference panels from datasets such as the International HapMap Project [International HapMap Consortium et al., 2007] and the 1000 Genomes Project [1000 Genomes Project Consortium et al., 2010], sufficient population-specific information on haplotype frequency is becoming available to allowimputation to increase the number of markers with genotype information in a study dataset genotyped on microarrays by a factor of two or more. In spite of potential uncertainty in these imputed genotype calls, the resulting imputed genotypes can lead to increased power and precision in locating a region of genetic association with an outcome of interest [Chen and Abecasis, 2007; Louis et al., 2010; Zheng et al., 2011].

Although methods for performing imputation have been developed, methods of downstream analysis that can work with continuous probability values produced as imputation output are still in development. Substantial work has been done for case-control studies, including methods originally aimed at addressing differential data sources [Plagnol et al., 2007] and “fuzzy” genotype calls [Louis et al., 2010; Marchini et al., 2007]. However, no method has yet been developed for case-parent trio data. Although imputed data can be discretized by selecting the most-likely genotype at each marker, this may introduce bias or reduce power when uncertainty in the imputed probabilities is large [Louis et al., 2010; Zheng et al., 2011].

In this paper, we first present a method for extending the genotypic transmission disequilibrium test (gTDT) [Schaid, 1996], designed to test for linkage and association in trios consisting of a mother, father, and affected offspring, to imputed genotype probabilities. To our knowledge, the method presented here is the first to extend the gTDT to a setting with non-discrete genotypes. We also present a formulation for assessing gene-environment interactions in this context for binary environmental variables. We demonstrate our method on a dataset of genotypes from families included in the International Cleft Consortium [Beaty et al., 2010]. The implementation of our method is based on a strategy presented by Schwender et al. [2011], obtaining closed-form solutions for the parameter estimates in gTDTs, and thus allowing assessment of hundreds of thousands of markers within minutes.

Whereas the specific benefits of employing non-discrete genotypes have been demonstrated for case-control data [Chen and Abecasis, 2007; Louis et al., 2010; Zheng et al., 2011], we examined whether the same holds for case-parent trio analyses. Currently, only BEAGLE [Browning and Browning, 2009] imputes genotypes for both individuals and families using reference haplotypes, but returns genotypic probabilities only when individuals are treated as unrelated (i.e., BEAGLE returns forced genotype calls when the family structure is taken into account). However, when using these probabilistic genotypes, we discovered biases in the test statistics toward a protective effect of the minor allele, particularly for markers with low minor allele frequencies and lower imputation quality scores. We explored whether these biases stem from employing genotype uncertainties per se by comparing results based on hard genotype calls obtained through imputation either ignoring family structure or taking family structure into account. We found that substantial bias remains in results from hard calls generated ignoring relatedness, and therefore strongly recommend taking family structure into account during the imputation process, to alleviate this bias. Nonetheless, the biggest gain of efficiency and validity will likely be observed when imputation strategies can use family structure to generate probabilistic genotypes.

MATERIALS

Our new method is designed for datasets on which imputation has been performed so each biallelic marker for each individual consists of probabilities for each of the three possible genotypes. Whereas existing methods of gTDT analysis could be applied to imputed datasets where the most likely genotype is chosen for each individual, it has been shown that incorporating genotype uncertainty improves power over applying methods with incorrect calls [Louis et al., 2010; Zheng et al., 2011]. Our method applies to datasets consisting of any number of complete trios, including a mother, father, and affected offspring.

We first test our method on a set of 1,551 case-parent trios drawn from the International Cleft Consortium [Beaty et al., 2010]. The trios considered here have a single affected offspring diagnosed with cleft lip, with or without cleft palate (CL/P). Samples were genotyped at the Center for Inherited Disease Research (CIDR) using the Illumina Human610-Quadv 1_B Beadchip. Imputation was performed by the GENEVA Coordinating Center using BEAGLE [Browning and Browning, 2009], treating all individuals as unrelated. Only subjects of Asian or European ancestry were candidates for imputation, and a HapMap Phase III reference panel was used. SNPs from the Illumina microarray were first filtered based on quality and minor allele frequency (MAF), and then further filtered based on a strand check, concordance with previous HapMap calls for those samples also included in HapMap, and presence of the marker in the HapMap Phase III consensus set. The final size of the imputation basis was 491,502 markers, which was then imputed up to a set of 1,387,466 markers, for an increase of 895,964 markers. Quality metrics are provided for each imputed site to allow for downstream filtering based on imputation uncertainty.

To further examine the statistical properties of our method, we performed additional imputations, restricting our marker set to those on chromosome 1. We carried out imputations via BEAGLE, using the denser HapMap II reference panel. We imputed the 895 Asian and 656 European trios separately, using the HapMap II JPT+CHB (Japanese in Tokyo, Japan and Han Chinese in Beijing, China) and CEU (Utah residents with ancestry from northern and western Europe) reference panels, respectively. Since the type I errors of the TDT-based association analyses are not affected by genetic heterogeneity, we merged datasets for downstream analysis, for a total of 156,858 markers (35,358 genotyped and 121,500 imputed). Imputations were carried out in two ways: by treating all subjects as unrelated (producing both genotype call probabilities and the most likely genotype calls) and by taking the trio design into account (producing only genotype calls, but no genotype probabilities). In the remainder of the paper, we refer to these imputed data as PU, CU and CR, respectively (with subscript U indicating that the subjects were treated as unrelated in the imputation, subscript R that they were treated as related, and letters P and C indicating probabilities and calls, respectively).

METHODS

TESTING FOR MAIN EFFECTS USING GENOTYPE PROBABILITIES

In this paper, we follow the notation introduced in Louis et al. [2010] and Schwender et al. [2011]. We consider data on a set of n trios at a single locus, and assume we have genotype probabilities at this locus for each member, , , , i = 1, …, n, j ∈ {0, 1, 2}, with m, f, and 0 indicating genotype probabilities for the mother, father, and proband, respectively, i.e., . Let , and let be the set of these genotype probabilities for family i.

We use conditional logistic regression to perform the gTDT, with each stratum consisting of one trio, with its affected offspring and three unaffected pseudo-controls whose genotypes are generated as the untransmitted pairs of parental alleles. Given genotypes , for the affected proband and the three pseudo-controls, where k = 0 for the proband, and k = 1, 2, 3 for the pseudo-controls, the predictor of case-control status in this model is dependent on the genetic effect assumed. For example, for an additive model. Let be the vector of these predictors for family i. The response variable in the regression model is the case-control status of the proband and the unaffected pseudo-controls, i.e., and k ≠ 0 [Breslow et al., 1978]. Let yi = (1, 0, 0, 0) be the vector of these response variables for family i.

Given this setup, we can write the contribution to the joint distribution of the data from family i as

where χ is the set of possible values of xi given the assumed genetic model and Mendelian constraints of the observed parental mating type (for example, see Table I for the 10 possible trio configurations under an additive model).

TABLE I.

For the 10 possible family types under Mendelian inheritance in an additive genetic model, we give the contribution to the likelihood and define the symbols αl, which give the sums across families of (renormalized) probabilities for each family falling into a particular family type. The genotypes are coded by the number of minor alleles. The contributions of mating types below the dashed line have no effect on the parameter estimation. Adapted from Schwender et al. [2011]

| Parents | Affected child |

Pseudo- controls |

Weight cl (βadd) in likelihood |

Sum αl of family probabilities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0, 1 | 0 | 0, 1, 1 | α 1 | |

| 0, 1 | 1 | 0, 0, 1 | α 2 | |

| 1, 2 | 1 | 1, 2, 2 | α 3 | |

| 1, 2 | 2 | 1, 1, 2 | α 4 | |

| 1, 1 | 0 | 1, 1, 2 | α 5 | |

| 1, 1 | 1 | 0, 1, 2 | α 6 | |

| 1, 1 | 2 | 0, 1, 1 | α 7 | |

|

| ||||

| 0, 0 | 0 | 0, 0, 0 | α 8 | |

| 0, 2 | 1 | 1, 1, 1 | α 9 | |

| 2, 2 | 2 | 2, 2, 2 | α 10 | |

This yields a log-likelihood

| (1) |

To estimate β, we want to maximize this expression with respect to β, obtaining

Under a conditional logistic regression model, note that we have

| (2) |

which we can define as cl(β). This allows us to regroup terms in the above to obtain

| (3) |

where

The last equality follows from the independence of xi and yi under the null hypothesis.

The above simplification of the derivative of the log-likelihood into a sum over a small number of genotype configurations allows derivation of closed-form estimates for all model parameters, as a function of the sums of probabilities, pl. A similar derivation in Schwender et al. [2011] led to a substantial increase in computational efficiency by avoiding iterative estimation of the conditional logistic regression parameters.

Given a particular genetic model (additive, dominant, or recessive) and under Mendelian inheritance, we can determine the set of possible predictor variables, χ, and for any set of predictor variables xl we can compute . Tables I-III are adapted from Schwender et al. [2011] and give the respective contributions to the likelihood of each possible trio configuration and define symbols for sums of these probabilities in each case for additive, dominant, and recessive genetic models.

TABLE III.

For the six possible combinations of affected case and pseudo-controls (in that order) under Mendelian inheritance in a recessive model, we give the contribution to the likelihood and define the symbols ρl. The symbols αl refer to those defined in Table I. Adapted from Schwender et al. [2011]

| Combination χl |

Weight in likelihood |

Sum ρl of family probabilities |

|---|---|---|

| 0, 0, 1, 1 | ρ1 (= α3) | |

| 1, 0, 0, 1 | ρ2 (= α4) | |

| 0, 1, 1, 1 | ρ3 (= α5 + α6) | |

| 1, 1, 0, 1 | ρ4 (= α7) | |

| 0, 0, 0, 0 | ρ5 (= α10) | |

| 1, 1, 1, 1 | ρ6 (other αl) |

Referring to Table I, for an additive genetic model there are 10 different probability sums, denoted α1 through α10 with, for example,

These probabilities can be calculated assuming genotypes are measured independently between all subjects, and hence the probability of a particular combination of genotypes in the parents and the affected offspring is simply the product of the probabilities of each genotype in all individuals. Of course, certain combinations are not possible under Mendelian inheritance, so these product probabilities are renormalized to sum to 1 across all permissible scenarios. From the example above,

In the additive model setting, equation 3 can be written as a function of αi as

Setting , we can solve for βadd, and obtain the parameter estimates:

For the dominant and recessive models, we obtain

with

and

with

respectively. The definitions of αl, δl, and ρl appear in Tables I-III.

Standard errors of these parameter estimates can be obtained by plugging them into the negative inverse of the second derivative of the log-likelihood. For example, in the case of the additive model, defining , we have

Similar estimates can be derived for and . Along with these estimates of their variances, the parameter estimates can be used to compute the gTDT statistic to assess the significance of association between each marker and the trait of interest. Again, using the additive model as an example, we compute , which is asymptotically -distributed under the null model of no linkage and no association.

ASSESSING SIGNIFICANCE OF GENE-ENVIRONMENT INTERACTIONS

In addition to the primary effect of a particular genotype on disease status, the interaction between genotype and an environmental factor may be significant and detecting such an interaction may shed useful light on disease mechanisms. Similar to Schwender et al. [2011], we can extend our test to include assessment of gene-environment interactions for binary environmental variables, a class which encompasses many important traits such as maternal smoking status or alcohol consumption, but also “surrogates” for environment such as gender.

Because in the gTDT the unit of observation is a single trio, there is complete confounding between environmental exposure and the strata in the conditional likelihood so that the main effect of the environmental factor cannot be estimated. However, the gene-environment interaction effect is easily estimable for binary environmental factors. As derived in Schwender et al. [2011] for deterministic genotype calls and in the Appendix for fuzzy genotype calls, the gene-environment interaction parameter, βGE, can be estimated by taking the difference between the main-effect estimates calculated separately for families of probands exposed and unexposed to the binary environmental factor. That is, under any genetic model, we calculate for the unexposed families, and for the exposed families, and we can then use

as an estimate of the gene-environment effect. The gTDT statistic to assess significance of this effect can be formed by taking

RESULTS

ANALYSIS OF THE INTERNATIONAL CLEFT CONSORTIUM WHOLE-GENOME DATA

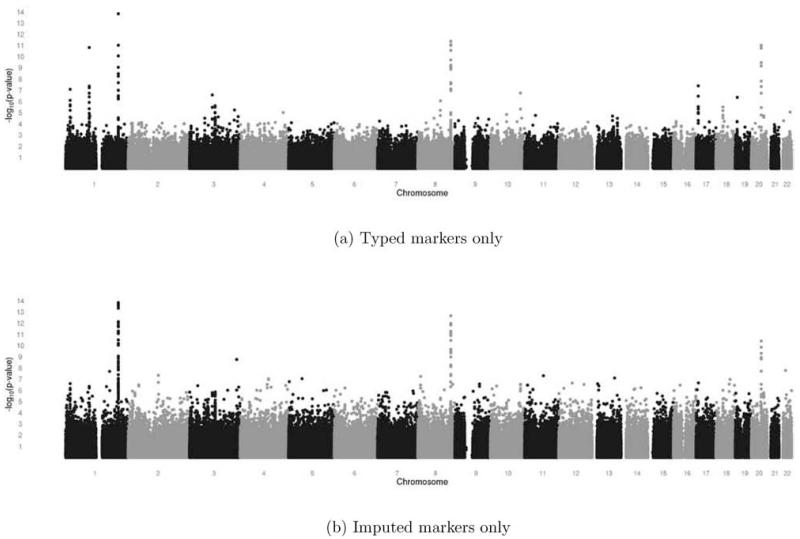

We first used our method to analyze the set of imputed SNPs for 1,551 case-parent trios provided by the International Cleft Consortium (see Materials). To examine effects of imputation on the overall signal from these data, Figure 1 shows a comparison of Manhattan plots with and without imputed markers. The upper plot uses only those markers contained in the imputation base (i.e., genotyped markers passing pre-imputation filters), while the lower plot contains all new post-imputation markers which passed a quality control filter, requiring estimated imputation r2 values (meant to measure the correlation between estimated and true genotypes) greater than 0.8. We found that this strict filter was helpful in removing spurious low P-values and sharpening the true association signal.

Fig. 1.

Manhattan plots showing results from the additive gTDT for 1,551 families from the whole-genome imputed dataset. (a) genotyped markers included in the imputation base alone (491,502 markers); (b) all imputed markers with an imputation r2 greater than 0.8 (664,469 markers out of a complete imputation set of 895,964, or 74%).

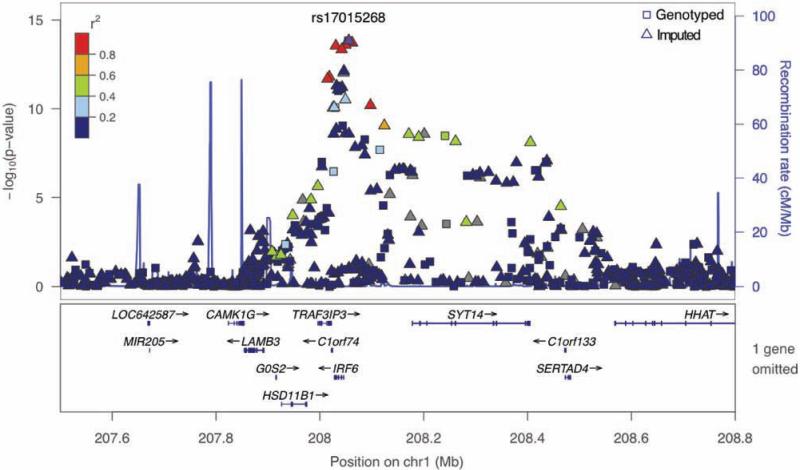

In Figure 2, we show results of our initial gTDT analysis at a locus on chromosome 1, with plotting symbols indicating whether a position was part of the imputation basis (i.e., a genotyped marker) or an imputed locus. The strongest signals came from imputed markers, again providing evidence for the potential benefit of leveraging these data.

Fig. 2.

Enlargement of a signal region on chromosome 1 including IRF6, showing contributions from genotyped and imputed markers from the whole-genome data set to the gTDT signal. Colors indicate linkage disequilibrium (also labeled r2, though different from the imputation r2) relative to the marker with the strongest signal. Plotted using locusZoom [Pruim et al., 2010].

For computation time benchmarking, we used a compute node with an AMD Opteron CPU with 2.7-GHz processor speed and 64-GB RAM and repeated each computation 10 times. Timing did not vary substantially between replicate runs, and computing time per chromosome was roughly linear in the number of markers. The parameter estimates, standard errors, confidence intervals, and P-values for the entire dataset were calculated in about half an hour. To assess the required computing times for the gene-environment interaction test, we considered proband gender to illustrate performance for a binary environmental factor, and tested for gene-environment interactions under an additive model. Timing was very similar to the main-effect-only test, with the sum across chromosomes of the median compute times for each chromosome at around 40 min (compared to 34 min for the main-effect tests).

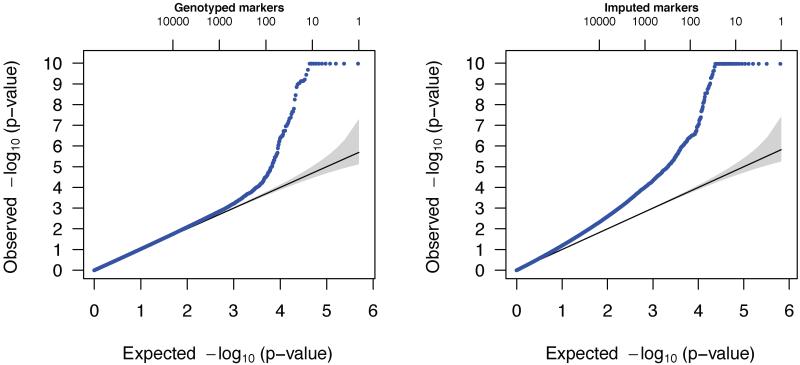

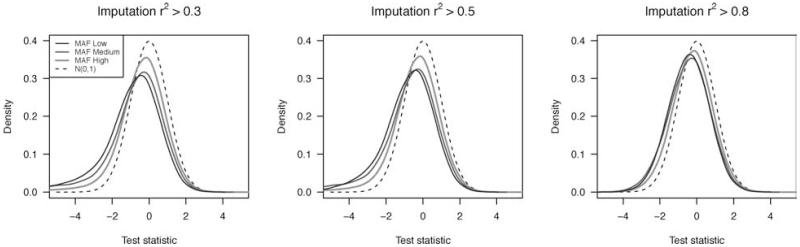

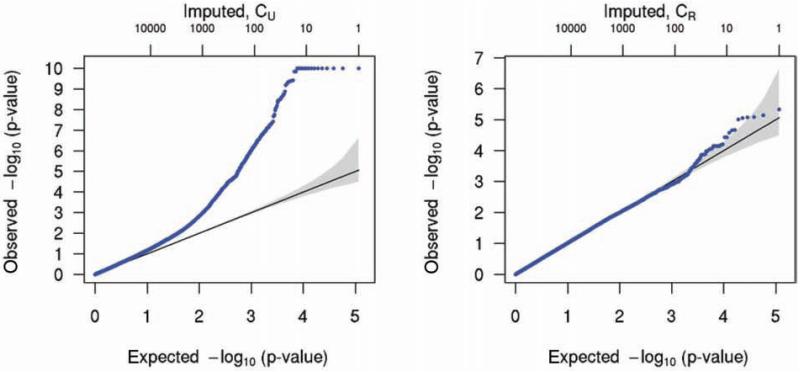

However, even after employing a stringent cutoff of 0.8 on the imputation r2 values [defined on page 220 in Browning and Browning, 2009], we observed an inflation of the test statistics relative to an assumed standard normal distribution. In Figure 3, the distributions of P-values for genotyped markers and imputed markers (with an imputation r2 cutoff of 0.8) are compared. It appears that the statistics from the genotyped markers display a slight type I error inflation, likely due to genotyping errors, though most of the deviation from the null is due to the actual association signal in the data [Beaty et al., 2010]. However, the statistics from the imputed marker probabilities are more extreme. Figure 4 displays the estimated densities of the gTDT statistics for the imputed markers only, shown for different cutoffs for imputation of r2, and for different MAF bins. Note that we computed MAF directly from the genotype probabilities. We found that both MAF and imputation r2 have an impact on the bias in the distribution of the test statistics. Interestingly, the bias is predominantly in the direction of assigning protective status to the minor allele. Using a strict imputation r2 cutoff of 0.8 ensures that much of the bias is removed, but particularly for low MAFs, some bias remains.

Fig. 3.

Quantile-quantile plots of P-values derived from the genotype calls on all observed markers from the gTDT (left), and derived from genotype probabilities for imputed markers with an imputation r2 greater than 0.8, using our newly derived method (right). The gray shaded regions indicate 95% confidence bands for the order statistics under the global null of no associations. The numbers on the top axis indicate the respective locations for the ordered expected −log10 P-values (e.g., the number 10 indicates the expected value for the tenth smallest P-value on the −log10 scale, for the given number of observed P-values). The plots were truncated at −log10(P) ≈ 10.

Fig. 4.

Density plots of test statistics from the whole-genome imputation dataset for subsets of markers with varying cutoffs of imputation r2, among imputed markers only.Within an r2 cutoff group, markers are grouped byminor allele frequency (less than 5% [low], between 5% and 10% [medium], and above 10% [high]). A standard normal density is included as a reference.

ANALYSIS OF ADDITIONAL IMPUTATION DATA

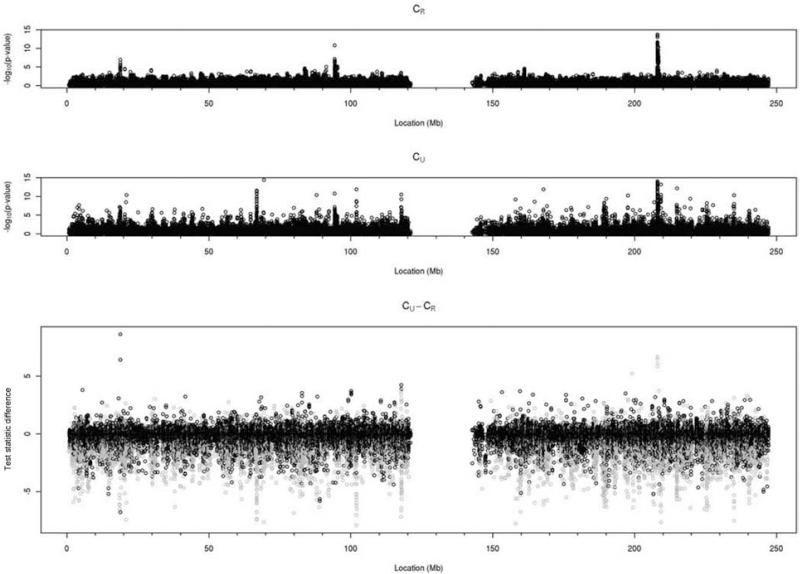

We performed additional imputation on chromosome 1 using the denser HapMap II reference panels for Asians and Europeans, as described above, to further investigate the source of the observed biases. We compared results derived from three different types of imputation data: the results based on genotype probabilities with samples treated as unrelated (PU data), those based on the most likely calls with samples treated as unrelated (CU), and those based on most likely calls with the family structure taken into account (CR). The results from the PU data, as expected, are the same as those obtained on the whole-genome dataset, in that stringent filtering is required to remove spurious signals, and an inflation of type I errors remains even after filtering (data not shown). To delineate the effect of ignoring family information on the observed test statistic biases, we compared distributions of P-values obtained from the CU and CR datasets (Figure 5). Because chromosome 1 contains some strong association signal in the genotyped markers, we removed a set of 493 SNPs located near the association peaks, leaving a set of 114,740 imputed markers which were determined to be polymorphic in both imputed datasets. P-values are shown for all those polymorphic markers, because no imputation r2 is reported when using family information and forcing genotype calls. Although not nearly as inflated as the test statistics from the PU data if no filters were applied, the test statistics from the CU data show much more bias than those from the CR data.

Fig. 5.

Quantile-quantile plots of P-values for results using CU data (left) and CR data (right). Each plot was generated from the same set of 114,730 markers, with markers in association peaks in the genotyped data excluded.

One important difference between using and ignoring family relationships to generate genotype calls is that the former approach prevents Mendelian errors. Although families whose genotypes at a particular marker are inconsistent with Mendelian inheritance are automatically dropped in parameter estimation and hypothesis testing, the number of trios showing Mendelian inconsistencies when family information is ignored indicates a potentially severe bias for the test statistic at that SNP. More importantly, because imputation based on haplotypes from a reference panel, it appears that Mendelian errors can occur in clusters, yielding inflated P-values that look like a real signal (Figure 6). Comparing the chromosome 1 Manhattan plots (all markers shown without filtering on imputation r2) for the CR and CU data indicates an excess of lower P-values when family information is ignored and, in particular, several more regions where the presence of multiple significant P-values seems to indicate true association. However, when correlating these findings with Mendelian errors, a clear pattern emerges, showing that these apparent regions of signal correspond to clusters of markers with large numbers of Mendelian errors (Figure 6, lower panel).

Fig. 6.

Manhattan plots showing the P-values from the analysis of the same markers in the CR (upper panel) and CU data (middle panel). The excess of low P-values and type I errors from the CU data is also reflected in the differences in the test statistics (bottom panel), with SNPs in the top 10% of markers with Mendelian inconsistencies (more than 12 families in the CU data) colored in gray. Regions with many low P-values in the CU but not CR data (for example at about 68MB, 102MB, 118MB) correspond to markers with many Mendelian errors.

DISCUSSION

We have developed a method that accommodates imputed genotype probabilities for the gTDT which produces results in a computationally efficient implementation. Compared to the allelic transmission disequilibrium test (aTDT), the gTDT can be more powerful [Schaid, 1999], allows for testing gene-environment interactions, and also allows for the specification of different genetic models, whereas multiplicative effects are intrinsically assumed in the aTDT [Fallin et al., 2002]. Furthermore, the gTDT, in addition to P-values, also yields parameter estimates, standard errors, and confidence intervals, which cannot be obtained from aTDTs and score tests. We believe that with the advancement of the 1000 Genomes Project and ongoing sequencing efforts, use of imputation to expand on existing genotyping datasets will become even more popular, as the number of markers and haplotypes discovered is constantly growing. Thus, computationally and statistically efficient methods for analysis of imputed genotype data are timely and important.

Previous work has demonstrated that inference for SNP associations in case-control studies can be improved by accounting for genotype uncertainties [Louis et al., 2010; Zheng et al., 2011], however, the picture is less clear in the case-parent trio setting. In this paper, we have derived a method to allow incorporating genotype uncertainties into the gTDT and have shown the results from an initial analysis of a set of trios from the International Cleft Consortium. Applying our method to the set of genotype probabilities currently obtainable from imputation software (which do not take family relationships into account), we observed a skewed distribution for the test statistics, even with strict filtering based on imputation quality. This was observed particularly for markers with low MAFs. Moreover, we also investigated results based on BEAGLE genotype calls, ignoring relatedness versus taking the family structure into account. We found a strong bias in the test statistics when relatedness was ignored in the imputation, and generally, the observed bias was toward a spurious protective minor allele. This is likely due to the fact that genotyping errors in the parents affect the test statistic differently from genotyping errors in the offspring. For example, in a trio with all members having the same homozygous genotype (say AA), an incorrect heterozygous call for the offspring (AB) induces a Mendelian error. Thus, this trio does not contribute to the test statistic, as Mendelian errors are dropped in the gTDT. However, an incorrect heterozygous call for one of the parents does not induce a Mendelian error. For this trio, it appears that the major allele (A), not the minor allele (B), was transmitted from the heterozygous parent (AB) to the homozygous, affected offspring (AA). Thus, the major allele appears to be the risk allele. The same argument applies to the newly introduced gTDT based on the probabilistic genotypes, as all possible genotype combinations in a trio that do not give rise to Mendelian errors are considered, and contribute to the test statistic.

We also found when hard genotype calls are derived without taking family structure into account, the number of Mendelian errors per marker can be used as a surrogate for imputation quality and potential bias in the test statistic for the respective SNP. Particularly worrisome in our studies, however, was the fact that some regions show clustered patterns of Mendelian errors, potentially producing a spurious peak in the Manhattan plots resembling a true signal. Thus, unless it is computationally prohibitive, we believe imputations should be carried out taking family relationship into account whenever possible. Otherwise, very stringent filters need to be employed, and extreme caution should be used when interpreting the findings. Nonetheless, we believe utilizing genotype probabilities may help to refine association loci (see for example the locusZoom plots in the Supplementary Material, where the strongest signal comes from the PU dataset). Since imputation methods are being actively developed, we anticipate that family-based imputations that deliver probabilistic genotypes will be available in the near future. The methods presented in this manuscript will allow for further exploration of the benefits of using “fuzzy” genotype data in case-parent trio analyses.

Supplementary Material

TABLE II.

For the six possible combinations of affected child and pseudo-controls (in that order) under Mendelian inheritance in a dominant model, we give the contribution to the likelihood and define the symbols δl. The symbols αl refer to those defined in Table I. Adapted from Schwender et al. [2011]

| Combination χl |

Weight in likelihood |

Sum δl of family probabilities |

|---|---|---|

| 0, 0, 1, 1 | δ1 (= α1) | |

| 1, 0, 0, 1 | δ2 (= α2) | |

| 0, 1, 1, 1 | δ3 (= α5) | |

| 1, 1, 0, 1 | δ4 (= α6 + α7) | |

| 0, 0, 0, 0 | δ5 (= α8) | |

| 1, 1, 1, 1 | δ6 (other αl) |

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the families who participated in the International Cleft Consortium, and we gratefully acknowledge the invaluable assistance of clinical, field, and laboratory staff who contributed to this study. We particularly acknowledge Mary L. Marazita, Jeffrey C. Murray, and Alan F. Scott, who played critical roles in bringing together the International Cleft Consortium and in carrying out this genome-wide association study. We thank the GENEVA coordinating center for carrying out the imputation analysis on the genome-wide marker panel set, and Shengchao Li for the BEAGLE chromosome 1 imputations.

Support was provided by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Research Training Group 1032 “Statistical Modelling” to H.S.), the National Institute of Health (R01 DK061662 to T.A.L., R01 HL090577 and R01 GM083084 to I.R. and M.A.T., R01 DE014581 to T.H.B., R03 DE021437 to I.R. and T.H.B.), and a CTSA grant to the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions. Funding to support data collection, genotyping, and analysis for the case-parent trio study of the International Cleft Consortium came from several sources, some to individual investigators and some to a consortium supporting the genome-wide study itself. The consortium for GWAS genotyping and analysis was supported by the National Institute for Dental and Craniofacial Research through U01-DE-018993 (International Consortium to Identify Genes and Interactions Controlling Oral Clefts, 2007–2010; T. H. Beaty, PI). Part of the original recruitment of Norwegian case-parent trios was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Health, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.

APPENDIX: DERIVATION OF THE PARAMETER ESTIMATE FOR GENE-ENVIRONMENT INTERACTIONS

Given an environmental exposure indicator z ∈ {0, 1}, we can rewrite equation 2 to incorporate this variable using parameters βG, βE and βGE as

for unexposed families and as

for exposed families.

By splitting our families into unexposed and exposed groups, we can rewrite our log-likelihood (equation 1) as

To obtain our parameter estimates, we want to solve the two equations:

Defining β(1) = βG + βGE we note that

which means that the equations we need to solve reduce to

Note that this amounts to fitting our main-effect model twice, once on the unexposed families and once on the exposed families. Letting be our parameter estimate for the unexposed families, and be our parameter estimate for the exposed families, we obtain our estimates of βG and βGE as

Footnotes

Supporting Information is available in the online issue at wileyonlinelibrary.com.

REFERENCES

- 1000 Genomes Project Consortium. Durbin RM, Abecasis GR, Altshuler DL, Auton A, Brooks LD, Durbin RM, Gibbs RA, Hurles ME, McVean GA. A map of human genome variation from population-scale sequencing. Nature. 2010;467:1061–1073. doi: 10.1038/nature09534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaty TH, Murray JC, Marazita ML, Munger RG, Ruczinski I, Hetmanski JB, Liang KY, Wu T, Murray T, Fallin MD, Redett RA, Raymond G, Schwender H, Jin SC, Cooper ME, Dunnwald M, Mansilla MA, Leslie E, Bullard S, Lidral AC, Moreno LM, Menezes R, Vieira AR, Petrin A, Wilcox AJ, Lie RT, Jabs EW, Wu-Chou YH, Chen PK, Wang H, Ye X, Huang S, Yeow V, Chong SS, Jee SH, Shi B, Christensen K, Melbye M, Doheny KF, Pugh EW, Ling H, Castilla EE, Czeizel AE, Ma L, Field LL, Brody L, Pangilinan F, Mills JL, Molloy AM, Kirke PN, Scott JM, Scott JM, Arcos-Burgos M, Scott AF. A genome-wide association study of cleft lip with and without cleft palate identifies risk variants near MAFB and ABCA4. Nat Genet. 2010;42:525–529. doi: 10.1038/ng.580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslow N, Day N, Halvorsen K, Prentice R, Sabai C. Estimation of multiple relative risk functions in matched case-control studies. Am J Epidemiol. 1978;108:299–307. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning BL, Browning SR. A unified approach to genotype imputation and haplotype-phase inference for large data sets of trios and unrelated individuals. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;84:210–223. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WM, Abecasis GR. Family-based association tests for genomewide association scans. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:913–926. doi: 10.1086/521580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallin D, Beaty T, Liang KY, Chen W. Power comparisons for genotypic vs. allelic TDT methods with > 2 alleles. Genet Epidemiol. 2002;23:458–461. doi: 10.1002/gepi.10192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International HapMap Consortium A second generation human haplotype map of over 3.1 million SNPs. Nature. 2007;449:851–861. doi: 10.1038/nature06258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Willer C, Sanna S, Abecasis G. Genotype imputation. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2009;10:387–406. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.9.081307.164242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louis TA, Carvalho B, Fallin M, Irizarry R, Li Q, Ruczinski I. Association Tests that Accommodate Genotyping Errors. In: Bernardo JM, Bayarri MJ, Berger JO, Dawid AP, Heckerman D, Smith AFM, West M, editors. Bayesian Statistics. Vol. 9. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 2010. pp. 393–420. [Google Scholar]

- Marchini J, Howie B, Myers S, McVean G, Donnelly P. A new multipoint method for genome-wide association studies by imputation of genotypes. Nat Genet. 2007;39:906–913. doi: 10.1038/ng2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plagnol V, Cooper JD, Todd JA, Clayton DG. A method to address differential bias in genotyping in large-scale association studies. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:759–767. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruim RJ, Welch RP, Sanna S, Teslovich TM, Chines PS, Gliedt TP, Boehnke M, Abecasis GR, Willer CJ. Locuszoom: regional visualization of genome-wide association scan results. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2336–2337. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaid DJ. General score tests for associations of genetic markers with disease using cases and their parents. Genet Epidemiol. 1996;13:423–449. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2272(1996)13:5<423::AID-GEPI1>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaid DJ. Likelihoods and TDT for the case-parents design. Genet Epidemiol. 1999;16:250–260. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2272(1999)16:3<250::AID-GEPI2>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwender H, Taub MA, Beaty TH, Marazita ML, Ruczinski I. Rapid testing of SNPs and gene-environment interactions in case-parent trio data based on exact analytic parameter estimation. Biometrics. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2011.01713.x. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J, Li Y, Abecasis GR, Scheet P. A comparison of approaches to account for uncertainty in analysis of imputed genotypes. Genet Epidemiol. 2011;35:102–110. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.