Abstract

Objective

To assess scientific publication and map research gaps on access to medicines (ATM) in Latin American and the Caribbean low-income and middle-income countries (LMIC).

Design

Scoping review. Two independent reviewers assessed studies for inclusion and extracted data from each study.

Information sources

Search strategies were developed and the following databases were searched: MEDLINE, ISI, SCOPUS and Lilacs, from 2000 to 2010.

Eligibility criteria

Research articles and reviews published in English, Spanish and Portuguese were included. Studies including only high-income countries were excluded, as well as those carried out in very limited settings and discussion papers.

Results

The 77 articles retained were categorised through consensus among the research team according to the level of the health system addressed, ATM domain and research issues covered. Publications on ATM have increased over time during the study period (r 0.93, p=0.00; R2 0.85). The top five countries covered were Brazil (68.8%), Mexico (15.6%), Colombia (11.7%), Argentina (10.4%) and Peru (10.4%). ‘Health services delivery’ and ‘patients, household and communities’ were the health system levels most frequently covered. The ATM domains ‘leadership and governance’, ‘sustainable financing, affordability and price of medicines’, ‘medicines selection and use’ and ‘availability of medicines’ were the top four explored. There are research gaps in important areas such as ‘human resources for health’, ‘global policies and human rights’, ‘production of medicines’ and ‘traditional medicine’.

Conclusions

The upward trend on scientific publication reflects a growing research capacity in the region, which is concentrated on research teams in selected countries. The gaps on research capacity could be overcome through research collaboration among countries. It is important to strengthen these collaborations, assuring that interests and needs from the LMIC are addressed and local capacity building is promoted.

Keywords: Access to medicines, Bibliometrics, Scoping study, Low and middle-income countries, Latin America, Caribbean region

Article summary.

Article focus

To identify methodological approaches and research issues which address access to medicines (ATM) in Latin American and the Caribbean (LAC) in the published literature.

To learn about LAC researchers’ capacity to produce evidence on ATM through articles published in peer-reviewed journals.

To identify research gaps on ATM that should be addressed in future studies.

To map potential opportunities for south–south collaboration on ATM research.

Key messages

An increasing trend in scientific publications on ATM reflects a growing research capacity in LAC.

Scientific publications in peer-reviewed journals are concentrated in few countries and focus on well-established areas and themes.

‘Health services delivery’ and ‘patients, household and communities’ were the health system levels most frequently covered.

ATM domains, ‘leadership and governance’, ‘sustainable financing, affordability and price of medicines’, ‘medicines selection and use’ and ‘availability of medicines’ were the top four explored.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Local databases in Spanish and in Portuguese, the main languages in the region, which are generally not covered in other similar studies, were searched.

A quality assessment of the papers retained was performed.

Introduction

Access to medicines (ATM) is a key component of healthcare systems. The provision of regular access to affordable, appropriate and high-quality medicines has been established as a global priority, highlighted in several international commitments such as World Health Assembly's resolutions,1–4 Millennium Development Goals,5 UNGASS declarations,6 7 the Oslo Declaration8 and the Political Declaration on HIV and AIDS: Intensifying Our Efforts to Eliminate HIV and AIDS.9 In line with these commitments, governments of many low-income and middle-income countries (LMIC) have implemented policies aimed at improving ATM.

Scaling-up ATM in LMIC has been a major challenge faced by governments and health authorities. The delivery of medicines to most people in need depends on a series of efforts related to different access components or dimensions such as sustainable financing, the existence of a network of reliable health services and an efficient supply chain management.10

In this context, the existence of reliable and accurate information on the different components of ATM is crucial for better decision-making. Despite the growing number of studies on issues like price and availability,11 quality data on access to and use of medicines are still lacking.12 13

This work is part of activities carried out within the ATM policy research program, recently implemented by the Alliance for Health Policy and System Research.14

This paper aims to assess scientific publication trends on ATM in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) and to map research gaps.

Methods

A scoping study15 16 of the scientific literature on ATM was performed covering 10 years, from January 2000 to September 2010. This review intended to map scientific production on ATM-related topics in LAC focusing on methodological approaches used to study ATM, institutions and countries involved as well as the main issues raised by authors.

Databases searched were MEDLINE, ISI, SCOPUS and Lilacs, covering publications on ATM in the fields of health, social sciences and humanities. Search terms were set and combined according to the database features (table 1).

Table 1.

Search strategy for scientific publication on access to medicines in Latin America and Caribbean syntax by database, 2000–2010

| Database | Search strategy syntax | Note |

|---|---|---|

| MEDLINE | (“pharmaceutical preparations”[MeSH Terms] OR “drugs, essential”[MeSH Terms] OR “drugs, generic”MeSH Terms]) AND (“health services accessibility”[MeSH Terms] OR “health policy”[MeSH Terms]) AND (“humans”[MeSH Terms] AND (English[lang] OR Spanish[lang] OR Portuguese[lang]) AND (“2000/01/01”[PDAT]: “2010/09/30”[PDAT])) AND (“humans”[MeSH Terms] AND (English[lang] OR Spanish[lang] OR Portuguese[lang]) AND (“2000/01/01”[PDAT]: “2010/09/30”[PDAT])) | Thesaurus exists. These terms were identified with the support of an expert on bibliography search strategy |

| Lilacs | Portuguese ((Preparações Farmacêuticas) OR (Medicamentos Essenciais) OR (Medicamentos Genéricos)) AND ((Acesso aos serviços de saúde) OR (Política de Saúde)) em assunto (search for Mesh/Desc terms) Spanish ((Preparaciones Farmacéuticas) OR (Medicamentos Esenciales) OR (Medicamentos Genéricos)) AND ((Accesibilidad de los Servicios de Salud) OR (Política de Salud)) English ((Pharmaceutical Preparations) OR (Drugs, Essential) OR (Drugs, Generic)) AND ((Health Services Accessibility) OR (Health Policy)) |

|

| Scopus | (TITLE-ABS-KEY(“access to medicines” OR “medicines price” OR “rational use of medicine” OR “medicines affordability” OR “affordability of medicines” OR “accessibility of medicines” OR “medicines accessibility” OR “medicines financing” OR “availability of medicines” OR “medicines availability”) AND SUBJAREA(mult OR agri OR bioc OR immu OR neur OR phar OR mult OR medi OR nurs OR vete OR dent OR heal OR mult OR arts OR busi OR deci OR econ OR psyc OR soci) AND PUBYEAR AFT 1999 AND PUBYEAR BEF 2011) | Thesaurus does not exist These terms came from the guiding template proposed by AHPSR, 201218 |

| ISI | Topic=(access to medicines OR “medicines price” OR “rational use of medicines” OR “medicines affordability” OR “affordability of medicines” OR “accessibility of medicines” OR “medicines accessibility” OR “medicines financing” OR “availability of medicines” OR “medicines availability”) Refined by: languages=(ENGLISH OR PORTUGUESE OR SPANISH) AND Publication Years=(2010 OR 2003 OR 2009 OR 2004 OR 2008 OR 2001 OR 2007 OR 2000 OR 2006 OR 2005) |

The articles identified were screened and selected according to inclusion criteria, as follows: focus on ATM; addressing at least one LMIC at national or sub-national levels (districts, provinces, states); written in English, Spanish and Portuguese languages; abstract available; full-text available in open-access journals and on Periódicos CAPES e-journals database. Both empiric and reviews articles were included. For review articles, some additional inclusion criteria applied: the article must include information on how the literature search was done and which scientifically recognised index was used; selection criteria must define the type of articles included in the review. Exclusion criteria were studies including only high-income countries and empirical studies carried out in a very limited setting such as hospitals or health centres. At all steps papers were reviewed and data extracted by two independent reviewers.

An exploratory analysis was performed taking into account the steps described as follows.

Articles retrieved were first sorted out according to the following variables: language; target population (general or disease specific), year of publication; type of study (empiric or review); the first author's country of residence and affiliation and countries covered.

Second, based on Bigdeli et al,17 papers were categorised by level of the health system addressed: (I) patients, households and communities; (II) health services delivery; (III) health sector (policies or institutions); (IV) national policies or institutions cutting across sectors and (V) regional and international policies and institutions.

Third, they were classified according to ATM domains18 as follows: (1) medicines selection and use (consumption, rational use); (2) sustainable financing, affordability and price of medicines; (3) leadership and governance (policies formulation and implementation, legislation, health litigation); (4) availability of medicines; (5) human resources for health; (6) quality of medicines and quality assurance systems and (7) medicines information and information systems.

Fourth, based on articles’ research questions, research issues were identified and categorised by consensus among authors in 19 categories related to each of the above ATM domains (box 1).

Box 1. Categories related to ATM domains.

Categories

Medicines use

Availability

Medicines price!affordability

Financing model of medicines

Health litigation

Policy implementation

Multisource medicines!generics

Legislation and regulation

Good pharmacy practices

IP-related issues

Evidence and health policy

Methods

Socioeconomic determinants

Healthcare and medicines seeking behavior

Provision model of medicines

Human resources for health

Global policies and human rights

Production of medicines

Traditional medicine

Descriptive statistics (frequencies and percentages) were calculated to characterise distribution of papers according to the variables and categories aforementioned above. Linear regression was performed to test the relationship between number of papers and year of publication. The strength and direction of this association was estimated by calculating the correlation coefficient (Pearson's r) and its statistical significance (p value). Data linearity fit was expressed by coefficient of determination (R2). Identified trends were depicted on scatter plots.

It was observed that a great part of papers retrieved covered Brazil and were produced by Brazilian authors. In order to avoid taking Brazilian production trends as the general one, data were stratified by countries covered (Brazil, LAC excluding Brazil and multicountry studies) and the first author's country of residence (Brazil; LAC excluding Brazil; and EU/USA), when analysing time trends.

Results

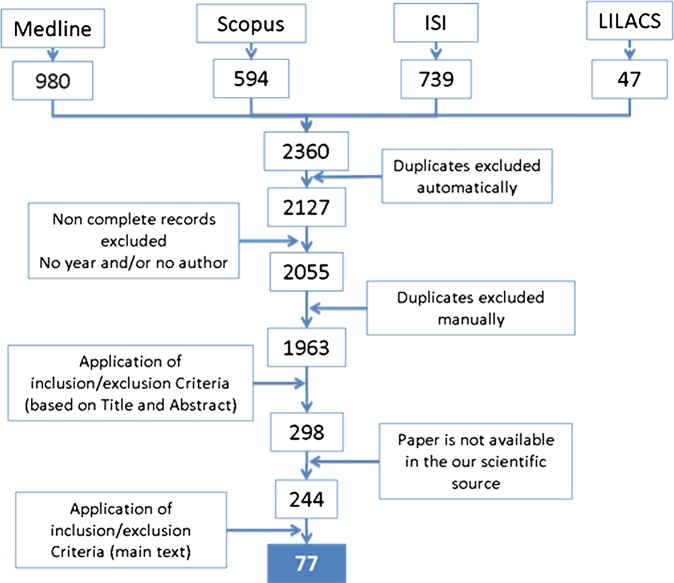

A total of 77 scientific articles were retained after the selection process as depicted in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Stepwise process for selection of papers concerning access to medicines in Latin America and Caribbean, 2000–2010.

Around half of the retained papers (53.7%) were published in English, 37.7% in Portuguese and 9.1% in Spanish. Most of them (72.7%) targeted general population. The majority of studies (85.7%) were empiric—quantitative and qualitative approaches were adopted in 58.4% and 22.1%, respectively; mixed-methods were used in the remaining 19.5%.

Regarding the first author's country of residence, Brazil was the leader (57.1%), followed by the USA (20.8%). The first author's affiliation was linked to academic institutions in 76.6% of the papers.

The top five countries covered were Brazil (68.8%), Mexico (15.6%), Colombia (11.7%), Argentina (10.4%) and Peru (10.4%). This picture changes when multi-country studies are excluded and only studies covering a single country are considered: in such a case, Brazil accounted for 55.8% of publications, while the aforementioned countries accounted for 6.5%, 3.9%, 1.3% and 3.9%, respectively.

The first authors of the 17 multicountry studies (22.1% of 77) were mostly affiliated to institutions from the USA (8) and Brazil (5).

Multicountry studies were mostly published in English (94.1%), especially those covering LAC excluding Brazil. For studies covering Brazil the preferential language was Portuguese (65.1%).

When the first author's country of residence was Brazil, Portuguese was the most frequent language of publication (65.9%). In LAC countries, excluding Brazil, around half of the publications were in Spanish (55.6%) and when the first author's country of residence was in the EU or the USA, English was the language of publication for all papers.

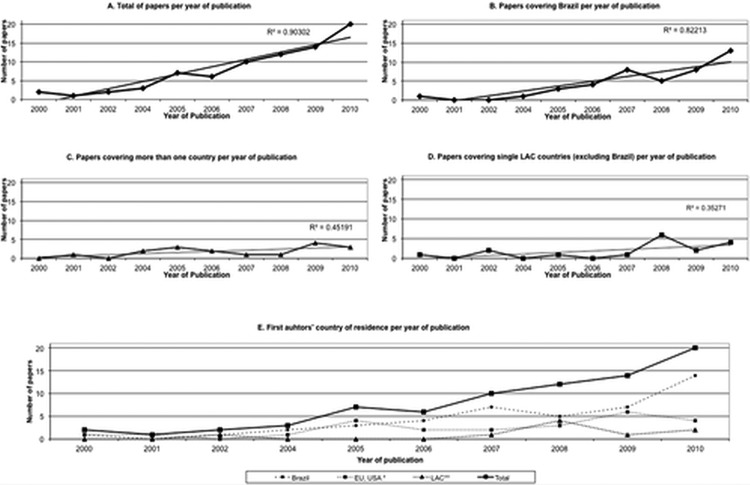

The number of publications related to ATM increased over time during the study period (figure 2A). The overall correlation (r) reflecting the association between the number of publications and year was 0.93 (p=0.00). The R2 value 0.85 indicates a significant sustained increase over the 10 years covered by the study period. This increase refers mostly to publications covering Brazil as study setting (r 0.89, p<0.01, R2 0.79—figure 2B) and less extensively to those covering more than one country (r 0.69, p<0.05, R2 0.48—figure 2C). The slight increase in the number of publications on ATM covering single LAC countries, excluding Brazil, however, shows little statistical significance (r 0.56, p<0.10, R2 0.31—figure 2D). The analysis by country of residence of the first author points out to similar trends, as can be observed in figure 2E: publication with authors from Brazil responded for the higher growth rate (r 0.87, p<0.01, R2 0.76), followed by those from high-income countries (r 0.78, p<0.01, R2 0.61), and other LAC countries (r 0.59, p<0.10, R2 0.34).

Figure 2.

Number of papers related to access to medicines in Latin America and Caribbean per year by country covered and first author's country of residence, 2000–2010.

As table 2 shows, ‘health sector’, ‘health services delivery’ and ‘patients, household and communities’ were the three health system levels most frequently covered. The ATM domains ‘leadership and governance’, ‘sustainable financing, affordability and price of medicines’, ‘medicines selection and use’ and ‘availability of medicines’ were the top four explored.

Table 2.

Distribution of papers by health system level, access to medicine domain and research issue, 2000–2010

| Classification/categories | Frequency (N) | Per cent* |

|---|---|---|

| Health system levels | ||

| Health sector (policies or institutions) | 41 | 35.34 |

| Health services delivery | 30 | 25.86 |

| Patients, households and communities | 28 | 24.14 |

| National policies or institutions cutting across sectors | 11 | 9.48 |

| Regional and international policies and institutions | 6 | 5.17 |

| Domains | ||

| Leadership and governance | 25 | 26.04 |

| Sustainable financing and affordability and price of medicines | 22 | 22.92 |

| Medicines selection and use | 21 | 21.88 |

| Availability of medicines | 16 | 16.67 |

| Human resources for health | 3 | 3.13 |

| Quality of medicines and quality and quality assurance systems | 3 | 3.13 |

| Medicines information and information systems | 2 | 2.08 |

| N/A | 4 | 4.17 |

| Research issue | ||

| Medicines use | 14 | 18.20 |

| Availability | 13 | 16.90 |

| Medicines price/affordability | 11 | 14.30 |

| Financing model of medicines | 10 | 13.00 |

| Health litigation | 9 | 11.70 |

| Policy implementation | 9 | 11.70 |

| Multisource medicines/generics | 8 | 10.40 |

| Legislation and regulation | 5 | 6.50 |

| Good pharmacy practices | 4 | 5.20 |

| IP-related issues | 4 | 5.20 |

| Evidence and health policy | 3 | 3.90 |

| Methods | 3 | 3.90 |

| Socioeconomic determinants | 3 | 3.90 |

| Healthcare and medicines seeking behavior | 2 | 2.60 |

| Provision model of medicines | 2 | 2.60 |

| Human resources for health | 1 | 1.30 |

| Global policies and human rights | 1 | 1.30 |

| Production of medicines | 1 | 1.30 |

| Traditional medicine | 1 | 1.30 |

Categories are not mutually exclusive.

The top most researched issues were ‘medicines use’ (18.2%), ‘availability’ (16.9%), ‘medicines price/affordability’ (14.3%), ‘financing model of medicines’ and ‘health litigation’ (11.7%), ‘policy implementation’ (11.7%) and ‘multisource medicines/generics’ (10.4%).

Discussion

The growing trend in the production of papers related to ATM in LAC countries found in this study is consistent with the findings of other studies.12 13 However Ritz et al13 report a steep increase in the number of papers in 2007, while this study shows a consistent trend of growth in Brazil's production from 2000 to 2010. As previously mentioned, this production accounts for most of the general growth identified in America's LMIC. This is consistent with an important and rapid growth of general scientific production in Brazil which has been observed in the last decade, especially in the field of public health.19

There are at least two main reasons to explain this picture. First, there has been a longstanding investment in capacity building for research in Brazil since mid-1970s. Second, since 2003 Brazilian government, among other initiatives, has been increasing funds and grants for scientific research in priority areas of knowledge, which includes public health.20 21 Moreover, only five countries in the region have official health research priority agendas (Argentina, Brazil, Costa Rica, Paraguay and Peru) and only two of them (Brazil and Paraguay) explicitly include ATM issues.22

The majority of papers published in Portuguese reflect the leadership of Brazil in the scientific production of LAC. This is also a consequence of the increasing public financing for research driven by Ministry of Health priorities. In this case, rather than focus on the dialogue with the international community of researchers, Brazilian authors gave priority to provide health authorities and national researchers with relevant information that can be used to promote improvements of the health system.19

However, it is noteworthy that a trend in the growth of publications in English23 was also observed, especially when multicountry studies were concerned. It reflects the interest of high-income countries’ authors in the implementation of ATM policies in the subregion. This also indicates an effort developed by LAC researchers to contribute to the discussion of internationally relevant issues, which takes place mainly in English language peer-reviewed journals.

The choice for research method should be based on the research question and both qualitative and/or quantitative methods are acceptable. However, as the size of the effect is usually a crucial estimation, quantitative methods, particularly randomised clinical trials, have been preferred for producing evidence, including for social and health policies.24 25 Recently, the importance of qualitative approach has been increasingly recognised and used for health services and public health studies26 This same pattern was observed in our study.

A smaller proportion of studies employing qualitative methods was found, which indicates the need for a better balance between quantitative and qualitative research, to reflect context specificities as well as to enhance policy learning.27 28 The proportion of studies using mixed-methods may demonstrate the complexity of ATM issues, within the broader HPSR field, referred by Gilson et al27 and Sheikh et al28 who demand for interdisciplinary developments and a wide spectrum of methodologies.

Considering the Health System Levels, the most important point of discussion is the scarcity and small variety of issues addressed within levels IV (national policies or institutions cutting across sectors) and V (regional and international policies and institutions). This reflects the lack of attention in research that is given to: (1) national issues beyond the health sector and related to economy or trade, such as medicines production and legislation and regulation and (2) international issues, such as ‘global policies’ and ‘human rights’ and ‘international legislation’. The few publications found in level IV focused on litigation and court decisions while the studies in level V addressed intellectual property issues. These findings point to the importance of approaching ATM in broader national and international contexts.

Research gaps were identified in the domains of ‘human resources for health’, ‘quality of medicines and quality and quality assurance systems’, and ‘medicines information and information systems’. It is noteworthy that two of the most important health system building blocks,12 ‘human resources’ and ‘health information’, are under-represented in ATM research.

The categorisation according to issues clearly shows concentration of publications in some, more traditional areas—‘medicines use’, ‘availability’, ‘medicines price/affordability’ and ‘financing model of medicines’, directly related to the WHO ATM framework.10 Meanwhile, there are research gaps in other important areas as ‘human resources for health’, ‘global policies and human rights’, ‘production of medicines’ and ‘traditional medicine’.

Our study presents several limitations. Independently of the approach, the quality of studies is a critical issue to be considered, in order for the results to appropriately inform decision making.25 29 However, as we aimed at a comprehensive scoping study rather than an in-depth literature review no judgment on quality criteria was applied to papers retrieved and this aspect was not considered in the trends addressed.

Regarding the language criterion, which was used on initial search filters, it should be noted that only two countries in the region have different native languages from those included. This filter was therefore not considered as a significant bias.

Owing to feasibility, open sources and the Brazilian academic public database—Periódicos CAPES—were used to recover full texts. This database is fairly broad (around 20 000 journals) and papers not available there or through other open sources are hardly accessible to researchers or policymakers in the region. Therefore, this was not considered a relevant bias in terms of availability of evidence to guide further research and decision-making. Publications were assumed here as proxies of research production. However, barriers such as the acceptability of local approaches in high-impact scientific journals, difficulties in scientific writing and writing in English30 have a negative impact on the conversion of research findings in scientific communications.

Since ‘access to medicines’ is not an MeSH term and the existing MeSH terms are not suitable, a broad range of terms were used to get the best possible coverage of relevant papers. Moreover, by retaining only the available full text article, the results might be influenced by the ‘full text bias’.

Finally, despite the fact that the study covered a large period of 10 years, the search was limited to late 2010 and does not account for papers published in 2011 and 2012. This is a relative limitation as trends over time are analysed and reveal significant changes over the past decade.

In conclusion, our study identified relevant scientific publication trends on ATM reflecting a growing research capacity in the region, but concentrated in few countries and research themes. This apparent gap on research capacity in many LMIC could be overcome through research collaboration among countries. Thus health research funders should promote this type of arrangement, to enhance and take advantage of the existing capacity, while fostering a more balanced development in the region. Also, a number of publications involving researchers and institutions from high-income countries were identified. It is important to strengthen this collaboration ensuring that interests and needs from the LMIC are addressed and local capacity building is promoted.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Nelly Marin, James Fitzgerald and Analia Porras, officials of the Medicines and Vaccines Cluster/Pan American Health Organization headquarters for their inputs and support essential to make this work feasible, to Professor Maria de Fatima M. Martins for her help on the literature search and Paula Pimenta de Souza for revision of the main study report.

Footnotes

Contributors: ICME contributed to the conception of the paper, outlined the first draft, performed statistical analysis, participated in writing and reviewing the text and approved the submitted version. MAO contributed to the conception of the paper, outlined the first draft, participated in writing and reviewing the text and approved the submitted version. VLL coordinated the general project from where the approach belongs to, participated in the conception of the paper, participated in writing and reviewing the text and approved the submitted version. TBA contributed with statistical analysis, participated in writing and reviewing the text and approved the submitted version. MB contributed in the discussion section, participated in reviewing the text and approved the submitted version.

Funding: Funded by AHPSR/WHO.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The complete database of retrieved papers and all the search history is available with the corresponding author and also with the funder.

References

- 1.WHA, (World Health Assembly) WHA 54.10 Scaling up the response to HIV/AIDS. Geneva: Word Health Organization, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHA, (World Health Assembly) WHA 61.21 Global strategy and plan of action on public health, innovation and intellectual property. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHA, (World Health Assembly) WHA 54.11 WHO medicines strategy. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHA, (World Health Assembly) WHA 55.14 Ensuring accessibility of essential medicines. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 5.UNGA, (United Nations General Assembly) UN 55.2 United Nations millennium declaration. New York: United Nations, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 6.UNGASS, (United Nations General Assembly—Special Session) UNGASS S-26/2 declaration of commitment on HIV/AIDS. New York: United Nations, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 7.UNGASS, (United Nations General Assembly—Special Session) UNGASS 60/262 political declaration on HIV/AIDS. New York: United Nations, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ministers of Foreign Affairs of Brazil, France Indonesia Norway Senegal South Africa and Thailand Oslo ministerial declaration—global health: a pressing foreign policy issue of our time. Lancet 2007;369:1373–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.UNGA, (United Nations General Assembly) UN 65/277 political declaration on HIV and AIDS: intensifying our efforts to eliminate HIV and AIDS. New York: United Nations, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 10.WHO, (World Health Organization) WHO medicines strategy: 2000–2003 framework for action in essential drugs and medicines policy. WHO/EDM/2000.1. Geneva: WHO, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cameron A, Ewen M, Ross-Degnan D, et al. Medicine prices, availability, and affordability in 36 developing and middle-income countries: a secondary analysis. Lancet 2009;373:240–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adam T, Ahmad S, Bigdeli M, et al. Trends in health policy and systems research over the past decade: still too little capacity in low-income countries. PLoS ONE 2011;6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ritz LS, Adam T, Laing R. A bibliometric study of publication patterns in access to medicines research in developing countries. South Med Rev 2010;3:2–6 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.AHPSR, (Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research) Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research. Secondary Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research 2009. http://www.who.int/alliance-hpsr/en/.

- 15.Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol Theory Pract 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci 2010;5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bigdeli M, Jacobs B, Tomson G, et al. Access to medicines from a health system perspective. Health Policy Plan 2012. Published Online First: Epub Date doi:10.1093/heapol/czs108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.AHPSR, (Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research) Access to medicines—priority setting for a health policy and systems research agenda. In: ARPHSP, ed. Access to Medicines Global Stakeholders Meeting; Bangkok, Thailand: ARPHSP, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Victora CG, Barreto ML, Leal MdC, et al. Health conditions and health-policy innovations in Brazil: the way forward. Lancet 2011;2042–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brazil-MoH, (Minister of Health, Brazil) From political to institutional action: research priorities in the ministry of health. Rev Saúde Pública 2006;40:548–52 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guimaraes R, Santos LMP, Angulo-Tuesta A, et al. Defining and implementing a national policy for science, technology, and innovation in health: lessons from the Brazilian experience. Cad Saúde Pública 2006;22:1775–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luiza VL, Emmerick ICM, Azeredo TB, et al. Identification of priority policy research questions on access to medicines in low and middle income countries in Latin America and Caribbean (LAC). Rio de Janeiro: Nucleus for Pharmaceutical Policies/National School of Public Health/Oswaldo Cruz Foundation; 2011:137 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loria A, Arroyo P. Language and country preponderance trends in MEDLINE and its causes. J Med Libr Assoc 2005; 90:381–5 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dixon-Woods M, Bonas S, Booth A, et al. How can systematic reviews incorporate qualitative research? A critical perspective. Qual Res 2006;6:27–44 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Higgins JPT, Green S, eds. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. Oslo: The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chapple A, Rogers A. Explicit guidelines for qualitative research: a step in the right direction, a defence of the ‘soft’ option, or a form of sociological imperialism? Fam Pract 1998:556–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gilson L, Hanson K, Sheikh K, et al. Building the field of health policy and systems research: social science matters. PLoS Med 2011;8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sheikh K, Gilson L, Agyepong IA, et al. Building the field of health policy and systems research: framing the questions. PLoS Med 2011;8:1–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohen DJ, Crabtree BF. Evaluative criteria for qualitative research in health care: controversies and recommendations. Ann Fam Med 2008;6:331–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Victora CG, Moreira CB. Publicações científicas e as relações Norte-Sul: racismo editorial? Rev Saúde Pública 2006;40:36–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.