Abstract

AIM: To evaluate the association between acid suppressive drug use and the development of gastric cancer.

METHODS: A systematic search of relevant studies that were published through June 2012 was conducted using the MEDLINE (PubMed), EMBASE, and Cochrane Library databases. The search included observational studies on the use of histamine 2-receptor antagonists (H2RAs) or proton pump inhibitors and the associated risk of gastric cancer, which was measured using the adjusted odds ratio (OR) or the relative risk and 95%CI. An independent extraction was performed by two of the authors, and a consensus was reached.

RESULTS: Of 4595 screened articles, 11 observational studies (n = 94558) with 5980 gastric cancer patients were included in the final analyses. When all the studies were pooled, acid suppressive drug use was associated with an increased risk of gastric cancer risk (adjusted OR = 1.42; 95%CI: 1.29-1.56, I2 = 48.9%, P = 0.034). The overall risk of gastric cancer increased among H2RA users (adjusted OR = 1.40; 95%CI: 1.24-1.59, I2 = 59.5%, P = 0.008) and PPI users (adjusted OR = 1.39; 95%CI: 1.19-1.64, I2 = 0.0%, P = 0.377).

CONCLUSION: Acid suppressive drugs are associated with an increased risk of gastric cancer. Further studies are needed to test the effect of acid suppressive drugs on gastric cancer.

Keywords: H2-receptor antagonists, Proton pump inhibitors, Gastric cancer, Meta-analysis

INTRODUCTION

Acid suppressive drugs were the second most prescribed medication worldwide in 2005. Histamine 2-receptor antagonists (H2RAs) and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) were widely used for the treatment of peptic ulcers, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), and other benign conditions of the stomach, esophagus, and duodenum[1-4]. PPIs were one of the most commonly prescribed medications by primary physicians and are frequently used over the long term.

The safety of these drugs and their potential adverse effects is of great importance to public health. Several case reports suggested that acid suppressive drugs may increase the occurrence of gastric polyps or cancer[5-13], and several epidemiological studies have evaluated the association between long-term gastric acid suppression and the risk of gastrointestinal neoplasms. Several researchers have proposed that acid suppressive drugs may suppress gastric acid secretion and interfere with bacterial growth and nitrosamine formation[14-16]. In addition, the reduction of gastric acid secretion with acid suppressive drugs can lead to hypergastrinemia[17,18], which has been identified as a possible risk factor for gastric polyps and gastric and colonic carcinomas[19-22]. However, those findings are contradictory: several studies have found an increased risk of gastric cancer among acid suppressive drug users[23-25], whereas other studies found no evidence of an increased risk[26-28]. To date, no systematic meta-analysis has been published on this topic.

Therefore, in this study, we sought to investigate the association between the use of acid suppressive drugs and the risk of gastric cancer via a meta-analysis of cohort studies and case-control studies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data sources and searches

Our review followed the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines[29]. We performed our search in MEDLINE (PubMed) (inception to June 2012), EMBASE (inception to June 2012), and the Cochrane Library (inception to June 2012) using common key words regarding acid suppression and gastric cancer in case-control studies, cohort studies, and randomized controlled trials (RCTs). However, there were no RCTs among the search results that satisfied our inclusion criteria.

In addition, we searched the bibliographies of relevant articles to identify additional studies of interest. For the studies that did not directly report the association between the use of acid suppressive drugs and gastric cancer incidence, we contacted the authors in the field for any unpublished data. However, the authors did not have any available data to use in our meta-analysis. We used the following keywords in the literature search: “histamine receptor antagonist”, “H2 receptor antagonist”, “cimetidine”, “ranitidine”, “famotidine”, “nizatidine”, “proton pump inhibitor”, “proton pumps”, “omeprazole”, “nexium”, “lansoprazole”, “rabeprazole”, “pantoprazole”, or “esomeprazole” for the exposure factors and “stomach cancer”, “stomach neoplasia”, “gastric cancer”, “gastric neoplasia”, “stomach neoplasm” or “gastric neoplasm” for the outcome factors.

Study selection and data extraction

We included case-control studies and cohort studies that investigated the association between acid suppressive drug use and gastric cancer risk, which reported an adjusted odds ratio (OR) or relative risk (RR) and the corresponding 95%CI. We only selected articles that were written in English and excluded studies with no available data for outcome measures.

All the studies that were retrieved from the databases and bibliographies were independently evaluated by two authors of this paper (Ahn JS and Eom CS). Of the articles that were found in the three databases, duplicate articles and articles that did not meet the selection criteria were excluded. We extracted the following data from the remaining studies: the study names (first author), the year of publication, the country of publication, the study design, the study period, the population characteristics, the type of drugs, the adjusted OR or RR with a 95%CI:the study quality, and the adjustment. The data abstraction and the study selection were performed in duplicate.

Quality assessment

We assessed the methodological quality of the included studies using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for the case-control and cohort studies in the meta-analysis[30]. The NOS is comprehensive and has been partially validated for assessing the quality of non-randomized studies in meta-analyses. The NOS is based on the following three broad subscales: the selection of the study groups (4 items), the comparability of the groups (1 item), and the ascertainment of the exposure and the outcome of interest for case-control studies and cohort studies, respectively (3 items). A “star system” (a score range from 0-9) has been developed for quality assessment. Each study can be awarded a maximum of one star for each numbered item within the selection and exposure categories, whereas a maximum of two stars can be assigned for comparability. In this study, we considered a study that was awarded 7 or more stars as a high-quality study because standard criteria have not been established.

Statistical analysis

The outcome of the meta-analysis was the risk of gastric cancer. We used the adjusted data (adjusted OR or RR with a 95%CI) for the meta-analysis. In addition, we conducted subgroup analyses by type of study design (case-control studies vs cohort studies), type of acid suppressive drugs (H2RAs vs PPIs), duration of acid suppressive drug use (within 5 years vs more than 5 years), location of gastric cancer (gastroesophageal junction, cardia, or non-cardia), and study quality (high-quality vs low-quality).

We pooled the adjusted ORs, RRs and 95%CIs based on both fixed-effects and random-effects models. Because the incidence of gastric cancer was low (< 5%), as evidenced in the cohort studies, we concluded that the outcome was sufficiently rare to assume that the OR could be used to approximate the RR. Heterogeneity was assessed using the Higgins I2 value, which measures the percentage of total variance across studies, which is attributable to heterogeneity rather than chance. Negative I2 values were set at zero to ensure that I2 fell between 0% (no observed heterogeneity) and 100% (maximal heterogeneity)[31,32]. We considered an I2 value greater than 50% to represent substantial heterogeneity. When the heterogeneity was substantial, we conducted sensitivity analyses: the changes in the I2 values were examined by removing each study from the analysis to determine which studies contributed most significantly to the heterogeneity. We assessed between-group heterogeneity using analysis of variance. When heterogeneity was found, we performed a meta-regression using the subgroup categories.

We used the Woolf method (inverse variance method) for a fixed-effects analysis[33,34], and we used the DerSimonian and Laird method for a random-effects analysis[35]. Begg’s funnel plot and Egger’s test were used to identify publication bias. Publication bias was detected in studies when the funnel plot was asymmetrical or the P-value was less than 0.05 using Egger’s test. We used the Stata/SE version 10.1 software program (StataCorp, College Station, TX, United States) for the statistical analysis.

RESULTS

Identification of relevant studies

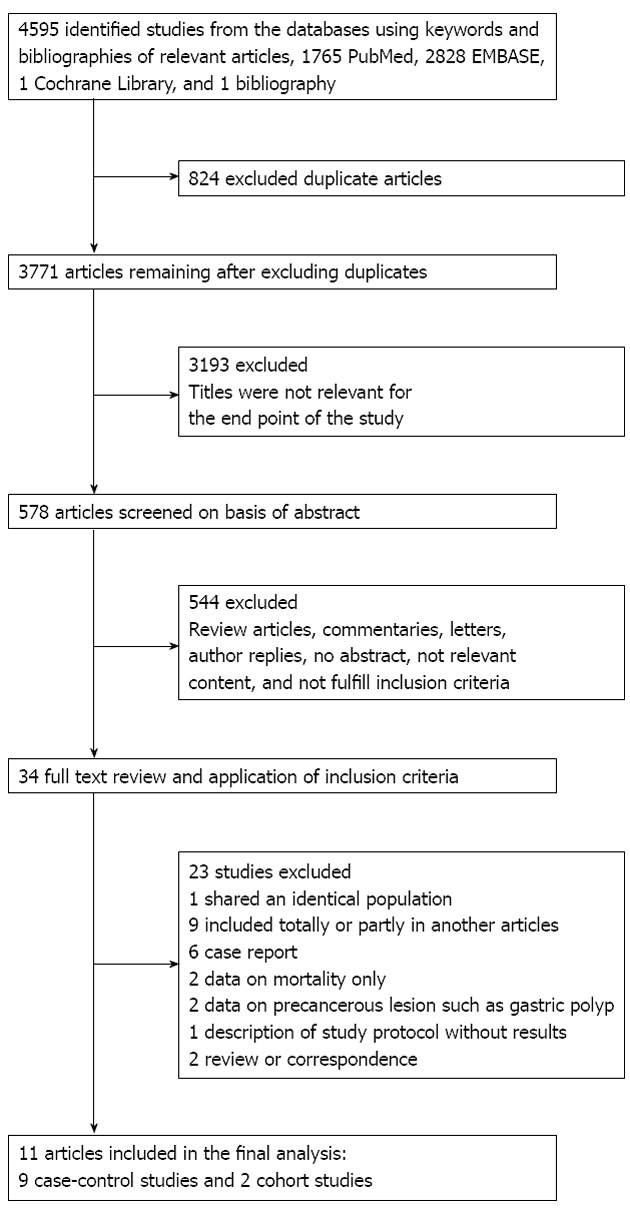

Figure 1 shows a flow diagram of the study selection. A total of 4595 articles were identified by searching the three databases and relevant bibliographies. We excluded 824 duplicate articles and 3737 articles that did not satisfy the selection criteria. After the full texts of the remaining 34 articles were reviewed, the following 23 articles were excluded: one article from a study that shared an identical population[36]; 6 articles that were case reports[5-10]; 2 articles that included data on precancerous lesions, such as gastric polyps[37,38]; one article that described a study protocol without results[39]; 2 articles that only included mortality data[40,41]; 2 articles that were reviews or correspondence[25,42]; and 9 articles that were included totally or partially in another article[43-51]. As a result, we included 11 observational studies (9 case-control studies and 2 cohort studies), which ultimately met our inclusion criteria.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for identification of relevant studies.

Characteristics of the studies included in the final analysis

Table 1 shows the main characteristics of the 11 reviewed studies. Five studies were published in the 1990s[23-27], and 6 studies were published in the 2000s[52-57]. The countries where the studies had been conducted were as follows: the United States (n = 5), the United Kingdom (n = 2), Denmark (n = 2), Canada (n = 1), and Italy (n = 1). We identified a total of 94558 participants, which included 5980 cases and 88578 controls from the following articles: 1 article on a medical record-based case-control study, 3 articles on nested case-control studies, 2 articles on population-based case-control studies, and 2 articles on prospective cohort studies. Seven studies evaluated the association between H2RA use and the risk of gastric cancer, and 4 studies assessed the association between the use of H2RAs or PPIs and the risk of gastric cancer. The mean value for the methodological quality of the 11 studies was 6.64 stars according to the NOS (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of observational studies on acid suppressive drugs and gastric cancer

| Ref. | Country | Design | Study period | Range of age (yr) | Population | Drugs | Adjusted OR or RR (95%CI) | Study quality1 | Adjustment for covariates |

| La Vecchiaet al[23] | Italy | CC | 1985-1989 | 27-74 | 563 cases and 1501 controls | Cimetidine, Ranitidine | 1.80 (1.20 -2.70) | 5 | Age, sex, education, smoking, alcohol, coffee |

| Johnson et al[24] | United States | CC | 1988-1992 | NA | 113 cases and 452 matched controls | Cimetidine, Ranitidine | 2.00 (1.00 -3.90) | 5 | Age, sex, first pharmacy use |

| Møller et al[25] | Denmark | PCC | 1977-1990 | NA | 134 cases among 16739 | Cimetidine | 2.30 (1.60-3.10) | 6 | Age, sex, diagnosis, method of diagnosis |

| Schumacher et al[26] | United States | CC | 1981-1987 | 17-94 | 99 cases and 365 controls | Cimetidine | 2.30 (0.80 -6.90) | 6 | Age, sex, date of first pharmacy use |

| Chow et al[27] | United States | MCC | 1986-1992 | NA | 196 cases and 200 controls | Cimetidine, Ranitidine, Famotidine, Nizatidine | 0.60 (0.30-1.30) | 6 | Race, smoking, BMI, number of composite conditions2 |

| Farrow et al[52] | United States | PBCC | 1993-1995 | 30-79 | 293 esophageal adenoca, 221 esophageal SCC, 261 gastric cardia adenoca, 368 non-cardia gastric adenoca and 695 controls | Cimetidine, Ranitidine, Famotidine, Nizatidine | 1.00 (0.60-1.90) | 7 | Age, sex, study center, smoking, BMI, history of gastric or duodenal ulcer, GERD symptom frequency, alcohol |

| Suleiman et al[53] | United Kingdom | NCC | 1990-1992 | NA | 231 cases among 9876 controls | Cimetidine, Ranitidine | 2.56 (0.17-38.09) | 7 | Age, sex, MI, antacid, steroid, smoking, alcohol, social class, height, weight |

| García Rodríguez et al[54] | United Kingdom | NCC | 1994-2001 | 40-84 | 287 esophageal adenoca, 195 gastric cardiac adenoca, 327 gastric non-cardia adenoca and 10000 controls | H2RAs, PPIs | 1.24 (0.88-1.75) | 8 | Age, sex, calendar year, smoking, alcohol, BMI, UGI disorder, hiatal hernia, GU, DU, dyspepsia |

| Tamim et al[55] | Canada | NCC | 1995-2003 | NA | 1589 cases and 12991 controls | H2RAs, PPIs | 1.37 (1.22-1.53) | 8 | Age, sex number of prescriptions to any drug, total length of hospitalizations and number of visit to GPs, specialist, emergency rooms |

| Duan et al[56] | United States | PBCC | 1992-1997 | NA | 220 esophageal adenoca, 277 gastric cardiac adenoca, 441 distal gastric adenoca and 1356 controls | H2RAs, PPIs | 1.15 (0.58 -2.29) | 7 | Age, sex, race, birthplace, education, smoking, BMI, history of UGI symptom |

| Poulsen et al[57] | Denmark | PCC | 1990-2003 | NA | 161 cases among users of 18790 PPIs or 17478 H2RAs | Omeprazole, Lanzoprazole, Esomeprazole, Pantoprazole, Rabeprazole, Cimetidine, Ranitidine, Nizatidine, Famotidine | 1.30 (0.70-2.30) | 8 | Age, sex, calendar period, history of H.pylori, gastroscopy year, COPD, alcohol, NSAID |

Study quality was judged based on the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (range, 1-9 stars). The mean value for the methodological quality of 11 studies was 6.64 stars;

Number of composite conditions were created to include gastroesophageal reflux, hiatal hernia, esophagitis/esophageal ulcer, or difficulty swallowing. OR: Odds ratio; RR: Relative risk; CC: Case-control; MCC: Medical record based case-control; PBCC: Population-based case-control study; NCC: Nested case-control study; PCC: Prospective cohort study; NA: Not available; Adenoca: Adenocarcinoma; SCC: Squamus cell carcinoma; H2RAs: Histamine 2-receptor antagonists; PPIs: Proton pump inhibitors; BMI: Body mass index; GERD: Gastroesophageal reflux disease; MI: Myocardial infarction; UGI: Upper gastrointestinal; GU: Gastric ulcer; DU: Duodenal ulcer; GPs: General practitioners; COPD: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; NSAID: Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

Overall use of acid suppressive drugs and the risk of gastric cancer

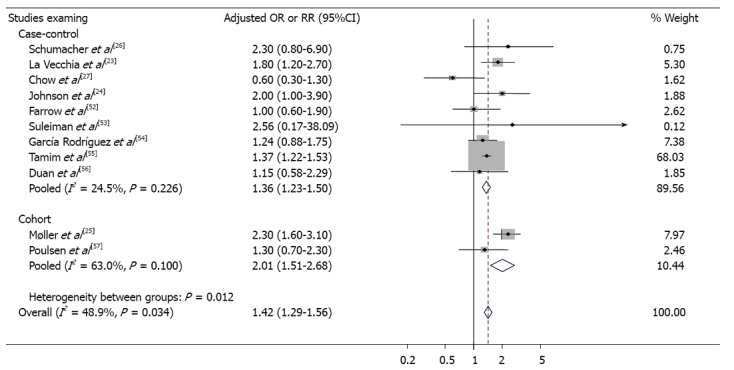

Figure 2 shows the association between the use of acid suppressive drugs and gastric cancer risk. The overall use of H2RAs and PPIs was associated with an increased risk of gastric cancer in 9 case-control studies [adjusted OR = 1.36; 95%CI: 1.23-1.50, n = 9, I2 = 24.5% (range, 0.0%-64.0%)] and in 2 cohort studies [adjusted RR, 2.01; 95%CI: 1.51-2.68, n = 2, I2 = 63.0% (not available)] using a fixed-effects model, and this association was observed in a combined study [adjusted OR and RR, 1.42; 95%CI: 1.29-1.56, n = 11, I2 = 48.9% (range, 0.0%-74.0%)]. As shown in Table 2, an increased risk of gastric cancer was found with H2RA use [adjusted OR = 1.40; [95%CI: 1.24-1.59, n = 10, I2 = 59.5% (range, 19.0%-80.0%)] and with PPI use [adjusted OR = 1.39; 95%CI: 1.19-1.64, n = 3, I2 = 0.0% (range, 0.0%-90.0%)]. In a sensitivity analysis, when the study by Møller et al[25] was removed, the I2 values of the H2RA studies decreased from 59.5% to 34.3%, but the effect remained significant. In addition, when stratified by the study design, H2RA use was positively associated with gastric cancer in both case-control [adjusted OR = 1.30; 95%CI: 1.13-1.49, n = 8, I2 = 42.0% (range, 0.0%-74.0%)] and cohort [adjusted RR, 1.84; 95%CI: 1.41-2.41, n = 2, I2 = 80.4% (not available)] studies. The use of PPIs was associated with an increased risk of gastric cancer in case-control studies [adjusted OR = 1.44; 95%CI: 1.21-1.71, n = 2, I2 = 23.5% (not available)], whereas only one cohort study was conducted to evaluate the use of PPIs (adjusted RR, 1.20; 95%CI: 0.80-1.80) (data were not shown).

Figure 2.

Meta-analysis results of individual and pooled adjusted odds ratio or relative risk of gastric cancer. The size of each square is proportional to the study’s weight. Diamonds are the summary estimate from the pooled studies with 95%CI. OR: Odds ratio; RR: Relative risk.

Table 2.

Association between acid suppressive drugs use and gastric cancer risk in subgroup meta-analysis

| Category | No. of studies | Adjusted OR/RR (95%CI) | Heterogeneity, I2 % (95%CI) | Model used | Heterogeneity between groups |

| Type of drugs | P = 0.01 | ||||

| H2RAs | 10[23-27,52-55,57] | 1.40 (1.24-1.59) | 59.5 (19.0-80.0)1 | Fixed-effects | |

| PPIs | 3[54,55,57] | 1.39 (1.19-1.64) | 0.0 (0.0-90.0) | Fixed-effects | |

| Location of gastric cancer | P = 0.03 | ||||

| GE junction | 2[24,26] | 2.28 (0.97-5.35) | 0.0 (NA) | Fixed-effects | |

| Gastric cardia | 4[52,54-56] | 0.88 (0.63-1.24) | 9.2 (0.0-86.0) | Fixed-effects | |

| Non-cardia | 6[24,26,52,54-56] | 1.42 (1.12-1.79) | 0.0 (0.0-75.0) | Fixed-effects | |

| Duration of drugs use | P = 0.27 | ||||

| Within 5 yr | 7[23,24,26,27,52,55,57] | 1.58 (1.35-1.81) | 60.2 (9.0-83.0)1 | Fixed-effects | |

| Over 5 yr | 6[23,24,26,27,52,57] | 1.24 (0.84-1.84) | 25.4 (0.0-69.0) | Fixed-effects | |

| Study quality | P = 0.01 | ||||

| High-quality2 | 6[52,53,54,55-57] | 1.34 (1.21-1.48) | 0.0 (0.0-75.0) | Fixed-effects | |

| Low-quality | 5[23-27] | 1.86 (1.49-2.32) | 63.5 (4.0-86.0)1 | Fixed-effects |

I2 value greater than 50% represents substantial heterogeneity. We conducted sensitivity analyses by removing each study to determine the studies that contributed most to the heterogeneity;

High quality study was considered a study awarded 7 or more stars, as standard criteria have not been established. OR: Odds ratio; RR: Relative risk; H2RAs: Histamine 2-receptor antagonists; PPIs: Proton pump inhibitors; GE junction: Gastroesophageal junction; NA: Not available.

Subgroup meta-analysis

In a subgroup meta-analysis, acid suppressive drugs were associated with an increased gastric cancer risk within 5 years of use [adjusted OR = 1.58; 95%CI: 1.35-1.81, n = 7, I2 = 60.2% (not available)]. In a sensitivity analysis, when the study by La Vecchia et al[23] was removed, the I2 values decreased from 60.2% to 41.4%; however, the summary estimate indicated an elevated risk of gastric cancer. Additionally, a positive association was observed in patients with more than 5 years of acid suppressive drug use. However, there was no statistical significance [adjusted OR = 1.24; 95%CI: 0.84-1.84, n = 6, I2 = 25.4% (not available)] (Table 2). The between-group differences in the effect estimates for within 5 years of exposure vs more than 5 years of exposure were not significant (P = 0.27).

Regarding the location of gastric cancer, a significant positive association was observed between the use of acid suppressive drugs and non-cardia cancer risk [adjusted OR = 1.42; 95%CI: 1.12-1.79, n = 6, I2 = 0.0% (not available)], whereas a marginal significance was observed in gastroesophageal junction cancer and the use of acid suppressive drugs [adjusted OR = 2.28; 95%CI: 0.97-5.35, n = 2, I2 = 0.0% (not available)]. However, there was no significant association between the use of acid suppressive drugs and gastric cardia cancer [adjusted OR = 0.88; 95%CI: 0.63-1.24, n = 4, I2 = 9.2% (0.0%-86.0%)]. The between-group differences in the effect estimates for non-cardia cancer vs gastroesophageal junction cancer vs gastric cardia cancer were significant (P = 0.03). The meta-regression according to the site of cancer indicated that the effect estimates for non-cardia cancers were significantly higher than those for cardia cancers (P = 0.02), and the effect estimates for gastroesophageal junction cancers were significantly different from those of cardia cancers (P = 0.04).

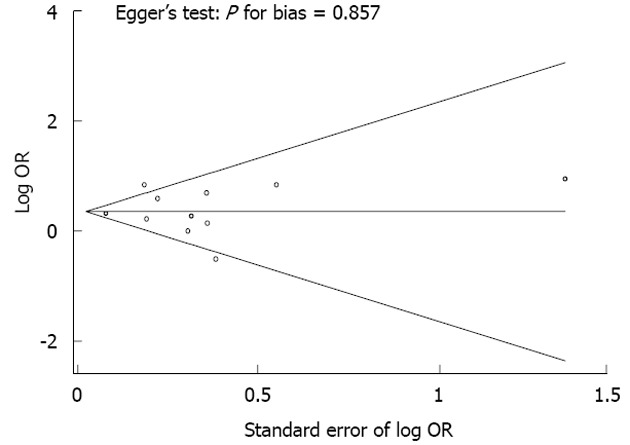

There was an increased risk of gastric cancer that was associated with the use of acid suppressive drugs in both high-quality [adjusted OR = 1.34; 95%CI: 1.21-1.48, n = 6, I2 = 0.0% (range, 0.0%-75.0%)] and low-quality [adjusted OR = 1.86; 95%CI: 1.49-2.32, n = 5, I2 = 63.5% (range, 4.0%-86.0%)] studies. No publication bias was observed in the selected studies (Figure 3, Begg’s funnel plot was symmetrical; Egger’s test, P for bias = 0.857).

Figure 3.

Begg’s funnel plots and Egger’s test for identifying publication bias (P = 0.857) in a meta-analysis of observational studies (n = 11). OR: Odds ratio.

DISCUSSION

In this meta-analysis of 11 observational studies, we found that both H2-receptor antagonist use and proton pump inhibitor use were associated with an increased risk of gastric cancer. In site-specific analyses, an increased risk of non-cardia gastric cancer was observed in patients who used acid suppressive drugs, whereas acid suppressive drug use was not associated with the risk of gastric cardia cancer.

Our meta-analysis has several strengths. This systemic review was the most comprehensive meta-analysis to date of observational studies that addressed the association between the use of acid suppressive drugs and the risk of gastric cancer, which included a large number of studies and participants. We performed a detailed analysis by stratifying the type of drugs (H2RAs or PPIs), the location of gastric cancer (gastroesophageal junction, cardia, or non-cardia), the duration of acid suppressive drug use, and the study quality.

Previous studies suggested that long-term H2RA use may increase gastric cancer[11-13], and long-term PPI treatment induced gastric fundic polyps, which led to the development of precancerous lesions[5-8]. There is biological evidence of the effect of acid suppressive drug use on the risk of gastric cancer. First, PPIs and H2RAs can reduce gastric acidity by modulating H(+)-K(+)-ATPase or competitive inhibitors of histamine binding sites in gastric parietal cells. Decreased gastric acidity, whether caused by gastric atrophy or acid suppressive drug-induced hypochlorhydria, may result in increased bacterial colonization and a greater number of bacteria that can produce nitrosamines[16,58], which are compounds that are associated with an increased risk of gastric adenocarcinoma[59]. Second, the reduction of gastric acid secretion by acid-suppressive drugs switches on the positive feedback of a gastric acid-producing cascade, which leads to hypergastrinemia[19]. This condition is a possible cause of carcinoids, gastric polyps, and gastric and colonic carcinomas because elevated serum gastrin could have a trophic effect on neoplastic growth in the gastrointestinal tract[60]. The use of long-term PPIs can cause hyperplasia in enterochromaffin-like cells and increase the incidence of atrophic gastritis and gastric polyps, which are a precursor to gastric cancer[37,38,43-46].

We found that acid suppressive drugs increased the risk of non-cardia gastric cancer, whereas acid suppressive drug use was not associated with a risk of gastric cardia cancer. One possible mechanism may be associated with the augmented effects of acid suppressive drugs and other risk factors of non-cardia gastric cancer, such as gastric atrophy and Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection[61,62]. Several authors suggested that omeprazole treatment was associated with an elevated incidence of gastric corpus mucosal atrophy[63], and long-term PPI treatment in H. pylori infected patients could accelerate the development of corpus atrophic gastritis[64,65]. In addition, recent studies suggested that a history of H. pylori eradication prior to long-term PPI therapy could prevent the development of atrophic gastritis[57,66,67]. Considering this knowledge, further studies are needed to clarify the association between acid suppressive drug use and the risk of non-cardia gastric cancer, especially for patients with gastric atrophy and H. pylori infection.

We found that within 5 years of use, acid suppressive drugs increased the risk of gastric cancer, whereas there was a non-significant increased risk of gastric cancer among users of acid suppressive drugs for more than 5 years. Our meta-analysis was underpowered to detect statistically significant differences between the studies according to the duration of exposure; however, the qualitative differences were noteworthy. Early gastric symptoms of stomach cancer are typically similar to those of benign conditions, such as peptic ulcers, GERD, or functional gastrointestinal disease[23], which could lead to the use of acid suppressive drugs. Therefore, we could not exclude the possibility of misspecification and the protopathic bias of gastric cancer, especially among 5-year acid suppressive drug users. We found that two of the earliest studies (Møller et al[25] and La Vecchia et al[23]) contributed most significantly to the heterogeneity in the studies of H2RAs and in the studies that examined exposure within 5 years of the incidence of cancer. These studies may have been influenced by misspecification because endoscopic tools that would have detected early stage cancer were not readily available when the studies were conducted. There could be bias due to existing gastric conditions; however, we recommend that future studies carefully consider the appropriate control of previous gastric conditions.

Our meta-analysis has several limitations. First, most of the studies in our meta-analysis were observational studies. Observational studies, even when well-controlled, are susceptible to various biases, which may reduce the quality of the analysis. Second, most of the studies in our meta-analysis came from Western countries. The occurrence of gastric cancer is rapidly increasing in the United States and in Western Europe[68]; however, this disease is a more significant public health problem in Asia. Third, we did not have access to individual data on dose-response relationships that may have affected gastric acid production. Finally, we could not evaluate the effect of underlying gastric conditions, e.g., H. pylori infection, because these data were not presented in each study.

Our meta-analysis demonstrated that the use of acid suppressive drugs was associated with an increased risk of gastric cancer. Our findings should be confirmed by more prospective cohort studies that are designed with larger sample sizes and longer follow-up durations to test the effect of acid suppressive drugs on the risk of gastric cancer. These studies should focus on previous underlying gastric conditions for which acid suppressive drugs are prescribed and the dose response of acid suppressive drugs use.

COMMENTS

Background

The widespread use of acid suppressive drugs has led to concern about the development of adverse effects owing to prolonged gastric acid suppression, particularly the development of gastric polyps or gastric neoplasms. Authors performed a meta-analysis of cohort studies and case-control studies to determine whether the use of acid suppressive drugs, such as histamine 2-receptor antagonists (H2RAs) and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), can increase the risk for gastric cancer.

Research frontiers

Several case reports suggested that antacids may increase the risk of gastric polyps or cancer. Several epidemiological studies have evaluated the association between long-term gastric acid suppression and the risk of gastrointestinal neoplasms. However, epidemiological studies have reported inconsistent findings regarding the association between the use of acid suppressive drugs and gastric cancer risk. To date, no systematic meta-analysis has been published on the use of acid suppressive drugs and the risk of gastric cancer.

Innovations and breakthroughs

In this meta-analysis of case-control and cohort studies, the authors found that both H2RA and PPI use were associated with an increased risk of gastric cancer. In site-specific analyses, an increased risk of non-cardia gastric cancer was observed in patients who used acid suppressive drugs, whereas acid suppressive drug use was not associated with a risk of gastric cardia cancer.

Applications

The use of acid suppressive drugs is associated with an increased risk of gastric cancer. However, authors could not exclude the possibility of misspecification and the protopathic bias of gastric cancer. The early gastric symptoms of stomach cancer are typically similar to those of benign conditions, such as peptic ulcers, gastroesophageal reflux disease, or functional gastrointestinal disease, which could lead to the use of acid suppressive drugs. There could be bias due to existing gastric conditions; therefore, they recommend that future studies carefully consider the appropriate control of previous gastric conditions.

Terminology

Acid suppressive drugs can reduce gastric acidity by modulating H(+)-K(+)-ATPase or competitive inhibitors of histamine binding sites in gastric parietal cells, which leads to hypergastrinemia. This condition is a possible cause of carcinoids, gastric polyps, and gastric and colonic carcinomas because elevated serum gastrin could have a trophic effect on neoplastic growth in the gastrointestinal tract.

Peer review

This study may lead conclusion that acid suppressive drugs such as H2R blocker or PPI may act as a stimulator for gastric cancer. It is difficult to obtain a substantial conclusion from 11 studies adopted by this paper because all 11 papers were observational study and no information on Helicobacter pylori infection. This paper is good for publication.

Footnotes

Supported by A National Research Foundation of Korea Grant funded by the Korean Government, No. 2010-0004429

P- Reviewer Nagahara H S- Editor Wen LL L- Editor A E- Editor Xiong L

References

- 1.Jacobson BC, Ferris TG, Shea TL, Mahlis EM, Lee TH, Wang TC. Who is using chronic acid suppression therapy and why? Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:51–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolfe MM, Sachs G. Acid suppression: optimizing therapy for gastroduodenal ulcer healing, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and stress-related erosive syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:S9–31. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(00)70004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marks RD, Richter JE, Rizzo J, Koehler RE, Spenney JG, Mills TP, Champion G. Omeprazole versus H2-receptor antagonists in treating patients with peptic stricture and esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 1994;106:907–915. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90749-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vigneri S, Termini R, Leandro G, Badalamenti S, Pantalena M, Savarino V, Di Mario F, Battaglia G, Mela GS, Pilotto A. A comparison of five maintenance therapies for reflux esophagitis. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1106–1110. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199510263331703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim JS, Chae HS, Kim HK, Cho YS, Park YW, Son HS, Han SW, Choi KY. [Spontaneous resolution of multiple fundic gland polyps after cessation of treatment with omeprazole] Korean J Gastroenterol. 2008;51:305–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamamoto T, Matsumoto J, Kosaihira T, Nomoto M, Kitajima S, Arima T. [A case of gastric fundic polyps during long-term treatment of reflux esophagitis with omeprazole] Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2003;100:421–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kazantsev GB, Schwesinger WH, Heim-Hall J. Spontaneous resolution of multiple fundic gland polyps after cessation of treatment with lansoprazole and Nissen fundoplication: a case report. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:600–602. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.122583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Vlierberghe H, De Vos M, De Cock G, Cuvelier C, Elewaut A. Fundic gland polyps: three other case reports suggesting a possible association with acid suppressing therapy. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 1997;60:240–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stolte M, Bethke B, Seifert E, Armbrecht U, Lütke A, Goldbrunner P, Rabast U. Observation of gastric glandular cysts in the corpus mucosa of the stomach under omeprazole treatment. Z Gastroenterol. 1995;33:146–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.el-Zimaity HM, Jackson FW, Graham DY. Fundic gland polyps developing during omeprazole therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:1858–1860. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hawker PC, Muscroft TJ, Keighley MR. Gastric cancer after cimetidine in patient with two negative pre-treatment biopsies. Lancet. 1980;1:709–710. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mullen PW. Gastric cancer in patients who have taken cimetidine. Lancet. 1979;1:1406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taylor TV, Lee D, Howatson AG, Anderson J, MacLeod IB. Gastric cancer in patients who have taken cimetidine. Lancet. 1979;1:1135–1136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Langman MJ. Antisecretory drugs and gastric cancer. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1985;290:1850–1852. doi: 10.1136/bmj.290.6485.1850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Freston JW. Cimetidine: II. Adverse reactions and patterns of use. Ann Intern Med. 1982;97:728–734. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-97-5-728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stockbruegger RW. Bacterial overgrowth as a consequence of reduced gastric acidity. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1985;111:7–16. doi: 10.3109/00365528509093749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klinkenberg-Knol EC, Festen HP, Jansen JB, Lamers CB, Nelis F, Snel P, Lückers A, Dekkers CP, Havu N, Meuwissen SG. Long-term treatment with omeprazole for refractory reflux esophagitis: efficacy and safety. Ann Intern Med. 1994;121:161–167. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-121-3-199408010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lamberts R, Creutzfeldt W, Stöckmann F, Jacubaschke U, Maas S, Brunner G. Long-term omeprazole treatment in man: effects on gastric endocrine cell populations. Digestion. 1988;39:126–135. doi: 10.1159/000199615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laine L, Ahnen D, McClain C, Solcia E, Walsh JH. Review article: potential gastrointestinal effects of long-term acid suppression with proton pump inhibitors. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:651–668. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2000.00768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Havu N. Enterochromaffin-like cell carcinoids of gastric mucosa in rats after life-long inhibition of gastric secretion. Digestion. 1986;35 Suppl 1:42–55. doi: 10.1159/000199381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith JP, Wood JG, Solomon TE. Elevated gastrin levels in patients with colon cancer or adenomatous polyps. Dig Dis Sci. 1989;34:171–174. doi: 10.1007/BF01536047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seitz JF, Giovannini M, Gouvernet J, Gauthier AP. Elevated serum gastrin levels in patients with colorectal neoplasia. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1991;13:541–545. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199110000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.La Vecchia C, Negri E, Franceschi S, D’Avanzo B. Histamine-2-receptor antagonists and gastric cancer: update and note on latency and covariates. Nutrition. 1992;8:177–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson AG, Jick SS, Perera DR, Jick H. Histamine-2 receptor antagonists and gastric cancer. Epidemiology. 1996;7:434–436. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199607000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Møller H, Nissen A, Mosbech J. Use of cimetidine and other peptic ulcer drugs in Denmark 1977-1990 with analysis of the risk of gastric cancer among cimetidine users. Gut. 1992;33:1166–1169. doi: 10.1136/gut.33.9.1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schumacher MC, Jick SS, Jick H, Feld AD. Cimetidine use and gastric cancer. Epidemiology. 1990;1:251–254. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199005000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chow WH, Finkle WD, McLaughlin JK, Frankl H, Ziel HK, Fraumeni JF. The relation of gastroesophageal reflux disease and its treatment to adenocarcinomas of the esophagus and gastric cardia. JAMA. 1995;274:474–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beresford J, Colin-Jones DG, Flind AC, Langman MJ, Lawson DH, Logan RF, Paterson KR, Vessey MP. Postmarketing surveillance of the safety of cimetidine: 15-year mortality report. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 1998;7:319–322. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1557(199809/10)7:5<319::AID-PDS367>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, Moher D, Becker BJ, Sipe TA, Thacker SB. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283:2008–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Available from: http: //www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.htm.

- 31.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mantel N, Haenszel W. Statistical aspects of the analysis of data from retrospective studies of disease. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1959;22:719–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Woolf B. On estimating the relation between blood group and disease. Ann Hum Genet. 1955;19:251–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.1955.tb01348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Møller H, Lindvig K, Klefter R, Mosbech J, Møller Jensen O. Cancer occurrence in a cohort of patients treated with cimetidine. Gut. 1989;30:1558–1562. doi: 10.1136/gut.30.11.1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Singh P, Indaram A, Greenberg R, Visvalingam V, Bank S. Long term omeprazole therapy for reflux esophagitis: follow-up in serum gastrin levels,EC cell hyperplasia and neoplasia. World J Gastroenterol. 2000;6:789–792. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v6.i6.789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jalving M, Koornstra JJ, Wesseling J, Boezen HM, DE Jong S, Kleibeuker JH. Increased risk of fundic gland polyps during long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:1341–1348. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eslami L, Kalantarian S, Nasseri-Moghaddam S, Majdzadeh R. Long term proton pump inhibitor (PPI) use and incidence of gastric (pre) malignant lesions. New York: John Wiley and Sons, Ltd; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bateman DN, Colin-Jones D, Hartz S, Langman M, Logan RF, Mant J, Murphy M, Paterson KR, Rowsell R, Thomas S, et al. Mortality study of 18 000 patients treated with omeprazole. Gut. 2003;52:942–946. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.7.942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Colin-Jones DG, Langman MJ, Lawson DH, Logan RF, Paterson KR, Vessey MP. Postmarketing surveillance of the safety of cimetidine: 10 year mortality report. Gut. 1992;33:1280–1284. doi: 10.1136/gut.33.9.1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.La Vecchia C, Tavani A. A review of epidemiological studies on cancer in relation to the use of anti-ulcer drugs. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2002;11:117–123. doi: 10.1097/00008469-200204000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Solcia E, Fiocca R, Havu N, Dalväg A, Carlsson R. Gastric endocrine cells and gastritis in patients receiving long-term omeprazole treatment. Digestion. 1992;51 Suppl 1:82–92. doi: 10.1159/000200921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pashankar DS, Israel DM. Gastric polyps and nodules in children receiving long-term omeprazole therapy. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2002;35:658–662. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200211000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cats A, Schenk BE, Bloemena E, Roosedaal R, Lindeman J, Biemond I, Klinkenberg-Knol EC, Meuwissen SG, Kuipers EJ. Parietal cell protrusions and fundic gland cysts during omeprazole maintenance treatment. Hum Pathol. 2000;31:684–690. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2000.7637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Grieken NC, Meijer GA, Weiss MM, Bloemena E, Lindeman J, Baak JP, Meuwissen SG, Kuipers EJ. Quantitative assessment of gastric corpus atrophy in subjects using omeprazole: a randomized follow-up study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2882–2886. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.04242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Genta RM, Rindi G, Fiocca R, Magner DJ, D’Amico D, Levine DS. Effects of 6-12 months of esomeprazole treatment on the gastric mucosa. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1257–1265. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Freeman HJ. Proton pump inhibitors and an emerging epidemic of gastric fundic gland polyposis. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:1318–1320. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rindi G, Fiocca R, Morocutti A, Jacobs A, Miller N, Thjodleifsson B. Effects of 5 years of treatment with rabeprazole or omeprazole on the gastric mucosa. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;17:559–566. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200505000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lamberts R, Brunner G, Solcia E. Effects of very long (up to 10 years) proton pump blockade on human gastric mucosa. Digestion. 2001;64:205–213. doi: 10.1159/000048863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Geboes K, Dekker W, Mulder CJ, Nusteling K. Long-term lansoprazole treatment for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: clinical efficacy and influence on gastric mucosa. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:1819–1826. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.01105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Farrow DC, Vaughan TL, Sweeney C, Gammon MD, Chow WH, Risch HA, Stanford JL, Hansten PD, Mayne ST, Schoenberg JB, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux disease, use of H2 receptor antagonists, and risk of esophageal and gastric cancer. Cancer Causes Control. 2000;11:231–238. doi: 10.1023/a:1008913828105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Suleiman UL, Harrison M, Britton A, McPherson K, Bates T. H2-receptor antagonists may increase the risk of cardio-oesophageal adenocarcinoma: a case-control study. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2000;9:185–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.García Rodríguez LA, Lagergren J, Lindblad M. Gastric acid suppression and risk of oesophageal and gastric adenocarcinoma: a nested case control study in the UK. Gut. 2006;55:1538–1544. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.086579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tamim H, Duranceau A, Chen LQ, Lelorier J. Association between use of acid-suppressive drugs and risk of gastric cancer. A nested case-control study. Drug Saf. 2008;31:675–684. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200831080-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Duan L, Wu AH, Sullivan-Halley J, Bernstein L. Antacid drug use and risk of esophageal and gastric adenocarcinomas in Los Angeles County. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:526–533. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Poulsen AH, Christensen S, McLaughlin JK, Thomsen RW, Sørensen HT, Olsen JH, Friis S. Proton pump inhibitors and risk of gastric cancer: a population-based cohort study. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:1503–1507. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stockbrugger RW, Cotton PB, Eugenides N, Bartholomew BA, Hill MJ, Walters CL. Intragastric nitrites, nitrosamines, and bacterial overgrowth during cimetidine treatment. Gut. 1982;23:1048–1054. doi: 10.1136/gut.23.12.1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rowland JR. The toxicology of N-nitroso compounds, In Hill MJ, editors. Nitrosamines-Toxicology and Microbiology. London: Ellis Horwood; 1988. pp. 117–141. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Solomon TE. Trophic effects of pentagastrin on gastrointestinal tract in fed and fasted rats. Gastroenterology. 1986;91:108–116. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(86)90446-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Correa P. A human model of gastric carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 1988;48:3554–3560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Helicobacter and Cancer Collaborative Group. Gastric cancer and Helicobacter pylori: a combined analysis of 12 case control studies nested within prospective cohorts. Gut. 2001;49:347–353. doi: 10.1136/gut.49.3.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Klinkenberg-Knol EC, Nelis F, Dent J, Snel P, Mitchell B, Prichard P, Lloyd D, Havu N, Frame MH, Romàn J, et al. Long-term omeprazole treatment in resistant gastroesophageal reflux disease: efficacy, safety, and influence on gastric mucosa. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:661–669. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(00)70135-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kuipers EJ, Lundell L, Klinkenberg-Knol EC, Havu N, Festen HP, Liedman B, Lamers CB, Jansen JB, Dalenback J, Snel P, et al. Atrophic gastritis and Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with reflux esophagitis treated with omeprazole or fundoplication. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1018–1022. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199604183341603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Eissele R, Brunner G, Simon B, Solcia E, Arnold R. Gastric mucosa during treatment with lansoprazole: Helicobacter pylori is a risk factor for argyrophil cell hyperplasia. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:707–717. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v112.pm9041231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Moayyedi P, Wason C, Peacock R, Walan A, Bardhan K, Axon AT, Dixon MF. Changing patterns of Helicobacter pylori gastritis in long-standing acid suppression. Helicobacter. 2000;5:206–214. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5378.2000.00032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schenk BE, Kuipers EJ, Nelis GF, Bloemena E, Thijs JC, Snel P, Luckers AE, Klinkenberg-Knol EC, Festen HP, Viergever PP, et al. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on chronic gastritis during omeprazole therapy. Gut. 2000;46:615–621. doi: 10.1136/gut.46.5.615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Devesa SS, Blot WJ, Fraumeni JF. Changing patterns in the incidence of esophageal and gastric carcinoma in the United States. Cancer. 1998;83:2049–2053. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]