Abstract

Objectives

To establish the attitudes of glaucoma specialists to the frequency of visual field (VF) testing in the UK, using the NICE recommendations as a standard for ideal practice.

Design

Interview and postal survey.

Setting

UK and Eire Glaucoma Society national meeting 2011 in Manchester, UK, with a second round of surveys administered by post.

Participants

All consultant glaucoma specialists in England and Wales were invited to complete the survey.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

(1) Compliance of assigned follow-up VF intervals with NICE guidelines for three hypothetical patient scenarios, with satisfactory treated intraocular pressure and (a) no evidence of VF progression; (b) evidence of VF progression and (c) uncertainty about VF progression, and respondents were asked to provide typical follow-up intervals representative of their practice; (2) attitudes to research recommendations for six VF in the first 2 years for newly diagnosed patients with glaucoma.

Results

70 glaucoma specialists completed the survey. For each of the clinical scenarios a, b and c, 14 (20%), 33 (47%) and 28 (40%) responses, respectively, fell outside the follow-up interval recommended by NICE. Nearly half of the specialists (46%) agreed that 6 VF tests in the first 2 years was ideal practice, while 16 (28%) said this was practice ‘not possible’, with many giving resources within the NHS setting as a limiting factor.

Conclusions

The results from this survey suggest that there is a large variation in attitudes to follow-up intervals for patients with glaucoma in the UK, with assigned intervals for VF testing which are, in many cases, inconsistent with the guidelines from NICE.

Keywords: NICE recommendations, Survey, Primary open angle glaucoma, Visual fields

Article summary.

Article focus

There are approximately one million glaucoma-related outpatient visits in the National Health Service annually.

Visual field (VF) testing is one of the most frequent investigations performed for monitoring patients with glaucoma and requires substantial and specialist resource utilisation.

A survey was conducted to establish attitudes to the frequency of VF testing in the UK with reference to guidelines from the National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) and research recommendations.

Key messages

VF monitoring intervals assigned by clinicians (for hypothetical patient scenarios) are very variable and often outside intervals recommended by NICE.

Many specialists regard the research-recommended routine performance of six VF examinations in the first 2 years as impractical in the current health setting.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This is the first survey to establish the views of glaucoma subspecialists to the VF monitoring intervals for patients with glaucoma.

The surveyed population accounted for approximately half of the specialists nationally and the assumption has been made that this sample is representative of UK practice.

Introduction

Visual field (VF) testing, in the form of standard automated perimetry, is the most frequently performed investigation for the functional assessment of patients with primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) in the UK.1 The aim of VF testing is to detect functional deficit in patients with suspected disease and monitoring of patients with established POAG.2

The frequency of VF tests over a given period for a patient with POAG is governed by the clinician's estimate of the likelihood and speed of progression of disease, which in turn may depend on the level of intraocular pressure (IOP) control and stage of disease as well as other factors such as the age of the patient and degree of VF reliability. Test intervals are essentially a risk/benefit trade-off: an interval which is too long may allow timely detection of progressive VF loss to be missed while multiple tests at short-test intervals in patients at low risk of progression may mean unnecessary extra visits and use of hospital resource. Although some published guidelines regarding the frequency of VF testing are available, these vary considerably.3 4 Results from statistical modelling suggest that six VF tests in 2 years (ie, approximately 1 every 4 months) in newly diagnosed patients may be necessary to allow detection of patients who may be progressing ‘rapidly’ in terms of VF loss.5 The National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) has recognised the current lack of evidence regarding the frequency of monitoring intervals for patients with POAG and recommended future research in this area of study to substantiate current practice.3 Indeed, recent research has focused on the optimum number and interval between VF tests for patients.6

Given that POAG accounts for a major proportion of ophthalmology workload, with an estimated one million outpatient visits in the UK annually,3 the frequency of testing has important implications for resource management and service delivery, as well as cost in the outpatient setting.

We undertook a national survey to establish the attitudes of glaucoma subspecialists to the frequency of VF testing, using NICE recommendations as a benchmark, and also sought to investigate perceived barriers to frequent VF testing of patients with glaucoma.

Materials and methods

The current study was undertaken as part of a larger National Institute for Health Research (NIHR)-funded project to evaluate factors governing VF test intervals in clinical practice. The current study was needed in order to infer the extent to which actual VF intervals and frequency (investigated in a national audit of practice) may be influenced by the attitude of clinicians.

Survey population

The questionnaire was administered to all UK glaucoma consultants by two methods to ensure maximum response: (1) by hand at the UK & Eire Glaucoma Society (UKEGS) Meeting in December 2011 in Manchester or (2) by post, with a self-addressed prepaid envelope, in February 2012. All responses were carried out by self-completion of the questionnaire and were collected anonymously and then combined to form one dataset. All glaucoma specialists, identified from a list provided by the Royal College of Ophthalmologists (n=150), were sent the postal survey. Specialists who had previously completed the survey at UKEGS were requested not to respond again. This study was reviewed and approved by the City University London School of Health Science Research and Ethics committee.

Questionnaire design

The questionnaire consisted of five questions. Questions 1–3 were used to gather information of the grade and location of work (England and Wales) of the responders and to identify consultants with a subspecialist interest in glaucoma. Question 4 described three distinct situations designed to simulate common clinical scenarios. For patients with POAG who were being monitored on treatment and attending a follow-up assessment, responders were asked to assign typical follow-up assessment intervals for a patient with IOP deemed to be at (or below) ‘target IOP’ and

No evidence of VF progression and no change in treatment

Evidence of VF progression and change of treatment

Uncertainty about VF progression and no change of treatment

These scenarios were chosen to reflect the clinical situations which have been given by NICE.3 Follow-up intervals of 6–12 months for the first scenario and 2–6 months for the latter two have been recommended by NICE.

The last question, question 5, was open ended; specialists were asked their views about research that has suggested that all newly diagnosed patients would benefit from six VF examinations (every 4 months) in the first 2 years of follow-up from diagnosis in order to identify rapidly progressing patients.5

Data analysis

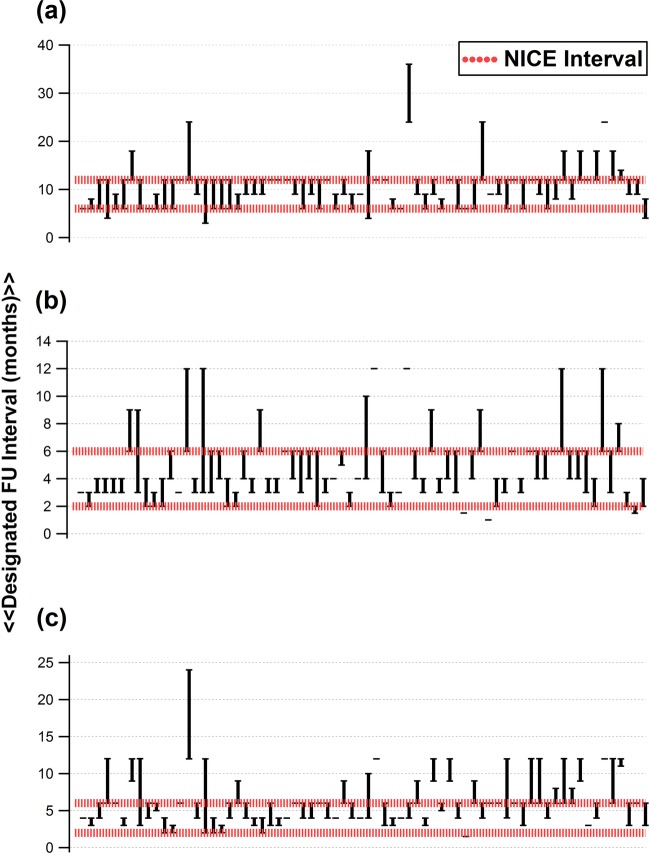

For each of the patient scenarios in question 4, the follow-up interval given by each responder was compared with NICE-recommended intervals. The proportion of responses (with either the minimum or maximum interval) lying outside NICE-recommended intervals was computed (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Responses from 70 Consultant Ophthalmologists with a declared subspecialist interest in glaucoma, giving minimum (lower error bars) and maximum (upper error bars) follow-up intervals for a hypothetical patient with intraocular pressure at ‘target’ and (A) no evidence of visual field progression and no change in treatment; (B) evidence of visual field progression and no change in treatment; (C) uncertainty about visual field progression and no change in treatment. Single bars represent values for which only a single interval was given by respondents, without specifying the minimum / maximum monitoring interval.

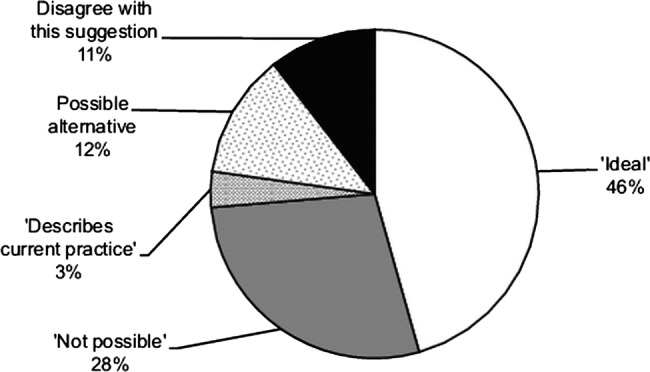

For question 5 (whether 6 VFs should be performed in the first 2 years for newly diagnosed patients), responses were classified into five categories for ease of reporting: ‘agree’; ‘diasgree’, already represents ‘current practice’ locally; ‘not possible’ and possible ‘alternatives’ to this practice and are represented in a pie chart (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Summary of views of responders to the suggestion that six visual field tests should be performed in the first 2 years for a newly diagnosed patient with primary open-angle glaucoma.

Results

The questionnaire was returned by 70 Consultant Ophthalmologists currently employed in England and Wales and with a self-declared specialist interest in glaucoma. From the conference, responses were obtained from 28 specialists. The remainder of the responses (42) were received through the postal survey. Figure 1 shows the follow-up intervals given by each of the responders for each of the clinical scenarios a, b and c described in question 4. For each of these, 14 (20%), 33 (47%) and 28 (40%) responses, respectively, fell outside the follow-up interval recommended by NICE. (The width of the 95% CI associated with these estimates, with n=70, is about ±12%.)

Question 5 was answered by 57 of the 70 specialists. Nearly half of these (26/57=46%) agreed that six VF tests in the first 2 years was ideal practice (figure 2), but admitted that the practicalities of this would be challenging. Example responses that fell in this category included, “Agree but practical issues found in a busy glaucoma clinic may be a hurdle to achieve this target.”

Two delegates (3%) indicated that this was already their current practice. Six specialists (11%) disagreed with the suggestion of six VF tests, while 16 (28%) said this was ‘not possible’, again listing limited ‘capacity’ or resources as a constraining factor. (The width of the 95% CI associated with these estimates, with n=57, is about ±15%.) Examples of responses that fell in the latter category included, “Totally out of touch with what is possible in the current NHS clinics with such limited capacity.” A few alternatives were suggested to the six VF tests, including alternating imaging and VF tests for detecting progression. For example, one responder stated, “Instead of function tests, structural ones: GDx (scanning laser polarimetry)/OCT would be better.”

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to report the attitudes of glaucoma consultant subspecialists in England and Wales to the frequency of VF testing for patients with glaucoma, by exploring the designated test intervals for patients in three clinical scenarios. The hypothesis was that clinicians would be fully compliant with NICE guidelines in their attitudes to intervals for VF testing. However, the results of the survey disprove this hypothesis. We found a wide variation in the designated test intervals, with respect to NICE recommendations. This variation in attitudes is likely to reflect differences in clinical practice, although this has yet to be established. A recent retrospective study of 100 patients conducted at a single centre found that 89% of assigned monitoring intervals were in accordance with NICE guidelines.7

The variation in individual attitudes to the frequency of testing is reflected in differing recommendations for the frequency of testing in glaucoma. For example, NICE recommend VF testing at 6–12 month intervals for a patient at target IOP and a stable VF.3 The European Glaucoma Society (EGS) recommends three VF tests in the first 2 years for a newly diagnosed patient with glaucoma, with less specific guidance thereafter.4

Given that more frequent testing is associated with a higher likelihood of identifying progression, variations in practice with regard to the frequency of testing are likely to imply inconsistencies in patient management and resource utilisation nationally. The authors estimate the cost of a single VF in an NHS setting to be in excess of 50 pounds per test.8 There are approximately 10 000 new cases of POAG per year. With these estimated costs, three tests per year equate to a cost of 1.5 million pounds per year for this newly diagnosed patient cohort alone. Clearly, the outpatient workload for patients with glaucoma has substantial cost implications for the NHS.

In view of the implications of frequent testing, it is unsurprising that research has focused on the frequency and intervals of VF tests.5 6 9–12 One suggested approach is to vary the inter-test interval based on the outcome of previous tests.11 12 Most of this research has recommended increasing the frequency of VF testing to ensure better sensitivity in diagnosing progression, without perhaps considering the cost/benefit ratio, or problems with false-positive detection in the presence of increased testing. One recent study proposed multiple tests at the start and end of a fixed ‘observation’ period, for more reliable identification of progressing patients.6

It is interesting that three VF tests annually, the number which may be required to detect ‘rapidly’ progressing patients and is consistent with the number recommended by NICE for patients with suboptimal IOP and evidence of progression, was seen as impractical by many UK ophthalmologists with a specialist interest in glaucoma in terms of availability of hospital resources. It would seem that the potential utility of UK ophthalmology departments to perform the number of VFs to meet clinical guidelines needs further investigation. While outsourcing visits to a community setting may lighten the hospital burden, this may have overall adverse cost implications.13 A further discussion of issues about service delivery for glaucoma management is beyond the scope of this report. One possible approach to increasing diagnostic power to detect progression in the face of a limited number of VF tests is to use alternative technology, in addition to VF testing for monitoring, such as optic nerve head imaging. Several methods have recently been suggested for integrating structural and functional tests for glaucoma progression,14–16 and the use of an additional diagnostic modality leads to greater accuracy for detecting progression than VF tests alone.15 It remains to be seen if these research ideas can translate to clinical practice.

A limitation of this and all studies of this nature is the response rate. An assumption has been made that responses from the surveyed consultants are representative of subspecialist national practice in England and Wales. There are approximately 150 Consultant Ophthalmologists in England and Wales with a glaucoma subspecialist interest as estimated from a list obtained from the Royal College of Ophthalmologists. Our surveyed population would therefore represent nearly half of the glaucoma specialists nationally. Further, an assumption has been made that the method of survey delivery (conference or postal) has not influenced responses from participants and that the responses have been combined for reporting.

Responses to question 5 were classified into distinct categories, for ease of interpretation, by only one of the investigators (HB). As the responses were generally non-ambiguous, it is unlikely that subjectivity contributed to the misclassification of responses. The survey used was developed by consensus between scientists in vision research, psychology and ophthalmologists and is not a validated tool for assessing attitudes for VF testing.

In conclusion, the variable attitudes of ophthalmologists with a glaucoma subspecialty to the frequency of VF testing in England and Wales highlight the need for further research in this area to first establish current practice and, second, to provide a firmer evidence base for designated VF test intervals. The longer term goal would be to ensure optimal resource utilisation and a consistent, high standard of practice nationally.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

David Crabb's coinvestigators on the NIHR Health Services and Delivery Research programme of work (project number 10/2000/68) are David Garway-Heath (NIHR Biomedical Research Centre for Ophthalmology, Moorfields Eye Hospital Foundation NHS Trust & UCL Institute of Ophthalmology London), Claire Lemer (North Middlesex University Trust), Carol Bronze (Patient, Moorfields Eye Hospital Foundation NHS Trust) and Rodolfo Hernandez (University of Aberdeen).

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors have made substantive intellectual contributions to this study: RM drafted the manuscript; HB carried out the analysis presented in the results and acquired the data; RAR was involved in the design of the study and acquiring the data; DPC made substantial contributions to conception and design, revising and approving the final article.

Funding: This work was funded by the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR), Health Services and Delivery Research programme (project number 10/2000/68). One of the authors (RM) was supported by the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre based at Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS Foundation Trust and UCL Institute of Ophthalmology. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: City University London School of Health Science Research and Ethics committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Additional data regarding the exact responses given by the specialists to the survey can be obtained on request from the corresponding author (DPC).

References

- 1.Gordon-Bennett PS, Ioannidis AS, Papageorgiou K, et al. A survey of investigations used for the management of glaucoma in hospital service in the United Kingdom. Eye (London) 2008;22:1410–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weinreb RN, Khaw PT. Primary open-angle glaucoma. Lancet 2004;363:1711–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.NICE. ed. CG85 Glaucoma: NICE guideline. In: Published clinical guidelines. 1st edn National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence; London: National Collaborating Centre for Acute Care at The Royal College of Surgeons of England [Google Scholar]

- 4.Society EG. Terminology and guidelines for glaucoma. 3rd edn. Savona, Italy: Editrice Dogma, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chauhan BC, Garway-Heath DF, Goni FJ, et al. Practical recommendations for measuring rates of visual field change in glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol 2008;92:569–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-9476. Crabb DP, Garway-Heath DF. Intervals between visual field tests when monitoring the glaucomatous patient: wait-and-see approach. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2012;53:2770–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tatham A, Murdoch I. The effect of appointment rescheduling on monitoring interval and patient attendance in the glaucoma outpatient clinic. Eye (London) 2012;26:729–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crabb DP. Frequency of visual field testing when monitoring patients newly diagnosed with glaucoma. NIHR Health Services Programme. Version 1 ed: National Institute for Health Research, 2011:Project ref 10/2000/68.

- 9.Nouri-Mahdavi K, Zarei R, Caprioli J. Influence of visual field testing frequency on detection of glaucoma progression with trend analyses. Arch Ophthalmol 2011;129:1521–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gardiner SK, Crabb DP. Frequency of testing for detecting visual field progression. Br J Ophthalmol 2002;86:560–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jansonius NM. Progression detection in glaucoma can be made more efficient by using a variable interval between successive visual field tests. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2007;245:1647–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jansonius NM. Towards an optimal perimetric strategy for progression detection in glaucoma: from fixed-space to adaptive inter-test intervals. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2006;244:390–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharma A, Jofre-Bonet M, Panca M, et al. Hospital-based glaucoma clinics: what are the costs to patients? Eye (Lond) 2010;24:999–1005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhu H, Crabb DP, Fredette MJ, et al. Quantifying discordance between structure and function measurements in the clinical assessment of glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol 2011;129:1167–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Russell RA, Malik R, Chauhan BC, et al. Improved estimates of visual field progression using Bayesian linear regression to integrate structural information in patients with ocular hypertension. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2012;53:2760–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Medeiros FA, Leite MT, Zangwill LM, et al. Combining structural and functional measurements to improve detection of glaucoma progression using Bayesian hierarchical models. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2011;52:5794–803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.