Abstract

Transcription elongation is now recognized as an important mechanism of gene regulation in eukaryotes. A large number of genes undergo an early step in transcription that is rate limiting for expression. Genome-wide studies showing that RNA polymerase II accumulates to high densities near the promoters of many genes has led to the idea that promoter-proximal pausing of transcription is a widespread, rate-limiting step in early elongation. Recent evidence suggests that much of this paused RNA polymerase II is competent for transcription elongation. Here, we discuss recent studies suggesting that RNA polymerase II that accumulates nearby the promoter of a subset of genes is undergoing premature termination of transcription.

Keywords: transcription, RNAP II pausing, premature termination, Xrn2, microprocessor

Introduction

For many years, it was thought that transcription was largely controlled at the step of initiation through the regulated formation of the pre-initiation complex or PIC. However, a few genes clearly did not fit this mold since overwhelming evidence indicated that their expression was regulated at an early step in transcriptional elongation. Such genes, including c-myc, Hsp70 and HIV-1, were thought to be somewhat atypical.1-3 However, the advent of genome-wide approaches to the analysis of transcription gave rise to a fundamental change in the way molecular biologists consider the regulation of gene expression. Early ChIP-seq analyses were the first to suggest that the conventional view of transcriptional regulation may be incomplete. These analyses revealed the somewhat surprising finding that the majority of genes showed an accumulation of RNA polymerase II (RNAP II) close to the promoter, similar to that observed for c-Myc, Hsp70 and HIV-1.4-6 Other techniques that are able to quantify the transcriptome also brought astounding new information. RNA-seq revealed that the majority of the genome is transcribed, a finding that further confounded conventional models of transcriptional regulation.7-10 Using global run-on sequencing (GRO-seq), the Lis lab further showed that the majority of promoter-proximal RNAP II molecules are competent to undergo elongation.8 Indeed, these data indicated that detergent-sensitive factor(s) retain RNAP II in a ‘paused’ state near the promoter. More recent studies have used refined techniques with higher resolution to clarify the picture of RNAP II pausing at promoter regions. The recently described precision run-on and sequencing (PRO-seq) technique has revealed distinct RNAP II pausing patterns.11 Based on the pause sites mapped by PRO-seq, paused RNAP II can be classified into two quite separate groups. At so-called ‘prox’ genes, RNAP II pauses sharply around a site that is quite close to the TSS. At ‘dist’ genes, on the other hand, RNAP II pause sites are dispersed over a wider span that starts further away from the TSS. Promoter-proximal pausing of RNAP II has been the subject of several excellent reviews12,13 and will not be discussed in detail here. At this juncture then, there is compelling data to indicate that the majority of genes are regulated by a rate-limiting step that occurs during the first 100 nucleotides of transcription.

As might be expected, these remarkable findings have raised many questions that remain to be answered. One such question is the fate of paused RNAP II: does RNAP II transcribe 50 to 100 nucleotides and become stably ‘paused’ awaiting the appropriate signal to continue into elongation? Or is the promoter-proximal region a hive of RNAP II activity, where RNAP II molecules that remain in a paused state are subjected to premature termination, and a new cycle of transcription initiates until the prevailing conditions allow RNAP II to escape into elongation?

Two recent studies have provided evidence that promoter-proximal accumulation of RNAP II observed at some genes is due to premature termination of transcription.14,15 These findings indicate that RNAP II that accumulates near promoters of a subset of genes is undergoing termination. Although the mechanisms identified by these studies are not the same, certain features are shared, which suggests that the mechanism used at a specific gene may depend on its inherent underlying features.

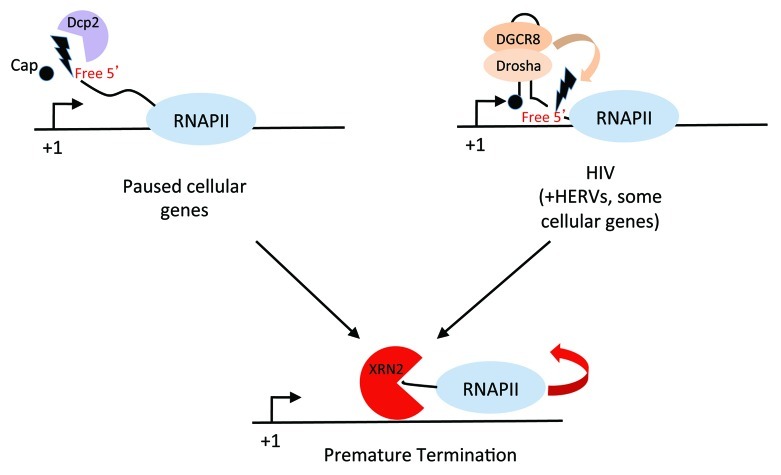

The ‘Decapping’ model of Premature Termination of Transcription

Prompted by the surprising interaction between the 5′ to 3′ exoribonuclease ‘torpedo’, Xrn2, mRNA decapping factors, Edc3, Dcp1a and Dcp1b, and the termination factor, TTF2, the Bentley lab investigated a possible role for these factors in premature termination of transcription.14 ChIP-seq analysis revealed that these factors localized at the transcription start sites (TSS) of many genes. At genes showing a 5′ peak of RNAP II, loss of these factors following RNAi altered the profile of RNAP II association across the gene. The peak of RNAP II at the TSS was diminished while RNAP II association with more distal sites, either upstream or downstream of the TSS, was increased. These results suggested a model in which decapping of the nascent transcript provides an entry site for the torpedo Xrn2, which, together with the ATPase TTF2, would chase and eventually dislodge the early elongating RNAP II, resulting in premature termination of transcription.

One important question that these findings raise is how this process might be regulated. Generalized decapping of nascent transcripts should not occur; the consequences of such a phenomenon would be catastrophic for gene expression. Decapping is known to occur in the privileged environment of cytoplasmic P-bodies that are a storage space and/or junkyard for cellular mRNAs.16 However, decapping factors are also found in the nucleus.17 How then is nuclear decapping activity controlled? Do nuclear decapping factors become activated under specific conditions? Are nuclear mRNAs protected somehow from decapping? Decapping probably occurs very soon after the initiation of transcription, since most RNAP II molecules have terminated close to the promoter. What is the early signal that initiates the cascade of decapping coupled to termination? The nuclear cap binding complex (CBC), consisting of CBC20 and CBC80, binds to the 5′ cap structure to protect it from nuclease digestion. Both capping and CBC binding are early events that occur co-transcriptionally. Interestingly, CBC physically interacts with kinase subunit of P-TEFb and affects elongation of transcription in yeast and humans.18,19 Thus, an early transcriptional defect may result in failure to recruit CBC, thereby exposing the 5′ cap structure to decapping and exonuclease digestion. It will be interesting to investigate the role of CBC in decapping-initiated premature termination.

In what sequence are decapping factors, termination factors and Xrn2 recruited to paused genes? Interestingly, Xrn2 appears to be recruited to the 5′ end of GAPDH independently of decapping factors since knockdown of Dcp2 did not affect recruitment of Xrn2.14 This could imply that Xrn2 may be constitutively associated with the elongating RNAP II complex, as part of a RNA surveillance mechanism that has been described for the nuclear exosome, a 3′ to 5′ exoribonuclease complex.20 Its activity would only be unleashed in the presence of an RNA molecule that possesses an uncapped 5′ end generated by cleavage, as occurs during 3′ end termination, or by decapping.

How does the ‘decapping’ model of premature termination explain the existence of small TSS RNAs? Presumably, such RNAs would likely correspond to intermediates produced during premature termination. A proportion of these species are known to be stabilized by knockdown of nuclear exosome catalytic subunit Rrp6,9 which may slow down the degradation of small unprotected RNAs sufficiently to allow detection by high throughput sequencing methods.

The ‘Microprocessor’ Model of Premature Termination

Premature termination of transcription has recently been proposed to resolve the status of paused RNAP II, notably at the HIV-1 promoter, albeit through a rather different mechanism than decapping-coupled termination.15 HIV-1, like c-myc and Hsp genes, has long been known to be regulated by promoter-proximal pausing.2 Indeed, the HIV-1 promoter has served as a useful model to study RNAP II pausing. The effects of negative elongation factors, DSIF and NELF, and positive elongation factor, P-TEFb, have been investigated using this model. In the absence of the viral transactivator, Tat, transcription from the HIV-1 promoter results in the synthesis of a 59 nt stable stem loop structure known as TAR (Transactivation Response) that is critical for viral transcription. Tat relieves the elongation block by binding to TAR RNA as part of a complex that contains multiple elongation factors, most notably P-TEFb.21-24 Thus, Tat is a rather atypical transcription factor since it does not act through binding to DNA elements, but by binding to RNA. In this respect, Tat is more analogous to prokaryotic anti-termination factors than eukaryotic transcription factors.25

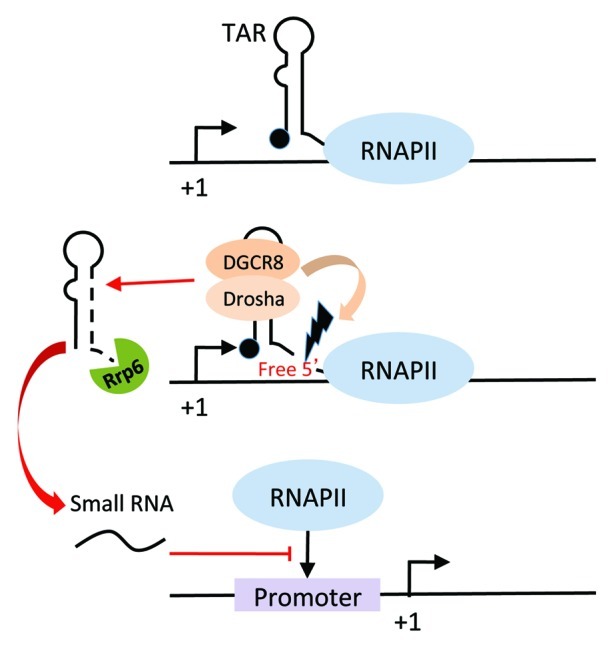

The resemblance between the stem loop structure of TAR and pre-miRNA hairpins prompted Wagschal et al. to address whether TAR might be a substrate for cleavage by the nuclear endoribonuclease complex Microprocessor, which consists minimally of the RNase III Drosha and a RNA binding subunit Dgcr8, and is required for the regulation of mature miRNA abundance.26 Microprocessor was associated with the HIV-1 promoter proximal region in LTR-containing cells that synthesize TAR RNA. Loss of Microprocessor promoted HIV-1 transcription, as measured by RT-q-PCR of transcripts, nuclear run-on transcription assays as well as ChIP for RNAP II. The increase in HIV-1 transcription was dependent on the catalytic activity of Drosha. Thus, it appeared that Microprocessor recognizes and cleaves the stem loop structure of TAR. Does this cleavage create an internal binding site for Xrn2 and the premature termination machinery? Consistent with this idea, recruitment of Xrn2 and the RNA/DNA helicase Senataxin (Setx), which has been implicated in termination of transcription,27,28 were diminished in the absence of Drosha. These data suggested a model in which the inherent structure of the nascent transcript can recruit Microprocessor to initiate premature termination of transcription. This mechanism also appears to extend to human endogenous retroviruses and a subset of cellular genes.15 Thus, this study identified a novel function for Microprocessor in the control of gene expression that is independent of its function in RNA interference. In support of this idea, Microprocessor has previously been shown to associate with genes that do not contain any known miRNA,29 and HITS-CLIP technology was recently used to show that Dgcr8 interacts with many non-miRNA stem loop-containing cellular RNAs.30 However, the full repertoire of cellular genes regulated by Microprocessor-initiated premature termination is currently not known. RNAP II is known to accumulate near the promoter regions of signal-responsive genes, presumably to maintain a state of readiness to respond to stimuli.31 Whether the expression of such genes is controlled by Microprocessor-induced premature termination will be interesting to determine.

Since the TAR stem-loop is present at the 5′ end of all HIV-1 transcripts, how can cleavage by Microprocessor be turned off to allow gene expression? As noted above, the viral transactivator binds to TAR RNA. Indeed, binding of Microprocessor and Tat appear to be mutually exclusive. Either the factors compete for TAR binding, or binding of Tat distorts the structure of TAR, in a manner akin to bacterial anti-terminator factors,25,32 such that it is no longer recognized by Microprocessor. In the case of cellular genes, RNA binding proteins, many of which are intrinsically involved in transcription, may perform this function. Further work is needed to address this issue.

Discussion and Conclusions

Thus, two pathways of premature termination of transcription have been described recently that may explain the accumulation of RNAP II near the TSS of a subset of genes. Mechanistically, they show certain similarities, but also clear differences. The common point between the two pathways is that termination occurs after entry of the torpedo Xrn2 and associated factors. The major difference between the pathways is that the entry point for Xrn2 is not the same. In the ‘decapping’ model, entry is gained by removal of the protective 5′ cap structure, which allows Xrn2 to degrade the ongoing transcript from the +1 position. In the ‘Microprocessor’ model, the entry site for Xrn2 is internal, probably slightly downstream of the stem loop structure. A second major difference between these mechanisms is that, in the ‘decapping’ model, the nascent transcript will eventually be completely degraded by Xrn2 whereas in the ‘Microprocessor’ model, the stem loop structure is excised and potentially conserved or further processed. Indeed, TAR RNA is further processed by the 3′ to 5′ RNase, Rrp6. The final processing product, 19 nt in length, can be detected in LTR-containing cells in equilibrium with 59 nt TAR RNA. Loss of Rrp6 shifted the balance toward full-length TAR, resulting in reduced amounts of 19 nt small TAR RNA.15 What then is the function of small TAR RNA? Why is it conserved? Exogenous addition of small TAR RNA further repressed HIV-1 transcription while loss of Rrp6 dramatically enhanced it.15 Thus, it appears that small TAR RNA may feed into a transcriptionally repressive mechanism that keeps transcription from the HIV-1 promoter at a low level, possibly to allow the cleavage/termination pathway to act on the initiated transcripts. The mechanistic details of this pathway still need to be resolved, but it hints at a more complex, multifaceted mechanism of gene regulation in operation at certain genes.

In all likelihood, both mechanisms of termination operate in the nucleus to control gene expression. The specific requirements for each pathway may dictate their repertoire of genes. For example, the ‘Microprocessor’ pathway depends on an obligatory stem loop structure present in the mRNA, which would probably be unfavorable for the ‘decapping’ pathway since stable stem loop structures are difficult substrates for exonucleases.33 Both pathways of premature termination probably contribute to the accumulation of RNAP II detected by ChIP-seq as well as the diversity of small TSS RNAs. Thus, the recent reports that premature termination of transcription resolves paused RNAP II at a subset of genes brings us a step closer to understanding gene regulation in humans, a subject that will undoubtedly continue to fascinate molecular biologists in the future.

AUTHOR: Please add in-text citation for Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1. Schematic diagram depicting two recently described pathways of premature termination. In the ‘decapping’ model, shown at left, premature termination is initiated by removal of the 5′ cap structure of nascent transcripts by decapping factors, Dcp1a and Dcp2. The 5′ monophosphate end of the transcript becomes a substrate for the ‘torpedo’ Xrn2, which degrades the ongoing transcript until RNAP II becomes dislodged, possibly by the termination factor, TTF2. A new cycle of transcription is then initiated. In the ‘Microprocessor’ model, shown at right, premature termination of HIV-1 transcription is initiated by an internal cleavage mediated by the nuclear endoribonuclease complex, Microprocessor, consisting of RNase III, Drosha, and RNA binding subunit, Dgcr8. As in the ‘decapping’ model, the cleavage site creates a 5′ monophosphate end that is targeted by Xrn2, which together with the RNA/DNA helicase, Setx, induces premature termination of transcription.

Figure 2. Schematic diagram depicting Rrp6-dependent processing of the 5′ product following Microprocessor cleavage. Cleavage by Microprocessor generates a short transcript with a free 3′ end that can be recognized by the 3′ to 5′ exoribonuclease, Rrp6. Processing products approximately 19–20 nt in length, whose abundance depends on Rrp6, can be detected in LTR-containing cells. These small RNAs can further repress HIV-1 transcription through mechanisms that remain unknown. Restrained transcription may provide the opportunity for Microprocessor to act on newly folded nascent transcripts.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the ERC (250333) and FRM “équipe labéllisée” to MB and ANRS and Sidaction to RK.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/transcription/article/24148

References

- 1.Bentley DL, Groudine M. A block to elongation is largely responsible for decreased transcription of c-myc in differentiated HL60 cells. Nature. 1986;321:702–6. doi: 10.1038/321702a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muesing MA, Smith DH, Capon DJ. Regulation of mRNA accumulation by a human immunodeficiency virus trans-activator protein. Cell. 1987;48:691–701. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90247-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rougvie AE, Lis JT. The RNA polymerase II molecule at the 5′ end of the uninduced hsp70 gene of D. melanogaster is transcriptionally engaged. Cell. 1988;54:795–804. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(88)91087-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guenther MG, Levine SS, Boyer LA, Jaenisch R, Young RA. A chromatin landmark and transcription initiation at most promoters in human cells. Cell. 2007;130:77–88. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muse GW, Gilchrist DA, Nechaev S, Shah R, Parker JS, Grissom SF, et al. RNA polymerase is poised for activation across the genome. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1507–11. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zeitlinger J, Stark A, Kellis M, Hong JW, Nechaev S, Adelman K, et al. RNA polymerase stalling at developmental control genes in the Drosophila melanogaster embryo. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1512–6. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Affymetrix ENCODE Transcriptome Project. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory ENCODE Transcriptome Project Post-transcriptional processing generates a diversity of 5′-modified long and short RNAs. Nature. 2009;457:1028–32. doi: 10.1038/nature07759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Core LJ, Waterfall JJ, Lis JT. Nascent RNA sequencing reveals widespread pausing and divergent initiation at human promoters. Science. 2008;322:1845–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1162228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Preker P, Nielsen J, Kammler S, Lykke-Andersen S, Christensen MS, Mapendano CK, et al. RNA exosome depletion reveals transcription upstream of active human promoters. Science. 2008;322:1851–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1164096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seila AC, Calabrese JM, Levine SS, Yeo GW, Rahl PB, Flynn RA, et al. Divergent transcription from active promoters. Science. 2008;322:1849–51. doi: 10.1126/science.1162253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kwak H, Fuda NJ, Core LJ, Lis JT. Precise maps of RNA polymerase reveal how promoters direct initiation and pausing. Science. 2013;339:950–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1229386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adelman K, Lis JT. Promoter-proximal pausing of RNA polymerase II: emerging roles in metazoans. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:720–31. doi: 10.1038/nrg3293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nechaev S, Adelman K. Pol II waiting in the starting gates: Regulating the transition from transcription initiation into productive elongation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1809:34–45. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2010.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brannan K, Kim H, Erickson B, Glover-Cutter K, Kim S, Fong N, et al. mRNA decapping factors and the exonuclease Xrn2 function in widespread premature termination of RNA polymerase II transcription. Mol Cell. 2012;46:311–24. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wagschal A, Rousset E, Basavarajaiah P, Contreras X, Harwig A, Laurent-Chabalier S, et al. Microprocessor, Setx, Xrn2, and Rrp6 co-operate to induce premature termination of transcription by RNAPII. Cell. 2012;150:1147–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kulkarni M, Ozgur S, Stoecklin G. On track with P-bodies. Biochem Soc Trans. 2010;38:242–51. doi: 10.1042/BST0380242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song MG, Li Y, Kiledjian M. Multiple mRNA decapping enzymes in mammalian cells. Mol Cell. 2010;40:423–32. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hossain MA, Chung C, Pradhan SK, Johnson TL. The Yeast Cap Binding Complex Modulates Transcription Factor Recruitment and Establishes Proper Histone H3K36 Trimethylation during Active Transcription. Mol Cell Biol. 2013;33:785–99. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00947-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lenasi T, Peterlin BM, Barboric M. Cap-binding protein complex links pre-mRNA capping to transcription elongation and alternative splicing through positive transcription elongation factor b (P-TEFb) J Biol Chem. 2011;286:22758–68. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.235077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andrulis ED, Werner J, Nazarian A, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Lis JT. The RNA processing exosome is linked to elongating RNA polymerase II in Drosophila. Nature. 2002;420:837–41. doi: 10.1038/nature01181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.He N, Liu M, Hsu J, Xue Y, Chou S, Burlingame A, et al. HIV-1 Tat and host AFF4 recruit two transcription elongation factors into a bifunctional complex for coordinated activation of HIV-1 transcription. Mol Cell. 2010;38:428–38. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mancebo HS, Lee G, Flygare J, Tomassini J, Luu P, Zhu Y, et al. P-TEFb kinase is required for HIV Tat transcriptional activation in vivo and in vitro. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2633–44. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.20.2633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sobhian B, Laguette N, Yatim A, Nakamura M, Levy Y, Kiernan R, et al. HIV-1 Tat assembles a multifunctional transcription elongation complex and stably associates with the 7SK snRNP. Mol Cell. 2010;38:439–51. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wei P, Garber ME, Fang SM, Fischer WH, Jones KA. A novel CDK9-associated C-type cyclin interacts directly with HIV-1 Tat and mediates its high-affinity, loop-specific binding to TAR RNA. Cell. 1998;92:451–62. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80939-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Landick R. The regulatory roles and mechanism of transcriptional pausing. Biochem Soc Trans. 2006;34:1062–6. doi: 10.1042/BST0341062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Han J, Lee Y, Yeom KH, Nam JW, Heo I, Rhee JK, et al. Molecular basis for the recognition of primary microRNAs by the Drosha-DGCR8 complex. Cell. 2006;125:887–901. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Skourti-Stathaki K, Proudfoot NJ, Gromak N. Human senataxin resolves RNA/DNA hybrids formed at transcriptional pause sites to promote Xrn2-dependent termination. Mol Cell. 2011;42:794–805. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steinmetz EJ, Warren CL, Kuehner JN, Panbehi B, Ansari AZ, Brow DA. Genome-wide distribution of yeast RNA polymerase II and its control by Sen1 helicase. Mol Cell. 2006;24:735–46. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Han J, Pedersen JS, Kwon SC, Belair CD, Kim YK, Yeom KH, et al. Posttranscriptional crossregulation between Drosha and DGCR8. Cell. 2009;136:75–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Macias S, Plass M, Stajuda A, Michlewski G, Eyras E, Cáceres JF. DGCR8 HITS-CLIP reveals novel functions for the Microprocessor. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19:760–6. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gilchrist DA, Fromm G, dos Santos G, Pham LN, McDaniel IE, Burkholder A, et al. Regulating the regulators: the pervasive effects of Pol II pausing on stimulus-responsive gene networks. Genes Dev. 2012;26:933–44. doi: 10.1101/gad.187781.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nudler E, Gottesman ME. Transcription termination and anti-termination in E. coli. Genes Cells. 2002;7:755–68. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2002.00563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Houseley J, Tollervey D. The many pathways of RNA degradation. Cell. 2009;136:763–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]