Abstract

Recently, we showed that E2F7 and E2F8 (E2F7/8) are critical regulators of angiogenesis through transcriptional control of VEGFA in cooperation with HIF.1 Here we investigate the existence of other novel putative angiogenic E2F7/8-HIF targets, and discuss the role of the RB-E2F pathway in regulating angiogenesis during embryonic and tumor development.

Keywords: HIF, E2F, RB, VEGF, hypoxia, angiogenesis, cancer

E2F7/8 function as novel and critical regulators of angiogenesis

Two decades after the identification of E2F1 as the factor through which the Retinoblastoma (RB1/RB) protein controls the adenoviral E2 promoter, the RB-E2F pathway has been proven as a key regulator of cellular proliferation.2,3 Today, eight E2F family members have been cloned, which are generally classified as activators (E2F1–3) or repressors (E2F4–8). The most recently identified E2F members, E2F7 and E2F8 (E2F7/8), are referred to as atypical E2Fs because they harbor two instead of one DNA binding domain and regulate gene transcription independently of DP and RB proteins.2-6 Although E2F factors were long understood as essential regulators of cellular proliferation, recent in vivo studies using gene-targeting knockout strategies showed that E2Fs are dispensable for proliferation. Mice lacking all three activator E2Fs (E2f1–3)7,8 or both atypical E2Fs (E2f7/8)9 die during mid-gestation without any obvious effects on cellular proliferation. These studies indicate that E2F1–3 and E2F7/8 are essential for embryonic survival through control of critical functions other than proliferation. Indeed, combined deletion of the E2f7 and E2f8 genes in mice causes lethality around embryonic day 10.5, resulting from widespread apoptosis and vascular defects.9 Interestingly, although apoptosis was rescued upon additional deletion of E2f1, vascular defects and embryonic lethality (E10.5) were not rescued in these E2f7/8/1 triple knockout mice,9 suggesting that E2F7/8 are essential for angiogenesis during development. In a follow up study we could indeed confirm a critical role for E2F7/8 in angiogenesis: inactivation of E2F7/8 in mice or zebrafish causes disorganized angiogenic sprouting resulting in an unstable and leaky vasculature.1 Mechanistically, we found that E2F7/8 form a transcriptional complex with hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF1) and mediate angiogenesis through control of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGFA) expression,1 a key regulator of vascular development. To our surprise, we found that E2F7/8, although classified as repressors, stimulate VEGFA transcription. This activator role for E2F7/8 in transcription is probably promoter context dependent. In the case of the VEGFA promoter E2F7/8 stimulate transcription because they cooperate with the transcriptional activator HIF and act through a HIF-BS instead of an E2F-BS,1 through which they in general repress transcription.2,3 The importance of the E2F7/8-HIF interaction is furthermore underlined by the observation that similar to E2f7/8 knockout mice, mice lacking Hif1〈, Hif2〈 or Hif® (Arnt) also die around embryonic day 10.5 due to vascular defects.10 Moreover, specific deletion of E2f7/8 in the extra-embryonic trophectoderm results in a poorly formed placental vascular network,11 a phenotype also observed in mice deficient for Hif1〈, Hif2〈 or Hif®.10 Interestingly, both conventional deletion of E2f7/8 as well as trophectoderm (placenta)-specific deletion of E2f7/8 results in embryonic death around embryonic day E10.5, whereas mice are born alive when E2f7/8 are deleted only in the embryo and not in the placenta.11 These data show that regulation of placental development is an essential function of E2F7/8, a function that they likely perform in cooperation with HIF. Furthermore, these in vivo studies also suggest that the vascular defects in the placenta are also responsible for the embryonic lethality observed in Hif−/− mice. The placenta might additionally serve as a suitable model to further explore the molecular mechanism of the E2F7/8-HIF interaction in vivo.

Identifying novel E2F7/8-HIF targets involved in angiogenesis

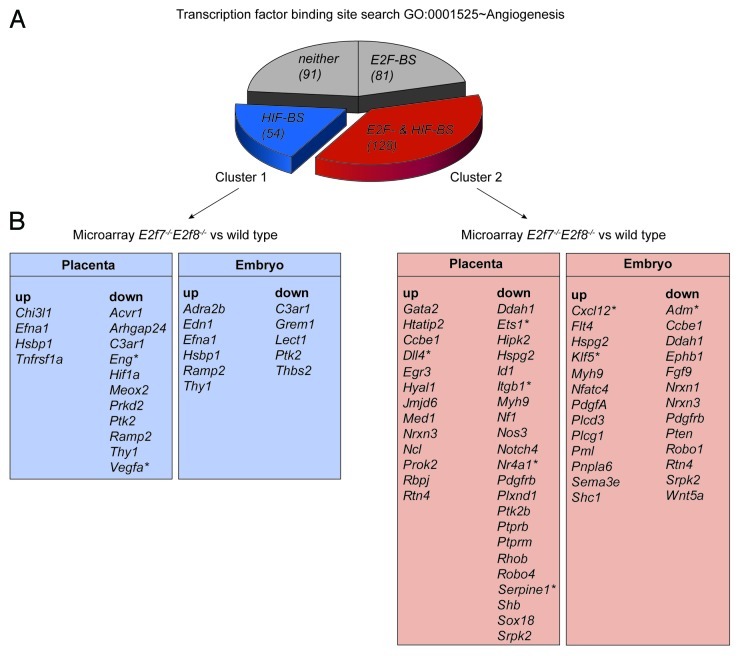

Because the E2F7/8-HIF complex plays an essential role in angiogenesis1 we screened for novel putative E2F7/8-HIF angiogenic targets. We first analyzed the promoters of genes within the GO cluster angiogenesis (AmiGO GO:0001525) for the presence of conserved HIF- and/or E2F-BS with DAVID (Functional Annotation Bioinformatic Microarray Analysis). The GO cluster angiogenesis contains 354 genes of which 54 genes contain only a conserved HIF-BS in their promoter, while 128 have both a conserved HIF- and E2F-BS in their promoter, and 81 genes carry only an E2F-BS in their promoter (Fig. 1A). In addition, functional annotation within DAVID offers the possibility to look at in silico tissue expression, providing additional information whether these genes are expressed in specific tissues/organs (DAVID; UniProt_tissue expression (UPte)). Interestingly, analysis of all 354 genes form the GO angiogenesis showed the 2nd most strong correlation to the placenta (behind the UPte category Plasma), providing support to study angiogenesis not only in the embryo but also in the placenta.

Figure 1.Exploring novel putative angiogenic targets of the E2F7/8-HIF complex. (A) HIF binding site (HIF-BS) and E2F binding site (E2F-BS) analysis in promoters of genes contained by the ontology cluster angiogenesis (AmiGO term GO:0001525, 354 genes). The UCSC TFBS function within the DAVID software was used to search in each of these genes for conserved (between human, mouse and rat) binding sites within a region up to 5kb upstream of the transcription start site. (B) Identification of deregulated angiogenesis transcripts in embryos or placentas lacking E2f7/8. Data analysis was performed on a public data set (GSE30488), using Flexarray 1.6.1. After background correction with RMA, Empirical Bayes estimation (Wright&Simon) was performed. Sox2-Cre; E2f7−/−E2f8−/− embryos were compared with wild type embryos; and Cyp19-Cre; E2f7−/−E2f8−/− placentas with wild type placentas. Gene lists represent transcripts from angiogenesis genes with an adjusted P value < 0.05 vs. wild type, subdivided according to presence of HIF-BS or HIF-BS+E2F-BS as found in (A). Asterisks indicate described HIF target genes.

Next, we used recently published microarray data in which E2f7/8 had been specifically deleted in either the mouse embryo or the placenta,11 to identify E2F7/8-regulated angiogenic genes (Fig. 1B). Because we recently showed that the E2F7/8-HIF complex regulates VEGFA through a HIF-BS,1 we focused our further analysis only on target genes having at least a HIF-BS in their promoter (Fig. 1, cluster 1 and 2). Because E2F7/8 in general repress transcription when bound to an E2F-BS12 we expected to find a higher percentage of E2F7/8 regulated genes to be upregulated in cluster 2 (in which genes contain an E2F-BS besides a HIF-BS in their promoter) compared with cluster 1 genes (in which genes only contain a HIF-BS in their promoter). However, both clusters have a comparable percentage of upregulated genes, suggesting that the presence of an E2F-BS does not seem to be predictive for the mode (up or down) of regulation (Fig. 1B). Instead, we assume HIF to be an important determinant for the repressive or activating transcriptional character of E2F7/8. In the case of cluster 1 genes, E2F7/8 probably depend on the presence of HIF in order to regulate gene expression, as we show for VEGFA.1 However, in the case of cluster 2 genes, E2F7/8 may repress expression in the absence of HIF (through the E2F-BS), whereas the presence of HIF may turn E2F7/8 in transcriptional activators. Furthermore, it must be mentioned that in both cluster 1 and 2 loss of E2f7/8 results in more down- than upregulated genes in the placenta suggesting that the E2F7/8-HIF complex predominantly functions as an activator of angiogenic genes in the placenta. Our analysis also identifies several described HIF targets genes (indicated with an asterisks, Figure 1B), including Vegfa, which is downregulated in the absence of E2F7/8 as we previously reported.1 This strengthens the validity of our approach. Further studies are required to verify that these angiogenic factors are indeed regulated by the HIF-E2F7/8 complex.

RB-E2F factors control angiogenesis through regulation of VEGFA and its receptors

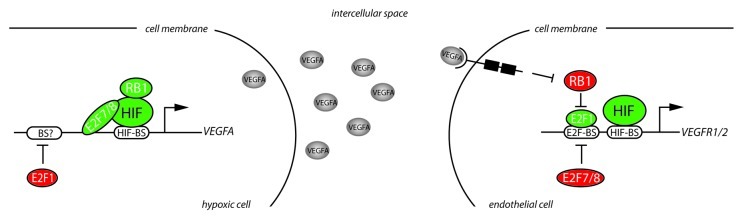

Typical E2F function (E2F1–5) is tightly regulated by the pocket proteins RB1/p105, RBL1/p107 and RBL2/p130. When bound to these pocket proteins, E2Fs act as transcriptional repressors.2,3 An intriguing question that needs to be addressed is whether the RB-E2F pathway in general regulates vascular development and whether such a role would depend on a cooperation with HIF factors. With regard to RB1 the literature indeed suggests that RB1 like E2F7/8 regulates vascular development in cooperation with HIF. Specifically, RB1 has been shown in vitro to stimulate HIF-dependent transcription by forming a direct interaction with HIF,13 like we show for E2F7/8.1 Furthermore, RB1 is enriched on the VEGFA promoter, possibly through its interaction with HIF13 and regulates VEGFA expression.14 In line with the observation that deletion of E2f7/8 or Hif in mice results in vascular defects in the placenta, loss of Rb1 also results in vascular defects in the placenta.15 Deletion of Rb1 in the trophectoderm not only results in a disruption of the labyrinth architecture because of excessive trophoblast proliferation, but also results in a reduced number of fetal capillaries.15 Based on the interaction between RB-HIF and HIF-E2F7/8 and the similar vascular phenotypes in placentas of individual Rb1−/−, Hif−/−, and E2f7/8−/− mice, we suggest that the interaction between RB-E2F and HIF pathway plays an important role in regulating the expression of angiogenic factors in placenta. Although RB1, E2F7/8 and HIF may cooperate on gene transcription in a common transcriptional complex, it is unlikely that RB1 and E2F7/8 directly interact. Namely, unlike E2F1–5, E2F7/8 do not harbor a RB-binding domain.2,3 HIF1, however may facilitate an indirect interaction between E2F7/8 and RB1 because both proteins interact with HIF1〈 through different domains: E2F7/8 bind to the N-terminal 80 amino acids of HIF1〈,1 while RB1 binds to amino acids 530–694.13 E2F7/8 and RB1 may thus regulate angiogenesis as part of shared transcriptional complex through their direct but independent interaction with HIF1 (Fig. 2). Furthermore, E2F7/8 and RB1 may also functionally interact in their control of angiogenesis. Similar to the reported synergistic function of E2F8 and RB1 in controlling erythropoiesis,16 E2F7/8 and RB1 may also synergistically regulate angiogenesis. For example, simultaneous deletion of E2F7/8 and RB1 may result in ectopic activator E2F activity which may lead to deregulation of angiogenic E2F targets such as VEGFA.

Figure 2.RB-E2F factors control angiogenesis through regulation of VEGFA and its receptors. In hypoxic cells HIF proteins stimulate VEGFA expression. RB1 and E2F7/8 have both been reported to interact with HIF and co-stimulate transcriptional activation of VEGFA. E2F1 downregulates VEGFA transcription through a yet unknown mechanism. The VEGFA protein is secreted by hypoxic cells, migrates through the intercellular space and binds to VEGFR2 on endothelial cells which in turn activates a downstream signaling cascade leading to the inactivation (hyper-phosphorylation) of pocket proteins such as RB1. As a result, E2F1 is activated and subsequently stimulates expression of VEGFR1/2, thereby regulating endothelial cell function. E2F7/8 on the other hand repress transcription of VEGFR1/2.

Further support that the RB-E2F pathway controls angiogenesis is provided by in vivo studies using E2f1−/− mice that display enhanced angiogenesis, endothelial cell proliferation and reperfusion in a hind limb ischemia model, resulting from enhanced Vegfa expression.17 Mechanistically, E2F1 was proposed to repress the VEGFA promoter in cooperation with p53 (Tp53),17 although another study reported that E2F1 can also repress VEGFA transcription independent of p53.18 Importantly, recent studies demonstrated that E2Fs not only regulate VEGFA transcription in cells that secrete angiogenic factors, but also regulate expression of VEGF receptors in endothelial cells. Specifically, VEGFA stimulation of endothelial cells results in inactivation (hyperphosphorylation) of RB1 leading to E2F1 induced transcriptional activation of VEGFR1/FLT1 and VEGFR2/KDR (Fig. 2).19 Interestingly, in zebrafish we observed that inactivation of e2f7/8 potently induces the expression of vegfr1/2 in vascular endothelial cells (unpublished observations), suggesting that E2F7/8 also regulate angiogenesis on the level of endothelial cells and that E2F activators and E2F7/8 repressors balance the expression of VEGFR1/2. Notably, VEGFR120 and VEGFR221 have also been described as HIF target genes, raising the possibility that E2F7/8 regulate the expression of these factors in cooperation with HIF. Combined with our observations1 a model emerges in which the E2F7/8-HIF complex induces VEGFA expression in hypoxic cells. Secreted VEGFA subsequently binds to VEGF-receptors on endothelial cells, and stimulates transcription of VEGFR1/2 through activation of E2F1 (Fig. 2). E2Fs may thus function in a feedback loop to control VEGFA signaling in endothelial cells. Together these data suggest that regulation of angiogenesis may be a general function of RB-E2F proteins in which the cooperation with HIF may play an essential role.

A role for RB-E2F factors in regulating tumor angiogenesis

It was recently suggested that RB-E2F factors regulate tumor development independent of their ability to control cell proliferation.2 Regulation of tumor angiogenesis by the RB-E2F pathway presents such an unanticipated E2F function. For example, E2F1 represses neo-angiogenesis in a xenograft tumor model. Specifically, injection of cancer cells into E2f1−/− mice results in more highly vascularized and hemorrhagic tumors compared with wild type mice which was suggested to result from increased Vegfa expression upon deletion of in E2f1.17 Another study also showed that E2F1 repressed tumor angiogenesis by repressing VEGFA expression.18 Interestingly, the ability of E2F1 to either inhibit or promote tumor angiogenesis may depend on the status of p53. Although E2F1 represses VEGFA-induced tumor angiogenesis17,18 possibly in cooperation with wild type p53,17 a transcriptional complex consisting of E2F1 and mutant p53 was reported to stimulate angiogenesis by increased transcription of ID4.22 Together, these studies suggest that in the tumor-microenvironment an E2F1-p53 complex inhibits angiogenesis through decreased VEGFA expression, while in the tumor mutant p53 may cooperate with E2F1 to stimulate angiogenesis.

In addition to E2F1, there is experimental evidence that RB1 also regulates tumor vascularization. Loss of p53, but not Rb1, in the skin results in spontaneous squamous cell carcinomas.23 Interestingly, combinatorial deletion of p53 and Rb1 in the skin accelerates the formation of squamous cell carcinomas and augmented tumor angiogenesis.23 In line with these studies, infection of keratinocytes with the papillomavirus E6 and E7 oncoproteins, which inactivate p53 and RB1, also results in an pro-angiogenic transcriptional response including increased expression of VEGFA.24 Furthermore, Rb1+/− mice develop spontaneously highly vascularized pituitary adenocarcinomas.25 Enhanced Id2 activity in these Rb1-deficient tumors was shown to stimulate tumor angiogenesis by increasing Vegfa expression.25 Finally, the role of RB1 in in regulating tumor angiogenesis can also be regulated through its interaction with the RAF1 kinase. RAF1 directly binds and inhibits RB1, while specific disruption of this interaction significantly reduces tumor angiogenesis.26,27 Why RB1 stimulates angiogenesis in the placenta but represses angiogenesis during tumor development is currently unclear. In the placenta, the prominent pro-angiogenic activity of HIF may switch RB1 into a pro-angiogenic factor through their direct interaction. In addition, loss of RB1 in the placenta may also activate E2F1, leading to E2F1-induced inhibition of angiogenesis. In tumors the angiogenic function of RB1 may also be determined by HIF. In hypoxic tumors HIF may switch RB1 into a pro-angiogenic factor, whereas in more oxygenated tumors RB1 could functions as an anti-angiogenic factor. Alternatively, deletion of RB1 in tumors could also lead to ectopic E2F1 activity which may stimulate angiogenesis in cooperation with mutant P53,22 as mentioned above.

These studies show a role for RB1 and E2F1 in tumor angiogenesis. It will be interesting to investigate under which conditions they function as pro- or anti-angiogenic factors, and if their capacity to regulate angiogenesis is shared by other RB or E2F family members, especially E2F7/8. Because hypoxia is a hallmark of solid tumor development and HIF factors are critical for promoting tumor angiogenesis,28-30 we expect that E2F7/8 and RB1 regulate tumor angiogenesis through their interaction with HIF.

Concluding remarks and future outlook

There is strong evidence that RB and E2F factors regulate normal and tumor angiogenesis. Future studies are required to determine if and how the RB-E2F pathway regulates the formation of blood vessels in general, and to which extend they depend on HIF for this function. Downstream of RB and E2F factors a major pathway begins to emerge. The above mentioned studies clearly identify the VEGFA signaling pathway through which E2F7/8, E2F1 and RB1 control angiogenesis. However, future experiments will determine if the identified putative E2F7/8-HIF angiogenic targets (Fig. 1B) present novel downstream targets through which E2f7/8, and possibly the RB-E2F pathway in general, controls angiogenesis during embryonic and tumor development.

Acknowledgments

WJB is supported by grants from AICR and the Dutch Cancer Society (KWF).

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/transcription/article/23680

References

- 1.Weijts BG, Bakker WJ, Cornelissen PW, Liang KH, Schaftenaar FH, Westendorp B, et al. E2F7 and E2F8 promote angiogenesis through transcriptional activation of VEGFA in cooperation with HIF1. EMBO J. 2012;31:3871–84. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen HZ, Tsai SY, Leone G. Emerging roles of E2Fs in cancer: an exit from cell cycle control. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:785–97. doi: 10.1038/nrc2696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van den Heuvel S, Dyson NJ. Conserved functions of the pRB and E2F families. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:713–24. doi: 10.1038/nrm2469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Bruin A, Maiti B, Jakoi L, Timmers C, Buerki R, Leone G. Identification and characterization of E2F7, a novel mammalian E2F family member capable of blocking cellular proliferation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:42041–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308105200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maiti B, Li J, de Bruin A, Gordon F, Timmers C, Opavsky R, et al. Cloning and characterization of mouse E2F8, a novel mammalian E2F family member capable of blocking cellular proliferation. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:18211–20. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501410200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Di Stefano L, Jensen MR, Helin K. E2F7, a novel E2F featuring DP-independent repression of a subset of E2F-regulated genes. EMBO J. 2003;22:6289–98. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen D, Pacal M, Wenzel P, Knoepfler PS, Leone G, Bremner R. Division and apoptosis of E2f-deficient retinal progenitors. Nature. 2009;462:925–9. doi: 10.1038/nature08544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chong JL, Wenzel PL, Sáenz-Robles MT, Nair V, Ferrey A, Hagan JP, et al. E2f1-3 switch from activators in progenitor cells to repressors in differentiating cells. Nature. 2009;462:930–4. doi: 10.1038/nature08677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li J, Ran C, Li E, Gordon F, Comstock G, Siddiqui H, et al. Synergistic function of E2F7 and E2F8 is essential for cell survival and embryonic development. Dev Cell. 2008;14:62–75. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dunwoodie SL. The role of hypoxia in development of the Mammalian embryo. Dev Cell. 2009;17:755–73. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ouseph MM, Li J, Chen HZ, Pécot T, Wenzel P, Thompson JC, et al. Atypical E2F repressors and activators coordinate placental development. Dev Cell. 2012;22:849–62. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Westendorp B, Mokry M, Groot Koerkamp MJ, Holstege FC, Cuppen E, de Bruin A. E2F7 represses a network of oscillating cell cycle genes to control S-phase progression. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:3511–23. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Budde A, Schneiderhan-Marra N, Petersen G, Brüne B. Retinoblastoma susceptibility gene product pRB activates hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) Oncogene. 2005;24:1802–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tracy K, Dibling BC, Spike BT, Knabb JR, Schumacker P, Macleod KF. BNIP3 is an RB/E2F target gene required for hypoxia-induced autophagy. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:6229–42. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02246-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu L, de Bruin A, Saavedra HI, Starovic M, Trimboli A, Yang Y, et al. Extra-embryonic function of Rb is essential for embryonic development and viability. Nature. 2003;421:942–7. doi: 10.1038/nature01417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu T, Ghazaryan S, Sy C, Wiedmeyer C, Chang V, Wu L. Concomitant inactivation of Rb and E2f8 in hematopoietic stem cells synergizes to induce severe anemia. Blood. 2012;119:4532–42. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-10-388231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qin G, Kishore R, Dolan CM, Silver M, Wecker A, Luedemann CN, et al. Cell cycle regulator E2F1 modulates angiogenesis via p53-dependent transcriptional control of VEGF. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:11015–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509533103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Merdzhanova G, Gout S, Keramidas M, Edmond V, Coll JL, Brambilla C, et al. The transcription factor E2F1 and the SR protein SC35 control the ratio of pro-angiogenic versus antiangiogenic isoforms of vascular endothelial growth factor-A to inhibit neovascularization in vivo. Oncogene. 2010;29:5392–403. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pillai S, Kovacs M, Chellappan S. Regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor receptors by Rb and E2F1: role of acetylation. Cancer Res. 2010;70:4931–40. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gerber HP, Condorelli F, Park J, Ferrara N. Differential transcriptional regulation of the two vascular endothelial growth factor receptor genes. Flt-1, but not Flk-1/KDR, is up-regulated by hypoxia. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:23659–67. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.38.23659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kappel A, Rönicke V, Damert A, Flamme I, Risau W, Breier G. Identification of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor-2 (Flk-1) promoter/enhancer sequences sufficient for angioblast and endothelial cell-specific transcription in transgenic mice. Blood. 1999;93:4284–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fontemaggi G, Dell’Orso S, Trisciuoglio D, Shay T, Melucci E, Fazi F, et al. The execution of the transcriptional axis mutant p53, E2F1 and ID4 promotes tumor neo-angiogenesis. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:1086–93. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martínez-Cruz AB, Santos M, Lara MF, Segrelles C, Ruiz S, Moral M, et al. Spontaneous squamous cell carcinoma induced by the somatic inactivation of retinoblastoma and Trp53 tumor suppressors. Cancer Res. 2008;68:683–92. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-3049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Toussaint-Smith E, Donner DB, Roman A. Expression of human papillomavirus type 16 E6 and E7 oncoproteins in primary foreskin keratinocytes is sufficient to alter the expression of angiogenic factors. Oncogene. 2004;23:2988–95. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lasorella A, Rothschild G, Yokota Y, Russell RG, Iavarone A. Id2 mediates tumor initiation, proliferation, and angiogenesis in Rb mutant mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:3563–74. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.9.3563-3574.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kinkade R, Dasgupta P, Carie A, Pernazza D, Carless M, Pillai S, et al. A small molecule disruptor of Rb/Raf-1 interaction inhibits cell proliferation, angiogenesis, and growth of human tumor xenografts in nude mice. Cancer Res. 2008;68:3810–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dasgupta P, Sun J, Wang S, Fusaro G, Betts V, Padmanabhan J, et al. Disruption of the Rb--Raf-1 interaction inhibits tumor growth and angiogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:9527–41. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.21.9527-9541.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liao D, Johnson RS. Hypoxia: a key regulator of angiogenesis in cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2007;26:281–90. doi: 10.1007/s10555-007-9066-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keith B, Johnson RS, Simon MC. HIF1α and HIF2α: sibling rivalry in hypoxic tumour growth and progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:9–22. doi: 10.1038/nrc3183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Semenza GL. Targeting HIF-1 for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:721–32. doi: 10.1038/nrc1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]